Populist radical right (PRR) parties are one of the most researched party families in the literature on European party competition and political conflict structures. The burgeoning literature devotes considerable attention to the disproportionate influence of PRR parties on the programmatic offering of their competitors (e.g. Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter and Kriesi2021), hardly explained by the moderate electoral success which members of this party family typically achieve. Yet, despite the focus on the mainstreaming of PRR appeal by other parties, we know less about the trade-offs involved in the mainstreaming of PRR parties themselves as they transform over their life cycle (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Lange and Rooduijn2016). This is important since understanding change in the programmatic appeal of PRR parties determines the extent to which they become less of a pariah party over time. Here, the dynamic of competition in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) reveals more pronounced changes over time than in the more institutionalized Western European party systems (Pytlas Reference Pytlas, Herman and Muldoon2019).

We focus on the role of the media which allows these parties to face the trade-offs involved in broadening their appeal beyond their core constituency. PRR parties compete in an increasingly differentiated media environment, where online media outlets and particularly social media is growing in importance for the media diet of the citizenry. Communication research has explored the extent to which a transformed media environment and specific types of media outlets may carry or even reinforce populism and nativism (e.g. Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Fawzi and Larsson2017; Hameleers and Vliegenthart Reference Hameleers and Vliegenthart2019; Krämer Reference Krämer2017; Zulianello et al. Reference Zulianello, Albertini and Ceccobelli2018) as the two key elements of the programmatic appeal of PRR parties. However, this line of literature has largely existed separately from the literature on party competition, which discusses the incentives to change party appeal.

We propose bridging the literature on party competition and political communication to explore change over time in the programmatic appeal of a PRR party throughout its life cycle: Jobbik – Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom). We take Jobbik as a representative case of the PRR party family in the post-communist region, an ‘archetype of the populist radical right party in Central and Eastern Europe’ (Pirro Reference Pirro2015: 106). Although initially Jobbik achieved early and exceptional success by regional standards through a nativist appeal, the party adopted a more mainstream programme soon after its entry to parliament in 2010 in the hope of increasing its electoral support. However, the success of this strategy remained limited and after the third Fidesz two-thirds electoral victory, its long-term president, Gábor Vona (2006–18) resigned in the aftermath of the 2018 elections. Since then, Jobbik has seen the rise of intra-party conflict and a decline in both its electoral support and its visibility in the press.Footnote 1 Studying Jobbik in this period thus allows us to trace the party's programmatic appeal over its lifetime. The case of Jobbik illustrates the specific issues the transformation of PRR parties entails in the CEE context.

Although programmatic change is generally a risk for parties, it comes with particular challenges for PRR parties. They combine people-centred, anti-establishment rhetoric with nativism to maintain their reputation of uncompromising ideological purity (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Lange and Rooduijn2016). Yet, as they are confronted with isolation in the party system and reach the electoral ceiling of PRR rhetoric, it becomes appealing to adjust their message and bring it closer to the preferences of the median voter. While targeting the centre is potentially attractive to all parties in a Downsian framework (Wagner Reference Wagner2012), the moderation of PRR parties hinges on nativism: unlike mainstream parties that form their appeal based on a diverse set of issues without particular emphasis on any single one of them, for PRR parties, nativist issues play a key role. De-emphasizing nativism carries the risk of losing the support of their core electorate, but may allow PRR parties to achieve higher vote shares overall and eschew the stigma of a pariah party.

In previous research, change in PRR programmatic appeal is conceptualized as positional shifts across issue dimensions (Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2017), an expansion of the diversity of issues emphasized in party platforms (Bergman and Flatt Reference Bergman and Flatt2020) or a shift in narrative frames (Pytlas Reference Pytlas, Herman and Muldoon2019). Notwithstanding their merit, none of these approaches considers the distinction between populism and nativism important in explaining shifts in the appeal of PRR parties over time, mostly because they implicitly assume that emphasis on populist and nativist messages is part of the same dimension and the two ‘move together’. The argument is most explicitly formulated by Tjitske Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Lange and Rooduijn2016), who identify the moderation of PRR parties’ nativist and populist appeal as two distinct but equally important dimensions of mainstreaming. We propose a previously underexplored mechanism, according to which the mainstreaming of the appeal of the PRR is captured by a shift in emphasis from nativism towards populism. Increasing the salience of populism to the detriment of nativism should help PRR parties to develop a more ‘moderate’ profile without abandoning their core electorate. In this regard, we contest the assumption that by mainstreaming their appeal, PRR parties equally abandon populist and nativist appeals. The empirical analysis of Jobbik's communication in partisan media outlets, press releases and Facebook posts illustrates that nativism simultaneously declines and transforms, allowing populism to become the defining element of the party's programmatic appeal.

Our approach innovates both substantively and methodologically. By bridging the party competition and political communication literature, we bring the focus on PRR parties and CEE party competition to the literature on political communication. We enrich the literature on party competition with the focus on media strategies and outlet-level differences in parties’ programmatic appeal. Methodologically, we study this dynamic through an exceptionally long time span, from 2006 to 2019, and across different sources. To study Jobbik's appeal over time, we collected a unique data set that brings together partisan sources, press releases and Facebook posts. To our knowledge, no other analysis of the communication strategy of a PRR party to date covers a similarly long time span across a set of sources as diverse as these. We innovate on the prevalent approach in the literature, which infers party positions based on a single source, be that expert surveys or party manifestos. Using a dictionary approach to party messages, we put the agency of PRR parties at the centre of the analysis and discuss the constraints and opportunities provided by the media environment and electoral competition.

In what follows, we outline the role of the media in alleviating the tension PRR parties face as they become more successful and have to appeal to a diverse set of preferences. After introducing the type of data we analyse and our dictionary-based approach to studying the development of populist and nativist appeals, we present empirical evidence of static and over time differences between media channels, as well as the role of supply- and demand-side factors in the evolution of Jobbik's programmatic appeal. The conclusion summarizes the findings and places them in the broader literature on PRR parties.

Theoretical considerations

Two models of challenger politics in CEE

We start by introducing the distinction between what we consider the two prevalent models of challenger party politics in the CEE region (Engler et al. Reference Engler, Pytlas and Deegan-Krause2019; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2014; Stanley Reference Stanley and Kaltwasser2017; Učeň Reference Učeň2007). The first of these models is nativist mobilization by PRR parties, the second anti-establishment mobilization by centrist populist parties.

According to Cas Mudde (Reference Mudde2007: 15–23), PRR parties are defined by their nativist appeal. These parties combine nativism with populism and authoritarianism, the two additional dimensions that characterize the appeal of the PRR party family.Footnote 2 Nativism, as the ideology of the nation state, ‘holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (“the nation”) and that non-native elements (persons and ideas) are fundamentally threatening to the homogenous nation-state’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2007: 19). In formulating a nativist appeal, PRR parties explicitly exclude groups that they consider non-native. Although both nativism and populism are often mobilized by the same PRR actors, populism is a thin-centred ideology (for the analytical distinction between the two, see e.g. Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017), defined by the interaction of two distinct components: people-centrism and anti-elitism (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). People-centrism, an appeal to the ‘will of the people’, is an often-used trope in a range of programmatically different calls to mobilize. Here ‘people’ ‘can refer to the common or ordinary people, the people as plebs; to the sovereign people, the people as demos; and to the culturally or ethnically distinct people, the people as nation or ethnos’ (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017: 359). While nativism and populism might both appeal to the ‘people’, nativism entails a more restrictive ethnic definition of the people. Unlike nativism, populist mobilization formulates an encompassing message, without targeting or excluding groups based on pre-political traits. Additionally, populism links people-centrism with anti-elitism by accusing elites of betraying the will of the people.

While PRR parties achieved notable success after the transition by combining nativist and populist mobilization, after EU accession a particular brand of populist mobilization emerged in the CEE region (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2014; Stanley Reference Stanley and Kaltwasser2017) – so-called centrist populism (Engler et al. Reference Engler, Pytlas and Deegan-Krause2019). Centrist populist parties mobilize against the political elite as a whole, formulating an anti-elitist, pure form of populism, ‘almost completely unencumbered by ideological constraints’ (Učeň Reference Učeň2007: 54). Whereas, in the case of PRR parties, nativism acts as a host ideology and forms a well-identifiable core of their programmatic appeal, the host ideology of centrist populist parties varies considerably (Engler et al. Reference Engler, Pytlas and Deegan-Krause2019). The success of centrist populist parties in CEE demonstrates the ability of these parties to make salient use of anti-establishment/populist ‘thin’ supply even if they link it with ‘thick’ ideological appeals placed within the mainstream. PRR parties that have achieved a certain level of success but are confronted with the limited availability of new voters sympathetic to their nativist agenda might be inspired by the success of this alternative brand. One strategy to outgrow the limits of a nativist appeal is to change the ‘thick’ ideology of nativism while keeping the ‘thin’ populist elements of people-centric and anti-establishment mobilization intact. Such a strategy runs counter to the assumption that populism and nativism need to develop similarly in processes of moderation (e.g. Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Lange and Rooduijn2016).

Differentiated media landscape and strategic messaging

So far, we have introduced the distinction between the two models of challenger politics in the CEE region and indicated why centrist populism might appeal to already established PRR parties. In this section, we discuss the role of the media in allowing the party to rebrand its nativist ‘thick’ ideology and target more centrist voters. We build on literature that discusses how parties communicate with voters in CEE in their attempt to augment and stabilize their electorate, a literature which has explored two different avenues. First, an increasing body of work demonstrates that parties use their organizations to communicate with voters (e.g. Tavits Reference Tavits2013). Second, when they communicate via media channels, parties mobilize the appeal of their candidates and organizational brand (Pirro Reference Pirro2015; Werkmann and Gherghina Reference Werkmann and Gherghina2018). We take a step further and explain the mechanisms that lead to higher and more differentiated electoral appeals in the case of communication via the media by a PRR party.

Specifically, we argue that the segmentation between the audience of the different media outlets means that parties may formulate two different appeals simultaneously: one targeted at their core electorate, and the other at the general public. This is in line with existing qualitative evidence suggesting that parties act strategically and consider differences in the audience of platforms in their online campaigns (e.g. Kreiss et al. Reference Kreiss, Lawrence and McGregor2018). For PRR parties, a differentiated media landscape provides the opportunity to target audiences selectively, and simultaneously deploy nativist messages for their base while formulating an appeal to new voters with a less nativist appeal.

To understand how PRR parties build their appeal strategically, we need to enrich the purely ideational understanding of populism with the role of populist communication strategies. While the two are sometimes discussed as competing approaches to the study of populism, we consider them complementary and follow Hanspeter Kriesi (Reference Kriesi2014: 364; also see Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007), who argues that ‘populist ideology manifests itself in the political communication strategies of populist leaders. … As an expression of the populist ideology, populist communication strategies may be used to identify the populist ideology empirically.’

This leads us to adapt the argument about parties’ strategic communication across media channels so that it emphasizes both aspects of the PRR appeal: PRR parties may weight the thin ideology of populism and the thick ideology of nativism differently in their communication on different platforms. This can be translated directly into our first expectation: the key dimension distinguishing media outlets is how far they target core supporters as opposed to the general electorate. We argue that PRR parties attempting to moderate their programmatic appeal – here Jobbik – rely on more partisan media outlets to keep their supporters on board with nativist messages. Having a firmly established presence in the relatively isolated radical right milieu allows the party also to formulate a more inclusive, populist message for the general electorate in the mainstream media. Hence, our first hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1: The more a media channel targets the party's core supporters, the more nativist the party's communication on this channel.

In addition to static differences, our argument about media strategies as an expression of moderation entails that the shift over time is not characterized by the same trend and pace across platforms. Two different processes contribute: on the one hand, to maintain their credibility, we expect mainstreaming by PRR parties to be a gradual and continuous process that takes place over a longer time. On the other hand, maintaining the loyalty of existing voters requires regularly deploying nativist messages – for instance, to fire up the base before elections. This strategy should result in short-term fluctuations in the emphasis on these messages. While both the long-term trend and the fluctuation shape the level of nativism, we argue that we are most likely to observe bursts of nativist messages on platforms targeting existing supporters – for example, in partisan media outlets. In contrast, in outward communication that Jobbik engages in to change its appeal, we are more likely to see gradual and continuous change.

Hypothesis 2: The more a media channel targets the party's core supporters, the more the dynamic of nativism fluctuates.

PRR parties’ appeal in their electoral context

In the previous sections, we introduced the two models of challenger politics in CEE as well as the role of a differentiated media landscape in allowing PRR parties to balance the two forms of appeal. In this section we will discuss the broader context of electoral competition to identify the incentives PRR parties face in forming and adjusting their appeal. We argue that the extent to which PRR parties maintain their nativist appeal depends on the interaction of media channels with supply- and demand-side considerations.

According to our baseline expectation, as they mature, PRR parties moderate their nativist appeal throughout their lifetime. A key moment in this regard is entry to parliament, when the institutional logic of parliamentary politics puts these parties under pressure both to take a position on a broader set of issues and to break with movement-based mobilization (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt, Katz and Crotty2006: 287). Although most successful PRR parties broaden their appeal beyond nativism (Bergman and Flatt Reference Bergman and Flatt2020), we suggest the dynamic of the process is not only a function of their organizational features but depends on the broader context of electoral competition (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1989), including both supply- and demand-side factors.

We highlight two such factors that we argue shape PRR parties’ media strategies. First, potential supply-side competition from another party targeting nativist voters with a programmatically proximate offer may push PRR parties to stop moderating. PRR parties are then forced to re-emphasize nativism and distinguish themselves from their competitor. This may occur because of the emergence of radical splinter parties or because centre-right parties appease the radical electorate. Here, Hungary represents an extreme case: although not having a cordon sanitaire between the mainstream and the PRR is somewhat typical for CEE (e.g. Pytlas Reference Pytlas, Herman and Muldoon2019), the main centre-right party in Hungary, Fidesz, increasingly targeted nativist voters after the 2015 so-called migration crisis (Gessler et al. Reference Gessler, Tóth and Wachs2021). Notably, by 2017, Fidesz overtook Jobbik in being the party furthest to the right in the Hungarian party system in cultural terms (Pirro et al. Reference Pirro2019: 3). Fidesz's move was part of a longer-term strategy of accommodating some of Jobbik's proposals (Enyedi and Róna Reference Enyedi, Róna, Wolinetz and Zaslove2018; Gessler and Kyriazi Reference Gessler, Kyriazi, Hutter and Kriesi2019; Pirro Reference Pirro2015; Pytlas Reference Pytlas2016), which put Jobbik under pressure to distinguish its stance from the rhetoric of the government and defend its electoral base. In this regard, being embedded in the radical right media landscape might allow Jobbik to appeal differently to its core electorate to renew its nativist reputation. Accordingly, we expect that:

Hypothesis 3: As Fidesz becomes more nativist, Jobbik increases the salience of nativism in media channels targeting the party's core supporters.

Second, from a demand-side perspective, the appeal of PRR parties should also depend on the potential to gain new voters. With their populist appeal, PRR parties are in principle well-positioned to target voters disappointed with other parties and political elites. Distancing themselves from nativism means they can not only target right-wing but all anti-establishment voters. Here, the high level of ideological polarization (Vegetti Reference Vegetti2019) and dissatisfaction with the government in Hungary should sustain this dynamic; public opinion polls consistently find that more voters wants a change in government than those willing to vote for the parties in opposition. This constitutes a central anti-/pro-government divide and provides particular opportunities for Jobbik, as it refused to cooperate with former governing parties of both political camps. Not being associated with past governments potentially allows Jobbik to mobilize not only voters disappointed with the government but also those who did not vote in the past.Footnote 3 As we argued previously, a central strategy in this regard is to form a broad appeal in general media outlets. Consequently, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4A: When the share of undecided voters is higher, Jobbik decreases the salience of nativism in media channels targeting the general electorate.

However, as Markus Wagner (Reference Wagner2012) convincingly argues, parties evaluate demand-side opportunities differently, depending on the parties’ strength in the electorate. For large parties, moderate positions enable them to appeal to a wide electorate. For smaller parties such as the PRR, emphasizing issues on which they have extreme positions allows them to distinguish their profile (also see Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994). While Wagner does not include the media in his model of issue selection, a segmented media market allows parties to differentiate their appeal further. Thereby, parties can distinguish themselves among their supporters without necessarily alienating undecided voters. Introducing differences across media channels leads us to expect that when Jobbik is smaller, the party emphasizes nativist issues in outlets targeting its core electorate. In contrast, when Jobbik is more popular, we would expect a lesser emphasis on nativism across all media channels:

Hypothesis 4B: When the share of undecided voters is higher and Jobbik is less popular, the party is more likely to rely on its nativist message in media channels targeting its core electorate, but not in media channels targeting the general electorate.

The implications of the supply- and demand-side dynamic give rise to competing pressures on PRR media strategies. While Fidesz targeted its core electorate, Jobbik faced an increasing pressure to present a more inclusive, anti-Fidesz appeal. Faced with these countervailing forces, we argue that a differentiated media landscape allows PRR parties to ‘square the circle’ by tailoring their appeal to both partisan and centrist voters. In what follows we describe the media context which makes such a strategy viable in the Hungarian case.

The PRR in the Hungarian media landscape

Compared with other CEE countries, the Hungarian media landscape is considered remarkably clientelistic (Örnebring Reference Örnebring2012). High political dependency allowed both the left and right to establish their own media empire, for example, by dividing up available radio licences among stations loyal to them. The new media law adopted in 2010, and the restructuring of ownership in its aftermath, increased the political dependence of the media (Bajomi-Lázár Reference Bajomi-Lázár2015) and led to the dominance of right-wing media outlets. In this context, the radical right has established its own media environment independent of mainstream media outlets (Jeskó et al. Reference Jeskó, Bakó and Tóth2012). The radical right media is embedded in a subcultural milieu where, next to political and infotainment media outlets, other actors are present, such as national rock bands, clothing shops and even organic food shops. To conceptualize the extent of differentiation of the radical right media network, József Jeskó et al. (Reference Jeskó, Bakó and Tóth2012) cite the pillarized society model of Arend Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1968). Relying on their analysis, we map the programmatic appeal of Jobbik in the two most prominent partisan media outlets.

Based on network analysis, Jeskó et al. (Reference Jeskó, Bakó and Tóth2012) find an isolated, self-referential radical right online network, with most websites established after 2006. They identify infotainment websites as key instruments for Jobbik to feed its messages to its supporters. Two of these websites stand out in their analysis as the source of the messages that subsequently spread in the network: Kuruc.info and Barikád.hu. Launched in 2006, Kuruc.info has been the most prominent source of hate speech in Hungary. The page features sections devoted to so-called ‘Holocaust fakes’, ‘Roma criminality’, ‘anti-Hungarianism’ and ‘politician criminality’. Kuruc.info enjoys remarkable popularity: in 2010, it was the third-largest online political news source with around 60–90,000 unique visitors per day. Although Jobbik did not acknowledge its links to the website, the portal has been one of the most devoted allies of the party due to its affiliation with Előd Novák, a politician in Jobbik's leadership.Footnote 4 Thus, we decided to include this source, in part due to its prominence in the radical right online network, in part due to the overlap between its readership and the party's core electorate.

Unlike Kuruc.info, which has an independent identity and loyal supporters, the second website Jeskó et al. (Reference Jeskó, Bakó and Tóth2012) identify, Barikád.hu, was established as a party news website. Published as a weekly magazine in print between 2010 and 2017, in addition to daily online coverage, it is primarily financed by the party foundation of Jobbik. When the distance between Kuruc.info and Jobbik started to increase, Barikád.hu went through a change as well: pre-2012 posts were deleted, and the platform was rebranded as Alfahír.hu. The website has become a right-wing news site, aiming to provide a consistent flow of information to party supporters but falling short of the radicalism as well as the popularity of Kuruc.info. Its news sections and editorials feature Jobbik prominently in a positive light. Given the close connection between Alfahír.hu and the leadership of Jobbik, the party has considerable influence over what is published on this platform.

While Jobbik is only partly able to influence what is published by these sources, both Kuruc.info and Alfahír.hu represent the media channels most clearly targeting the party's core supporters. In addition to them, we also trace the programmatic appeal of Jobbik in the party's press releases and on Facebook. While in the press releases Jobbik targets the general electorate via the press, the target audience of social media posts is less clear. On the one hand, we may suspect that Facebook serves as a medium of direct communication (Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Fawzi and Larsson2017; Krämer Reference Krämer2017) between the party and its relatively young voter base. On the other hand, given the diversity of potential audiences on social media – not only sympathizers but also journalists and other media professionals – Facebook might also be a tool for the party to inform a broader audience. In the latter case, Facebook serves the same purpose as the press releases issued by Jobbik and distributed by traditional media outlets: it broadcasts the party's message to the general public.

Data and methods

We propose studying programmatic change as a shift in emphasis. More specifically, we study changes in the salience (i.e. relative emphasis) of the elements associated with the populist and nativist ideology in Jobbik's messages in different media outlets over time. While studying programmatic change based on salience neglects positional shifts, the latter are relatively unlikely to occur, especially in the case of radical parties (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018).

Techniques of quantitative text analysis have two advantages vis-à-vis other approaches in measuring populist and nativist communication, both of which have key importance in our research design (Meijers and Zaslove Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021). First, they are uniquely able to capture shifts in salience. Secondly, they allow us to estimate the variance between different texts, and consequently between different media outlets. Our approach builds on recent papers that use quantitative text analysis to measure issue emphasis and specifically populism with dictionaries (Bonikowski and Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016, Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2019; Hameleers and Vliegenthart Reference Hameleers and Vliegenthart2019; Harrison and Bruter Reference Harrison and Bruter2011; Hunger Reference Hunger2020; Pauwels Reference Pauwels2011; Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011). However, we go beyond existing work by, first, carefully constructing a comprehensive populism dictionary that is specific to the Hungarian context, second, by assembling a much larger text corpus that includes multiple sources and covers the party throughout its life.

We construct dictionaries to trace the three key concepts of our analysis: anti-elitism, people-centrism and nativism. In line with the definition of populism (see above), and with the recent literature on populism as a latent construct (e.g. Meijers and Zaslove Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021), we classify a document as populist when terms from both the anti-elitist and the people-centrist dictionary are present. We start the dictionary construction by translating the terms used in the dictionaries of the above-cited studies. We tested them by sampling texts that contained the terms. We kept only entries that were present in at least two of the corpora we examine and indeed appeared in a context associated with the concept they aim to measure. We complemented these terms with two additional sources. First, we constructed a list of terms based on the Manifesto Corpus (Merz et al. Reference Merz, Regel and Lewandowski2016): we selected all electoral manifestos by Jobbik and extracted the terms that distinguish issues close to our key concepts from other issues.Footnote 5 Second, we complemented the final list with some context-specific terms, mostly referring to historical revisionism, which were not present in the previous lists or the manifestos. To validate our dictionary, we tested its performance against a stratified sample of 250 hand-coded documents, randomly selected from all five corpora. The dictionary is slightly better for nativism (F score = 0.91) than for populism (F score = 0.82). Online Appendix A presents the final terms and additional details on the dictionary we constructed.

To convert these documents into measures of emphasis on populism and nativism, we follow the approach of Bart Bonikowski and Noam Gidron (Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016, Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2019), and rely on a dichotomous distinction in classifying them: a document is nativist if it includes at least one word from our nativism dictionary, a document is populist if it includes at least one word each from our anti-elitism and our people-centrism dictionary.Footnote 6 While less precise than a relative approach that measures the proportion of nativist words within a document, we believe the dichotomous distinction provides a more accurate assessment of the overall corpus, since it mitigates differences in the length and character of documents which we describe in the next paragraph. Although not every document that contains, for example, one of the terms associated with nativism may strictly be a ‘nativist document’, we believe that even occasional nativist references activate nativist ideology. In Online Appendix D we show the distribution of documents using an alternative, proportional measure.

For the actual analysis, we collected almost 60,000 documents that reflect Jobbik's communication. We obtained all articles on Kuruc.info and Alfahír.hu which mention Jobbik in the title or main text at least once. We collected all press releases the party had issued from the Hungarian national press service (Országos Sajtószolgálat), which publishes press releases by parties and organizations. In addition, we also collected all Facebook posts by the official account of the party (JobbikMagyarorszagertMozgalom) and the account of the party president Gábor Vona (vonagabor) from CrowdTangle.Footnote 7 We selected the period from 1 February 2006, the time when the first press releases by Jobbik were issued and just before the party's first electoral run, up until 15 March 2019. Next to the Jobbik-specific corpora, we also collected Fidesz press releases from the same source for the same period, to test our hypothesis on supply-side dynamics. The five corpora differ in their time period,Footnote 8 size and characteristics (e.g. average length of documents) ranging from roughly 3,500 posts on the Facebook page of Gábor Vona to almost 22,000 articles on Kuruc.info (see Table 1 in Online Appendix B). We believe this represents the most comprehensive analysis of Jobbik's communication so far.

Finally, we use the measures to conduct a time series cross-sectional regression analysis to explore the drivers of change. In this part of the analysis, we model the quarterly share of documents we classify as nativist. The linear model includes panel corrected standard errors (Beck and Katz Reference Beck and Katz1995), and assumes a panel-specific first order auto-correlation AR(1) process, which corresponds to the lag structure of the nativism series on each platform. We include platform fixed effects and model nativism as a function of Jobbik's populism, organizational development (pre-parliament, in-parliament, after the migration crisis), the party's popularity (mean value of the figures from Ipsos, Medián, Publicus, Republikon, Tárki), the share of those in the electorate who indicate they have no party to vote for (mean values from Tárki and Závecz Research Center), and Fidesz’s nativism based on the party's press releases. Jobbik's popularity, the share of undecided voters, and Fidesz’s nativism are included with a lag.

Results

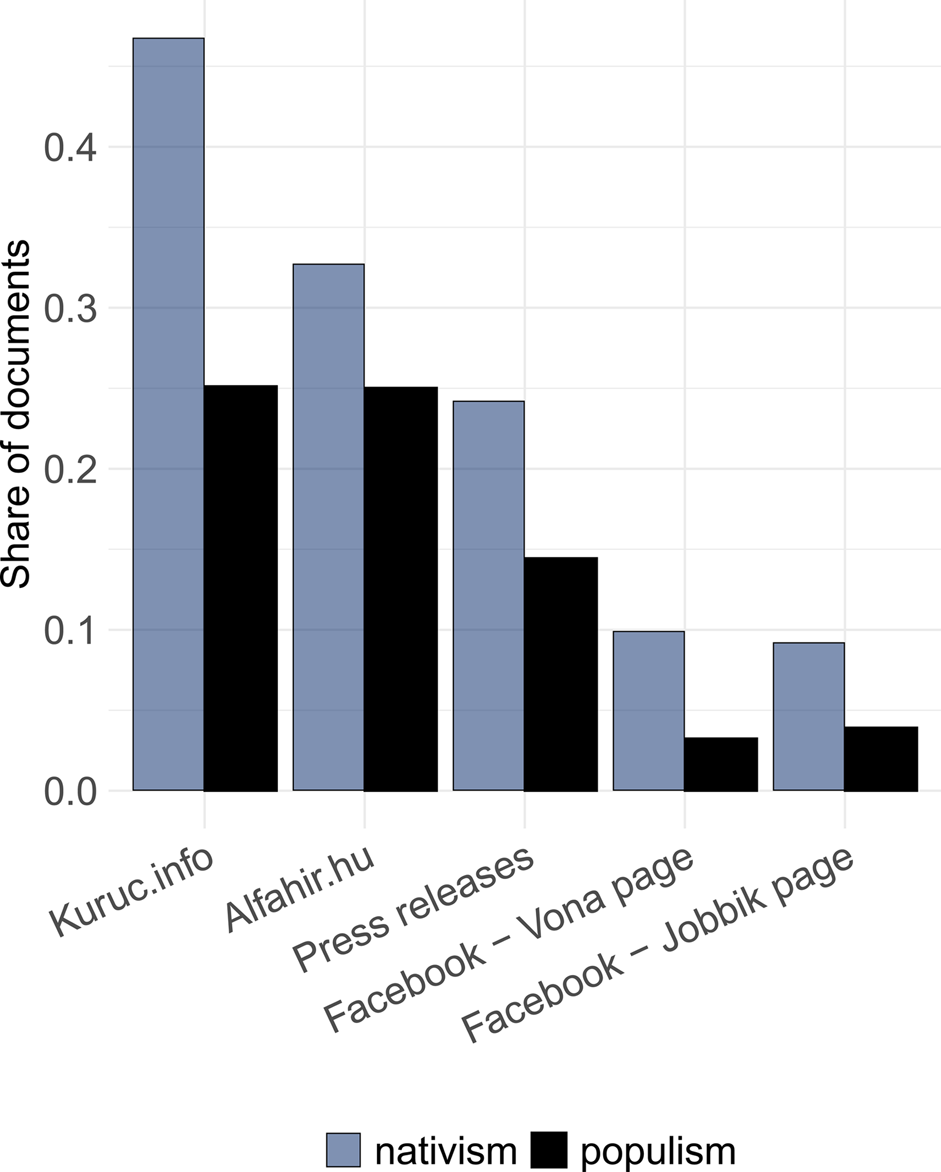

Our key argument refers to the variation in the amount of nativist and populist messages across platforms. To test this expectation, we start by examining the level of nativism and populism based on our document classification. Figure 1 presents the average share of nativism and populism by platform:

Figure 1. Documents with a Nativist and Populist Appeal on Each Platform

As Figure 1 shows, the level of nativism is higher than the level of populism in all the five channels we examine, but platforms vary according to their targeting of Jobbik's core supporters. In line with H1, Jobbik is most likely to rely on its nativist appeal in the two partisan media outlets, primarily on Kuruc.info, which is somewhat more nativist than the party-funded Alfahír.hu, which in turn resembles the press releases. Facebook substantially lags behind. Populism follows the variation of nativism: it reaches its highest level in the partisan media outlets, followed by the press releases, and finally by Facebook. The low levels of nativism and populism on Facebook indicate that the party uses the social media platform to reach out to a diverse audience, which is not necessarily attracted by nativist and/or populist messages. Overall, the gap between the level of nativism and populism is smallest on Alfahír.hu.

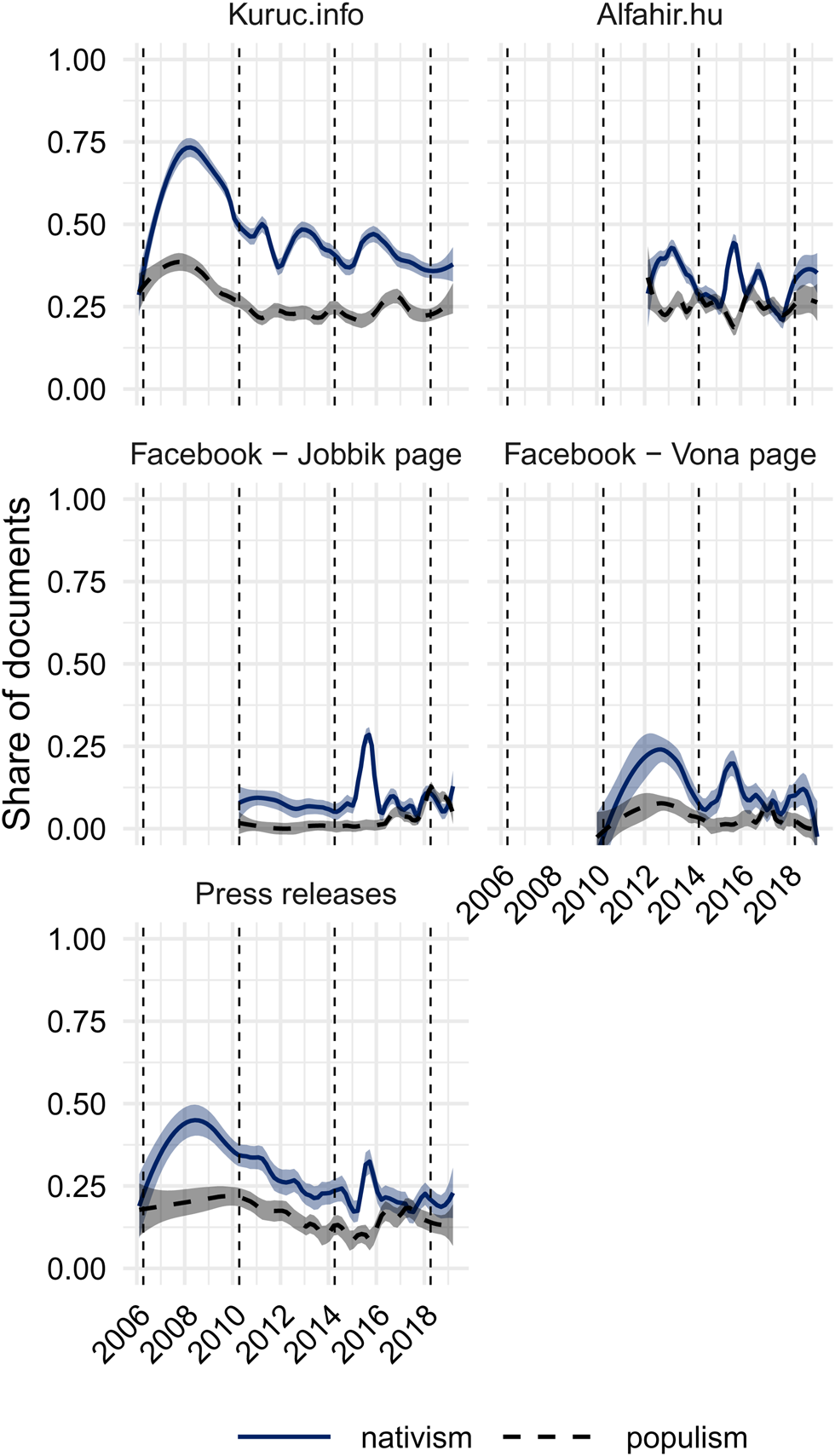

We now turn to variation over time to test our second hypothesis. To do so, Figure 2 presents the share of documents we classify as nativist or populist, across the different platforms, over time.

Figure 2. The Share of Documents Over Time with a Populist or Nativist Appeal on the Different Platforms

Note: The lines represent the LOESS smoothed estimates for all documents within a corpus and its associated 95% confidence interval. The dashed vertical reference lines represent national parliamentary elections.

In line with H2, the two partisan media outlets and the two Facebook pages show the fluctuation of nativism and the more stable level of populism. As the coverage of Kuruc.info reveals, the extent to which Jobbik relied on nativism declined prior to entering parliament, with some shorter-term fluctuations throughout the period. Although the coverage of Alfahír.hu starts later, the pattern reveals similar short-term fluctuations of nativism, with populism less prone to change. This also shows that the overall level of nativism on the different platforms varies in part due to their age. On Facebook we observe more fluctuation in nativism on the account of Vona than on the official account of the party. Press releases follow a different dynamic, characterized by a gradual decline in nativist and populist mobilization followed by relative stability after parliamentary entry.

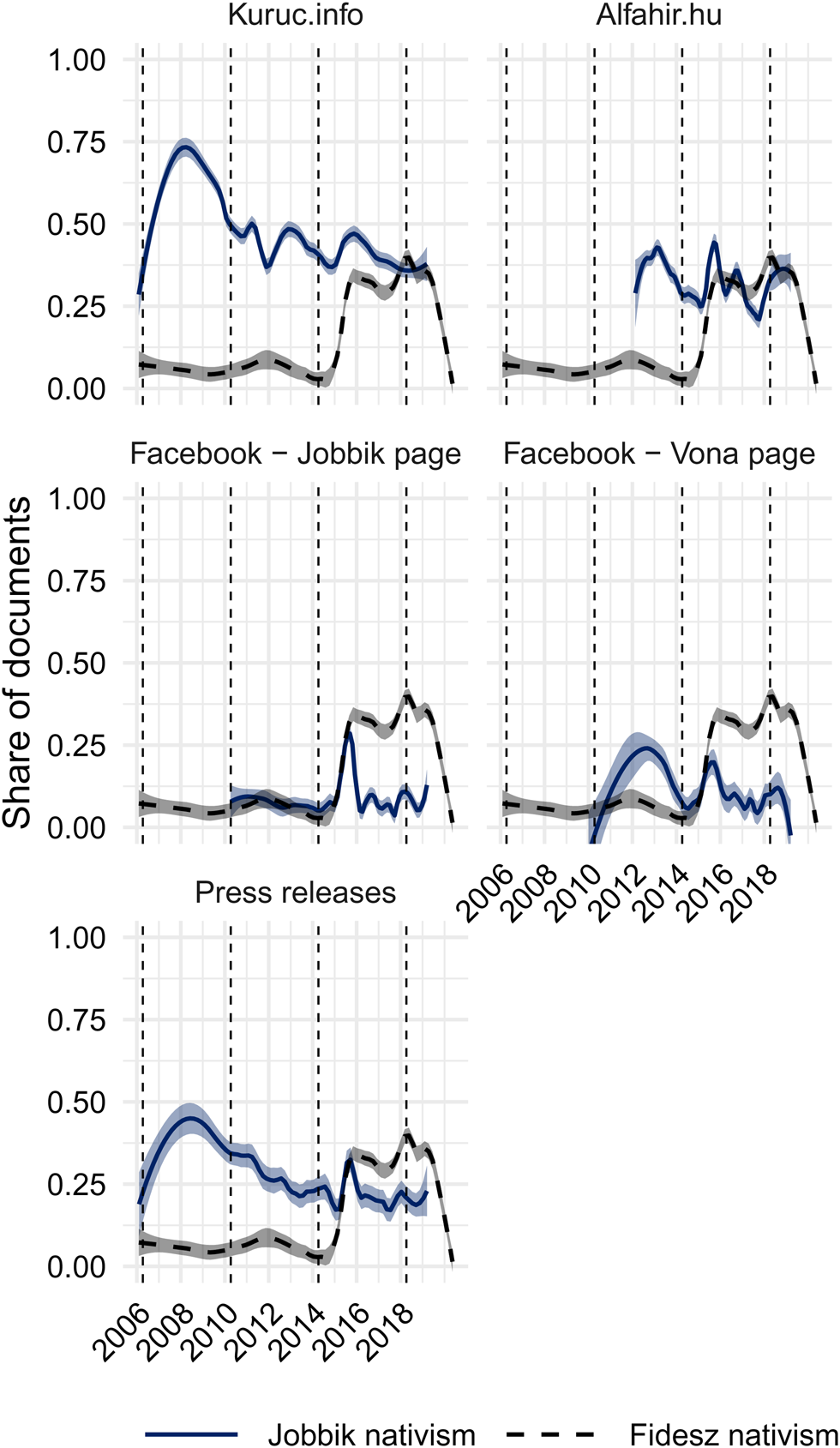

The level of nativist mobilization only partially follows the electoral calendar. Before the 2014 elections, Jobbik toned down its nativist appeal as part of a campaign to appear more moderate associated with the leadership of Vona that became known as the ‘cuteness campaign’. In contrast, before the 2018 election, Jobbik (re-)mobilized its nativist appeal on Alfahír.hu and Facebook, but the pre-election rise in nativism remains more modest than the relative peak of nativist mobilization in the pre-2010 period before Jobbik entered parliament. In parliament, the peak of nativist mobilization corresponds to the so-called migration crisis in the second half of 2015. This was the period during which Fidesz took a nativist turn. Figure 3 shows Jobbik's nativism across platforms parallel with the level of nativism observed in Fidesz's press releases during the same period.

Figure 3. Over Time Share of Documents with a Nativist Appeal on the Different Platforms Compared with the Share of Nativism in Fidesz's Press Releases

Note: The lines represent the LOESS smoothed estimates for all documents within a corpus and its associated 95% confidence interval. The dashed vertical reference lines represent national parliamentary elections.

As the figure shows, during this time, Jobbik's nativism radically increases across virtually all platforms. However, the phenomenon was short-lived, and by the second half of 2016 populism and nativism became similarly important on all platforms except Kuruc.info. While we are not suggesting that Jobbik mobilized in nativist terms only for strategic reasons in response to Fidesz, the temporal overlap between the two suggests supply-side interactions at least during this brief period.Footnote 9 When looking at the overall period of the evolution of Jobbik's appeal, we take the difference in the dynamic of nativism between the partisan outlets and Facebook on the one hand, and the press releases on the other hand as evidence of H2.

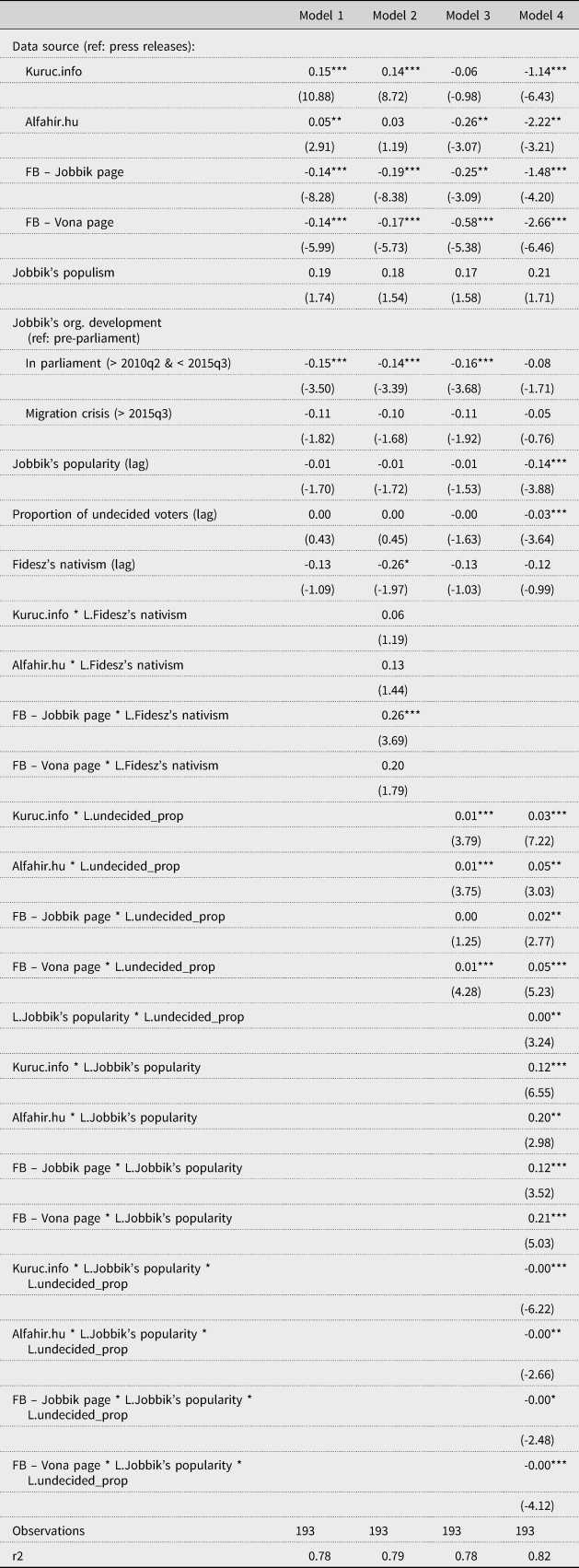

These results show that the main change in Jobbik's programmatic profile is a decrease in nativism over time. To model the drivers of this change, we now turn to the regression analysis. Table 1 shows the results of the model we introduced in the data and methods section.

Table 1. Level of Nativism in Jobbik's Appeal (quarterly level, TSCS regression)

Note: t statistics in parentheses; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Model 1 presents our baseline model. The model confirms the platform differences the descriptive analysis has shown: compared with the press releases, the level of nativism in the partisan media outlets is higher, while on Facebook it is lower. We take this as evidence of H1. The model also confirms our baseline expectation: throughout its life cycle, but particularly after the party enters parliament, the level of nativism in Jobbik's appeal declines. Controlling for these factors, the model shows that contrary to the assumption of some of the previous literature (e.g. Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Lange and Rooduijn2016), there is no statistically significant relationship between the level of populism and nativism in Jobbik's appeal. In other words, the variation of populism does not predict the variation of nativism; the party distinguishes the two in its messages. In terms of supply and demand, the baseline model shows that Jobbik's nativism does not linearly follow Fidesz's nativism, the party's popularity or the proportion of undecided voters in the electorate.

However, the baseline model estimates average effects across all platforms. To test H3, H4A and H4B, we conduct further analysis on platform-specific, differential reactions to supply- and demand-side incentives. Model 2 estimates the interaction effect between Fidesz's nativism and the platform. Although, as the model shows, Jobbik appears to be more likely to react to Fidesz's nativism on the party's official Facebook page than in the press releases, the size of the effect is too small to draw substantive conclusions (see the marginal effects in Online Appendix B, Figure 1). Fidesz's nativism escalates in the aftermath of the migration crisis, but as Figures 2 and 3 have already shown, Jobbik only responds with nativist mobilization for a brief period and soon returns to the previous mixture of nativist and populist messages. As a result, we are not able to confirm our supply-side hypothesis H3 unequivocally.

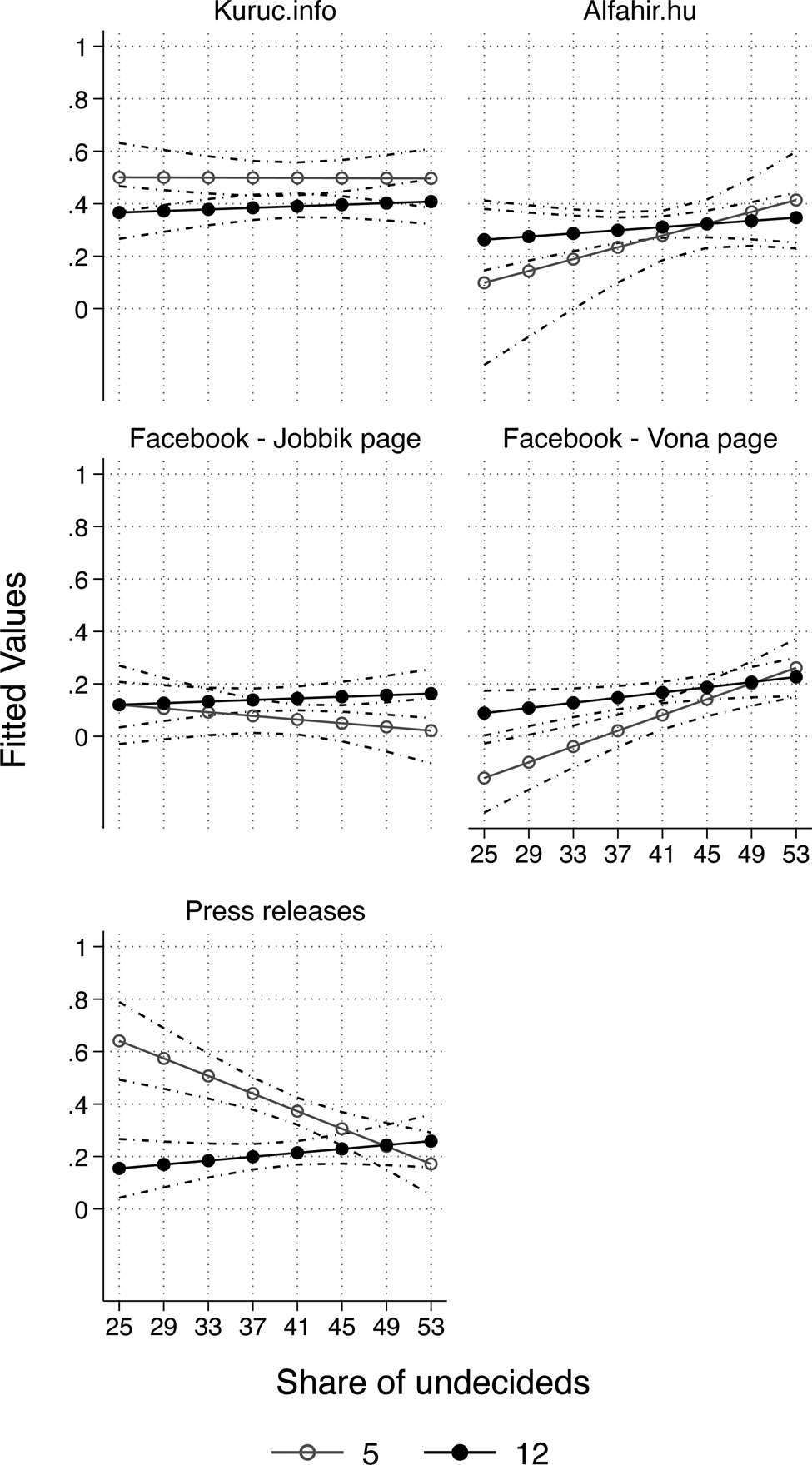

To test the demand-side effects, Model 3 and Model 4 present our estimates of variation in Jobbik's reaction to undecided voters as a function of the media channel and as a function of the party's popularity. In line with H4A, Model 3 shows that the level of nativism on the partisan media outlets and Vona's Facebook page is higher than in the press releases when the share of undecided voters increases. However, the effect size is once again too small to draw substantive conclusions (see Online Appendix B, Figure 2), possibly because the relationship is also moderated by the popularity of the party. We test H4B with a three-way interaction between the party's popularity, media channels and the share of undecided voters. As Model 4 shows, the interaction is statistically significant. To ease its interpretation, Figure 4 presents the corresponding marginal effects plots with values estimated for a popularity level of 5, respectively 12% (the variable ranges from 0.22–15.16%), across the range of undecided voters in this period:

Figure 4. Marginal Effects: Jobbik's Nativism on the Different Platforms as a Function of the Share of Undecided Voters and the Party's Popularity

Note: The marginal effects figure is estimated based on the three-way interaction shown in Model 4 in Table 1.

In line with our hypothesis, the results show that Jobbik is more likely to adjust its level of nativism in response to the share of undecided voters when the party is smaller. Once the party's popularity reaches a certain threshold, the level of nativism becomes independent of the share of undecided voters. If the share of undecided voters increases while Jobbik is less popular, the party is not only more likely to rely on nativism on Alfahír.hu, and Vona's Facebook page, but also radically decreases nativism in the press releases to appeal to the general electorate. The gap independent of Jobbik's popularity is actually largest for the press releases, suggesting that moderation in response to undecided voters mostly happens when communicating with the wider public. On Kuruc.info and the party's Facebook page, the dynamic of nativism appears to be independent of undecided voters even when the party is small. Overall, we take this as evidence of H4B.

Conclusion

In this article, we examined programmatic change throughout the lifetime of Jobbik, one of the archetypical examples of a PRR party in CEE. As we discussed our results along with the development of the Hungarian party system over the past years, readers may have noted that the case study design limits our conclusions to the Hungarian context. The Hungarian context and the case of Jobbik allowed us to map the media strategy of a PRR that achieved its breakthrough earlier than similar parties in many other countries. Due to the formal and informal characteristics of the institutional setting (namely a strongly majoritarian electoral system and a dominant party shifting to the radical right), Jobbik confronted the dilemma of mainstreaming its appeal in starker terms than perhaps other PRR parties have to face. While this context allowed us to highlight a previously underexplored mechanism of the PRR differentiating its appeal, we believe the phenomenon is similar in other contexts. In fact, the rise of alt-right media networks in contexts as diverse as the US, Germany and Slovakia points to dynamics similar to the one we have documented.

Despite the limitations of studying the dynamic in a single case, we believe our article contributes to two strands of literatures: political communication and party competition. We believe our article makes at least two key contributions. First, we highlight the importance of platform differences for the literature on party competition. Namely, they allow PRR parties to navigate between the two models of challenger politics in CEE. Our results show that, having the opportunity to differentiate its message, Jobbik appeals to the nativism of their core supporters as well as to the populist demand among the general electorate. Contrary to previous studies, which conceptualize mainstreaming as entailing a decline of both nativism and populism as two complementary facets of the appeal of PRR parties (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Lange and Rooduijn2016), our results show that mainstreaming is not a uniform process, but contingent on which groups the different platforms target. The ability to rely selectively on nativist mobilization allows Jobbik to call on its core supporters, even as it moderates its nativist appeal in messages formulated for the general electorate.

Second, we outline to which factors Jobbik's differentiated emphasis on nativism responds. We highlight the role of demand and supply factors that have been less present in the literature on political communication. Our results show that despite the tremendous supply-side pressure due to the nativist turn of Fidesz, Jobbik only briefly mobilized in nativist terms in the aftermath of the migration crisis. We believe nativist mobilization in this period remained short-lived because, following the majoritarian incentives in the Hungarian party system, Jobbik needed to find coalition partners to compete against Fidesz. Nativism undermines its coalition potential, and maintains its status as a pariah party, whereas a shift towards centrist populism makes the party more acceptable as a partner. Generally, Jobbik appears more responsive to demand-side opportunities such as the share of undecided voters, especially in times when the party is not electorally popular. We also show that Jobbik is more likely to target undecided voters in non-nativist terms on those platforms where the party formulates an appeal to the general electorate.

Our analysis shows that even prototypical PRR parties, such as Jobbik once was, change their appeal in response to a combination of supply- and demand-side incentives. However, we do not believe that Jobbik has become a moderate party that has left its nativist agenda behind. On the contrary, we show that nativism lives on in media channels targeting its core electorate and its fluctuations show that it is regularly deployed to mobilize its base. Nevertheless, strategic reasons push the party to rely increasingly on populism at the expense of nativist mobilization. While this move came with electoral costs for the party's popularity (see Online Appendix B, Figure 3), it was sufficient for it to become accepted as a member of a broad opposition coalition targeting Fidesz and thereby helped Jobbik to overcome its pariah status. One should, however, note that the party has not (yet) been in government, therefore a definite judgement on the extent to which it has abandoned its nativist ideas cannot yet be cast.

Overall, we hope the conceptual apparatus and the methodological approach this article puts forward – namely the study of parties’ programmatic appeal across multiple platforms and over a long period of time – will provide a helpful resource for future research that considers additional cases and builds on our arguments.

Supplementary material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.28.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andrea Ceron, Katjana Gattermann, Sophia Hunger, Swen Hutter, Matthias Kaltenegger, Seongcheol Kim, Heike Klüver, Andrea Pirro, Matthew Stenberg, Kristóf Szombati, the anonymous reviewers and participants at workshops and conferences for helpful comments on previous versions of this article. We presented earlier versions at a symposium organized by Cosmos in Florence, at the Party Congress Research Group Workshop in Glasgow, at the Political Science Colloquium of the Freie Universität in Berlin, at the Berlin Brandenburg Political Behavior Colloquium and at the European Politics Working Group of the University of California, Berkeley. Endre Borbáth would also like to acknowledge funding by the Volkswagen Foundation.