Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

1 Milik did not publish it with the rest of the finds from Murabbaʿat in DJD II. He passed it to Jonas Greenfield, who died in 1995 after passing it to Ada Yardeni, who in turn published t i in a thin booklet of all the readable papyri, Ṣeʾelim (Naḥal Ṣeʾelim Documents [Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Ben Gurion University in the Negev Press, 1995])Google Scholar.

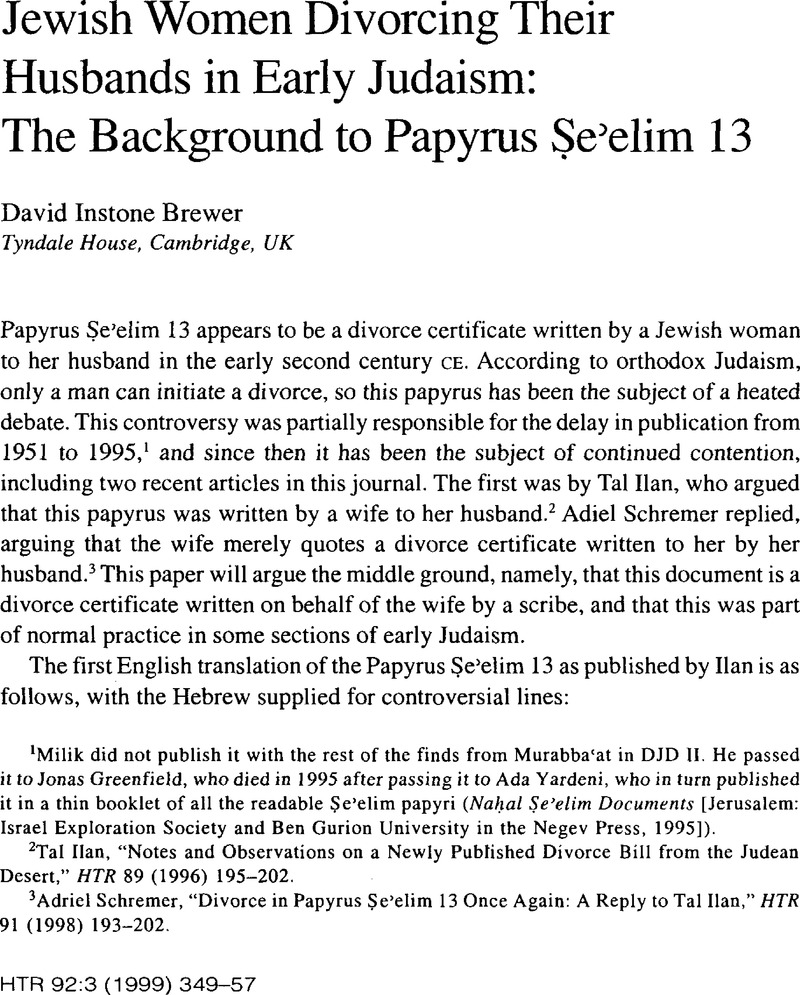

2 Ilan, Tal, “Notes and Observations on a Newly Published Divorce Bill from the Judean Desert,” HTR 89 (1996) 195–202.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

3 Schremer, Adriel, “Divorce in Papyrus Ṣeʾelim 13 Once Again: A Reply to Tal Ilan,” HTR 91 (1998) 193–202.Google Scholar

4 Such receipts are referred to in early rabbinic literature (for example, m.Ketub. 9.9). Evidence for such receipts is summarized well in , Han's paper (“Notes and Observations,” 197).Google Scholar See also Cotton, Hannah, “A Cancelled Marriage Contract from the Judaean Desert (XHev/Se Gr.2),” JRomS 84 (1994) 64–86, esp. 66Google Scholar.

5 This was the opinion of Jonas C. Greenfield and Ada Yardeni, as summarized by Ilan.

6 See , Schremer, “Divorce Once Again,” 196–99Google Scholar.

7 Vaux, Roland de, Milik, Jozef T. and Benoit, Pierre, eds., Discoveries in the Judaean Desert, vol. 2: Les grottes de Muraba'at (Oxford: Clarendon, 1961) 104–9.Google Scholar The get is known as Papyrus Murabba'at 20 or the “get from the Judaean Desert.” This get is dated 72 CE, and the fact that the couple lived on Masada confirms this early date.

8 mGit. 9:3. This line is part of an Aramaic tradition that is also given in a much shorter Hebrew form. It is difficult to know if this Aramaic tradition is an expansion of the Hebrew formula, or whether it is the traditional wording that was abbreviated to the Hebrew formula. The fact that R. Judah records his tradition in Aramaic, and the discovery of the almost identical wording in the Masada get suggests that the longer is the more ancient form. See my “Deuteronomy 24:1-4 and the origin of the Jewish Divorce Certificate,” JJS 49 (1998) 230–43CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

9 The right of women to divorce was concluded by several authors before the announcement of the Ṣeʾelim get. The article “Divorce” in JE 4 (1905) 624–28Google Scholar gave the standard opinion that a woman could demand a divorce for refusal of conjugal rights or impotence. Israel Abrahams (Studies in Pharisaism and the Gospels [London: Macmillan, 1917] 77)Google Scholar confirmed that this right extended to women whose husbands neglected to support them. Epstein, Louis (The Jewish Marriage Contract: A Study in the Status of the Woman in Jewish Law [New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1927] 201–5)Google Scholar has a long discussion that concludes that the rights seen in Elephantine and Roman law were enshrined to a lesser degree in early rabbinic practice and in biblical law. Others, writing after Milik's announcement, but before the publication of the Ṣeʾelim get, argued in the same way without appearing to know anything about the new document. Bammel, Ernst (“Markus 10.11 f. und das jüdische Eherecht,” ZNW 61 [1970] 95–101)CrossRefGoogle Scholar argued mainly from the Elephantine documents and did not cite Milik. Hugh Montefiore i n an appendix to the Anglican Synod Report Marriage, Divorce & the Church: the Report of a Commission Appointed by the Archbishop of Canterbury to Prepare a Statement on the Christian Doctrine of Marriage ([London: SPCK, 1971] 79–80)Google Scholar argued from the obligations of Exodus 21. Similarly, Ben-Zion (Benno) Schereschewsky in his article “Divorce” (EJ 6 ]1971] 122–37)Google Scholar argued from the Exod 21:10–11 obligations, citing the rabbinic discussions based on this. Amram, David Werner (The Jewish Law of Divorce According to Bible and Talmud [Reprint of undated original; New York: Sepher-Hermon, 1975] 57–58)Google Scholar discussed the ways in which a husband was forced to grant a divorce. Several articles in The Jewish Law Annual 4 (ed. Jackson, Bernard S.; Leiden: Brill, 1981)Google Scholar argued for the right of women to force a divorce from their husbands. Edward Lipinski (“The Wife's Right to Divorce in the Light of an Ancient Near Eastern Tradition,” 9–26) argued mainly from the ancient Near Eastern background, in which it was possible for women sometimes to gain a divorce, but he also cites the Ṣeʾelim get. Rabello, Alfredo (“Divorce of Jews in the Roman Empire,” 79–102,Google Scholar esp. 93-99) argues from the woman's rights under Roman law, but points out that later rabbis enforced these rights (m.Git. 9.8). Friedman, M. A. (“Divorce upon the Wife's Demand as Reflected in MSS from Cairo Geniza,” 103–26) showed that the medieval commentators also understood the Mishnah in this way.Google ScholarShilo, Shmuel (“Impotence as a Ground for Divorce: To the End of the Period of the Rishonim,” 129–43) argued from the laws of a husband's impotence inGoogle Scholartimes, Talmudic, and Washofsky, Mark (“The Recalcitrant Husband: The Problem of Definition,” 144–66)Google Scholar showed that this law allows a woman to divorce her husband even in modern Israel.

10 Marriage vows included material and emotional support (as defined by Exod 21:10-11) so divorce could be demanded if there was a refusal of conjugal rights (m.Ketub. 5.6) or a refusal to support her (b.Ketub. 77a). Emotional neglect was expanded to include cruelty or deprivation of freedom (m.Ketub. 7.2-5). Procreation was considered as a positive law, so anything that interfered with this could be grounds for divorce, such as inability of various kinds (m.Ned. 11.12) or something which caused revulsion (m.Ketub. 7.9). For further details, see my forthcoming book on the Jewish background of divorce and remarriage.

11 In particular, the Hillel-Shammai debate concerning how long a man was allowed to refuse conjugal rights (m.Ketub. 5:6), and the description of the minimum material support, which assumes a regular pilgrimage to Jerusalem (m.Ketub. 5:8).

12 As in b.Ketub. 77ab. It is not certain that these Amoraic commentators knew what was actual practice in the second century.

13 The marriage and divorce texts are published with a useful commentary by Cowley, A. E. (Aramaic Papyri of the Fifth Century BC [Oxford: Clarendon, 1923]) andGoogle ScholarKraeling, Emil G. (The Brooklyn Museum Aramaic Papyri [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953]).Google Scholar These and the other texts from Elephatine have been reedited and translated in Porten, Bezalel and Yardeni, Ada, Textbook of Aramaic documents from Ancient Egypt (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1986-1996).Google Scholar The new edition uses a completely revised numbering system.

14 UC15=B2.6; K2=B3.3; K7=B3.8 with slight variations.

15 , PhiloSpec. leg. 30.Google Scholar

16 Sandmel, Samuel, Philo ofAlexandria: An Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979) 134.Google Scholar

17 In his Philo's Place in Judaism: A Study of Conceptions of Abraham in Jewish Literature (New York: KTAV, 1971)Google Scholar he tried to show what Ginzberg's Legends and Wolfson's Philo had showed, that dissimilarity was as common as similarity, and similarities were more often with rabbis who flourished long after Philo. This is his own summary of what that work achieved, as stated in , Sandmel, Philo of Alexandria, 133. SeeGoogle ScholarGinzberg, Louis, Legends of the Jews (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1956); andGoogle ScholarWolfson, Harry A., Philo: Foundations of Religious Philospohy in Judaism (2 vols.; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968)Google Scholar.

18 Brewer, David Instone, Techniques and Assumptions in Jewish Exegesis before 70 CE (Tübingen: Mohr/Siebeck, 1992).Google Scholar

19 t.Ketub. 4:9; parallels at y. Yebamot. 15.3; y.Ketub. 4.8; b.B.Me. 104a.

20 According to the context of the debate in b.B.Me. 104a.

21 R. Judah's summary of the “essence” of the get in m.Git. 9:3 is in Aramaic. This phrase was already in use at the end of the first century, as seen in the Masada get.

22 As in K7=B3.8 and C18=B6.4.

23 The gloss “two” is found in the Peshitta, Samaritan Pentateuch, Vulgate, Targum Pseudo-Jonathan and Targum Neofiti. The only versions in which it does not appear are the Masoretic and Targum Onkelos, which was edited to agree with the Hebrew text.

24 Matt 19:5; Mark 10:8; 1 Cor 6:16; Eph 5:31.

25 The Qumran documents taught monogamy, CD 4.20-5.6; 11QT 57.15-19; see my “Nomological Exegesis in Qumran ‘Divorce’ Texts” (Revue de Qumran 18 [1998] 561–79)Google Scholar.

26 For example, b.'Abot. 2.5: “He who multiplies wives multiplies witchcraft”; b.Yebamot 44a: polygamy creates strife in a house, and no more than four wives are permitted so that each gets their conjugal rights at least once each month. The Herem of R. Gershom of Mayence (960-1040 CE) finally prohibited polygamy (Responsa “Asheri” 42.1), probably in 1030 at Worms (the document has not survived), but it had probably ceased to be practiced long before this.

27 Josephus recorded that Salome divorced by issuing a repudium, a Roman divorce certificate (Ant. 15.259-60). Other women in the Herodian family were likewise known to divorce their husbands (Herodias [Ant. 18.109-11]; Berenice, Drusilla, and Mariamme [Ant. 20.141-47]). Even Josephus's own wife walked out before he could divorce her, but without giving him a divorce certificate of any kind (Vit. 415).

28 “Some time afterwards Salome had occasion to quarrel with Costobarus and soon sent him a document dissolving their marriage, which was not in accordance with Jewish law. For i t is (only) the man who is permitted by us to do this, and not even a divorced woman may marry again on her own initiative unless her former husband consents. Salome, however, did not choose to follow her country's law but acted on her own authority and repudiated her marriage, telling her brother Herod that she had separated from her husband out of loyalty to Herod himself” (Ant. 15.259–60 [trans. Marcus, Ralph and Wikgren, AllenGoogle Scholar; LCL; 16 vols.; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963] 8. 123).

29 This link was pointed out in Falk, Ze'ev W., Introduction to Jewish Law of the Second Commonwealth (Leiden: Brill, 1978) 2. 310-11Google Scholar.

30 This was originally an ancient Near Eastern technical term for “divorce.” See Yaron, R., “On Divorce in Old Testament Times,” Revue Internationale des droits de l'antiquité 3 (1957) 117–28,Google Scholar esp. 117-19; Westbrook, Raymond, “Prohibition of Restoration of Marriage in Deuteronomy 24:1–4” in Japhet, Sara, ed., Studies in Bible, 1986 (Scripta Hierosolymitana 31; Jerusalem: Magnes, 1986) 387–405,Google Scholar esp. 399-402.

31 Falk, Introduction to Jewish Law, 2. 311.