How are we to understand the relationship between capitalism and democracy? This issue is on the public agenda again. ‘Is Capitalism a Threat to Democracy?’ asks an article in The New Yorker. ‘Are Capitalism and Democracy Compatible?’ asks the Huffington Post. Social scientists are also taking up the question anew, with some suggesting that the dynamics of capitalism have overwhelmed democracy, while others argue that democratic polities retain control over capitalist economies (cf. Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019; Streeck Reference Streeck2017).

Renewed interest in such issues is not surprising. We are living through an era of profound turbulence in modern capitalism and democratic politics. Rising levels of income inequality have called into question the capacity of capitalism to deliver prosperity for all, a technological revolution threatens vast social dislocation and global trading regimes are falling apart. In the political arena, support for established parties is declining. New parties with dubious commitments to democratic values are gaining votes and there is doubt about whether governments presiding over fragmented polities can cope with contemporary economic challenges. Since the capacity of governments to master such challenges turns in large measure on relations between capitalism and democracy, this is a propitious moment to revisit that classic relationship.

What is at stake? For some, the issue has been about the survival of capitalism or democracy. Do these two systems tend to undermine each other? That is a reasonable question since it is not obvious that a system based on economic inequality is compatible with another built on political equality. In less apocalyptic terms, the issue is about the balance of influence between the forces driving capitalism forward: the owners and managers of capital, on the one hand, and democratic governments seen as the agents of a popular will, on the other. Here two related outcomes are at stake: the prosperity of a nation and the distribution of well-being within it. Both depend on the practices of capitalist firms and the steps taken by governments to mitigate their adverse effects. Where the requisites for successful capitalism are ignored, national prosperity suffers but, if the adverse effects of capitalism go unaddressed, the distribution of well-being will be skewed.

In his famous treatise on the development of capitalism, Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1944) identified the problem as one of sustaining a double movement. On the one hand, states make robust capitalism possible by removing barriers to competition and turning land, labour and capital into commodities. On the other hand, unless states ensure that market relations are embedded within a superordinate set of social relations, they court political rebellions that threaten the survival of democracy. The emphasis of this article is on that distributive question – namely, on how the balance of influence between capitalism and democracy impinges on how well citizens are protected from the adverse effects of capitalism.

I will argue that, in order to understand this balance of influence, we need to think about the relationship between capitalism and democracy in terms that go beyond classical discussions with a view to appreciating how that relationship changes over time. For this purpose, I employ the concept of growth regimes to describe changes in capitalism and the concept of representation regimes to capture changes in democracy. My argument is that changes in representation regimes, closely tied to shifting cleavage structures in electoral politics, alter the balance of influence between capitalism and democracy, with consequences for both the trajectory of public policy and distributive outcomes. I illustrate this argument with an account of how the systems of capitalism and democracy have changed in the developed economies over the years since the Second World War.

Classical views

There is a long and distinguished literature on the relationship between capitalism and democracy whose outlines I sketch only briefly. As suffrage expanded across 19th-century Europe, bringing with it the prospect of mass democracy, many early observers regarded democracy as a threat to capitalism – a view prominent among British opponents of extending the franchise. In the memorable words of Lord Salisbury, giving the vote to ordinary people might mean ‘that the rich shall pay all the taxes, and the poor shall make all the laws’ – a concern shared in less flamboyant terms by liberals such as John Stuart Mill (Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017: 111). From the other side of the political spectrum, Karl Marx predicted that the extension of the suffrage in 19th-century France might intensify class conflict, putting the proletariat in a position to abolish capitalism, a view embraced by some of his followers half a century later (Kautsky Reference Kautsky1923; Marx Reference Marx1871).

Others have argued that capitalism is a threat to democracy. Their premise is that capitalism translates economic power into levels of political power sufficient to subvert democracy. Capitalists are said to derive such power from the advantages that money or social standing confer on candidates for political office and from their capacities to manipulate public opinion. Lenin held such views and Gramsci articulated them in more sophisticated terms, paving the way for a sociology of power that outlines how business interests can manage the public agenda (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971; Lenin, Reference Lenin1917; Lukes Reference Lukes1974; Mills Reference Mills1956). In the terms of an old British saying, the result is that ‘governments may come and go, but the conservatives are always in power’.

By contrast, other scholars have argued that capitalism and democracy are not only compatible but largely symbiotic. Some emphasize the contribution of democratic institutions to capitalist development, noting that the success of capitalism depends on secure property rights whose maintenance requires a state dedicated to the rule of law. But this poses a ‘fundamental political dilemma’ for capitalism because ‘a state strong enough to protect private markets is strong enough to confiscate the wealth of its citizens’ (Weingast Reference Weingast1995: 24). Hence, capitalists need not only a strong state, but also a credible commitment that this state will respect their property rights, which democratic institutions are said to supply because they place control over the state in the hands of representatives of these property owners. In that vein, Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012: 96) argue that successful capitalist development depends on ‘inclusive economic institutions’ that ensure the security of private property, the rule of law and the freedom to contract ‘forged on foundations laid by inclusive political institutions, which make power broadly distributed in society and constrain its arbitrary exercise’.

Lindblom (Reference Lindblom1980) offers a parallel analysis to explain why the institutional conjunction of democracy and capitalism confers structural power on capitalists (see also Block Reference Block1987). In order to secure re-election, democratic politicians must preside over prosperity, which depends under capitalism on the investments that capitalists will make only if they have confidence in the environment for business. Hence, he argues, democratic governments will avoid steps that damage such confidence. Hayek (Reference Hayek1944) argues for symbiosis on different grounds. He suggests that, by dispersing economic power among the owners of private property, capitalism gives the citizenry a basis for defending democracy against the threats that central planners might otherwise pose to it.

Towards an alternative perspective

This classic literature about the relationship between capitalism and democracy is illuminating, but it suffers from two limitations. First, much of the literature focuses on whether the two systems can co-exist, and there is more at stake here than their survival. As Iversen (Reference Iversen and Goodin2011) has noted, the tensions between capitalism and democracy also affect levels of national prosperity and the distribution of well-being, and we need to know more about how the relationship affects such outcomes.

Second, many analyses treat capitalism and democracy as fixed sets of core institutions that do not vary much over time. These structural analyses are insightful. However, the operation of each system depends not only on core institutions but also on ancillary features, such as the corporate strategies that organize work and the political conditions driving electoral outcomes, and these features change over time. As Sewell (Reference Sewell2008) has observed, capitalism is notoriously sinuous: the industrial capitalism of the 19th century was very different from the knowledge economy of the 21st century. The operation of democracy also shifts over time, as new social divisions alter the nature of electoral competition and novel political ideologies work their way into modes of state intervention. Developments such as these alter the operations of capitalism and democracy over time and hence the relationship between them. As capitalism evolves, it throws up new challenges for democracy; as democracy evolves, its capacity to cope with those challenges changes.

Therefore, if we want to understand the relationship between capitalism and democracy and its consequences for social well-being, we need to appreciate how capitalism and democracy change over time. That calls for a more historical analysis and for categories capable of capturing developments with significant effects on the relationship between these two systems. For this purpose, I will focus on what I term the ‘growth regimes’ and ‘representation regimes’ prevalent at specific periods in time. Growth regimes inflect the operation of capitalism, while representation regimes describe historically specific features of democracy.

Growth regimes

Notable attempts have been made to capture how capitalism changes over time, albeit without focusing on the relationship with democracy. Some highlight the roles of finance and the state (Gerschenkron Reference Gerschenkron1962; Hilferding Reference Hilferding2019; Lenin Reference Lenin1917; Shonfield Reference Shonfield1969); others stress changes in workplace relations or regimes of accumulation (Boyer Reference Boyer1990; Braverman Reference Braverman1974), while recent approaches emphasize variations in macroeconomic or social policy (Baccaro and Pontusson Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016; Hassel and Palier Reference Hassel and Palier2021). My concept of growth regimes is informed by these analyses but has some distinctive features.

As I construe it, a growth regime refers to the ensemble of institutionalized practices central to the process whereby a country secures prosperity. At the heart of these regimes are the practices established by two core actors: the firms that superintend production in a capitalist economy and the governments whose policies bear on that production in manifold ways. The practices of firms are central, not only because firms are the principal productive units in a capitalist economy – on which investment, innovation and national levels of output depend – but also because these practices affect the distribution of well-being in society. The relevant dimensions of firm strategy extend from how labour is managed, capital raised and value produced, to how the overall goals of firms are defined and pursued in the multiple arenas within which they operate (cf. Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001).

Moreover, although there are some basic commonalities across space and time in how capitalist firms operate, encompassing the pursuit of profit and the use of hierarchies to manage transactions, the strategies and corresponding practices of firms change substantially over time (cf. Chandler Reference Chandler1993; Williamson Reference Williamson1983). Many of those changes come in response to technological developments offering new modes of production or marketing, while others respond to developments in the international economy that alter the markets and production sites available to companies. However, shifts in firm practices can also be inspired by changes in their institutional environment, notably in the markets where firms secure capital and labour (Streeck Reference Streeck, Hollingsworth and Boyer1997).

In that context governments matter. The policy regimes devised by governments are central to establishing the institutional environment in which firms operate. Industrial relations regimes affect the terms on which firms can recruit or utilize labour. Educational and training policies condition the supply of qualified labour. Through support for research and development and regimes of intellectual property rights, governments condition how firms access and use technology. Financial regulations influence the terms on which they can access capital. The trade regimes and competition policies of governments affect the competitive environment facing firms, and myriad regulations protecting consumers and the environment influence what firms can produce.

As a result, public policies are just as central to the complexion of a growth regime as firm strategies are; and one of the defining features of a growth regime is the presence of policies broadly supportive of prevailing firm strategies. Even in the most coherent regime, of course, not every public policy serves the interests of firms. But growth regimes, as I define them, are marked by a certain degree of complementarity between prevailing public policies and firm practices. Indeed, although these policies and practices are always in flux at the margins, we can say that there is movement from one growth regime to another when firms and governments shift in tandem towards new sets of mutually reinforcing practices.

As I have noted, growth regimes can be judged both by the level of prosperity they support and by how they distribute its fruits, and movement between growth regimes is consequential in the first instance because the practices of firms affect both dimensions of well-being. At a macro level, they condition the levels of investment on which rates of productivity and growth depend as well as the share of national product going to wages and the geographic location of jobs. At the micro level, firm practices affect the wages and benefits, employment security and working conditions available to various types of workers. But democratic governments also condition these outcomes, both directly through their policies and indirectly through the impact of these policies on firm strategies. Accordingly, we also need to consider how democracy changes over time. For this purpose, I turn to the concept of representation regimes.

Representation regimes

Two issues are central to contemporary debates about the relationship between capitalism and democracy. The first, normally given the most attention, is: how much control do democratic governments exert over capitalist economies? But, since democracies are representative systems designed to speak for a popular will, an equally important issue is: on whose behalf do governments exercise that control? These are ultimately questions about the nature and effectiveness of democratic representation, namely, whose voices are heard and with what force over the allocation of resources?

To address these issues, I use the concept of a representation regime. These regimes operate through two arenas: the realm of electoral politics, where political parties are the principal actors, and the realm of producer group politics, where organizations speaking for various segments of labour and capital are the main actors. The latter includes industrial relations systems that give the representatives of labour and capital roles in the determination of wages and working conditions.

Issues of representation are the subject of a large and illuminating literature whose nuances lie beyond the scope of this article. Broadly speaking, however, most analyses of representation in the electoral arena focus on variation across nations or over relatively short periods of time with an emphasis on (1) the impact of institutions, such as electoral rules and constitutional structures; (2) the role of median voters; or (3) the partisan composition of governments, where the electoral strength of social democracy is especially germane. In the arena of producer group politics, the emphasis is usually on institutions for interest intermediation (for reviews, see Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Keane and Merkel2011; Buhlmann and Fivaz Reference Buhlmann and Fivaz2018).

Since the focus of this analysis is on variation in representation over relatively long periods of time, however, some features of the electoral arena that may be important for explaining short-term or cross-national variation recede in importance, while others come to the fore. For instance, constitutions and electoral rules are often invariant over the decades examined here. Median voter models that ascribe electoral outcomes to the views of decisive voters positioned in the middle of a distribution of opinion retain their formal force but often fail to say enough about how the concerns of these voters change over time. The voice of the middle class is always important, but we need to know why it speaks in different tones at different times and places.

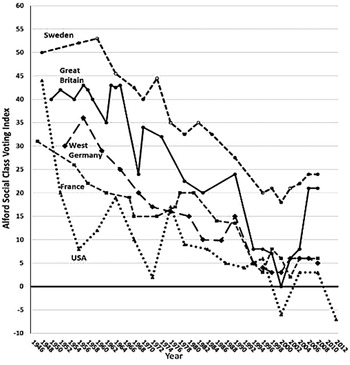

Even accounts associating representation with the partisan complexion of governing parties provide only part of the story. Those accounts can often explain movements in policy over the short term. But even more consequential for whose voices are heard over the long term are changes in the programmes of political parties, which partisan alternation in government rarely explains. Looking across decades, the striking phenomenon is how often mainstream political parties have moved in tandem, especially on issues of how to manage a capitalist economy (Green-Pedersen and Walgrave Reference Green-Pedersen and Walgrave2014 and Figure 1). Many scholars have noted the convergence of mainstream party platforms towards neoliberal policies during the 1980s and 1990s (e.g. Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019; Mair Reference Mair2013), but the 1950s and 1960s saw a parallel convergence to the left – so pronounced that the British policies of that era were commonly termed ‘Butskellist’ after the names of contending Chancellors of the Exchequer (Brittan Reference Brittan1971).

Figure 1. Support for ‘Free Markets’ in the Platforms of European Political Parties, 1957–2015

Source: Manifesto Project Database https://manifesto–project.wzb.eu/.

Note: Party positions on the ‘free market economy’ index of Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe2011) indicating the prevalence in party platforms of support for a free market economy and market incentives as opposed to more direct government control of the economy, nationalization or other Marxist goals. Higher values indicate more support for free market positions. Countries include: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

These observations suggest that over the long term ‘whose voices are heeded’ turns not so much on changes in the partisan hue of government, as on shifts in the terms of political contestation – that is to say, on changes in the issues most salient to electoral competition and how they are framed. Given the centripetal dynamics of mainstream partisan competition, any winning coalition is likely to address the issues at the heart of electoral competition, albeit with a partisan tint (Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Green-Pedersen and Mortensen2020; Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2007). As scholars of agenda-setting since Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960) have noted, what the parties are fighting over can matter more to the subsequent course of policy than which party wins, and the voice of a social group becomes louder when the issues of concern to it rise to the top of the political agenda.

Therefore, the question becomes, why do some issues rise to prominence on that agenda, while others remain on its margins? I suggest that two factors are most central to that. The first are major real-world events (see also Green-Pedersen and Walgrave Reference Green-Pedersen and Walgrave2014). For the economic issues of interest here, the most relevant events are likely to be episodes of recession or inflation with widespread adverse consequences. Parties competing for office must react to such events, although their responses will be inflected by prevailing doctrines about how to manage them. All parties competing in the 1940s and 1950s, for instance, were influenced by the consequences of the Great Depression of the 1930s, much as those seeking office after the economic crisis of the 1970s had to address issues of inflation and economic stagnation.

The second factor driving the prominence of issues on the political agenda is the prevailing political cleavage structure. The concept of political cleavages has a distinguished history (Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Mackie and Valen1992; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). Following standard practice, I use the term to refer to divisions of outlook or interest between large sociodemographic groups, often associated with collective identities, that lead to systematic differences in voting behaviour. Because they reflect major lines of social conflict, the presence of specific cleavages pushes certain issues onto the political agenda. As Evans and Tilley (Reference Evans and Tilley2012) observe, however, political parties do not simply respond to social divisions but also manipulate them, highlighting some divisions and playing down others to build winning electoral coalitions. Hence, how prominently a set of issues figures in partisan competition will be mediated by the strategic considerations associated with the coalition-building in which political parties engage (Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2019).

In short, in order to understand whether democratic governments temper the operation of capitalism and in what terms they do so, we need to look not only at formal institutional arrangements or the governing party, but at the terms of political contestation. And those change over time, as the issues of most concern to specific groups rise or fall on the political agenda in response to new events and shifting political cleavages. These are the dynamics I seek to capture with the concept of a representation regime.

The other realm in which processes of representation affect the operation of capitalism is the arena of producer group politics, where organizations representing business and labour contend for influence. In general, there is a rough division of labour between the two arenas. Electoral competition matters more for issues of high salience to large segments of the populace, such as the provision of social benefits, while the details of policy and of industrial relations are worked out in the arena of producer group politics (Culpepper Reference Culpepper2011). However, producer groups, such as trade unions or business associations, often provide critical support for political parties; and this division of labour can change, as issues are mobilized into and out of each arena, with corresponding consequences for whose interests are likely to be addressed (Trumbull Reference Trumbull2005).

As Hacker and Pierson (Reference Hacker and Pierson2010) note, producer group politics is a realm of ‘organized combat’ where the organization of the contending actors matters deeply to whose voices are heard and with what force. Where labour and capital are densely organized and capable of speaking with coordinated voices in systems of neo-corporatist interest intermediation, for instance, they often gain influence over multiple sets of issues (Schmitter and Lehmbruch Reference Schmitter and Lehmbruch1979). Conversely, when the organizational capacities of producer groups decline, they lose influence even over issues normally treated in the realm of producer group politics (Baccaro and Howell Reference Baccaro and Howell2017).

Moreover, the character of producer group organization affects not only the relative influence of capital and labour, but also how the interests of capital and labour become defined (Martin and Swank Reference Martin and Swank2012). Whether trade unions speak primarily for employees in manufacturing or services, for instance, can have a decisive influence on the stance organized labour takes to the transition to a knowledge economy (Rahman and Thelen Reference Rahman and Thelen2019; Thelen Reference Thelen2014). And there is good evidence that the voice and strength of business vary with the types of organizations speaking for it (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010; Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2019).

Hence, variations over time in the organization of producer groups can alter the character of representation regimes. The most obvious example is the recent decline of trade unions, which has undercut the influence of labour over policy. And economic developments that create new divisions of interest between large and small employers or between blue-collar and white-collar trade unions, for instance, have consequences for which interests are pressed most forcefully in the producer group arena (Thelen and Wijnbergen Reference Thelen and van Wijnbergen2003). These issues deserve an extended discussion, but because space here is limited, I concentrate primarily on how changes in the electoral arena affect representation regimes.

The post-war story

If we were to trace the evolution of capitalism and democracy through two centuries of coexistence, we would find many examples of how changes in growth and representation regimes have altered the relationship between capitalism and democracy. The representation regimes of early 19th-century Europe, which conferred influence primarily on wealthy property-holders, for instance, had different implications for capitalism than subsequent regimes of mass suffrage. Here, however, I consider only how the relationship between capitalism and democracy has changed in the developed democracies over the decades since the Second World War with an emphasis on the distribution of well-being. To focus on change over time, I also give short shrift to national variations.

In the terms of this analysis, there have been three eras in the post-war period, each with a distinctive growth and representation regime. I label these: an era of modernization, running from 1945 to 1980; an era of liberalization between 1980 and 2000; and a current era of knowledge-based growth beginning around the turn of the century. Since the pace of change varies cross-nationally, this periodization is only approximate.

I will argue that key distributive outcomes are not the product of changes in capitalism or democracy alone but are co-produced by shifts in both systems. This is not a universal view. Recent increases in income inequality have sometimes been attributed largely to the operation of capitalism (Piketty Reference Piketty2014) or to developments within democracy (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010). Some analysts see a role for both systems but ascribe the actions of governments largely to the dictates of capital (cf. Streeck Reference Streeck2017). By contrast, I argue that distributive outcomes are generated through the interaction of evolving growth and representation regimes.

The era of modernization

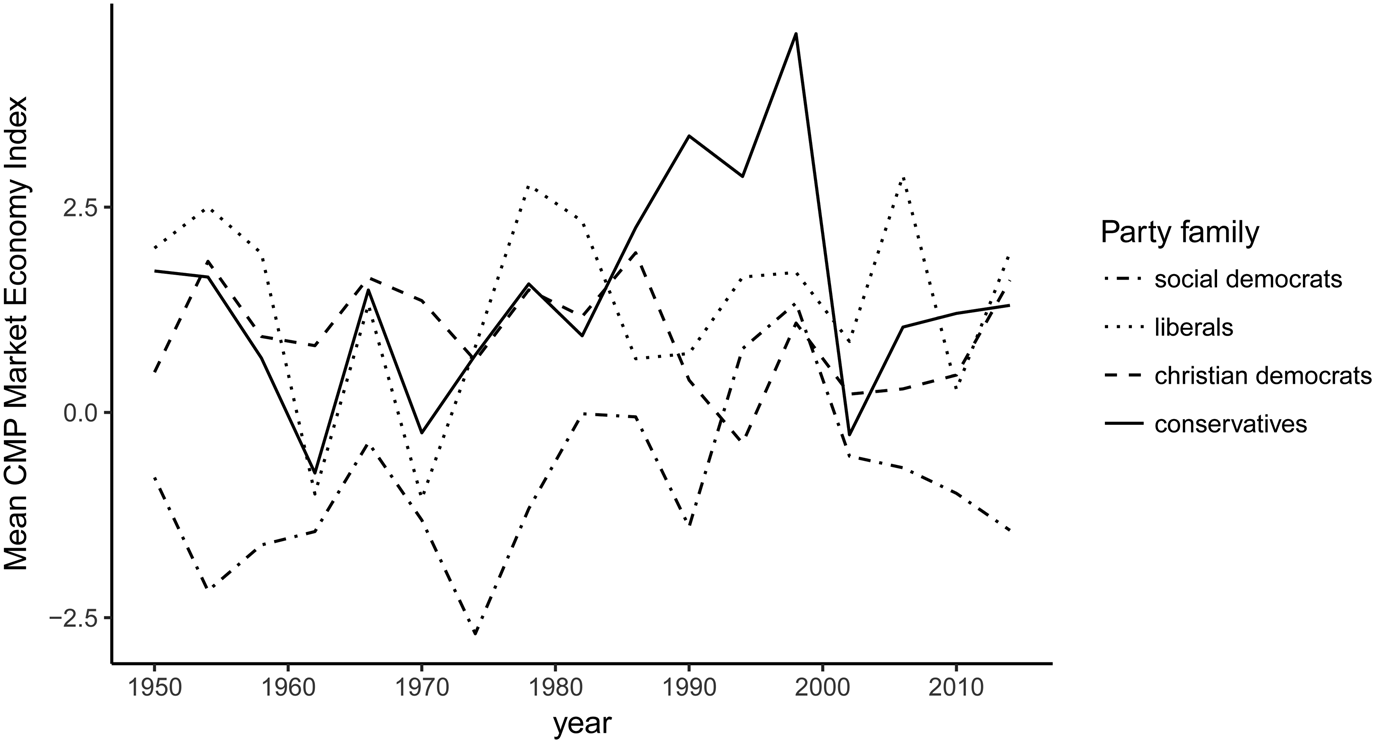

For the developed democracies, the years between 1945 and 1980 were a ‘golden age’ of capitalism marked by high levels of employment (albeit predominantly for men), considerable job security, rising living standards, increasing rates of social mobility and unprecedented declines in income inequality (see Figure 2; Marglin and Schor Reference Marglin and Schor1992). These results flowed partly from high rates of economic growth that owed much to a propitious context in which labour could move off the land into more productive industrial activities (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2007). However, the shape of the growth and representation regimes of this era also made important contributions to its distributive outcomes.

Figure 2. Top Decile Income Shares, 1910–2010

Source: Piketty and Saez Reference Piketty and Saez2013.

At the heart of that growth regime was a distinctive set of firm strategies, three dimensions of which were especially significant. The first was the prominence of Fordist approaches to manufacturing. For most of this era, manufacturing remained important to these economies – accounting for about 40% of employment in the USA and Europe as late as 1960 – and, with some important national variations, manufacturing firms adopted Fordist strategies that deployed semi-skilled labour on long assembly lines to churn out large volumes of standardized commodities (Boyer Reference Boyer1990; cf. Sorge and Streeck Reference Sorge and Streeck2018). Fordist manufacturing provided relatively secure jobs with decent levels of pay to large numbers of workers with modest levels of skill.

The second notable dimension of firm strategy in this period was a widespread quest for scale, on the premise that the competitiveness of a firm depended on its size. Mass manufacturing lent itself to economies of scale and many enterprises became steadily larger in these years, with a corresponding expansion in jobs. Between 1953 and 1972, for instance, the number of firms employing 10,000 workers or more increased from 65 to 160 in Britain, from 26 to 102 in Germany and from 20 to 62 in France (Cassis Reference Cassis1997: 63). Many firms formed diversified conglomerates and adopted the multidivisional form famously described by Chandler (Reference Chandler1993). As a result, white-collar employment also increased steadily in this period (Iversen and Cusack Reference Iversen and Cusack2000) and it became easier for the children of blue-collar parents to move into white-collar jobs, yielding rates of social mobility that lent substance to the concept of ‘meritocracy’ (Erikson and Goldthorpe Reference Erikson and Goldthorpe1992; Young Reference Young1958).

The third key feature of corporate strategies in this era, formalized in proliferating sets of management manuals, was an emphasis on the firm's responsibilities to its employees and community. In 1957, one observer could note that ‘[n]o longer the agent of proprietorship seeking to maximize return on investment, management sees itself as responsible to stockholders, employees, customers, the general public and, perhaps most important, the firm itself as an institution’ (quoted in Davis Reference Davis2009: 10). There were certainly exceptions, but long job tenures, defined-benefit pension plans and internal career ladders helped to make work more remunerative and secure. In these respects, firm strategies contributed to the distributive outcomes of the era (Gomory and Sylla Reference Gomory and Sylla2013).

Many of the public policies adopted in this period were complementary to these firm strategies. Governments regularized industrial bargaining, which helped to secure labour peace and gave organized labour the capacities to push for regular wage increases that underpinned the steady expansion of the demand required for high-volume manufacturing (Boyer Reference Boyer1990; Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen, Crafts and Toniolo1996). Governments discovered the importance of aggregate demand; and various types of demand management, involving counter-cyclical policy or economic planning, offered investors the economic predictability crucial for securing the high levels of capital investment that mass manufacturing required (Hansen Reference Hansen1968). In some countries, social benefits linked to wages gave workers incentives to invest in the skills needed by industry, and more generous unemployment benefits facilitated the rationalization of industry (Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2001; Martin Reference Martin and Crouch1979).

Broadly speaking, the policy stance of Western governments was interventionist and redistributive – designed to foster a ‘mixed economy’ in place of the laissez-faire capitalism of the interwar years. Governments committed themselves to securing full employment and for that purpose embraced activist strategies, ranging from Keynesian demand management in Britain to economic planning in France, initially accompanied by the nationalization of financial institutions and industrial enterprises (Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019; Shonfield Reference Shonfield1969). Perhaps most important, governments laid the groundwork for the post-war welfare state, expanding social protection for the unemployed, sick, disabled and elderly (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001). Although social spending did not rise dramatically until the 1970s, these programmes reflected the social embedding of post-war capitalism.

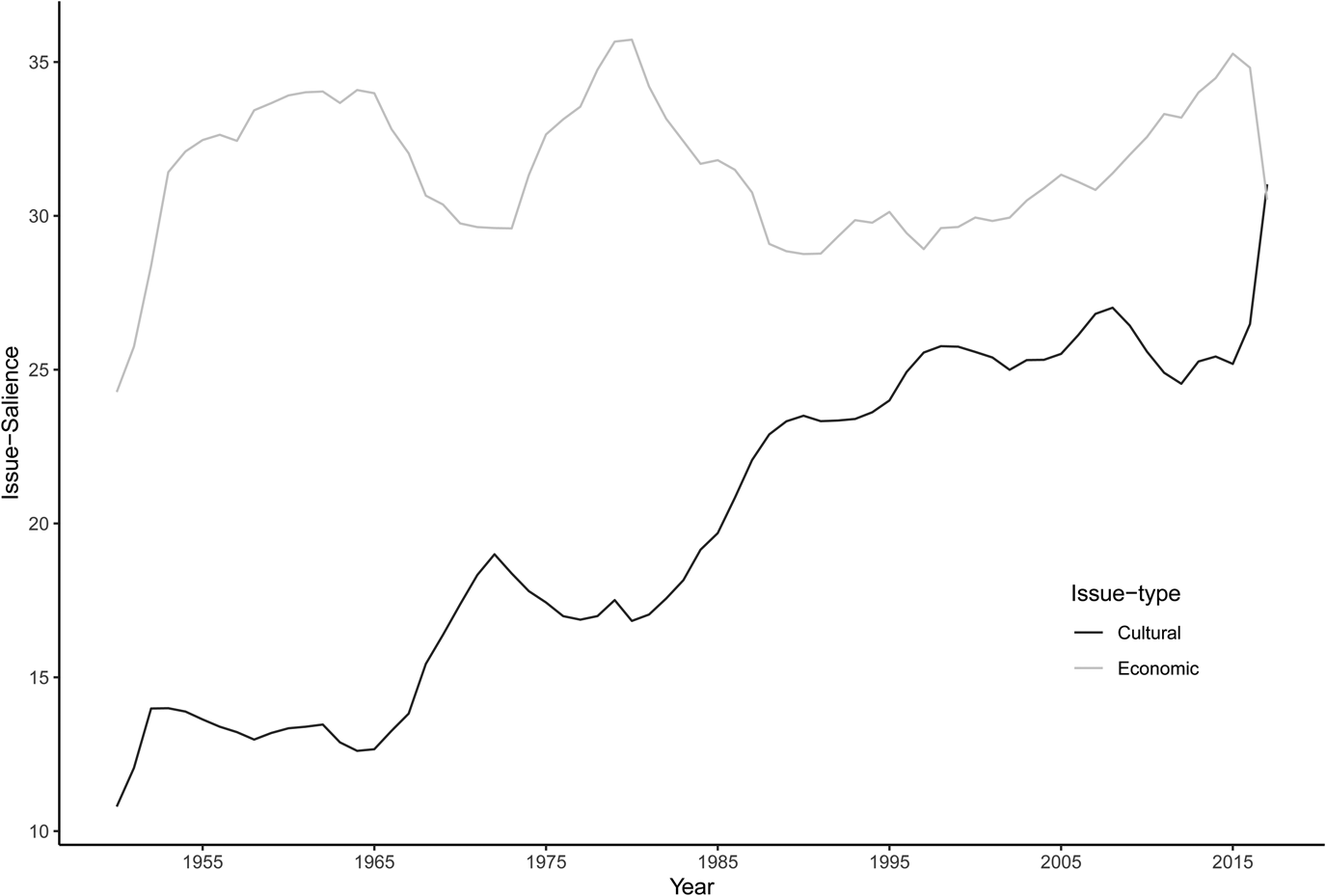

In many cases, capitalists benefited and were far from uniformly opposed to these measures (cf. Korpi Reference Korpi2006; Mares Reference Mares2003; Swenson Reference Swenson2002). For the most part, however, these unprecedented levels of state intervention, new powers for trade unions and a vast expansion of social programmes were the product, not of demands from capital, but of a representation regime that pressed these measures on democratic governments. The key feature of that regime was the centrality of issues of economic rejuvenation and social redistribution to political contestation in both electoral and producer group politics (see Figure 3). In the parliamentary and public discourse of this era, economic issues were presented not as largely technical matters, but as fundamental issues of social justice with deep significance for working people. In most developed democracies, securing full employment became a political imperative, and governments acknowledged social deprivation as one of the fundamental challenges facing them.

Figure 3. The Relative Prominence of Economic and Cultural Issues in the Party Manifestos of Western Democracies

Source: Manifesto Project Database https://manifesto–project.wzb.eu/.

The influence of this agenda is reflected in the fact that governments of both the political left and right engaged in assertive industrial intervention, endorsed the collective bargaining institutions of the post-war economy and expanded the social protections of a growing welfare state. On specific issues, there were certainly divisions of opinion. Conservative governments opposed nationalization and more extensive rights for trade unions, and social democratic governments expanded social policy more aggressively (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001). But the striking feature of policy in this period is that, with some national variations, the mainstream left and right converged on a set of interventionist policies seen as necessary for managing a ‘mixed economy’.

How did issues of economic justice come to dominate this representation regime? Two factors played crucial roles. The first was a popular reaction against the high unemployment and social deprivation of the interwar years associated with the laissez-faire policies of that period. That reaction was reinforced by a burst of social solidarity in the wake of a war in which ordinary people had made inordinate sacrifices, visible in the popularity of socialist and communist parties in the immediate post-war years. ‘Never again’ meant more than no more war: many people wanted economic justice as well as international peace.

The second factor shaping this representation regime was the electoral prominence of a class cleavage, separating a blue-collar working class from a white-collar middle class. In the USA, that cleavage peaked during the 1930s and post-war policy was correspondingly more muted. In Europe, however, this was the pre-eminent cleavage throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Parties on the mainstream left spoke explicitly on behalf of a working class and drew most of their electoral support from it, while the mainstream right drew more votes from the middle class. The prominence of this cleavage meant that political conflict often focused on how to improve the economic situation of working people; and in order to contend for office, even parties of the mainstream right could not ignore such issues. The resulting policies are often described as a ‘class compromise’ in which the political left accepted capitalism, while the political right accepted the economic activism of the mixed economy (Offe Reference Offe1983; Przeworski and Wallerstein Reference Przeworski and Wallerstein1982).

As a result, this was an era in which the popular pressures emanating from democracy had considerable influence over the operation of capitalism. Of course, capital remained influential by virtue of its structural power and role in producer group politics, and many policies were complementary to the corporate strategies of the period. But democratic governments were able to cocoon capitalist firms in webs of regulations, promote the countervailing power of trade unions, and extract funding for growing welfare states, despite considerable opposition from business. Moreover, the distributive outcomes of this era reflected the conjunction of these growth and representation regimes. Large segments of the working class gained decent jobs, security of employment and a share in the fruits of prosperity by virtue of both firm strategies and the policies promoted by a distinctive representation regime.

The era of liberalization

That era of modernization reached its economic apogee and political perigee in the late 1970s, when three decades of rapid growth ended in stagflation. The subsequent decades of the 1980s and 1990s saw profound transformations in both the growth and representation regimes – shifting the relationship between capitalism and democracy and ushering in a different set of distributive outcomes. In those decades, the share of national income going to labour dropped, as wage increases no longer kept pace with productivity; income inequality increased and employment security declined across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, as fixed contracts replaced permanent jobs (see Figure 2). Many people became trapped in low-wage secondary labour markets, and in some countries social mobility declined for each successive age cohort (Chetty et al. Reference Chetty2017; European Commission 2019). This movement in the distribution of well-being followed from important changes in the operation of capitalism, as shifts in firm strategies ushered in a new growth regime. But those strategies were made possible by new sets of public policies linked to changes in the representation regime that undercut the willingness of democratic governments to address the adverse effects of this new capitalism.

Three shifts in the practices of firms were central to the construction of a new growth regime. The first was a reorientation, pressed on firms by increasingly assertive actors in financial markets and rationalized by new managerial ideologies, away from commitments to stakeholders and long-term growth towards the provision of immediate value to shareholders (for an overview, see Davis Reference Davis2009). Firms increased the proportion of their profits distributed to shareholders and became much more attentive to the value of their shares. Dividends as a share of American corporate profits increased from about 42% during the 1960s and 1970s to almost 50% in the 1980s and 1990s; and repurchases of shares designed to reward shareholders soon consumed more than 20% of American profits (Lazonick and O'Sullivan Reference Lazonick and O'Sullivan2000). Although Europe was slower to follow suit, the proportion of profits distributed to shareholders there also increased (Almond et al. Reference Almond, Edwards and Clark2003). To focus top managers on these objectives, their compensation was increasingly tied to the firm's share price. By 2015, three-quarters of the compensation of chief executives in large American firms and about half of their European counterparts' turned on share price, and the ratio of CEO compensation to the average production wage in large American firms grew from about 37 to 1 in 1979 to 277 to 1 in 2007 (Kotnick et al. Reference Kotnick, Sakinç and Guduras2018; Weil Reference Weil D2014).

Second, in keeping with this emphasis on shareholder value, the diversification movement of the 1960s and 1970s was reversed. Companies pared down their holdings to focus on the ‘core competencies’ of the firm. Among leading companies in the world economy, the number that were diversified fell by half between 1980 and 2000 (Franko Reference Franko2004). Of course, this entailed downsizing and serious job losses. Between 1980 and 1993, the 500 largest American manufacturing companies laid off a quarter of their workforce (Audretsch and Thurik Reference Audretsch and Thurik2000; Cappelli et al. Reference Cappelli1997).

Third, facing pressures to downsize, American and European firms began to outsource tasks previously performed by their own employees to subcontractors offering lower wages and fewer benefits. By 1989, more than three-quarters of American employers were subcontracting tasks previously done in-house; and the number of full-time workers in West Germany employed by temporary agencies or subcontractors of cleaning, logistics and security services quadrupled between 1980 and 2008 (Cappelli et al., Reference Cappelli1997; Goldschmidt and Schmieder Reference Goldschmidt and Schmieder2015). The effects were multidimensional and pervasive. Outsourcing forced many workers out of secure jobs offering chances for advancement into low-paid, precarious work on secondary labour markets from which it was difficult to escape (Palier and Thelen Reference Palier and Thelen2010).

A variety of factors pushed firms towards the practices of this new growth regime, including more intense competition from emerging economies, exemplified by the inroads Japanese automakers made into American markets, and freer flows of international capital that fuelled takeover bids after exchange controls were dismantled (Culpepper et al. Reference Culpepper, Hall and Palier2006; Piore and Sabel Reference Piore and Sabel1984; Womack et al. Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990).

However, supportive public policies were again crucial to consolidating the regime. In many countries, the ability of investors to mobilize new financial instruments and pressure firms to deliver shareholder value turned on steps taken by governments to liberalize finance and free up markets for corporate control (Krippner Reference Krippner2011; Lazonick and O'Sullivan Reference Lazonick and O'Sullivan2000). British and American governments made determined efforts to break the power of trade unions to resist downsizing, and government support for decentralizing bargaining had parallel effects in Europe (Baccaro and Howell Reference Baccaro and Howell2017; Riddell Reference Riddell1991). Broad initiatives to eliminate industrial subsidies, privatize national enterprises and deregulate product and labour markets put pressure on firms to rationalize their production, while measures to reduce the level or duration of social benefits and tie their receipt to new work requirements promoted the growth of low-wage secondary labour markets. In general, this was an era in which governments stepped back from intervention to turn the allocation of more resources over to markets and embrace more intense competition as the key to economic growth – steps broadly in keeping with these shifts in firm strategies (Hall Reference Hall and Leibfried2015; Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019).

How is the willingness of democratic governments to embrace this new growth regime to be explained? Some accounts explain these shifts as a response to the functional requisites of capitalism, often citing the prescient 1943 essay by Michal Kalecki, who predicted that post-war capitalism would generate a profit squeeze that governments would have to reverse under pressure from capital (Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019; Streeck Reference Streeck2017). There is clearly something in this: public policies shifted in this era to give more priority to the interests of capital. But how is this shift to be explained? A purely functionalist answer seems insufficient.

Seen in more historical terms, several developments assume importance. The first was the effect of the 1970s climacteric on the attitudes of governments to existing economic policies. High rates of inflation and prolonged economic stagnation which proved impervious to those policies discredited them. As a result, governments began to search for new approaches to inflation and economic growth (Hall Reference Hall1993). That search led them to look with more interest at monetarist doctrines and the rational expectations theories then becoming current in contemporary economics, which emphasized the limits to activist economic management and the value of market competition. Those doctrines were appealing to politicians, not least because they located responsibility for unemployment in the structure of labour markets rather than in governmental mismanagement (Blyth Reference Blyth2002; McNamara Reference McNamara1998).

However, there were also broader overtones to how the crisis of the 1970s was interpreted. As Kalecki (Reference Kalecki1943) noted, the stagflation of the 1970s reflected a breakdown in the industrial relations systems established to regulate distributive conflict between capital and labour. As full employment strengthened trade unions, the incidence of industrial disputes rose. Some saw in this ‘resurgence of class conflict’ a crisis of ‘governability’ that could be addressed only by weakening organized labour, limiting the role of the state and turning the allocation of resources over to competitive markets (Crouch and Pizzorno Reference Crouch and Pizzorno1978; Crozier et al. Reference Crozier, Huntington and Watanuki1975). In many quarters, there was disillusionment, not only with macroeconomic management, but with state intervention itself.

The new policies with which governments experimented were not universally applauded by capital, as Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher found when threatened with a ‘bare-knuckle fight’ by the British Confederation of Industry (Gamble Reference Gamble1988: 191), and firms that faced more competition as a result of deregulatory measures or new trade agreements often opposed them. But business was interested in measures to contain inflation, especially when they imposed new limits on trade union power, and in steps to give markets a greater role in the allocation of resources (Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019). Moreover, as Keynesian doctrines gave way to a ‘new classical’ economics, even social democratic governments were pressed by their economic advisers to implement liberalizing ‘structural reforms’ (Mudge Reference Mudge2018).

Since liberalization was not especially popular, aside from an initial reaction against state intervention in the Anglo-American democracies, many governments took steps to insulate key dimensions of economic policymaking from electoral pressure. In 1986, the member states of the EU endowed the European Commission with powers to liberalize their economies at some distance from electoral scrutiny, and central banks were made more independent of political control during the 1990s. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 established a monetary union that would take monetary policymaking entirely out of the hands of some national governments. In sum, the move to market-oriented policies in the 1980s and 1990s was largely a governmental initiative inspired by a search for more effective policies with which to contain inflation and revive economic growth, fed by new economic ideas and cheered on by many segments of capital.

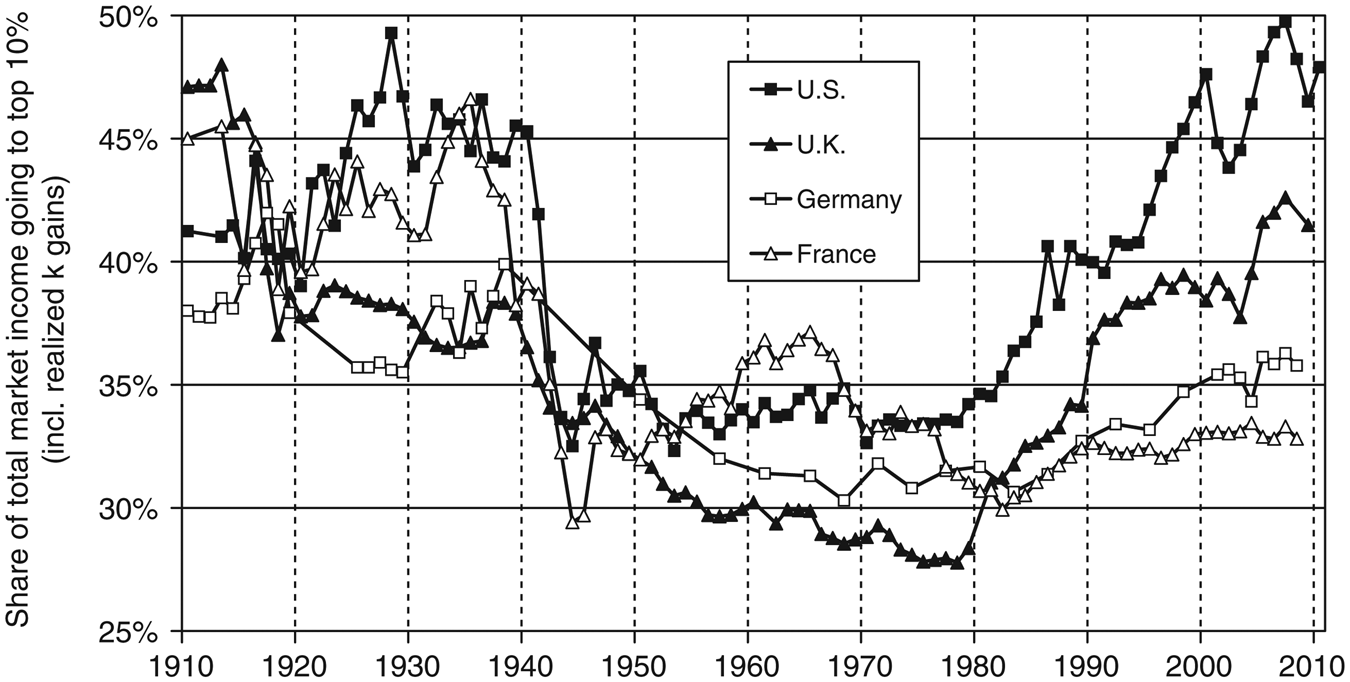

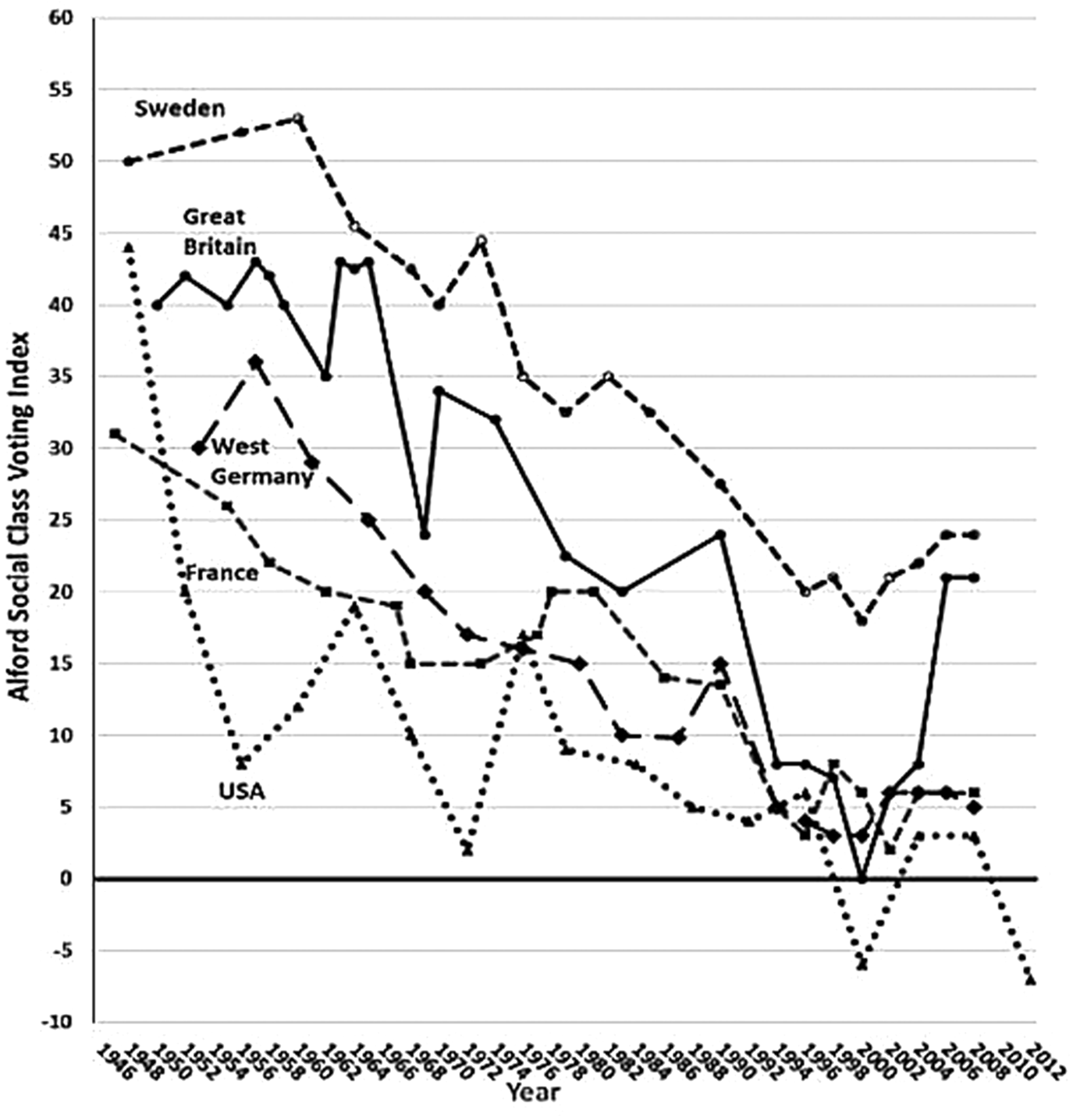

But why did democratic pressure from the many citizens who suffered adverse consequences from these liberalizing moves not pre-empt them? The answer to that question turns on changes in the representation regime linked to shifts in the structure of political cleavages. Several developments were important. The first was a long-term decline in the political salience of the class cleavage which had put previous governments under pressure to protect the working class (see Clark and Lipset Reference Clark and Lipset2001 and Figure 4). By 1980, working people no longer voted so consistently for parties of the left or the middle class for parties of the right. Here we see that political cleavages are to some extent endogenous to growth regimes. The prosperity and new occupational structures promoted by the previous growth regime eroded social divisions between working and middle classes, while its social programmes resolved some of the most serious grievances animating that class cleavage (Manza et al. Reference Manza, Hout and Brooks1995).

Figure 4. Alford Index Indicating the Level of Class-Based Voting, 1945–2012

Source: Inglehart Reference Inglehart2018.

Note: The Alford index reports the proportion of manual workers voting left minus the proportion of non-manual workers voting left.

Even more important was the increasing salience of a second political cleavage based on cultural issues, reflecting new sets of claims for political recognition. This too was endogenous to the previous growth regime. In a quest for modernization, post-war governments had been good at laying concrete. But the experience of growing up under prosperity led new generations to demand something more than peace and the material prosperity that preoccupied their parents (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1990). Beginning in the late 1960s, they took up a series of new post-material causes, including gender equality, environmental protection, racial equality and concern for the developing world. Pursued during the 1980s by new social movements and then by incipient Green parties, these causes became increasingly salient to electoral politics. In many countries, issues of social inequality associated with a new identity politics supplanted issues of economic inequality, shifting the terms of electoral contestation (Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2019).

From the perspective of representation, this was a salutary development. Women, ethnic minorities and environmentalists acquired stronger voices in electoral politics. But the overall effect was to create a second axis of political conflict that cross-cut the long-standing left–right cleavage on economic issues – arraying supporters of post-materialist causes against people holding more traditional and materialist values. The post-materialists were generally younger, more educated and in service-sector jobs, while the traditionalists were often older, less educated and in manual jobs (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi Reference Kriesi1998). Western electorates fragmented, as occupational groups were scattered more widely across what became a two-dimensional electoral space (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. The Location of Occupational Groups in the Electoral Space in 1990/91

Source: World Values Survey (www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp). Countries include: Britain, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the USA.

Note: M = managers; P = professionals; SS = skilled service workers; LS = low-skilled service workers; SE = small employers; SM = skilled manual workers; LM = low-skilled manual workers. Size of circles reflects proportion of each occupational group in the electorate. Axes set at mean values.

To maintain electoral support in this context, political parties had to revise their coalitional strategies, with especially important consequences for social democracy. Facing a need to compete with new Green parties and attract younger voters, centre-left parties took up post-materialist positions (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994). That stance drew increasing numbers of middle-class voters to them on cultural issues. By the 1990s, many European social democratic parties were securing the majority of their votes from the middle class (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015). As a result, it was no longer advantageous for them to operate primarily as parties of working-class defence. Instead, they sought a middle ground and their opposition to market-oriented policies softened, not least because many of their middle-class supporters had strong enough market positions to benefit from them (Mau Reference Mau2015; Mudge Reference Mudge2018).

The result was a shift in the terms of electoral contestation, marked by a self-reinforcing dynamic. As centre-right and centre-left parties converged on economic issues, the political salience of the class cleavage declined even further; and, facing a need to distinguish themselves from their competitors, both sets of parties put more emphasis on their distinctive stances on cultural issues (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2012). Thus, cultural issues became increasingly central to partisan competition and issues of economic equity were relegated to its sidelines (see Figure 3).

For the relationship between capitalism and democracy, the significance of these changes in the representation regime was profound. In the fragmented electoral space of the 1980s and 1990s, the voice of the working class was no longer as loud as it had once been. There were virtually no parties in the south-west quadrant of Figure 5 and the terms of electoral contestation no longer revolved around issues of economic justice (Evans and Hall Reference Evans and Hall2019). Democratic governments continued to exercise considerable influence over the economy: as Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1944) noted, it takes a strong government to liberalize markets (Gamble Reference Gamble1988; Vogel Reference Vogel1996). But the approach of democratic governments to the operation of capitalism shifted, as changes in the terms of electoral contestation altered the responsiveness of governments to the working class.

The new cleavage structure provided a permissive electoral environment in which both centre-left and centre-right governments could respond to the calls of economists and business interests for market-oriented policies. The effect was to shift the balance of influence in the representation regime over economic issues away from the electoral arena towards producer group politics. But business interests were ascendant in that arena – in some cases because they had become more organized (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010) and in others because multiple developments had weakened the voice of labour. The British and American governments had attacked the trade unions, high levels of unemployment forced many European unions into concession bargaining and, as trade expanded, new divisions between unions in the traded and sheltered sectors further undermined organized labour (Pontusson and Swenson Reference Pontusson and Swenson1996; Thelen and van Wijnbergen Reference Thelen and van Wijnbergen2003). As a result, the governments of the 1980s and 1990s proved more receptive to the demands of firms constructing a new growth regime than to calls from labour to limit the adverse effects of that regime.

In short, if democratic forces had exerted considerable influence over the operation of capitalism during the era of modernization, the balance of influence between capitalism and democracy shifted during the era of liberalization in favour of capitalism. In formal terms, democratic governments retained considerable capacities, but in substantive terms what matters is how they use them, and in this era governments became more attentive to the interests of capital and less responsive to a working class suffering the adverse effects of an increasingly inegalitarian growth regime.

The era of knowledge-based growth

Although many of the corporate practices adopted in the 1980s and 1990s remained in place, firm strategies shifted again around the turn of the century in terms significant enough to usher in a new growth regime for the contemporary era of knowledge-based growth. Three changes in corporate strategy marked the movement to this new regime.

The first was the intensive application of new information and communications technology (ICT) to production and sales. Firms had been making some use of ICT for two decades, but only in the early 2000s did the competitive advantage of most large firms become dependent on how effectively they deployed this technology. By 2016, almost 80% of large enterprises in the OECD were using software to manage their resources; almost a quarter of sales for large firms stemmed from e-commerce; and 40% of the development costs of a new automobile were software related (OECD 2013, 2015). Information about the preferences of customers, the performance of employees, how products were used and the operations of suppliers became valuable assets, and capacities to gather and monetize that information became central to the core competencies of many firms. Walmart connects the activities of its 245 million customers directly to its logistics chain at the rate of a million transactions an hour (Durand and Milberg Reference Durand and Milberg2019).

The second key movement in firm strategy was a shift away from investment in physical assets towards investment in intangible assets, such as patenting, trademarking, marketing, research and corporate reorganization (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2016). The leaders here were platform firms, such as Amazon, eBay, Upwork and Google, that matched suppliers with buyers of goods or services. By 2015, platform firms accounted for almost a third of the profits of Western companies (McKinsey 2015). In many cases they do not need extensive physical assets. Although the American hospitality industry depends on $340 billion in physical assets, Airbnb leverages $17 trillion in residential assets without owning any of them. Many of these firms have also substituted contract workers for employees, creating a new precariat around gig work (Azmanova Reference Azmanova2020; Thelen Reference Thelen2019). Amidst this technological revolution, patents have become increasingly important and investments in branding even more vital to sales on the Internet than they were to sales in retail shops. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of industrial designs filed for patent protection tripled, trademark applications doubled and income from intangible investments increased by 75% in real terms (Durand and Milberg Reference Durand and Milberg2019; Haskell and Westlake Reference Haskel and S2018).

The third key feature of firm strategy in this era has been the widespread movement of production into global value chains. This successor to the vertical integration of the 1950s and 1960s organizes production by assigning work on the component parts or services associated with a product to multiple layers of firms located around the world (Berger Reference Berger2005; Milberg and Winkler Reference Milberg and Winkler2013). In many cases, a single product crosses several borders before it is finally assembled. Although some firms have long used foreign suppliers, global value chains are a recent development, facilitated by advances in technology and the new trade arrangements of the 2000s. Between 1995 and 2008, the share of foreign-value-added in global supply chains rose by 75% (Timmer et al. Reference Timmer2014).

However, global value chains affect the distribution of well-being by shifting jobs away from the developed democracies towards emerging economies. If domestic outsourcing was a key feature of firm strategy in the 1980s and 1990s, offshoring became increasingly important in the 2000s (Antràs et al. Reference Antràs, Garicano and Rossi-Hansberg2006; Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Edwards, Crain and Kalleberg2007). Between 1990 and 2008, for instance, the USA added only 600,000 new jobs in tradeable sectors compared with 26 million jobs in non-tradeable sectors; and many large American firms now employ relatively few domestic workers (Spence and Hltashwayo Reference Spence and Hltashwayo2011). The classic example is Apple, which has about 47,000 employees in the USA but relies on more than 700,000 workers in other countries to manufacture its products. By 2007, 12% of American firms were producing goods without any American manufacturing facilities (Bernard and Fort Reference Bernard and Fort2015; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2016).

Once again, public policies were crucial to the emergence and consolidation of this growth regime. The American revolution in information technology relied on decades of public funding for research and development; and relaxed financial regulations during the 1980s arguably increased the willingness of investors to take risks on innovative companies (Block Reference Block2011; Mazuccato Reference Mazzucato2013; Perez Reference Perez, Pyka and Burghof2013). European policies have followed suit on a smaller scale. During the 1990s, the German government made capital available for biotechnology and experimented with a new stock exchange to stimulate innovation; and in 2011 it launched the Industrie 4.0 initiative to promote digital technologies in manufacturing (Casper Reference Casper2007). In the early 2000s, French governments took steps to increase the availability of venture capital, and then shifted regulations to facilitate the formation of new enterprises (Trumbull Reference Trumbull2004). In Sweden, regional development funds were turned into venture capital funds during the 1990s, and trade unions and employers made efforts to stimulate high-tech industry (Ornston Reference Ornston2013; Schnyder Reference Schnyder2012).

At the international level, new trade agreements negotiated between governments were pivotal to the development of global value chains (Palley Reference Palley2018). The admission of China to the World Trade Organization in 2000 was a landmark. With the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) of 1994, the expansion of the European single market to the East in the 2000s, and the termination of quotas under the Multi-Fiber Agreement in 2005, firms gained important new sites for production. New protections for intellectual property rights (IPRs) were incorporated into these agreements to facilitate the expansion of global value chains. After the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), signed in 1995, subjected IPRs to effective international dispute settlement for the first time, hundreds of bilateral investment treaties subsequently stiffened such protections. As Schwartz (Reference Schwartz2019) notes, the priority given to IPRs marked an important new step in American foreign policy.

Finally, changes to social policy also provided support for this new growth regime. The principal move, most prominent in northern Europe, has been a shift in emphasis from policies oriented towards income maintenance towards policies of ‘social investment’ aimed at supplying the human capital crucial to a knowledge economy (Hemerijck Reference Hemerijck2013; Morel et al. Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012). Between 2000 and 2014, European governments increased the proportion of young people in tertiary education from 39% to 62%. Some countries mounted ambitious programmes of continuing education, while others reformed vocational training to confer higher levels of the general skills required by the new economy (Busemeyer and Trampusch Reference Busemeyer and Trampusch2011). On the premise that early childhood development improves human capital, some governments have also increased provisions for day care and parental leave. However, the extent to which social policy has been reoriented towards social investment varies widely across countries (Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi2015).

Amidst this era of knowledge-based growth, the representation regime is changing again – with implications for the balance of influence between capitalism and democracy. Many of the policies sustaining this new growth regime were put in place during the era of liberalization, when the pivotal voter in a fragmented electoral arena often came from middle-class groups that benefited from technological change and the opening of global markets. Some analysts are sanguine that these conditions will continue (Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019).

However, several developments are altering the character of the representation regime in terms significant enough to shift policy in the coming years. The first is a backlash against the rising income inequality and precarity of recent decades, which have fed a fearful discontent that governments can no longer ignore (Engler and Weisstanner Reference Engler, Weisstanner, Carja, Emmenegger and Giger2020). In that respect, high levels of economic inequality are the contemporary analogue to the spectre of interwar unemployment that inspired new policies during the 1950s and 1960s or the economic climacteric of the 1970s that provided an impetus for the policies of the 1980s (Hall Reference Hall, Kahler and Lake2013).

This backlash is now congealing into a new political cleavage – between those empowered by the economic and cultural developments of recent decades and others who feel left behind by them (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi Reference Kriesi1998). Once again, the roots of the new cleavage lie in developments that began under the previous growth regime. As outsourcing pushed workers out of decent jobs into precarious positions in secondary labour markets, many began to feel a resentment that has intensified as offshoring and skill-biased technological change further reduce the demand for routine labour (Autor and Dorn Reference Autor and Dorn2013; Goldin and Katz Reference Goldin and Katz2010). At the same time, the convergence of mainstream parties on economic issues left many feeling unrepresented, while the new prominence of cultural issues in partisan competition increased tensions between people with post-material and traditional values, leaving many feeling that contemporary developments threaten their place in the social hierarchy (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017).

The factor most likely to place people on one side or another of this new cleavage is their level of education. In the knowledge economy, tertiary education has assumed a special political potency because it drives both economic advantage and cultural outlook. In a context of skill-biased technological change, higher education has become the key to a good job; but it also tends to promote post-material values (Weakliem Reference Weakliem2002). People without a tertiary education, who still form about half of the electorate in Western democracies, face increasing economic disadvantages and are more likely to hold traditional cultural outlooks at odds with a cosmopolitan elite discourse (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2020).

The most prominent expression of this cleavage has been growing support for populist politicians on the political right. In Europe, votes for populist right parties increased slowly during the 1980s and 1990s to about 5% of electorates. But in subsequent years their support has risen dramatically to reach close to 20% of the vote in many recent elections. In 2016 it was reflected in both a British vote to leave the EU and an American presidential election (Timbro Reference Timbro2020). In Europe, this new cleavage is visible in declining support for mainstream parties and signs of an incipient political realignment, as voters with a college education move towards Green parties while those with less education move towards parties of the populist right (Häusermann Reference Häusermann2019; Piketty Reference Piketty2018).

This is not simply a return of the class cleavage. There is a class character to the new cleavage: manual workers are especially likely to vote for populist right parties and sociocultural professionals generally vote against them (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). But the strongest support for right populist politicians comes from those a few rungs up the socio-economic ladder – often labour market ‘insiders’ who have reasons to fear that contemporary economic developments will push them further down that ladder (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Häusermann Reference Häusermann2020).

To the extent that the rise of populist politics is undermining tolerance for the views of others and respect for truthfulness in politics, it erodes the quality of democracy, thereby upsetting the balance between capitalism and democracy (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). But, as in the past, the appearance of a new cleavage is also shifting the terms of political contestation – with potential implications for the policy agenda. As mainstream parties come to see rising support for the populist right as the principal threat to their electoral success, they are moving to address the issues animating this cleavage.

To counter the anti-immigrant appeals mounted by populist right politicians, for instance, mainstream parties have begun to adopt stiffer stances towards immigrants, evident in the centre-left in Denmark and the centre-right in France and Austria. But these developments are also beginning to influence the economic platforms of mainstream parties in terms that may presage major shifts in economic policy, and ultimately changes in the growth regime as new policies induce changes in firm strategies. After decades of moving the allocation of resources to markets, many parties on both the centre-left and centre-right are beginning to support more assertive state intervention (Manwaring and Holloway Reference Manwaring and Holloway2021). One manifestation is increasing enthusiasm for Green New Deals – seen as cleavage-bridging programmes that appeal to both middle-class proponents of environmental protection and working people for whom such programmes can create jobs (Bloomfield and Steward Reference Bloomfield and Steward2020; Gustafson et al. Reference Gustafson2019). With increasing support from economists, the American Democrats and British Conservatives are proposing large new programmes to build infrastructure, again with working-class votes in mind. The member states of the European Union have agreed for the first time to issue joint Eurobonds to fund investment, and even in Germany the Greens are arguing for deficit spending.

Economic conditions reinforce the political circumstances conducive to such moves. Amidst low rates of inflation, the equilibrium rate of interest has moved towards the zero-lower-bound, making it possible for governments to raise long-term debt at low cost. That context has inspired new lines of economic argument offering governments a rationale for more expansive spending programmes (Blanchard Reference Blanchard2019; Summers Reference Summers2016). Although some of those moves preceded the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to address that pandemic and revive economies in its wake has inspired interventionist actions that may, in some cases, provide a template for subsequent policy, much as the assertive response to the Second World War did in an earlier era.

At the same time, facing the anti-globalization rhetoric of the populist right, governments are scaling back the unbridled support for global free trade that was a hallmark of the era of liberalization. The most notable moves were made by a populist American administration, but the concerns expressed by some European governments about protecting strategic industries from Chinese predation signal potential shifts there as well. Although cloaked in the rhetoric of free trade, Britain's exit from the single European market is an effort to escape the strictures associated with transnational economic integration. The World Trade Organization languishes; concerns about China's growing economic power increase; and the USA is gradually moving towards the European view that high-technology firms cannot be allowed to operate unimpeded by government regulation or anti-trust concerns.

Of course, many of these steps can be seen as reasonable responses to economic developments, and that may be a necessary precondition for taking them. But governments operate amidst perpetual ambiguity about what is reasonable, and democratic governments respond in the first instance to electorates. Hence, the political momentum behind the new economic activism can be traced to the representation regime. Motivated by changes there, democratic governments are rediscovering the value of state intervention and taking steps to reassert their control over the operation of capitalist markets. Just how far those steps will go remains uncertain, but these are signs that the balance of influence between capitalism and democracy may be shifting once again.

Dynamics

This account is revealing about the dynamics through which capitalism and democracy change. Growth regimes and representation regimes are mutually constitutive of each other. As a result, the process whereby they change is marked by multiple endogeneities rather than stark lines of causality. Firm strategies at the heart of growth regimes respond to opportunities generated by new technology and secular economic developments but also to shifts in public policies that alter the environment for business. Hence, the growth regime of the era of modernization was made possible by the conjunction of secular economic developments and the public policies of that time.

However, growth regimes have economic effects and distributive consequences that often shift the electoral opportunity structures to which governments respond. The prosperity of the immediate post-war decades, for instance, contributed to inflation by strengthening organized labour, but it also eroded the political salience of the class cleavage and inspired the emergence of a new cleavage based on post-material values. As a result, governments were forced to confront stagflation but had the electoral room to deploy market-oriented policies for doing so. Those policies facilitated a shift in firm strategies to which developments in markets for trade and finance were already conducive. In a similar manner, the distributive consequences of the era of liberalization have fuelled a political realignment that is pressuring governments to embark again on more interventionist policies, and the Green New Deals that some governments have adopted are shifting the environment for business in terms that will ultimately work their way into new firm strategies.

It should be apparent that there is no demiurge here. Technological innovation matters, but the pace of its diffusion depends on contemporary policy regimes (Landes Reference Landes2003). Changes in international regimes may make it more or less difficult for democracies to govern capital by shifting the ease with which capital can exit national economies (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2010). But international regimes are ultimately the creation of governments, which directs our attention back to the features of domestic politics that render governments willing to modify them. The overall dynamic visible in these decades is one of symbiosis, in which growth and representation regimes condition each other, in response to evolving sets of economic and political circumstances rather than functional imperatives.

Conclusion

What does this analysis tell us about post-war capitalism and democracy? On the issue of survival, it suggests that, although prosperity has waxed and waned, rumours of the death of capitalism are exaggerated (cf. Streeck Reference Streeck2017). Democracy is more fragile, as Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1944) observed, and under severe strain in some nations. The developed democracies have survived their experiences with successive growth regimes – so far – but authoritarian tendencies among right populist parties carry some dangers for democracy.

Does capitalism dominate democracy? I have argued that post-war experience gives a nuanced answer to that question. On the one hand, capitalists are always influential by virtue of their structural power (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1980), and we see the results in the extent to which public policies have reinforced firm strategies through successive growth regimes. On the other hand, democratic governments are not flotsam and jetsam tossed upon capitalist seas. They are capable of imposing serious constraints on the operation of capitalism, and I have argued that whether they do so depends on the nature of producer group politics and what we might think of as the structure of demand in the electoral arena – phenomena I have tried to capture with the concept of representation regimes.

Thus, the balance of influence between capitalism and democracy turns on the nature of the representation regime. In the realm of producer group politics, which deserves a longer discussion than I have been able to give it here, the quality of representation depends heavily on the organizational power of various segments of labour and capital. In the electoral arena, although partisan alternation in office may matter in the short run, over the long run the most consequential feature of the representation regime lies in the terms in which political contestation is conducted, namely, the issues given most prominence there and how they are framed. When the terms of electoral contestation highlight the concerns of people adversely affected by capitalism, democratic governments are more likely to impose constraints on its operation in the name of social justice. We can think of these as measures that socially embed capitalism (Block and Somers Reference Block and Somers2016).

Accordingly, the balance of influence between capitalism and democracy changes over time in tandem with changes in the representation regime. The representation regime of the 1950s and 1960s led democratic governments to assert the primacy of politics over markets, while the regime of the 1980s and 1990s shifted influence towards a producer group arena where business held the upper hand (Berman Reference Berman2012). However, I see indications that the representation regime of this century may be turning the tables once again.