Democratic backsliding is a much-studied development in contemporary global politics, with political and institutional challenges to liberal democracy and the rule of law becoming widespread. Central Europe, in spite of the European Union's de jure requirement that its members be liberal democracies, is no exception. Among EU members, democratic backsliding has proceeded furthest in Hungary and Poland. In Hungary, Fidesz, a right-wing party, has consolidated control since 2010, undermining the exercise of free democracy while maintaining a constitutional supermajority. In Poland, the Law and Justice party (PiS) has attacked the judiciary and rule of law while implementing a conservative, nationalist project. Backsliding began earlier and has advanced further in Hungary, but the strategies and intentions of both parties in consolidating dominance are strikingly similar; as PiS's leader Jarosław Kaczyński stated in 2011, ‘Viktor Orbán gave us an example of how we can win. The day will come when we will succeed, and we will have Budapest in Warsaw’ (quoted in Kelemen Reference Kelemen2017: 227). The EU has opened formal sanctioning procedures against both backsliding members, though in neither country have the trends reversed.

Most discussion of democratic backsliding focuses on mechanisms by which dominant parties cement their political control at the national level. Studies of how dominant-party regimes are constructed and consolidated typically overlook local politics because political parties, even dominant ones, tend to be less organized at the local level, and extending national party organizational influence over territory is costly. At the same time, however, the ideological appeal of right-wing populist parties tends to be strongest outside the major cities – that is, in the small- to mid-sized towns that constitute the bulk of municipal government. Thus, it is an open question which of these forces will prove decisive in shaping nationally dominant parties’ capacity to capture local-level offices. Because of this uncertainty, local politics has important implications for the dominant party's national-level hold. If the opposition can retain a foothold through winning local elections, it can use that foothold to challenge dominant parties in higher-level arenas later. Likewise, a dominant party that wins local elections not only closes off this avenue for challenge; it can also use perks to extend its appeal to the electorate and change rules to solidify control.

These considerations prompt our central research question: can municipal elections serve as a backstop against the consolidation of the dominant party's control in de-democratizing regimes and, if so, how? We consider two possibilities for this control: electoral institutions and candidate strategy, both of which may help opposition candidates overcome difficulties in coordination. These coordination difficulties are particularly relevant for post-communist local politics because parties tend to be under-institutionalized, candidates less professionalized, political resources few, and independent candidates common. In terms of electoral institutions, one variation in particular would seem to be critical: the distinction between one-round and two-round, or runoff, systems. Two-round systems greatly reduce the need for opposition candidates to coordinate with each other because the first round has the potential to focus the race on the most viable opposition candidate. In the absence of favourable electoral institutions, overcoming dominant-party candidates requires strategic cooperation among opposition candidates to unite around the most viable challenger to the dominant party among them.

In our empirical analysis, we compare two prominent examples of backsliding, Hungary and Poland, to examine dominant parties’ success in penetrating local politics by focusing on mayoral elections. Both Fidesz and PiS are right-wing parties, so both tend to be structurally disadvantaged in larger urban areas. They differ in one key respect, however: in Hungary, Fidesz has been able to duplicate its national-level success in subnational elections, winning a majority of the mayoral elections it contests. PiS has not been able to replicate this success and has not consolidated its control subnationally, where the opposition has had several well-publicized victories setting up its candidates as potential challengers to the dominant-party regime. Hungary and Poland also differ in that Hungary uses a single-round mayoral electoral system, while Poland uses a two-round system.

In pursuing a structured, focused comparison of cases that are broadly similar in terms of overall context but differ in terms of a key theoretical variable (i.e. electoral system), we are employing a ‘most similar systems’ research design (Przeworski and Teune Reference Przeworski and Teune1970). This offers the attention to causal mechanisms characteristic of case-study designs while mitigating the loss of comparative leverage also characteristic of such designs. Further, by using a large-N sample of municipalities within our country cases, we can statistically analyse our theoretical propositions. This method has been fruitfully applied to studying the effects of electoral rule differences on election results within the region (Stegmaier and Marcinkiewicz Reference Stegmaier and Marcinkiewicz2019). We use pre- and post-regime establishment panel data on mayoral election results in Poland and Hungary to better understand the variation in subnational consolidation of right-wing regimes and why PiS has been unable to replicate the urban electoral success that Fidesz has achieved. Hungarian mayoral data, covering 2006–14, come from Matthew Stenberg (Reference Stenberg2018), while the Polish mayoral results panel, covering 2014–18, represents original data collection. Each panel is built from local electoral data aggregated by its respective national electoral agency (see Table 3). Overall, we find evidence that two-round electoral systems advantage opposition candidates but little evidence that strategic coordination on its own is effective in blocking the encroachment of dominant parties into local government.

We proceed in three parts. First, we examine democratic backsliding, subnational politics and electoral institutions in Poland and Hungary, arguing that local politics is an important, if less recognized, site for dominant-party regime consolidation. Second, we introduce our data and hypotheses about electoral institutions and candidate strategy. Finally, we discuss our results and their implications for democratic backsliding.

Democratic backsliding from a local perspective

Democratic backsliding describes a process by which ruling parties undermine political and civil societal institutions to tilt the playing field in their favour, effecting a form of gradual regime change which may travel through various stages (semi-consolidated/electoral democracy, hybrid regime/electoral- or competitive authoritarianism), potentially culminating in stable authoritarianism. Analysts describe a common playbook used by dominant parties: undermining the fairness of elections; discretionary use of legal instruments to undermine civil liberties; and restricting the opposition's access to public resources, the media and the judicial system (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010: 7–12). There is consensus among analysts that Fidesz and PiS have both borrowed heavily from this playbook, but also that Fidesz has been more successful thus far in doing so.

The origins of Hungary's backsliding date to Fidesz's winning a constitutional supermajority in 2010. This supermajority allowed Fidesz to enact institutional and policy changes designed to lock in long-term dominance: changes to the constitution, Cardinal Laws and rule of law (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018); constitutional court-packing (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2017); restrictions on media (Bajomi-Lázár Reference Bajomi-Lázár2017) and academic freedom (Enyedi Reference Enyedi2018); and attacks on civil society (Kover Reference Kover2015). Poland's PiS won an absolute majority in 2015, aided by the United Left coalition's inability to reach the 8% minimum threshold. Lacking Fidesz's supermajority, PiS has not been able to change the constitution directly. Instead, PiS has sought to undermine the rule of law to the extent it can work outside the limits of constitutionalism (Sadurski Reference Sadurski2018). It undermined the Constitutional Tribunal by packing the court and reducing its scope, before instituting measures to reduce the independence of lower-court judges (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018: 196). Further echoing Hungary, the PiS-led government has limited freedom of assembly (Sadurski Reference Sadurski2019) and restricted media freedom (Stanley and Cześnik Reference Stanley, Cześnik and Stockemer2019), especially of state-funded broadcasts and publications.

Figure 1 plots the V-Dem Institute's national-level measure of liberal democracy for both countries, highlighting Hungary's earlier backsliding but also Poland's subsequent convergence. Between 2009 and 2019, Hungary and Poland's liberal-democracy scores declined by 0.36 and 0.33, respectively. This decline pushed Hungary's regime into the ‘electoral-authoritarianism’ category in 2019 (Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Lührmann and Hellmeier2020: 915); Freedom House downgraded Hungary from ‘semi-consolidated democracy’ to ‘transitional or hybrid regime’ in 2020 (Freedom House 2020). András Bozóki and Dániel Hegedűs categorized Hungary as a hybrid regime as early as 2014 (Reference Bozóki and Hegedűs2018: 1174). Poland is still classified as an ‘electoral democracy’ by V-Dem and as a ‘semi-consolidated democracy’ by Freedom House. In Bozóki and Hegedűs's words, ‘the dismantling of democracy and rule of law in Poland is still in progress, while in Hungary the hybrid regime is already entrenched and stabilized’ (Reference Bozóki and Hegedűs2018: 1177).

Figure 1. National-Level Democratic Backsliding in Hungary and Poland (1989–2020)

Source: Varieties of Democracy v11.1, www.v-dem.net/en/data/data/v-dem-dataset-v111/.

We believe that there are enough similarities between municipal elections in Hungary and Poland to make comparing them instructive, even acknowledging differences in the degree of national-level backsliding.Footnote 1 Certainly, the national-level regime matters to opposition candidates’ strategies in municipal elections. In a stable democracy, local parties offer programmes tailored to their voters and urge those voters to vote for their candidate; however, in authoritarian conditions or when democracy is under threat, opposition parties may urge supporters to vote tactically – that is, to back the most viable opposition candidate in order to defeat the dominant party, programmatic differences notwithstanding. Since, typically, parties ‘are conservative organizations and resist change’ (Harmel and Janda Reference Harmel and Janda1994: 278), it takes extraordinary circumstances – such as democracy itself being at risk – to induce this kind of change in party behaviour, a point that we will develop in presenting our hypotheses. The degree of backsliding is significant enough in both countries to cast local politics in the light of challenging de-democratization.

If national regime matters to subnational politics, there are also theoretical and historical reasons to believe that subnational politics matter to national regimes. As Ulrik Kjær has observed, local representation can be both a ‘“respirator” that brings a party through difficult times and makes it possible for it to gain strength and re-enter the national parliament’ and an ‘incubator’ of new parties struggling to find their footing in national politics (Kjær Reference Kjær, Blom-Hansen, Green-Pedersen and Skaaning2012: 202). This kind of impact may be even greater in de-democratizing regimes. Studying it can enrich the broader literature on how subnational levels of government can be areas of institutional divergence challenging the logic of the national political regime (Gibson Reference Gibson2012; Key Reference Key1984). This literature is often framed through the lens of subnational authoritarianism, where residual pockets of undemocratic rule persist in otherwise democratic regimes. However, in backsliding regimes the opposite can sometimes be true, and urban centres can form a more liberal, more democratic centre of opposition resistance (Diaz-Cayeros and Magaloni Reference Diaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2001; Wallace Reference Wallace2013). This is one way to view the position of cities in contemporary Poland and Hungary. It is not only that the ruling parties are less successful electorally in cities. Cities can challenge ruling parties through their economic power and ability to contradict national government policies. A recent example was the Warsaw City Council's decision to expand protections for LGBT residents, strongly contradicting PiS's programme (O'Dwyer Reference O'Dwyer2019). Making a further stand against illiberal developments in the region, Budapest and Warsaw, together with Prague and Bratislava, formed the Pact of Free Cities, collaborating to increase their leverage against national governments and seek external support (Hopkins and Shotter Reference Hopkins and Shotter2019).

There are also historical reasons for focusing on local government when analysing democratic backsliding in Central Europe. Devolving power from central to local governments was seen as key to breaking the power of the old political elites and communism's hyper-centralization (Regulski Reference Regulski, Sochacka and Kraśko1996). Because of the perceived centrality of local government in the transition from communism in the 1990s, there is significant policymaking and resource allocation at the local level. Poland's local governments have maintained among the highest levels of autonomy in Europe, particularly in terms of policy scope, organizational autonomy and voice in higher-level policymaking (Ladner et al. Reference Ladner, Keuffer and Baldersheim2019: 232). Though on par with Polish localities in the 1990s, the autonomy of Hungarian localities has declined substantially (Ladner et al., Reference Ladner, Keuffer and Baldersheim2019: 142, 338). Andreas Ladner et al. (Reference Ladner, Keuffer and Baldersheim2019: 341–345) describe local governments in Hungary as ‘bureaucratized’ and ‘subordinate’ to the centre, whereas Poland's are ‘empowered’ and engage in ‘thick coordination’ with the centre. At least some of the decreased autonomy of Hungarian municipalities is strategic. In 2010–11 Fidesz amended local election rules and Hungary's Fundamental Law governing local government (Mötv) to advantage itself structurally at the opposition's expense and recentralized many aspects of policymaking to allow itself more direct control should the opposition be successful in municipal elections (Soós and Dobos Reference Soós and Dobos2014). Though the power of directly elected mayoralties inclines both Fidesz and PiS to pursue them actively, municipalities’ weaker autonomy in Hungary may help explain Fidesz's greater success in these races. It may also be argued, however, that the greater autonomy of Polish municipalities increases their value to both the ruling party and its challengers.

Mayoral election success: similar conditions, different outcomes

Mayors in both Poland and Hungary are directly elected. In Hungary, all elections are single round, and only a simple majority is required to win a municipal mayoral election. In Poland, if no mayoral candidate obtains an absolute majority in the first round, a second-round election is held two weeks later between the top two first-round candidates. This is a key institutional difference between the two countries.

Hungary's Fidesz has been remarkably successful at the local level, steadily increasing its reach into municipal politics. In 2014, Fidesz won 70% of mayoral elections that it contested in Hungarian towns and cities, after winning only 32% in 2002 (Stenberg Reference Stenberg2018). This is no accident. Fidesz consciously manipulated city council rules and regulations to reduce oversight and fair contestation in municipal politics (Jakli and Stenberg Reference Jakli and Stenberg2021). It then used local resources clientelistically to ensure the support of voters (Mares and Young Reference Mares and Young2019). Ultimately this has helped Fidesz to overcome the traditional success of the Hungarian left in urban areas.

Local electoral politics in Poland have generally followed a different pattern. Parties have never played a predominant role in municipal electoral politics (Gendźwiłł Reference Gendźwiłł2012). While the share of candidates and elected councillors going to party-affiliated candidates had been increasing before 2010, this peaked in that year and then markedly declined following local election reforms (Gendźwiłł and Żółtak Reference Gendźwiłł and Żółtak2017: 123). Poland shifted from using party lists to single-member districts in most city council elections in 2012, although lists were retained in larger cities. While independent lists were already dominant in local elections, the reform further strengthened those lists affiliated with elected mayors (Gendźwiłł and Żółtak Reference Gendźwiłł and Żółtak2017). Party politics have not penetrated municipal elections significantly, though parties are increasingly interested in contesting local elections (Gendźwiłł and Żółtak Reference Gendźwiłł and Żółtak2014).

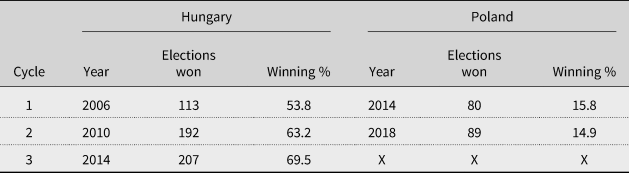

Table 1 shows the respective electoral success of Fidesz and PiS in mayoral elections immediately before and after taking control nationally. The denominator in the winning percentage column is the number of races that the party actively contests as opposed to the total number of possible races.

Table 1. Ruling-Party Wins in Mayoral Elections by Electoral Cycle

Source: Authors’ calculations.

As additional context on national-party penetration into subnational politics, Figure 2 presents data from V-Dem on the extent to which a ‘single party control[s] important policymaking bodies across subnational units (regional and local governments)’. The clear historical baseline in both countries is a lack of influence of any one party subnationally. In Poland, this lack of influence remains the general trend after the rise of PiS, even allowing for an uptick following the 2018 subnational elections. Meanwhile in Hungary, Fidesz's rise has coincided with a significant shift towards national party penetration of subnational governments.

Figure 2. National Party Influence at the Subnational Level in Hungary and Poland Compared (1989–2020)

Source: Varieties of Democracy v11.1, www.v-dem.net/en/data/data/v-dem-dataset-v111/.

Note: The scale of subnational party control is reversed and follows the scale:

0: In almost all subnational units (at least 90%), a single party controls all or virtually all policymaking bodies.

1: In most subnational units (66–90%), a single party controls all or virtually all policymaking bodies.

2: In few subnational units (less than 66%), a single party controls all or virtually all policymaking bodies.

Although parties have nationalized local politics more in Hungary than in Poland, the urban–rural cleavage remains especially salient in both. In national elections, conservative parties tend to do better in rural areas and smaller towns and cities, while the centre-right and left-wing opposition are more successful in urban areas. Kamil Marcinkiewicz (Reference Marcinkiewicz2018) finds significant and substantively large county-level effects on political support for Polish parties in his analysis of 2015 national election results: PiS and the Polish People's Party (PSL), a conservative agricultural party, are much less likely to be supported by urban areas, whereas greater urbanization leads to much higher support for more liberal or left-wing parties. Moreover, he finds that the urban–rural divide explains divergent political support better than any other explanation.

This comparison suggests that municipal elections may potentially impede the consolidation of dominant-party regimes. Although PiS has duplicated many of Fidesz's national-level successes – limiting democratic contestation, reducing media freedom, undermining the opposition, weakening the rule of law and mobilizing rural support in national elections – local-level races have proved beyond its reach. We now investigate why, focusing on electoral rules and candidate strategy.

Hypotheses

If the subnational divergence between Hungary and Poland described above indicates that municipal elections could impede the consolidation of dominant-party regimes in the context of democratic backsliding, the question becomes how? Two possibilities are favourable electoral rules and strategic coordination among opposition candidates. Insofar as candidate strategies are adaptations to electoral rules, the latter are theoretically a given; however, to highlight the difficulties of opposition coordination in dominant-party regimes, we begin with strategies.

A central contention of the party competition literature is that combating a ruling party requires uniting the opposition around a strong candidate: this minimizes the risks associated with splitting the anti-regime vote among opposition candidates, allowing them to form a bloc. Such coalition formation is often labelled a unified opposition strategy. It has received widespread media attention in a variety of contexts. It was implemented in Hungary's 2019 local elections, achieving several high-profile successes. Most opposition parties – on both the left and the far right – supported common candidates in the mayoral elections, leading to wins in 10 (an additional six) cities with county rights, the largest cities in Hungary (Political Capital 2019).Footnote 2 Although this gave the opposition credibility and momentum, it did not re-establish fair democratic contestation (Hegedüs Reference Hegedüs2019).

Scholarly research on the strategy's efficacy is mixed. For example, Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal's analysis of voting patterns in the US Congress describes both-ends-against-the-middle, one subtype of a unified opposition coalition, as a ‘deviant voting pattern’ (Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal2011: 6). A ruling unified opposition coalition can be especially unstable at the national level, where its disparate member parties need to maintain an effective coalition to prevent the plurality party from forming a minority government (Nikolenyi Reference Nikolenyi2009: 78–80). Such coalitions may also be difficult in a dominant-party system, where the single party seeking dominance is considered central to coalition formation (Sened Reference Sened1996: 360–361).

There are, however, reasons to think that local-level conditions may be more hospitable to this strategy. Mayors are executives and may not need to maintain a governing coalition to act on local issues; unsurprisingly, the position of mayor is the most desirable in local coalition negotiations (Laver Reference Laver, Mellors and Pijnenburg1989). This may create incentives for interparty cross-municipal cooperation, especially if contending parties agree to distribute candidates equitably across the country, guaranteeing each a reasonably similar number of mayoralties. In theory, this would allow those parties an equitable distribution of opportunities for developing national candidates and for disbursing resources allocated by local government.

There are also grounds to suggest that this strategy may work when local opposition candidates face democratic backsliding, or even outright competitive authoritarianism. As Robert Harmel and Kenneth Janda (Reference Harmel and Janda1994: 278) have argued, typically political parties ‘are conservative organizations and resist change’, which augurs badly for an atypical strategy such as ‘unified opposition’. They also argue, however, that external shocks – such as constitutional changes, changes in longer-term electoral prospects or events that challenge ‘confidence in the correctness or importance of key positions’ – may make parties open to fundamental change (Harmel and Janda Reference Harmel and Janda1994: 267, 270). We argue that democratic backsliding constitutes just this kind of shock. For vote-maximizing parties, it threatens ‘the terms of exchange in the electoral arena’, and for policy-oriented parties, it calls into question adherence to policy positions when democracy itself is at stake (Harmel and Janda Reference Harmel and Janda1994: 265). Empirical work by Jennifer Gandhi and Ora John Reuter (Reference Gandhi and Reuter2013) finds that, in multiparty authoritarian regimes with competitive elections, the emergence of opposition coalitions against the ruling party depends in part on party system institutionalization and harassment of the opposition; both are moderately high in Hungary's emergent hybrid regime. Historically, the most notable instances of this coalition type have occurred in Mexico against the PRI government (Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt2003) and in India, where Adam Ziegfeld and Maya Tudor (Reference Ziegfeld and Tudor2017) argue that opposition coordination plays a crucial role in defeating the dominant Congress Party. This practice has been especially durable in Mexico, albeit aided by the relative absence of stable ideology among the major national parties. Elections were most frequently lost by the PRI when subnational coalitions were formed by the largest opposition parties, PRD and PAN (Diaz-Cayeros and Magaloni Reference Diaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2001: 278–281). It has been more widespread at the gubernatorial level but is also seen locally since the 1990s (Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt2003; Giraudy Reference Giraudy2015). In Turkey, Orçun Selçuk and Dilara Hekimci (Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020) suggest that opposition parties in both local and national elections have coalesced around a democracy–authoritarian cleavage made salient by democratic backsliding.

How do these cross-national examples translate to the context of local politics in Central Europe? Overall, we are sceptical of the viability of coordinating united opposition coalitions in local mayoral races. First, despite the high-profile successes in Hungary's 2019 local elections mentioned above, there is no indication of how the fractured opposition will fare in governing. Likewise, there is little indication that this strategy worked in any but the largest cities, which are already predisposed to support the opposition. Even when agreements are reached, voters may vote against such a coalition. Jennifer Gandhi and Elvin Ong (Reference Gandhi and Ong2019) experimentally demonstrate that if a less favoured opposition candidate emerges in a unified opposition coalition, individual voters may defect from the opposition to a dominant party. This risk is real in Hungary, where the far-right Jobbik party's participation is numerically necessary. In Poland's May 2019 European Parliament elections, the opposition successfully negotiated an agreement to combat PiS but was still defeated (Rae Reference Rae2019). In either case, we might consider the failure to make such a coalition – organized or de facto – would probably result in fracturing the opposition vote. Second, Central European parties are generally under-institutionalized, especially opposition parties in dominant-party systems and especially at the subnational level (Gendźwiłł Reference Gendźwiłł2012).

One way we might see evidence of such coalitions would be through a reduction in the number of candidates. The logic is simple: if fewer parties support unique candidates, we would expect to see fewer in the race. Moreover, if local-level opposition coordination is a viable strategy in post-communist circumstances, then we should observe a positive relationship between the number of candidates and the dominant-party candidate's odds of victory. Dominant-party candidates should perform better when multiple opposition candidates are competing, indicating an absence of coordination among opposition forces. A weak or non-existent relationship would indicate that strategically limiting the number of candidates is not much help at the polls. This logic will be most powerful under single-round, first-past-the-post electoral rules. As discussed below, we expect that two-round electoral rules reduce the incentives for candidate coordination, allowing for an inverse relationship between the number of candidates and the dominant party's odds of success:

Hypothesis 1: The more candidates running for a mayoralty, the more likely the ruling party is to win.

Our remaining hypotheses concern conditions affecting dominant-party success in two-round systems. Extant scholarship suggests that this institutional variation should impact the possibility of opposition coordination because the second round can focus the contest into a race between the opposition candidate and the dominant-party candidate. Aurélie Cassette et al. (Reference Cassette, Farvacque and Héricourt2013) find variability in two-round French mayoral elections and suggest that different factors and electorates come into play between the two rounds. Broader studies of two-round elections at the presidential level find that having a majoritarian system, as opposed to a simple majority system, favours party alternation in government (Rakner and van de Walle Reference Rakner and van de Walle2009). A second-round election creates a clear opportunity for the opposition to overcome some of the coalitional obstacles to forming a cordon sanitaire against a threatening party.Footnote 3 If the opposition has credible fears that the ruling party aspires to a single-party dominant regime, they have greater incentives to overcome these obstacles. This leads to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: A dominant party's odds of victory decrease if a race reaches a second round.

As indicated above, the possibility of a second round should also affect the relationship between the number of candidates and the odds of ruling-party victory in two-round systems. The possibility of a second round limits the incentives for opposition candidates to cooperate and unify in the first round, which would lead us to expect more candidates entering races. How might this affect the dominant-party candidate's odds? In theory, at least, it could advantage the ruling-party candidate: Laurent Bouton (Reference Bouton2013) argues that the ‘Ortega effect’, in which opposition voters overestimate the chances of their candidate reaching a second round, may advantage political blocs with more unified support. Those voters may choose to support less viable candidates, assuming that they will have another opportunity to vote with their head.Footnote 4 On the other hand, it may hurt the dominant-party candidate's odds by the following logic. First, even if the possibility of a second round leads to more opposition candidates in the first round, vote-splitting among the opposition candidates as a group does not add to the votes needed for the ruling-party candidate to achieve an absolute majority and avoid a second round. Second, the first round may serve as a filter for opposition-candidate quality: the idea here is that the ruling-party candidate will face the strongest of the first-round candidates (Carey and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Carey and Polga-Hecimovich2006). The more candidates there were in that first round, presumably, the more likely the one that survives will be a strong candidate. Our final hypotheses encapsulate these arguments:

Hypothesis 3: In two-round systems, as more candidates contest an election, the odds of a dominant-party win decrease.

Corollary to Hypothesis 3: In two-round systems, as more candidates contest an election, the odds of a dominant-party win in the second round specifically decrease.

Data

Our data consist of panel local-level mayoral results for all municipal elections at the town level or higher in Poland and Hungary. Because Fidesz and PiS assume power nationally in different years – 2010 and 2015, respectively – we base our panel on the position of an election in the cycle of establishing regime dominance. In both cases, we include the local election immediately before the regime takes power nationally as a baseline panel (in Hungary, 2006; in Poland, 2014). We then include subsequent election results after national control is established, beginning with Panel 2. Table 2 shows the asynchronous distribution of panels across election years.

Table 2. Panel Election Alignment

We include all municipalities at the town level and higher in both countries. Our sample comprises 895 Polish and 345 Hungarian local government units. In Hungary, this includes all 345 towns (város) as of 2014. In Poland, we include all urban (miejska) and urban–rural (miejsko-wiejska) local government units (gmina).Footnote 5 Urban gmina comprise a single town/city, while urban–rural gmina consist of a town and villages within its orbit.Footnote 6 In both cases, status as a town (Hungary) or urban/urban–rural gmina (Poland) is determined administratively and not based on any particular population threshold. Data on village elections in Hungary and rural (wiejska) gmina in Poland are not included, as elections in these areas are not typically contested by national parties; instead, we focus on town and city politics exclusively.

Our dependent variable is whether the ruling-party candidate (PiS or Fidesz) wins a given municipal election. We only include cases in our analysis where PiS or Fidesz chooses to field a candidate; where they do not field a candidate, our dependent variable is coded as missing, so as not to bias the results. In other words, the dominant party should not be considered to have lost a race it did not contest. We have two independent variables of interest. To proxy pre-electoral strategic coordination, we use the number of candidates running for office in a given municipal election.Footnote 7 We also use a dichotomous variable indicating whether an election required a second round. Uncontested elections are included in our data. The data come from the respective national election agencies and have been consolidated into a panel data set.

We include several control variables to account for potential confounders. In national-level elections, the strongholds of PiS and Fidesz are typically described within the parameters of the urban–rural divide familiar from other examples of populist resurgence. Fidesz evolved as a party catering to rural voters and maintained this electoral strength as it achieved structural dominance (Knutsen Reference Knutsen2013), while PiS performs much worse in urban areas in national elections (Marcinkiewicz Reference Marcinkiewicz2018). Both parties are considered to have their base in small- to medium-sized municipalities that are less economically dynamic, whose residents are older on average and have lower levels of educational attainment. By contrast, the liberal opposition generally prevails in larger cities with expanding economies and younger, better-educated residents. We control for three factors often tied to populist party success. The first is municipal population, as resistance from urban centres has been prominent in challenges to dominant parties in largely (Scheiner Reference Scheiner2006), semi- (Diaz-Cayeros and Magaloni Reference Diaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2001) and un-democratic (Wallace Reference Wallace2013) contexts. The second is economic distress, operationalized as the local unemployment rate. The third is generational–cultural backlash, the idea being that support for illiberal populists is driven by a return to traditional values in the face of progressive cultural change, especially among older voters (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). We operationalize this as the percentage of the local population over 60 years old.

Finally, we include a dummy variable to control for the presence of a dominant-party affiliated incumbent in the race. Incumbency is generally considered advantageous for a candidate in any type of election, but research shows it to be especially valuable in mayoral contests (Freier Reference Freier2015; Holbrook and Weinschenk Reference Holbrook and Weinschenk2014). Blane Lewis (Reference Lewis2020) also finds that pre-election coalitions may not matter for incumbent mayors as much as for challengers; this indicates that an incumbent affiliated with a nationally dominant party may be especially well insulated against a united opposition coalition. In Poland specifically, Jarosław Flis (Reference Flis2018) argues that incumbency is advantageous in local elections, while in Hungary Stenberg (Reference Stenberg2018) finds that opposition incumbents make it substantively less likely for Fidesz to win mayoralties. The perceived strength of an incumbent becomes an important strategic calculation for potential candidates seeking election as mayor (Flis et al. Reference Flis, Gendźwiłł and Stolicki2018). Dominant-party incumbents may be especially advantaged in Polish and Hungarian mayoral elections due to the politicization of the media apparatus by the nationally dominant party (Turska-Kawa and Wojtasik Reference Turska-Kawa and Wojtasik2020).

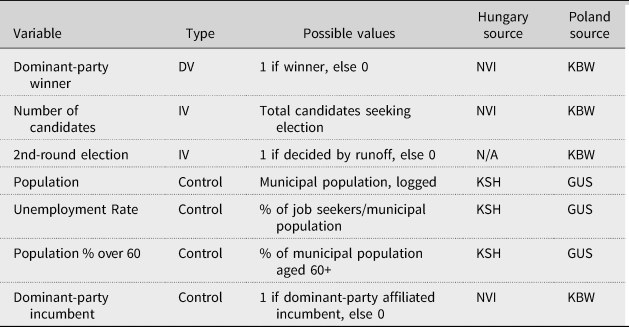

Control variable data come from the respective national statistical agency's subnational data sets; population uses logged electoral year estimates. Table 3 summarizes the variables.

Table 3. Variable Specifications

Notes: Variable type: DV = dependent variable; IV = independent variable. Hungary source: NVI = National Election Office; KSH = National Statistics Office. Poland source: KBW = National Electoral Office; GUS = Central Statistics Office.

To analyse these data, we use a panel logit model since our key dependent variable is dichotomous. We use a random effects model, as there is not sufficient variation within each case across time on all variables of interest (Bell and Jones Reference Bell and Jones2015). Random effects also capture differences between cities that do not vary systematically. Where appropriate, country and cycle fixed effects are included.

Limitations

Like all research based on observational data, our analysis is likely subject to omitted variable bias. To reduce this bias, we include both cycle fixed effects and, when results are pooled, country fixed effects. We use cycle fixed effects rather than yearly fixed effects because in the year of overlap (2014) there is little reason to expect that the international political environment would affect both countries systematically; instead, variation in party situation in 2014 (Fidesz in the second local election after regime establishment v. PiS running before achieving national success) would create more conflict than including yearly fixed effects would reduce.

There are also slight differences with the construction of the local government tier in Hungary and Poland. The urban gmina, which consists solely of one Polish municipality, and Hungarian város are directly comparable: they are local governments comprising single municipal units. However, urban–rural gmina differ. These gmina include not only a town but also several small surrounding villages. Thus, there is a possibility that voters in the surrounding villages behave systematically differently from voters in towns. We include these gmina because we do not want to miss political dynamics in the central towns; however, this comes at the cost of the dilution of ‘urbanness’, even if the urban–rural gmina are centred on a core municipality.Footnote 8

A second point regarding the data is our coding of party affiliation in Poland. The plurality of mayoral candidates in Poland's municipal elections run as independents. However, the unsystematic nature of how election data are recorded tends to obscure the influence of national party organizations, and thus magnify the visibility of independents. Independents are typically identified on election ballots under such names as the ‘The Electoral Committee of Voters of candidate so-and-so’ or ‘The Electoral Committee of Voters for a Better fill-in-city-name’. When a candidate is supported by a national-level party, the name of the electoral committee will often, but not always, reflect it: for example, ‘Electoral Committee Law and Justice’. The Polish Electoral Commission's official data also provide information regarding declared membership in a national party and support of a national party. Unfortunately, these data are not collected systematically. Often, the party membership and party support variables are missing, but the name of the electoral list clearly indicates a party connection. It can also happen that the electoral committee indicates an independent candidate, but the party membership variable declares an affiliation. Looking at only one of these three variables makes national party organizations seem much less visible at the local level than reading all three together would. In our coding, we take the most comprehensive approach. Specifically, we code a candidate as affiliated with a national party if: (1) she is a member of a national party; (2) she is supported by a party; or (3) she runs on a ballot listing the name of a national party. If a candidate meets none of these conditions, we code her as independent. In Hungary, while there is non-zero switching between independent and party-affiliated status, party affiliation among mayoral candidates is widespread, and this issue is less present in the data.

Results

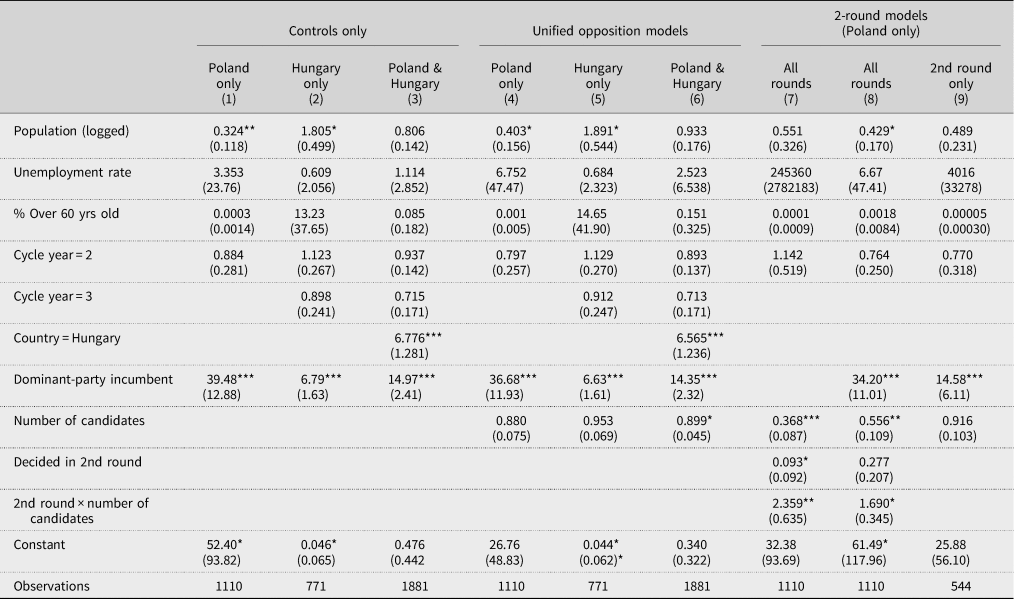

Table 4 summarizes our statistical analysis of the factors influencing dominant-party candidates’ odds of victory. For more intuitive interpretation, we present the odds-ratios – that is, the percentage change in the odds of victory for a unit change in a given independent variable (Online Appendix A reports the logistic regression coefficients). The models are organized into three groups, with country-specific subsets depending on the hypotheses under examination: a first set of baseline models with only the control variables included; a second set focusing on unified opposition strategies; and a third set examining two-round electoral systems.

Table 4. Odds Ratios (Dependent variable: win by dominant party).

Notes: Exponentiated coefficients; standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Considering only our control variables (Models 1–3), the evidence in Table 4 suggests differing degrees of local-level hegemony for Fidesz and PiS. In Poland, PiS has been unable to overcome its mobilizational disadvantages in larger cities. There is a statistically significant decrease in the odds of PiS winning a mayoral election associated with an increase in municipal population (the effect of other controls seems to be subsumed by population size). In Hungary, there is no such association with population size, which is surprising given the traditional urban strength of left-wing opposition parties against dominant-party regimes. The country fixed effects for Hungary are statistically significant and substantively large, indicating that the dominant party is much more likely to win in Hungary than in Poland. In both countries, the presence of a dominant-party incumbent is associated with a far greater likelihood of a dominant-party election win. Having a dominant-party incumbent in the race increases the odds of a dominant-party victory from anywhere between about 7 times (Models 2 and 5) and 40 times (Model 1).Footnote 9 This accords with the broader literature on incumbency in mayoral elections (Freier Reference Freier2015; Holbrook and Weinschenk Reference Holbrook and Weinschenk2014) as well as specific findings about incumbency in previous local Polish elections (Gendźwiłł and Żółtak Reference Gendźwiłł and Żółtak2014). These results confirm the basic trends in the descriptive data presented in Table 1 and Figure 2, which show the contrast in dominant-party success across both countries.

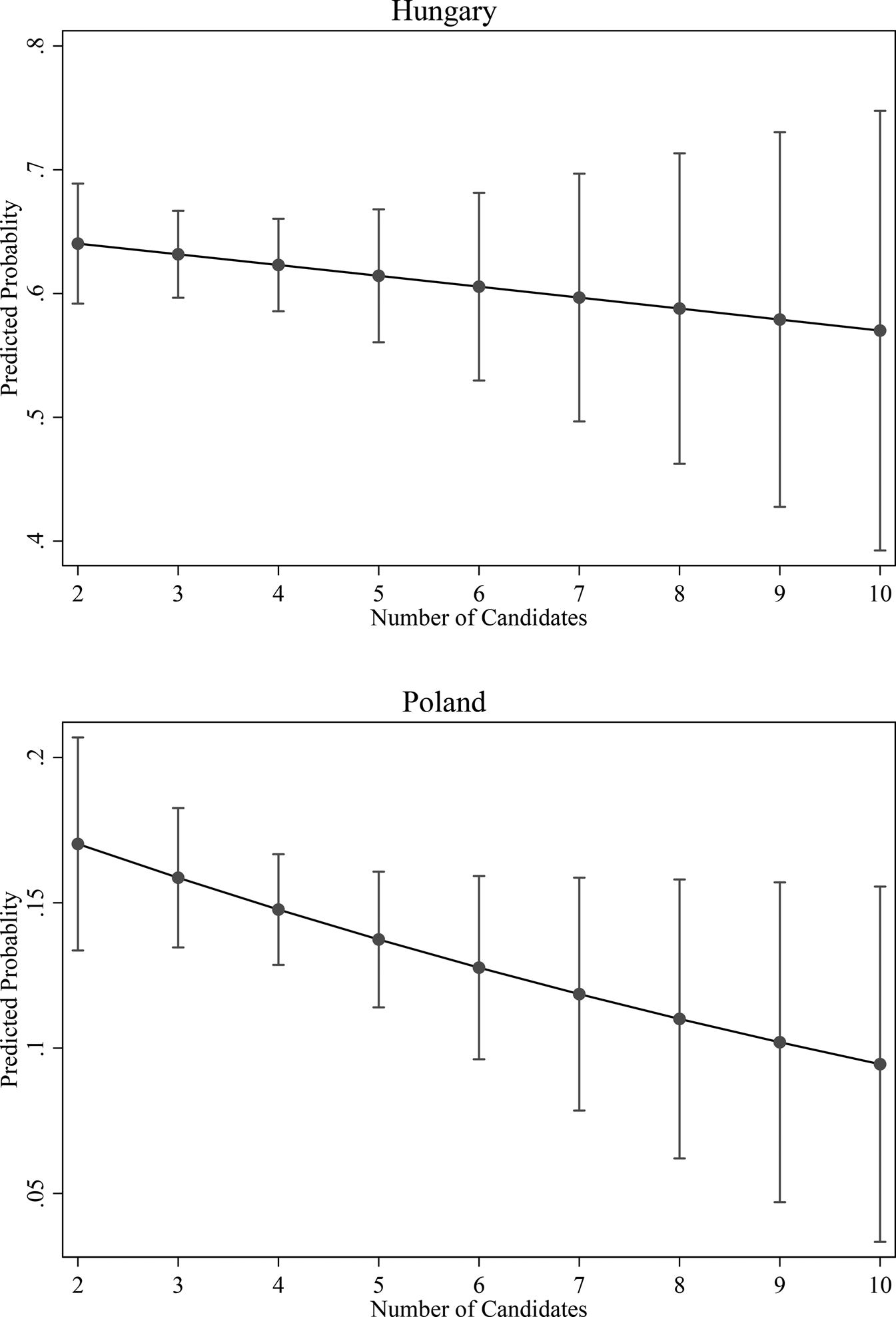

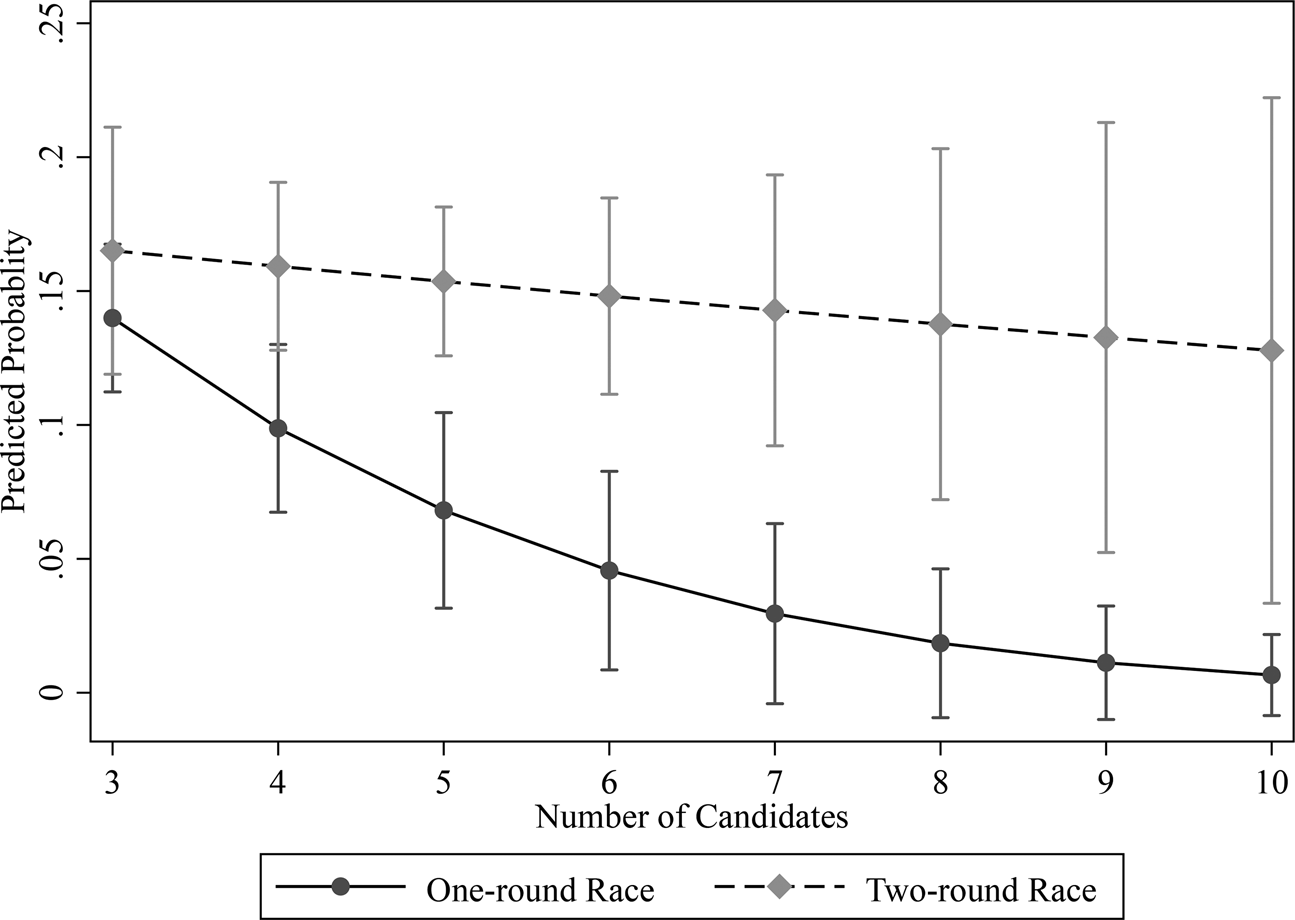

Models 4–6 analyse the efficacy of unified opposition strategies, as operationalized through Hypothesis 1. Only Model 6 shows a statistically significant relationship between the number of candidates and the dominant-party candidate's odds of victory; however, individual country models do not reach statistical significance.Footnote 10 Another way to visualize this relationship is in terms of the estimated probability of a dominant-party victory – as opposed to the change in the odds of victory, as we have done thus far (see Figure 3). Contra Hypothesis 1, Figure 3 shows a decreasing probability of dominant-party victory with more candidates (based on Models 4 and 5), though, again, it is not statistically significant. Because its single-round rules should most incentivize opposition candidate coordination, the lack of a relationship is most striking for Hungary (Model 5). This result could be either because of the advantages of Fidesz incumbency (the ‘Dominant party incumbent’ term) or because the under-institutionalization of opposition parties at the local level makes coordination too difficult. We suspect both are at play. Turning to Poland (Model 4), the lack of relationship between number of candidates and dominant-party victory is less surprising given that the possibility of a second round decreases the incentive for opposition coordination. In sum, Models 4–6 strongly suggest that strategic opposition coordination is insufficient to prevent the consolidation of dominant-party regimes at the local level.

Figure 3. Predicted Probabilities of a Dominant-Party Win by Number of Candidates (with 95% confidence intervals)

That dominant-party candidates do not benefit from facing a fractured opposition in Poland could indicate that electoral rules disadvantage dominant-party candidates, as Models 7–9 probe. These models add two independent variables to capture the effects of runoff rules. The first is a dummy variable indicating whether a race went to a second round (‘Decided in 2nd round’); it offers a straightforward test of Hypothesis 2, that a dominant-party candidate's odds of victory decrease if a race goes to two rounds because of the runoff's clarifying effect. Second, an interaction term, ‘2nd round × number of candidates’, allows us to address Hypothesis 3 and its corollary, as explained below.

Regarding the clarifying effect of a second round, Models 7 and 8 provide qualified support for Hypothesis 2. In Model 7, the odds of a dominant-party victory decrease significantly in races that go to a second round (variable: ‘Decided in 2nd round’): for such races, the odds of dominant-party victory are reduced by 90.7%. When the presence of a PiS incumbent candidate is accounted for (Model 8), however, this effect is more attenuated, and it falls just below the 0.05 threshold of statistical significance (p = 0.086). This leaves open the possibility that the second round may offer a clarifying effect, especially considering the significance of the interaction term, as discussed below.

The evidence supports Hypothesis 3: as the number of candidates in two-round systems increases, the odds of a dominant-party win decrease. In Model 7, the effect of the number of candidates is negative, substantively large and statistically significant at the 0.001 level, when considering the effect of elections decided in the first round. For each additional candidate in the race, the odds of a dominant-party win decrease by 63.2%. Including the ‘Dominant-party incumbent’ variable – which we saw earlier to be very powerful – in Model 8 moderates the effect somewhat but it remains highly statistically significant and substantively important. Figure 4 illustrates the interaction between number of candidates and election round in terms of estimated probabilities. It suggests no evidence for the ‘Ortega effect’ in Polish elections – that is, that opposition candidates overestimate their chances of advancing and thereby make it easier for the dominant party to win in the first round. Instead, our results suggest that increasing the number of candidates simply divides the vote among more options, thereby reducing the dominant party's chances in the first round. In short, there is no penalty to having more opposition candidates.

Figure 4. Predicted Probabilities of a Dominant-Party Win in Poland (by number of candidates and rounds, with 95% confidence intervals)

In the corollary to Hypothesis 3, we hypothesized that more candidates in the first round may decrease a dominant-party candidate's odds in the second round specifically by ensuring that she faces a strong challenger (the filter effect). In Model 8, the interaction effect between the number of candidates and the second-round variable shows a statistically significant difference in how the number of candidates affects races decided in the first round versus those decided in the second: specifically, the impact of the number of candidates on second-round races is much smaller, and is, in fact, effectively zero (see Figure 4).Footnote 11 To determine whether the number of candidates retains an effect within second-round elections, Model 9 examines only those Polish elections decided in the second round. We find that the number of candidates does not significantly impact the likelihood of PiS winning. Thus, we do not find strong support for a filter effect.

We draw the following general conclusions from this analysis. First, since the impact of the number of candidates is much higher in races that do not reach the second round, there appears to be little cost to an especially appealing independent or opposition candidate for each additional candidate in the race; she can still win in the first round. Second, in elections reaching the second round, the number of candidates seems not to play a major role: this indicates that the opposition is not weakened by being more fractured before the election. We conclude therefore that, once the election has reached the second round, the number of candidates does not impact the likelihood of the dominant party winning in either direction. In sum, the negative relationship between the number of candidates and the dominant party's chances of victory in all Polish elections appears to be related to the clarifying effect of a second electoral round regardless of the number of candidates. While Model 9 does not demonstrate a clear filtering effect, it remains plausible that a larger number of candidates increases the likelihood of the strongest opposition candidate advancing, but that the strength of this candidate is not impacted by the number of candidates.

Conclusion

In both Hungary and Poland an elected right-wing party has changed laws, rules and institutions to ensure that they maintain electoral control. Both remain successful nationally, each handily winning their most recent national parliamentary election. This article has investigated whether local-level mayoral elections might constitute an arena for opposition politicians to challenge the dominant PiS and Fidesz parties and, if so, how. Our findings indicate that, given the under-institutionalization of local parties and the strong advantages of dominant-party incumbents, opposition success at the local level is difficult to achieve if it must rest on strategic electoral coordination alone. Our findings do suggest that dominant parties are more vulnerable in local races based on two-round electoral rules than in simple majority ones. This institutional variation offers a plausible explanation for why PiS has been less successful than Fidesz in extending its dominance to local government.

Our findings have implications for party politics in both countries. In Hungary, absent an incumbent to coalesce around, the strategy of forming a unified opposition coalition may not be a panacea, despite considerable media attention. National parties have embraced this strategy for the 2022 parliamentary elections, agreeing that they will field a joint candidate for prime minister and party lists after Fidesz pushed through reforms designed to make a looser coalition impossible (Bayer Reference Bayer2020). It is possible, however, that it may be preferable to maintain a diverse opposition so that voters feel a greater sense of choice. In Japan, attempts to form a broad opposition coalition through strategic withdrawal of candidates ultimately reduced voter interest in the election and brought about a dominant-party victory (Scheiner et al. Reference Scheiner, Smith, Thies, Pekkanen, Reed and Scheiner2016).

That said, these findings should not be seen deterministically. We would not suggest to opposition parties in hybrid regimes that a unified opposition coalition is a failed strategy, rather that they should not expect automatic success. Opposition parties need to balance cooperation and their own, individual electoral prospects. The value of incumbency in local elections means that individual parties also have to consider the potential ramifications of ceding control to another opposition party. Given the instability in the Hungarian party system, especially among left parties, party survival is a salient concern for party leaders. Consequently, even when cooperation might make an opposition electoral victory possible in a particular race, it still may be a losing proposition for an individual party's long-term viability.

In Poland, too, the opposition should be wary of any pre-election coalition formation given the variance in electoral structures. Our findings show that PiS is substantively less likely to win elections that go to the second round and elections with more candidates. However, our findings raise questions about the mechanisms by which the possibility of a runoff helps opposition candidates. The evidence suggests that runoffs reduce the costs of a fractured opposition (the clarifying effect), but we do not find clear evidence that they help filter out weaker opposition challengers. Future research should investigate the reasons behind these findings, both specifically in the Polish context but also in larger comparative work. A practical takeaway is nevertheless clear: if an increase in number of candidates is associated with decreasing likelihood of dominant-party victories, there is little need for disparate opposition parties to spend time and resources trying to negotiate painful concessions for coalitions that might otherwise be politically unpalatable. Investigating the effects of candidate quality in dominant regime perpetuation would be a promising avenue for future research. Additionally, future research can examine why Poland's PiS has not adopted some of the more aggressive subnational strategies of Fidesz. While these strategies would undermine subnational democracy, they would enable the further consolidation of their party's control.

Finally, to consider Hungary and Poland in terms of broader trajectories of democratic backsliding, our findings point to underlying weakness for PiS. Fidesz has extended its dominance to local politics in concrete ways, eliminating a primary avenue for opposition parties to build up credibility to challenge a dominant-party regime. PiS has had no such success. Descriptive statistics show that it wins many fewer races than Fidesz, and we see no statistically significant cycle effect in Poland to suggest the regime is consolidating over time. Poland seems more likely to follow historical examples where threats to a dominant party emerge after achieving subnational electoral success, demonstrating their viability to challenge the regime. Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski emerging as the strongest challenger to Polish President Andrzej Duda in the 2020 Polish presidential election is perhaps the best example of this potential. Naturally, it is important to remember that democratic backsliding is not only a question of how competitive elections are, especially municipal ones. In particular, Fidesz's and PiS's tactics show backsliding is also a question of the independence of the judiciary and media. Even if the playing field of municipal politics remains level, it will not immediately correct the national field's tilt. However, just as backsliding is often a chipping away at democracy's foundations, so too might a weakening of dominant-party influence begin locally before it reaches the top.

Supplementary material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please go to https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.12.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Bence Rimóczi, Amanda McCabe, Marisa Connell, Dylan Harriman and Alejandro Alvarez for research assistance and Bryn Rosenfeld for helpful comments.