I

Given that later Greek comedy, especially the work of Menander, is characterized by its preoccupation with domestic life, it is remarkable how little attention has been paid to the houses that feature in the plays. Perhaps one reason for this is that we do not normally look to drama for meticulous evocations of settings or buildings: we tend to associate topographic details more with literary genres such as epic or narrative fiction. Certainly drama is different from these other genres, and somewhat more restricted, in the ways that it creates a sense of place; but it is surprising just how much incidental descriptive detail the plays contain and what this material can reveal to us. The houses in Greek comedy are important in two distinct ways. In the first part of this article, I demonstrate that they constitute good evidence for real-life Greek houses of the period, and, indeed, they are more valuable as historical source material than has generally been recognized. In the second part, I argue that comic houses are significant in a thematic and conceptual sense within the world of the plays.

Modern scholarship on the classical Greek house has a predominantly archaeological bent. In the two most important recent books on the subject, Lisa Nevett and Janett Morgan both criticize previous generations of historians for their over-reliance on literary sources, and deliberately downplay the significance of textual evidence in relation to material remains.Footnote 1 There are several good reasons for adopting such an approach, including the rejection of traditional hierarchies within the discipline of classical studies, the scarcity of relevant texts, and the cautionary observation that literary descriptions do not always match the remains of real houses. It may be thought that the documentary value of imaginative literature – which after all was not written for the purpose of furnishing future historians with ‘evidence’ – is inherently questionable.Footnote 2 As Morgan observes,

We obtain our impressions from excerpts that are incidental to wider narratives or derived from fantastic situations. We try to understand life in the classical Greek house from studying the domestic behaviour of royal families in tragedies or the ideological descriptions of philosophers. The arrangements in each of these cases are serving the needs of the author and narrative rather than offering a true reflection of private life in a classical Greek household.Footnote 3

Nevertheless, I suggest that this contrast between ‘the needs of the author’ and the ‘truth’ about real life is variable rather than absolute. Rather than devalue or reject literature entirely, we need to distinguish more clearly between different types of literary text. It may well be that certain genres are more useful to the historian than others. Obviously the sort of milieux described in genres such as tragedy or epic are usually so far removed from everyday life that their direct evidential value is low. Philosophical texts offer a more variable, complicated reflection of life, though Morgan is no doubt right to see them as ideologically slanted or otherwise oblique in their representation of reality. Oratory is a more controversial category: most scholars have tended to treat lawcourt speeches as straightforward reflections of real-life settings, events, and popular beliefs, but Morgan prefers to emphasize their artificiality, arguing that their images of domestic life are to be read as rhetorical or ideological constructs rather than neutral or normative descriptions of reality.Footnote 4

Where does comedy fit into the picture? Oddly, it has not been discussed very much in this context. References to ancient comedies are found here and there in modern discussions, often in parentheses and footnotes, but there has been little explicit interest in comedy as a specific category of literary evidence. It is unclear why this should be so. Perhaps it is assumed that comedy contains so many jokes, exaggerations, or fantastic elements that it is automatically ruled out of consideration as a serious historical source.Footnote 5 Perhaps it is seen as unacceptably ‘ideological’ in much the same way as other genres.Footnote 6 Or perhaps it is supposed that the world of comedy constitutes some sort of heterocosm or alternative reality rather than a recognizable version of real-life Athens.Footnote 7

At any rate, when historians of the classical Greek house discuss literature at all, their main focus is not on comedy but on other genres. A couple of fourth-century texts in particular – Xenophon's Oeconomicus (9.2–5) and Lysias’ speech On The Killing of Eratosthenes (1.9–10) – have been repeatedly cited and discussed: these are described by Nevett as ‘offer[ing] the most detailed picture of the organization of a household of any of our textual sources’, despite their interpretative problems.Footnote 8 But in fact Greek comedy can be seen as offering a more detailed and revealing picture than either of these texts; it is just that it has never been as thoroughly investigated. The remains of lost comedies contain many important snippets and glimpses of domestic settings that have never been brought fully into the discussion. Their fragmentary state means that they give only an incomplete picture, but collectively they contain a good deal of information. One comedy in particular – Menander's Samia, which survives in a more complete state – happens to contain a lengthy description of a domestic interior which is more detailed and, arguably, more realistic, than those seen in Lysias or Xenophon.Footnote 9

It is not just the quantity of information or the degree of specific detail they contain that makes these comic sources so important. I suggest that comedy is intrinsically more valuable as evidence for real life than any other genre of Greek literature. Of course, comedy cannot be treated as straightforwardly or completely realistic. Extreme caution is needed, and (as I emphasize in what follows) we always have to be on the lookout for humorous exaggerations and distortions of one sort or another.Footnote 10 Nevertheless, comedy is popular mass entertainment. It centres on the sort of experience with which average audience members can identify. It depicts a world that (unlike the world of tragedy) can be clearly pinned down in specific temporal and geographical terms. Its action is set in the present day. It has a penchant for the low, the banal, the unglamorous, the messy, the quotidian. And it is packed with incidental details that are just there in the background, rather than (as in Xenophon or Lysias) the main focus of attention.

As I have said, I am thinking primarily of fourth-century comedy, and especially the comedy of Menander, which has long been renowned for its naturalism (as in the much-quoted saying of Aristophanes of Byzantium: ‘O Menander! O Life! Which of you imitated which?’).Footnote 11 But fifth-century comedy should not be ignored. Even though the main focus of Aristophanes and his contemporaries is on political and fantastic themes rather than everyday families and their affairs, and even though their treatment of space and mise en scène is eccentric,Footnote 12 the plays and fragments of ‘old’ comedy still contain valuable information. Some caution is needed, but it is usually possible to distinguish what look like normal features of everyday houses from what look like fantastic or ludicrous elements. Consider, for instance, the house of Philocleon in Wasps, the most fully described house in extant Aristophanes.Footnote 13 If we discount its manifestly absurd aspects (such as the fact that it seems to consist largely of openings and passageways large enough for Philocleon to pass through, or the fact that it is surrounded by an enormous net to prevent him escaping), what remains is a carefully detailed description of a building which, if not exactly realistic, is still supposed to represent a ‘typical’ fifth-century family house for the purposes of the play.

In what follows I examine exactly what the comedians have to tell us about Greek houses, arranging the material feature by feature rather than author by author. I am concerned specifically with the realistic verbal description of comic houses – that is, their architecture, layout, use of space, fittings and furnishings, and other such details – in the words of the characters. I have nothing much to say about their visual presentation in the theatre, a subject already exhaustively discussed by others,Footnote 14 though aspects such as stage production and dramatic function will be mentioned from time to time. For the sake of completeness, I include all surviving references from Greek comedy of all periods.Footnote 15 However, apart from one or two parallel passages cited where relevant, I have preferred not to include any discussion of Roman comedies, even though they contain plenty of domestic details, as well as a few interesting extended descriptions (such as the interior scenes in Plautus’ Mostellaria and Bacchides and Terence's Eunuch). This is because we can never be certain whether any given detail in a Roman version is taken from a Greek model or whether it has been updated in some way to reflect a Roman setting or Roman domestic architecture.Footnote 16

II

Fourth-century comedies mostly depict a pair of family homes situated side by side in an urban setting. Typically, one of the families featured is wealthier than the other, but their respective houses are not clearly differentiated. The only place in which a contrast is marked is Menander's Samia (592–3), where the house of Nikeratos is assumed to be in poor condition (its roof is leaky and in need of substantial repair). The plots of the plays, as well as their staging, require the two houses to be situated very close together. Such houses might be imagined as adjoining within the same block, or closely adjacent, as in real-life Athenian streets.Footnote 17 We have a couple of references to a narrow passage (stenôpon) separating a house from its neighbour: the cook in Hegesippus’ Adelphoi (fr. 1) imagines that people passing through this alleyway will be greeted by delicious smells drifting out from his kitchen, while Thrasonides in Menander's Misoumenos, locked out of his own house, is forced to pace up and down all night in the alley by his door (πρὸς ταῖς ἐμαυτοῦ νῦν θύραις ἕστηκ' ἐγὼ | ἐν τῶι στενωπῶι περιπατῶ τ' ἄνω κάτω, 6–7).

No trace survives of any physical description of the exterior of these buildings, and nothing is said about their architecture, fabric, or building materials. Perhaps such features were visually represented on the stage-building, or perhaps the playwrights preferred to leave them up to the audience's imagination. The only exterior detail that is described is the doorway. Just outside the door one might find a shrine, an altar, or a herm;Footnote 18 we even find a reference to the practice of burying the head of a squill by the hinge of the front door as a way of averting evil spirits.Footnote 19 For weddings, funerals, and other specific ritual purposes, the doorway could be decked out with garlands or other paraphernalia.Footnote 20 The door might have some sort of porch or vestibule directly in front of it: the word prothuron is found in this sense in a few places, though it is not clear what type of structure is being described.Footnote 21

The front door is a recurrent focus of interest within the plays because it is the main route for the entrances and exits of characters.Footnote 22 The door itself is not normally described in detail. The singular thura and the plural thurai seem to be used interchangeably, but it can normally be assumed that we are dealing with stout double doors, opening inwards and lockable from the inside with a bolt or other sort of fastening.Footnote 23 A running joke throughout Greek comedy, attested in the fifth century but used more and more often thereafter, relies on the perception that such doors tended to creak rather loudly upon opening. This noise is sometimes heard, and referred to in a self-consciously silly manner, numerous times within a single play.Footnote 24 For dramatic purposes these houses are normally treated as having a single external door, but exceptionally a second entrance might be mentioned, as in Menander's Dyskolos, where Sikon, denied entry to Knemon's house via the front door, asks: ‘Shall I try another door? (ἐφ' ἑτέραν βαδίζω | θύραν; 925–6). Perhaps Sikon's words are supposed to be funny, but archaeological and literary evidence confirms that, even though a single door was much more common, some Greek houses did have more than one external door.Footnote 25

A surprisingly large number of comic passages are concerned with the particulars of bolts, seals, and locks.Footnote 26 Sometimes it seems that an unusual or innovative sort of device is being described. Characters in Menander (Misoumenos fr. 8) and Aristophanes (Thesm. 414–28) take care to emphasize the fact that they are using a ‘Spartan key’, which (like a modern key) could lock a door from either side;Footnote 27 and a door in Poseidippus’ Galatian is fastened with a special type of latch known as a ‘raven’ (κόρακι κλείεθ' ἡ θύρα, fr. 7). Ordinary, trivial-seeming details such as this are particularly revealing. They not only preserve the sort of information that never survives in material form, but they also reflect the extent to which these comedies are preoccupied with the idea of domestic privacy and security – an aspect to which I shall return.

With one important exception (Menander's Samia – see below), the internal plan and layout of comic houses is obscure, and the exact number and arrangement of rooms is left to the imagination. The size of a house might sometimes be implied but not stated – as in Menander's Perikeiromene (538–43), where Moschion's house must be large enough for family members to be unaware of one another's presence or absence, and for Moschion himself to be able to retreat ‘to a room out of the way’ for a bit of peace and quiet.Footnote 28 (By contrast, Moschion in Samia 94–6 has to go outdoors to get some privacy, and plot developments in that play require that conversations within the house can be easily overheard.) Sometimes reference is made to an upper storey or roof, accessed via stairs: the upper level might contain bedrooms or other spaces big enough to hold rituals or private parties (notably including the female-only Adonia festival).Footnote 29

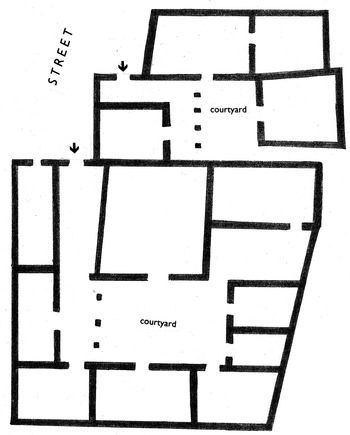

No doubt every house, in comedy and in real life alike, was slightly different, and we should not assume the existence of a single ‘typical’ model.Footnote 30 Nevertheless, on the basis of archaeological remains it has been concluded that ‘the classical Greek house shows a common, underlying conception, even though the actual working out may vary considerably’.Footnote 31 The majority of Greek houses known to us from Athens and other city-states were constructed around a central courtyard with rooms opening directly off it, as in Figure 1 (showing two adjoining Athenian houses from the fifth century).Footnote 32 As has been widely observed, this sort of design seems to have two main functional advantages: it ensures a high degree of privacy from the outside world and a high degree of visibility and control over movement within the house, since everyone, family members and visitors alike, must pass through the courtyard.Footnote 33 This type of plan may not correspond to every comic house, but several of our plays do explicitly mention a courtyard.Footnote 34

Figure 1. An adjoining pair of fifth-century Athenian houses.

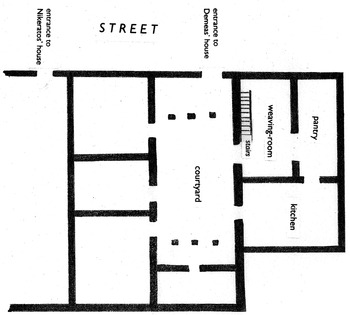

The information provided at various points throughout Samia not only shows that Demeas’ house has a central courtyard but also, extraordinarily, allows us to sketch out a notional plan of most of the house. In the prologue (40–6) Moschion mentions an upper storey, which was evidently spacious and equipped with hiding places, since he is able to sit and watch the women's Adonia celebrations, and later have sex with one of the participants, without being seen or heard. Fuller details are provided by Demeas, who delivers a long narrative of an interior scene at the start of Act III (219–64). The narrative concerns the hustle and bustle of preparations for a wedding feast: the master of the house instructs the women to clean the house and start making food, but he is so keen to get things moving that he himself assists them in their work. The crucial portion (225–41) is worth quoting at length:

The baby had been chucked down on a couch out of the way and was howling. The women kept shouting ‘Flour! Water! Oil! Coal!’ all at the same time. I myself went to fetch one or other of these things and take it to them. I happened to go into the pantry, and I did not come out straightaway because I was taking my time looking for something and taking out more supplies. At the same time as I was doing all that, a woman came down from the upper storey and went into the room that was directly in front of the storeroom – that room happens to be a weaving room, built in such a way that one has to pass through it in order to go upstairs or go to the pantry. The woman was the nurse of Moschion, a rather elderly person, and nowadays free, though she used to be a slave of mine. When she saw the child crying and unattended, she went up to it. Since she didn't know I was in the room to hear her, she thought that she could talk to it freely.

A few lines later, the narrative continues when a young slave-girl comes in ‘from outside’ (ἔξωθεν εἰστρέχοντι, 252): this must mean that she enters the weaving room from the courtyard.Footnote 35 The girl remonstrates with the nurse and informs her that Demeas is actually in the pantry within earshot (256–7). A little later still, when the women have left the weaving room, Demeas emerges and makes his way out of the house via the courtyard (262–3).Footnote 36 Putting all these details together, we can draw a reasonably accurate diagram of the house (Figure 2).Footnote 37

Figure 2. Demeas’ house as described by Menander in Samia.

One aspect of Demeas’ household that is especially worth observing is that it does not have separate areas for men and women. In the scene above and elsewhere, Demeas mixes freely with the women of the household, and even joins in with what we might have supposed were exclusively feminine activities. Nor, evidently, do the women in Nikeratos’ house in the same play have private quarters, since Plangon is unable to breastfeed her baby in secret (540–2). (Another relevant passage for comparison is Menander's Perikeiromene [519–20], where Polemon has free access to the wardrobe or dressing room of his mistress, Glycera.) Whether or not the gendered segregation of domestic space was normal in classical Greece is a difficult question to answer. Those literary sources which have traditionally been treated as evidence, such as Lysias and Xenophon, do appear to describe a strict separation into men's quarters and women's quarters. However, as already mentioned, recent scholars have questioned the supposedly normative image that these texts give us. In particular, it has been pointed out that no easily identifiable ‘women's quarters’ or binary structures (i.e. distinct areas or separate suites of interconnecting rooms) can be seen in the archaeological evidence, and it has been suggested that the segregation of family members was much less important than the protection of female householders from male visitors or intruders.Footnote 38

Comic evidence cannot definitively answer the question, but it does seem to suggest that the archaeologists are correct. Just two passages explicitly mention separate women's areas of the house, using the word gunaikonitis.Footnote 39 These texts have been widely cited as evidence for everyday life in an Athenian household, but perhaps the most significant fact about them is that neither of them describes a normative or real-life situation. Both texts are specifically concerned with a hypothetical or imaginary scenario: in each of them what we see is a husband's or householder's anxiety about adulterous lovers or other male intruders making their way nefariously into the household. Apart from these brief references, the plays are silent on the topic, but their plots and action generally seem to imply free interaction between the men and women in a house, along with complete freedom of movement. On balance, then, it is hard to know exactly what the word gunaikonitis was supposed to denote in reality. But it is clear, at least, that the corresponding word andron does not normally mean ‘the men's quarters’ as opposed to ‘the women's quarters’; it more accurately denotes the dining room.

Dining rooms are bound to be important in a genre that is so firmly associated with eating and drinking. But the comic evidence seems to show us something slightly different from the archaeological evidence. Many of the Greek houses that have been excavated have a room distinguished by certain features (such as an antechamber, mosaic floors or other decorations, or a raised platform big enough to accommodate dining tables or couches), suggesting that it was used for feasting or entertaining guests.Footnote 40 This room is typically labelled as the andron in archaeological floor plans and discussions, following the use of the word in this sense in a variety of literary texts.Footnote 41 But this word is found only once in comedy, in an unrevealing fragment of Aristophanes’ Babylonians where a character enquires ‘how many roof-beams does this andron have?’ (fr. 69). There are many scenes in which feasting and drinking are evoked, but there is no other mention of a so-called andron.

The word triklinion, by contrast, is found several times in comedy.Footnote 42 But it is striking that the sort of space it describes looks like an improvised setting, specially arranged according to the needs of the occasion, rather than a permanently furnished dining room. A triklinion was literally a space into which three couches were carried for the diners to recline upon. If more guests were invited, more couches could be brought in. This is precisely what is being described in a fragment of Eubulus, where a slave is ordered to bring up to seven couches (and the dining area is thus relabelled a heptaklinon).Footnote 43 The slave who arranged the dining room was known as the trapezopoios, and several other comedies featured such a character in action.Footnote 44 In other words, comic houses repeatedly seem to reflect a flexible use of space, suggesting that individual rooms may not have had fixed functions but could be reconfigured according to need.Footnote 45 (Such an approach, if correct, could also affect our perspective on ‘women's quarters’ as well as dining areas.) No doubt some houses had a permanent dining room set aside exclusively for that purpose, but it appears that entertaining did not actually require a special sort of room or a fancy tiled floor. Nevertheless, these comic scenes and their terminology are not necessarily inconsistent with the evidence of archaeology, nor should they be rejected as evidence. In fact, they may help us to interpret the material remains and suggest to us ways, irrecoverable through archaeology alone, in which observable domestic spaces were actually used in practice.

Given the importance of food in comedy, we might have expected to see more mention of the kitchen. Certainly we encounter plenty of comic cooks, but we have few glimpses of the settings in which they worked. Pherecrates wrote a whole play entitled Ἰπνός (The Kitchen or The Oven), which would have been a precious source of knowledge if only it had survived: its title and a few tiny fragments indicate ‘a domestically-centred comedy’, which may well mark it out as unusual for an ‘old’ comedy of the mid-to-late fifth century, but we can say little more than that.Footnote 46 Apart from a handful of passing references to kitchens,Footnote 47 the only relevant comic source (once again) is Samia, where we encounter a cook questioning his employer about his domestic set-up (286–92): he wants to know at what time to serve dinner, how many assistants will be available, whether there will be enough crockery, and whether or not the kitchen has a roof. But since no one answers the cook's questions, we never discover what the kitchen chez Demeas is actually like.

In many houses there will have been other rooms aside from the kitchen designated for food preparation, storage, cleaning, laundry, or other types of housework. Several such rooms feature in comic houses, and are given specific names: we find a couple of references to a pantry or storeroom (tamieion),Footnote 48 a room exclusively set aside for weaving cloth (isteon),Footnote 49 and some sort of cupboard for the storage of drinking vessels (kulikeion).Footnote 50

Practical activities or home industries might also spill out of the main house and occupy adjoining spaces – as in the plot of Antiphanes’ comedy Akestria (The Seamstress), which involved the conversion of an outbuilding or shed (klision) into a workshop (ergasterion) for embroidery:

[† if there is a workshop inside the house] he has converted the outhouse, which in former times was used as a stable for cattle and donkeys, into a workshop.

Pollux, who quotes the fragment above (fr. 22), adds the detail that the klision was directly adjacent to the house and separated from it by curtains (parapetasmata); however, it is not clear whether he is describing the ‘actual’ house (in the world of the play) or the use of the skene and stage properties to represent these buildings in the theatre.Footnote 51 A further complication is introduced by fr. 23, which hints that the supposed ‘workshop’ in this comedy may in fact have functioned as a brothel or a secret meeting place for lovers. Much is uncertain about this play, then, but its main action evidently centred on the minutiae of domestic geography and the relationship between a house and the buildings that surround or adjoin it. Furthermore, it was clearly interested in exploring the comic possibilities of party walls, property boundaries, and secret entrances – an interest which was shared by Menander's Phasma.Footnote 52 The plot of Menander's play, partly preserved in summary form, featured a woman who secretly gave birth to a daughter and hid her in the house next door; she later made a hole through the party wall so that she could visit her daughter, and disguised this entrance by decorating it as a domestic shrine and hanging curtains over the opening.Footnote 53 A scenario in Diphilus’ Chrysochoos (The Goldsmith) is more obscure but in some ways comparable: fr. 84 mentions an ὀπαία κεραμίς, a tile with a hole designed to allow smoke to escape from the house, which also happens to be just big enough to allow a young man to catch a glimpse of a beautiful girl on the other side.Footnote 54

Perhaps what we are looking at in Akestria is an example of a building that combined domestic/private and commercial/public activities side by side. This type of structure is found quite often among archaeological remains in various Greek settlements;Footnote 55 in literary sources it is unusual but not unparalleled. Comedy provides three further examples: in both Eubulus’ Pamphilus (fr. 80) and Menander's Theophoroumene (28–9) we see a private house immediately adjacent to an inn, and in Theopompus’ Althaea (fr. 3) a room in a house seems to be doubling up as a doctor's surgery or pharmacist's shop. It seems likely that the humour in each case arose from some sort of conflict between different uses of space, or some sort of threat to the privacy of the main characters.

A few references are found to water supplies and drainage facilities, though all are somewhat vague. In Menander's Dyskolos, Knemon's house has its own private well, located somewhere inside the house (presumably within the central courtyard, though this is not explicitly stated). This well turns out to be crucial to the plot, since objects or people repeatedly fall into it (189–91, 574, 620–5), but the scenes in question are narrated rather than acted out, and they do not include any detailed description of the well itself. In a couple of other comedies we see drainage channels being exploited for other uses: even though these uses are ludicrously far-fetched, I take it that they are still broadly ‘realistic’ in terms of the physical features that they evoke. Smikrines in Menander's Aspis seems to think that the women in his house are using the water course as a means of communicating (somehow) with the next-door neighbours.Footnote 56 Philocleon in Aristophanes’ Wasps, imprisoned in his own house, tries to escape by passing through the drain.Footnote 57 The two passages use the same word (ὑδρορρόαι), which seems to refer to a ground-level drain or a gutter.Footnote 58

Finally, the lavatory is a feature of the household that is decorously passed over by other literary sources – all the more reason, then, to be thankful for the evidence of the comedians, with their mentioning of the unmentionable and their fixation on the squalid and excremental. In Eubulus’ Cercopes (fr. 53), an unidentified character describes the luxurious habits of the Thebans, including the fact that ‘every house has a toilet (koprôn) right by its doorway: there is no greater good than this for mankind, since the man who's desperate for a shit but has to make a long run for it, biting his lips and groaning, is a ludicrous sight’. The tone of exaggerated admiration implies that many Athenian homes did not have their own lavatory near to hand – a state of affairs that is apparently confirmed by a number of similar passages from Aristophanes.Footnote 59 The Kinsman in Thesmophoriazusae, for instance, imagines a scenario in which a young wife uses an emergency nocturnal dash to the toilet as an excuse to pop outside and meet her lover (477–89); as in the Eubulus fragment, we are meant to imagine an outdoor privy situated near the door of the house, inconveniently far from the upstairs bedroom.Footnote 60 Ecclesiazusae features a grotesquely extended sequence (320–71) in which Blepyrus, gravely troubled by the state of his bowels, cannot find anywhere to relieve himself: it seems that he has no toilet either inside or immediately adjacent to his own house, and cannot even find a private spot within easy reach. The humour of all these episodes (such as it is) depends on the spectators finding the situation basically credible and relating it to their own experiences.Footnote 61

III

I have suggested that all these little details – many of which are only minimally or obliquely revealing by themselves – add up to a substantial and important body of evidence. Assembled together in this way, they seem to form, in effect, a composite image of a Greek house in the period when the plays were performed. That is not to claim that the resulting image is realistic in every conceivable aspect, or that all the features discussed here were straightforwardly typical, or that all houses, either in comedy or in real life, were alike. What is important is that many individual details are preserved in these plays, and that they feature in the background as everyday, apparently unexceptional features of domestic life. Furthermore, as we have seen, it is striking that most of these details are found repeatedly in more than one source, thus lessening the likelihood that they have been invented or shaped to suit the needs of any specific author or text. I conclude that they can be used, with advantage, alongside the evidence from archaeology.

But comic houses are not just a good source of evidence for the social historian. They are also significant to the literary critic, in terms of their meaning and function within the plays. By the time of the mid-to-late fourth century, Greek comedy had become more or less synonymous with domestic comedy. These plays, in contrast to the world of ‘old’ comedy, are relentlessly concerned with intimate family relationships, private business, and the sort of behaviour and conversation that normally takes place behind closed doors. They are also preoccupied with questions of property, inheritance, and ownership. All of this means that these houses are central to the works in which they appear. They shape and contain the action. In their symmetry, as well as their paradoxical combination of proximity and separation, they provide the structural framework in which the plots unfold. To a large extent they symbolize the characters and their relationships; it is no coincidence that oikos in Greek, like ‘house’ in English, can refer to the family members as well as the building in which they live.Footnote 62 They embody personal and social status, family ancestry, and financial security. In sum, these houses are not just a convenient backdrop for the action; they are, in a real sense, what these plays are all about. Plot, character, and setting are all intimately connected in domestic comedy, in a way that is not paralleled in other forms of classical drama.

The meaning of comic houses is heavily dependent on their realism, an aspect which I have emphasized. Of course, there are several ways in which fourth-century comedy can be seen as unrealistic, such as its extreme formal stylization, its limited range of ‘stock’ situations, or its debt to tragic motifs and plot patterns.Footnote 63 But the crucial point is that the houses themselves are apparently normal and ordinary. They are not like the grand houses of tragedy; they are not especially unusual or distinctive; not one of them stands out as a memorable literary creation in its own right. They are significant and symbolic precisely because of their ordinariness: that is, they represent the sort of house in which any of the spectators might themselves live.Footnote 64 The Athenian street scenes evoked by Menander and other later Greek comedians, with their adjacent pairs of houses, are highly conventional and artificial, but at the same time they are a genuine reflection of everyday life – even, perhaps, a microcosm of Greek society. (In this respect, the sort of world depicted in these plays might almost seem to anticipate postmodern literary techniques, as exemplified in George Perec's experimental novel La vie. Mode d'emploi (1976), in which a minutely particularized Parisian apartment block functions as a microcosm of all human life.)

Many of these observations about Greek comic houses could apply equally well to the houses or apartments in modern television sitcoms (a genre to which Menander's comedy is often compared). The domestic settings in Friends, Frasier, My Family, The Big Bang Theory, and hundreds of other examples similarly combine stylized elements (such as open-plan living, quirky interior décor, and so on) with a significant degree of verisimilitude. They are precisely the sort of setting required for the plots to unfold in; and they typify the lives and personalities of their inhabitants. They do not perhaps meet the criteria for realism in every respect, but they represent the sort of home that the target audience member could imagine themselves inhabiting. Nevertheless, it is instructive to point out one crucial difference between the two types of mise en scène. In sitcom homes (as in most modern theatrical productions) the audience can actually see the domestic interior: all the action takes place indoors but in full view, because the stage or television set represents the rooms of the house or apartment. In ancient comedy, by contrast, the interior scenes are almost completely invisible: either the action takes place outside in the street (another way in which these plays flout strict realism), or it must be described through narrative rather than acted out directly in front of us. There is a huge difference between what we see and what we are induced to imagine.

These considerations explain why I am not concerned here with stage production or the appearance of the skene. Most of the descriptive details recorded above come from narrative sections and were not physically represented in the theatre. The comic house, in other words, is essentially an invisible and virtual construct. For this reason the notion of everyday realism is even more important for understanding how the houses work within the plays on a conceptual level. In spite of all the nitty-gritty detail that they provide, there is an awful lot that the plays do not tell us; and so we are required to imagine all these unseen interiors for ourselves, supplementing the information in the text on the basis of real-life experiences and personal memories. In a sense, each individual spectator or reader ‘builds’ these houses inside their own head. This type of cognitive process is memorably evoked by Gaston Bachelard in his book The Poetics of Space, which treats the house in literature (in a broad sense) as a locus for memory and imagination. According to Bachelard, a house is ‘a body of images’ or ‘a privileged entity for a phenomenological study of the intimate values of inside space’. Whenever we encounter a fictional house, ‘the reader who is “reading a room” leaves off reading and starts to think of some place in his own past… To read poetry is essentially to daydream.’Footnote 65 Even though Bachelard has nothing to say about classical literature as such, his insights can readily be applied to our ancient comedies.

An aspect of the poetics of domestic space that especially interests Bachelard is ‘the dialectics of outside and inside’, and the fact that, when we conceptualize a real or imaginary house, we inevitably do so from either an interior or an exterior perspective. One of the reasons why people enjoy reading about houses, he argues, is that we are all naturally afflicted by a voyeuristic sense of curiosity: literature allows us the access to other people's homes and private lives which we desire but are normally denied.Footnote 66 Once again, even though Bachelard is thinking exclusively of modern poetry and novels, this inside/outside dichotomy is very obviously applicable to Greek comedy. It helps us to make sense of the plays’ persistent focus on the privacy and security of its houses, their unusually specific interest in locks and bolts, their tantalizing glimpses of the interior domain, and the huge amount of stage business involving the open or closed front door.Footnote 67 This conceptual dichotomy can also be closely linked to the archaeologists’ conclusion (mentioned above) that privacy was the most important principle underlying the design of real-life Greek houses.Footnote 68

The interpretative significance of the Greek comic house lies chiefly in the fact that, for the duration of the plot, its doors are opened and its private secrets and problems spill out into the public domain. This scenario (so it is implied) marks a sharp contrast with the normal state of affairs, in which houses do successfully control their inhabitants’ personal relationships, and in which it is possible to be almost totally oblivious of other people's affairs. Perhaps we could read the plots of these comedies as springing from deep anxieties about what might happen when Athenian citizens open their front doors and come into contact with the world outside. Alternatively, we might choose to see them as embodying a ‘carnivalesque’ inversion of normal life: they could be treated as a rare and limited occasion when the normal categories of public vs private, inside vs outside, visible vs invisible (and so on) are jumbled up, before the plays’ happy endings mark a return to the safe and secure status quo.Footnote 69

No matter what our own perspective on this material may be, it strikes me that all of us, as modern scholars and students of the ancient world, are in a very similar position to the audience in the theatre or the person in the street in classical Athens. We stand outside these houses, peering in with intense curiosity, desperate to know more, but able to discern only tantalizing glimpses of a world that is basically inaccessible to us. Investigating domestic life in classical Greece can be a frustrating business. Nevertheless, despite the nature of the subject and the shortage of evidence, the houses in comedy can tell us much more than we might have imagined.