Vox populi redux

In May 2018, the Spanish left-wing political party Podemos organized a digital party referendum, as they called it, on its leadership. What had happened? Pablo Iglesias, the party's outspoken leader, and his life partner Irene Montero, the party's parliamentary spokeswoman, had purchased a relatively luxurious €600,000 home with a swimming pool and a guest house. According to many within and outside the party this was a hypocritical act, running counter to earlier public statements about perverse mechanisms on the housing market. To re-establish its credibility, the leadership supported an unplanned vote of confidence, organized via the party's website, saying, ‘if they say we have to resign, then we will resign’ (Marcos Reference Marcos2018). Although the words ‘party referendum’ were being used, the procedure could just as well be likened to a (party) recall: a voting procedure to accept or decline a leader already in the saddle. The couple ultimately survived the vote, on 28 May 2018, after winning 68.4% of nearly 190,000 votes cast.

In March 2016, the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) in the UK organized an online poll, as they called it, to involve the wider public in the naming of a new research vessel: publicly funded, then why not publicly named, the reasoning went. The NERC suggested some names – Endeavour, Falcon, Henry Worsley, Sir David Attenborough – on which people could cast an online vote. The public was asked to suggest additional names, which could then also compete for support. The hashtag on social media became #NameOurShip. More than 3,000 additional names were suggested. Former radio presenter James Hand jokingly suggested ‘Boaty McBoatface’, which became an instant hit. This name ultimately won the online vote, with more than 124,000 declarations of support (four times more than second-placed: ‘Poppy-Mai’). The public's favourite, however, did not become the name of the ship, but only of one of the submersibles aboard. Jo Johnson, then minister for universities and science, decided to go along with the more traditional name RSS Sir David Attenborough (BBC News 2016). The formal line was that the online poll, although open to public input, was never meant to be a binding referendum.

These are just two illustrations (common practices rather than best practices) that take public voting on political actors and public governance issues well beyond the realm of traditional voting for politicians and their programmes. This is emblematic for the new 21st-century plebiscitary democracy that is reinventing long-existing methods (initiative, referendum, recall, primary, petition, poll) with new tools and applications (mostly and prominently online, occasionally also offline). The new plebiscitary democracy is a sprawling phenomenon that needs more encompassing scholarly research, as it comes in a great range of guises, with various possibilities and problems, and many questions still to answer. Hence, this article sets out to formulate a research agenda – necessarily open ended – based on an explorative review of new plebiscitary formats, developing on a substratum of older plebiscitary formats, which have in common:

• a focus on the swift aggregation of individually expressed choices – including electronic clicks, checks, likes and other signs of support – into a collective signal believed to be the voice of the demos or the vox populi, which tends to be revered (‘vox populi, vox dei’);

• a concentration of such citizen-inputted, aggregative processes on political actors and issues in public governance, tending to result in binary public verdicts (‘yes/no’, ‘for/against’);

• a belief in direct voting of a highly competitive and majoritarian sort (‘you vote, you decide’), centralizing mass and quantity, a bigger-the-better logic, a ‘democracy of numbers’ (cf. Lepore Reference Lepore2018).

The new plebiscitary democracy comes with a comparatively thin conceptualization of ‘democracy’, invoking the bare notion of a demos whose aggregated, amassed will is to steer actors and issues in public governance in a straight majoritarian way (cf. Della Porta Reference Della Porta2013; Hendriks Reference Hendriks2010; Powell Reference Powell2000; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999).Footnote 1 Unlike deliberative democracy (and more like, for instance, ‘stealth democracy’; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002), there is no sophisticated normative political theory in place from which plebiscitary practices are deduced and legitimated. Democratic claims develop in and around new plebiscitary practice. Such claims cannot be taken for granted, but neither can they be dismissed a priori. How and to what extent democratic claims are actually realized are to be determined by the type of research outlined in this article.

The adjective used in ‘plebiscitary’ democracy – the new incarnation as well as the older – refers to the more or less democratic use of plebiscites or ‘votations’. The latter is an umbrella term for various ways of taking votes beyond merely the ballot box of general elections.Footnote 2 Votations or plebiscites can be either bottom-up or top-down, issue-oriented or elite-oriented (more on this in the next section). The leader-dominated variant is one of the possibilities of plebiscitary democracy (cf. Green Reference Green2010: 5; Qvortrup et al. Reference Qvortrup, O'Leary and Wintrobe2018), not its one and only option.

‘May we have your votes now?’

In present-day, 21st-century democracy, the request ‘May we have your votes now?’ entails more than it used to. Not only has the ‘we’ taking and aggregating votes been enlarged, but so has the ‘votes’ that are being taken and aggregated. Citizens may still cast their votes in ballot boxes on election day, as citizens have done for decades. But nowadays they can also see them aggregated as digital signatures, checks, likes and various sorts of electronic declarations of support in the periods between election days. The actors initiating such votations can be other citizens, non-political and non-governmental actors, but they can also be political or governmental actors with an institutionalized stake in the political system à la David Easton (Reference Easton1965). The votations may be directed at political leaders and authorities that operate within the political system or at issues or topics in the public domain. They are not confined to formal democratic decision-making.

While conceptual stretching of the concept of voting is not uncommon – ‘voting with your feet’, popularizing some areas more than others, ‘voting with your purse’, supporting some brands more than others – the exploration here is primarily focused on practices that can be viewed as variants of ‘voting with your hands’ on public and political issues. This means that the focus is on contemporary – often device-clicking (Halupka Reference Halupka2014; Hill Reference Hill2013; Jeffares Reference Jeffares2014) – extensions of the longer-existing hand-raising, box-ticking and button-pressing activities of individuals that amount to a collective signal with regard to political leaders or issues of public governance. (Hence, I consider the naming of a publicly funded ‘flagship’ within the boundaries of the exploration and, for example, the digital vote for ‘best book of the year’ not). Such a constrained stretch of the public vote concept is both justifiable and urgent. New voting formats are spreading, changing democratic discourse and relations in ways not yet well understood.

We should differentiate the new plebiscitary democracy, which assumes human agency, including democratic action and discourse, from the strictly ‘instrumentarian’ surveillance systems that Shoshana Zuboff (Reference Zuboff2019: 20) describes as deeply ‘anti-democratic’, working towards a data-driven, behaviourist society model in which ‘the algorithms know best’ and in which political action is to be avoided (Zuboff Reference Zuboff2019: 433). Yuval Noah Harari (Reference Harari2017: 428–462) uses the term ‘dataism’ to denote the belief that refined algorithms can render democratic action and discourse obsolete in the not too distant future. The rival idea – ‘techno-activism’ – assumes that technology extends human agency and collective action.Footnote 3 The formats of the new plebiscitary democracy that are explored here largely follow a techno-activist approach to democracy, albeit with a particular, plebiscitary leaning. In exploring these formats, I do not negate the scope for technical applications with non-democratic and apolitical implications in dire need of investigation too; the examination of these, however, falls outside the scope of this article.

New plebiscitary, deliberative and established electoral democracy

As this article focuses on the sprawling phenomenon of 21st-century plebiscitary democracy, it will not delve deeply into the peculiarities of established electoral democracy (the rectangular box in Figure 1). The emerging 21st-century plebiscitary democracy (the circle on the left) is approached here as a set of additions to established electoral democracy, just like the deliberative turn at the end of the 20th century produced a set of additions (the circle on the right; cf. Warren and Lang Reference Warren, Lang, Lenard and Simeon2012).

Figure 1. New Plebiscitary, Deliberative and Established Electoral Democracy

Deliberative-democracy formats include random mini-publics, juries, citizens’ assemblies, consensus conferences, planning cells and the like, and are geared at thoughtful, reflective and transformative processes of public opinion formation (cf. Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Niemeyer, Neblo, Steenbergen and Steiner2010; Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000; Gastil and Levine Reference Gastil and Levine2005). Such formats have thus far received more encompassing attention in the democratic-innovations literature than the sprawling and nascent formats of new plebiscitary democracy. The latter are comparatively under-conceptualized, notwithstanding the existence of important alerts of related developments (cf. Cain et al. Reference Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2003; Green Reference Green2010; Keane Reference Keane2009; Rosanvallon Reference Rosanvallon2008; Rowe and Frewer Reference Rowe and Frewer2005). The subfield of new ‘digital-age’ democracy is covered by many studies, but these are to a large extent focused on versions with a deliberative or collaborative setup: digital town meetings, online discussion forums, Wiki-style law-making, hackathons, collaborative coding and similar formats for interactive co-creation (Mulgan Reference Mulgan2018; Noveck Reference Noveck2009, Reference Noveck2015). The more voting-oriented, plebiscitary versions have attracted some attention (e.g. Susskind Reference Susskind2018: 239–243),Footnote 4 but in terms of systematic theorizing and comparative analysis much ground is still not covered. Therefore, the central objective of this article is to take a next step in exploring and mapping the diversity of 21st-century plebiscitary democracy, and to formulate a tentative research agenda with regard to it.

The world of general elections for parties and candidates is extensively documented (e.g. Diamond and Plattner Reference Diamond and Plattner2006; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999; Sartori Reference Sartori2016 [1976]). For our present purposes, the conceptual distinction between plurality/majority systems and systems of proportional representation is most useful and relevant. Although winner-takes-all systems of plurality/majority voting at face value seem fertile breeding grounds for new plebiscitary practices, we do not yet know whether the emerging formats of plebiscitary democracy are taking root any less in electoral systems of proportional representation. This is actually one of the questions that requires more systematic research, the basic lines of which will be drawn in the concluding section. There the relationship between deliberative and plebiscitary additions to representative democracy will also be interrogated.

The new plebiscitary democracy: emerging formats

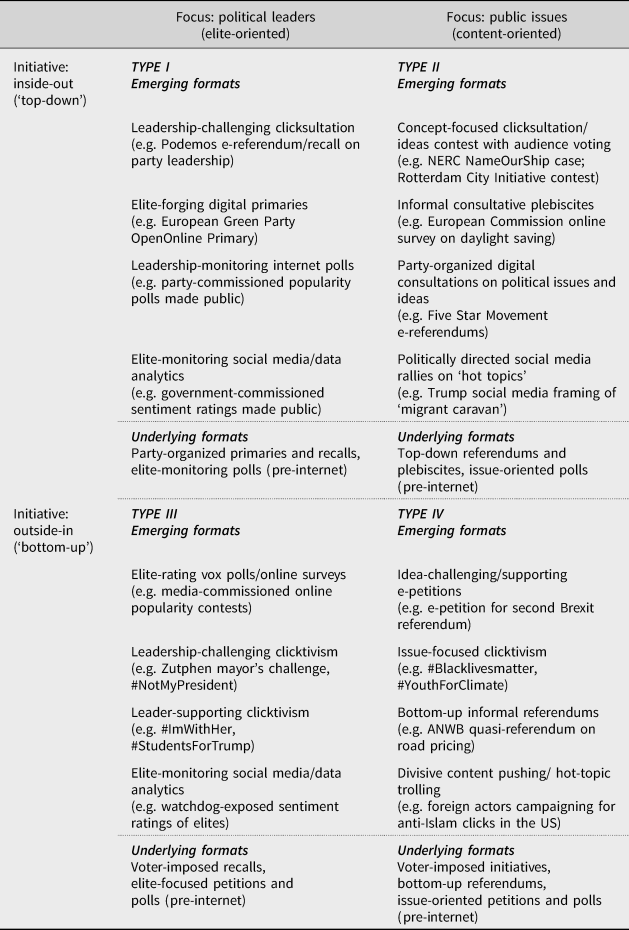

In this section, I develop a tentative typology of the new plebiscitary democracy, distinguishing between four types of emerging plebiscitary formats. The new formats regenerate longer-existing methods (initiative, referendum, recall, primary, petition, poll) with new tools and applications. The Podemos and NERC votations mentioned as opening examples illustrate, in a very specific way, two of these general types: Type-I votations that work ‘inside-out’ – pushed by parties or institutions that make up the political system – and are ‘leader-focused’ (the Podemos example); and Type-II votations that also work ‘inside-out’ but are ‘issue-focused’ (the NERC example).Footnote 5

There are also new votations emerging that work from the outside in – pushed by actors or groups beyond the set of parties and institutions that are commonly understood as the political system. Ideal-typically, they may focus their vote-collecting activities on political elites and leaders – Type-III votations – or on particular public issues – Type-IV votations. The resulting matrix of ideal-typical options is depicted in Table 1. In democratic practice, we may see combinations or clusters of such ideal types developing, but to understand these properly we first need to see the underlying mechanisms and diversity of formats. This is what the next two subsections will focus on.

Table 1. The New Plebiscitary Democracy: A Matrix of Emerging Formats

Emerging formats: inside-out

Type-I and Type-II votations share a top-down or more precisely an inside-out logic of mobilizing choice signals and interpreting them as an aggregated public choice. They reinvent, with new formats, longer-existing mechanisms like party primaries, party recalls and top-down (i.e. government-initiated) referendums and (pre-internet) opinion polling steered by political actors and public authorities (cf. Altman Reference Altman2017; Cain et al. Reference Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2003; Hollander Reference Hollander2019). When these initiatives involve the aggregation of electronic clicks, the term ‘clicksultation’ is used as a contraction of ‘clicks’ and ‘consultation’.Footnote 6 Clicksultation operates top-down, or more precisely inside-out, and should be distinguished from ‘clicktivism’ (Halupka Reference Halupka2014; Lindgren Reference Lindgren2015), which combines ‘clicks’ with ‘activism’, operating bottom-up or rather outside-in.Footnote 7 At this point we should recall that we are concentrating here on formats that numerically aggregate individual signals into a collective signal or vox populi, not just any form of online engagement. Two people sharing a political post may be an expression of online engagement but not so much an expression of 21st-century plebiscitary democracy as, say, 2 million liking such a post (cf. Jeffares Reference Jeffares2014).

Type I – inside-out and elite-focused

Besides Podemos, various other political parties have also taken new steps into the realm of Type-I votations. The European Green Party, for instance, organized an ‘open online primary’, as they called it, to select top candidates (Spitzenkandidaten) for the European parliamentary elections of 2014. Such a digital primary has an elite-forging logic to it, but leadership-challenging digital consultations can also be organized quite easily, as the earlier Podemos example testifies. As we saw, this worked practically as a party-initiated recall, organized through the Podemos website, even though it was called a ‘party referendum’ in line with more publicly resonant language.

Party- and government-initiated polls to legitimate and serve political and executive leadership have become easier and less expensive to organize on a frequent basis with present-day technology. Under pre-internet circumstances, specialized organizations were often hired for designing and conducting large-scale public polls, while nowadays virtually all of this can be done in-house. That the quality of public polling often falls back to straw-polling practices – straying from the scientific approach to representative sampling and proper authentication – is often taken for granted in these practices (Bishop Reference Bishop2005). I include these practices here to the extent that their results are expressed as representative claims in democratic discourse (cf. Saward Reference Saward2010), regarding in this subcategory the selection or deselection of political leadership. Party- or government-initiated popularity polls that are used only internally to monitor the approval rates of politicians are excluded from this overview of the new plebiscitary democracy.

A next step on this avenue (inside-out, elite-focused) is the deployment of social media and big data analytics to reveal which politician, party or authority is developing positive or negative sentiment among the public. The promise of data analytics is that vital information, also when it comes to political preferences, can be distilled from social media choices already collected in various places. Only when the aggregated choices are publicly revealed and made part of democratic discourse, which is not very often thus far, do the underlying practices fit the previous definition of the new plebiscitary democracy.Footnote 8 Until now, the results of social media and big data analytics in the political realm have tended to stay within campaign teams, using the information for covert political micro-targeting: knowing who to focus on with variable political messages from a political party or candidate in order to get better results on election day (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. Reference Zuiderveen Borgesius, Möller, Kruikjemeier, Fathaigh, Irion, Dobber, Bodo and de Vreese2018).

Type II – inside-out and issue-focused

The Type-II illustration that we started with was the NERC-initiated digital consultation of the general public that resulted in ‘Boaty McBoatface’ being pushed forward as the name for the publicly financed flagship in question. Here, the aggregated voice of the people, backed by 124,000 declarations of support, was ultimately not followed by the public authorities that had sought it. The new plebiscitary democracy is not different from older and other expressions of democracy in which the public voice is also not always or automatically followed. Yet, there are various instances where clicksultation did lead to government action. For instance, like so many other cities, Rotterdam experimented with a so-called design competition for city-enhancing ideas. Social entrepreneurs could propose ideas, the general public could express their support digitally, and the winning idea would be implemented.Footnote 9 Practices like these mobilize support digitally, through clicks of various sorts, and are often set up in a competitive fashion: ideas competing with each other for support in a win-or-lose format. In popular television language of the day: ‘you vote, you decide’.Footnote 10

If two options are specifically compared (yes or no to an idea or proposal, to a plan A or a plan B), the language of referendums is never far away, even when a referendum is formally speaking not on the roll. When Australia, between 12 September and 7 November 2017, organized a non-formal citizen survey on same-sex marriage, the Economist (2017: 49) described it plainly as ‘a plebiscite by another name’.Footnote 11 The Australian coalition government of the day had pledged to allow a private member's bill and a conscience vote in parliament on same-sex marriage if the informal plebiscite returned a majority ‘yes’, which it did (with 61.6%). This opened the way for parliamentary debate and ultimately an approved Marriage Amendment. The Australian informal plebiscite was a special exhibit of present-day plebiscitary democracy using non-digital infrastructure – technically it was a non-formal postal survey.Footnote 12 When in 2018 the European Commission organized a citizen survey on the issue of daylight saving, however, it complied again with the default of the new plebiscitary democracy and organized it as an online survey.

Digital consultations, such as the recurring internet votes on specific issues triggered by the populist Five Star Movement in Italy, are supposed to establish a direct connection between politicians and voters on an issue-by-issue basis.Footnote 13 Here, plebiscitary votations are closely associated with a populist vision of direct democracy, in opposition to the established elites and institutions of representative democracy (Franzosi et al. Reference Franzosi, Marone and Salvati2015). Looking into the Five Star Movement as well as Podemos, Paolo Gerbaudo (Reference Gerbaudo2019: 2) detects a dominant top-down and quantitative ‘plebiscitarian’ logic in their digital voting practices, overshadowing the bottom-up, qualitative, more or less deliberative digital innovations that have also been attempted.

A next step in this category is the strategic mobilization of online and social media ‘rallies’ on hot topics, organized by political actors interested in showing mass traction on such topics. An illustration is the framing of the ‘migrant caravan’ by the Trump presidency in 2018 (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Rogers and Ernst2018; Dreyfuss Reference Dreyfuss2018). Social media traction was used as vindication of presidential policy: your worries steer my policy on this issue. Consent for (re)using such digital ‘votes’ is simply taken for granted and proper authentication (is this really ‘one person, one vote’?) is not guaranteed.

The issue of voting inflation

The previous illustration prompts an issue that affects all four categories of votations. The idea of democracy assumes a demos consisting of free (non-coerced) and equal citizens (‘one person, one vote’). Theoretically, it cannot consist of (ro)bots steered to push numbers of electronic votes (likes, retweets, and so on) or fake accounts suggesting individual citizens. The problem, however, is that it is not always clear when this is happening, which may result in artificially inflated claims dressed up as the public voice (cf. Tanasoca Reference Tanasoca2019). Proper mechanisms for authentication are needed but not always present. Experiment first and improve later is quite typical of how the new plebiscitary democracy is being designed.

Another issue, also related to voting inflation, is the mobilization of click baits to give traction to ‘leading’ politicians and ‘trending’ topics in pumped-up numbers. New tech is clearly interfering here, although voting cascades and crazes are not new to democratic life.Footnote 14

Emerging formats: outside-in

Type-III and Type-IV votations share a bottom-up or, more precisely, an outside-in logic of collecting and aggregating choice-signals via regenerated plebiscitary formats. This means that the initiative lies predominantly with private and societal actors that approach the political system and its dealings from an external vantage point, attempting to force their messages into the political system, and onto it (as opposed to being consulted by system actors, which is the realm of Type-I and Type-II). The organizers of Type-III and Type-IV votations emulate, in new ways, existing formats like the voter-imposed recall, the voter-imposed initiative, the bottom-up referendum, the signature-based petition, and – again – the opinion poll (here the bottom-up version of it, commissioned by actors external to the political system).

Type III – outside-in and elite-focused

In 1842, the Harrisburg Pennsylvanian organized one of the first political polls, asking a convenience sample about their preferred candidate in the Jackson–Adams presidential race. It was a typical straw poll based on a non-random sample, which in new guises can be found as ‘vox polls’ on the websites of numerous media and other public organizations nowadays (Bishop Reference Bishop2005; Holtz-Bacha and Strömbäck Reference Holtz-Bacha and Strömbäck2012). Such instances of digital polling, using electronic convenience samples to gauge the vox populi quickly, have become virtually countless since the massive uptake of broadband internet in the early 2000s. If digital readers and website visitors are asked to rate political leaders, parties or authorities, we have an instance of a Type-III vox poll. (If they are asked to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to particular issues, we get the attributes of the Type-IV version that will be discussed later.)

A case of outside-in clicktivism (bottom-up activism using digital clicks) to challenge political leadership was played out in the Dutch city of Zutphen. In 2015, the politically selected candidate for the office of mayor (ad interim) in this town was attacked by an internet poll organized by a regional newspaper and by an e-petition organized by a worried citizen. Both were highly negative about the candidate: 95% of the participants in the internet poll agreed with the statement that this candidate ‘should stay away’; the e-petition against this candidate immediately received 2,326 signatures. Even though neither had any formal status within the nomination procedure they effectively forced the withdrawal of the candidate, who before these bouts of clicktivism had been very close to nomination.Footnote 15

An example of political leader-supporting clicktivism pushed by non-system actors was the hashtag action #ImWithHer, a digital campaign that was meant to show massive support for Hillary Clinton as candidate for the US presidential elections of 2016. The hashtag was actively pushed by celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez, Alicia Keys, Rihanna and others (Leow Reference Leow2016). #ImWithHer was not invented or hosted by the relatively centralized official Clinton campaign, which nevertheless jumped on the bandwagon quite happily, albeit not with the desired result. The 2016 Trump campaign organization showed a different, more decentralized, way of combining its own activities with external clicktivism. The combined effect in terms of aggregated supportive social media traction was significantly larger for Trump as a candidate and ultimately president-elect (van Loon Reference Loon2016; Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew2016).

Distilling from social media choices how people react to political leaders – who's trending, who's not? – is an important playing field for (new) media and (big) data and knowledge centres. When such elite-monitoring analyses are pushed outside-in by knowledge centres or media on their own initiative or commissioned by civil society organizations, they can be viewed as expressions of Type-III formats. The precondition for acknowledging these as formats of new plebiscitary democracy is, again, that the aggregated public voice must be publicly revealed and made part of democratic discourse. The difference with the elite-rating internet polls described previously is that in such polls people are explicitly asked to evaluate politicians, whereas in social media analytics evaluative questions are asked after data collection, which means that consent to use clicks for evaluative purposes is assumed rather than explicitly given (Craglia and Shanley Reference Craglia and Shanley2015). The common denominator here is the aggregative construction of a public verdict based on individually expressed evaluations, combined with and driven by an interest in mass and quantity. The more positive digital traffic there is, the more support a politician is supposed to have.

Type IV – outside-in and issue-focused

Type-IV votations share this interest in mass and quantity, working from the outside in, but are primarily focused on support for public issues. On top of the longer-existing offline version of the petition – basically an aggregated declaration of support – the phenomenon of the e-petition has spread widely. Some portals for e-petitions are privately hosted, some are publicly hosted, but as a rule e-petitions are an outside-in phenomenon. For instance, the UK government may host www.petition.parliament.uk but it does not initiate the e-petitions that appear on this site, nor does it canvass support for it. When an e-petition receives more than 10,000 signatures the UK government promises to respond to the public request voiced in it, and above 100,000 signatures a debate in parliament is considered.Footnote 16 Shortly after the Brexit referendum, more than 4.15 million people supported an e-petition posted on this website calling for a second EU referendum. The government rejected the ‘representative claim’ of the initiators, arguing that the original referendum had produced a clear and legitimate majority, which did not silence the popular call for a second referendum.Footnote 17

Beyond purpose-built e-petition websites, various other electronic platforms serve to collect and amass electronic signs of public (dis)approval. First, these may be websites built for other purposes besides signature collection that, however, also facilitate the count of likes, checks, thumbs-up or equivalent signs of support. Illustrations include the websites Decide-Madrid and Frankfurt-gestalten, which among other things track the support for different urban initiatives in quantitative terms.Footnote 18 Second, these may be social media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter and Instagram, which, in addition to many other things, facilitate the bottom-up aggregation of support for issues. This works to a large extent numerically and competitively (Nagle Reference Nagle2017; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2017). How many Facebook likes did some claim by an ideational group get? How many (re)tweets were voiced and counted on Twitter in support of some political message? How many digital photos were shared under a particular hashtag? Famous hashtag actions for an issue are #JeSuisCharlie and #Blacklivesmatter.Footnote 19 As usual in the new plebiscitary democracy ‘size matters’: the more declarations of public support aggregated, the stronger the initiators’ political claim – in this category regarding an issue of public concern – is assumed to be.Footnote 20

In 2010, the automobile club of the Netherlands, the ANWB, asked their numerous members to respond to a poll on their website related to government plans to introduce a version of road pricing. It worked as an unofficial bottom-up referendum also because it was presented as such by the car-friendly national newspaper De Telegraaf. For several days in a row it ran headlines like ‘For or against?’, ‘Numbers go through the roof’, ‘Crushing no, more than 89% against road pricing’. The government withdrew its plans, with reference to the ‘apparent’ opposition in society.

A next step in this category (onto a slippery slope, according to many, but it cannot be left out of a candid group portrait of new plebiscitary practices) is the mobilization of clicks on hot topics by political outsiders (sometimes foreign) with the intention of aggregating and amplifying political opinions that are favourable, materially or immaterially, to these actors. An example is a group working from former Yugoslavia, trying to get as many lucrative clicks from American Trump supporters, feeding them with anti-Islam content such as: ‘MOB of angry muslims ravage through US neighborhood threatening to rape women’.Footnote 21 While getting their clicks, and perhaps kicks, such disrupters create public sentiments, revealed in numbers, around public issues. Again: not an entirely new challenge to democracy, but technically facilitated in ways hitherto unseen.

Central points and caveats

The claim here, it needs to be emphasized, is not that new plebiscitary formats are successful all round. The point is that new formats of plebiscitary democracy are widely emerging and, as an interrelated complex of practices, changing democratic discourse and relations in many significant ways that are as yet under-researched and under-conceptualized. Hence, the call to develop a systematic research agenda and the attempt to understand emerging formats as interrelated empirical phenomena. The four types previously outlined can help to map the variety of forms as well as the evolving hybrids involving present-day plebiscitary democracy (see Table 1).

Table 1 maps new territory in four general directions, sketching the currently most relevant variety without pretending to be complete or exhaustive. This would indicate a grave misunderstanding of the situation. Plebiscitary democracy is a sprawling phenomenon that is still very much in development. The contemporary formats mentioned are in different stages of institutionalization. The e-petition and the internet poll, for instance, are further institutionalized than the digital primary and the electronic design contest. Some formats, like the Rotterdam City Initiative contest, were discontinued after a few years of practice and are exchanged for other experiments. Compared to the new plebiscitary formats, the older underlying formats – initiative, referendum, recall, primary, petition, public poll (pre-internet) – are clearly further hardened and codified in ‘textbook varieties’ (Altman Reference Altman2011, Reference Altman2017; Cronin Reference Cronin1989). The developing formats of the new plebiscitary democracy are not yet in that stage of institutionalization and codification. The emergent, varied and sprawling nature of the phenomenon will complicate but should not stop the exploration and documentation of the phenomenon.

It is clear that the developing plebiscitary democracy comes in many shapes and forms. Yet, under the many expressions common traits can be detected, most prominently the centralization of individual choice signals, which in one way or another are aggregated into a collective vote or public voice. The related message, always implicit, sometimes explicit, is that everyone can rate things and people in the public realm – Andrew Keen (Reference Keen2007) called this the ‘cult of the amateur’ – and that the resulting aggregated ratings should be taken seriously in the formation and translation of public opinion (cf. Harari Reference Harari2017: 271; Susskind Reference Susskind2018: 139). The classic expression ‘vox populi, vox dei’, rendering the voice of the people sacrosanct, is refurbished and writ large in the new plebiscitary democracy.

New plebiscitary mechanisms are often electronically enhanced, which makes this a prominent instrumental feature.Footnote 22 More central to its character, however, is the fact that the new votations tend to result in binary public verdicts (for/against, yes/no) wherein a bigger-the-better logic prevails. Claims with many clicks, likes and checks behind them are assumed to be the more legitimate claims, able also to compete with the representative claims of political parties and ideational groups. Numbers of followers make the difference in a democratic ethos that is fiercely majoritarian and competitive. Jill Lepore (Reference Lepore2018) argues that a ‘democracy of numbers’, as she calls it, is deeply American, but as we have seen a new democracy of numbers is coming to the fore in other places as well.Footnote 23

New plebiscitary practices tend to expand or radicalize longer-existing formats with new means. The centuries-old petition, for instance, is being echoed and blown up in numerous present-day expressions of clicktivism. In addition, new ways of voting are often likened to or presented as a ‘referendum’, even when technically speaking a party recall (see the Podemos example) or an internet survey (see the ANWB example) would be a more accurate frame of reference. The use of referendum language far beyond its formal niche is a remarkable by-product of the new plebiscitary democracy. When the US Congressional elections of 2018 are dubbed a ‘referendum’ on the Trump presidency, or when the European Parliament elections of 2019 are framed as a ‘referendum’ on the borderless Europe of the elites versus the Europe of the people, we see plebiscitary discourse hooking onto the realm of electoral democracy.

As Figure 1 suggests, the new plebiscitary democracy develops to some extent connected with, and to some extent detached from, established electoral democracy. Clicktivism of the #JeSuisCharlie type, for instance, has a clear political message and meaning but does not primarily appeal to representative politics. To a considerable extent, however, plebiscitary democracy is also entangled with the realm of established electoral democracy.Footnote 24 Take the digital votations that are used to (de)select political leaders, or to select a winning ‘city initiative’ to be funded by a municipality. Or look at some of the other earlier exhibits: the Australian postal survey that opened the door to a private member's bill on same-sex marriage, and the informal ‘referendum’ organized by the Dutch automobile club that directly affected governmental decision-making.

What we have here is more refined than a simple zero-sum game: what plebiscitary democracy wins is not necessarily lost by electoral democracy, or vice versa. To better understand the patterns of interactions, we need to delve deeper into them. In the next section, I will demarcate the interactions to investigate more deeply. There, I also discuss the relationship between present-day plebiscitary and deliberative democracy: in essence competing views on how democracy should be extended. The aggregative, majoritarian and competitive spirit that inspires plebiscitary democracy runs counter in many ways to the integrative, consensual and transformative spirit that infuses deliberative democracy (Gerbaudo Reference Gerbaudo2019: 3; Hendriks Reference Hendriks2019: 453).

Towards a research agenda

The argument advanced in this article is that we need to understand the new plebiscitary democracy better than we presently do, not only its inherent dynamics but also its relation to the established systems of electoral democracy and the prominent alternative of deliberative democracy. For this purpose, Figure 1 is transformed into an analytical scheme, with elements and relationships to be prioritized in research – marked A, B and C in Figure 2. I readily admit that concentrating on empirical issues related to the new plebiscitary democracy as a political phenomenon is a choice. I do not deny that there are wider-ranging normative and societal questions to ask, which deserve separate treatment.Footnote 25

Figure 2. Taking the New Plebiscitary Democracy on: Priority Research Areas

Plebiscitary additions: varieties, drivers, implications

The analytical triangle of Figure 2 has three corners pointing to, first, an established system of electoral democracy; second, a comparatively advanced set of deliberative additions that have been promoted widely since roughly the 1990s; and third, a comparatively new set of plebiscitary additions that have accelerated strongly in the 2010s. This last, the bottom-left corner, is thus far least documented by empirical research. This may be understandable from a historical perspective, but in view of 21st-century developments this needs changing urgently. The exploration of plebiscitary democracy developments in previous sections prompt a number of follow-up questions, of which the following take precedence.

A1: What are the enduring expressions of 21st-century plebiscitary democracy?

A2: What are the main drivers behind these expressions?

A3: What are the implications for citizen participation and civic culture?

Expressions

First, we need to track and trace which of the developing formats of 21st-century plebiscitary democracy, summarized in Table 1, develop into more or less durable expressions. Of the many new formats that are tried and tested at some point in time, a smaller set of formats is expected to become institutionalized and passed on. Some of these formats may develop within the confines of the four ideal-typical categories distinguished above; a strong candidate is, for instance, the issue-supporting e-petition, mobilizing outside-in digital support for particular causes. Some other formats may cross boundaries: we could think of the new-style political party website that is used for leadership votations as well as issue-related vox polls. When the deliberative turn was proclaimed in the 1990s it took years of extensive research to reach a significant level of consensus on the main empirical formats of deliberative democracy (Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Niemeyer, Neblo, Steenbergen and Steiner2010; Gastil and Levine Reference Gastil and Levine2005). A similar trajectory could be expected for the new plebiscitary democracy. To provoke future research, it is postulated that inside-out formats developed by governments and political actors will increasingly be designed to capture or placate outside-in pressures for votations, which will in turn trigger new and other outside-in formats. Additionally, it is postulated that plebiscitary formats with staying power will be leader focused and issue focused, as both reflect more general tendencies of information-age societies to rate people as well as things (cf. Hill Reference Hill2013; Keen Reference Keen2007; Nagle Reference Nagle2017; Susskind Reference Susskind2018).

Drivers

Second, we should understand the driving (f)actors behind the new formats of voting better than we presently do. In addition to technological there are cultural and related political drivers to consider. The turn to deliberative democracy in the late 20th century was seen to be related to the coming of age of a new social and political culture, which had pushed values of active participation, open communication and self-expression since the late 1960s (cf. Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1990). Likewise, it seems that the new plebiscitary democracy is pushed by the more recent rise of populism – favouring more ‘hardball’, aggregative and majoritarian practices (cf. Kriesi Reference Kriesi2014; Mounk Reference Mounk2018; Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Müller Reference Müller2016). If populism is about who should govern (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019: 248), then the new plebiscitary democracy seems to fill in how this can be done: with renewed and radicalized variants of plebiscites. Relatedly, it seems quite plausible that new plebiscitary instruments are turned and appealed to as a response to a real or perceived crisis of established parties and electoral politics (cf. Bardi et al. Reference Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel2014; van Biezen et al. Reference Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012). The technological push behind the new plebiscitary democracy is evident, but at the same time insufficiently understood. New digital and social media applications, connecting user-friendly smart devices to broadband internet, seem to push competitive, vote-counting practices (Halupka Reference Halupka2014; Harari Reference Harari2017: 394, 435 ff; Hill Reference Hill2013). But what are the underlying mechanisms and connections, and who are the actors and organizations that actually forge the technological push?

Implications

Focusing on the empirical-political consequences of the new plebiscitary democracy, as we do here, the consequences for civic culture and democratic citizenship are highly urgent.Footnote 26 One of the obvious questions here is how and to what extent new plebiscitary practices help or hinder different types and groups of citizens in a political sense. Studies of political clicktivism suggest that its participants display a rather different profile than participants in deliberative-democracy practices: on average less highly educated, less interested in detailed policy-oriented meetings and more interested in quick messaging via mass media (Halupka Reference Halupka2014; Nagle Reference Nagle2017; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2017). While this may be true for particular expressions, there is reason to believe that this does not work exactly the same for all expressions of plebiscitary democracy. For instance, the initiators of and the participants in the e-petition demanding a second referendum on Brexit, another previous example, displayed a rather different profile from the ones behind the #LockHerUp Twitter rally.Footnote 27 A more refined picture of what plebiscitary democracy in its various guises does with citizens and participation is thus needed. Another obvious question here is how and to what extent new plebiscitary practices push a shift from pluralism to populism (the reverse of what is asked under question A2).

Plebiscitary additions and established electoral democracy

While the interplay between deliberative democracy and established electoral democracy (the continuous line in Figure 2) has been problematized and investigated for many years (e.g. Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000; Gastil and Levine Reference Gastil and Levine2005; Setälä Reference Setälä2017), a lot of catching up needs to be done for the connection between the new plebiscitary democracy and the established system of electoral democracy. As plebiscitary practices are basically more majoritarian in their setup, it would be pertinent to compare their uptake in majoritarian (winner-take-all) versus proportionally representative (PR) electoral systems, besides looking at how they impact on electoral democracy's central institutions and political culture:

B1: To what extent and in which way does the uptake of 21st-century plebiscitary formats differ in majoritarian versus PR electoral systems?

B2: What are its implications for electoral democracy's central institutions?

B3: What are its implications for political discourse and governing style?

Uptake

It could be argued that winner-take-all (district-based majority or plurality) systems present a more fertile breeding ground and more conducive political opportunity structure for 21st-century plebiscitary formats than PR electoral systems. ‘Majoritarian institutions breed plebiscitary votations’ at face value seems plausible, but this needs to be reviewed more closely. A rival hypothesis would be that PR electoral systems, because of their diluted compromises between multiparty elites, trigger plebiscitary reactions that follow extra-institutional pathways (cf. Caramani and Mény Reference Caramani and Mény2005). If we look at the underlying, longer-existing formats of plebiscitary democracy, we do not see one clear pattern for all formats. Primaries and recalls have spread most prominently in the US two-party system. Public polling (of both political personae and issues) also developed earlier and stronger in this context – but not uniquely there. Referendum practices have developed strongly under PR circumstances in Switzerland, Italy and more recently subnational Germany, while the majoritarian electoral systems of France and the UK have also seen referendums – albeit of different kinds (Altman Reference Altman2011; Qvortrup Reference Qvortrup2018). By the same token, we should expect the emerging formats of the new plebiscitary democracy to follow not one but various institutional pathways. More specifically, we should expect majoritarian and PR systems to both trigger elite-focused and issue-focused votations, outside-in as well as inside-out – following different paths of action and reaction, yet to be understood.

Impact on central institutions

New political tools and applications potentially impact positions and resources of central institutions in electoral democracy such as executive offices, representative bodies and political parties. Institutional and network analyses should reveal whether and how this is the case, first and foremost for the countervailing powers of executive and representative institutions. Both sides can organize inside-out votations, and both can be the target of outside-in votations, but differences are likely to exist. The expectation is that representative bodies (parliaments, regional and local councils) have more leeway to direct or redirect the vox populi towards the executive (governing boards and office-holders) than the other way around. The executive branch seems more challenged, potentially disrupted, by votations targeting specific issues and politicians, further reducing governing discretion. Particularly interesting to trace is how new populist politicians position themselves in the matrix of plebiscitary pressures and possibilities (see Table 1) when taking up executive responsibilities, and how this differs from more traditional governing elites. Not only in executive office, but in the political realm in general, the strategic positioning of populist parties is worth following. It could be argued that the new plebiscitary democracy gives them a strategic advantage vis-à-vis establishment parties as this ‘medium’ seems closest to their ‘message’ (cf. Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Müller Reference Müller2016). History, however, teaches us to not rule out surprises. Catholic conservatives in 19th-century Switzerland, for instance, were originally far removed from the referendum instrument, but nevertheless discovered and captured its strategic use (Kriesi and Trechsel Reference Kriesi and Trechsel2008).

Political discourse and style

An important question is how political debate (including claim-making and rhetoric) and governing style (including manner of communication and interaction) change in connection with new plebiscitary practices. Do we see the discourse surrounding plebiscitary votations – with its strong focus on mass, traction and numbers – echoed or reframed in the political (speech) acts that emanate from the benches in parliaments and local and regional councils? Do we see governments develop new ways of dealing with the general public – proactively or reactively tackling the public voice that is constructed around issues or people? Cultural and more specific discourse analyses should reveal whether and how this is the case. We already asked if and how plebiscitary practices spread differently in majoritarian (winner-take-all) versus non-majoritarian (consensual) democracies (question B1). Here, we can add: Do they touch these systems differently on a cultural level? The proposition – sharp on purpose – is that cultural disturbance following the emergence of new plebiscitary practices are more intense in consensus democracies than in majoritarian systems. The clash with consensus democracy's focus on integrative elite deliberation and its fear for mass politics by the numbers is comparatively more intensive, and could be expected to inspire repulsive discourse and aversive action sooner and more strongly (Hendriks Reference Hendriks2009).Footnote 28

Deliberative and plebiscitary additions

The various formats of deliberative democracy – from mini-publics to consensus conferences and everything in between – have been extensively described; this pertains also to how deliberation may clash with and how it can contribute to established electoral democracy (cf. Beauvais and Warren Reference Beauvais and Warren2019; Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000; Hendriks and Kay Reference Hendriks and Kay2019; Setälä Reference Setälä2017). The relationship between deliberative democracy and 21st-century plebiscitary democracy, however, still needs to be defined properly. The two can be viewed as rival democratic innovations, but also as formats that to some extent may be combined to contribute to the democratic process. This prompts two types of questions:

C1: What are the comparative merits – advantages and disadvantages – of new plebiscitary versus deliberative formats?

C2: What is the feasible space for combinations – for connecting new plebiscitary and deliberative formats?

Comparative merits

Comparative (dis)advantages need to be analysed, first of all, at the level of internal qualities. What is it that new plebiscitary formats, because of their design characteristics, do better or worse than deliberative formats? As they involve different technologies and organizational models, they should be expected to have different sorts of leverage for different purposes. Frank Hendriks (Reference Hendriks and Kay2019) has compared different forms of mobilized and randomized deliberation with the digital quasi-referendum on four quality criteria: equality, participation, deliberation and concretization. By way of its design, the quasi-referendum can reach more participants, but in terms of equal opportunities for representation randomized deliberation generally has better credentials. Such a comparative analysis should be broadened to include other versions of 21st-century plebiscitary democracy (the e-petition, the digital primary, etc., outlined in Figure 2, and to be detailed from question A1). The analysis should be open to possible additional qualities, such as channelling collective self-expression (designed into e-petitions, hashtag-clicktivism and the like), or empathy for the other side of an argument (not habitually designed into these formats). In addition, we should compare the external effects of different formats in relation to established electoral democracy. Plebiscitary formats have a specific way of working with or against representative politics. Like deliberative democracy formats, plebiscitary versions start with criticism of ‘thin’ electoral democracy, which would be inferior to what alternative methods can offer. While deliberative formats can claim deeper and richer collective reflection (Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Niemeyer, Neblo, Steenbergen and Steiner2010), plebiscitary formats may claim popular support in larger numbers. In a comparative analysis of merits, the question should not only be ‘Is it true?’ (do they deliver the quality and support levels that they claim), but also ‘Does it matter?’ (to what extent and how are they able to change courses of action, politics and policies in the real world).

Space for combinations

New plebiscitary and deliberative formats display different democratic logics, which are in many ways at odds with each other. Does that mean the twain shall never meet? Not necessarily, as some empirical instances of deliberative-plebiscitary mixing show. The Irish mini-public on abortion was mainly a deliberative and integrative affair, but also included moments of aggregation and counting, most prominently in the final referendum that confirmed the advice that the mini-public had produced (Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Suiter and Harris2019). The ‘citizen initiative review’ is another hybrid, in which a deliberative mini-public is asked to look into and advise on the options put forward by citizen initiative, prior to massive, dichotomous voting (Gastil et al. Reference Gastil, Johnson, Han and Rountree2017). In theory, various new combinations of digital voting and electronic deliberation could be envisioned (Susskind Reference Susskind2018: 212–213). For design thinking in the realm of democratic innovation this is promising land to explore. For the empirical research agenda advocated here, the relevant questions are where, when and how such new combinations appear. What appears to be the feasible space for such combinations? Does type or scale of public governance constrain the appearance of mixed models? In general, it may be expected that keeping deliberative and plebiscitary formats apart is the default position and that mixing them requires special circumstances. To put it differently, ‘mixophobia’ (fear of pollution) is the primary pattern to be expected in the relation between new plebiscitary and deliberative practices, and ‘heterophilia’ (love for the different) is the exception requiring special triggers, which need to be pinpointed. As an alternative proposition it is suggested that democratic innovators, notwithstanding possible inhibitions, are ultimately forced to respond to the heterogeneous needs of users and fields on application.

Concluding remarks: taking the new plebiscitary democracy on

The central conclusion of this article is quite simply that a new plebiscitary democracy is developing, with various new formats building and varying on longer-existing formats, and that this presents an urgent development that warrants more systematic research than is presently available. The article develops a matrix of central expressions of the new plebiscitary democracy (summarized in Table 1) and priority areas for research into the phenomenon itself and its relationship with established electoral democracy, and with deliberative democracy as an alternative source of democratic transformation (Figure 2).

Plebiscitary transformations partly overlap with deliberative ones and with established electoral democracy. The Venn diagram with three overlapping spheres (Figure 1) could be compared to the one used by Russell Dalton, Bruce Cain and Susan Scarrow (Reference Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2003: 252–256) to summarize their seminal research of democratic transformations in 18 OECD countries between 1960 and 2000. While the sphere of established electoral democracy remained about as important, the spheres of ‘direct democracy’ and ‘advocacy democracy’ – as Dalton et al. framed the two main alternatives to established electoral democracy – grew significantly in the last four decades of the 20th century. Considering 21st-century developments in democratic practice, the two main alternatives to electoral democracy are reframed as plebiscitary democracy and deliberative democracy. As the ‘turn’ to the latter has been documented extensively (cf. Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Niemeyer, Neblo, Steenbergen and Steiner2010; Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000), the objective here was to unravel developments in the sphere of plebiscitary democracy, building on the formal expressions (referendum, initiative, recall and so on) that Dalton et al. classify as direct democracy. We saw a multitude of new 21st-century plebiscitary practices emerge on a substratum of older plebiscitary formats. Echoing the words of Dalton et al. (Reference Dalton, Cain, Scarrow, Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2003: 255), it is possible to sketch only in ‘imprecise terms’ the growing significance of the circle of plebiscitary additions. Admittedly, the evidence presented in previous sections is mainly qualitative. But as quantitative indicators for the prevalence of formal referendums have been developed (cf. Altman Reference Altman2011; Qvortrup Reference Qvortrup2018), such indicators can also be developed for the (often digital) quasi-referendums of the new plebiscitary democracy, although this will need time.Footnote 29

Various objections to this account can be envisioned. The first and potentially most damaging objection would be that there is no such thing as a new plebiscitary democracy, or at least not a new plebiscitary democracy. It is a deep truth that in the world of democracy almost nothing is unrelated to something old. As we have seen, new plebiscitary formats reinvent and radicalize longer-existing formats. They do so in a period of revolutionary technological change – a massive uptake of broadband internet, an explosion of smart devices and interactive social media – which takes plebiscitary formats to a next stage and level. While technological innovations make new ways of direct voting increasingly possible, related shifts in popular culture make them increasingly popular. Since the turn of the century interactive television with popular televoting formats has strongly converged with internet and social networking (Bignell Reference Bignell2012: 283–293). Countless new and old media have followed suit, which has contributed to the uptake and popularity of practices such as the ones described here (Ross Reference Ross2008). At this point, a small thought experiment is suggested: take the matrix of new plebiscitary options in mind (Table 1), follow the political news for a month or so, and then ask yourself whether the new plebiscitary democracy is any less real in an empirical sense than the turn to deliberative democracy which was proclaimed earlier.

A second objection is to say that new plebiscitary practices may be coming to the fore, but should not be taken seriously, accredited with academic research, compared with consciously designed democratic innovations backed up by refined political theory like deliberative-democracy theory. Are new practices of voting not often ill-designed, flimsy, quick-and-dirty, and potentially dangerous? New plebiscitary votations may be popular, but doesn't this make them vulnerable to populism, to democratic illiberalism? Even if we assumed that previous questions could already be answered with an unequivocal yes for all new plebiscitary practices, then the case for doing more research into the phenomenon would be fortified, not weakened. Even though there are dubious practices that need to be exposed, not all the new plebiscitary voting practices can be dismissed so easily. Guilty by association is not fair grounds for sentencing, and could be challenged with reason. If the European Green Party organizes an ‘OpenOnline Primary’ it is not automatically on the same page as the Italian Five Star Movement when it organizes some e-referendum. And if such parties or other organizations are experimenting with digital plebiscites, then the relation with democratic values needs to be investigated properly, not a priori assumed to be negative.Footnote 30 In general, the democratic claim associated with new plebiscitary practices must not be taken for granted, but neither can it be dismissed from the outset.

A third objection would be to argue that the new plebiscitary democracy is indeed real and to be investigated seriously, but not described with enough detail in this article. Surely, specific exhibits of the new plebiscitary democracy (the Podemos digital referendum, for instance, or the EU online survey) can be developed into detailed individual case studies. But this was not the focus nor the objective here. Specification of depth and singularity has been deliberately sacrificed here to revealing empirical breadth and interconnectedness as well as typological variety of the phenomenon. From an explorative perspective, a wide-angle group portrait was deliberately chosen over close-up individual portraits. More fundamental than the details of individual cases, it was argued, are the general types of developing formats emerging on a substratum of longer-existing methods. The Podemos digital referendum, for instance, is put in a wider perspective here, exhibiting how older plebiscitary expressions are being reinvented with 21st-century tools and terms. Undoubtedly, more can be said about such a case when developed from a more hermeneutical perspective. In the research agenda that was set out, such research is actively promoted.

The proposed research agenda is open-ended. It defines priority areas for research, and formulates urgent research questions that can be elaborated on, as will be required for an emergent and dynamic phenomenon such as the new plebiscitary democracy.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Alex Ingrams, Haye Hazenberg, Ira van Keulen, Ammar Maleki, Mariangela Veikou, the anonymous reviewers and the editors of this journal for useful comments on earlier versions of this article