No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

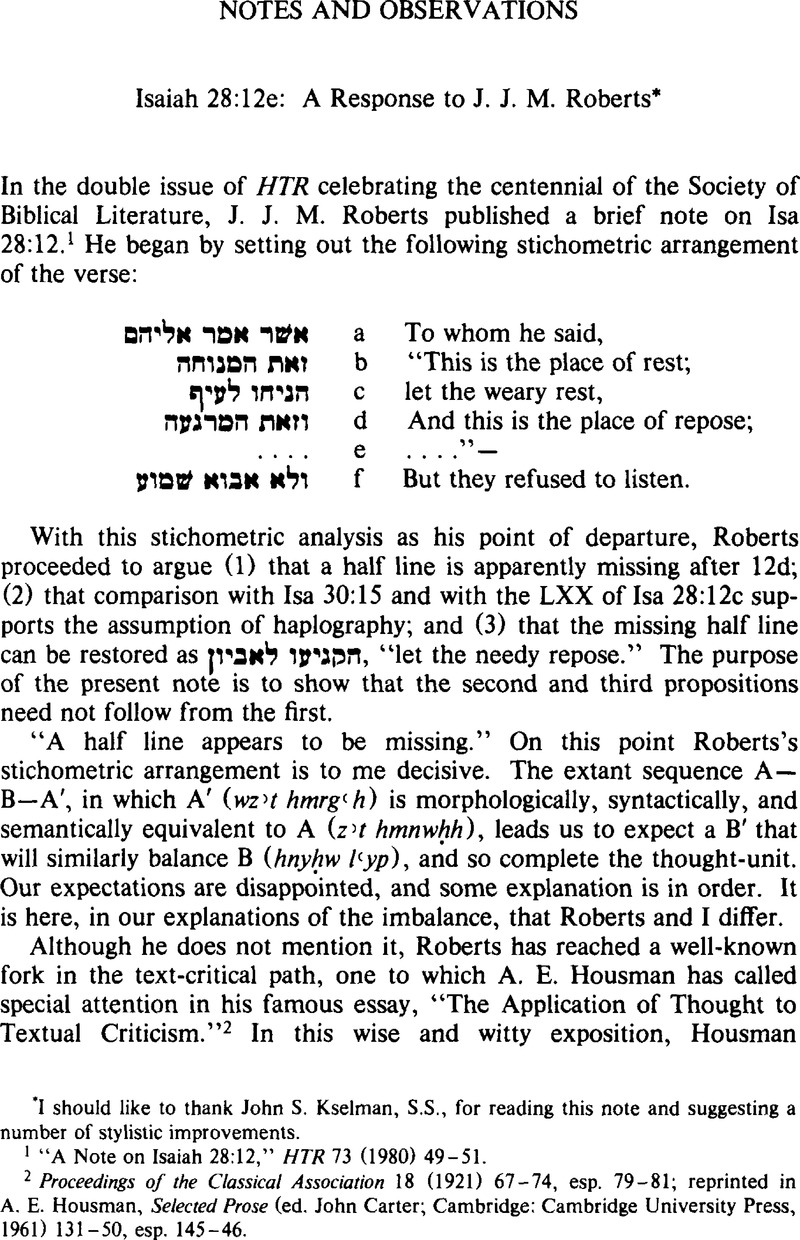

1 “A Note on Isaiah 28:12,” HTR 73 (1980) 49–51.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 Proceedings of the Classical Association 18 (1921) 67–74, esp. 79–81Google Scholar; reprinted in Housman, A. E., Selected Prose (ed. Carter, John; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961) 131–50, esp. 145–46.Google Scholar

3 Proceedings, 80–81; Selected Prose, 146.

4 Roberts seems to underestimate the value of his own literary perceptiveness when he implies that his stichometric analysis is too “subjective” to be persuasive on its own: “Of course, one could argue that this perception of a lack of symmetry is purely subjective, and that it provides no objective basis for assuming an actual haplography in the text” (49). I have two objections to this “of course,” one practical, the other theoretical. In practice, textual criticism, whether well or poorly done, is no more “objective” in procedure or results than literary or poetic criticism. To quote Housman's famous simile, “a textual critic engaged upon his business is not at all like Newton investigating the motions of the planets: he is much more like a dog hunting for fleas” (Proceedings, 68–69; Selected Prose, 132). And on the theoretical level, both “purely subjective” and “purely objective” are empty and in effect meaningless categories. On the whole question of “subjectivity” and “objectivity” in textual analysis, see the provocative (and to me persuasive) discussion in Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980) esp. 332–36.Google Scholar

5 On the minuses in the LXX Isaiah, see Ziegler, J., Untersuchungen zur Septuaginta des Buches Isaias (AtAbh 12/3; Münster: Aschendorff, 1934) 45–46.Google Scholar Note especially the following: “Der Js-Übers. fühlte sich nicht strenge an seine Vorlage gebunden und hatte auch keineswegs die Absicht, wörtlich und genau, Wort für Wort zu übersetzen; deshalb hat er … manche Sätze verkürzt und zusammengezogen” (46–47). See also the remark of Cross, F. M. (“Problems of Method in the Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible,” in O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger, ed., The Critical Study of Sacred Texts [Berkeley Religious Studies Series; Berkeley: University of California, 1979] 31–54)Google Scholar: “the Greek text of Isaiah is a notoriously bad translation, paraphrastic and unpredictable, justifying in some part past claims about the uncertainty of retroversion” (51).

6 Roberts himself (50) posits an unlikely double haplography to explain the complete loss of 28:12e, thus implicitly acknowledging that the assumed haplographies in 28:12c and 28:12e are in fact not “of precisely the same sort.”

7 “Note,” 49–50.

8 “Unverkennbar ist doch die Ähnlichkeit unsers Verses, zumal auch des Schluss satzes, in Form and Inhalt mit c. 30:15” (Das Buch Jesaia [HKAT 3/1; 2d ed.; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1902] 169).Google Scholar Other commentators—including Kaiser, O. (Isaiah 13–39: A Commentary [OTL; Philadelphia: Westminster, 1974] 246)—also compare the two verses.Google Scholar

9 In 30:15 there is no morphological parallelism between A (bšwbh wnbḥt) and A′ (bhšqṭ wbbṭḥh), and the syntactic parallelism between the two is upset by the absence of a second preposition b- in A. Between B (twšʿwn) and B′ (thyh gbwrtkm) the parallelism is only semantic.

10 The LXX translator, almost certainly influenced by 28:12, adds ⋯κοὐειν at the end of 30:15. I have found no scholar foolhardy enough to argue that the LXX addition reflects a real variant, let alone a superior reading.

11 That such near total regularity is not typical of I Isaiah may be demonstrated by comparison of 28:12 with its “closest Isaianic parallel,” 30:15 (see above n. 9). If B′ in this latter verse had been omitted by haplography from MT and all the versions, how many of us would be tempted to restore thyh gbwrtkm? Yet in 28:12 the missing fourth line was obviously intended to begin with hrgyʿw l- and to conclude with a synonym of ʿyp.

12 Isaiah 28–33: Translation with Philological Notes (BibOr 30; Rome: Biblical Institute, 1977) 23–25.Google Scholar Irwin might also have noted that this concentric construction is not confined to vs 12, but extends back into vs 11 and forward into vs 13. The close of vs 11 (ydbr ʾl hʿm hzh) is chiastically balanced by the beginning of vs 13 (whyh Ihm dbr YHWH).