In his speech at the dawn of the third millennium, Romano Prodi (Reference Prodi2000), then president of the European Commission, claimed that the ‘[EU has] forged a model of development and continental integration based on the principles of democracy, freedom and solidarity, and it is a model that works’. Indeed, the EU entered the twenty-first century with remarkable achievements. The launch of the euro, the big-bang enlargement towards post-communist countries, and expanding neighbourhood policies in Europe’s outer periphery solidified its position as a sui generis power in international politics (Leonard Reference Leonard2005; Reid Reference Reid2005). The EU became a centre of attraction for countries in its inner and outer periphery in their quest to construct a liberal democracy and a market economy (Schimmelfenning and Sedelmeier Reference Schimmelfenning and Sedelmeier2005; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005). Recently, however, the situation changed dramatically. The euro’s devastating crisis, the weakening of the liberal democratic ethos in member countries following the spectacular rise of Eurosceptic nationalist-populist parties, and foreign policy failures vis-à-vis the Middle Eastern and Ukrainian crises cast growing doubts on the EU’s standard-setting capabilities in regional and global governance (Menon Reference Menon2014; Phinnemore Reference Phinnemore2015; Whitman and Juncos Reference Whitman and Juncos2014). Finally, the ‘Brexit’ vote may also have dramatic implications for the future of the European integration project (Niblett Reference Niblett2015). The EU model is clearly not working as originally envisaged by the European elites, since the EU finds itself in a stalemate in its response to new challenges. Considering this dramatic shift, we will address two critical questions: How do the recent multiple crises impact the EU’s transformative power over its inner and outer periphery? What accounts for the EU’s declining appeal and rising illiberal practices in several member and candidate countries?

Our objective is to make two main contributions to the literature. First, as Jan Zielonka (Reference Zielonka2014) points out, we have various theories of European integration, but no comparable analytical frameworks to account for disintegration or the dynamics of a progressively fragmented Europe. The dominant literature mainly deals with the achievements and limitations of EU conditionality (Graziano and Vink Reference Graziano and Vink2006). An extensive body of research deals with the mechanisms through which conditionality works in the EU’s relations with target countries. Both interest-based rationalist perspectives (Börzel and Risse Reference Börzel and Risse2000) and norm-based constructivist accounts concentrating on the diffusion of ideas (Börzel and Risse Reference Börzel and Risse2009; Christiansen et al. Reference Christiansen, Jørgensen and Wiener1999) offer compelling explanations for the EU’s policy, political and polity impact on member and candidate countries. Beyond the extended versions of ‘goodness of fit’ arguments, alternative approaches put domestic ‘preferences and beliefs’ at the forefront (Alpan and Diez Reference Alpan and Diez2014; Mastenbroek and Kaeding Reference Mastenbroek and Kaeding2006). These perspectives’ analytical utility notwithstanding, given recent global political developments, it appears that these approaches do not put any particular emphasis on the global political economy mechanisms of the EU’s declining appeal on third countries due to the inadequate attention they give to the international order’s changing dynamics (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2014; Webber Reference Webber2014). Considering this conceptual and empirical lacuna, we offer a global political economy perspective that complements the existing literature by adding the mutually inclusive interaction of European-level dynamics and global transformations based on a push-and-pull framework. The first part sketches the details of the proposed framework; the second applies it to the Hungarian and Turkish cases. The third offers a comparative analysis of democratic regression in both countries, and the final part concludes the article.

The Push-and-Pull Model of the EU’s Declining Transformative Power

The 2008 global financial crisis represents a watershed in the political economy of contemporary capitalism (Helleiner Reference Helleiner2010; Krugman Reference Krugman2012). The crisis was not the first shock that the world economy experienced in the neoliberal era, but it was certainly the most devastating one since the Great Depression. Contrary to previous economic crises during the 1990s and early 2000s in the global periphery, the recent financial crisis erupted at the centre of global capitalism (Öniş and Güven Reference Öniş and Güven2011). The sub-prime crisis in the US economy affected the European economies more deeply than any other corner of the world. In the short term, the crisis spread throughout the transatlantic economies, the bedrock of free market economy and liberal democracy. What is important here is that the global crisis led to the bifurcation of global governance along the lines of liberal market economies and models of state-led strategic capitalism, both accompanied by a distinct set of political institutions (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2010; Kagan Reference Kagan2008). The increasing fluidity and disorder in global governance paved the way for the emergence of a new set of push as well as pull factors, which dramatically undermined the EU’s transformative influence.

Push Factors

The EU’s declining appeal is closely associated with the ‘multiple crises of the Union’. These started with the identity crisis of the early and mid-2000s due to the constitutional stalemate, continued with the economic and financial crises of post-2008 and culminated in the refugee crises, which gathered momentum in early 2015. Added to these are security threats due to consecutive terrorist attacks in several EU countries. The growing sense of insecurity within the EU embodies several critical political implications.

The push factors weakening the EU’s transformative capacity have two interrelated dimensions. The first is correlated with the poor economic performance that has led to unfulfilled promises of the European project, especially after 2008. Most commentators and policymakers agree that the euro crisis is the most compelling challenge in the history of European integration (Matthijs and Blyth Reference Matthijs and Blyth2015; Zielonka Reference Zielonka2014). When first launched, the euro project was conceived not only as an economic instrument to deepen a single market and to position the euro as an alternative reserve currency vis-à-vis the US dollar, but it was also perceived as a strong leverage to consolidate European political identity and solidarity. Furthermore, economic benefits had been utilized as strong incentive tools that underpinned the effectiveness of EU conditionality on target countries.

The management of the crisis, however, has undermined the economic attractiveness of the European project. In the initial phases, the core European countries, notably Germany, framed Southern Europe’s crisis as the outcome of irresponsible domestic policies and urged, for instance, Greek leaders to rely on their own means to deal with it. Conversely, countries in the periphery accused the European core of remaining ignorant of the crisis’s systemic nature that stemmed from the euro area’s institutional flawed fundamentals, triggering a vicious cycle of ‘blame games’ (Hall Reference Hall2012). Once it became apparent that Southern European countries had neither the capacity nor the resources to halt the crisis, the German-led troika (European Commission, European Central Bank, IMF) programmes were put into implementation, a step considered too little too late and insufficient to fix the euro’s structural problems (Jones Reference Jones2015).

The EU’s flawed crisis management strategy had devastating consequences for the EU’s economic might and political cohesion. The prioritization of excessive austerity packages by core member states eroded the social fabric of crisis-ridden EU members and amplified the ‘peripheralization of southern countries’ (Gambarotto and Solari Reference Gambarotto and Solari2015). The manner in which the EU dealt with the euro crisis also represented a powerful blow to the very notion of democracy (Watkins Reference Watkins2012). Indeed, the replacement of elected politicians with appointed technocratic governments in Greece and Italy struck a sensitive nerve and further aggravated the ‘democratic deficit’ debates (Matthijs Reference Matthijs2014: 102). The public opinions in these countries increasingly questioned the EU’s solidarity ethos, as they felt punished by core members and EU institutions, leading to a growing sense of alienation. The crisis, in turn, consolidated the core–periphery divide in the EU. Central and Eastern European countries and Southern European members felt themselves pushed progressively further into the periphery (Bonatti and Fracasso Reference Bonatti and Fracasso2013). As Erik Jones (Reference Jones2015) put it, the European crisis was ‘over-determined’, and inadequate analysis of the problems’ multiple and interlinked nature resulted in Europe’s ‘muddling through’ (Blyth Reference Blyth2013). Furthermore, the EU’s inability to ensure economic recovery and the sluggish growth rates after 2008 decreased the appeal of the EU as a source of wealth and prosperity. For instance, the average growth rate in 2010–14 remained 1 per cent in the EU and 0.7 in the eurozone, which in turn decreased its role in shaping the preferences of member and candidate countries, especially for those in the European periphery.

The second dimension of the EU’s weakening transformative power concerns the crisis of internal solidarity, which gradually amplified problems with the credibility of its commitment and the EU’s normative paradoxes. It has long been claimed that the EU is a distinct actor in international relations, thanks to its ‘normative power’. Without necessarily resorting to hard-power instruments, the ‘EU’s ability to shape conceptions of normal in international relations’ constitutes its main competitive advantage (Kagan Reference Kagan2003; Manners Reference Manners2002: 239). The EU’s primary norms include peace, liberty, democracy, rule of law and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It is supposed to place these principles at the core of its relations with third countries and to help transform the domestic policies of target countries in line with them (Diez Reference Diez2005). The coherently implemented principle-based conditionality as part of enlargement, neighbourhood, trade and development policies and the material incentives it provides in return create the main mechanisms through which the EU exerts influence and legitimacy in global politics (Menon Reference Menon2014: 13).

But the EU did not fare well in terms of internal solidarity in the aftermath of the euro crisis that led to the amplifying normative paradoxes. Two main examples illustrate the case in point. The first concerns the EU’s disappointing approach to the ‘Arab Spring’. Beforehand, its stance towards Middle Eastern countries had been formed around unspoken assumptions about the national sovereignty of inherently authoritarian states (Hollis Reference Hollis2012). The EU tried to gather as much support as possible from deeply authoritarian regimes in Syria, Libya and Egypt, in terms of controlling illegal migration and countering radicalism at home. Moreover, the EU encouraged these countries to liberalize their markets and sustain bilateral trade relations (Grant Reference Grant2011: 4). In return for economic benefits and better protection against illegal migration and radicalism, the EU refrained from issuing sharp statements on the exceptionally poor democratization and human rights records there (Tocci and Cassarino Reference Tocci and Cassarino2011). These over-pragmatic EU policies were heavily criticized following the Arab uprisings. Stefan Füle (2011), then European commissioner for enlargement and European neighbourhood policy, even felt obliged to make a self-critical statement:

First, we must show humility about the past. Europe was not vocal enough in defending human rights and local democratic forces in the region. Too many of us fell prey to the assumption [that those] authoritarian regimes were a guarantee of stability in the region. This was not even Realpolitik. It was, at best, short-termism – and the kind of short-termism that makes the long term ever more difficult to build.

The EU appeared to undergo a paradigm change immediately after the Arab uprisings. The EU member states sided with popular movements against authoritarian regimes, implemented a comprehensive aid package promoting democratization and pro-democracy forces, and launched new policies (Dinçer and Kutlay Reference Dinçer and Kutlay2013: 423–4). The picture, however, dramatically changed once the Muslim Brotherhood gained a popular victory in Egypt’s first democratic elections. The rise of political Islam in Egypt, combined with the policy mistakes of the recently elected Morsi government, led to scepticism among the EU members, as a result of which the EU failed to adopt a coherent approach in confronting Sisi’s military coup in 2013. The crisis of internal solidarity among member states and, therefore, diverging policy responses in Egypt, Libya and Syria paved the wave for widespread suspicion about the EU’s intentions, capabilities and commitment to democratization beyond its own borders (Hollis Reference Hollis2012).

The second crucial test for the EU’s internal solidarity, which also seems to contribute to the illiberal turn in its periphery, relates to the 2015 refugee crisis and the EU’s relatively inept response to the unfolding humanitarian crisis. The EU for a long time remained virtually silent on the Syrian civil war and stayed on the sidelines until refugees started pouring into Europe in early 2015. Although the serious nature of the problem was henceforth recognized, the EU still failed to develop a comprehensive plan to stem the flow of migrants. Due to acute collective action problems among the member states and the EU’s inability to address the challenge at the supra-national level, member states and neighbouring countries tried to deal with the issue via unilateral policies. For instance, Hungary decided to ‘build a fence along its borders with Serbia’ (Keating Reference Keating2015); and Poland’s conservative government refused to receive any migrants as part of the EU’s refugee resettlement programme, since ‘the situation had changed [after the Paris attacks]’ (Newton Reference Newton2015).

The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, adopted a relatively liberal stance more compatible with EU norms and values, being increasingly isolated at home and in Europe (Smale Reference Smale2016). The EU’s weak internal solidarity and hazy approach in tackling the refugee crisis brings two major consequences regarding its appeal. Domestically, it created disappointment, especially among recent members. As Ivan Krastev (Reference Krastev2015) points out, ‘many Eastern Europeans feel betrayed by their hope that joining the EU would mean the beginning of prosperity and an end to crisis’. Externally, narrowly constructed interest-based refugee policies undermined the EU’s image as promoter of human rights. This, in turn, created ample opportunity for nationalist-populist leaders in the periphery to exploit the EU’s crumbling internal solidarity to further their political agenda at home.

Pull Factors

The EU’s multiple crises and inability to respond adequately to contemporary challenges are not the only mechanisms leading to substantial change in the EU’s relations with countries in the periphery. We argue that the pull factors associated with the political economy of the changing global order and the rising powers in the post-crisis equilibrium are equally important. Two main factors deserve particular emphasis here.

First, after 2008 we observed not only a disappointing performance by liberal market economies and liberal democracy, but also a spectacular rise of non-Western political economy models – the most striking being China. China’s transformation has sparked a lively discussion about the dynamics, nature and consequences of a possible move from a Western-centred to a multi-polar global order (Kupchan 2012). There exists a quasi consensus that the world has entered a post-American era, triggered by the 2008 global financial crisis. The crisis galvanized debates about alternative modes of economic governance as the pendulum of economic thinking began to swing away from the neoliberalism promoted primarily by Western countries and institutions (Williams 2014). Indeed, it accelerated the very pace of global transformations, with BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, with China as dominant actor) and near-BRICS countries (such as Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey and South Korea) consolidating their place as new centres of global economic activity. The high growth rates of emerging powers in comparison to the US’s weak recovery and the EU’s deepening crisis have accelerated the ‘West vs. the rest’ debate (The Ferguson 2011). With the ascendance of non-Western powers, rival economic governance models compete with each other; it appears that ‘strategic capitalism’ has gained the upper hand over the Anglo-Saxon and social market variants of Western-style liberal governance. Following the crisis, the rising powers have become engines of global growth in a world of sluggish European economic performance. BRICS grew 5 per cent annually, China being the locomotive with 8.6. BRICS also became new economic actors in a world economy including Europe’s periphery, through large-scale investment projects and trade opportunities. The hallmarks of strategic capitalism, however, exceed growth performance (The Economist 2012). Accordingly, the neo-mercantilist and post-Listian investment and trade policies constitute the backbone of strategic capitalist models (Strange 2014). Ian Bremmer (2010) suggests that strategic capitalism fundamentally differs from free market capitalism in two ways.

First, policymakers do not approach state intervention as a temporary phenomenon to jump-start the economy after a recession. Rather, they consider it a strategic choice to design long-term economic strategy. Second, strategic capitalists think that, rather than being an end in itself to expand individuals’ opportunities, markets are primarily ‘tools that serve national interests, or at least those of ruling elites’ (Bremmer 2010: 52). China, in particular, promotes controlled foreign direct investment (FDI) policies that encourage the transfer of technology by foreign companies and selective state intervention in production, import and export sectors. Rather than leaving resource allocation mechanisms to the market’s ‘invisible hand’, strategic capitalist models promote the state’s active involvement to regulate resource allocation, especially in high-value-added industries, as in the case of China, and geo-economically strategic sectors such as energy, as in the case of Russia.

Second, strategic capitalist models offer distinct political systems in comparison to liberal democratic European models. As Larry Diamond (Reference Diamond2015) suggests, the world is now ‘facing the recession of liberal democracy’. Accordingly, illiberal democracy practices are on the rise everywhere (Youngs Reference Youngs2015). In an era of intense anxiety and uncertainty, charismatic leadership and strong governments are perceived as the safest route to power and prosperity, while consensus-based pluralist politics is increasingly equated with the fragmentation and dilution of national power. The alleged success of the strategic capitalist models that rely on illiberal practices – promoting majoritarianism rather than pluralism through a rather narrow understanding of democracy – in the most influential rising powers create demonstration effects elsewhere, particularly for emerging middle powers aspiring to punch above their weight. In a period when democratic efficacy, self-confidence and economic dynamism recedes in Europe, the enviable growth performance of illiberal regimes turns into a source of admiration for elites who increasingly look to the East as a reference point for future economic and political development (Öniş Reference Öniş2016a). This admiration, then, influences alliance patterns and role model perceptions of various countries (Bader et al. 2010). Not surprisingly, authoritarian BRICS, such as Russia and China, emerge as the most visible role models, even for countries located within the EU’s sphere of influence (Gat Reference Gat2007; Nathan Reference Nathan2015).

The increasing investment and trade opportunities that authoritarian emerging powers provide constitute another incentive for countries in Europe’s periphery to enter into these states’ sphere of influence. Recently, authoritarian BRICS, particularly China, have become important investment and trade partners for several countries in Europe’s periphery. What makes strategic capitalism models more attractive to recipient countries is that economic incentives and credit opportunities are not tied to democratic conditionality principles advocated by the EU. As a cautionary note, drawing from ample evidence, one may suggest here that the sustainability of illiberal regimes’ economic growth performance under extractive institutions is highly dubious (Acemoğlu and Robinson Reference Acemoğlu and Robinson2012; Rodrik et al. Reference Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi2002). Yet these arguments do not seem to have an immediate practical impact in the current global context, as long as strategic models of capitalism continue to exhibit success and offer new opportunities for other rising states.

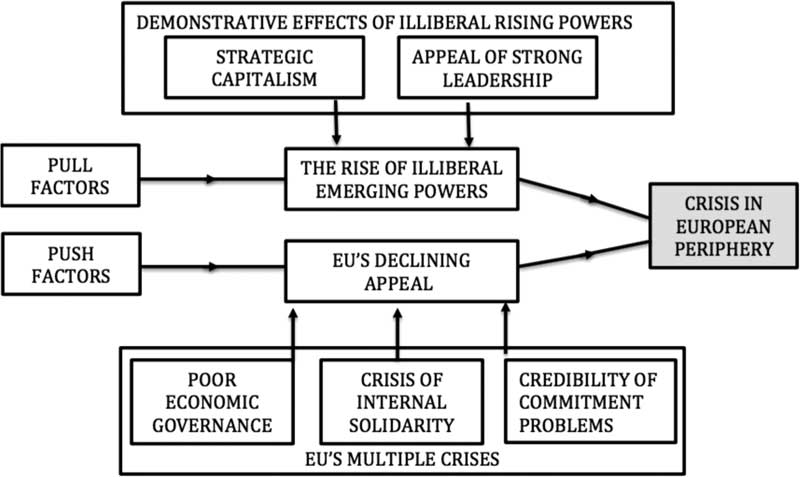

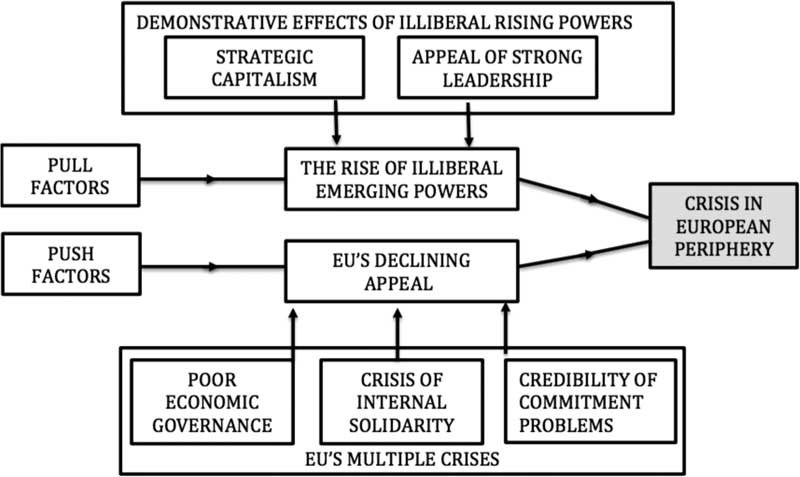

Figure 1 summarizes the push-and-pull model.

Figure 1 The Political Economy of the EU’s Declining Transformative Capacity

Crisis in the European Periphery: Hungary and Turkey in Perspective

In this section, we apply the push-and-pull framework to the Hungarian and Turkish cases as striking representatives of the EU’s declining appeal in its inner and outer periphery, respectively. Both countries experienced significant institutional transformation in the late 1990s and early 2000s, resulting in Hungary’s membership in 2004 and Turkey’s negotiating candidate status in 2005. The EU exerted massive influence and played an anchor role in these two states thanks to the material incentives it offered in return for political and economic conditionality. In comparison to other alternatives, the liberal political economy model that the EU advocated also emerged as a key norm-setter for these countries in their quest to wealth and prosperity. The reversing fortunes of Hungary and Turkey are equally striking, as both recently turned towards illiberal practices and experienced a sharp decline in reform performance. How can we explain the dramatic shift in the EU’s appeal in these member and candidate countries? What accounts for their swift de-Europeanization?

Hungary: De-Europeanization and the Illiberal Turn in a ‘Natural Insider’

The economic and political reforms that occurred in Hungary as part of the great Central and Eastern European transformation in line with liberal principles constituted one of the EU’s major achievements (Schimmelfenning and Sedelmeier Reference Schimmelfenning and Sedelmeier2005; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005). Thanks to the EU anchor, the tug of war between liberal and authoritarian/nationalist parties after the collapse of the communist regimes ended in favour of the former, as the conditional membership incentive solidified democracy and rule of law. As Andras Körösenyi (Reference Körösenyi1999: 152) points out, in Hungary a comprehensive programme was implemented ‘for limiting the state; separating the branches of power; depoliticizing the economy and the public administration; protecting individual freedoms and creating a constitutional state; as well as creating a market capitalist economy’.

The situation dramatically changed following the election of the centre-right Alliance of Young Democrats (Fidesz) under Viktor Orban. Fidesz won 52.7 per cent of the vote in the 2010 parliamentary elections, allowing the party to control two-thirds of the supermajority in parliament. Prime Minister Orban introduced a new constitution, ‘drafted by a small group within Fidesz, and no wide public discussion ensued’ (Ágh Reference Ágh2016; Kornai Reference Kornai2015: 4). European institutions criticized the constitution, and domestic opposition forces launched massive popular protests, arguing that it shrank the liberal democratic space, destroyed the checks and balance systems and curtailed fundamental rights and freedoms (Batory Reference Batory2016: 294–7). Relying on an increasingly nationalist-populist rhetoric, Orban also changed electoral law, weakened the constitutional court’s independence, jeopardized the status of competition authority, targeted the central bank’s autonomy and the private property regime, and curtailed media and academic freedoms to entrench power in his hands (Ágh Reference Ágh2016; Jenne and Mudde Reference Jenne and Mudde2012: 147–51; Kornai Reference Kornai2015). Orban succeeded in consolidating his power-base in the 2014 parliamentary elections by controlling two-thirds of the seats, despite his vote share declining to 45 per cent. Relying on his electoral success, Orban seemed to feel unrestricted in his policymaking and confident about confronting EU criticism. The consolidation of the Hungarian regime’s illiberal nature continues, while the EU’s anchor role seems to decline steadily. This sharp reversal of the EU’s impact on the Hungarian political economy can be explained using our push-and-pull framework.

First, the EU’s declining appeal in Hungary is correlated with the worsening economic conditions in Central and Eastern Europe, reflecting the collateral damage of the euro debacle’s poor management. The crisis and the way in which the EU handled it created enormous distress in Europe’s periphery, as harsh austerity measures triggered populist-nationalist sentiments. Post-communist Hungary was among the first to eliminate capital controls and privatize its economy in line with European regulations (Csaba Reference Csaba2012, Reference Csaba2013). Having made EU membership a key goal, Hungarian governments strove hard to integrate the country’s financial sector and economy with European markets. After several liberalization waves, the Hungarian economy became dependent on foreign capital flows to sustain growth. Bohle (Reference Bohle2014) calculates that 82 per cent of Hungarian bank assets were in the accounts of foreign banks headquartered in other EU states. Inevitably, the sudden halt in international capital flows following the euro crisis led to the Hungarian economy’s collapse. Confronted with a deep crisis, the incumbent socialist government had no option but to accept a loan from the IMF, the EU and the World Bank to halt the domestic currency’s slide. However, the EU and IMF’s harsh conditions did not improve the economic situation; rather, the EU-led policies further worsened the economic slump (Csaba Reference Csaba2013: 159–60). Consequently, Hungarians were deeply disappointed.

Neoliberal reforms and European integration were meant to bring unprecedented prosperity to Hungary. Yet, the euro crisis dashed these high expectations. Furthermore, it eroded the solidarity ethos within the EU, as the centre–periphery dichotomy emerged abruptly. In a post-crisis survey, the Pew Research Center found that ‘72 percent of the respondents thought that they were worse off economically than under communism’ (quoted in Batory Reference Batory2016: 291). Among Hungarians, the EU’s poor crisis management and the ‘dictates of the EU technocrats’ led to a wave of distrust and anger towards the EU institutions, which Orban’s government was quick to exploit. In one of his speeches, Orban lambasted EU interventions, declaring that Hungary ‘will not be a colony [of the EU]’ and ‘Hungarians will not live as foreigners dictate, will not give up their independence or their freedom’ (quoted in Traynor Reference Traynor2012). Orban’s government thus exploited the majoritarian understanding of democracy and expanded its popularity by questioning the EU’s ‘democratic deficit’. In a speech dismissing the European Commission’s criticism, Orban stated: ‘I was elected; the Hungarian government was also elected; as well as the European Parliament . . . But who elected the European Commission? What is its democratic legitimacy? And to whom is the European Parliament responsible? This is a very serious problem in the new European architecture’ (quoted in Jenne and Mudde Reference Jenne and Mudde2012: 149).

Second, the EU’s declining power over Hungary stems from its own crisis of internal solidarity in the eyes of the Hungarians; this provides ample opportunity for nationalist populism to dominate the domestic political space. Since collective action problems could not be overcome at the supra-national level, member states tried to develop their own solutions, which turned out to be beggar-thy-neighbour policies. Faced with a massive influx of migrants that boosted fear and anxiety, each member state tried to externalize the refugee crisis; consequently, peripheral countries felt themselves left out in the cold. This, in turn, exacerbated already rising Eurosceptic feelings and opened more space for nationalist-populist leaders. Orban (Reference Orban2015), for instance, claimed that ‘we are expecting a solution from Brussels, which will never come . . . Everything is now happening in an uncontrolled fashion.’ He also criticized EU policies for being ‘misguided’, as they ‘threaten to have explosive consequences’ (Orban Reference Orban2015).

Pull factors should also be taken into consideration to explain Hungary’s drift away from liberal European principles and norms. The increasing appeal of the rising powers in the global political economy and the emergence of illiberal regimes deserve particular attention. Orban (Reference Orban2014) stated this rather bluntly: ‘I don’t think that our EU membership precludes us from building an illiberal new state based on national foundations.’ Orban (Reference Orban2014) even claimed that ‘the era of liberal democracy is over’ and announced the formation of a parliamentary committee to monitor ‘foreigners who try to gain influence in Hungary’. He then pointed out Russia, Turkey and China as examples of ‘successful nations, none of which is liberal and some of which aren’t even democracies’. Models of strategic capitalism appear to have become a credible alternative for Hungarian decision-makers wishing to revitalize economic growth. Not only the demonstrative effects, but also the material opportunities provided by authoritarian rising states have gained practical relevance. Russia’s role is critical in this regard. Since his admission to premiership, Orban concluded lucrative economic deals with Russia’s Vladimir Putin. For instance, in 2015 Hungary signed a contract with Russia to build a €12.5 billion nuclear power plant, which attracted the EU’s criticism, but was not cancelled (Byrne and Oliver Reference Byrne and Oliver2015).

Moreover, Orban opted for unorthodox state-led policies resembling strategic capitalism, especially in the finance and banking sectors, a set of policies that BRICS countries have been implementing for some time. First, Orban made it clear that he did not want to renew the stand-by agreement with the IMF and challenged EU financial bodies to ‘protect the Hungarian national sovereignty’ (Csaba Reference Csaba2013: 159; Johnson and Barnes 2015). The Hungarian government fully repaid its debt to the IMF, which shut down its long-standing representative office in Hungary. Second, Orban’s government increased its pressure on the central bank’s independent monetary policy and criticized its governor for not cutting interest rates fast enough. Finally, in March 2013, Orban replaced the central bank’s governor with one of his close aides, who then fired multiple staffers who opposed Orban’s interventionist policies (Johnson and Barnes 2015: 548–9). Third, Orban adopted policies to increase state control over the domestic economy by reducing the strength of foreign banks in the Hungarian financial sector. To this end, he levied flat taxes directly targeting foreign banks and pursued punishment policies against them. The state-led unconventional policies of Orban’s government were a reaction to neoliberal policies along the lines of strategic capitalist models. The striking point is that Orban’s economic policies ‘did achieve many of the orthodox economic goals that previous governments have failed to attain’ (Csaba Reference Csaba2013; Johnson and Barnes 2015: 551). His unorthodox policies’ success, in turn, enhanced the legitimacy of, and Orban’s ambitions for, the Hungarian illiberal regime in the making.

Turkey: De-Europeanization and the Illiberal Turn in an ‘Important Outsider’

The evolution and dynamics of Turkey–EU relations has witnessed many ebbs and flows. The early 2000s were marked by the Europeanization of Turkey (Demirtaş Reference Demirtaş2015; Öniş Reference Öniş2008). However, the EU-factor in the Turkish political economy started to wane after a short-lived golden age, in a gradual but decisive manner (Öniş Reference Öniş2016b). The 2011 general elections turned into a watershed moment, not only for the trajectory of Turkish politics, but also for the way in which the EU is perceived in Turkey. Following the 2011 elections, the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP – Justice and Development Party) obtained half of the total vote. For the first time in Turkey, a political party had won three successive elections (2002, 2007 and 2011), with increasing vote shares. This unprecedented success consolidated Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s power as the party’s unquestioned leader. Consequently, domestic politics became characterized by the gradual erosion of institutional checks and balance mechanisms, and the country moved away from the previous reformist spirit (Özbudun Reference Özbudun2014). First, important setbacks occurred in the realms of the freedom of expression and media independence (Freedom House 2015). Second, successive reform attempts to democratize Turkey’s current constitution did not achieve their potential (Cengiz Reference Cengiz2014); on the contrary, the judiciary’s independence has been curtailed and the politicization of legal decisions jeopardizes trust in the judicial system (Öniş Reference Öniş2015). Third, in the economic realm, the political pressures on the independence of the central bank and other regulatory institutions have intensified. The state’s role in the economy became increasingly non-transparent and seems to shift away from EU standards (Acemoğlu and Üçer Reference Acemoğlu and Üçer2015). Both the number and value of non-transparent public procurements, for instance, reached almost 45 per cent (quoted in Acemoğlu and Üçer Reference Acemoğlu and Üçer2015: 15–16). All these developments demonstrate the EU’s weakened anchor role, so much so that the EU ceased to be an influential norm-setter in Turkish politics (Yılmaz Reference Yılmaz2015: 91). Again, the push-and-pull framework captures the underlying dynamics of the EU’s declining appeal.

The first push factor is closely related to the reversing fortunes of the European and Turkish economies. The membership’s anticipated economic benefits have always been a key driving factor in Turkey’s EU bid. The EU member states’ economic welfare and the Turkish economy’s poor developmental performance played a catalyst role for Turkey to adjust its economy in line with European standards. Over the past decade, the situation started to change, however. Thanks to an uninterrupted growth performance in a single-digit inflation environment, the per capita wealth of average Turkish citizens increased from $3,500 to around $10,000 in current prices; consequently, the gap between the EU average and Turkey decreased from 61 to 47 per cent in a decade. Following the global economic crisis, when the euro area grew only 0.7 per cent in 2010–14, Turkey managed to grow 5.4 per cent annually. Turkey’s high growth-performance vis-à-vis EU economies boosted the government’s confidence, so much that Erdoğan (Reference Erdoğan2012) argued that the EU no longer represented an ideal model in terms of ‘economic and political stability’. The prime minister at the time, Ahmet Davutoğlu (Reference Davutoğlu2011), also hailed Turkey’s economic success and suggested that it now posed a role model for Europe, rather than vice versa:

Turkey is no longer a country that waits on the doorstep of the EU and IMF for a couple of billion [dollars]. Turkey has turned into a country that is capable of aiding other countries and contributes to solving their economic problems thanks to the dynamism of its economy. We are not a burden to the EU; we are the cure [for European economies].

Second, the EU’s weakening role for Turkey stems from the EU’s internal solidarity crisis, which resulted in normative paradoxes and reduced credibility of commitment. In fact, worsening Turkey–EU relations pre-date Europe’s economic crisis (Müftüler-Baç Reference Müftüler-Baç2008; Öniş Reference Öniş2008). Bilateral relations plunged into a stalemate following the EU’s request that Turkey sign the Additional Protocol in 2004. The EU asked Turkey to open its ports to Greek Cypriot vessels as part of its customs union with the EU, on the grounds that Cyprus also became an EU member following the 2004 enlargement. Turkish policymakers, however, claimed in a 2005 declaration that the EU did not live up to its promises regarding the improvement of Turkish Cypriots’ status, although they had voted for a solution in the referendum with a 65 per cent approval of the Annan Plan (Müftüler-Baç Reference Müftüler-Baç2008; Yaka Reference Yaka2016: 152–3). In return, the Council of the European Union suspended negotiations on eight chapters and decided not to provisionally close others until Turkey implemented the customs union fully and in a non-discriminatory manner. Furthermore, the EU did not allow direct trade to alleviate Northern Cyprus’s isolation and adopted an indifferent approach, despite pre-referendum promises to the contrary.

Turkish rule-makers interpreted the EU’s approach as a violation of its normative credentials, as Greek Cypriots were rewarded with membership, even though they had overwhelmingly rejected the Annan Plan. Moreover, the ‘privileged partnership’ status offered by core EU countries instead of full membership and adding more criteria – such as absorption capacity – that had not been highlighted in the acquis further decreased the EU’s credibility in the eyes of Turkish policymakers and public opinion alike (Aydın-Düzgit Reference Aydın-Düzgit2006; Keyman and Aydın-Düzgit Reference Keyman and Aydın-Düzgit2013). Davutoğlu (Reference Davutoğlu2013) openly stressed this point: ‘[Turkey] does not trust the EU any more . . . [and] cannot any longer rely on the EU’s verbal promises.’

The EU’s appeal over Turkey was substantially jeopardized with the Arab uprisings and subsequent tectonic shifts in the Middle East. The EU’s inconsistent approach to the Arab upheavals (Dandashly Reference Dandashly2015) and the way in which the Turkish ruling elite perceived it was a particular turning point in this regard. The apparent contradictions of its policy choices due to the lack of internal coherence and solidarity undermined the EU’s credibility in the eyes of the Turkish ruling elite. For instance, Erdoğan (Reference Erdoğan2013) expressed his frustration in the following way: ‘The EU did not even gather its courage to call the military coup in Egypt a “coup”.’ According to Erdoğan (Reference Erdoğan2013), the EU’s appeasement policies towards the Sisi regime, combined with its inaction in the Syrian crisis, transformed it into an ineffective foreign policy actor in the Middle East. He criticized the EU for remaining ‘silent about Syria [and Egypt] in such a region where very important events are taking place’.Footnote 1

The refugee crisis constituted the last straw in the series of disappointments. Turkey has become one of the main destinations for refugees. As of late 2016 it hosts more than 3 million Syrians, for whom Ankara had spent almost $10 billion as of early 2016. Once the refugees flocked to Europe, the EU institutions and member countries’ hastily crafted policies – which, again, stemmed from its internal crisis of solidarity – attracted severe criticism of regional countries, including Turkey. Accordingly, Turkey directed two distinct criticisms against the EU. First, the Turkish government questioned the EU’s stance for its overly pragmatic approach and hesitance to allocate refugees as being in direct contradiction to Europe’s alleged values, norms and principles. Erdoğan (Reference Erdoğan2015) held European countries directly responsible for ‘the death of each refugee in the Mediterranean’, and Davutoğlu (Reference Davutoğlu2015) invited Europe ‘to look in the mirror, be honest about what it sees in the reflection, to stop procrastinating and start assuming more than its fair share of the burden’. Second, the traditional supporters of Turkey’s EU membership, mainly left- and right-wing liberals, expressed their frustration about the EU abandoning its principles for the sake of immediate Realpolitik interests (Aktar Reference Aktar2015). Europe, so the opponents maintain, is now overwhelmingly concerned with the refugee masses flowing over its borders, often from Turkish territory, and willing to shelve worries about democracy in Turkey (Aktar Reference Aktar2015). It is claimed that German Chancellor Merkel’s visit to Turkey shortly before the November 2015 election clearly strengthened Erdoğan’s position and lent him further credibility, despite the backsliding of the rule of law, fundamental rights and the freedom of media and academia (İdiz Reference İdiz2015). Strikingly, the European Commission president, Jean Claude Junker, admitted in leaked talks with Erdoğan dating to October 2015 that the commission’s annual progress report on Turkey would be held back until after the election so as not to jeopardize bilateral security cooperation (New Europe 2016). These developments prompted the perception among pro-European segments that Turkey–EU cooperation on refugees ‘is misplaced and illegitimate when it happens in disregard of the democratic values that the EU has long sought to project onto its candidates’ (Saatçioğlu Reference Saatçioğlu2016).

Not only push factors, but also the emergence of new centres of attraction and the pull dynamics they generate should be taken into consideration. In this sense, AKP leadership has been influenced by the BRICS’ more illiberal versions, for instance China with its outstanding economic performance. The ruling elite’s boosted confidence led them to pursue more assertive economic policies, blended with nationalist and centralized rhetoric. The increasing frequency of political interventions in the central bank’s functioning on the ground of protecting national interests against foreign conspirators – which Erdoğan named the ‘interest lobby’ – and the declining independence of regulatory institutions clearly illustrates this trend (Özel Reference Özel2015: 3). This turn is closely related to the substantial challenges to liberal democracy and market economy in Europe and the allure of more statist strategic capitalism models in the emerging economies. For instance, the Turkish president’s chief adviser repeatedly claimed that the ‘EU is a declining power destined to break up’ (Bulut Reference Bulut2014a) and implied the virtual abandonment of Turkey’s membership based on its growing desire to be an integral part of a shifting global order where China and Russia are expanding their spheres of influence (Bulut Reference Bulut2014b). Indeed, Erdoğan pronounced his desire for Turkey to abandon its long-standing EU aspirations and become a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (Berberoğlu Reference Berberoğlu2013; Öniş and Kutlay Reference Öniş and Kutlay2013). Increasing economic linkages with Russia turned into an important motivation behind this shift. Despite a short interval of setback in Turkey–Russia relations, their trade relations skyrocketed to more than $30 billion over the last decade, and Turkey became an important destination for Russian investors and tourists (Öniş and Yılmaz Reference Öniş and Yılmaz2016). Clearly, this marks a radical shift in Turkey’s orientation, echoing the tones of strategic capitalism blended with illiberal elements, with an emphasis on economic and political stability under the auspices of a strong leadership (Öniş Reference Öniş2016a).

A Comparative Analysis

We can identify several common elements that link the two cases. The first and most important common denominator appears to be a deep sense of disappointment with the EU. In the case of Orban’s Hungary, within the context of our model, economic factors play a critical role. Hungary has been deeply affected by the negative impact of the euro crisis. The euro crisis has also undermined the economic incentives the EU can offer to induce compliance with European norms. More recently, the handling of the refugee crisis and the lack of a coherent approach on the part of key EU elites constituted another source of disenfranchisement. Although Hungary has been an EU ‘insider’ as full member since 2004, one could also sense that Hungary does not consider itself part of the real EU ‘core’. In other words, Orban effectively capitalized on the EU’s crisis of internal solidarity that led to the sense of marginalization.

In Turkey, the ‘outsider’, the sense of disappointment is even greater and has been very strong given that, after a promising start, the negotiation process reached a stalemate. The virtual breakdown of the negotiation process and the absence of any credible commitment to Turkey’s membership has generated a deep sense of resentment and triggered strong nationalist sentiments. A promise of shallow security-based cooperation seems to have replaced the promise of deep integration, in the context of the recent refugee crisis; this lacks the potential to revitalize Turkey–EU relations so as to enhance the EU’s leverage on Turkish domestic politics and to block the growing base of illiberal practices. The fact that the Turkish economy has been doing reasonably well, at a time when much of Europe has found itself in a deep economic crisis, has also eroded the material incentives that the EU used to utilize as leverage on Turkey. Furthermore, Turkey’s economic performance vis-à-vis Europe’s economic crisis generated over-confidence in the minds of the Turkish leaders, who now believe that Turkey can accomplish its development goals without being part of a deep integration scheme. Parallel to the Hungarian case, the way in which the EU has handled the refugee crisis has also elicited widespread criticism in Turkey. The refugee issue is important in illustrating how Orban in Hungary and Erdoğan in Turkey have used this issue in very different ways to generate a nationalistic critique to build domestic popular support and claim moral superiority over the EU.

The limits of European transformative capacity in Turkey became further evident following the failure of the coup attempt in July 2016. The EU came under severe criticism from the government as well as opposition circles for its lukewarm reception of the massive popular reactions that helped to protect the civilian regime from a possible military intervention. Concerns were raised in both the US and Europe regarding the government’s response and the scale of the purges in the name of penalizing groups responsible for the attempt to overthrow the democratic regime. The concerns expressed in Europe were interpreted as attempts to interfere in Turkey’s domestic politics and an implicit endorsement of the coup, generating strong nationalist sentiments in the process. In the case of the US, these sentiments were even stronger given the US authorities’ unwillingness to extradite Fethullah Gülen, who was identified as the mastermind behind the failed coup attempt. Without a doubt, the post-coup environment in Turkey has strengthened Erdoğan’s position and restricted political space for possible criticism of democratic malpractices in the domestic political sphere.

Second, in both countries there exist powerful political parties led by dominant and charismatic leaders who were able to capitalize on the EU’s unfulfilled promises, progressively deepening as a result of the EU’s multiple crises. These political parties also have the capacity to mobilize a large majority of the population, given the extremely weak and fragmented opposition parties in both countries. The resulting unbalanced political structures have paved the way for illiberal practices in both cases, leading to the erosion of the checks and balance mechanisms necessary for a well-functioning liberal democracy. The EU’s weakening anchor role, combined with weak domestic opposition, has allowed illiberal parties to expand their power-base in Europe’s inner and outer periphery. Third, in both cases, mass parties led by strong nationalist-populist leaders increasingly look toward the East for new political economy models of development. The appeal of strategic capitalism associated with the authoritarian Russia–China axis – and Putin’s leadership style – is particularly striking. This style of capitalism promises economic benefits in an environment of significant concentration of political power in the hands of the centralized executive, in a way clearly incompatible with EU norms.

Beyond these commonalities, however, there are also noteworthy differences. The first one concerns the limits of the illiberal turn in Europe’s inner and outer periphery. There are limits to the extent to which Hungary, as insider, can deviate from EU norms. Certainly, Orban has no intention of leaving the EU and considers it crucial for Hungary’s long-term economic and security interests. In the case of outsider Turkey, however, the potential for divergence from EU norms is considerably stronger. It is a well-established fact that the EU’s transformative effect has historically been much stronger on member states or candidate countries with a credible chance of full membership. While the EU’s disciplining measures may become more difficult to implement once a country is actually an insider, the cost of exiting is nonetheless high; therefore, it is likely to exert a disciplinary effect and establish a certain boundary for actions that apply to non-compliant cases. No such mechanisms exist for countries in the outer periphery, which lack credible commitments towards full membership. The cost of non-compliance is low; hence, the likelihood of deviation from EU norms is correspondingly much higher, as is apparent in the Hungarian and Turkish cases.

The second striking difference stems from the contrasting positions adopted with respect to the ongoing refugee crisis in both countries. Hungary veered to a very strong ‘closed-door’ approach to refugees, which has been described as inhumane by the vast majority of the EU. In contrast, Turkey under the AKP has adopted an extreme version of an ‘open-door’ policy and effectively used it to build the image of a humanitarian actor, which also became a functional legitimization device in the sphere of domestic politics. Unlike Hungary, which considered the EU too lenient towards the influx of refugees, Turkey’s position was quite the reverse, as the Turkish ruling elite criticized the EU for not effectively sharing the burden and failing to admit an adequate number of refugees. Third, the economy constitutes a sphere where the two countries appear to have differed in recent years. Hungary’s economic performance has been comparatively weak, which, in turn, constituted a source of criticism against the EU, especially in the context of the euro crisis, with costly ramifications in the Hungarian case. Turkey, on the other hand, has been doing relatively better in the economic realm; this has been a factor in the argument that the EU’s incentive structure is perhaps no longer as critical as it was in the past, especially at a time when the EU itself is experiencing a major crisis that has led to a prolonged period of stagnation.

Conclusions

We highlighted the weakening of the EU’s transformative capacity in the broader European periphery in a rapidly shifting global political economy with reference to two critical cases. Although Hungary, as a member state, is an ‘insider’ and Turkey, as a candidate country, a relative ‘outsider’, their experiences in recent years display similar patterns that raise important concerns regarding the EU’s political and economic appeal as a norm-setter. Both countries, under the influence of strong nationalist-populist leaders backed by powerful majorities, have been moving in an increasingly illiberal direction, away from the well-established EU norms and principles. That being said, the aim of this article is neither to discuss the domestic sources of rising illiberal tendencies in Europe’s periphery, nor to explain the divergence in the degree of democratic regression in these countries with reference to existing literature on the ‘transformative power of Europe’. Rather, the article specifies an analytical framework based on a combination of push and pull factors, which explains the declining appeal of the EU over its periphery with reference to the changing dynamics of global political economy. It takes into account not only the internal dynamics of European integration and its multiple crises, but also the appeal of the more authoritarian versions of strategic capitalism employed by the rising powers, which increasingly serves as reference point for the elites of several states in diverse geographical settings.

The Hungarian and Turkish cases highlight certain parallels between the EU’s declining leverage in the insider as well as outsider cases. This should not lead us to overlook the fact that the EU contains the potential to exercise considerably more leverage over insiders. The ability of countries such as Hungary to deviate from EU norms by a considerable margin is constrained by the fact that the EU can use the ‘exit option’. In contrast, the EU’s incentive structure of benefits of entry and costs of exit is largely inoperative in the case of a country such as Turkey, where the membership option lacks credibility and the threat option involving the cost of exit is largely absent. The strong insider vs. outsider dichotomy in the EU is aptly illustrated by recent developments. The EU has been concerned about illiberal practices within its existing borders, particularly following their spread to a larger and economically more dynamic member state, Poland. Indeed, the European Commission has proposed action to curb illiberal constitutional politics in Poland. In the Hungarian case, there have also been some strong reactions to Orban coming from EU institutions. These criticisms particularly surfaced after Hungary adopted a rather tough approach to the ongoing refugee crisis. In contrast, similar concerns about illiberal trends in domestic politics have been much more subdued in the Turkish case, as key European elites have sought Turkey’s active cooperation in managing the refugee crisis. Given that Turkey seems to be far away from membership in the foreseeable future, concerns about its domestic political developments appear to have been largely subordinated to the single-minded concern of managing the refugee crisis at all costs, thus providing a new layer of external legitimacy to an existing hybrid regime that is of a growing illiberal nature.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

An earlier version of this paper was presented at a conference on Turkey–EU Relations at Bologna University, Bologna, May 2016. We would like to extend our special thanks to Robert Wade, Elena Baracani, Birgül Demirtaş, Şuhnaz Yılmaz, Emrah Karaoğuz, Merve Çalımlı and two anonymous reviewers of the journal for their very useful comments and suggestions.