Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

1 Daniel, Robert W., “Two Love Charms,” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 19 (1975) 251Google Scholar.

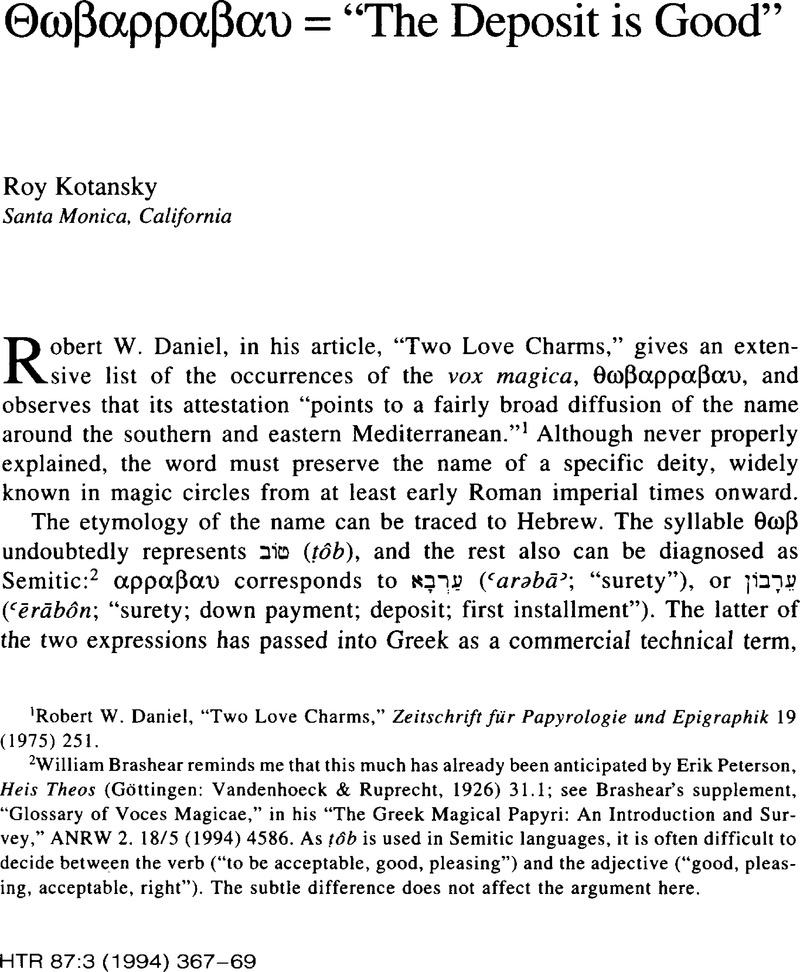

2 William Brashear reminds me that this much has already been anticipated by Peterson, Erik, Heis Theos (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1926)Google Scholar 31.1; see Brashear's supplement, “Glossary of Voces Magicae,” in his “The Greek Magical Papyri: An Introduction and Survey,” ANRW 2. 18/5 (1994)Google Scholar 4586. As ṭôb is used in Semitic languages, it is often difficult to decide between the verb (“to be acceptable, good, pleasing”) and the adjective (“good, pleasing, acceptable, right”). The subtle difference does not affect the argument here.

3 LSJ, s.v. ἀρραβών; see also Masson, Emilia, Recherches sur les plus anciens emprunts sémitiques en grec (Paris: Klincksieck, 1967) 30–31Google Scholar. With regard to the Phoenician root ʻrbn, Masson states (p. 31), “It was possible it passed into Greek via the mediation of Phoenician.” On the numerous forms of the word, see p. 31 n. 5 and the literature cited there; see also Kerr, A. J., “ΑΡΡΑΒΩΝ,” JTS n.s. 39 (1988) 92–97CrossRefGoogle Scholar for a useful review of the social context of the word.

4 With regard to the ending -αρραβαυ, we can compare the Latin equivalents arrabo, arra, or look to the Semitic cognates (see n. 5 below). An equivalent version that preserves a vocalization closer to the Aramaic may linger behind the spelling of the name as θαβαρβα(ωρι), found in PGM 7.204, that is, אכרע כמ (ṭāh ʻar∂hâʼ; “[the] surety is good”). The name is also preserved on the gold amulet from Syria, published by Paul Perdrizet (“Amulette grecque trouvée en Syrie,” REG 41 [1928] 73–82), and reedited in Roy Kotansky, Greek Magical Amulets: The Inscribed Gold, Silver, Copper, and Bronze Lamellae, part 1: Published Texts of Known Provenance (Sonderreihe Papyrologica Coloniensia 22.1; Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1994) 326–30 no. 57. This amulet gives the variants θαυβαρραβαυ) and θωβαρριμαυω; the first may preserve the Aramaic אברע אבפ (ṭābāʼ ʻar∂bāʼ).

5 The variant noun הברע (ʼêerubāh) is also found in 1 Sam 17:18 and Prov 17:18.

6 Philo Fug. 151; τὸν ἀρραβῶνα τοῖτον εἰ καλῶς ἕδωκεν, βασανίξει.

7 Ibid. ῤοπὴ γὰρ εἰ γένοιτο πρός τι τούτων, ὀ ἀρραβὼν οὐ βέβαιος.

8 That is, οὐ βέβαιος ὁ ἀρραβὼν (as in Philo Fug. 151, above) versus ἀγαθὸς ὁ ἀρραβών. Philo further compares (Fug. 152) (again allegorically) an arrabōn of genuine goods (γνήσια μὲν οὖν ἀγαθά) with an arrabōn of those that are counterfeit (κακά … τὰ δέ νὸθα). In normal commercial procedure, as the papyri and inscriptions tell us, the arrabōn is simply “earnest-money,” that is, nonrefundable pledge-monies in the form of coinage; other times, however, we read of other valuables used in exchange, and these presumably would be placed on a scale. In the contract between Tamar and Judah (Gen 38:17–18), these valuables include a ring, a necklace, and a staff.

9 C. Bruston (“Une pierre talismanique expliquee par l'Hébreu,” Revue archéologique, 5th ser., 11 [1920] 47–49, esp. 48) has explained Greek θωβ as Hebrew בופ with regard to another inscription on a gemstone; see also Kotansky, Greek Magical Amulets, 208 no. 38.3.