The extreme right party (ERP) family (also labelled the populist radical right) is considered the fastest-growing party family in the post-war period. This trend is evident in the ERPs’ participation in coalition governments in 11 countries in Western and Eastern Europe and in the granting of parliamentary support to minority governments in four European countries (Golder Reference Golder2016). Moreover, the Front National (FN) was the party with most votes in the French elections for the 2014 European Parliament. This electoral accomplishment was repeated in the first round of the 2015 regional elections (The Guardian 2015). The Austrian 2016 presidential elections were marked by the victory of the far right Freedom Party in the first round (later defeated, in the second round) with 49.7 per cent of the vote (The Guardian 2016). The electoral success of ERPs attracted a disproportionate amount of attention from scholars, focusing on the causes bolstering the upsurge of the parties, which turned this party family into the most studied in political science (Mudde Reference Mudde2016).

By contrast, mainstream party strategies towards ERPs attract far less attention, which helps to explain the limited availability of in-depth research on this topic (Bale et al. Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Yet the electoral inroads that ERPs have made in European party systems pose complex challenges to mainstream parties, both on the left and on the right. Mainstream parties came under increasing pressure to devise strategies to tackle the ERPs’ challenge at the ballot box (Downs Reference Downs2001). In the mid-2000s, a seminal study was published on the relationship between electoral support for niche parties (including ERPs) and the strategies of mainstream parties (Meguid Reference Meguid2008). From then, a limited number of studies were developed on mainstream parties’ strategies towards ERPs, exploring their impact on electoral competition at a cross-national level or the reasons underlying the adoption of particular strategic options (Bale et al. Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Odmalm and Bale Reference Odmalm and Bale2015; Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2017). With very few exceptions (Odmalm and Hepburn Reference Odmalm and Hepburn2017), the causal factors that influence the effectiveness of the strategic options adopted by mainstream parties towards ERP competitors remain unexplored in the literature.

Consequently, this topic remains engulfed in intense controversy, especially in cases where the centre-right parties converged with the policy positions of ERPs (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Some authors associated the rightward shifts of centre-right parties on immigration with the weakening of ERPs’ electoral support (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Meguid Reference Meguid2008). Others argued that accommodation strategies of mainstream parties towards ERPs enhance the latter parties’ legitimacy and their political success (Bale Reference Bale2003; Mondon Reference Mondon2014). In sum, the research question formulated in the mid-2000s of ‘why and how co-optation works in some cases and not in others’ (Schain Reference Schain2006: 272) remains unaddressed. To overcome this shortcoming, this article explores the effectiveness of the strategy adopted by the French centre-right party – the Union pour un mouvement populaire (UMP – Union for a Popular Movement) towards the FN in the French presidential elections of 2007 and 2012 by focusing on the topics of immigration and integration.

Past research into the French political system suggested that mainstream parties uncomfortably adopted the full range of available strategies towards the FN but failed to derail that party’s electoral inroads (Schain Reference Schain2006). Others associated the FN’s electoral entrenchment in the French party system with the successive failures of the French centre right to conduct a successful accommodative strategy due to intra-party divisions, contradictory policy developments and the centre left’s adversarial approach (Meguid Reference Meguid2008). Within this context, this investigation will explore the relationship between the UMP’s and FN’s electoral performances in 2007 and 2012 and the strategic options undertaken by the French centre right. Furthermore, the article will assess a set of hypotheses to understand the effectiveness of the UMP’s strategies towards the FN. To achieve these objectives, this investigation develops a comparative qualitative analysis of the two elections based on a most-similar cases research design. This choice eliminates potential variations in the structural context that could influence the result of the French centre-right strategy towards the FN (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005).

The French presidential elections are contested on the basis of single-member constituencies and according to a ‘two-ballot-majority-plurality’ electoral system wherein the two most voted-for candidates from the first round pass on to the second round (Elgie Reference Elgie2005; Grofman and Lewis-Beck Reference Grofman and Lewis-Beck2005). Based on poll analysis, the case selection enhances the evaluation of the UMP’s strategy towards the FN in the two rounds of the presidential elections. After the in-depth study of the two selected case studies, this investigation provides a comparative synthesis of the identified causal relationships to understand the divergent effectiveness of the centre-right party’s accommodative approaches. Thus, the subsequent investigation is divided into four sections. The first provides an overview of the literature on mainstream parties’ strategies towards ERPs and the hypotheses evaluated in this investigation. The second and third sections explore the patterns of party competition in the 2007 and 2012 presidential elections, and the fourth part provides a comparative synthesis. The final section highlights the contribution of this investigation to the wider literature on political competition between the centre right and ERPs.

Strategic options of mainstream parties towards ERPs

Drawing on the seminal investigation proposed by Bonnie Meguid (Reference Meguid2008), mainstream parties compete with niche parties through their ability to shift policy positions, to manipulate the overall salience in the political agenda and to contest the issue ownership of the emerging party. Following this ‘spatial model of party interaction’, the established parties’ strategies encompass: dismissive strategies, adversarial strategies and accommodative approaches (Meguid Reference Meguid2008; see also Bale et al. Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Downs Reference Downs2001). A dismissive strategy involves the deliberate neglect of the most important issue articulated by the niche party in order to reduce the salience of its political agenda. Therefore, mainstream political elites seek to diminish the niche party’s legitimacy and to enhance its political ostracism (Meguid Reference Meguid2008). Alternatively, an adversarial approach refers to cases in which the mainstream parties adopt the opposite stance on the policy issue introduced by the niche party. Despite the emphasis on the illegitimate character of the niche party’s proposals, this strategic option ends up reinforcing the salience of its political agenda and that party’s issue ownership (Meguid Reference Meguid2008).

Accommodative strategies involve a convergence by the mainstream parties with the policy position articulated by the niche party. This political process has also been labelled engagement, informal co-option or clothes stealing in other studies on ERPs (Downs Reference Downs2001; Hainsworth Reference Hainsworth2008; Schain Reference Schain2006). Through this strategy, mainstream parties acknowledge the importance of the topic dominated by the niche party, increasing its overall salience and adopting a similar policy stance to the one proposed by the new rival. The success of an accommodative approach is supposedly interdependent with a particular timeframe: the early stage of the main issue’s politicization (Meguid Reference Meguid2008). Once an ERP becomes entrenched in the party system, the chances of success for mainstream parties’ efforts to undermine the niche party’s issue ownership decline substantially (Art Reference Art2006). There is a wide expectation that accommodative approaches will most likely help to overturn the new party’s exclusivity on a particular topic, undermine its issue ownership and foster the niche party’s electoral decline (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Meguid Reference Meguid2008).

However, recent cross-national research concluded that ‘broad-based mainstream accommodation’ was not followed by a decline in ERPs’ electoral support. This study recommended the reassessment of the relationship between mainstream party strategies and the radical right’s performance in the polls (Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2017). Furthermore, the deployment of accommodation strategies also involves potential perils as the rightward shift of the centre right can alienate median voters, directly benefiting rival mainstream parties (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995). In this context, this research will identify the strategies employed by the UMP towards the FN for the selected ballots and explore the effectiveness of those strategic choices. This assessment demands the analysis of the issue ownership of opposition to immigration, the rates of electoral support of the UMP and the FN in the first round, and the behaviour of the ERP’s electorate in the second round of the 2007 and 2012 presidential elections.

Drawing on insights based on the literature on mainstream parties and ERPs, this article examines three hypotheses to enhance understanding of the effectiveness of the UMP’s strategy towards the FN in 2007 and 2012. First, mainstream party strategies are supposedly bolstered by the greater legislative experience and governmental efficacy of the mainstream parties. These parties also enjoy extensive access to the media and a wider ability to disseminate their policy preferences across the electorate than niche parties do (Meguid Reference Meguid2008). Hence, the higher degree of party resources and access to the media enjoyed by mainstream parties is supposed to explain the vulnerability of ERPs in the face of the mainstream parties’ strategies.

Hypothesis 1: Centre-right parties’ greater access to electoral resources than ERPs’ fosters the success of the centre-right parties’ accommodative approaches towards ERPs.

Secondly, the lack of effectiveness of mainstream parties’ accommodative or adversarial strategies towards ERPs was associated with endogenous factors related to the observation of intra-party conflicts. Internal divisions can severely affect the credibility of the mainstream party’s selected strategy, delay its implementation or even prevent the adoption of the ideal strategic option (Meguid Reference Meguid2008: 92). The second hypothesis will therefore explore the potential impact of intra-party disputes on the effectiveness of the UMP’s strategy towards the FN in 2007 and 2012.

Hypothesis 2: A lack of internal divisions within centre-right parties boosts the success of their accommodative approaches towards ERPs.

In the context of diminishing party membership and the decline of partisan loyalties across Europe, political competition became increasingly centred on the personality of party candidates (Poguntke and Webb Reference Poguntke and Webb2005). Past research suggested that public preferences at the electoral level became ever more contingent upon the perception of the candidates’ personal traits and their ability to implement the proposed electoral pledges (Carvalho Reference Carvalho2014; Mayer Reference Mayer2007). Therefore, the influence of the UMP’s and the FN’s candidates’ public images on the efficiency of the French centre right’s strategic options at the selected ballots is the third hypothesis examined in this research.

Hypothesis 3: The electorate’s assessment of centre-right candidates’ personal qualities as superior to those of the extreme-right candidates enhances the success of centre-right parties’ accommodative approaches towards ERPs.

The comparison of the relationships between the former hypotheses and the effectiveness of the UMP’s strategies in the two selected cases will enhance the identification of the most relevant causal factor behind the former political process. After this theoretical overview, the next section presents an in-depth analysis of the 2007 presidential elections.

The French 2007 presidential elections

From the mid-2000s to the early 2010s, the French centre right’s electoral strategy was closely associated with the personality of Nicolas Sarkozy (Haegel Reference Haegel2013). Nominated as the UMP presidential candidate in January 2007, Sarkozy’s political campaign had been active ever since his ascension to the UMP’s presidency in 2004. Thereafter, Sarkozy employed this office as a platform for unveiling his electoral strategy for the 2007 presidential elections and adopted a two-pronged approach on immigration and integration (Marthaler Reference Marthaler2008). To secure the UMP’s nomination for the presidential election, Sarkozy sought to distance himself from the unpopular legacy of the UMP president, Jacques Chirac. The French interior minister adopted a confrontational approach towards Chirac, presenting controversial proposals such as the deployment of a quota system to manage inflows and positive discrimination regarding the integration of immigrants (Sarkozy Reference Sarkozy2005). These measures embodied Sarkozy’s overall project to promote a ‘rupture’ with past approaches, but President Chirac vetoed them due to their challenge to French Republicanism (Schain Reference Schain2008). Consequently, this intra-party conflict fostered the interior minister’s image as an outsider vis-à-vis the political establishment, someone who would break with the status quo, and this insulated Sarkozy from the UMP’s negative incumbency effect (Cole et al. Reference Cole, Le Galés and Levy2008).

Parallel to this, Sarkozy’s proposals regarding immigration control sought to neutralize the FN’s threat of dividing the right-wing electorate in the first round of the 2007 election (Carvalho Reference Carvalho2014). At a party convention entitled ‘Selected Immigration, Ensured Integration’, Sarkozy (Reference Sarkozy2005) announced the objective of increasing the share of labour immigration to the detriment of ‘unwanted inflows’ (family reunion and asylum). Notwithstanding Sarkozy’s rejection of ‘zero-immigration policies’, the framing of certain types of inflows as unwanted was distinctive of the FN’s electoral programmes (FN 2001). Thereby, the UMP positions on immigration control shifted onto the FN’s ground in order to mobilize the far right’s electorate in Sarkozy’s favour in 2007, as he himself publicly admitted (Marthaler 2007). Despite the watering-down effects of the presidential veto, the 2006 immigration law introduced substantial restrictions on family reunion as well as a Welcome and Reception Contract to tackle a ‘crisis of the integration system’ (Schain Reference Schain2008). Consequently, Sarkozy’s tenures as interior minister (2002–3, 2005–7) enhanced public perceptions of his statesman credentials and governmental efficiency regarding the promotion of a restrictive approach to immigration (Cautrès and Cole Reference Cautrès and Cole2008).

During the 2007 election campaign, the convergence between the UMP’s stances on immigration and integration and the FN’s discourse was evident, following Sarkozy’s informal co-option of the FN’s cultural xenophobia. According to the UMP candidate, France faced ‘the most serious identity crisis in its history’, which was associated with irregular inflows and the presence of immigrants unwilling to integrate into French society (Sarkozy Reference Sarkozy2007). The framing of immigration as a threat to national identity was a cornerstone of the FN’s ideology under the leadership of Jean Marie Le Pen and in the FN’s electoral campaign in the preceding presidential elections (FN 2001). Thus, the UMP adopted an accommodative approach towards the FN’s stance. The radicalization of the UMP’s positions on immigration and integration was crystallized by a TV interview in which Sarkozy proposed creating a ministry of immigration and national identity (Libération 2007). Furthermore, the UMP manifesto restated the proposal of a quota system to manage inflows and the introduction of further restrictions on family reunion (UMP 2007).

In opposition to the UMP’s rightward shift, the FN watered down its cultural xenophobia, under the influence of Le Pen’s daughter, Marine Le Pen. The FN leader campaigned against globalization, expansion of communitarianism and uncontrolled immigration (FN 2007). Sarkozy’s proposal for a selective immigration policy was opposed, with the defence of zero-immigration policies alongside the deployment of national preference programmes regarding access to the labour market that would favour national citizens (Carvalho Reference Carvalho2014). At the same time, the centre-left candidate of the Parti Socialiste (PS – Socialist Party), Segoléne Royal, failed to deploy an adversarial strategy towards the UMP’s shift onto far-right ground. Whereas Sarkozy proposed the creation of the ministry of national identity, Royal emphasized the importance of the tricolour flag and the national anthem (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2007). This statement reduced the ideological gap between the mainstream parties’ stances on immigration and integration and was considered inappropriate for a centre-left candidate (Bell and Criddle Reference Bell and Criddle2008).

The UMP’s accommodation strategy towards the FN and the emphasis on immigration and integration throughout the electoral campaign resonated with an important segment of the electorate. According to polls, immigration was ranked as the sixth most important issue by 7.1 per cent of respondents (PEF 2007). The FN candidate was still rated as the best candidate for dealing with this issue by 40.9 per cent of the voters, who ranked immigration as their top priority. Nonetheless, Le Pen was closely followed by the UMP candidate, who collected 32.2 per cent of similar responses from those same voters (PEF 2007). Therefore, Sarkozy effectively disputed Le Pen’s issue ownership of opposition to immigration, despite the FN’s long-term entrenchment in the French party system. The French 2007 presidential elections suggest that mainstream parties can effectively contest ERPs’ issue ownership in the later stages of the politicization of immigration.

The UMP’s accommodative approach towards the FN was successful in the first round of the 2007 presidential elections, after Sarkozy collected 31 per cent of the vote with the support of more than 11 million French citizens, whilst Le Pen obtained a mere 10.4 per cent (representing 3,834,530 votes; Bell and Criddle Reference Bell and Criddle2008). Le Pen’s 2007 result represented the FN’s worst electoral performance in a presidential election since 1974 and a substantial decline compared with the electoral peak of 16.9 per cent of the vote obtained in 2002 (Carvalho Reference Carvalho2014). The FN’s electoral contraction benefited the centre-right candidate, with polls indicating that 26 per cent of Le Pen’s 2002 voters transferred their electoral support to Sarkozy (Mayer Reference Mayer2007). In the second round, Sarkozy’s electoral share was strengthened by the overwhelming support of 69 per cent of Le Pen’s voters from the first round, which indicated the acute intensity of the centre right’s seizure of the FN’s electorate (Perrineau Reference Perrineau2008). Consequently, the 2007 presidential elections suggest that ERPs’ immunity to the counter-strategies of centre-right parties is not a permanent political feature and can be severely disturbed in particular circumstances.

The extraordinary effectiveness of the UMP’s strategy towards the FN regarding the issue ownership of opposition to immigration and the electoral behaviour observed at both the first and second rounds of the 2007 presidential elections were positively related to the higher level of party resources enjoyed by the centre-right party in comparison to the selected ERP. According to a media survey, the UMP candidate was the beneficiary of more than 390 minutes of coverage in TV news programmes before the first round, whilst the FN candidate accrued only slightly more than 150 minutes (Gerstlé and Piar Reference Gerstlé and Piar2008: 36).Footnote 1 Secondly, the intra-party disputes over immigration and integration within the UMP were also positively related to the success of Sarkozy’s accommodative approach towards the FN. The disagreements between President Chirac and the former interior minister reinforced the latter’s image as an outsider vis-à-vis the political elite. This detachment was important for the mobilization of voters disgruntled by mainstream politics and those frustrated with past approaches to particular topics such as immigration and integration (Cautrès and Cole Reference Cautrès and Cole2008).

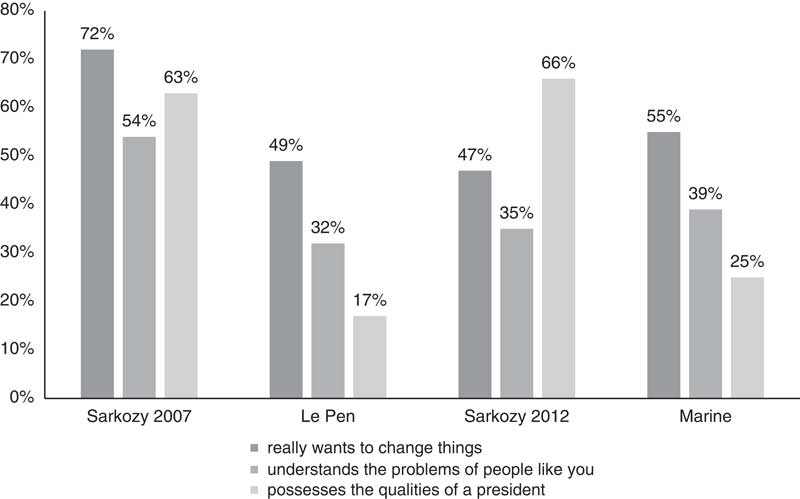

Contrary to expectations, the intra-party disputes on immigration and integration failed to undermine the UMP’s accommodative approach towards the FN as predicted in the literature, having effectively bolstered the efficiency of this strategic option in 2007. Lastly, the success of the UMP’s strategic option was also positively related to the distinct appraisal of Sarkozy’s and Le Pen’s personal traits among the electorate. The UMP candidate was associated with the qualities of a president by almost two thirds of respondents, while Le Pen failed to obtain one fifth of favourable ratings (Figure 1). Similarly, the public polls suggested that the French electorate rated Sarkozy’s ‘willingness to change things’ and his ‘understanding of people like us’ on a much higher level than Le Pen (Figure 1). Consequently, Sarkozy benefited from a positive incumbency effect from his tenures as interior minister that strengthened public perception of his statesman-like qualities. The intra-party divisions on immigration and integration boosted Sarkozy’s project to promote a ‘rupture’ with past policy and his image as an outsider.

By contrast, the FN’s candidate had a deep credibility deficit among public opinion that reflected Le Pen’s pyrrhic victory in the 2002 presidential elections and his political strategy of privileging controversy over policy feasibility (Mayer Reference Mayer2007). Whereas Sarkozy contested his first presidential election and represented a generational shift in domestic politics, the ageing Le Pen (who was 78 years old) had been the FN’s presidential candidate since the mid-1970s and had expended an important share of his political capital (Carvalho Reference Carvalho2014). In short, the success of the UMP’s accommodative strategy towards the FN in 2007 was positively related to the three proposed hypotheses regarding: the higher levels of resources of the UMP, the centre right’s divisions over immigration and integration, and Sarkozy’s higher levels of political capital in the face of a discredited FN candidate. The next section explores the effectiveness of the UMP’s strategy towards the FN in the 2012 presidential elections.

The 2012 presidential elections

The 2012 French presidential elections took place against a backdrop of economic decline, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and President Sarkozy’s deep unpopularity among the electorate. This trend reflected President Sarkozy’s ‘bling’ posture, compounded by personal excesses and public blunders during the first half of his term. The electoral honeymoon was shortened by events such as the post-victory celebration in a luxurious restaurant, short-term extravagant holidays offered by business allies, or the exposing of the president’s private life. These episodes fostered public distrust and the perception of Sarkozy’s unsuitability to perform in accordance with the Gaullist presidential style (Cole et al. Reference Cole, Meunier and Tiberj2013). Simultaneously, two policy U-turns from the cornerstones of the 2007 electoral campaign were observed. Three years after its creation, President Sarkozy abolished the controversial ministry of immigration and national identity and dropped references to national identity in order to prevent further public misunderstandings (Le Figaro 2010). The paradigm of a selective immigration policy was replaced in 2011 by the reduction of regular immigration, due to the failure to increase the share of labour inflows to half of the annual entries (Carvalho Reference Carvalho2016).

Moreover, President Sarkozy’s direct interventions on immigration and integration fostered intense intra-party divisions and political censure at the external level, which hindered the implementation of the policy inputs. After deadly clashes in Saint Agnain in 2010, President Sarkozy ordered the removal of illegal Roma camps and the forced removal of EU citizens of Roma origin living in them. However, intense endogenous and exogenous opposition involving the UMP cabinet and the European Parliament derailed the enactment of this measure. Deep intra-party conflicts resurfaced in 2011 over the Interior Ministry’s decision to deprive foreign students of temporary residence authorizations upon completion of their studies. The opposition within the UMP, led by the education minister, Valérie Pécresse, and former prime minister Jean Pierre Raffarin, forced President Sarkozy to water down the UMP government’s restrictive approach to student immigration (Carvalho Reference Carvalho2016). Unsurprisingly, the 2012 electoral campaign was distinctive for a lack of references to President Sarkozy’s incumbency record or to national identity.

To divert attention from his record in office, Sarkozy announced a series of referendums, including a proposal to facilitate the forced removal of irregular immigrants, despite his past opposition to plebiscites (Lemariè Reference Lemariè2012; Piar Reference Piar2013). The UMP’s position on immigration and integration was clearly located in FN territory after President Sarkozy stated in a TV interview: ‘there are too many foreigners in France’. Therefore, the UMP candidate pledged to halve annual inflows and to reduce foreign citizens’ access to welfare benefits (Vincent Reference Vincent2012). At a political rally with party supporters, Sarkozy framed irregular immigration as a peril to European civilization and threatened to pull France out of the Schengen Agreement if border controls at the European level were not expanded (Sarkozy Reference Sarkozy2012a). These pledges were restated in the UMP 2012 party manifesto, which led a liberal US newspaper to label the centre-right candidate as ‘Nicolas Le Pen’ (UMP 2012; Wall Street Journal 2012).

The UMP thus adopted an anti-immigration stance very close to the FN’s position, which suggested the repetition, if not the escalation, of the accommodative approach employed in 2007 (Hewlett Reference Hewlett2012). Nonetheless, the UMP faced a new and younger far-right challenger, after the ascension of Marine Le Pen to the FN’s leadership in 2011. Following a strategy of de-demonizing the FN, Marine completely dropped references to national identity in favour of Islamophobia and the intensification of the FN’s opposition to the European Union and globalization (FN 2012). Unlike her father, Marine cultivated a serious political style involving consistent proposals to strengthen France and its role in world politics (Fourquet and Gariazzo Reference Fourquet and Gariazzo2013). Parallel to this, the PS candidate, François Hollande, sought to capitalize on the incumbent president’s unpopularity and turned the presidential ballot into an anti-Sarkozy referendum (Cole et al. Reference Cole, Meunier and Tiberj2013). On immigration, Hollande closed ranks with the UMP by adopting a restrictive approach towards irregular immigration, coupled with the acceptance of regular immigration and student inflows (Hollande Reference Hollande2012).

After qualifying in second place for the second round of the presidential election, the UMP candidate’s potential victory over the PS candidate became increasingly dependent on Marine’s supporters (Kuhn and Murray Reference Kuhn and Murray2013). Consequently, Sarkozy intensified the accommodative strategy towards the FN in the electoral campaign between rounds (Chiche and Dupoirier Reference Chiche and Dupoirier2013). According to the incumbent president, the FN under Marine’s leadership conformed to the standards of a ‘democratic party’ whose proposals followed the Republican paradigm, which signalled the first time the FN was accepted as a normal contender by a French president (Mondon Reference Mondon2013). Furthermore, President Sarkozy expressed his support for the establishment of national preference programmes, in a reference to the FN’s welfare xenophobia (Sarkozy Reference Sarkozy2012b). Thereby, the UMP candidate continuously radicalized the centre right’s stances on immigration and integration.

Despite the UMP’s overwhelming emphasis on immigration and integration throughout the electoral campaign, this strategic option failed to resonate with the general electorate (Cole et al. Reference Cole, Meunier and Tiberj2013). In the context of intense public concern with economic issues, the salience of immigration declined, with this topic being ranked as the most important issue by a mere 2.2 per cent of respondents to a post-electoral poll (PPEF 2012). This public poll indicated the FN’s recovery of its hegemony among the diminished segment of voters most concerned with immigration. Marine was ranked as the best candidate to deal with immigration by 67.7 per cent of the voters most concerned with this topic, whilst Sarkozy secured only 19.4 per cent of similar opinions (PPEF 2012). The large gap between the rankings of the two right-wing candidates indicates that President Sarkozy’s rightwards shift failed to challenge the FN’s issue ownership of opposition to immigration in 2012.

The UMP’s accommodative strategy towards the FN also failed at the polls, as President Sarkozy garnered 27.18 per cent of the vote (representing the support of 9,753,629 French citizens) in the first round of the 2012 presidential elections, trailing behind the centre-left candidate. The incumbent president lost the support of 1.7 million voters and only managed to secure half of his 2007 vote share (Chiche and Dupoirier Reference Chiche and Dupoirier2013). By contrast, Marine obtained a strong third place, with 17.9 per cent of the vote, amassing 6,421,426 votes, which represented the FN’s best electoral performance ever in a presidential ballot (Perrineau 2013). According to electoral polls, the UMP strategy in between rounds successfully increased the support for the incumbent president among Marine’s first-round voters (Fourquet and Gariazzo Reference Fourquet and Gariazzo2013). Yet, the UMP’s political convergence with the FN may have also alienated the potential support of centrist voters, as suggested by a public poll conducted before the first round (Piar Reference Piar2013).Footnote 2

Notwithstanding the upward trajectory between rounds, President Sarkozy was unable to repeat the broad success observed in the 2007 elections. In the second ballot, the UMP candidate, having obtained 48.36 per cent of the vote, was defeated by Hollande, who garnered 51.67 per cent of the vote. Post-election surveys indicated that the UMP candidate benefited from the vote transfer of 57 per cent of Marine’s first-round voters but was unable to prevent the centre-left candidate from obtaining the support of 17 per cent of those voters (Perrineau 2013). Effectively, Hollande’s support among over 1 million of Marine’s first-round voters who were disgruntled with the incumbent president was deemed crucial to sustain the centre left’s victory in the second round. President Sarkozy’s ability to capture a substantial share of Marine’s voters in the second round helped reduce the magnitude of his defeat, but was unable to propel him to an overall victory that would have led to a second term (Chiche and Dupoirier Reference Chiche and Dupoirier2013).

The repetition of the UMP’s accommodative approach towards the FN in 2012 failed to tackle the FN’s ownership of opposition to immigration, prevent Marine’s remarkable result in the first round, or halt the defection of 1 million FN first-round voters to the centre-left candidate in the second round. Considering the FN’s rate of success in 2012, President Sarkozy’s management of immigration and integration during his term and the political convergence in the electoral campaign seem to have enhanced Marine’s electoral expansion among the French electorate (Mondon Reference Mondon2014). In the longer term, the convergence between the UMP’s and the FN’s stances on these topics fostered the ideological radicalization of the centre-right electorate. This process helps explain the emergence of two rival camps within the UMP, as was evident in the 2013 internal ballot for the party’s leadership (Haegel Reference Haegel2011, Reference Haegel2013). Another long-term consequence was the erosion of the boundaries between the centre-right and ERP electorates, especially on the topics of immigration and security (Fourquet and Gariazzo Reference Fourquet and Gariazzo2013). This trend fosters the potential observation of electoral swings among the right-wing electorate between the UMP and the FN in the future.

The diminished effectiveness of the UMP’s accommodative approach towards the FN in 2012 diverged from the centre-right party’s more extensive resources compared with the French ERP. Furthermore, Sarkozy benefited from holding the presidency, which provided additional electoral resources, direct agenda-setting powers over the legislative agenda and broad access to the media. Media polls indicate that President Sarkozy obtained more than 223 minutes of TV coverage, as opposed to the 105 minutes accrued by Marine (Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel 2012: 125).Footnote 3 Thus, the vast electoral resources at the UMP’s disposal contrasted with the ineffectiveness of the centre right’s accommodative strategy in 2012. Secondly, the intense intra-party divisions over immigration and integration help explain the successive policy setbacks observed during President Sarkozy’s term (Carvalho Reference Carvalho2016). This trend diminished the UMP candidate’s credibility among the electorate and weakened public perception of his ability to promote a rupture with past approaches. Therefore, the intra-party conflicts over immigration and integration during President Sarkozy’s term undermined the UMP’s strategy towards the FN at the 2012 elections.

Public polls conducted during the 2012 electoral campaign indicate that President Sarkozy’s unpopularity caused direct repercussions on his public image (Chiche and Dupoirier Reference Chiche and Dupoirier2013). By contrast, Marine’s public evaluation excelled in comparison to her father’s rankings in 2007 (Figure 1). The UMP candidate was still perceived by the public as possessing more statesman-like qualities than the FN candidate (Figure 1). However, President Sarkozy’s willingness to change things and his understanding of the problems faced by ordinary people were ranked lower than the FN candidate’s by the respondents to the public poll (Figure 1). Hence, the public perception of the UMP candidate’s ability to promote a rupture with past policy slumped after the presidential term in the face of a young and inexperienced FN candidate. The lower appraisal of President Sarkozy’s personal qualities in the face of a fairly popular FN candidate was thus positively related to the diminished effectiveness of the UMP’s accommodative approach towards the FN in 2012. The next section compares the trends identified at the two selected first-order ballots.

Comparative synthesis

This investigation suggests that the French centre-right party adopted accommodative approaches towards the FN in both the 2007 and the 2012 presidential elections. While this strategic option was embodied by Sarkozy’s informal co-option of Le Pen’s cultural xenophobia in 2007, the deployment of a similar strategy in 2012 involved the UMP’s convergence towards the anti-immigration stances proposed by the FN under Marine’s leadership. An important level of variation was identified in the contents of the UMP’s accommodative approaches, which suggest that the configuration of this strategic option evolves over time rather than being static. The FN’s issue ownership of opposition to immigration was effectively contested by the UMP candidate in 2007, whilst the French ERP’s hegemony regarding this topic was fully recovered by 2012. Therefore, ERPs’ hegemony over opposition to immigration is not inevitable and can be disrupted by mainstream parties despite the former’s long-term entrenchment in the party system. However, public polls suggest that the French centre right’s accommodative approach towards the FN on immigration and integration resonated with a salient segment of the electorate in 2007, whereas it only appealed to an electoral fringe in 2012.

Similarly, the UMP’s accommodative approach towards the FN entailed the capture of a substantial share of Le Pen’s 2002 electorate in the first round of the 2007 presidential elections. Nonetheless, the insistence on this strategic option in 2012 was followed by the FN’s best performance ever in a presidential ballot. Like the trend observed regarding the issue ownership of opposition to immigration, the effectiveness of the UMP’s accommodative strategy was much weaker in the first round of the 2012 ballot than in 2007. Regarding the electoral behaviour in the second rounds, the UMP’s candidate collected the support of 69 per cent of Le Pen’s first-round voters in 2007 but only 57 per cent of Marine’s supporters in 2012. The vote swings among right-wing voters in 2012 were significant but insufficient for President Sarkozy to obtain a second term, especially after the UMP’s strategy failed to prevent an important share of the FN’s first-round electorate from transferring their support to the centre-left candidate. These trends suggest that the UMP’s accommodative approaches towards the FN were successful in 2007 but much less effective in 2012. Thus, the electoral effects of centre-right parties’ accommodative approaches towards ERPs should be interpreted as a contingent outcome rather than an unavoidable success.

The comparative analysis of the relationship between the proposed explanatory factors and the effectiveness of the UMP’s accommodative approaches highlights the importance of the public perception of right-wing candidates’ personal qualities. By contrast, the UMP’s higher level of party resources, compared with that of the FN, held a weak relationship with the effectiveness of the French centre right’s accommodative approaches. Whereas a positive relationship was observed in 2007, the diminished effectiveness of the UMP’s strategy towards the FN in 2012 diverged from the party’s increased advantage in terms of electoral resources in that election. Secondly, the intra-party conflicts within the UMP over immigration and integration contained distinct effects over the effectiveness of the centre right’s accommodative approaches towards the FN. The intra-party disputes observed during President Chirac’s term enhanced the UMP’s accommodative strategy in 2007 because they boosted Sarkozy’s image as an outsider vis-à-vis the political establishment. Similar disputes over President Sarkozy’s agenda on immigration control and integration diminished his credibility and the public perception of the president’s legislative efficiency, which undermined the UMP’s accommodative approach in 2012.

Therefore, this investigation highlights that intra-party conflicts within centre-right parties can create mixed effects with regard to accommodative approaches towards ERPs, as they can either enhance or undermine the effectiveness of this strategic option. Thirdly, the large differential in the public ranking of the personal qualities of the UMP’s and the FN’s candidates was positively related to the effectiveness of the UMP’s accommodative approach in 2007. In contrast, the decline of President Sarkozy’s popularity compared with Marine’s progress in public opinion was positively related to the diminished effectiveness of the UMP’s convergence with the FN on immigration and integration in 2012. Therefore, the overall success of the UMP’s accommodative approaches seemed more related to public appraisal of the centre-right and far-right candidates’ personal qualities than to the levels of party resources or the observation of intra-party conflicts. These trends suggest that Sarkozy’s accommodative approach in 2007 benefited from exceptional circumstances due to the FN candidate’s deep credibility crisis. The redeployment of this strategic option in 2012 backfired in the face of a ERP challenger endowed with stronger credibility among the electorate.

Conclusions

This investigation associated the UMP’s accommodative approach with the FN’s electoral decline in 2007, whereas the adoption of a similar strategic option in 2012 was accompanied by the FN’s best ever performance in a presidential ballot. The research also suggested that ERPs’ immunity to a centre-right party’s challenge is not perpetual and that an ERP’s electoral support can be seriously weakened, in certain circumstances. ERPs’ issue ownership of opposition to immigration can also be challenged by centre-right parties, even after the ERPs have become entrenched in the domestic political system. Nonetheless, the 2012 presidential elections showed that a centre-right party’s adoption of accommodative approaches is not necessarily followed by the weakening of the ERP’s electoral support, nor does it guarantee the overwhelming support of ERP voters for the centre-right party’s candidate in order to secure a victory in the second round of a presidential ballot. Therefore, this research warns against the potential pitfalls of inducing the electoral outcomes from the mainstream parties’ strategic options towards ERPs without conducting in-depth analyses of this political process. This article suggests that the short-term electoral effects of mainstream parties’ accommodative approaches towards ERPs are a contingent political process with uncertain consequences.

The divergent effectiveness of the UMP’s accommodative approaches towards the FN in 2007 and 2012 was weakly related to the unequal electoral resources enjoyed by the right-wing party. Whilst intra-party conflicts had ambivalent effects on the success of this strategic option. Thereby, the effects of internal disputes over immigration and integration on centre-right parties’ strategies towards ERPs also have a contingent character whose evaluation demands in-depth research. By contrast, the distinct effectiveness of the UMP’s accommodative approaches was positively related to the discrepancy in terms of public perception of the personal qualities of these parties’ candidates. Notwithstanding the convergence between the UMP’s and the FN’s political programmes in 2007 and 2012, this research suggests that ERP voters tend to opt for the ‘original rather than the copy’ when faced with a choice between a credible ERP candidate and an unpopular centre-right candidate. Thus, centre-right parties’ accommodative approaches can eventually legitimize ERPs’ electoral agenda. In the long term, the continuous radicalization of the centre-right party’s positions on immigration and integration can have important repercussions at an internal level and may increase the erosion of partisan loyalties among right-wing parties.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia under Grant PTDC 1069/2014. The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, whose comments helped improve and clarify this article.