Introduction: Revisiting Intertextuality in Job

Many interpreters have argued that the book of Job displays an intertextual dialogue with the Torah, Prophets and Writings of the Hebrew Bible.Footnote 1 Some hear Job’s test as an echo of Abraham’s (Gen 22); notably, both are approved as loyal worshippers of Yhwh who offer a burnt offering on behalf of their children.Footnote 2 In Job’s initial lament, his wishful cry for darkness (חׁשך יהי, Job 3:4) can be heard in place of God’s effective command for light in the Priestly creation account (אור יהי, Gen 1:3).Footnote 3 The portrait of Job, including his death “old and full of days” (Job 42:17), is thought to be reminiscent of the Patriarchs of Genesis.Footnote 4 Furthermore, many perceive in Job a reconsideration of the Deuteronomic model of blessings and curses (Deut 28),Footnote 5 while Raik Heckl argues that the Joban framework alludes to 1 Samuel 1–4 (DtrH) and thereby acts as a sort of “counter-history against the deuteronomistic theology of history.”Footnote 6 Others have contended that Job interfaces with both the Deuteronomic and the Priestly traditions of the Torah, presenting on the one hand a “critical debate about the understanding of God in Deuteronomy,”Footnote 7 and on the other, “a critical evaluation of the theocratic order of the Priestly Code.”Footnote 8 Yet, others would retort that Job cannot be reduced to a categorical critique of either D or P, because “Leviticus’ general reflection on God’s justice reaches forward to the Book of Job,” since, in the end, neither Leviticus nor Job resolves theodicy, but rather omits theological explanations for misfortune, disease, and barrenness.Footnote 9

Many of these studies claim that Job relates intertextually to other texts in the Hebrew Bible, but their true belief in their claim is not always justifi d as knowledge.Footnote 10 David Carr’s indictment is apropos: “In conclusion, much of the superstructure of past and present theories regarding the growth of the Bible is undermined by problematic or nonexistent arguments regarding the direction of dependence. Moreover, as these claims of intertextual dependence proliferate, the implausibility of the overall result expands exponentially.”Footnote 11 Of particular interest to us in this essay is the claim that Job relates inner-biblically to the sacred texts relating to Israel’s priesthood and cultic sacrifice. In Job 12:19, the sole and terse reference to “priests” (כהנים) in the book, Job decries God’s removal of priests, which contributes to the chaotic society surrounding Job.Footnote 12 Of course, this verse offers no evidence that it refers to priests in the Aaronic tradition, so one is forced to move on to the cultic echoes in Job’s narrative framework. Samuel Balentine concludes that “priestly imagery that provides Job’s profile in the Prologue and Epilogue is oblique and elusive,”Footnote 13 but has also claimed that, in addition to the inclusion of burnt offerings (עלה) in Job 1:5 and 42:8, several features in the portrayal of Job suggest that the book aims at questioning the priestly system of the Torah. In particular, the characterization of Job as “blameless” (תם) brings to mind the prerequisite of sacrificial animals as “unblemished” (תמים, Lev 22:19, 21; Num 19:2; Ezek 43:22–23), and by the lexical correspondence of ׁשחין (Job 2:7; Lev 13:18–20, 23), he compares Job’s disease and restoration to the skin disease instructions in Leviticus 13–14.Footnote 14 On the whole, Balentine perceives in the Joban narrative a “challenge to the priestly system of rituals.”Footnote 15 His reflections on Job’s priestly profile and the implied critique of the Torah’s priestly system are thought- provoking, but the textual evidence he presents is scant.Footnote 16

JiSeong James Kwon takes another path forward. He sees the linguistic commonalities as evidence that the scribes who composed Job and those who composed the Priestly and Holiness writings in the Pentateuch had all been enculturated in the rhetorical and lexical idiom of Jerusalem’s temple school.Footnote 17 From separate perspectives, the authors of Job and Leviticus had studied and drew freely from a shared scribal tradition. In ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and Israel, the evidence points to a long-standing, common practice of enculturating the literate elite by pushing them toward oral and written mastery of their culture’s textual tradition, including seminal works like the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Instruction of Kheti, Homer, and core texts of the Jewish Bible.Footnote 18 So also, the narrative artistry of LeviticusFootnote 19 and of the prologue-epilogue of Job is a witness to scribes who would have approached cognitive mastery of Israel’s revered corpus through rigorous recitation and memorization.Footnote 20 With this scribal framework in view, one could explain away any cultic interconnections between Leviticus and Job as arising from Jerusalem’s institution of temple scribes.Footnote 21

Defining the Relationship between Job 1–2 and Leviticus 8–10

As one appreciates ancient scribal culture and discounts “problematic or nonexistent arguments regarding the direction of dependence,”Footnote 22 one must not throw out the possibility that Job relates intertextually to salient texts in the Hebrew Scriptures. In this essay, we will argue that the scribes who composed the saga of Job 1–2 allude to the honored Torah story of Leviticus 8–10. Before contemplating the direction of influence between these stories, the evidence for literary reuse in one direction or the other can be seen in a cluster of shared lexemes and a common plot sequence: Aaron sacrifices to Yhwh for the possible sin of himself and of his sons, the oldest of whom are then killed (Lev 9:8–10:2), even as Job sacrifices to Yhwh for the possible sins of his sons and daughters, who are then killed (Job 1:4–5, 13–19).

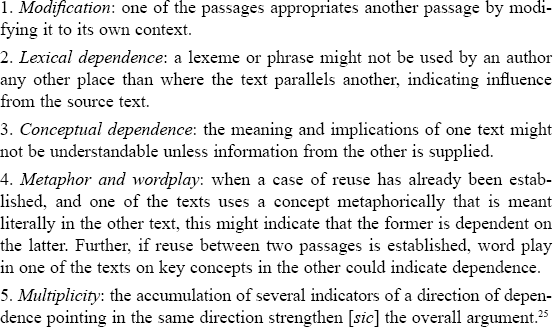

Having touched upon scribal culture, three additional terms should be defined in our methodology: allusion, direction of dependence, and visual versus memorized reuse. First, inner-biblical allusion is probably the best descriptor for Job’s reuse of Leviticus 8–10. On a spectrum from more to less knowable, Stead classifies an intertext as a genetic relationship between two texts ranging from citation → quotation → allusion → echo → trace, with citation reusing the most and trace reusing the fewest identifiable shared elements.Footnote 23 Job never cites or quotes Lev 8–10, but the critical mass of identifiable shared terms and phrases, discussed below, moves us beyond trace and echo to allusion.Footnote 24 Second, in claiming an allusion, we must provide the evidence for the direction of literary influence from the source text to the alluding text. In his clear synthesis, Bergland offers nine indicators for the direction of dependence, five of which are apropos to our study:

Figure 1

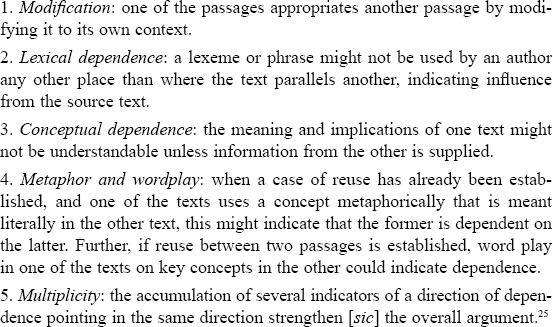

Third, ancient scribes consulted source texts visually, but more customarily pulled source texts from memory and integrated them fluidly into their new compositions. From memory a scribe could either quote a source identically or adapt it at will, often making it difficult for us to distinguish memorized and visual reuse. In fact, all the indicators for the direction of dependence noted above can also characterize memorized reuse. Even so, there are some special marks of memorized reuse that might also be evident in our case study:

Figure 2

In sum, the textual data presented below indicate that the scribe of Job’s prologue, through the voice of the implied narrator, alludes to Leviticus 8–10, but whether the allusion was constructed from memory or visual consultation remains an open question.

How Job’s Prologue Alludes to the Priestly Inauguration Story

Leviticus 8–10 and Job 1–2 share the same combination of lexemes in a coherent storyline: sanctifying (קדׁש factitive piel), sacrificing of burnt offerings (עלה), blessing (ברך), mentioning drinking wine (יין), and narrating the sudden death of some or all of the protagonist’s children (מות wayyiqtol third person pl.) by means of natural elements (“fire”/“wind”) that issue from the supernatural (יהוה מלפני/יהוה פני מעם). This combination of lexemes within the shared sequence of intermediary sacrificial performance followed by the death of the protagonist’s offspring indicates a genetic or intertextual relationship. This begs the question that Carr and others rightly would raise: Does Job reuse Leviticus or does Leviticus reuse Job? The directionality indicators presented in the body of this essay suggest that Job alludes to Leviticus and not vice versa. It is essential to note that Job’s cult is presented narratively as neither Israelite (Aaronic) nor Judahite nor Yehudite (1:1), but as Yahwistic, that is, the narrator presumes that Job’s cultic devotion to the deity Yhwh (יהוה) was in adequate continuity with the cultic expectations of Yhwh of Israel, Judah, and Yehud.Footnote 27 Consequently, the narrator’s representation of one non-Israelite Job as a cultic devotee of Yhwh by name authorizes, even orients, interpreters to compare Job’s cultic worldview with that of Moses and Aaron.

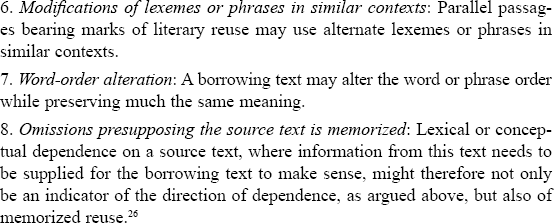

Now let us examine the lexemes shared by these two narratives. First, Moses places Aaron and his sons, and Job places his sons and daughters, into a holy state, expressed in Hebrew through the factitive-resultative piel of קדׁש (Lev 8:10–12, 15, 30; Job 1:5).Footnote 28

Figure 3

The narratives are obviously different. Moses sanctifies only Aaron and his four sons,Footnote 29 whereas Job sanctifies his daughters, too, and, in the end, honors his new daughters by naming them and giving them an “inheritance among their brothers” (42:14–15).Footnote 30 In the case of Moses, the sanctifying ritual at the priestly installation of Aaron and his sons is described at length (Lev 8:7–30).Footnote 31 In the case of Job, no details are given on how the sanctification was accomplished.Footnote 32 It remains open whether a sanctifying ritual was preparatory for Job’s sacrifices—“and sanctify them [ויקדׁשם], and he would rise and offer burnt offerings [והעלה בבקר והׁשכים עלות]”Footnote 33—or he sanctified them which necessitated (resulted in) sacrifices, “and sanctify them [ויקדׁשם], so he would rise and offer burnt offerings [בבקר והׁשכים עלות והעלה].”Footnote 34 Moses’s performance constitutes a singular act, a rite de passage, while Job’s was habitual: “This is what Job always did” (Job 1:5).

While fully appreciating these differences, we see the shared factitive-resultative קדׁש as indicative of Job’s lexical dependence on Leviticus.Footnote 35 Usage of the piel of קדׁש is revealing: In contrast to the function of the piel of קדׁש as a Leitwort in the Lev 8 narrative (5x), the piel of קדׁש in Job 1:5 is an anomaly in the book of Job. Two other biblical narratives report the sanctifi ation of persons (factitive-resultative קדׁש): Moses sanctifies the people in preparation for the Sinai theophany (Exod 19:14), and Samuel sanctifies Jesse and his sons in preparation for the sacrifice (זבח) prior to David’s anointment (1 Sam 16:5).Footnote 36 However, neither mentions burnt offerings, and only in Lev 8–10 and Job 1 do some or all of the “sanctified” persons die as each narrative unfolds.Footnote 37 Here the direction of dependence indicator of modification is also relevant.Footnote 38 It is inconceivable that Leviticus’s scribes, probably based in the Temple, would develop Yhwh’s instructions to sanctify Aaron’s children from the sparse, elusive practice of the foreign protagonist, Job, but it is entirely conceivable that Hebrew scribes would cast Job’s custom as a non-Israelite modification of an already established Priestly Torah in Leviticus.

Second, both Aaron and Job offer burnt offerings (עלה). Moses and Aaron offer burnt offerings as part of a sacrificial sequence (Lev 8–9), whereas Job offers only burnt offerings (עלות, 1:5).Footnote 39 Job’s lexical dependence on Lev 8–9 is not established by עלה alone but is shown to be more likely by its contrasting frequencies in the two books.Footnote 40 The noun עלה plays a prominent role in Lev 9, occurring ten times in twenty-four verses, more often than in any other chapter in Leviticus,Footnote 41 but by contrast the forty-two-chapter book of Job is framed by its only two occurrences of עלה, initially offered by Job (עלות,1:5) and finally by Job’s friends in obedience to the divine command (42:8–9, עולה).Footnote 42

Furthermore, in both narratives the sacrifi es have an expiatory purpose. According to Lev 9:7, Aaron is explicitly commanded to sacrifice on behalf of himself and the people (העם ובעד בעדך), but the context suggests that his sons are implicitly included in the term בעדך, since they were anointed for priestly service (8:2, 6, 13, 14, etc.) and would assist their father in the sacrifices (9:9, 12, 18).Footnote 43 For Aaron’s sacrifice for himself and his sons, this entailed a burnt offering (עלה), presumably for both unknown or unidentified impurity and sin (as Lev 1:4), but also a sin offering for any exposed violations (as Lev 4:1–5:26).Footnote 44 Given that these offerings were inaugural—not a response to identified sin—the burnt and sin offerings of Lev 9:8–14 are understood to atone for offenses against God unknown to Aaron, but either known or unknown to Aaron’s sons. In any case, Aaron’s sacrifices were explicitly to “make atonement” (piel כפר). Like Aaron, Job also sacrifices burnt offerings on behalf of his children (כלם מספר), and like Aaron, Job sacrifices to maintain a clear conscience that his household honors Yhwh and does not incur Yhwh’s judgment.Footnote 45 In Job’s prologue, however, there is an obvious omission of any technical term for expiation (such as כפר or הקרב + חטאת). This omission points toward Job’s conceptual dependence on Lev 8–10.Footnote 46 That is, how Job thought his intermediary sacrifices relate to Yhwh in the narrative is unclear, but becomes clear if Job was trying to make atonement for his children, just as the esteemed Aaron did for his (Lev 8–10).Footnote 47 The expiatory purpose of Job’s offerings differs from the sacrifices of Noah (Gen 8:20) and Jacob (Gen 31:54),Footnote 48 which are often put forward as parallels to Job 1:5.Footnote 49 Instead, knowledge of Lev 1:4, 4:1–5:26, and Lev 9:8–14 sets the precedent for Job’s idea that his burnt offerings (עלות), one for each of his children, would remove offenses against God unknown to Job (אולי חטאו), but either known or unknown to Job’s children (1:5). Also, the periodic repetition (כל־הימים) suggests that Job’s עלות were aimed at expiating transgressions committed by his children inadvertently (cf. בׁשגגה in Lev 4–5), not subject to paternal reproof.Footnote 50 In light of Leviticus 8–10, Job’s burnt offerings are not merely an “obsessional manie de perfection,”Footnote 51 but the conviction that allegiance to his deity, Yhwh, demanded a relentless and precise sacrifi mediation for his children. The consecrated Aaronic priests and loyal Job alike had to “obey their instructions implicitly, and accept arbitrary punishment without complaint.”Footnote 52

Third, “blessing” (ברך) plays an important role both in Leviticus 8–10 and Job 1–2. At the climax of the inauguration of the priesthood, Aaron blesses the people in the only two verses in Leviticus that employ ברך (9:22, in 9:23 together with Moses). In the Joban prologue, prominence is given to the verb ברך by its sixfold repetition with different meanings.Footnote 53 The evidence does not verify Job’s lexical dependence on Lev 9:22–24,Footnote 54 but does point to Job’s conceptual dependence; that is, Job 1–2 cannot be appreciated without Lev 9:22–24.Footnote 55 To be specific, there appears to be a deliberate gap (Leerstelle) in Job 1:1–3 in that divine blessing for Job is expected from the narrator’s description of his well-being, but it is never stated.Footnote 56 The Satan stands alone as the one who states that Job has been blessed by Yhwh (Job 1:10), and readers must wonder if his claim is true or not. After all, the Satan (הׂשטן) means “the Adversary” (NJPS), and he is the one who cunningly interrogates Yhwh and instigates Job’s horrific pain (Job 1–2). Leviticus 9:22–24 supports the Satan’s claim, portraying a worldview in which obedient sacrifices are one of the prerequisites of Yhwh’s blessing of his people.Footnote 57 Presuming that worldview, Job’s sacrifices come into view as aimed at preventing the possible loss of his divinely blessed status. Both Aaron’s and Job’s offerings, besides expiating sins that are unknown to them, are understood as supporting Yhwh’s blessing. Even as the narrator in the Moses story makes clear that it is Yhwh who blesses his covenant people (Lev 9:22–24; Num 6:24–27),Footnote 58 the narrator of Job’s epilogue makes clear that Yhwh had indeed blessed Job in the first half of his life and even more in the second (Job 42:12).

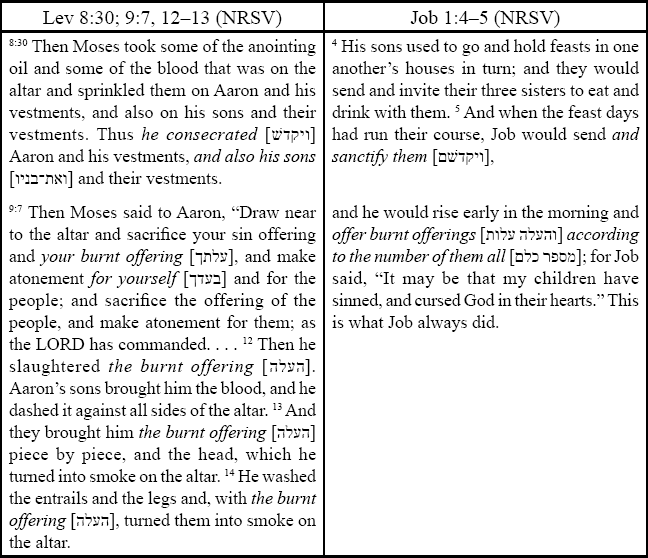

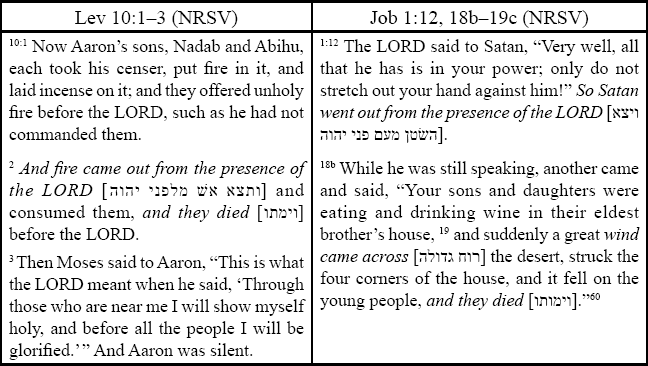

Fourth, the narrators of each story reveal “the presence of Yhwh” (יהוה פני[ל]) as the point of origin from which (מן/מעם) issues a natural element that causes the death of the protagonists’ children.Footnote 59

Figure 4

This similarity is significant since, on the one hand, the locution “going out from the presence of Yhwh” (יצא → מן → פנים → יהוה)—shared by Lev 10:2 and Job 1:12 (and 2:7)—is rare in the Hebrew Bible,Footnote 61 and, on the other hand, in both stories natural elements are employed by the supernatural to bring about the death of the father’s progeny. In addition, both stories are set in the desert (סיני במדבר, Lev 7:38; המדבר, Job 1:19), and the wayyiqtol, “and they died,” narrates the death of the fathers’ children (וימתו, Lev 10:2; וימותו, Job 1:19). This distinctive collection of shared lexemes and the shared convictions suggest a genetic link between Lev 10:1–3 and Job 1:12, 18b–19c, but do not reveal the direction of literary influence.Footnote 62 For that, other intertexts are determinative.

In Leviticus, the lethal element is “fire” (אׁש), which inverts Yhwh’s endorsing fire (אׁש, 9:24) and subverts Nadab and Abihu’s strange fire (זרה אׁש, 10:1). The verbal correspondence between Lev 9:24, where the fire emanating from the divine presence devours the offerings, and 10:2, where the fire from the same source devours Nadab and Abihu, is striking,Footnote 63 and sharpens the contrast between the legitimate sacrifices reported in Leviticus 9 and the illegitimate offering of Aaron’s oldest sons in 10:1. It underlines that the death of Aaron’s children originated directly from a divine verdict. In Job, instead, the divine origin of the calamity that causes the death of Job’s children is blurred, as it is the Satan, not the “great wind” (גדולה רוח, Job 1:19) that “went out from the presence of Yhwh” (1:12). With that said, the stories of Nadab and Abihu and Job share the important conviction that the divine presence cannot be conjured. Many biblical interpreters have puzzled over the nature of the transgression committed by Nadab and Abihu,Footnote 64 but Gary Anderson has cogently argued that the elusiveness of their infraction is actually the intentional way the Priestly authors underscore that the divine presence cannot be conjured magically by performing some legal or ritual formula.Footnote 65 In its present canonical position within the Writings after the Torah, the story and speeches of Job can be seen as an extended illustration of that strong Priestly conviction.

At the same time, the narrator’s relative clause at the end of Lev 10:1 makes it clear that Nadab and Abihu transgressed their divine orders (אתם צוה לא אׁשר “which he had not commanded them”),Footnote 66 and by this clause their death is justified by the narrator. This reveals a contrast between the rhetorical power of each narrative: the death of Nadab and Abihu (Lev 10:1–3) reinforces the authority of Yhwh’s sacrificial regulations (Lev 1–9),Footnote 67 whereas the death of Job’s children raises questions about the efficacy of the sacrificial regulations Job had adopted (Job 1:4–5, 18–19). There is also a contrast between the characters’ reactions to the death of the children. In Leviticus, Yhwh pronounces the theological reason for their death, while Aaron remains silent (10:3); whereas in Job, Yhwh remains silent, while Job pronounces the theological reason for their death, “Yhwh has given, Yhwh has taken away” (Job 1:21).

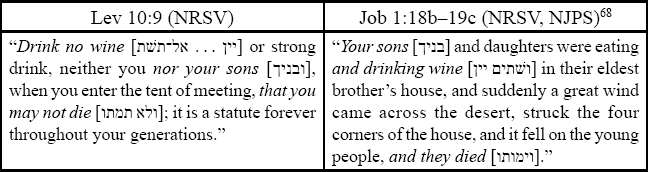

Fifth, both narrators juxtapose drinking wine with death.

Figure 5

The divine blessing of grapes and wine in the land is assumed elsewhere in Leviticus (23:13; 26:5), but, by contrast, the prohibition of Lev 10:9 on the heels of 10:1–3 may insinuate that Nadab and Abihu were influenced negatively by alcohol when they enacted their strange fi ritual, which Yhwh “had not commanded them.”Footnote 69 Similarly, the blessing of eating and drinking wine in Job 1:13, 18 is tainted by Job’s fear: “ ‘It may be that my children have sinned and cursed God in their hearts’ ” (בלבבם אלהים וברכו בני חטאו אולי, 1:5).Footnote 70 Bildad the Shuhite reasserts Job’s concern as an indicting conditional: “ ‘If your children sinned against him, he delivered them into the hand of their transgression’ ” (Job 8:4; cf. 5:3–4; 21:19–20; 27:14). The implication for both Job and Aaron is that their children may have been under the influence of alcohol before their death.

To be clear, the lexical dependence of Job 1:18b–19c on Lev 10:9 cannot be validated, but three observations intimate inner-biblical reuse and at least leave open the possibility that the scribe of Job 1:18–19 alludes to Lev 10:9.Footnote 71 First, the prohibition of wine (and other alcoholic drinks) is infrequent in the Torah, occurring only in Lev 10:9 and Num 6:3 (for Nazirites).Footnote 72 As with the Lev 10:9 prohibition, a negative aura surrounds the eating and wine-drinking of Job’s children since Job is concerned they may have cursed God in their hearts (Job 1:5, 13, 18). Second, although the motif of eating and drinking recurs often in biblical narratives as an expression of festive joy, it is highly uncommon that wine is explicitly mentioned in this context, as is the case in Job 1:13, 18.Footnote 73 Third, there is only one other episode in the Pentateuch in which Nadab and Abihu are mentioned, Exod 24:9–11. By invitation in Exod 24:1, Moses, Aaron, seventy elders, Nadab and Abihu “ate and drank” (ויׂשתו ויאכלו, 24:11) in God’s presence on Sinai; also by invitation, Job’s daughters came “to eat and drink” (ולׁשתות לאכל, Job 1:4) with their brothers.Footnote 74 The mention of Nadab and Abihu by name and their nearness to God links Exod 24 with their dramatic death in Lev 10:1–3, 9.Footnote 75 Likewise, Job’s sons and daughters eat and drink wine and die a dramatic death (Job 1:4–5, 18–19),Footnote 76 but where is God’s presence in the festivities and death of Job’s children? It is intriguing to us that in his closing soliloquy, Job places the presence of God and of his children in synthetic parallelism, “when the Almighty was still with me, when my children were around me” (Job 29:5 NRSV).

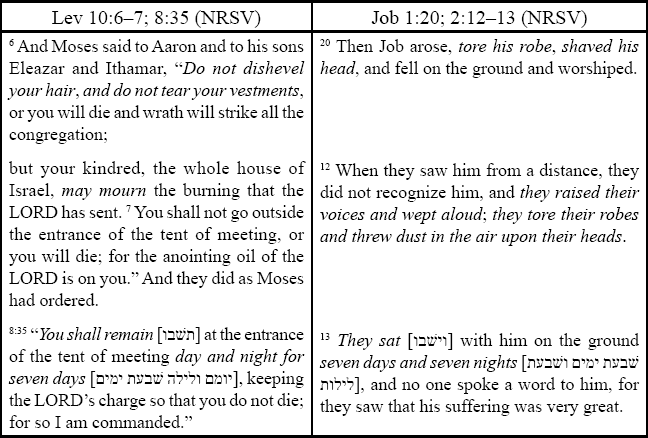

Reading Job 1–2 against the backdrop of Lev 8–10 illuminates a contrast between the mourning rites of Aaron and of Job at the death of their children.

Figure 6

The thematic and lemmatic similarities could be an echo,Footnote 77 maybe specifically an echo resulting from memorized reuse,Footnote 78 but the direction of influence cannot be demonstrated from these texts alone. Rather, because of the other surrounding evidence for an allusion outside these verses, one might also compare Aaron’s customs with Job’s. Aaron and his surviving sons are prohibited from performing conventional mourning rites because Yhwh’s anointing oil was on them (Lev 10:6–7; the high priest in 21:10; cf. Ezek 24:16–18), whereas Job had no such constraint (Job 1:20).Footnote 79 The priests were not to shave bald spots on their heads or shave off the edges of their beards (Lev 21:5; cf. 19:27), but Job, not a vocational priest, shaves his head in grief (Job 1:20), and then at the culmination of his affliction, he mourns ritually with his friends (2:12–13).Footnote 80 The freshly anointed priests had to remain together day and night for seven days in the tent of meeting (8:33–35; see Exod 29:30), and similarly, Job’s friends remained seven days and seven nights “with him” (אתו, 2:13). Job’s friends show him sympathy and sit with him in silence (2:13), which sharply contrasts Moses’s lack of sympathy for Aaron’s family (esp. 10:16) and Moses’s string of verbal directives to Aaron (10:3–5, 6–7, 12–15). Perhaps the most salient contrast is Yhwh’s silence toward Job, broken only after the aggravating dialogues (Job 38:1), whereas Yhwh speaks immediately and directly to Aaron and his remaining sons to give them their vital priestly vocation (10:8–11).

Implications for Interpreting Job

Job’s probable allusions to the priestly inauguration story in Leviticus 8–10 expose certain ambiguities in Job’s prologue, speeches, and epilogue. We begin with Job’s dense prologue. First, hearing its resonances with Leviticus 8–10 leads us to consider the only other short story in Leviticus, which involves the blasphemy and death of the son of Shelomith in 24:10–23. If the standard of Leviticus 24 were upheld, the transgressions of Job’s children would demand their death without any possibility of expiation, since “blessing God” (בלבבם אלהים וברכו, Job 1:5) is understood as a euphemism for a blasphemous utterance (tantamount to ארר, קלל, נקב).Footnote 81 Most commentators, however, interpret the phrase merely as “the extreme to which they may have descended without anyone else being aware.”Footnote 82 Still, it remains unclear whether Job’s vicarious sacrifice would be effective without the offenders’ remorse and confession.Footnote 83 Second, Job’s sacrifice seems questionable because it is aimed at expiating transgressions only thought of (בלבבם), but not executed, or possibly not committed at all (אולי).Footnote 84 At the same time, however, Job, in contrast to Aaron (Lev 9:7), does not immolate for himself.Footnote 85 Therefore, when read against the cultic expectations of Leviticus 8–10 and 24, the father Job in 1:5 either does too much—by expiating for sins not committed or, if blasphemy was uttered, by offering atoning sacrifices in vain—or too little—by not atoning for himself or admonishing his children toward remorse and confession.Footnote 86 These concluding reflections on Job 1:5 are based on knowledge gaps in the story, which generate curiosity for readers.Footnote 87 The language and theology of Leviticus 8–10 expose these gaps and call attention to the ambiguities of Job’s cultic practice that sit uncomfortably next to his unassailable integrity and devotion to Yhwh (1:1, 5, 8, 20–22).

In the speeches of Job 3–41, it has often been noted that the friends do not admonish Job to resort to sacrifi offerings, nor do they or Job use cultic vocabulary. However, when Bildad in his first speech mentions the possible sins of Job’s children engendering God’s retribution (8:4), this recalls Job 1:5, 19 and reminds us of God’s retribution against the sins of Aaron’s sons (Lev 10:1–3). From this perspective, Bildad’s subsequent advice—“if you seek God and seek the favor of the Almighty, if you become pure and upright” (8:5–6)—demands, at least in part, Job’s observance of the sacrificial cult.Footnote 88 His assurance that “God will not reject one who is blameless [תם]” (v. 20) may also bring to mind the “unblemished” (תמים) state of sacrificial animals acceptable to God. It should be said that this literary context for Bildad’s speech is conjectural and comes into view only in a synchronic reading.

Finally, in Job’s epilogue, Yhwh commands Job’s friends to sacrifice burnt offerings for themselves and tells Job to intercede on their behalf (42:8).Footnote 89 If one infers that Job was healed from his skin disease (42:10, 17), although the narrator is strangely silent about this,Footnote 90 this would have happened in the storyline in 42:10–17 only after 42:8. According to Lev 21:23, Israel’s priests with “an itching disease or scabs” (ילפת או גרב [v. 20]) were banned from offering Yhwh’s sacrifices. This could be part of the reason that Job’s friends offer their own burnt offerings, whereas Job is commanded to intercede only: a physically whole Job offers burnt offerings in 1:5 for the potential sins of his children (1:5), but a skin-diseased Job cannot approach Yhwh to offer burnt offerings for the sins of his friends (42:8). In any case, Job does not repent because of known sin (42:6; cf. 1:1, 8; 2:3; 31:1–40),Footnote 91 which correlates with the detail that, “These friends need repentance and expiatory sacrifices, but Job requires neither (42:7–8).”Footnote 92 However, the location of 42:7–9 as part of the epilogue, against the opening scenes in Job 1–2 and against Israel’s cultic tradition (à la Lev 8–10), creates an ambivalence.Footnote 93 In contrast to the unmistakable divine responses to the offerings of Aaron (Lev 9:22–24, positive) and Nadab and Abihu (10:1–3, negative), there is no known divine response to Job’s burnt offerings for his sons and daughters. Divine silence is followed by tragic death (Job 1:19), and Job loses whatever semblance of control he thought he was maintaining.Footnote 94 The reader’s memory of the death of Job’s sanctified children (1:5, 19) raises suspicion about what will ensue from the sacrifices of Job’s friends and his intercession for them (42:8). The result of their actions is told by the narrator: “And Yhwh lifted Job’s face” (איוב את־פני יהוה ויׂשא, 42:9c).Footnote 95 Whatever this means,Footnote 96 it cannot mean that Yhwh’s cult is now, at last, a hermetically sealed system that one can employ to control the divine and one’s own life.Footnote 97 No longer could Job or his friends trust in their integrity and cultic devotion to Yhwh to insulate themselves from economic crisis, disease, the death of their children, or even the deafening silence of Yhwh.

Conclusion

In this article, we have identified in Leviticus 8–10 and Job 1–2 a shared narrative sequence and a dense collection of key identical lexemes. We have argued that the textual data is adequate to conclude that the scribes of the book of Job, enculturated by memorizing and producing Judah’s sacred texts like the Torah,Footnote 98 have infused Job’s story with allusions to the priestly inauguration story of Lev 8–10. In short, reading Job’s prologue after Leviticus illuminates the absurdity of the death of Job’s children in the face of Job’s devotion to Yhwh through intermediary sacrificial performance. More generally, the sudden death of Job’s children after Job’s sacrifices on their behalf challenges the cultic tradition of Israel as a whole. While at first glance it seems that the book of Job is situated exclusively in the realm of Wisdom, questioning the retribution principle on which the books of Psalms and Proverbs are largely based, the experiences of Job, a loyal devotee of Yhwh, oppose a mechanistic understanding of the Priestly worldview of the Pentateuch.Footnote 99 Most notably, the death of Job’s children for whom he so faithfully sacrificed burnt offerings incurably wounds human trust in the reliability of any priestly cult of Yhwh. Job’s burnt offerings for his children do not avert their death (1:5, 18–19), as Aaron’s do (Lev 9:24–25). Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, die for their transgression (Lev 10:1–3), whereas the reason Job’s sons and daughters die eludes Job entirely and cannot be explained by the Priestly worldview of sin, divine retribution and sacrifice (Job 1:6–19; 2:1–7; 38:1–41:34). The story of Job, of course, is not alone in its critique. In fact, the Priestly scribes already inserted this criticism into their writings: The ambiguity of Nadab and Abihu’s transgression illustrated that mastering cultic rituals will never enable the priests to conjure Yhwh’s presence.Footnote 100 Neither would Job’s cultic mastery (1:5) or cries of lament (3:1–31:40*) empower him to conjure Yhwh’s presence.

On one level, Job illustrates how “priests who stand inside the rituals that bind a fragile world to a holy God are most attuned to their tasks when they know themselves vulnerable to the wounds of this world.”Footnote 101 However, human reliance on these rituals to always “bind a fragile world to a holy God” is undermined by the book of Job, especially in contrast to the reliable system presented in Leviticus 8–10. Consequently, in his ongoing priestly mediation for those who transgress Yhwh (42:8), Job remains vulnerable not merely to suffering, but to a cultic system that fails to explain or terminate his suffering. Through the barrage of speeches, the narrator displays Job as a full character with a complex set of emotions that bleed into the epilogue (Job 3:1–42:6).Footnote 102 Even as Job’s blessings invert his sufferings (42:10–17), his “restoration rings hollow.”Footnote 103 For Job to be a human, which the narrator insists, Job must have been indelibly marked by his former agony (as 2:12–42:6), and anyone who has tasted life’s cruelty imagines him carrying the painful memories and scars of his recent past. He has learned what it feels like to “fear God with no effect” (1:9, החנם).Footnote 104 In contrast to effectual Priestly theology in which cultic intermediaries influence God’s response by their ritual obedience (Lev 9:22–24) or transgression (Lev 10:1–3),Footnote 105 Job, also an intermediary (Job 1:5; 42:8), faithfully offers sacrifices that neither protect his children nor elicit any revelation of divine acceptance (1:5),Footnote 106 but he never abandons his integrity and devotion to Yhwh. Job’s cultic efforts add another layer to his sense of futility: “Will I be condemned? Why then should I waste effort” (9:29).Footnote 107 But it is precisely these feelings of futility that deepen Job’s longing for the God who “does great things that we cannot understand” (37:5b).Footnote 108