1. Introduction

Due to the widespread context of rising healthcare costs and the escalating demand for health services, health authorities across the world face the challenging task of deciding which new medical technologies are and are not incorporated into their funded healthcare packages. In recent years, an increasing number of governments have relied on cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) to make informed decisions about pricing and public reimbursement for medical innovations (Paris and Belloni, Reference Paris and Belloni2013; Panteli et al., Reference Panteli, Arickx, Cleemput, Dedet, Eckhardt, Fogarty, Gerkens, Henschke, Hislop, Jommi, Kaitelidou, Kawalec, Keskimaki, Kroneman, Lopez Bastida, Pita Barros, Ramsberg, Schneider, Spillane, Vogler, Vuorenkoski, Wallach Kildemoes, Wouters and Busse2016; Wenzl and Chapman, Reference Wenzl and Chapman2019; Zozaya et al., Reference Zozaya, Villaseca, Abdalla, Fernández and Hidalgo-Vega2022; Russo et al., Reference Russo, Zanuzzi, Carletto, Sammarco, Romano and Manca2023). The ultimate goal of CEAs is to enhance allocative efficiency in the use of healthcare resources by aiming to maximise overall health gains in a population given available funds. There are a number of challenges in introducing the efficiency dimension into decision-making, which have been shared by several countries (Hoffmann and Graf von der Schulenburg, Reference Hoffmann and Graf von der Schulenburg2000). However, while some countries have made substantial progress in incorporating cost-effectiveness evidence into their evaluation processes, others still lag behind.

In Spain, the inclusion of the efficiency dimension in the evaluation of medicines is a recent development, prompting the need to explore why Spain has been a late adopter. In the 1990s, when Australia and Canada pioneered the application of economic evaluation (EE) to health technologies for pricing and reimbursement decisions, Spain had promising assets to follow their lead. Notably, there were competent researchers, including Professor Rovira,Footnote 1 a pioneering figure in Health Economics and EE in Spain, who in the early 1990s, in collaboration with Fernando Antoñanzas, developed a guide on EE commissioned by the Spanish Ministry of Health (Antoñanzas and Rovira, Reference Antoñanzas and Rovira1993; Rovira & Antoñanzas, Reference Rovira and Antoñanzas1995). Another favourable aspect was the existence and subsequent creation of several health technology assessment (HTA) agencies at both central and regional levels, although with limited means and organisational structure (e.g., at the central level, the HTA agency of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and, at the regional level, the agencies that conform the Spanish Network of HTA agencies (RedETS,Footnote 2 Spanish acronym)).

In the years following this promising start, the evaluation of medicines and the evaluation of other health technologies in Spain followed different paths. Non-drug health technologies followed a well-regulated process with clear regulations and organisational development under RedETS (Lobo et al., Reference Lobo, Oliva and Vida2022). RedETS carries out valuable work to inform decisions about the funding (or not) of non-drugs technologies, and is increasingly incorporating the cost-effectiveness criterion into their evaluations (Giménez et al., Reference Giménez, García-Pérez, Márquez, Gutiérrez, Bayón and Espallargues2020). However, the evaluation process for medicines took a different route, lacking comparable regulatory clarity and organisational development. In fact, despite general Spanish regulations emphasising efficiency as a key principle in allocating public resources, specific guidelines for drug evaluation were not developed. In 2011 an amendment to the Medicines Law voted by the Parliament specifically included cost-effectiveness as one of the criteria for reimbursement. However, even then, not the appropriate detailed regulations, nor the required organisational development and resources were provided to enable incorporating the efficiency dimension into the evaluation of drugs (Oliva-Moreno et al., Reference Oliva-Moreno, Puig-Junoy, Trapero-Bertran, Epstein, Pinyol and Sacristán2020).Footnote 3

The late adoption of EE in Spain can be attributed to powerful barriers that will be explored in-depth in Section 4. However, in recent years there have been several actions that have, to some extent, changed the situation in Spain. Firstly, in 2019, the Advisory committee for the financing of pharmaceutical provision (CAPF, Spanish acronym) in the Spanish National Health System (NHS) was created. CAPF is a scientific-technical body, attached to the Ministry of Health that offers guidance to improve the sustainability and efficiency of pharmaceutical provision in the NHS. Among its purposes, CAPF provides advice and recommendations regarding the EE evidence required to support reimbursement and price-setting decisions from the Inter-ministerial commission on drug prices (CIPM). Secondly, the CIPM itself has improved the transparency of its processes by publishing the minutes of its decisions.Footnote 4 In cases where CIMP recommends not financing a medicine under evaluation, it indicates the broad criteria, as outlined in the law that have led to its decision. And thirdly and most notably, in 2020, the Ministry of Health (MoH) approved the Plan for the consolidation of the therapeutic positioning reports (IPTs, Spanish acronym) (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2020a), explicitly identifying the need to incorporate EEs into these reports.

IPTs are exercises of comparative or joint evaluations of medicines, based on scientific evidence, which serve as reference tools for the CIPM and the Directorate general of pharmacy and health products (DGFyPS) in making pricing and reimbursement decisions in Spain. They were created in 2013, but they did not initially incorporate the evaluation of efficiency. To understand the significance of these reports in drug financing and pricing decisions, it is important to note that marketing authorisations granted by the drug regulatory agencies, such as the FDA or EMA, are based on pharmacological and clinical evaluations. These evaluations establish the non-comparative risk/benefit profile of a drug, considering its efficacy and safety. However, in order to determine the added therapeutic and social value of a medicine, a comparative assessment is needed. This assessment aims to ascertain the relative value of the medicine compared to alternative treatments. However, up until 2020, IPTs solely allow determining the therapeutic utility of a medicine (which included the assessment of efficacy, safety, and tolerability), but did not take into account broader impacts. To measure the broader social value of a drug compared to existing alternatives, the assessment ought to incorporate the evaluation of the incremental costs associated with new drugs to arrive at their incremental cost-effectiveness (Puig-Junoy and Peiró, Reference Puig-Junoy and Peiro2009). The 2020 Action Plan marked a milestone for Spanish health authorities as it explicitly states that an ‘Economic evaluation (cost-utility, cost-effectiveness or cost minimisation analysis, according to available evidence) will be included in the IPT’. This is the first time such a clear statement has been made, emphasising the importance of EE as a key element in the drug evaluation process. The Plan included the creation of a new network in charge of the evaluations of medicines named REvalMed (acronym for Red de Evaluación de Medicamentos/Medicines Evaluation Network).

In 2021, the incorporation of EEs into the drug assessment conducted in the IPTs started by a means of a pilot. However, this initiative of incorporating EEs into the drug assessment faced a setback in 2023 when the Spanish courts, following an appeal from Farmaindustria (the Spanish association for the pharmaceutical industry) override the 2020 Plan on formal grounds (Audiencia Nacional, 2023). The reasons and implications of this annulment will be examined in Section 4, alongside with the potential that the recent European Regulation on HTA provides for the development of new and comprehensive regulations for HTA in Spain, now in progress.

In summary, it took nearly a decade to formalise the inclusion of EEs in IPTs in Spain, which was then suspended two years later due to legal concerns. In between, the 2020 Plan initiated a pilot incorporating for the first time EEs into the drug assessment. The aim of this study is twofold: (i) to analyse the uptake of EE analyses in IPTs during this pilot phase comprising the period from the publication of the first IPT incorporating an EE until the Court ruling overturned the Plan (i.e., from June 2021 until July 2023) and (ii) to review the methods and techniques employed in the evaluations conducted during this period.

2. Methods and data

We conducted a review of all IPTs published between the dates of the publication of the first and the last IPT incorporating an EE section (i.e., from the 25 June 2021 until the 5 July 2023). The review relied on information from the Coordination Group of REvalMed meetings and the website of the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products (AEMPS). The minutes of the REvalMed meetings were used to identify the medicines that were agreed to be included in the pilot of the new Action Plan, which required the incorporation of an EE in the assessment presented in the IPT. During this pilot only a fraction of IPTs incorporate such evaluations, first piloting the incorporation of EE in one IPT in each of the 13 clinical categories. Therefore, decisions on which drug assessments included an EE were not based on a specific selection criterion, or if they were, the criteria have not been specified. In addition to the REvalMed minutes, all published IPTs during the evaluation period were manually reviewed to identify any potential additional IPTs incorporating an EE. Thus, the inclusion criteria for this review, and the first step of the study, was to identify the IPTs incorporating an ‘Economic Evaluation’ section. We then analysed in further detail the EEs conducted de novo by the IPT pharmacoeconomic evaluation team, which, according to the 2020 Action Plan, consisted of members of the DGFyPS evaluation team who could be supported by individuals assigned by the Autonomous Communities.

We developed a data extraction sheet to collect the main characteristics of identified EEs. To compare the methods and techniques applied across the EEs conducted, we collected information on a series of items that are in line with internationally recommendations (Husereau et al., Reference Husereau, Drummond, Augustovski, de Bekker-Grob, Briggs, Carswell, Caulley, Chaiyakunapruk, Greenberg, Loder, Mauskopf, Mullins, Petrou, Pwu and Staniszewska2022) and with Spanish guidelines on conducting EEs (López-Bastida et al., Reference López-Bastida, Oliva, Antoñanzas, García-Altés, Gisbert, Mar and Puig-Junoy2010; Puig-Junoy et al., Reference Puig-Junoy, Oliva-Moreno, Trapero-Bertrán, Abellán-Perpiñán and Brosa-Riestra2014; Ortega-Eslava et al., Reference Ortega Eslava, Marín Gil, Fraga Fuentes, López-Briz and Puigventós Latorre2016). These variables were: date of publication; therapeutic (ATC) group; study population; primary clinical outcomes; inclusion of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) measures; inclusion of a review of previous EEs; inclusion of a de novo EE; if not, reason for non-inclusion; type of EE; comparator chosen; perspective; time horizon; discount rate; types of costs included; modelling (yes/no) and, if yes, type; handling of uncertainty; reference to a cost-effectiveness threshold (CET) (yes/no); threshold referred to; main result of the EE in terms of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER); inclusion of budget impact analysis (BIA)Footnote 5; and final funding decision on the evaluated drug. The latter information was extracted from the BIFIMED website,Footnote 6 which provides information on the funding situation of all drugs in Spain. The review of the selected IPTs and data extraction was performed by two of the authors (JO & LVT) in a double-round process. If the two reviewers did not fully agree on any aspect of the data extraction or interpretation of the results, each discrepancy was dealt with by the three authors of the paper.

3. Results

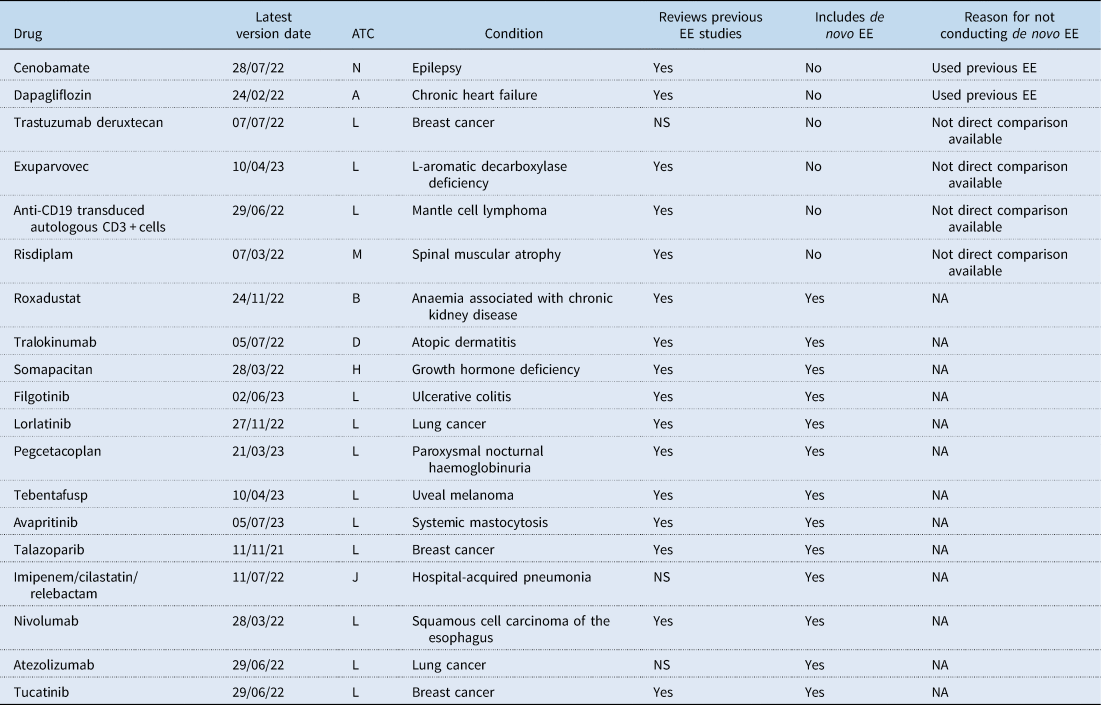

The first IPT incorporating an EE was first published on 25 June 2021.Footnote 7 From that date until 5 July 2023, 181 IPTs were published, with 19 incorporating an EE section (see list in Appendix 1). This implies that over this period, 10.5% of published IPTs were developed under the new Action Plan. Overall, the vast majority of IPTs (60%) are on medicines belonging to the ATC group L, i.e., mostly cancer drugs (see Table 1).

Table 1. Number of IPTs by ATC group during study period

ATC, anatomical therapeutic chemical; EE, economic evaluation, IPT, therapeutic positioning report.

Table 2 summarises the main characteristics of the 19 IPTs that included an EE section. Additional study characteristics are presented in Appendix 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of IPTs incorporating an EE section

NA, not applicable; NS, not stated; EE, economic evaluation, ATC, anatomical therapeutic chemical.

The majority of these 19 IPTs (63%) were also associated with the ATC Group L, which aligns with the overall proportion of IPTs conducted in this therapeutic area. Sixteen IPTs stated that a review of previous EEs was conducted or explicitly mentioned that no previous EEs were identified. Out of the 19 IPTs that included the EE section, six did not carry out a de novo EE. Two of these IPTs argued that previous EEs were already published or provided by the pharmaceutical company or conducted by institutions such as NICE in the UK, CADTH in Canada, or TLV in Sweden. In both of these cases the CEAs available included analyses for the Spanish context. The other four IPTs claimed that due to the lack of direct comparison evidence and the challenges of conducting indirect comparisons it was impractical to undertake an EE.

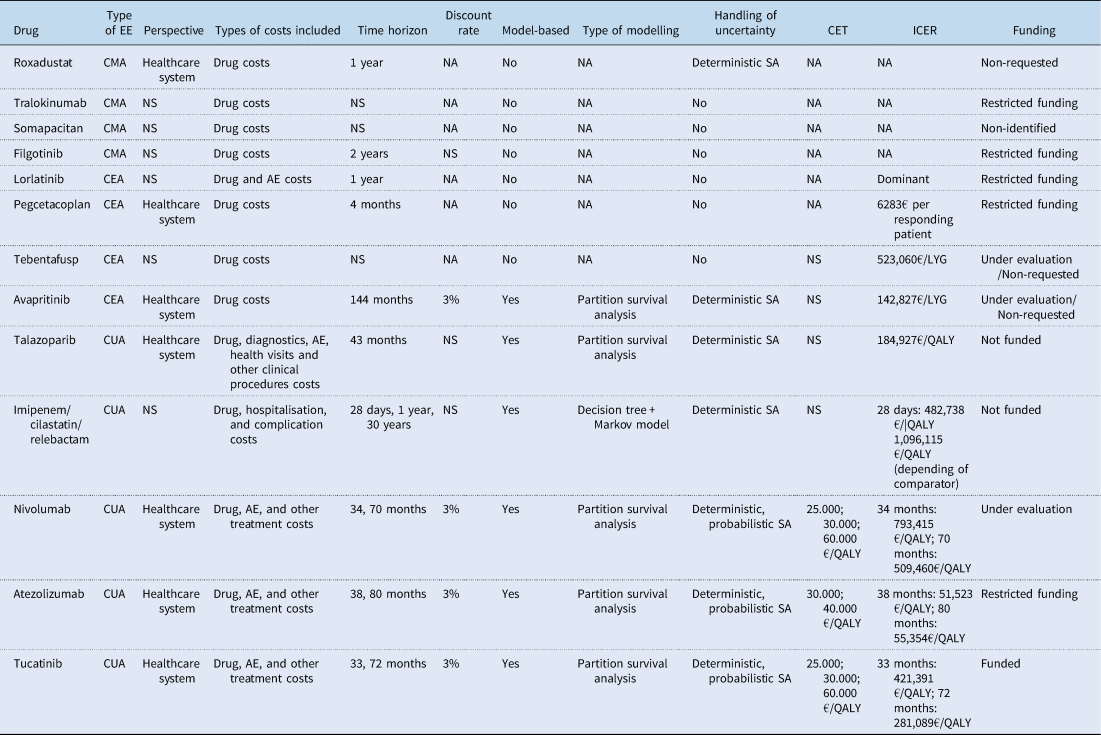

The main characteristics of the 13 IPTs that conducted a de novo EE are summarised in Table 3. Among these IPTs, four limited their analyses to a drug cost-minimisation analysis (CMA), which was justified in two cases by assuming clinical equivalence between the alternatives. Four additional IPTs opted for a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), using measures such as overall survival, progression-free survival, life years gained, and/or the percentage of patients responding to treatment as effectiveness measures. The remaining five IPTs conducted a cost–utility analysis (CUA) using quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) as the outcome measure. Half of the studies clearly stated that they adopted a healthcare system perspective, while the perspective was not specified in six of them. Furthermore, several studies only considered drug costs in their analyses, even when claiming a healthcare system perspective. Among the studies with a time horizon longer than a year, only four IPTs reported the discount rate used, which was consistently 3% for both costs and outcomes. Modelling was performed in six IPTs, with partition survival analyses being the most commonly chosen method. Uncertainty was handled by conducting deterministic sensitivity analyses (SA) in seven studies, of which three also conducted probabilistic SA. Only three IPTs made a reference to the threshold values used to determine cost-effectiveness, with two IPTs considering figures of 25,000, 30,000, and 60,000€/QALY, and one using 30,000 and 40,000€/QALY in their sensitivity analyses. The remaining two IPTs that conducted a CUA simply concluded that the estimated cost per QALY was either above any ‘acceptable threshold in neighbouring countries’ or that the medicine was not an ‘economically competitive alternative’. The ICER values reported in the studies are presented in Table 3. Among the CUAs, ICER exceeded 100,000€/QALY in all but one IPT. Every IPT identified in this review also conducted a budget impact analysis. Finally, the last column of Table 3 indicates whether the drug is currently funded under the Spanish NHS. It is observed that there is no clear relationship between the results of the EE and the funding decision, as several drugs with unfavourable CEA results have been funded. This result complements the findings of Nieto-Gómez et al., Reference Nieto-Gómez, Castaño-Amores, Rodríguez-Delgado and Álvarez-Sánchez2024, who point out that the key variable for the financing of oncological medicines in Spain was their clinical added value.

Table 3. Characteristics of IPTs conducting a de novo EE

EE, economic evaluation; CMA, cost minimisation analysis; CEA, cost-effectiveness analysis; CUA, cost utility analysis; CET, cost-effectiveness threshold; NS, not stated; NA, not applicable; AE, adverse event; SA, sensitivity analysis; LYG, life year gained; QALY, quality-adjusted life year.

4. Discussion

Despite variations in the pace of adoption and implementation processes, the EE of health technologies has gained widespread acceptance as a valuable tool for decision-making regarding the reimbursement and pricing of new medicines (Paris & Belloni, Reference Paris and Belloni2013; Panteli et al., Reference Panteli, Arickx, Cleemput, Dedet, Eckhardt, Fogarty, Gerkens, Henschke, Hislop, Jommi, Kaitelidou, Kawalec, Keskimaki, Kroneman, Lopez Bastida, Pita Barros, Ramsberg, Schneider, Spillane, Vogler, Vuorenkoski, Wallach Kildemoes, Wouters and Busse2016; Wenzl & Chapman, Reference Wenzl and Chapman2019; Russo et al., Reference Russo, Zanuzzi, Carletto, Sammarco, Romano and Manca2023). Spain has been a particular case in this regard. Although it is the fifth largest market in Europe in terms of sales volume of medicines (and among the top 10 in the world), it has only recently begun to incorporate these tools into its drug evaluation processes at the national level (Epstein & Espín, Reference Epstein and Espín2020; Oliva-Moreno et al., Reference Oliva-Moreno, Puig-Junoy, Trapero-Bertran, Epstein, Pinyol and Sacristán2020).

Several studies have analysed the role of EE evidence in Spain (Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, del Llano, Antoñanzas, Juárez, Rovira and Figueras2000, Reference Oliva, del Llano, Antoñanzas, Juárez, Rovira, Figueras and Gervás2001) and in different countries (Hoffmann and Graf von der Schulenburg, Reference Hoffmann and Graf von der Schulenburg2000; George et al., Reference George, Harris and Mitchell2001; Dent and Sadler, Reference Dent and Sadler2002; Sheldon et al., Reference Sheldon, Cullum, Dawson, Lankshear, Lowson, Watt, Wes, Wright and Wright2004; Anell and Persson, Reference Anell and Persson2005; Culyer, Reference Culyer2006; Hanney et al., Reference Hanney, Buxton, Green, Coulson and Raftery2007; Dalziel et al., Reference Dalziel, Segal and Mortimer2008; Schlander, Reference Schlander2008; Menon and Stafinski, Reference Menon and Stafinski2009; O'Donnell et al., Reference O'Donnell, Pham, Pashos, Miller and Smithm2009; Fischer, Reference Fischer2012). The barriers that have hindered the uptake of EE have also been identified in previous work. Merlo et al. (Reference Merlo, Page, Ratcliffe, Halton and Graves2015) points to the limited accessibility and acceptability of cost-effectiveness studies. According to the authors, EEs are often inaccessible to policy-makers due to the lack of relevant studies, the time and cost required to perform them, and the scarce expertise to evaluate quality and interpret results. In addition, analyses may often be viewed as unacceptable because of poor quality of supporting research, assumptions used in modelling, conflicts of interest, difficulties in transferring resources between sectors, negative attitudes towards healthcare rationing, and the absence of equity considerations (Merlo et al., Reference Merlo, Page, Ratcliffe, Halton and Graves2015). In Spain, specific administrative, methodological and practical implementation barriers have been identified. Among these, the controversial nature of decisions on the rationing of scarce resources, the reluctance of politicians to lose their total control of decisions, the absence of models from other sectors, the weight of a history and ‘culture’ of extraordinarily generous pharmaceutical provision, and the weaknesses of the legal, organisational and human resources frameworks have been cited (Lobo et al., Reference Lobo, Oliva and Vida2022; Vida et al., Reference Vida, Oliva and Lobo2023). In the face of these barriers, it was not until 2021 that there was enough political determination to start incorporating EEs in the assessment of drugs. However, as shown in this study, this incorporation during the two-year pilot was limited and then interrupted, at least temporarily, by a court ruling in 2023.

This judgment issued by the Spanish Courts annulled the ‘Plan for the consolidation of the therapeutic positioning reports of medicines in the National Health System’. The reasons were formal: (1) the body that designed the Plan (Comisión Permanente de Farmacia/ Standing Committee on Pharmacy) was not competent; (2) the Plan should have been processed and approved as a formal State regulation; (3) the legal grounds to include economic assessments as part of the IPTs were considered dubious, and (4) REvalMed was not a legally recognised body. After this ruling, the implementation of the IPTs has returned to the Spanish Medicines Agency and no more published IPTs have incorporated an EE.

In the light of this, the MoH now have the purpose to fill the gap and develop a new and comprehensive regulation for HTA. The recent European Regulation (EU) 2021/2282 (European Union, 2021) on HTA gives this opportunity as the development of Joint clinical assessmentsFootnote 8 requires new legislation and organisational measures at national levels. At the EU Regulation, EE is only considered as a field for European voluntary cooperation and not for harmonisation (art 23). However, the Spanish MoH stated in its appeal of consultations in October 2023 that the new regulations will comprise not only the clinical assessment, but HTA at large, presumably including and pushing forward the EE of medicines within this framework (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2023). Following this, a draft of the Royal Decree regulating the evaluation of health technologies in Spain was submitted for public consultation in September 2024.Footnote 9 According to the current draft, the new regulation envisions the configuration of a new organisation to develop Regulation (EU) 2021/2282 on HTA and systematically incorporate EEs in decision-making processes for drugs and non-drug health technologies. The draft anticipates the publication of further guidelines, templates for the dossiers to be submitted by the developers of evaluated technologies, as well as specific methodological and procedural guides. Several issues regarding the content, process and the elaboration of the evaluations under the new system remain to be defined.

In the meantime, the two-year pilot of the 2020 Plan provided us with a unique opportunity to evaluate an experience of incorporating EE for the first time in the drug assessment in Spain. In this study, we analysed to what extent EEs have been incorporated into the Spanish IPTs since this clear commitment was established. We observed that the percentage of IPTs incorporating an EE remained at under 11%.

It is difficult to provide an in-depth quality-assessment of each identified evaluation. The main reason is that, at the time the evaluations were carried out, there were no detailed guidelines specifying the methods to be employed for conducting EEs to inform decision-making on medicines in Spain. The existing brief document (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2020b) provided only general guidance and stated that while specific guidelines were expected to be developed, EEs should follow the methodology outlined in Ortega-Eslava et al., Reference Ortega Eslava, Marín Gil, Fraga Fuentes, López-Briz and Puigventós Latorre2016; a guide developed by the Hospital Pharmacy Spanish Society (GENESIS-SEFH in Spanish). However, it is important to highlight that this guide primarily aims to inform decisions at the hospital level, rather than national-level decisions on drug reimbursement and pricing. A guide for the EE of medicines was developed by CAPF and published in 2023 (CAPF, 2023a), after the two-year pilot. The guide is a recommendation to the Ministry of Health, but has not been adopted by the MoH itself as of today. Nonetheless, these guidelines are expected to provide a stronger methodological framework for future EEs conducted in Spain. Based on this guide, we would conclude that several evaluations analysed in this study do not align with the methodological standards now proposed. Particularly, the potential unjustified use of cost-minimisation analyses, not incorporating all the relevant costs related to the perspective of the analysis, not considering QALYs as a priority for outcome measure, the short time horizons used and the lack of (probabilistic) sensitivity analyses were common findings (see Table 3) that contradict current recommendations. However, it is also worth noting that a number of identified evaluations did follow the standards that are included in the new guide and were comparable to those conducted by other international agencies with more experience in this field. This finding emphasises the large degree of heterogeneity in the evaluations carried out during this period.

Given the non-increasing pace at which EE was introduced in IPTs during the pilot phase, and the substantial heterogeneity in the processes and methods used, it would be premature to deem this period of introducing EE in the evaluation process of medicines as successful. The lack of evaluators, time and other resources allocated to conduct EEs are partly responsible for these outcomes. The Action Plan stated that the pharmacoeconomic evaluation should be performed in a maximum period of 10 days, following the therapeutic evaluation that was expected to be performed within 20 days. These timeframes are clearly insufficient to allow a proper evaluation, which might explain the low methodological standards observed in several evaluations. In addition, the Plan also envisioned that the pharmacoeconomic evaluation was to be conducted after an EE and a budget impact analysis was provided by the company, and that a methodological guide for the pharmaceutical industry to present this information in a standardised manner was to be developed. However, these guidelines were not published and the role and interactions with the industry in the evaluations conducted during this two-year pilot are unknown.

Based on the observed challenges, the analysis of this first experience of incorporating EEs into the drug assessment in Spain allows us to draw a number of lessons and recommendations:

• Political ambitious will is not enough. It is essential to implement an adequate regulatory, organisational and governance framework and sufficient means and specialised human resources to perform the tasks. These issues should be addressed with the new regulation on HTA in Spain now under development.

• Regulations and guidelines should clearly identify the criteria to prioritise the uptake of EEs among the many medicines seeking price and reimbursement every year. Comparative clinical assessments could provide guidance on the degree of need to fund a new medicine. If the drug is considered to have a high budgetary impact and/or if the added therapeutic value is high, then an EE could be prioritised to identify the price range within which the drug would be efficient compared to its alternatives. Such a rule would help focus resources where EEs can generate the most useful information for decision-makers.

• It is also worth highlighting that in many other countries, EEs are typically provided by the companies requesting the inclusion of a medicine in the public benefits basket. These evaluations are then assessed by professionals working for the evaluating agencies themselves and/or external experts appointed by these agencies (Zozaya et al., Reference Zozaya, Villaseca, Abdalla, Fernández and Hidalgo-Vega2022). Introducing a similar process in Spain could offer potential benefits in terms of enhancing the quality of EEs conducted and potentially increasing the number of EEs incorporated into the drug evaluation process. CAPF has recently issued a recommendation in this sense (CAPF, 2023b).

• Additionally, it is crucial to consider the level of evidence available when conducting an EE. Our review revealed that several IPTs did not conduct an EE, and a few more only performed a cost-minimisation analysis. The main reason for this was the lack or insufficiency of data on the effectiveness of the new drug compared to relevant alternatives. Ideally, an explicit criterion linked to the strength and quality of available evidence should be established to ensure consistency in decisions to perform or not an EE and the type of evaluation to be conducted. In addition, clear guidelines on methods required when direct comparisons are not available are needed. These guidelines, and others, should complement the now published Guide on the EE of medicines (CAFP, 2023a).

• Finally, the weaknesses identified in the experience of incorporating EEs in the assessment of drugs also highlight the lack of a coordination of efforts and the missed opportunities to leverage synergies across institutions in charge of evaluating health technologies in Spain, particularly between AEMPS (for drugs) and RedETS (for non-drug health technologies); the latter with a well-established experience in conducting EEs. The current proposal contained in the draft of the Royal Decree retains the separation of the evaluation of health technologies into the existing two separate agencies rather than aiming to create one independent administrative authority. However, the establishment of a new institution that will take the form of a National Health Evaluation Commission (CNEAS) in a medium-to-long term horizon has been proposed (Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Lobo and Vida2023).

In summary, the pilot for incorporating EE into the drug reimbursement and pricing decision-making process in Spain has shown promising initial progress. However, this review highlights concerns regarding the speed of implementation and the heterogeneity in methods and processes. These initial steps provide valuable insights and lessons to guide future improvements in the uptake and performance of EEs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133124000264.

Financial support

LVT acknowledges the funding from RTI2018-096365-J-I00/Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. FL acknowledges funding from Funcas.

Competing interests

Laura Vallejo-Torres declares no competing interests that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Félix Lobo is Chair of the Advisory Committee for the Financing of the Pharmaceutical Provision of the Spanish NHS (Comité Asesor para la Financiación de la Prestación Farmacéutica del SNS).

Juan Oliva-Moreno is an advisor to the Advisory Committee for the Financing of the Pharmaceutical Provision of the Spanish NHS.

The opinions expressed in this article are personal to the authors and do not commit the institutions to which they are linked.