No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

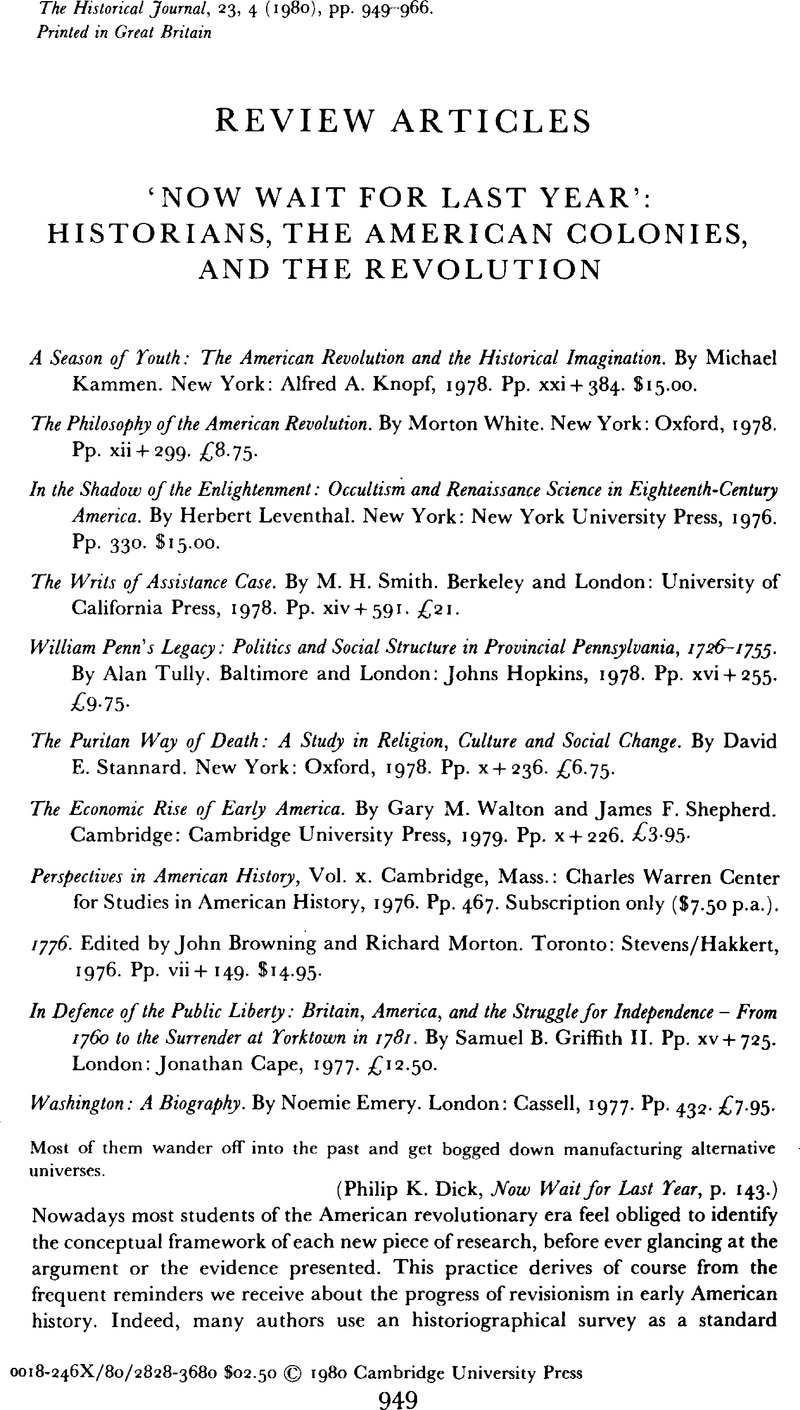

‘Now Wait for Last Year’: Historians, the American Colonies, and the Revolution

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1980

References

1 Morgan, Edmund S. gave the trend impetus with ‘The American Revolution: revisions in need of revising’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. XIV (1957), 3–15CrossRefGoogle Scholar. It was then firmly established by Greene, Jack P., ‘Flight from determinism: a review of recent literature on the coming of the American Revolution’, South Atlantic Quarterly LXI (1962), 235–59Google Scholar; ‘Changing interpretations of early American polities’, in Billington, Ray A. (ed.), The reinterpretation of early American history (San Marino, Calif., 1966)Google Scholar.

2 One of the most valuable contributions of this kind, since it poses a series of major queries in addition to analysing the changes in interpretation, is Wood, Gordon S., ‘Rhetoric and reality in the American Revolution’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. XXIII (1966), 3–32CrossRefGoogle Scholar. No part of this discussion is meant, of course, to minimize the value of a major historiographical analysis dealing with a single aspect: as, for instance, Shalhope, Robert S., ‘Toward a Republican synthesis: the emergence of an understanding of Republicanism in American historiography’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. XXIX (1972), 49–80CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

3 An early example of this type of ‘presentist’ analysis is Smith, Page, ‘David Ramsay and the causes of the American Revolution’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. XVII (1960), 50–77Google Scholar.

4 Higham, John, ‘Beyond consensus: the historian as moral critic’, American Historical Review, LXVII (1962) 609–25CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

5 Hutson, James H., ‘An investigation of the inarticulate: Philadelphia's White Oaks’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. XXVIII (1971), 3–25CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Jesse Lemisch and John K. Alexander, ‘The White Oaks, Jack Tar and the concept of the “inarticulate”’; Simeon J. Crowther, ‘A note on the economic position of Philadelphia's White Oaks’; with a rebuttal by Hutson, James H., William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. XXIX (1972), 109–42Google Scholar.

6 An obvious enough point, made again, in this context, by Barton J. Bernstein when introducing a collection of New Left essays (to which Jesse Lemisch contributed). Bernstein, Barton J. (ed.), Towards a new past: dissenting essays in American history (New York, 1968), p. ixGoogle Scholar.

7 Kammen, Michael, ‘The American Revolution in national tradition’, in Brown, Richard Maxwell and Fehrenbacher, Don E. (eds.), Tradition, conflict and modernization: perspectives on the American Revolution (New York, 1977)Google Scholar.

8 The most effective expression of this view is found in Hartz, Louis, The liberal tradition in America: an interpretation of American political thought since the Revolution (New York, 1955)Google Scholar.

9 Appleby, Joyce, ‘The social origins of American Revolutionary ideology’, Journal of American History, XIX 4 (1978), 937Google Scholar.

10 May, Henry F., The Enlightenment in America (London, 1976)Google Scholar.

11 As far as the Declaration is concerned, White should be read in conjunction with the new and provocative study by Wills, Garry, Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence (Garden City, N.Y., 1978)Google Scholar.

12 Morgan, Edmund S. and Morgan, Helen M., The Stamp Act crisis: prologue to Revolution (Chapel Hill, S.C. 1953)Google Scholar.

13 For résumés of the neo-whig argument see Greene, Jack, ‘Flight from determinism’, pp. 237–41 and 256–7Google Scholar; and Wood, Gordon S., ‘Rhetoric and reality in the American Revolutiuon’, pp. 10–14Google Scholar.

14 Wood, , ‘Rhetoric and reality in the American Revolution’, p. 16Google Scholar.

15 Bailyn, Bernard, The ideological origins of the American Revolution (New York, 1967)Google Scholar.

16 Reid, John Phillip, In a defiant stance: the conditions of law in Massachusetts Bay, the Irish comparison and the coming of the American Revolution (University Park, Penn. and London, 1977)Google Scholar; In a rebellious spirit: the argument of facts, the Liberty riot, and the coming of the American Revolution (University Park, Penn. and London, 1978)Google Scholar.

17 In a rebellious spirit, p. 1.

18 Cook, Edward M. Jr, The fathers of the towns: leadership and community structure in eighteenth-century New England (London, 1976)Google Scholar.

19 Miller, Perry, The New England mind: the seventeenth century (Cambridge, Mass. 1954), pp. 37–8Google Scholar.

20 Bailyn, Bernard, The origins of American politics (New York, 1967)Google Scholar.

21 Shepherd, James F. and Walton, Gary M., Shipping, maritime trade and the economic development of colonial North America (Cambridge, 1972)Google Scholar; Shepherd, James F. and Williamson, Samuel H., ‘The coastal trade of the British North American colonies, 1768–1772’, Journal of Economic History, XXXII 4 (1972), 783–810CrossRefGoogle Scholar; James F. Shepherd and Gary M. Walton, ‘Trade distribution and economic growth in colonial America’, ibid., XXXII, 1 (1972), 128–45.

22 Egnal, Marc and Ernst, Joseph A., ‘An economic interpretation of the American Revolution’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. XXIX (1972), 3–32CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

23 Lax and Pencak refer specifically to: Maier, Pauline, From resistance to revolution: colonial radicals and the development of American opposition to Britain, 1765–1776 (New York, 1972)Google Scholar; Lemisch, Jesse, ‘Jack Tar in the streets: merchant seamen in the politics of revolutionary America’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XXV (1968), 371–407CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and the then unpublished Ph.D. thesis of Hoerder, Dirk, ‘Mobs and people: crowd action in Massachusetts during the American Revolution’ (Free University of Berlin, 1971)Google Scholar. Hoerder, has since published his view of the Boston mob as an uninstitutionalized political force used as a traditional weapon by the whig leadership: Crowd action in revolutionary Massachusetts, 1765–1780 (New York, 1977)Google Scholar.

24 Jensen, Merrill, Founding of a nation (New York, 1968)Google Scholar. See also Weir, Robert M., ‘Who should rule at home: the American Revolution as a crisis of legitimacy for the colonial elite’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, VI (1976), 679–700CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

25 Palmer, R. R., Age of the democratic Revolution (Princeton, N.J., 1959), 1Google Scholar. Christie, Ian R. and Labaree, Benjamin W., Empire or independence: a British-American dialogue and the coming of the American Revolution (Oxford, 1976)Google Scholar.

26 Shy, John, ‘The American Revolution: the military conflict considered as a revolutionary war’ in: Kurtz, Stephen G. and Hutson, James H. (eds.), Essays on the American Revolution (New York, 1973)Google Scholar.

27 Barrow, Thomas C., ‘The American Revolution as a colonial war of independence’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XXV (1968), 452–64CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

28 Higgenbotham, Don, The war of American independence (New York, 1971)Google Scholar; Mackesy, Piers, The war for America, 1775–1783 (London, 1964)Google Scholar.

29 Glorification of Washington's role and personality is not confined to American popular history. A school history text widely used in Britain in the inter-war years eulogized Washington also. A British critic reacted by remarking: ‘This is a nice example of consolation in defeat: not only were we defeated by chaps who were really English but also by an extraordinarily decent chap as American commander.’ Quoted in Billington, Ray Allen (ed.), The historian's contribution to Anglo-American misunderstanding: report of a committee on national bias in Anglo-American history textbooks (London, 1966), p. 64Google Scholar.

30 Kammen cites Wood, Gordon S., ‘The democratization of mind in the American Revolution’, in Leadership in the American Revolution: papers at the third symposium (Library of Congress: Washington, D.C., 1974)Google Scholar; Foner, Eric, Tom Paine and revolutionary America (New York, 1976)Google Scholar; and Young, Alfred E. (ed.), The American Revolution: explorations in the history of American radicalism (DeKalb, Ill., 1976)Google Scholar. Two of the articles in this collection are of particular significance: Joseph Ernst, ‘“Ideology” and an economic interpretation of the Revolution’; Gary B. Nash, ‘Social change and the growth of pre-revolutionary urban radicalism’.

31 For example explicit reference to ‘modernisation’ is made by Edward Countryman in ‘“Out of the bounds of the law”: northern land rights in the eighteenth century’, in Alfred A. Young (ed.), The American Revolution.

32 The epithets are selected, from a number of definitions, almost at random. Other antitheses frequently mentioned in the context are apolitical–politically activist, homogeneity–differentiation, role-acceptance–choice-making, fatalist–optimist, and so on.

33 Those wishing to attempt the heady business of tracing the progress of modernization theory may find it convenient to begin with Inkeles, Alex and Smith, David H., Becoming modern: individual change in six developing countries (Cambridge, Mass. 1974)CrossRefGoogle Scholar and Apter, David E., Some conceptual approaches to the study of modernization (Englewood Cliffs, N.J. 1968)Google Scholar. The literature applying the concept to European history is now too vast for summary here; casual search of the contributions in the last decade to the Journal of Interdisciplinary History and the Journal of Social History will indicate the flavour of the work mentioned above. Three articles show the extension of the concept: Apter, David E., ‘Radicalization and embourgeoisement: some hypotheses for a comparative study of history’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, I (1971), 265–305CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Wrigley, E. A., ‘The process of modernization and the industrial revolution in England’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, III (1973), 225–59Google Scholar; Sewell, William H., Social change and the rise of working class politics in nineteenth century Marseilles’, Past and Present, LXV (1974). 75–110CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

34 Tilly, Charles, The modernization of political conflict in France’, in Harvey, Edward B. (ed.), Perspectives on modernization: essays in memory of Ian Weinberg (Toronto, 1972)Google Scholar; Charles, Louise and Tilly, Richard, The rebellious century, 1830–1930 (Cambridge, Mass. 1975)Google Scholar. I am grateful to Dr David Nicholls for his guidance on Tilly's work on France.

35 Tilly, , ‘Collective action in England and America, 1765–1775’, in Brown, and Fehrenbacher, (eds.), Tradition, conflict and modernization, pp. 71–2Google Scholar.

36 Ibid. p. 72.

37 Ibid. p. 72.

38 Wood, Gordon S., ‘Rhetoric and reality in the American Revolution’, p. 26Google Scholar.

39 Lockridge, Kenneth A., ‘Social change and the meaning of the American Revolution’, Journal of Social History, VI (1972), 397–439Google Scholar.

40 Brown, Richard D., ‘Modernization and the modern personality in early America’, Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies II (1971–1972), 201–28Google Scholar.

41 Bushman, Richard L., Puritan to Yankee: character and the social order in Connecticut, 1695–1765 (Cambridge, Mass. 1967)Google Scholar; Rowland Berthoff and John Murrin, ‘Feudalism, communalism and the yeoman freeholder: the American Revolution as a social accident’, in Kurtz and Hutson, Essays on the American Revolution.

42 Lockridge, , ‘Social change and the meaning of the American Revolution’, p. 404Google Scholar.

43 Greene, Jack P., ‘The social origins of the American Revolution: an evaluation and an interpretation’, Political Science Quarterly, LXXXVIII (1973), 1–22CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

44 Jones, Gareth Stedman, ‘From historical sociology to theoretical history’, British Journal of Sociology XXVII (1976), 295–305CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

45 Kenneth A. Lockridge, ‘The American Revolution, modernization and man: a critique’, in Brown and Fehrenbacher, Tradition, conflict and modernization. Lockridge centres this critique on the work of Tilly, whom he shows to have no belief in the notion of a personality transformation either.

46 Lockridge has called modernization the whig metaphor in scientific disguise: ‘The American Revolution, modernization and man’, p. 119.

47 Judt, Tony, ‘A clown in regal purple: social history and the historians’, History Workshop (1979), issue 7, pp. 66–94Google Scholar; quotations here from pp. 77 and 82. The critique of modernization theory above is much in line with the views of Lockridge and Judt, save that Lockridge, while acknowledging many of the defects, still finds it of value as a general interpretative concept.