Article contents

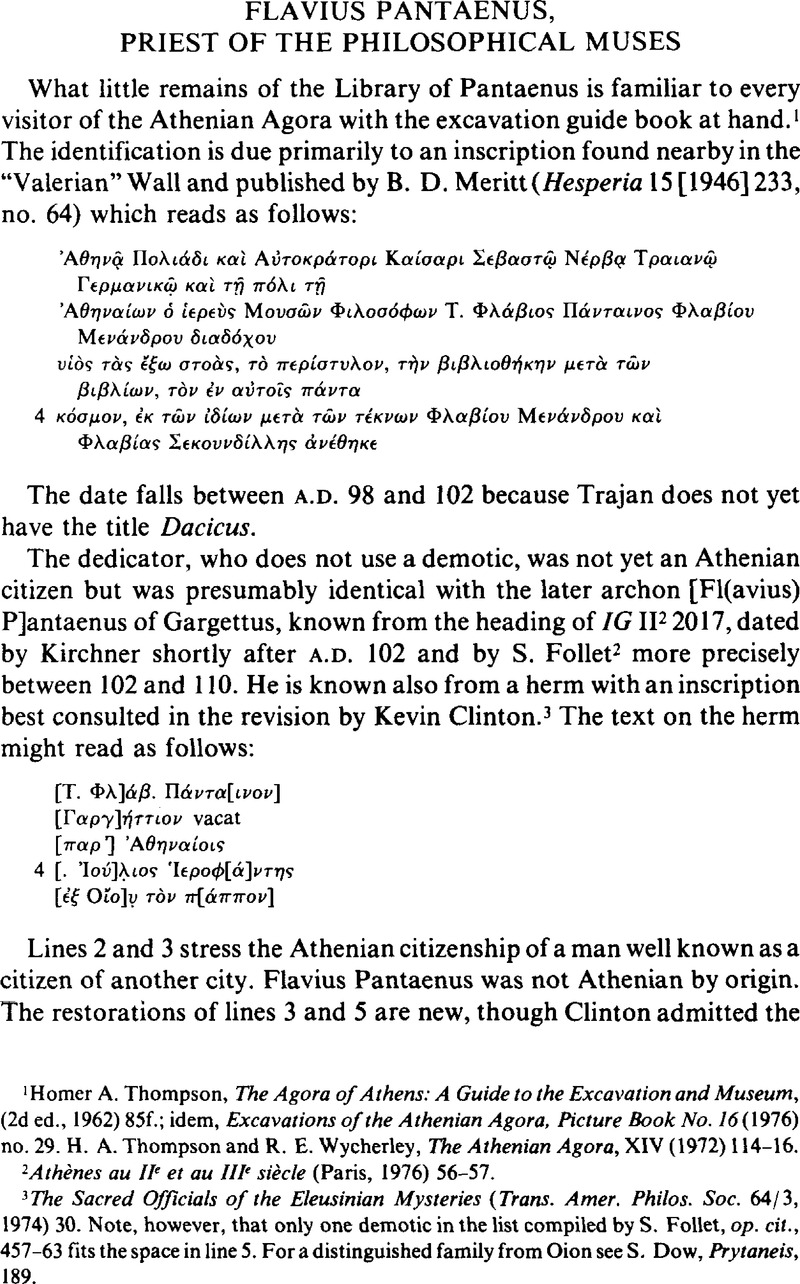

Flavius Pantaenus, Priest of the Philosophical Muses

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Notes and Observations

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © President and Fellows of Harvard College 1979

References

1 Homer A. Thompson, The Agora of Athens: A Guide to the Excavation and Museum, (2d ed., 1962) 85f.; idem, Excavations of the Athenian Agora, Picture Book No. 16 (1976) no. 29. Thompson, H. A. and Wycherley, R. E., The Athenian Agora, XIV (1972) 114–16Google Scholar.

2 Athènes au IIe et au IIIe siècle (Paris, 1976) 56–57Google Scholar.

3 The Sacred Officials of the Eleusinian Mysteries (Trans. Amer. Philos. Soc. 64/3, 1974) 30. Note, however, that only one demotic in the list compiled by Follet, S. op. cit., 457–63 fits the space in line 5. For a distinguished family from Oion see Dow, S. Prytaneis, 189.

4 See further Conomis, N. C., Hesperia 29 (1960) 418Google Scholar, and Oliver, J. H., “The Athens of Hadrian,” Les empereurs romains d’Espagne (Paris: CNRS, 1965) 125–31Google Scholar.

5 A diadochos was the head of a philosophical school in succession to Plato, Zeno, or Epicurus. The number of diadochoi at Athens is not recorded, but from inscriptions Oliver, J. H. (“The Diadochē at Athens under the Humanistic Emperors,” AJP 98 [1977] 160–78)Google Scholar inferred that there were three diadochoi, one main diadochos representing the interests and property of Platonists, Aristotelians, and eclectics, then two diadochoi for the two sects which remained aloof, the Stoics and the Epicureans.

6 It was published by Paribeni, R. and Romanelli, P., “Studii e ricerche archeologiche nell’Anatolia meridionale,” Monumenti Antichi 23 (1914) coll. 148–52Google Scholar with photograph of squeeze, and was improved by Wilhelm, A., “Neue Beiträge zur griechischen Inschriftenkunde IV,” SBWien 179/6 (1915) 62–64Google Scholar.

7 For similar datives of hommage see Veyne, P., “Les honneurs posthumes de Flavia Domitilla et les dédicaces grecques et latines,” Latomus 21 (1962) 49–98Google Scholar.

- 3

- Cited by