The Enigma of the Jewish Correspondence with the Spartans in 1 Maccabees

1 Maccabees 12:6–23 cites a letter, allegedly sent by Jonathan, the Hasmonean high priest, to the Spartan state, ca. 144 BCE.Footnote 1 The letter quotes and responds to a previous missive, supposedly written more than a century earlier, from King Areus of Sparta to a high priest by the name of Onias. A Spartan reply, to Jonathan’s brother and successor, the Hasmonean high priest Simon, is cited in 1 Macc 14:20–23.

This suggested third- and second-century BCE correspondence between the Jews of Judea and the Spartans has attracted a great deal of attention in research. The scholarly interest was amplified by the fact that the correspondence suggests a kinship between the two nations, a notion also shared by 2 Macc 5:9.Footnote 2 However, the majority opinion holds that Jonathan’s letter, including Areus’s missive, is inauthentic, for the following reasons (I shall address the Spartan reply to Simon separately, below).

There appears to be no feasible foundation for diplomatic relations between the Jews and the Spartans in the third or second century BCE.Footnote 3 Moreover, Jonathan’s letter seems to discredit the merit of any renewal of friendship between the two nations by informing the Spartans that, although the Jews were obliged to fight many wars, they did not want to trouble their allies and friends over these wars (i.e., they fought them alone), being aided from heaven (12:13–15).Footnote 4

Adding to the confusion is the fact that Jonathan’s letter states that Areus’s missive made “a clear reference to alliance and friendship” (12:8: διεσαφεῖτο περὶ συμμαχίας καὶ φιλίας), yet this is not the case.Footnote 5 It refers only to the brotherhood of the two nations through the family of Abraham (12:21) and appends a declaration about shared livestock and property (12:23).

Arguing, nevertheless, for some purpose behind the correspondence, scholars have resorted to Sparta’s reputation for valor and order.Footnote 6 However, 1 Maccabees’ general hostility to the Greeks does not accord with the adoption of a Greek political or moral model. In other words, the Judean origin and nationalistic nature of 1 Maccabees is at odds with any possible Jewish-Hellenistic, diasporic need for legitimation through association with Greek models.Footnote 7

Furthermore, declaring ethnic brotherhood with the Jews through common descent from a barbarian ancestor would have been unlikely from a Spartan perspective.Footnote 8 The fact that this declaration is based on some “authoritative,” yet unnamed text only adds to the improbability.Footnote 9 Moreover, the earliest mention of the relevant Jewish patriarch, Abraham, in Greek literature dates to the first century BCE, that is, some two hundred years after Areus’s time.Footnote 10

Note also the irregularity in the use of the title of “Spartans” rather than “Lacedaemonians” in this context.Footnote 11 Indeed, 2 Macc 5:9 uses the latter term, as does Josephus in his paraphrase of the correspondence in question (Ant. 12.225–226, 13.166, 170). Most illuminating, in light of the alleged reference by Areus to himself as “king of the Spartans” (1 Macc 12:20), is the inscription at the base of a statue of Areus in Olympia, dedicated by Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt, Areus’s ally in the Chremonidean War. The inscription refers to Areus as “king of the Lacedaemonians.”Footnote 12

Another irregularity lies in the exclusive use of “brotherhood” (ἀδελφóτης—12:10, 17), employed in this correspondence in relation to the Spartan-Jewish kinship. This is atypical usage, from both the Greek and Jewish perspectives.

From the Greek point of view, note, for example, that three sources employ in the same context συγγένεια, the more relevant and usual Greek term in that regard: 2 Macc 5:9; Josephus’s paraphrase of Jonathan’s letter (Ant. 13.167, 169); and Josephus’s quotation of a Samaritan petition to Antiochus IV, which denies their kinship with the Jews (Ant. 12.257, 260). Certainly, the text of 1 Maccabees is a Greek translation from Hebrew and, if authentic, logic dictates that both Areus’s and Jonathan’s letters were composed in Greek: that is, they underwent translation into Hebrew by the author of 1 Maccabees, then back into Greek by the translator of 1 Maccabees. Nevertheless, this still does not explain how συγγένεια, assuming that it appeared in the original Greek text, became ἀδελφóτης, and it certainly does not justify the exclusive use of “brotherhood” in that regard.Footnote 13

From the Jewish perspective, according to Gen 10:2–5 and 11:10–26 respectively, all Greeks are descendants of Noah’s son Japhet, while Abraham descended from another son, Shem.Footnote 14 Moreover, even nations fathered by Abraham’s sons or grandsons with Keturah and Hagar (Gen 25:1–4, 12–15), such as the Midianites and Qedarites, are not referred to in the Bible as “brother” nations.Footnote 15

Finally, Jonathan’s letter declares that the Jews constantly mention their brothers during sacrifices and in prayers, on holidays and other appropriate days (12:11). Such a Jewish practice in relation to the Spartans appears to lack any basis in reality.Footnote 16

As a result of these and additional improbabilities, most scholars conclude that Areus’s missive is inauthentic.Footnote 17 Some, nevertheless, defend the authenticity of Jonathan’s letter,Footnote 18 despite the fact that it shares some strange elements with Areus’s missive, such as the use of “brothers” and of “Spartans” instead of “Lacedaemonians.” Of course, the assumption that Jonathan’s letter is authentic, despite all its peculiarities, entails that the Hasmonean chancellery composed it with a genuine belief in its potential political effectiveness. That, however, leaves us with two untenable options. The first strains the imagination by arguing that the peculiarities are not peculiar after all.Footnote 19 The second accepts as reasonable a certain cluelessness about diplomacy and Greek phraseology among the Hasmonean chancellery, to the extent of sending the Spartans, with earnest, respectful intent, a letter that the Spartans would have most likely considered ridiculous and insolent.Footnote 20

On the other hand, if we acknowledge the dubious nature of the correspondence, we have to query the motive of the author of 1 Maccabees in choosing to cite it. Many suggestions have been raised in scholarly research in that regard, the most frequent being the author’s desire to emphasize the attainment of international recognition, and hence the legitimation of the Hasmoneans.Footnote 21 Other possibilities include a wish to convey Hasmonean continuity with the previous, Zadokite line of high-priests, the Oniads;Footnote 22 “to impress Hellenized Jews into accepting the Hasmonean regime,”Footnote 23 or “to prove the importance of the Jews within the world at large.”Footnote 24

However, as Jonathan Goldstein stated, “a propagandistic forger aims to convince the recipients of his propaganda.”Footnote 25 Contrary to this statement, all the above explanations downplay the fact that the correspondence’s improbability is quite evident. Thus, they only shift the conspicuous incompetence in that regard from the Hasmonean chancellery—according to most scholars who view Jonathan’s letter as authentic—to the forger of the correspondence.

In conclusion, none of the explanations offered for the correspondence is compelling, whether or not it is viewed as authentic. A new perspective is required to solve this riddle.

1 Maccabees’ Use of Fictive Letters and the Proposed Thesis

According to 1 Macc 10:70–73, a Seleucid general named Apollonius sent a message to Jonathan, goading him and urging him to fight on the coastal plain, rather than in the mountains, a terrain which afforded the Jews an advantage.Footnote 26 Contrary to tactical logic, Jonathan accepted this challenge and then proved that the Hasmonean army could defeat the Seleucid force on the plain, too, causing what remained of the Seleucid troops to flee to a nearby city, where they met their death. This course of events replicates a biblical scene—1 Kings 20:23–30. Thus, the episode accords with a dominant characteristic of 1 Maccabees: paraphrasing and alluding to biblical texts.Footnote 27 This trait goes beyond mere mimicry of biblical style, indicating, rather, that the author of 1 Maccabees intended that specific biblical scenes would resonate in the minds of readers, thus placing the Hasmoneans in line with the relevant biblical tradition.Footnote 28 It also indicates that the author of 1 Maccabees envisaged a readership that would include Jews well versed in the Hebrew Bible.Footnote 29 This inference will further serve us below.

In 1 Macc 10:70–73, unlike the biblical model here, Apollonius’s belittling of the Jews’ military capabilities takes the form of a missive (or, at least, an oral message), whose fictiveness is noticeable.Footnote 30 I mention this missive because it joins another letter in 1 Maccabees (10:25b–45), which I have recently argued is a taunt to Demetrius I, a nemesis of the Hasmoneans, upon his downfall.Footnote 31 Fabrication of documents for rivals of the Hasmoneans that present these adversaries as risible is therefore a recurring feature of 1 Maccabees. The Jewish-Spartan correspondence may well constitute another such example, which was not intended to be taken as authentic, at least by the book’s knowledgeable readership. The question remains, however: Who is the object of scorn in this instance? I would like to pursue the possibility that this fictive correspondence with a fictive “brother” nation to the Jews is actually a taunt aimed at a real “brother nation” of the Jews, i.e., not the Spartans but the Samaritans.

Textual Analysis

A. The Samaritan Clue

Let us focus on one sentence in the terse, four-line missive of King Areus of Sparta. The king declares: “your livestock and your property is ours and ours is yours” (12:23a). Timo Nisula regards it as a “rhetoric gesture of common things” and “a good example of the Hellenistic phraseology of friendship.” At the same time, he views the idiom of shared cattle and property as Semitic.Footnote 32 I wish to respond to both parts of Nisula’s statement. First, regarding the “phraseology of friendship,” one has to admit that something appears innately wrong in the structure of this sentence. Take, for example, the known idiom of hospitality: “my house is your house.” If you reverse the order of the possessive pronouns and place the entire saying in the mouth of the guest, rather than the host, it has a very different meaning, one of covetousness and usurpation: “your house is my house.”Footnote 33

Regarding the “Semitic” origin of the reference to shared cattle and property, there is indeed a single, similar expression in the Bible in the context of an alliance between two kings but, as would be expected, it is couched in the proper, tactful manner: “my horses are as your horses” (1 Kgs 22:4; 2 Kgs 3:7).Footnote 34

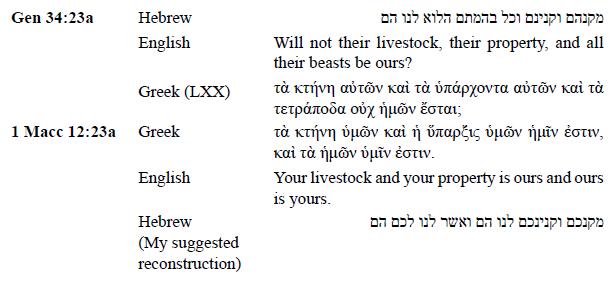

However, there is also a single biblical example of the form of phrasing that we find in 1 Macc 12:23a, which reveals a greedy expectation of gaining property as a result of the proposed alliance. Moreover, this example is set in a highly relevant context, that is, one relating to the creation of an alliance between a foreign nation and Israel. Having just seen that paraphrasing and alluding to specific biblical texts is a literary convention in 1 Maccabees, let us compare the text under discussion of 1 Maccabees with this biblical reference. Given that the extant text of 1 Maccabees is a Greek translation from Hebrew, the two ancient Greek translations, i.e., the Septuagint and 1 Maccabees, lie at the heart of the following comparison:

Certainly there are some differences. The possessive pronouns are in the third person plural in Gen 34:23a and in the second person in 1 Macc 12:23a; Gen 34:23a divides the livestock into two groups by adding “all their beasts,” and 1 Macc 12:23a adds the reciprocal aspect of shared property (“ours is yours”).Footnote 35 Nevertheless, even without suggesting that the Greek translator of 1 Maccabees was necessarily aware of the biblical reference made here, the close similarity between the two literal Greek translations from Hebrew appears to be a matter of fact.Footnote 36

To state it unequivocally: the original Hebrew of 1 Maccabees in this sentence must have resonated in the mind of every reader familiar with the well-known biblical text of Gen 34, in which a proposed alliance between Israel and the Shechemites, conditioned upon the latter’s circumcision, sets the background for the killing of all the male Shechemites by Jacob’s sons. The popularity of this biblical tale in the Hellenistic period—below, we shall explore several references to Gen 34 in pertinent Jewish compositions—allows us to assume that many of 1 Maccabees’ intended readers were familiar with the text of Gen 34 and were thus able to decipher the literary encryption of the correspondence with the Spartans. The correspondence’s congruence with 1 Maccabees’ predilection for echoing specific biblical texts through paraphrase and allusion would further suggest that the author of this correspondence and the author of 1 Maccabees are one and the same.

However, why put the greed-motivated incentive for an alliance with Israel, voiced by the Shechemites in the famous biblical story of Gen 34, in the mouth of a Spartan king addressing the Jews? The answer is that at least in the Hellenistic period, if not earlier, Gen 34 was viewed by Jews as referring to the people of Shechem of their own time, i.e., the Samaritans.Footnote 37 The conclusion suggests itself: 1 Maccabees writes of Spartans but envisions Samaritans.

Credit is also due to Adolf Büchler, who, more than 120 years ago, compared the correspondence’s statement to the effect that the Jews mention their brothers in their prayers (12:11), as well as the overall emphasis on brotherhood, with the opening letter of 2 Maccabees. The latter is addressed “to the Jewish brothers in Egypt” (1:1) and further declares that their Jewish brothers in Jerusalem and Judea are praying for them (1:6). Büchler therefore concluded that Jonathan’s letter could only have been written to either Jews or Samaritans.Footnote 38

B. The Enigma Resolved

Note how the view of the Spartans as an alias for the Samaritans explains all the discrepancies in the text. First, the use of “brothers” in the correspondence rather than “kin,” which seems strange in relation to the Spartans, makes perfect sense in relation to the Samaritans as descendants of the Ten Tribes. In fact, in another second- or even third-century BCE Jewish text referring to Gen 34, namely, the Aramaic Testament of Levi (1:2–3), the sons of Jacob offer the Shechemites the opportunity to become “brothers and friends” (א[חין] וחברין … א[חין]).Footnote 39 Evidently, this language is identical to that in the correspondence under discussion.

Second, as mentioned above, Jonathan’s letter states that Areus’s missive made “a clear reference to alliance and friendship” (12:8), whereas the missive merely states that the nations are related through Abraham.Footnote 40 If by employing “Spartans” the correspondence actually refers to the Samaritans, this incongruity is resolved, because it opens the possibility that the original Hebrew word ברית in 1 Macc 12:8 (or בעלי ברית in v. 14—compare with Gen 14:13) should probably not have been translated in the sense of a military alliance (συμμαχία) but, rather, as a covenant, as used in Amos 1:9, “the covenant of brothers” (LXX: διαθήκη ἀδελφῶν), or even the Abrahamic covenant of circumcision shared by Jews and Samaritans.Footnote 41

Third, while implausible in relation to the Spartans, the statement to the effect that the Jews constantly mention their brothers during sacrifice and in prayer (12:11) is perfectly reasonable in relation to the Samaritans. As descendants of the Ten Tribes, it might be argued that they are included by implication in Jewish liturgy and holiday hymns, whenever the term “Children of Israel” appears.

Fourth, the use of ספרטנים/שפרטנים (if I may reconstruct the Hebrew of 1 Maccabees here) rather than לקדימונים could derive from the fact that the former is somewhat closer in spelling and pronunciation to שמרנים. The name “Samaritans,” following a biblical hapax legomenon (2 Kgs 17:29), appears in the New Testament and Josephus.Footnote 42 If, indeed, a certain similarity, in Hebrew, between Samaritans and Spartans underlies 1 Maccabees’ use of the latter term, it constitutes far earlier textual evidence for the use of the term “Samaritans” among Jews.

Fifth, Areus states that he found the reference to the two nations’ “brotherhood,” from the stock of Abraham, “in writing” (12:21). If the “Spartans” are actually Samaritans, the identity of this “writing” is clear: the Hebrew Bible.

C. An Allusion to the Gibeonites of the Book of Joshua or the Amorites of an “Addition” to the Book of Genesis?

Perhaps Gen 34 is not the only biblical or extrabiblical text to which this correspondence alludes. Note that Jonathan’s statement that “the surrounding kings made war against us” (ἐπολέμησαν ἡμᾶς οἱ βασιλεῖς οἱ κύκλῳ ἡμῶν—12:13) is anachronistic in its use of “the surrounding kings.” Other than the Seleucids, the relevant nations and cities against which the Hasmoneans fought were not ruled by kings but by local chieftains or Seleucid officers.Footnote 43

I can think of two biblical or extrabiblical traditions that might explain this use of “the surrounding kings” in the context of war. One tradition is that of Joshua’s wars and the Gibeonites. The phrase “the surrounding nations” appears four times in chapter 5 of 1 Maccabees (5:1, 5:10, 5:38, 5:57), which narrates the Hasmonean wars, under Judas Maccabeus, in Transjordan, the Galilee, and the Negev, as well as against the cities of Hebron and Azotus.Footnote 44 Jonathan Goldstein and Ernst Knauf observed that this chapter portrays Judas as Joshua.Footnote 45 Indeed, in chapters 9–11 of the Book of Joshua, we encounter consecutive wars with various surrounding—i.e., neighboring—kings. The text even exhibits similarity to Jonathan’s letter by stating that Israel won these wars because God fought for them (Josh 10:14, 42; compare with 1 Macc 12:15). Significantly, within this narrative in the Book of Joshua, there is a well-known episode describing how the Gibeonites approached Israel under false pretenses, seeking to form an alliance (ברית = διαθήκη in the LXX to Josh 9:6, 7, 11, 14, 16). Perhaps by mentioning the wars with the surrounding kings and God’s aid in these wars, 1 Macc 12:13–15 is alluding to this biblical episode regarding the formation of a deceitful alliance with Israel.

The other tradition is that of the wars of Jacob and his sons in Samaria. Jubilees 34:1–9, the Testament of Judah (chapters 3–7), as well as the medieval rabbinic midrashim Yalkut Shimoni (to Gen 35:5) and Midrash Vayissaʿu (chapter 2), preserve an extrabiblical tradition that explains why, contrary to Jacob’s expectation in Gen 34:30, the “surrounding cities” (LXX—αἱ πολεῖς αἱ κύκλῳ αὐτῶν), mentioned in Gen 35:5, did not pursue Jacob’s sons following the massacre in Shechem. The explanation, relying on an otherwise obscure verse in Gen 48:22, is that Jacob and his sons actually fought against these Amorite cities and their kings and defeated them. As offered in research, and as can be expected from the context, the relevant cities lie in the vicinity of Shechem in Samaria. It was therefore suggested that this tradition represents an extra anti-Samaritan Jewish polemic, in addition to Gen 34.Footnote 46 Note that according to T. Jud. 7:7, and the rabbinic versions of the tradition, following the wars with the relevant kings, the Amorites/Samaritans begged Israel (Jacob) for peace. It is possible that the author of 1 Maccabees hints at that tradition in the context of a Samaritan offer of friendship made to the Hasmoneans.

Scorn for Jonathan, alongside the Samaritans?

The correspondence’s scorn of the Samaritans, veiled as Spartans, is therefore manifest in the following innuendoes and messages:

1. Recall the reasons that propelled the biblical Shechemites into a bond with Israel (as narrated in Gen 34:21–23)—i.e., Israel’s richness (and daughters).

2. As Jews, we possess the same holy books (“in our hands”), so the Samaritans need not remind us about this “brotherhood” of ours. We remember it constantly in our liturgy (whenever we mention the Children of Israel). However, where were the Samaritan “brothers” during our recent wars?Footnote 47

3. With God’s help, we overcame the surrounding kings. Only then was this bond evoked, thus recalling the Gibeonites who approached the victorious Joshua deceptively, or the Amorites/Samaritans who approached the victorious Israel (Jacob) after defeat at his hands and those of his sons.

Assuming, however, that the decision by the author of 1 Maccabees to place the correspondence in the context of Jonathan’s high priesthood is not arbitrary, we should ask whether Jonathan is also being criticized for responding to Areus’s missive and offering to renew the ties between the two nations. Note that after receiving the (likewise fabricated) letter of Demetrius I, Jonathan and the people rejected “Demetrius’s offers” unconditionally (10:46). It is true that in Gen 34, 1 Maccabees’ relevant biblical model, Jacob’s sons also responded to the Shechemites’ offer (vv. 8–12). However, Gen 34:13 makes it clear that this was a ruse.

In comparison, Jonathan’s letter portrays him as an earnest negotiator, albeit unenthusiastic: he suggests a renewal of the (ties of) brotherhood and friendship (12:10, 17) but then downplays the value of alliance and friendship, compared with the “holy books” (12:9),Footnote 48 and adds that he writes only to prevent the two nations from becoming estranged (12:10).Footnote 49 Likewise, he points out that the Jews constantly mention their brothers in their liturgy and rejoice in their glory (12:11–12), but then he adds, “heaven is our aid” (12:15).

It should be recalled that 1 Maccabees buttresses the dynastic claims of Simon’s descendants. A softened reproach, therefore, of Jonathan’s willingness to negotiate with the Spartans/Samaritans would accord with a certain ambivalence of 1 Maccabees toward Simon’s brother and immediate predecessor as high priest and Hasmonean leader. On the one hand, 1 Maccabees mentions Jonathan in the honorary decree for Simon (14:30), in comparison with Judas, who is not mentioned specifically. On the other hand, as pointed out by Daniel Schwartz, this reference actually belittles Jonathan by summing up his 18 years of military, political, and religious leadership in the following sentence (note the wordplay by using the same verb twice): “Jonathan gathered his people and became high priest and was gathered unto his people” (14:30).Footnote 50 Also, at face value, 1 Maccabees attempts to exonerate Simon from sending Jonathan’s sons to Tryphon (13:17–19), to their death. However, as pointed out by Uriel Rappaport and taken further by Johannes Bernhardt and Benedikt Eckhardt, this attempt is not very convincing, and even yields the impression that Simon seized the opportunity to clear the way for his sons, perhaps as far as cooperating with Tryphon.Footnote 51

1 Maccabees’ Replacement of Samaritans by Spartans and the Spartan reply to Simon (14:20–23)

From a literary and structural point of view, once the author of 1 Maccabees decided to blur the contact with the Samaritans by replacing them with the Spartans, he saw no better place for it than in the context of Jonathan’s international relations, that is, along with his renewal of the Hasmonean ties with Rome. His choice of the Spartans, however, of all possible foreign nations, had three possible incentives. First, he was apparently aware of the (diasporic) Jewish-imagined notion of kinship between the Spartans and the Jews, which also appears, as mentioned, in 2 Macc 5:9. Second, Sparta was a foreign nation on a par with Rome, in the sense that it was somewhat remote, yet renowned and familiar. Third, as already suggested, perhaps a certain similarity between the names “Spartans” and “Samaritans” appealed to him.

After designating the Spartans as an alias for the Samaritans, the author of 1 Maccabees sought a known Spartan leader to whom he might ascribe the initial contact with the Jews. He opted for the illustrious Areus, thus creating a considerable hiatus between this contact and Jonathan’s reply. At the same time, it is questionable whether the author of 1 Maccabees was necessarily aware of the fact that the interval between Areus’s death and Jonathan’s alleged reply was that long, namely, 121 years. It nevertheless remains that the Spartans, i.e., the Samaritans, apparently initiated the contact with the Jews. The last identity left for the author of 1 Maccabees to allocate was that of the high priest who ostensibly received Areus’s missive. The author chose Onias, a recurring name among the high priests of the third century BCE.

1 Maccabees’ basic decision in this context, however, was to allude to the Samaritans as Spartans, rather than mock them directly, as it does in the fabricated letter that it attributes to Demetrius I (10:25b). In reply, it could be argued that Gen 34 represented for the author of 1 Maccabees a biblical model for an implicit criticism of the Samaritans in a story about a different national group (the Shechemites). That being said, the above-mentioned criticism of Jonathan may have posed a more practical reason for this disguise. Namely, the fact that the author camouflaged that criticism may disclose misgivings about openly criticizing Jonathan. Once the Samaritan affair was thus encrypted, however, the author must have realized that the correspondence would have two distinct groups of readers. The first group consists of those who would grasp the reference to the Samaritans through the allusion to Gen 34 and, therefore, also sense the criticism of Jonathan—albeit, slightly mitigated for those readers by presenting Jonathan as unenthusiastic about the alliance. The second group consists of those who would not grasp the reference to the Samaritans, and thus regard this episode as actually acclaiming Jonathan’s international achievements. For such readers, Jonathan’s distinct lack of enthusiasm, along with the many other incongruities in the text, remained a puzzle.

Let us now turn to the final letter of the correspondence, the “Spartan reply” to Simon. In my view, it strengthens the impression of two distinguished, intended readerships.

This “Spartan reply” is but a clerical note, which evinces no knowledge of any former or special relationship with the Jews.Footnote 52 Moreover, it contains no response to the content of the suggested Hasmonean offer of a renewal of friendship (1 Macc 14:22—φιλία—i.e., neither brotherhood nor kinship).Footnote 53 It is as if the author of 1 Maccabees wanted to checkmark a “Spartan” letter to Simon, regardless of its content. Indeed, the honorary decree for Simon—an authentic document cited by 1 Maccabees—does not mention the Spartans in referring to the international recognition of Simon (14:38–40). Clearly, this “Spartan reply” cannot be read as a clandestine criticism of the Samaritans. Therefore, how can we explain it? The answer is that it served those readers who were unaware of the hidden scorn in Jonathan’s letter to the Spartans. Since Jonathan reached out to both Rome and Sparta (12:1–23), the Roman acknowledgment of Simon’s succession of Jonathan (and Judas—14:17–18) had to be accompanied by a similar acknowledgment on the part of Sparta. Otherwise, Simon would have been presented as falling short of Jonathan, in terms of his international reputation.

The Historical Plausibility and Implications of a Samaritan-Hasmonean Contact

Jonathan’s letter attests to a certain degree of confidence on the part of the Hasmoneans, declaring that they had humbled their enemies (12:15). Moreover, 1 Macc 12 opens by stating that Jonathan saw that time was working in his favor (12:1). Indeed, according to 1 Maccabees’ narrative, Jonathan sent his letter to the Spartans after gaining the recognition of Ptolemaic Egypt,Footnote 54 as well as gaining key territories through military force (for example, the capture of Beth-Zur—1 Macc 11:66) and by exploiting recurring struggles between different contenders to the Seleucid throne through international negotiations. An example of the latter are the three districts, formerly part of Samaria, which the Hasmoneans received from Demetrius II (1 Macc 11:34). It is not unreasonable to assume that, at this point, the Samaritans had a stronger incentive to reevaluate their interests in the Hasmonean-Seleucid conflict. We can also guess that it was in Jonathan’s strategic interest not to turn the Samaritans into direct rivals. This concern shifted when 1 Maccabees was composed (per consensus) under Hyrcanus,Footnote 55 thus triggering the ironic presentation of the correspondence.

Regarding possible implications to be drawn out of this ironic correspondence for the date of 1 Maccabees, I can only point out that the thought of an alliance with the Samaritans would have been more ironic after their actual defeat and the destruction of their temple by Hyrcanus.Footnote 56

Brotherhood and Resentment Reconciled

After suggesting that the correspondence under discussion derides the Samaritans, we must address its reference to them as “brothers.” Apparently, there was no inherent contradiction between this usage and the prevailing Jewish hostility toward them. Indeed, several Jewish sources from the Hellenistic period, and the second-century BCE, in particular, exhibit resentment toward the Samaritans:Footnote 57

1. Whereas Gen 34:7bα reads: כי נבלה עשה בישראל “for he (Shechem) had wrought villainy in Israel,” T. Levi 7:2–3a terms the city of Shechem “a city of fools” (πόλις ἀσυνέτων) and explains: ὅτι ὡσεί τις χλευάσαι μωρὸν οὕτως ἐχλευάσαμεν αὐτούς˙ ὅτι καίγε ἀφροσύνην ἔπραξαν ἐν Ἰσραήλ, “because as one mocks a fool, so we mocked them, for they had truly wrought folly in Israel.”Footnote 58

2. Ben Sira 50:25–26:איננו עם גוי נבל הדר בשכם += not a nation + a villainous nation that dwells in Shechem.Footnote 59

3. 4Q371 1 + 4Q372 1 line 11 + 20: נבלים + עם אויב = villains + an enemy nation.

4. 11Q14 2 line 1: הגוי הנב[ל] = the villainous nation.

5. Τhe epic poem of Theodotus, fragment 7 (Eusebius, PE 9.22.9b), refers to the people of Shechem as “godless (ἀσεβεῖς), who are engaged in deadly deeds (λοίγια ἔργα).”Footnote 60

At the same time, the ethnic brotherhood of the Samaritans and the Jews appears in both 1 and 2 Maccabees, as well as in Josephus.Footnote 61 They all mention that the Seleucids, under Antiochus IV (2 Macc 5:23, 6:2; Ant. 12.257–264) and Demetrius II (1 Macc 11:34), considered the Samaritans to be part of the nation (τὸ γένος—2 Macc 5:22) of the Jews (2 Macc 6:1) and that the two communities were mainly distinguished by the temples where they worshiped—either in Jerusalem or on Mount Gerizim.Footnote 62 The fact that these Jewish sources do not criticize the Seleucid view suggests that this stance was also acceptable to Jews.Footnote 63 However, if the correspondence in question refers to the Samaritans, this perspective is no longer inferred solely through the absence of any Jewish objection to the Seleucid position in the texts of 1 and 2 Maccabees and Josephus. In other words, contrary to the previous “argument from silence” in that regard, Jonathan’s letter could be seen as explicitly acknowledging the Samaritans’ brotherhood with the Jews.

Jonathan Bourgel suggests that Ben Sira’s reference to the Samaritans as “not a nation” (50:25) also indicates a perception of the Samaritans as not entirely separate from the Jews.Footnote 64 Bourgel, furthermore, posits in that light the destruction of the Samaritan temple by John Hyrcanus and the Hasmonean wish to restrict the worship of the Samaritans to the Jerusalem temple, that is, as indicative of a Jewish perception of the Samaritans as Israelites.Footnote 65

Conclusion

The implausibility of the Hasmonean-Spartan correspondence suggests that it was not intended to be taken literally. This observation pulls the rug out from under the binary (and unsatisfactory) view of Jonathan’s letter in research: either as an incompetent and unconvincing fabrication, designed to enhance the prestige of the Hasmoneans/Jews, or as an authentic diplomatic initiative, notwithstanding its many inconsistencies and irregularities that would have been far more likely to thwart any possible relationship with the Spartans than to establish one.

The resemblance of Areus’s offer of alliance to the LXX text of Gen 34:23a, in both language and the unusual tactless construction, suggests a taunt at the Samaritans. Following this keystone, the entire enigma is decoded, and all the otherwise seemingly discordant elements of Jonathan’s letter fall into place, aligning in one direction.

Thus, the use of אחים וחברים is identical to the reference to the Samaritans, found in the Aramaic Testament of Levi; the constant references in Jewish liturgy to the Children of Israel include the Samaritans, as descendants of the Ten Tribes; the Bible emerges as the “writing” that attests to the brotherhood of the two nations; and, finally, the ברית between them is a covenant rather than a military alliance. Even the choice of “Spartans,” rather than “Lacedaemonians,” may have been designed to help grasp the allusion to the Samaritans. An underlying sarcasm toward the Samaritans is consistent with their negative image and portrayal in other Jewish texts of the Hellenistic period and the second century BCE in particular, the implicit (and, if I am correct, now explicit) recognition of their ethnic brotherhood notwithstanding.

Rather than being a poorly crafted document, whether fabricated or authentic, Jonathan’s letter presents an ingenious work of fiction. Like other ironical, fake documents in 1 Maccabees—i.e., the letter of Demetrius I and Apollonius’s message to Jonathan—it was designed to entertain by satirical criticism of a contact, apparently made under Jonathan, with the Jews’ authentic ethnic brothers, the Samaritans. Moreover, in this text the author successfully combines two literary devices, common in 1 Maccabees: paraphrase of biblical texts and the fabrication of letters. Congruence with these two attributes in 1 Maccabees strongly suggests that the author of this specious correspondence and that of 1 Maccabees are one and the same.

However, unlike the letter of Demetrius I and Apollonius’s message to Jonathan, here, the identity of the non-Jew approaching the Jews is veiled. Rather than a Samaritan (a real ethnic brother), he is depicted as a Spartan (a fictive, ethnic brother). My suggestion is that this disguise resulted from the author’s reluctance to criticize Jonathan directly. Under Simon’s son, Hyrcanus, an alliance with the Samaritans was no longer advantageous to the Hasmoneans, perhaps even risible, if indeed 1 Maccabees was composed after Hyrcanus subdued them. However, openly criticizing Jonathan for a past attempt of negotiation with the Samaritans was apparently still a far too sensitive move for the author of 1 Maccabees. This suggestion also accords with the book’s ambivalence toward Jonathan. However, as a result of the disguise of the Samaritans as “Spartans,” two readerships have been envisioned by the author: those who, aided by the biblical paraphrase, would grasp the irony, and those who would not. The improbable “Spartan” letter to Simon appears to serve the latter readership.

Deciphering the enigma of the correspondence with the “Spartans” offers a glimpse into the political leadership of Jonathan, who overcame past resentments in negotiating with his rivals, the Seleucids, and apparently adopted a similar approach toward the Samaritans. This leads us to wonder whether the relationship between the two brother nations might have turned out differently, had he not been killed shortly thereafter.

Appendix: An Insight into the Literary Nature of 1 Maccabees

A. Laughs within Serious Historiography?

Irony and wit are not absent from ancient Jewish historical fiction, as demonstrated by Erich Gruen.Footnote 66 He focused, in particular, on humor in works relating to the lives of Jews as ethnic and religious minority communities in the Diaspora, beginning with the Book of Esther. While 1 Maccabees, too, recounts the deliverance of a small ethnic group from a hostile foreign power (as well as from the surrounding nations), it was composed and compiled in the independent, expanding Jewish state of Judea. Its lampooning of the Hasmoneans’ foes, therefore, probably does not, “open an avenue into the mentality of Jews adapting to a world of alien culture and Gentile overlords.”Footnote 67

What stymied research from realizing the extent of the irony in 1 Maccabees appears to be the fact that modern readers rigidly categorize this composition as “history”—whether fabricated or authentic. Undoubtedly, a considerable gap exists between 1 Maccabees and ancient Jewish works of evident pseudo-history, such as the Book of Esther. True, Gruen adds that “even serious historiography (as in 2 Maccabees) could be enlivened by novel touches that slipped into comedy,”Footnote 68 but his choice of 2 Maccabees as an example of serious ancient Jewish historiography embellished with humor only strengthens the case for overlooking the humor in 1 Maccabees. The reason is that 2 Maccabees’ blatant penchant for overdramatization, graphic description, exaggeration, and falsification has contributed to the low regard for its historical value, and therefore, in light of its habitual alignment against 1 Maccabees, reinforced the perception of the latter as a work of history of more serious caliber.Footnote 69

B. Varying Degrees of Pseudo-Documentarism: Another Comparison with 2 Maccabees

To be sure, 1 Maccabees’ humor is not straightforward, being mainly expressed through ostensibly official documents.Footnote 70 As such, it may be termed pseudo-documentarism, following the definition of Karen Ní Mheallaigh: “A strategy in which an author claims—with varying degrees of irony—to have discovered an authentic document which he transmits to his readers.”Footnote 71 Mheallaigh, however, examined the use of allegedly authentic documents in ancient fiction, whereas 1 Maccabees represents the use of fictional and ironical documents in ancient historiography. Arguably, this type of pseudo-documentarism is harder to detect, because documents cited in a historical work are presented as “hard evidence” that did not pass through the historian’s interpretative, biased prism. However, ancient standards of historical “accuracy” differed in that respect. In the words of Angelos Chaniotis: “[Greek] historians used fictitious orations and constructed documents in order to vivify the historical narrative. The fabrication of a document corresponds to the principle of enargeia (vividness) that characterizes Greek oratory and historiography.”Footnote 72 Perhaps, therefore, an ancient audience of Jewish historiography, such as 1 Maccabees, would have also been less surprised than modern readers at its literary license through the use of ironic, fictitious documents. There are, of course, differences of degree in that respect. It is sufficient to compare, in that context, the correspondence under discussion with a fake letter in 2 Maccabees, allegedly written by Antiochus IV on his deathbed (9:19–27). The content of this letter is so preposterous that its pointed satire is incontestable.Footnote 73

In conclusion, despite the distinct sophistication of the ironical letters in 1 Maccabees, and the encrypted correspondence under discussion in particular, they appear to bolster David Williams’s advice: “Scholars who approach 1 Maccabees should be open to considerations of literary artistry within the book, in addition to the historical information which it provides.”Footnote 74 Indeed, the cloaked sarcasm in this correspondence reveals an additional dimension of the author’s artful use of biblical texts and biblical models, and it deepens our understanding of the literary creativity embedded in this important historical composition.