Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

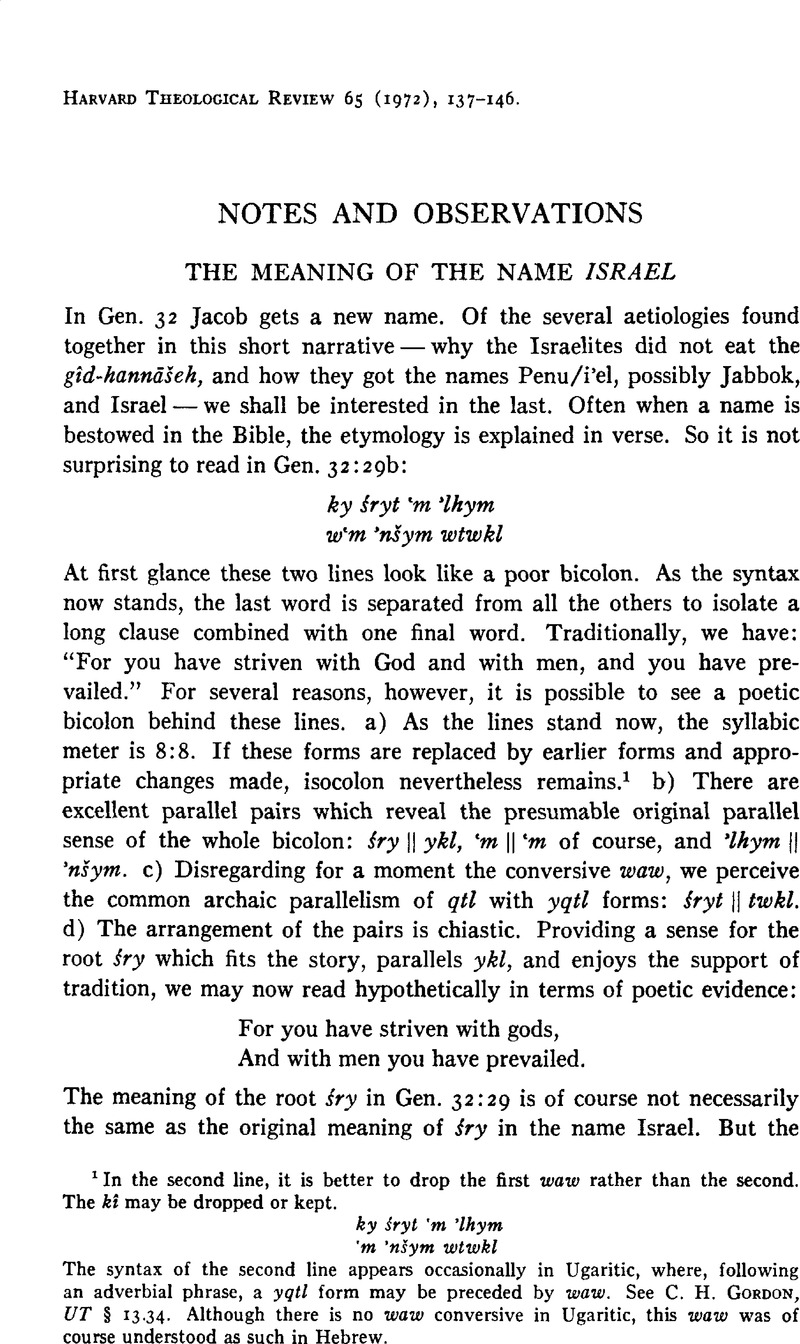

1 In the second line, it is better to drop the first waw rather than the second. The ki may be dropped or kept.

The syntax of the second line appears occasionally in Ugaritic, where, following an adverbial phrase, a yqtl form may be preceded by waw. See C. H. Gordon, UT § 13.34. Although there is no waw conversive in Ugaritic, this waw was of course understood as such in Hebrew.

2 Albright, W. F., The Names “Israel” and “Judah” with an Excursus on the Etymology of Tôdâh and Tôrâh, JBL 46, 151–85Google Scholar, especially 156–57.

3 For the combined notions of correspondence, buying, and selling, compare Aramaic zbn, “to buy” (D = “to sell”), with Akkadian zibānītum, “scales.”

4 Albright, 160.

5 Albright, 167–68.

6 Cf. the rare I form meaning of šarâ (“to correspond”), “to shine”; Albright, 156, 157.

7 Cf. Albright, 168.

8 Arabic malaka means “to own, possess.” This meaning would appear, however, to be secondary from the basic meaning in Akkadian. In Arabic the verb is probably denominative from a borrowed noun meaning “ruler.” The verse māliki yawmi-ddīni from the opening Sūra of the Qurʼān suggests a sense of judging in the root, perhaps complementary to the ordinary translation “master” or “owner.”

9 For the following discussion see the lexicons, along with F. M. Cross, The Canaanite Cuneiform Tablet from Taanach, BASOR 190, 41–46, and M. H. Pope, Marginalia to Dahood's, M.Ugaritic-Hebrew Philology, JBL 85, 455–66.Google Scholar

10 Cross, 45.

11 In a difficult text Šapšu apparently casts roles among the company of El after the defeat of Mot. The rapiʼūma and ʼilāniyyūma are surely the hoi epi Kronou, the “ones of the time of Kronos (El)” mentioned by Sanchuniathon (37b, 38b–c). Although both epithets are to be taken as referring to “divinities,” being equivalent to the ʼēlōhîm in the council of El in Ps. 82 or the benê ʼēlîm in Ps. 29:1, this pair may allude to a parallelism similar to the pair gods ‖ men in Gen. 32. Albright, (Archaeology and the Religion of Israel [1942], 218)Google Scholar has noted the shift in meaning from “hero” to “shade” exemplified by Canaanite Rephaim and Greek hērōs. Further on I will point to the significance of this congruence with Gen. 32.

12 So Pope, 465–66.

13 So Cross, who suggests the meaning “patriarch,” that is, ruler of the family or clan. Cross, 45, footnote 24. In this whole connection the epithet of Zeus is interesting: patēr andrōn te theōn te (Od. 1:28, etc.). ḥtk occurs now in Ugaritica V, 2.V0.8,10, but the interpretation is still unsure. The general semantic development discussed here occurs also in Indo-European languages, for example with Greek krinō. German entscheiden is formed from scheiden, “to separate” (cf. Greek schizō) similarly to English “decide,” which comes from Latin dēcīdō (dē-caedō) through the several intervening French forms. See also Falk, Z. W., Hebrew Legal Terms: III, JSS 14(1969), 39–44.Google Scholar

14 It is not possible to decide definitely whether the root is śry or yśr. In either case we would expect yiśreʼēl rather than yiśrāʼēl. Both the LXX and the Hexapla, however, evidence the pre-Massoretic tendency to vocalize šewâ followed by a laryngeal in names formed with a III-weak verb as –a–. The Greek transliteration is normally Israēl. In maintaining their highly consistent grammar, the Massoretes returned this a−vocalization to šewâ in all names except the two best known, Israel and Ishmael. In these, a > ā in an open pretonic syllable, as expected (in Ishmael, the aleph quiesces). See Albright, The Names …, 162–63.

If the root in Israel were yśr, we would expect the development *yaśirʼil > *yiśirʼil > *yiśreʼēl > yiśrāʼēl. A similar name would be *yabilʻam > *yibilʻam > yibeʼam, from the root y/wbl (cf. Egyptian ya-b-ra-ʻa-m). If, on the other hand, the root were śry, then *yaśriʼil > *yiśreʼil > yiśrāʼēl, like *yabni-yahū > *yibne yāhū > yibne yāhū (yibne yāh) from the root bny.

The Assyrian gentilic sir-'i-la-a-a, i.e., “the Sir'il-ite,” favors a I-y/w root, with *yas”ir- > śir-, a development attested in names such as *yabilʻam > *bilʻam > bilʻām. As Albright points out (167), for the root śry we should expect the more exact writing si-ri-'i-la-a-a. The Merneptaḩ Stele gives us no help in deciding the root.

The name Jeshurun may be a northern Israelite variant of the name Israel formed on either the qatul or qutul pattern of yśr. Thus we would have *yašurān > *yešōrōn > *yešūrūn. The form would be equivalent to zebūlūn < *zubul-ān, following the expected Phoenician developments *ś/š and *ō > ū.

The sense which is here proposed for the name Israel may be supported by recalling that one of the most frequently occurring roots in Israelite names is špṭ.

15 See now Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture, by ThorkildJacobsen, edited by William L. Moran (Harvard Semitic Series 21, Cambridge, 1970), 150–51, 194–95. Although the epithet šar mîsarim could be regarded as merely a proper translation of LUGAL NÍG-SI-SÁ, it does connote in stylized fashion the same promulgation involved in the name Israel.

I should also call attention to the epithet which Ya⸫dun-Lim applies to Šamaš in a dedicatory inscription from eighteenth century Mari: šāpiṭ ilī u awīlūtim (I:3). See Dossin, G., L'inscription de fondation de Iaḫdun-Lim, roi de Mari, Syria 32 (1955).CrossRefGoogle Scholar 1–28, esp. 4, 12.

16 Cf., consequently, Luke 2:52.

17 Cf. Text 4.7.49–52. Either Baal in his kingship or Mot in his defiance speaks:

ʼaḩaduya dū-yamluku ʽal ʼilīma

la-yamarriʼu ʼilīma wa-našima

dū-yašbi[ʽu] hamullāti ʼar⊡i

It is I alone who rule over gods,

(Who) fatten gods and men,

Who satisfy the multitudes of the earth.