Introduction

The tension between public and private interests as a shaping force in mixed welfare economies is well known (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1990). Nowhere does this tension become more apparent than in public–private health insurance systems, which seem to revolve around a permanent struggle to find the right balance between efficiency and solidarity, between counteracting adverse selection and guaranteeing universal access. The introduction of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 by US president Barack Obama is the most recent example of this struggle. The ACA effectively imposed a new ‘code of conduct’ onto the American private health insurance industry by preventing insurance companies from denying coverage to children due to a pre-existing condition, by prohibiting insurance companies from rescinding coverage and applying lifetime limits on coverage and by regulating the annual limits on coverage (Oberlander, Reference Oberlander2016).

In 2006, the private health insurance industry in the Netherlands, providing voluntary health insurance coverage for (at most) one-third of the population for almost a century, also went through a major reform that profoundly changed the rules of conduct. By this reform, the century-old mixed system of public and private health insurances was exchanged for a mandatory universal health insurance system based on managed competition between health care providers and health insurance companies (Enthoven and Van de Ven, Reference Enthoven and van de Ven2007; Van de Ven and Schut, Reference Van de Ven and Schut2008).

Apart from the United States, there are only a few countries that can provide a well-documented longitudinal case study for the dynamics of public–private interaction in health insurance (Hacker, Reference Hacker2002; Lengwiler, Reference Lengwiler2010). The Dutch case is one of them (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013). In this paper, we will elaborate on the Dutch case, addressing the question how the emerging private health insurance industry tried to reconcile the tension between a competitive insurance market pressuring for selective underwriting and actuarially fair premiums, and an upcoming welfare state pressuring for universal access and socially fair premiums. Furthermore, we examine to what extent the various strategies to cope with this tension were successful and sustainable. We analyzed these questions using a conceptual framework that we built on the influential study by Ewald (Reference Ewald1986) about the shifting concept of risk and insurance in developing welfare states.

Conceptual framework: insurance logic and welfare state logic

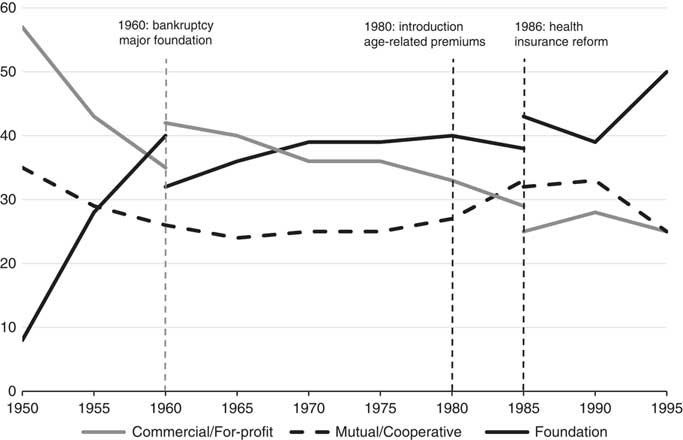

In the Netherlands, a large market for voluntary private health insurance has existed for almost the whole of the 20th century alongside the state-regulated social health insurance system (established in 1941). Until 2006, ~30% of the population in the Netherlands were privately insured (see Figure 1). Nowhere else in Europe private health insurance was so extensive and so important (Colombo and Tapay, Reference Colombo and Tapay2004).

Figure 1 Share of the Dutch population (in %) insured under social and private health insurance, 1935–2005. Source: Vonk (Reference Vonk2013). Note: In 2006, all insurance schemes were replaced by a single mandatory universal health insurance scheme, carried out by competing health insurers (Health Insurance Act of 2006).

Yet, the position of private health insurers was never undisputed. They had to operate in an organizational field in which health professionals, social health insurance funds (known as sickness funds) and the state also had interests. The dynamics of such an inter-institutional field can be analyzed by adopting the institutional logics perspective: private health insurance as a societal field, shaped by competing logics of different institutional orders (i.e. the state and the market). Institutional logics are contingent sets of social norms (cultural rules and cognitive structures) that shape the behaviour of individuals and organizations from a certain institutional order (Thornton, Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2004; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton2012).

In order to analyze how private health insurance in the Netherlands developed over time and especially how this affected the position of private health insurers, this paper employs the conceptual framework of two competing logics in health insurance: a welfare state logic and an insurance logic.

The distinction between both logics is rooted in a fundamental difference in defining the nature of insurance. As Ewald (Reference Ewald1986) pointed out, insurance systems are either based on individual responsibility (the market) or social solidarity (the state). With regard to health insurance, this distinction revolves around the following question: is medical care a source of financial loss or a fundamental right? The insurance logic is based on the idea of insurance as an individual responsibility. Covering health care expenses is people’s own responsibility, and one of the options is to buy health insurance. The main cultural and structural elements of the insurance logic are private-sector administration, free will and limited solidarity (limited accessibility, risk-rated premiums, medical underwriting and so on). By contrast, the welfare state logic is rooted in the notion of social solidarity. Health care expenses should be covered collectively by the state, making accessible health care a civil right. The most important elements of the welfare state logic are, among others, public-sector administration, compulsion, universal accessibility and complete solidarity (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

Both logics are ideal types, the most extreme positions on either side of a continuum. They serve as a heuristic instrument in evaluating changes in predominant visions for insuring health care over time. According to the institutional logics perspective, changes occur through (i) historical events that act as critical junctures and change path dependency by (re)shaping formal structures, introducing new logics or by changing the balance between existing logics; (ii) boundary bridging organizations/individuals (institutional entrepreneurs) that use differences in existing institutional logics to further their own interests; or (iii) structural overlap (i.e. mergers) between organizations with different logics (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Ruef, Mendel and Caronna2000; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton2012). All three elements are at play in the case of private health insurance in the Netherlands.

Methods

This paper uses event history analysis and is based on key primary sources and the extant historiography on socio-economic development of private health insurance in the Netherlands (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995; Companje et al., Reference Companje, Hendriks, Veraghtert and Widdershoven2009; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).Footnote 1 By applying our conceptual framework to the historical timeline, we can distinguish five turning points in the history of private health insurance in the Netherlands in which the balance between insurance logic and welfare state logic changed significantly. These turning points (or crises) were caused by the inherent instability of a specific compromise between insurance and welfare state logic, external shocks (i.e. war, economic recession) or a combination of both. Furthermore, the institutional logic perspective makes it possible to identify key factors of change (historical events, institutional entrepreneurs and structural overlap) for all six periods.

1900–1940: the predominance of the insurance logic

In the period between 1900 and 1940, the insurance logic dominated thinking on health insurance in the Netherlands. Though it was the subject of intense political debate, a political majority of conservative liberals, orthodox Protestants and Catholics supported the view that health insurance was not the duty of the government. Unlike most European countries, the Netherlands therefore did not introduce state-regulated social health insurance (Companje et al., Reference Companje, Hendriks, Veraghtert and Widdershoven2009; Hu and Manning, Reference Hu and Manning2010; Vonk, Reference Vonk2012).

This did not mean that there were no possibilities for Dutch citizens to buy health insurance, yet all forms of insurance were based on voluntary contracts and limited accessibility and limited solidarity. Around 1900, sickness fund insurances dominated the market. They provided insurance aimed at the lower-income groups. Membership was restricted by an income ceiling. The insurance scheme itself was based on service benefits covering pharmaceuticals and services provided by GPs. To this end, sickness funds paid physicians and pharmacists a capitation fee: a fixed payment per year for each enrolled person in their practice (Companje et al., Reference Companje, Hendriks, Veraghtert and Widdershoven2009). Capitation fees effectively transferred insurance risk from sickness funds to providers. For sickness funds this made it easy to predict expenses, and for GPs this implied a guaranteed income from low-income patients. To limit the inflow of high-risk patients, sickness funds applied several instruments to restrict the entry of new members. They only insured people living in a certain ‘service area’, usually a city. High-risk groups, such as the chronically ill, disabled, pregnant and elderly, could not join. Nearly all sickness funds applied a waiting period. However, if money allowed, most sickness funds tried to be lenient when it came to accepting high-risk individuals (Companje et al., Reference Companje, Hendriks, Veraghtert and Widdershoven2009).

During the first decades of the 20th century, sickness funds became increasingly popular. By 1940, roughly 45% of the Dutch population had joined a sickness fund. This expansion was mainly driven by the combination of an economic boom during the 1910s and 1920s, the increased prestige of medical sciences and rising prices for health services. This stimulated both the growth of the potential membership base of sickness funds and the need for health insurance (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

However, this also stimulated the birth of a new form of health insurance. From 1907 onwards, a growing number of not-for-profit and commercial private health insurance companies were established, targeted at the middle-income groups whose earnings exceeded the income threshold set by sickness funds and doctors. Most of these new health insurance companies were mono-line insurers. They offered indemnity-based insurance that covered a comprehensive set of benefits: GP treatment, prescription drugs, hospitalization and specialist treatment. Contrary to sickness funds, private health insurers worked nationwide. Furthermore, they did not conclude contracts with physicians. Policyholders were treated as private patients and got reimbursed afterwards. Instead of an insurance covering the full costs of medical care, policyholders were free to determine the extent of insurance coverage by choosing among different levels of cash reimbursement.

The emergence of private health insurance was supported by the Netherlands Medical Association (NMG), who applauded the fact that private health insurance was built around fee-for-service and indemnity payments. Although the capitation fees paid by sickness funds provided physicians with a guaranteed income, they also came with a price: less professional autonomy, full waiting rooms and moral hazard. The fear was that sickness funds would extend their membership base to the middle- and high-income groups (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

Therefore, the NMG issued a Binding Decree (1912) for all its members, roughly 90% of all Dutch physicians. Members were only allowed to sign contracts with sickness funds that upheld the code of the NMG: restriction of the sickness fund insurance scheme to low-income groups; representation of physicians in sickness fund boards; and the obligation for sickness funds to offer contracts to all physicians in their service area. This effectively split the market for health insurances into a market for sickness fund insurances and a market for private health insurance,Footnote 2 separated by an income ceiling dictated by the NMG.

In the first decades of private health insurance, an actuarial basis for setting premiums was lacking, as the first actuarial studies on health insurance were conducted in Germany only in the mid-1930s (Feddersen, Reference Feddersen1935; Tosberg, Reference Tosberg1936). Though insurers were aware of the threats of adverse selection and moral hazard, the information asymmetry between applicants and insurer was extreme due to a lack of data and appropriate statistical knowledge, which made risk-rating virtually impossible. It is hardly surprising that during the first decades of the Dutch private health insurance industry roughly one-third of all insurers companies were victim of fatal premium spirals, resulting in speedy bankruptcies or take-overs (see Table 1): a classic example of a Rothschild–Stiglitz market (Rothschild and Stiglitz, Reference Rothschild and Stiglitz1976).

Table 1 Establishments, failures and take-overs of private health insurance companies in the Netherlands, 1907–2006Footnote a

Source: Vonk (Reference Vonk2013).

a 1907: first establishment; 2006: introduction universal mandatory health insurance (Health Insurance Act).

In order to keep their insurance plans financially sound, insurers applied crude instruments: stringent risk selection by restrictive pre-existing condition clauses; denying insurance of elderly, chronically ill, handicapped newborns and pregnant women; and non-renewal or even premature cancellation of policies with high claim rates (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995). Keeping high-risk individuals out of the risk pool was not seen as harsh, but as a sign of responsible management and fairness (Kunneman, Reference Kunneman1951). Without such practices, private insurers simply could not survive in the prevailing highly competitive market.

Nevertheless, the NMG was highly critical of the private health insurance industry. They condemned risk selection, the premature cancellation of insurance contracts and the fact that insurers openly professed their ‘pursuit of profit’ (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013). At the same time, local hospital insurance associations, established in rural areas, proved that restricting coverage to hospitalization and specialist care had major advantages. The demand for hospital and specialist care was much less price-elastic and thus susceptible to moral hazard than the demand for primary care and prescription drugs. Furthermore, rural hospital insurance associations did not compete as they only offered insurance to members of their local community. This made these local insurers less vulnerable to adverse selection, and allowed them to adopt a policy of almost open enrolment. As a result, local hospital insurance funds were considerably cheaper and more stable than the traditional more comprehensive private insurers and thus easier to sell (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

The example of the highly successful rural hospital insurance associations was soon followed by large multiple-line insurance companies. During the 1930s, they started to offer the same specialised hospital insurance plans. These companies had a different attitude towards health insurance. Their approach towards health insurance was based on fostering customer relations. Contrary to other insurance products, health insurance usually involved frequent contact between insurer and insured, making it an ideal instrument to build trust and cross-sell more profitable products. This also meant that for multiple-line insurance companies limited losses were acceptable and could be compensated by the profits made in other branches, which enabled them to be more lenient (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

With the entry of larger insurance companies, the market for private health insurance started to grow significantly. By 1940, about 15% of the population had joined a local hospital insurance association and roughly 10% a private (commercial) health insurer (see Figure 1).

1941–1945: the birth of a public–private system and a new logic

Roughly 70% of the Dutch population had some form of health insurance at the start of the 1940s (see Figure 1). According to some, this proved that the Netherlands did not need state-run health insurance: business and civil society were doing the job just as well (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013). Yet, during the 1930s the welfare state logic had taken firm roots in Europe, where governments were increasingly concerned with guaranteeing access to health care (Hu and Manning, Reference Hu and Manning2010). In the Netherlands the welfare state logic was introduced during the German occupation in World War II.

In November 1941, the German occupying authorities issued the Sickness Funds Decree, which established a mandatory social health insurance scheme for wage earners limited by an income threshold and carried out by officially licensed sickness funds. The funds were obliged to accept all eligible applicants (ca. 45% of the population). Sickness funds were allowed to offer voluntary health insurance to the self-employed, as long as their income was below the set ceiling. The benefits of the mandatory scheme covered a broad spectrum of medical care, including hospitalization and specialist treatment. All persons with an income above the set income ceiling had to pay for health care from their own resources or through voluntary private health insurance (Vonk, Reference Vonk2012).

Mandatory social health insurance was financed by uniform state-determined income-related premiums of which both employee and employer paid half. The revenues were collected in a general fund from which sickness funds were retrospectively reimbursed. Hence, sickness funds were not at risk for offering mandatory insurance. This was not the case with the voluntary scheme for the lower-income self-employed. The government had set the rules: open enrolment, no age limits and community-rated premiums and a standard set of benefits. Yet, sickness funds were the primary risk carriers since expenses of the voluntary scheme had to be fully financed by premium revenues. Furthermore, those eligible for the voluntary social health insurance could also opt for private health insurance (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995).

The introduction of social health insurance in the Netherlands had major repercussions for private health insurance companies. They initially lost between half and two-thirds of their insured (see Figure 1). Yet, this did not mean the end of the private health insurance industry. Even though the state did take a more active role in health insurance, the Sickness Funds Decree effectively created a mixed public–private system of social and private insurances with two competing logics centred around the state (welfare state logic) and the market (insurance logic). This external shock profoundly changed the Dutch health insurance landscape, but what remained unclear was whether this system would be maintained after the war (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

1946–1956: insurance logic under fire

Private insurers had ample reason to be worried. During its wartime exile in London, the Dutch government had designed plans for a new system of social security in the Netherlands. A special government committee chaired by Aart van Rhijn advocated the institution of a system of social security based on the welfare state logic captured in the English Beveridge report (Kappelhof, Reference Kappelhof2004). The Van Rhijn plan included a plan for universal health insurance paid for by a mix of taxes and income-related premiums. After the war, however, this plan proved to be politically unfeasible (Companje et al., Reference Companje, Hendriks, Veraghtert and Widdershoven2009; Vonk, Reference Vonk2012).

Despite the failure of the Van Rhijn plan, its underlying principles of solidarity and universal access had gained considerable support. Nevertheless, until the late 1950s private health insurers continued their prewar practices based on the insurance logic, such as non-renewal and the interim termination of insurance contracts and the exclusion of high-risk individuals. In the light of the new welfare state logic, however, these practices were increasingly controversial. Private health insurers became the target of severe criticism in the media and the political arena. Denying or terminating insurance contracts based on pre-existing conditions were no longer seen as instruments of responsible entrepreneurship but as attacks on universal access to health care (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

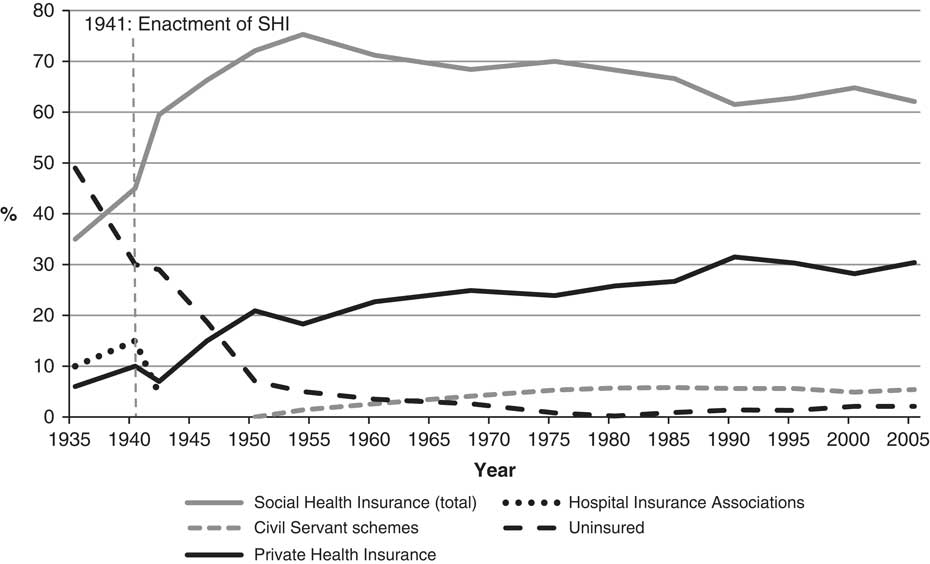

The fact that the private health insurance industry came under closer societal scrutiny fuelled the drive of sickness funds to break through the boundaries of social health insurance. Ever since the introduction of social health insurance in 1941, sickness funds felt that they were ‘reduced’ to mere carriers of a state-run scheme. They aimed to restore a certain degree of autonomy. From 1947 onwards, regional conglomerates of sickness funds started to establish their own private health insurance companies called ‘superstructures’ (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013). In contrast to the existing private health insurers, which were either commercial or mutual companies, these entities were all not-for-profit foundations. By establishing their own private insurers, sickness funds could offer guaranteed access to private health insurance to enrollees that were losing their eligibility for social health insurance due to exceeding the income threshold. Due to the close link with the sickness funds, foundations could benefit from lower administration and acquisition costs and a steady inflow of healthy new policyholders. As a result, they were able to cover a broad range of benefits for a relatively low premium (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013). The superstructure insurance was immensely successful. From 1950 to 1959 the market share of private insurance foundations increased from 8 to 40%, whereas the market share of commercial health insurers dropped from 57 to 35% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Aggregate market shares of the three types of private health insurers, 1950–1995. Source: Vonk (Reference Vonk2013), Schut (Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995).

Foundations were formally separated from the sickness funds, but in practice were run by the same board of directors and used the same administration. Although this violated the intended separation of social and private health insurance, the government was satisfied with the formal split-up. This officially established the right of sickness funds to provide private health insurance. Yet, it also confirmed the right of private health insurance to exist. Government officials were well aware that the existence of a private market was of vital importance for social health insurance. Medical professionals were willing to accept capitation fees and lower prices for medical services under social health insurance, because they were able to compensate this by raising the prices for private patients (Companje et al., Reference Companje, Hendriks, Veraghtert and Widdershoven2009; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

Public and private health insurance started to integrate. The commercial health insurance industry, however, lost out to the sickness funds on two fronts. They did not only lose customers because of the stiff competition from the private insurance foundations, but also due to the expansion of the eligible population for mandatory social health insurance. The strict underwriting practices of private insurers had resulted in increasing social and political pressure to expand social health insurance. This gradual ‘socialization’ of private health insurance was not only disliked by the private insurers themselves but also by the medical association because it reduced the more profitable private practice.Footnote 3 Hence, traditional private health insurers were faced with mounting pressure from both society and the medical profession to relax underwriting stringency. This pressure was reinforced by the success of the private insurance foundations that were better able to accommodate these expectations.

1957–1967: collusion as strategy to bridge conflicting logics

Private health insurance was in crisis. It was clear that a health insurance system in which insurance and welfare state logic were neatly separated was no longer tenable. Something had to change. Traditional private insurers gradually began to adopt elements from the welfare state logic. They realised, however, that this strategy was vulnerable to adverse selection and could only survive if competition would be restricted. In 1957, a group of 30 commercial insurers, including all the major ones, agreed to set up a cartel by issuing a uniform health plan, known as the General Netherlands Health Insurance Policy (abbreviated as ANPZ policy).

The terms of this ANPZ policy were much more beneficial than those of the preceding commercial policies, and could meet the terms offered by the foundations. Specifically, the ANPZ policy covered a broad range of benefits at a community-rated premium, was non-terminable by the insurer, did accept all newborn children irrespective of health status, did no longer use a waiting time for reimbursement at the start of contract period and offered a guarantee of full-risk transfer through unlimited reimbursement of medical expenses instead of fixed indemnity payments. In addition to the uniform ANPZ policy, 35 commercial insurers established a high-risk pool for all substandard risks losing their eligibility for social health insurance. The terms of the high-risk pool contract were largely comparable to those of the ANPZ policy, except that the premium was substantially higher. The losses of the risk pool were evenly spread among all participating companies. Nevertheless, risk selection was not abandoned, as selective underwriting and pre-existing condition clauses were still commonly used (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

By joining a cartel, commercial private health insurers were able to combine the insurance logic with elements of the welfare state logic and managed to compete with the fast-growing private insurance foundations. Furthermore, in due course the private insurance foundations learned that they too could not fully escape the insurance logic. In 1960, the largest insurance foundation (AZR) went bankrupt as a result of adverse selection due to a combination of non-selective underwriting and very low community-rated premiums (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013). AZR’s portfolio was largely taken over by several commercial insurers. This did not only enable commercial insurers to regain some of their lost market share (see Figure 2), but also to strengthen their reputation as responsible and reliable health insurers.

While guaranteed universal access was still a bridge too far, the adoption of important elements of the welfare state logic enhanced the ongoing integration of the commercial health insurance industry into the larger system of health care financing. This integration was not exclusively based on the social ‘U-turn’ the insurance industry had made. The system of ‘hidden’ cross-subsidization between social and private health insurance, especially concerning the prices of medical services, had become another important reason for this. By the 1960s, private patients paid up to nine times higher prices for medical services than patients covered under social health insurance (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013). Social insurance relied on private health insurance to keep prices as low as possible.

In 1967, the government indirectly forced private health insurers to further embrace the welfare state logic, by proposing a national insurance scheme for long-term care that would also include hospitalization and specialist treatment. This caused massive uproar not only among private health insurers but also among sickness funds and physicians. In order to thwart this ‘unholy’ plan, sickness funds and physicians put the pressure on commercial health insurers to solve the problem of risk selection. After all, the existence of risk selection was the main reason the plan got political support. The private health insurance industry buckled and guaranteed universal access through market-wide high-risk pooling via a mutual reinsurance fund (abbreviated as NOZ). By offering guaranteed universal access to health care, the private health insurance industry had effectively removed the main argument underlying the proposed plan. Hospital care and specialist treatment were taken out of the long-term care insurance scheme (the Exceptional Medical Expenses Act, abbreviated as AWBZ) that was enacted in 1968 (Companje et al., Reference Companje, Hendriks, Veraghtert and Widdershoven2009).

The reason behind this fateful step by private insurers was straightforward: health insurance had become too important a product for them to lose. In 1968, private health insurance accounted for roughly 30% of total non-life insurance premiums (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995). The successful incorporation of the most important welfare state principles by the commercial insurance sector was rewarded by an official recognition by the government. In 1968, private health insurers were designated alongside sickness funds as administrators of the new mandatory long-term care insurance scheme. This also implied that private insurers were granted seats on various official advisory and administrative bodies.

The assimilation of the welfare state logic fundamentally changed the nature of the private health insurance industry. It introduced the idea of collective responsibility. A welfare arrangement, based on universal accessibility and broad coverage, could only be achieved in private health insurance through close cooperation. Competition was excluded as far as possible through cartels, a formal consultative structure and informal ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

1968–1985: the limits of solidarity in a private market

For a time, it appeared that a new equilibrium was established. Welfare state logic would predominate in private health insurance too, but the balance between insurance practice and the principles of the welfare state was very delicate. This became painfully clear in the period between 1968 and 1986. The self-imposed code of conduct (welfare state logic) severely limited the room for private health insurers to respond to external events and changing circumstances, such as the cost explosion in health care during the 1970s and the emerging individualization. Self-regulation by private insurers had created a system of universal access, but in due course this system became increasingly exposed to self-induced adverse selection, which gradually undermined the fragile equilibrium. During the 1960s, health care costs exploded after a decade of post-war austerity needed to rebuild the economy. As a consequence, the difference in health care expenses between low-risk and high-risk individuals increased. Since risk-rating was not only socially controversial but also still practically infeasible due to a lack of sufficient data and actuarial knowledge, all private health insurers charged essentially community-rated premiums.

Given the growing dispersion in individual health care expenses, maintaining community rating required increasing cross-subsidies between risk groups. Undifferentiated community-rated premiums made companies with a large share of elderly or other high-risk individuals increasingly less attractive to young, low-risk individuals. Particularly the larger commercial health insurers were suffering from rapidly ageing portfolios and were increasingly threatened by premium death spirals. Meanwhile, the actuarial knowledge of private insurers had increased significantly, especially after the creation of a shared ‘health insurance information centre’, KISG, in 1975. Private insurers gained insight into the variation of individual medical expenses and the associated personal characteristics. This further undermined the delicate equilibrium in the private health insurance market.

Premium differentiation by experience rating seemed to be the next logical step. However, the room for this was limited. At the beginning of the 1970s, the steady economic growth that had lasted for nearly twenty years was beginning stall, resulting in a period of “stagflation”, a combination of economic stagnation and persistently high price inflation (Van Zanden, Reference Van Zanden1998). The government’s strategy to battle price inflation was to impose general limits on price increases. For private health insurers, these price controls limited the room for premium differentiation across age or risk groups. Nevertheless, it is doubtful whether commercial insurers really wanted to differentiate premiums. During the 1970s, serious proposals to introduce a national health insurance scheme were formulated, resulting in 1976 in a draft bill to implement such a scheme. Commercial insurers were well aware that the introduction of risk-rated premiums would give the government all the ammunition it needed to nationalize private health insurance (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

Given that premium differentiation was not fully feasible and politically unattractive, the only possible way commercial health insurers saw to avoid a premium death spiral was to attract low-risk individuals by introducing new insurance policies with high deductibles. At the start of the 1970s, the post-war baby-boom generation was coming of age, and the commercial insurers expected to attract a high number of new low-risk customers by these high deductible plans. This strategy, however, backfired. High deductible policies were soon copied by most other health insurers, with the notable exception of most insurance foundations because deductibles, co-payments and risk-rating were deemed incompatible with the solidarity principles they adhered to. Several small mutual not-for-profit insurers, however, stole a march on commercial insurers. Because of their small and young portfolios, they could match any premium discount offered by commercial insurers and still be more generous. Contrary to commercial insurers who still used agents to sell insurance products, the mutual health insurers had discovered the benefits of direct-writing and had started aggressive marketing campaigns to attract new subscribers (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

In addition, the Dutch Consumers Union became an active player in the market by starting in 1968 to publish overviews of all health insurance premiums and other policy conditions and advising its members to switch to lower-priced health insurers and opt for high deductible health plans. By improving consumer information, however, the Consumers Union unintendedly contributed to the unravelling of the delicate market equilibrium that was created.Footnote 4

The tension caused by the ageing of commercial portfolios led to a restoration of the insurance logic. After the strategy of high deductibles had failed and the political threat of national health insurance scheme had diminished after a change of government in 1977, in 1980 commercial insurers desperately tried to escape from a premium death spiral by introducing age-related premiums. But again they were outmanoeuvred by the mutual insurers who could always offer a lower premium. The growth of mutual health insurers soon eclipsed the growth of all other private health insurers (see Figure 2). Their market share increased, mostly at the expense of the commercial health insurers.

The introduction of high deductibles and age-related premiums marked the beginning of an internal crisis defined by stiff competition and decreasing risk solidarity that swept through the entire health insurance system. Eventually, even foundations started to offer policies with high deductibles, and, subsequently, age-related premiums (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013). This eroded the pillars of the carefully constructed system of health care financing in which public and private health insurance had become institutionally and financially integrated. As a result of the increasing competition in the private health insurance market, the voluntary social health insurance scheme for self-employed collapsed. People insured under voluntary social health insurance were free to opt out anytime, making voluntary social insurance vulnerable to ‘cream skimming’ given that its premiums were community-rated by law. Lured away by cheaper health insurance policies with high deductibles and/or differentiated premiums, low-risk enrolees opted for private health insurance. This led to an increasing share of elderly and high-risk enrolees in the voluntary scheme, which subsequently led to rapidly rising premiums (Schut, Reference Schut and Varkevisser1995; Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

In the 1980s, the voluntary social health insurance scheme was virtually bankrupt. The rapidly worsening risk pool required increasing government subsidies to keep premiums affordable. Therefore, the government brought the private insurers back into line. In 1986, the voluntary scheme was dissolved and its membership base, roughly 2.5 million people, was divided between mandatory social health insurance and private health insurance according to income. The government started to regulate the private health insurance industry to ensure access of high-risk individuals to the private health insurance market. By the Act on Access to Health Insurance (abbreviated as WTZ), private health insurers were required to issue standardised health insurance policies for people over the age of 65 years and other specific high-risk groups at a legally determined affordable maximum premium. Deficits on these standardised policies were pooled and paid for by a uniform surcharge imposed on all privately insured. Hence, elementary principles of welfare state logic (i.e. universal access and risk solidarity) now became legally anchored in private health insurance. Most of the enrolees of the former voluntary sickness fund scheme were automatically transferred to the private foundations that were still closely allied to the sickness funds, resulting in a substantial increase of the foundations market share (see Figure 2) and a further diminishing role of the commercial insurers.

At the same time, the flow of money between private and social health insurance was institutionalised to compensate for the larger share of elderly people within the social health insurance scheme resulting from the reform. A system of mandatory cross-subsidization from private health insurance to mandatory social health insurance was created financed by a mandatory ‘solidarity’ surcharge levied on the privately insured.

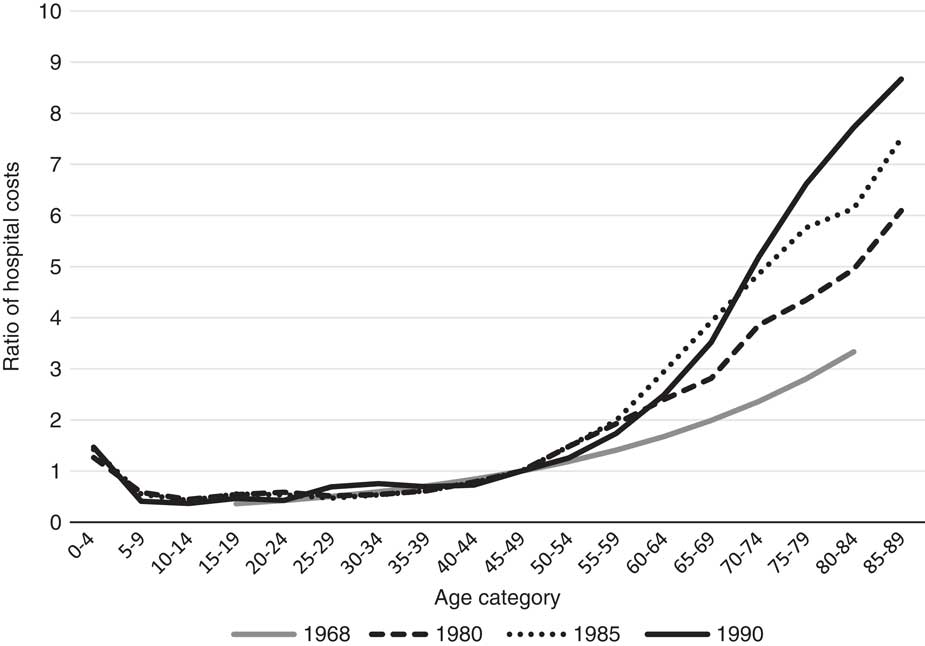

Still, this form of external intervention in health insurance did not address the deeper causes of the accessibility problem of private health insurance: the growing predictable variation in individual health care costs required increasing premium differentiation and increasing surcharges to keep the premium of the standardised insurance policies for the elderly and high-risk groups affordable. As shown in Figure 3, over the years the health care costs at a higher age increased relatively fast, resulting in growing differences in medical expenses across age. For instance, from 1968 to 1990 the average hospital costs of privately insured aged 80–84 years increased from three to about eight times the average hospital costs of those aged 45–49 years.Footnote 5

Figure 3 Ratio of average hospital cost per age category relative to the hospital cost of age category 45–49 for the privately insured in the Netherlands, 1968–1990. Source: De Wit (Reference De Wit1969), KISG (1981, 1986, 1991). Note: The 1968 curve is an estimated Gompertz formula based on data from one of the largest private health insurers (6% market share); the other three curves are based on data from the Health Insurance Information Center (KISG), including data from 55% of the privately insured in 1980, 75% in 1985 and 84% in 1990.

To solve this problem, the government proposed to set up a legally based internal claims equalization scheme (abbreviated as ILPZ) aimed at alleviating the problems of those insurance companies who were faced with rapidly rising costs of ageing portfolios. The organization of this scheme was left in the hands of the private health insurance industry. However, since such a scheme was clearly not in the interest of insurers with a favourable risk portfolio, the private insurers failed to come up with a workable claims equalization scheme (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

This failure provoked further government intervention. In 1991, an amendment of the Act on Access to Health Insurance (WTZ) made the standardised policy open to everyone who paid more for his or her current private health plan than the legal maximum premium that was set for the standardised policy. This amendment provided the government with a powerful instrument to limit private health insurance premiums. From 1990 to 2005, the maximum premium in the private health insurance was effectively reduced from about twice to about 1.5 times the average private health insurance premium (KISG, 1991; Vektis, 2006).

The result was a rapid expansion of the share of the standardised insurance policies, to about one-third of total expenses covered by private health insurance (for about 10% of the privately insured) (Vektis, 2006). Private health insurers did not incur any financial risk on these regulated policies since all deficits were retrospectively compensated from a pool that was filled by mandatory surcharges paid by all privately insured. Therefore, insurers had strong incentives to encourage high-risk individuals to opt for a standardised policy and had no longer any incentives to control the costs of the most expensive subscribers.

The subsequent government interventions in the private health insurance market effectively guaranteed universal access and substantially eased the problems for insurers with an unfavourable risk portfolio. But these interventions also instigated a gradual socialization of the private health insurance industry, paving the way for a more comprehensive reform of the health insurance system.

1986–2006: blending logics – the ascent of managed competition

In 1986, the government decided that a more extensive reorganization of the health care financing system was in order, and appointed a special committee, led by ex-Philips CEO Wisse Dekker. In its 1987 advisory report, soon known under the acronym ‘Dekker plan’, the committee proposed to remove the traditional distinction between public and private health insurance. It should be replaced by a form of standard insurance in which elements of insurance logic and welfare state logic were combined. The Dekker plan proposed a mandatory basic insurance for the entire population, with legislation to guarantee risk solidarity and universal accessibility, including partly income-related and partly community-rated premiums, guaranteed issue and risk equalization. The system also incorporated elements of insurance logic, such as consumer choice among competing insurers and private-sector administration (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

The idea was that adequately managed (or regulated) competition among insurers and care providers would lead to greater efficiency while guaranteeing universal access. Health insurers would be provided with incentives and tools to act as prudent buyers of health care on behalf of their enrolees, instead of being merely administrative bodies or pure indemnity insurers. To that end, health insurers would be able to attract customers by offering better contracts at lower community-rated premiums, and would be allowed to selectively contract or integrate with health care providers. Among health insurers the Dekker plan received mixed reactions. Most sickness funds and private insurance foundations were fervently in favour of the idea. Commercial health insurers, on the other hand, were not enthusiastic at all. In their view, the Dekker plan would mean an extension of social health insurance. Even though the Dekker plan allowed private insurance and profits, health insurance itself would be firmly rooted in the welfare state logic: mandatory insurance, guaranteed issue, standardised benefits, risk equalization and premiums that would be partly community-rated and partly income-related.

Furthermore, if the Dekker plan came into being, nothing could stop the merger of sickness funds and the allied private insurance foundations. How could the relatively small commercial health insurers possibly compete with organizations that insured millions? For commercial health insurers it was of fundamental importance that social and private health insurance remained separated. Still, the private health insurance industry had ran out of possibilities to compensate or adapt. The setup of a legally based internal claims equalization scheme (ILPZ), which could have led to a sustainable and accessible private health insurance market – if it had worked – was torpedoed by insurers themselves (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

In 1992, a first attempt to implement the Dekker plan met with strong resistance from a coalition of employers and private health insurers and further implementation was effectively blocked by the Senate (Helderman et al., Reference Helderman, Schut, van der Grinten and van de Ven2005). Nevertheless, the government managed to implement several crucial changes, which in due course would pave the way for the integration of private and social health insurance. First, consumer choice of sickness funds was introduced by abolishing the fixed regional sickness fund areas. Second, in mandatory social health insurance a community-rated premium was introduced next to the prevailing uniform income-related contribution, covering about 15% of total expenses. Since sickness funds were free to set the community-rated premium, this measure enabled them to compete on price. Third, sickness funds were put at financial risk by the introduction of prospective risk-adjusted capitation payments instead of the traditional full cost reimbursement. Fourth, sickness funds were allowed to selectively contract with outpatient care providers instead of being required to contract any willing provider at uniform conditions. Finally, the existing barriers between social and private health insurance were partly removed by allowing private health insurers to establish their own sickness fund. In the years that followed, private health insurers merged with sickness funds and the latter branched out into private health insurance (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

The Dekker plan heralded the beginning of the end for the commercial private health insurers. The proposed government-controlled market was not one in which the commercial private insurers wished to operate. Moreover, many health insurers realised that they wanted something that was not really possible: fully private insurance that could compete with social insurance in terms of coverage, premiums and accessibility, and also enabled them to make a profit. Consequently, since the mid-1990s, commercial private insurers started to withdraw from the market (Vonk, Reference Vonk2013).

During the 1990s, strict supply regulation to control health care expenditures resulted in growing waiting lists (Schut and Varkevisser, Reference Schut2013). Due to major reforms of workers’ compensation insurance, employers became individually responsible for workers’ compensation during the first year of sickness absenteeism. Hence, employers became more worried about the growing waiting lists than about cost containment. This resulted in a change of position from opponents to supporters of a more market-oriented health care system. As a consequence, the private health insurers, whose position was already weakened during the 1990s, lost a strong ally in their resistance against a fundamental reform of the health insurance system.

The stalled comprehensive reform of the early 1990s had left the health insurance system partially reformed and unstable. Sickness funds and private health insurers operated more or less on the same terms, which made it harder to explain why there was still a distinction between social and private health insurance. The call for ‘real’ reform became stronger and was backed by external support of both unions and employer associations and the growing public discontent about growing waiting lists due to supply regulation. In 2001, the government released a new proposal (Vraag aan bod) with an outline of a new health care and insurance system with similar features as the former Dekker plan (Helderman et al., Reference Helderman, Schut, van der Grinten and van de Ven2005). Five years later, an adapted version of this proposal was finally endorsed by parliament as the new Health Insurance Act (HIA). With the introduction of the HIA in 2006, the Netherlands hit the international headlines. The market-oriented overhaul of the Dutch health insurance system was seen by many observers as a successful effort of deregulation and privatization of a classic welfare system. The old dual system of social and private health insurance was replaced by a universal mandatory health insurance scheme with competing health insurers under private law.Footnote 6

Despite the apparent elements of insurance logic in the new system, most commercial private health insurance companies had already left the market, and the few remaining sold their health insurance portfolio. With its features of universal access, guaranteed issue, risk equalization, prescribed benefits, a combination of community-rated and income-related premiums and income-related care allowances, the new health insurance scheme came closer to a system based on the welfare state logic than a system based on the logic of insurance. As a matter of fact, the HIA effectively incorporated the insurance logic in a framework based on the welfare state logic. This was only feasible due to the development of an increasingly sophisticated system of risk equalization that made it possible to overcome adverse selection problems in a competitive health insurance market with community-rated premiums.

Conclusion

The Dutch history of voluntary private health insurance shows both the strengths and weaknesses of public–private health insurance systems, especially in the context of a rising demand for (universal) access to health care. As we have explained, social and private health insurance are based on two divergent logics of different institutional orders (the market and the state). The intrinsic gap can be temporarily overcome, but it takes measures that are incompatible with and/or contradictory to the idea of entrepreneurship in a free market.

The Dutch case strongly suggests that universal access can only be achieved in a competitive individual private health insurance market if this market is effectively regulated. The tension between adverse selection and universal access that had vexed the Dutch private health insurance industry throughout its existence was resolved by combining elements from both the insurance logic and the welfare state logic: i.e. an individual mandate, guaranteed issue, community-rated premiums, income-related subsidies and a sophisticated risk equalization scheme (Van de Ven and Schut, Reference Van de Ven and Schut2011).

However, the Dutch case also shows this was not done overnight and not always intentionally. The German occupation during WWII was of fundamental importance. It reshaped health insurance and introduced the welfare state logic. During the following decades, state pressure and the work of boundary bridging organizations (the foundations), which acted as mediators between the worlds of social and private health insurance, ensured that private health insurers assimilated the welfare state logic. During the 1980s, increasing structural overlap between the market and the state in health insurance through both legislation and mergers between sickness funds and private health insurers led to the emergence of a new institutional logic (managed competition) in which the insurance and welfare state logic were blended.

A final lesson from the Dutch case is that achieving universal access in a competitive private health insurance market is institutionally complex and requires broad political and societal support. While the US Affordable Care Act (ACA) contains key elements of an appropriate regulation of private health insurance, such as an individual mandate and cross-subsidies, it seems to lack a congruent logic supported by health insurers, medical professionals and state and federal governments. This makes the ACA a vulnerable and incomplete solution (Oberlander, Reference Oberlander2016). This is exemplified by the recent repeal of the federal individual mandate, as approved by US Congress by the end of 2017, which is likely to exacerbate adverse selection and to result in a large increase in the number of uninsured (Congressional Budget Office, 2017). Notwithstanding this, the ACA can also be the stepping stone for the expansion of the welfare state logic. The Dutch case also shows that once a new logic is introduced it is there to stay. In the US, this is illustrated by an increasing number of states that are enacting measures to stabilize the ACA marketplaces, for instance by creating state versions of the individual mandate (Bluth, Reference Boonen and Schut2018).

Whether the tensions between the insurance and welfare state logics in the Netherlands have been permanently settled, however, remains to be seen, as the new role of health insurers as purchasing agents for their enrollees is still disputed and subject of ongoing societal debate (Boonen and Schut, Reference Bluth2011; Maarse et al., Reference Maarse, Jeurissen and Ruwaard2016).