Article contents

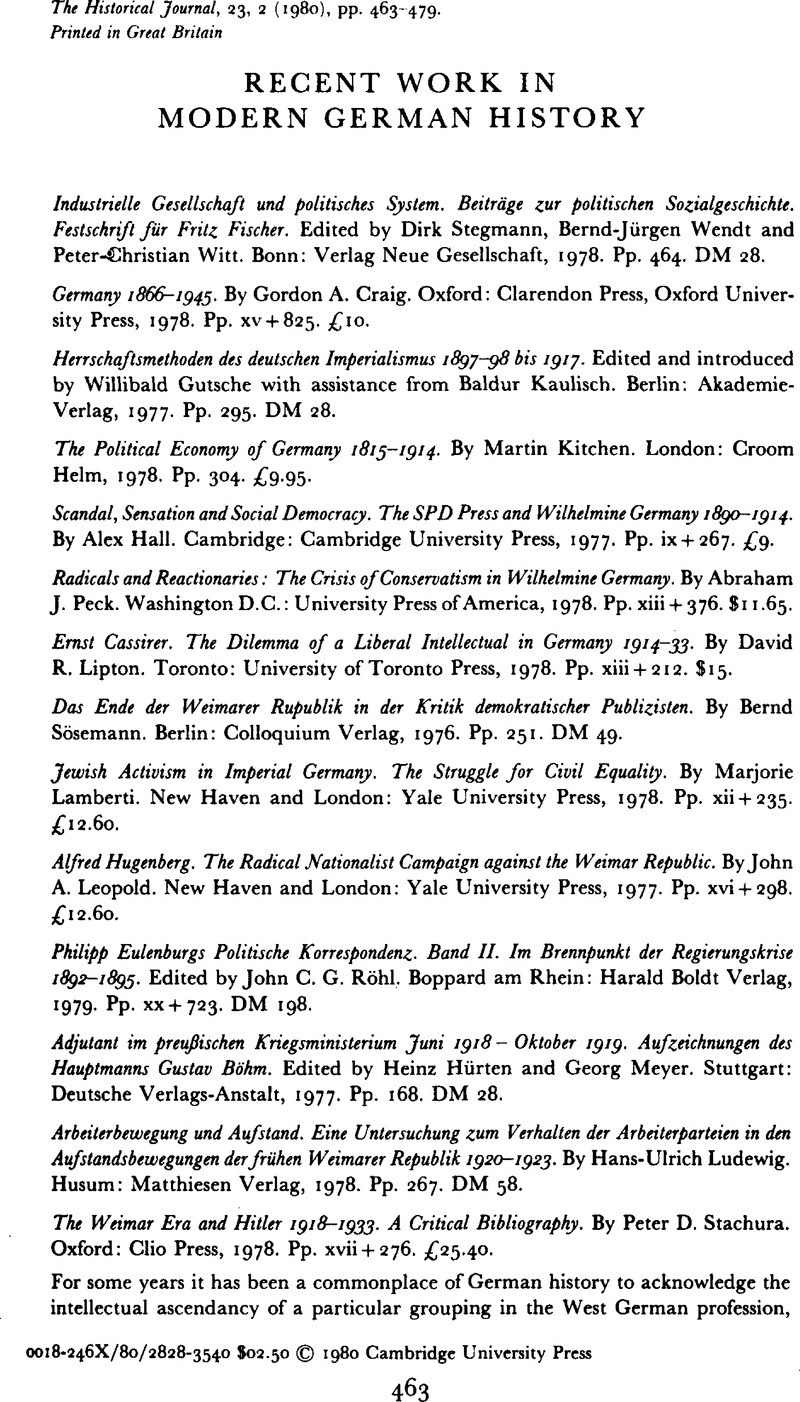

Recent Work in Modern German History

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1980

References

1 In sequence the references are: Sturmer, M. (ed.), Das kaiserliche Deutschland (Düsseldorf, 1970)Google Scholar; Wehler, H.-U. (ed.), Sozialgeschihte Heute (Göttingen, 1974)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Geiss, I. and Wendt, B.-J. (eds.), Deutschland in der Weltpolitik des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts (Düsseldorf, 1973)Google Scholar. Geschichte und Gesellschaft is edited by a larger grouping that includes Wehler, Kocka, Puhle and Winkler, while the Kritische Studien include most major publications by the grouping over recent years. I am not suggesting that innovations in West German historiography have come exclusively from these quarters. Though individually they have worked in many other fields as well, as a grouping these are actually historians of the Wilhelmine political system, and many important initiatives have come from other areas as well (e.g. especially demography and family history). Moreover, by referring to this grouping as a collectivity I am not suggesting that they agree about all things, or that their mutual associations necessarily remain very strong. Clear differences have arisen amongst some individuals, particularly concerning the turn to ‘social’ as opposed to ‘political’ history. All I mean to suggest is that the individuals referred to in the text above have been united by certain common principles in the late-60s, with which they were also publicly identified.

2 Without exception the major studies of Wilhelmine politics have been of this kind, while by comparison the political parties have been systematically neglected. There are now studies of all the major economic pressure groups, and the most important analyses of Imperial politics share the same perspective. The syndrome has started to reappear in work on the 1920s as well.

3 The GDR has an excellent record of publishing accessibile collections of documents which have been long familiar to specialist researchers. See also the 1977 volume of the Jahrbuch für Geschichte (vol. 15), which is devoted to the same theme and period, and can be read as a companion volume of commentaries.

3 This is especially unfortunate for students, as Kitchen gives no indication of the status of the opinions expressed in his book. From this point of view the absence of references or some kind of critical bibliography is inexcusable. It leaves the distinct impression of a book written too easily and too quickly.

5 Unfortunately Hall has been beaten to the post by Klaus Saul and duplicates much of what the latter has published during the last ten years in a series of major articles or in his book, Staat, Industrie, Arbeiterbewegung im Kaiserreich (Düsseldorf, 1974). Otherwise, the section in Hall’s book on the municipalities enters fairly new ground very inadequately, and the one on militarism follows familiar and well-trodden paths.

6 Puhle, H.-J., Agrarische Interessenpolitik und preuβischer Konservatismus im wilhelminischen Reich, 1893–1914 (Hannover, 1966).Google Scholar

7 Briefly Berghahn argued that the conception of Johannes von Miquel, the Prussian finance minister (and despite Berghahn’s claims the real architect of Sammlungspolitik), was far too narrowly based on the party-political Cartel of Conservatives, Free Conservatives and National Liberals, and in particular excluded the Centre party. As a result Tirpitz and Bülow emerged with a new strategy of ‘big’ Sammlung organized around the naval issue and the inclusion of the Centre. The misconceptions behind this view are too many to be discussed here, but it cannot be stressed too strongly that it has no basis in the evidence. Miquel himself explicitly demanded the inclusion of the Centre, the naval issue was kept systematically out of the Sammlung negotiations, Tirpitz took no part in the latter and Bülow very little until 1900, and after assuming the chancellorship Bülow simply took over Miquel’s original conception. See Berghahn, V. R., ‘Das Kaiserreich in der Sackgasse’, Neue Politische Literatur, xvi (1971), 494–506.Google Scholar

8 Fischer, F., Germany’s aims in the First World War (London, 1967)Google Scholar; Stegmann, D., Die Erben Bismarcks (Cologne, 1970)Google Scholar; Fleming, J., Landwirtschqftliche Interessen und Demokratie (Bonn, 1978).Google Scholar

9 In some ways one might argue that Lipton’s book is only secondarily a work of German history, being concerned mainly with the general predicament of liberal intellectuals in the 20th century. Sösemann covers the same ground as Modris Ekstein’s more broadly conceived The limits of reason (Oxford, 1975), which inexcusably he fails to mention.

10 Certain partial exceptions are the following: Sheehan, J. J., German liberalism in the nineteenth century (Chicago, 1978)Google Scholar; White, D. S., The splintered party. National Liberalism in Hessen and the Reich 1867–1918 (Harvard, 1976)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Hunt, J. C., The People’s party in Württemberg and Southern Germany, 1890–1914 (Stuttgart, 1975)Google Scholar. I have tried to formulate the problems in Eley, G., Reshaping the German Right. Radical nationalism and political change after Bismarck (New Haven and London, 1980), chs. 2 and 9.Google Scholar

11 Mommsen, H., Petzina, D. and Weisbrod, B. (eds.), industriells System tout politische Entwicklung in der Weimarer Republik (Düsseldorf, 1974).Google Scholar

12 See for instance: Puhle, H.-J., ’Zur Legende von der “Kehrschen Schule”, Geschichte und Gesellschaft, 4, 1 (1978), pp. 108–19Google Scholar; Berghahn, V. R., ‘Politik und Gesellschaft im Wilhelm-inischen Deutschland’, Neue Politische Literatur, xxiv (1979), 164–95.Google Scholar

13 Eley, G., ‘Capitalism and the Wilhelmine state: industrial growth and political back-wardness in recent German historiography, 1890–1918’, Historical Journal, xxi, 3 (1978), 737–50; Reshaping the German Right, esp. pp. 349–61.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

14 This is the title of an extended review of Craig’s book by Mason, in the Times Higher Education Supplement, 1 Dec. 1978, which brilliantly captures the essence of the mode.

15 The classic text for this tradition was probably Isaiah Berlin’s Historical inevitability (Oxford, 1954) – an essay on which I was still raised as a sixth-former in the mid-1960s.Google Scholar

16 Krieger, L., ‘German history – in the grand manner’, American Historical Review, lxxxiv, 4 (1979), 1011 f.Google Scholar

17 These texts really deserve a full review of their own. John Röhl’s mammoth edition of the Eulenburg correspondence in particular must await final evaluation until the third volume is published.

- 1

- Cited by