Article contents

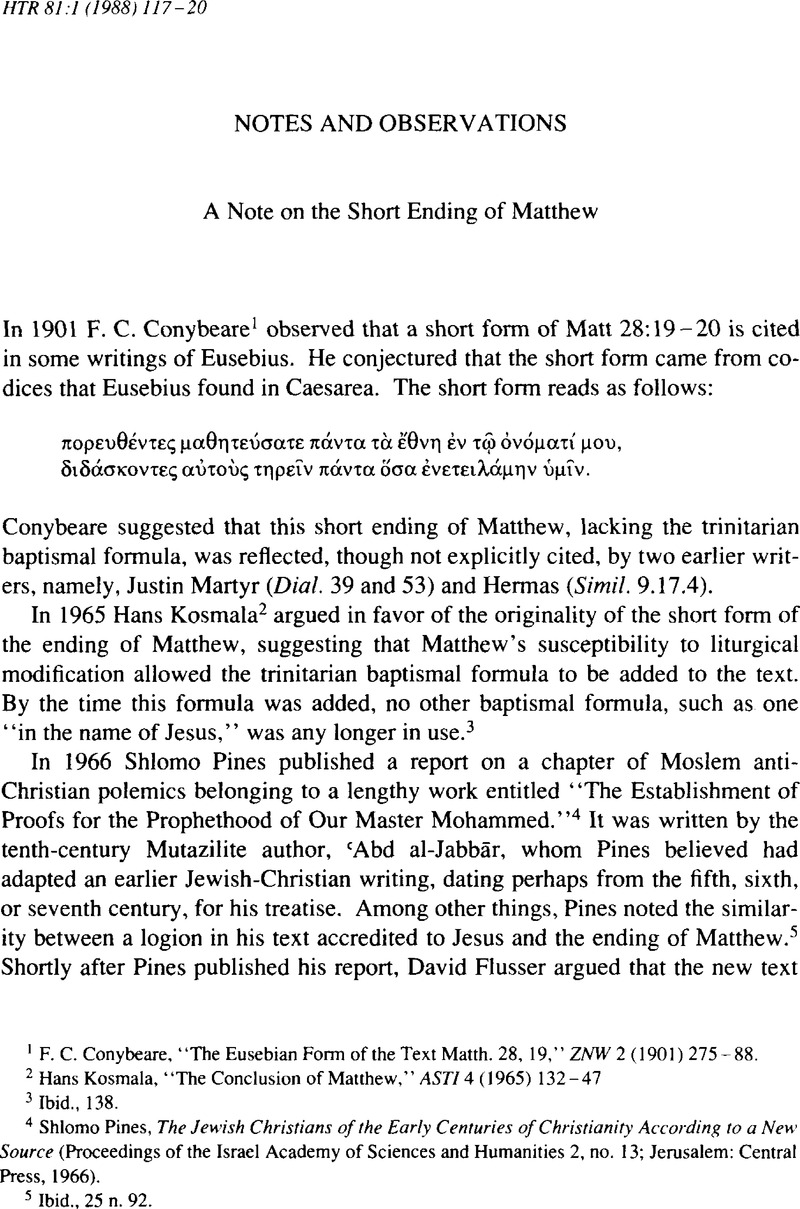

A Note on the Short Ending of Matthew

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Notes and Observations

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © President and Fellows of Harvard College 1988

References

1 Conybeare, F. C., “The Eusebian Form of the Text Matth. 28, 19,” ZNW 2 (1901) 275–88.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 Kosmala, Hans, “The Conclusion of Matthew,” ASTI 4 (1965) 132–47Google Scholar

3 Ibid., 138.

4 Pines, Shlomo, The Jewish Christians of the Early Centuries of Christianity According to a New Source (Proceedings of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities 2, no. 13; Jerusalem: Central Press, 1966).Google Scholar

5 Ibid., 25 n. 92.

6 Flusser, David, “The Conclusion of Matthew in a New Jewish Christian Source,” ASTI 5 (1967) 110–20.Google Scholar

7 In opposition to Pines's view see Stern, S. M., “New Light on Judaeo-Christianity,” Encounter 28 (1967) 53–57Google Scholar; idem, “Quotations from Apocryphal Gospels in 'Abd al-Jabbār,” JTS n.s. 18 (1967) 34–57Google Scholar; idem, “'Abd al-Jabbār's Account of How Christ's Religion was Falsified by the Adoption of Roman Customs,” JTS n.s. 19 (1968) 128–85.Google Scholar See also Maier, Johann, Jesus von Nazareth in der talmudischen Überlieferung (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1978) 47Google Scholar n. 73. For a more balanced view see Bammel, Ernst, “Excerpts from a New Gospel?” NovT 10 (1968) 1–9.Google Scholar Bammel argued that ‘Abd al-Jabbār made use of Toledoth Jeshu tradition that was influenced by canonical and extracanonical stories.

8 See Pines, Jewish Christians, 6.

9 For discussions of various editions of the Even Bohan issued by Shem-Tob see Marx, Alexander, “The Polemical Manuscripts in the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America,” in Studies in Jewish Bibliography and Related Subjects in Memory of Abraham Solomon Freidus (1867–1923) (New York: Alexander Kohut Memorial Foundation, 1929) 247–78Google Scholar; Horbury, W., “The Revision of Shem Tob Ibn Shaprut's Even Bohan,” Sefarad 43 (1983) 221–37.Google Scholar

I have published a critical edition of this text along with an English translation and a detailed analysis. See Howard, George, The Gospel of Matthew According to a Primitive Hebrew Text (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1987).Google Scholar

10 See the critical edition mentioned above in n. 9.

11 George Howard, “A Primitive Hebew Gospel of Matthew and the Tol'doth Yeshu,” in NTS (forthcoming).

12 Some of the marks of Hebrew composition are puns, word connections, and alliteration. These are presented in the critical edition noted above. Some are recorded in Howard, George, “Was the Gospel of Matthew Originally Written in Hebrew?” Bible Review 2 (1986) 14–25.Google Scholar See also idem, “Shem-Tob's Hebrew Matthew,” in Proceedings of the Ninth World Congress of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem: World Union of Jewish Studies, 1986) 223–30.Google Scholar

13 Beare remarks: “The harshness of the saying of Jesus … still puzzles the Christian reader, who finds it impossible to imagine Jesus addressing a distraught mother in such terms. … Dare we see in all this a reflection of the reluctance with which the primitive Church embarked upon the Gentile mission?” Beare, Francis W., The Earliest Records of Jesus (Nashville: Abingdon, 1962) 132–33.Google Scholar

14 Hare and Harrington argued that πάντα τ ἔθνη means Gentiles only and does not include Israel. Douglas Hare, R. A. and Harrington, Daniel J., “‘Make Disciples of All the Gentiles’ (Matthew 28:19),” CBQ 37 (1975) 359–69.Google Scholar Against this see Meier, John P., “Nations or Gentiles in Matthew 28:19?” CBQ 39 (1977) 94–102.Google Scholar Cf. Brown, Schuyler, “The Two-fold, Representation of the Mission in Matthew's Gospel,” StTh 31 (1977) 21–32.Google Scholar

- 5

- Cited by