Explaining government formations is one of the most flourishing research agendas of the last few decades. Scholars of government formations nowadays largely turn their attention to empirically testing hypotheses by combining conceptual, formal models with statistical tests (see most prominently Martin and Stevenson Reference Martin and Stevenson2001, Reference Martin and Stevenson2010). From the early 2000s the research agenda on government formations began to broaden by, first, turning its attention to the application of coalition theories to the subnational level, ranging from analysing the determinants of government formations at the regional and local level (e.g. Bäck Reference Bäck2003a; Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus, Müller and Bäck2013; Skjæveland et al. Reference Skjæveland, Serritzlew and Blom-Hansen2007), to the duration of local government formations (e.g. Blockmans et al. Reference Blockmans, Geys, Heyndels and Mahieu2016) and the termination of governments at the regional level (e.g. Martínez-Cantó and Bergmann Reference Martínez-Cantó and Bergmann2020). Second, and more recently, scholars started to switch their focus from explaining the likelihood of a government to be formed to analysing a party's likelihood of being part of, or heading, a government (Glasgow et al. Reference Glasgow, Golder and Golder2011, Reference Glasgow, Golder and Golder2012; Glasgow and Golder Reference Glasgow and Golder2015). However, these two strands of the literature have not yet been combined in one single empirical contribution. By applying existing coalition theories and theoretical expectations determining the likelihood of parties' government membership at the subnational level, this article answers the following research question: Who gets into subnational governments and what are the determinants of government membership at the subnational level?

Studies on parties' chances of entering coalition governments are almost exclusively conducted at the national level (e.g. Döring and Hellström Reference Döring and Hellström2013; Glasgow and Golder Reference Glasgow and Golder2015; Glasgow et al. Reference Glasgow, Golder and Golder2011, Reference Glasgow, Golder and Golder2012; Savage Reference Savage2014; Warwick Reference Warwick1996). Our knowledge regarding the determinants of parties' likelihood of entering coalitions at other political levels is exclusively based on insights from local politics in Sweden and Catalonia. For the Swedish case, Hanna Bäck (Reference Bäck2003a, Reference Bäck2008, Reference Bäck, Giannetti and Benoit2009) shows that a party is more likely to become a member of a coalition the more seats it controls, if it is the median party, and if the party is characterized by low levels of factionalization and intraparty democracy. One major drawback of these findings is the exclusive focus on individual party factors and their effects on a party's likelihood of entering a coalition, without taking into account that a party's probability of joining a coalition does not only depend on its own characteristics but also on the features of the potential coalitions of which the party would be a member (Glasgow and Golder Reference Glasgow and Golder2015). Studies on parties' likelihood of entering local government coalitions must account for party-level and coalition-level characteristics. In a recent study on local government formations in Catalonian municipalities, Albert Falcó-Gimeno (Reference Falcó-Gimeno2020) adopts this approach and shows that an increase in seat share of a party significantly increases the likelihood that the party will enter local government. Being the incumbent party, however, only increases the chances of re-entering government if the incumbent government coalition can re-form again. Furthermore, a party's likelihood of entering local government increases if the party is ideologically close to the median legislator in the local council.

Yet, I argue that individual parties' likelihood of entering government at the subnational level is influenced not only by classic political actors' policy-, office- and vote-seeking incentives (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999), but also by an additional institutional constraint not covered in the above-mentioned studies on local government formation in Catalonia and Sweden: the party affiliation of the directly elected head of the executive. The affiliation of this central figure should affect the likelihood that a party will enter subnational government, increasing its chances if the party is the subnational branch of the head of the executive's party or if it is ideologically close to the head of the executive's party. This argument is not restricted to the local level but can also be transferred to the regional level if regional heads of the executives are elected directly by the voters (e.g. in Greece, Indonesia, Italy, Slovakia).

Using a novel data set on local government formations in Germany (1999–2016), the empirical findings show, first, that the party of the directly elected head of the executive – that is, the mayor – has an advantage in the local coalition formation game. The party of the head of the executive is significantly more likely to become a coalition member than other parties. Second, ideological proximity to the head of the executive's party is advantageous for parties if they want to be part of a coalition. Third, other determinants of local government membership resemble the determinants of government membership at the national level – parties with a higher seat share are more likely to become coalition members as well as parties of the incumbent coalition if they can re-form this coalition. The findings highlight the emanating effects of directly electing the head of the executive on individual parties' likelihood of entering subnational government coalitions. Accounting for this additional institutional constraint provides a more nuanced picture of how party- and coalition-level characteristics affect individual parties' chances of entering subnational governments.

Party-level characteristics affecting parties' likelihood of entering subnational government coalitions

Leaving aside the possibility of securing office by obtaining an absolute parliamentary majority, a party's chances of entering government are not only determined by its own characteristics but are also dependent on the characteristics of the potential coalitions to which the party belongs (see Glasgow and Golder Reference Glasgow and Golder2015). The following theoretical expectations regarding a party's likelihood of entering subnational government coalitions primarily focus on party-level characteristics, whereas expectations regarding the effects of coalition-level characteristics on subnational government formation will be used as control variables and elaborated in the third section of this contribution.

The first expectation considers the specific incentives direct elections of heads of the executive create for subnational political actors to form government coalitions in situations where no single party gained an absolute majority. Regional presidents in Italy (see Schakel and Massetti Reference Schakel and Massetti2018; Wilson Reference Wilson2015) or local mayors in most Western and Eastern European countries play a crucial role at the respective levels of political decision-making. Regularly they are head of the subnational administration, shape the subnational policy agenda and thus have a powerful role in day-to-day governance. Regarding government formation, however, it makes a difference if a head of the executive is directly or indirectly elected. When the head of the executive is elected by local council members (as in Sweden or in Catalonia) or members of the regional parliament, and when no party gains a parliamentary majority, a government coalition forms and subsequently elects as head of the executive a politician who is a member of one of the government coalition parties. No party has a significant institutional advantage in becoming the head of the executive's party. Therefore, what matters in local coalition formation in such ‘quasi-parliamentarian’ systems are a party's seat share and its ideological position or factionalization, among other things (see Bäck Reference Bäck2003a, Reference Bäck2008, Reference Bäck, Giannetti and Benoit2009; Falcó-Gimeno Reference Falcó-Gimeno2020).

With the implementation of direct mayoral elections in many European countries, however, mayors can now be considered as ‘functional equivalents’ to popularly elected presidents in presidential, semi-presidential or ‘mixed’ systems, respectively (Bäck Reference Bäck, Haus, Heinelt and Stewart2005; Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Steyvers, Delwit, Reynaert, Reynaert, Steyvers, Delwit and Pilet2009). These institutional reforms have been accompanied not only by providing directly elected mayors with independent democratic legitimation by voters but also by a strengthening of mayors' powers vis-à-vis local councils (Borraz and John Reference Borraz and John2004; Denters Reference Denters, Bäck, Heinelt and Magnier2006; Ervik Reference Ervik2015). Even though local councils are still relevant players in day-to-day governance (Egner Reference Egner2015), local government systems are now largely ‘characterized by a dual power structure’ with the mayor on one side and the local council on the other (Denters Reference Denters, Bäck, Heinelt and Magnier2006: 271). This changes local government formation considerably. Mayors perceive their influence in local policymaking to be higher when they are backed by a local council majority (Denters Reference Denters, Bäck, Heinelt and Magnier2006), and obtaining a supporting council majority should be easier for a mayor if their party is part of that coalition. Comparable with the strategic thinking of presidents at the national level (Glasgow et al. Reference Glasgow, Golder and Golder2011: 939; Kang Reference Kang2009; Strøm et al. Reference Strøm, Budge and Laver1994), directly elected mayors want their party to be represented in local governments, and by publicly declaring their preferences for the outcome of local council coalition-formation processes, mayors can influence coalition formations in the local parliament as ‘powerful players’ (Strøm and Swindle Reference Strøm and Swindle2002). These patterns can also be observed at the regional level in Greece, Indonesia, Italy and Slovakia (see e.g. Marušiak Reference Marušiak2018; Wilson Reference Wilson2015). Consequently, being the party of the head of the executive should be advantageous in subnational government formation and this party should have a higher likelihood of getting into a government coalition than other parties:

Hypothesis 1: The party of the directly elected head of the executive is more likely to enter subnational government coalitions.

Second, day-to-day governance in politics is characterized by many formal and informal negotiations between subnational parliamentarians, members of government factions and the head of the executive. Big differences in policy views between these actors can lead to gridlock in day-to-day governance or, at least, to an increase in bargaining and transaction costs (Borraz and John Reference Borraz and John2004). As at the national level in semi-presidential and presidential systems, this is particularly the case in situations of ‘cohabitation’ (in semi-presidential or mixed democratic regimes) or ‘divided government’ (in presidential systems), respectively: that is, when a permanent majority in the legislature is opposed to the head of the executive and does not include the party of the head of the executive in the coalition (see e.g. Elgie Reference Elgie2001; Kirkland and Phillips Reference Kirkland and Phillips2018). This is a serious threat to day-to-day governance and political actors perceive this peril in advance because ‘workability … turns out to be an important concern in coalition formation’ (Warwick Reference Warwick1996: 499). Similar to the argument regarding parties' ideological proximity to formateurs at the national level (see Savage Reference Savage2014), subnational political actors should also have incentives to decrease the ideological proximity to the head of the executive in order to increase the workability of a coalition and to minimize intra-coalitional conflict. Even if the party of the head of the executive is not part of the coalition, small ideological differences between a coalition party and the head of the executive could prevent high bargaining and transaction costs. Studies on government formation in presidential systems corroborate this expectation by showing that parties are more likely to become a coalition member if they are ideologically close to the president because this gives ‘the government coalition more leeway in policymaking’ (Alemán and Tsebelis Reference Alemán and Tsebelis2011: 7).Footnote 1 Hence, I hypothesize that ideological proximity to the head of the executive's party should be advantageous for political actors when forming subnational government coalitions:

Hypothesis 2: Parties that are ideologically close to the party of the head of the executive are more likely to enter subnational government coalitions.

Third, the advantage of being the party of the head of the executive in the subnational government formation game might be reinforced by the fact that parties need to be of a considerable size to be able to win elections determining the head of the executive. For example, small political groups will either not have financial resources to run a candidate for head of the executive elections, or they decide to support candidates of larger parties, at least in the runoff elections between the two candidates who received the most votes. Hence, only large parties have a realistic chance to win these direct elections. The head of the executive, thus, will be a member of a large or even of the largest party in the legislature (see e.g. Steyvers et al. Reference Steyvers2008). But even if a large party is not holding the position of the head of the executive, this party will still have considerable bargaining power in coalition formation processes because a party with a large number of seats inevitably will be part of a larger number of potential coalitions than a smaller party, depending on the legislative party system (Laver and Benoit Reference Laver and Benoit2015). Therefore, I hypothesize that the size of a party affects a party's likelihood of entering a coalition (Glasgow et al. Reference Glasgow, Golder and Golder2011; Isaksson Reference Isaksson2005; Savage Reference Savage2014; Warwick Reference Warwick1996):

Hypothesis 3: The larger a party's seat share, the higher the party's likelihood of entering subnational government coalitions.

Fourth, subnational political actors not only strive to hold important offices, they also seek to implement their preferred policy positions in day-to-day policymaking. Therefore, subnational parties' policy positions should matter for their likelihood of joining a government coalition. As shown for the Catalonian and Swedish case on local government formations, parties controlling the median legislator or that are closer to the median position have a higher chance of joining a coalition (Bäck Reference Bäck2003b, Reference Bäck2008, Reference Bäck, Giannetti and Benoit2009; Falcó-Gimeno Reference Falcó-Gimeno2020). This is corroborated by findings for national government formations where ‘[h]olding the median ideological position should help a party enter government’ (Glasgow and Golder Reference Glasgow and Golder2015: 745), and being ideologically close to the median legislator should be advantageous for parties wanting to become coalition members (Döring and Hellström Reference Döring and Hellström2013):

Hypothesis 4: The smaller a party's distance to the median legislator's ideological position, the higher the party's likelihood of entering subnational government coalitions.

Lastly, government experience might be advantageous for parties in the subnational government formation game but only if the previous coalition did not break up due to intra-coalitional conflicts. If a party demonstrated being a constructive and reliable coalition partner, its likelihood of joining the next government coalition should be higher. In contrast, recent research from the national (Glasgow and Golder Reference Glasgow and Golder2015) and local levels (Falcó-Gimeno Reference Falcó-Gimeno2020) suggests that incumbent parties are significantly disadvantaged in negotiations to become coalition members if they are not able to re-form the incumbent coalition, which is highly unlikely if the previous government has been terminated early due to intra-coalitional conflict. Note, however, that this seems to be only valid when regarding the same set of parties in a government coalition, where parties that are responsible for early government termination due to intra-coalitional conflicts are only punished by their previous coalition partners but not by other parties (see Tavits Reference Tavits2008). Notwithstanding these conflicting arguments, I hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 5: Incumbent parties have a higher likelihood of entering subnational government coalitions.

Case selection, data and methods

The five hypotheses regarding the determinants of individual parties' likelihood to enter subnational government coalitions will be tested by studying 92 coalition formations in 34 cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants in the German states of Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia between 1999 and 2016 (see Table A1 in the Online Appendix). A coalition is defined as any cooperation between at least two political groups where political actors signed a written coalition agreement following a local election.Footnote 2

This case selection has several advantages. Using German local elections allows a direct comparison of the results for individual parties' likelihood of entering coalitions with the findings presented for ‘quasi-parliamentarian’ systems in Sweden (Bäck Reference Bäck2003b, Reference Bäck2008, Reference Bäck, Giannetti and Benoit2009) and Catalonia (Falcó-Gimeno Reference Falcó-Gimeno2020) but leverages the fact that the German local institutional setting resembles a ‘mixed’ political system that is neither purely presidential nor purely parliamentarian (Bäck Reference Bäck, Haus, Heinelt and Stewart2005; Debus and Gross Reference Debus and Gross2016; Egner Reference Egner2015; Gross and Debus Reference Gross and Debus2018a). Direct mayoral elections provide an opportunity to include an additional party characteristic and institutional constraint (Strøm et al. Reference Strøm, Budge and Laver1994) in the local coalition formation game – the party of the directly elected mayor (i.e. the head of the executive) – and individual parties' ideological distance from the head of the executive. Direct elections of mayors were introduced in North Rhine-Westphalia in 1999 and in Hesse in 1992, respectively.Footnote 3

Additionally, local councils in Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia have considerable rights both in shaping the local policy agenda and in allocating important portfolios (see Egner Reference Egner2015). The functions of a ‘local government’ are performed by the mayor and several other executive officers on an executive board, which resembles a ‘cabinet’, called an ‘administrative board’ in North Rhine-Westphalia and ‘magistrate’ in larger municipalities in Hesse (Egner Reference Egner2015: 184). These executive officers are elected and deselected by the local council. This means: (1) that mayors need to cooperate with local council majorities if they want to work together with politically aligned executive officers; (2) that mayors in Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia are not as powerful as in other German states; and (3) that local councillors consider the executive board's influence in local politics as similar to the mayor's influence (Egner Reference Egner2015: 187). The considerable amount of power for local councils in both states regarding the competencies delegated to the administration and the mayor, in combination with the high politicization of local politics, very frequently divides local councils into majority and opposition groups. This creates strong incentives for local political actors to form permanent legislative coalitions and to become part of a coalition. It is quite common for newly established coalitions in local councils in Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia to first deselect some members of the executive branch who belong to parties that are not part of the permanent legislative coalition, and then to install their own party members in these offices.

Furthermore, as the number of inhabitants increases, local politics gets more and more politicized by parties (whereas independent local lists play only a minor role) and local councils in large cities are considered as equivalents to national and regional parliaments (Egner Reference Egner2015; Gross and Jankowski Reference Gross and Jankowski2020; Reiser and Holtmann Reference Reiser and Holtmann2008). More than 40% of all cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants in Germany are in Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia (see Table A1 in the Online Appendix). The cases under study cover 43.7% of the German population living in such cities in 2019.

To sum up, using local government formations in Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia might be considered a ‘most likely case design’ for determining the factors impacting a party's likelihood of becoming a coalition member because both local government settings can be considered ‘prototypes’ of competitive political systems (Holtkamp Reference Holtkamp2008). Yet, in the conclusion I will discuss the potential of transferring the empirical insights to both local and regional politics in other German states and other countries, respectively.

Following the approach of Garrett Glasgow and Sona Golder (Reference Glasgow and Golder2015), I assume that the likelihood of a party becoming a coalition member depends not only on party characteristics, but also on the likelihood of potential coalitions of which the party is a member. Consequently, the empirical analysis takes the potential government formation opportunities into account. I apply conditional logit (CL) regression models to analyse the likelihood of a party becoming a coalition member. Each coalition formation is represented by a ‘choice set’, comprising the coalition that actually formed (coded 1 in the dependent variable choice) as well as all other arithmetically possible combinations of political groups in the local council (coded 0). Since this study deals with the determinants of local coalition membership, all potential single-party governments are excluded from the analysis. The binary independent variables indicate whether a party- or coalition-level characteristic is present (score of 1) or absent (score of 0) for the potential coalition while the size- and policy-related independent variables indicate the amount of the respective variables for the potential coalition.

Two dummy variables indicate whether the mayor's party is part of a potential coalition (mayor's party) and whether a party was part of the previous local government (incumbent party).Footnote 4 In situations where a single party had an absolute majority in the previous local council this variable is coded as 1 for this party only and 0 for all other parties. Assessing the hypothesis that parties with higher seat shares have a higher likelihood of entering local government, one has to consider how a party's seat share affects the characteristics of the potential coalitions of which the party is a member (Glasgow and Golder Reference Glasgow and Golder2015). A party's seat share should be more decisive for forming a coalition if adding this party to a coalition changes the coalition characteristic from a minority to a majority coalition. However, if a potential coalition already has a majority status, adding an additional party (regardless of the size of the party) turns this coalition to a surplus majority coalition and, thus, should decrease the formation likelihood of this coalition (see Martin and Stevenson Reference Martin and Stevenson2001). Hence, the effect of party size is captured as a curvilinear relationship by including both the size of a coalition (seat share coalition) and the squared value of this variable (seat share coalition squared). Since the mayor's party is also the largest party in 70 out of 92 cases – and to avoid problems of multicollinearity – using a party's seat share instead of a variable indicating the largest party is also a way to control for the effect of party size on individual parties' likelihood to enter local governments (see Bäck Reference Bäck2003b).

The ideological proximity of a party to the mayor's party (distance to the mayor's party) is assessed by using local parties' policy positions that are derived from the policy content of local election manifestos by applying the ‘wordscores’ procedure (see Laver et al. Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003). State parties' manifestos for several state elections in Hesse (1991–2009) and in North Rhine-Westphalia (1990–2010) have been retrieved from the Political Documents Archive (Benoit et al. Reference Benoit, Bräuninger and Debus2009; Gross and Debus Reference Gross and Debus2018b) and used as ‘reference texts’. In line with previous research on subnational party positions in Germany, the respective ‘reference scores’ to the ‘reference texts’ are state parties' policy positions on a general left–right dimension (see Bräuninger et al. Reference Bräuninger, Debus, Müller and Stecker2020; Gross and Debus Reference Gross and Debus2018a). Local election manifestos have been retrieved from the Local Manifesto Project (Gross and Jankowski Reference Gross and Jankowski2020).Footnote 5 Distance to the mayor's party is measured by using the mean ideological distance between the coalition members and the mayor's party. If a party adopts an ideological position further away from the mayor's party, the ideological distance to the mayor's party of all coalitions of which this party is a member increases. Hence, parties that are ideologically distant from the mayor's party should be less likely to become coalition members.Footnote 6 Furthermore, a party's ideological distance to the general left–right median is measured by using the mean ideological distance between the coalition members and the left–right median (distance to median).Footnote 7

I control for three main effects of coalition-level characteristics which have been found to play a decisive role in government formation processes (Bäck Reference Bäck2003a; Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus, Müller and Bäck2013; Debus and Gross Reference Debus and Gross2016; Olislagers and Steyvers Reference Olislagers and Steyvers2015; Skjæveland et al. Reference Skjæveland, Serritzlew and Blom-Hansen2007): coalitions are more likely to be formed: (1) if they are minimal winning (minimal winning coalition); (2) if potential coalitions include the smallest number of parties (number of parties in coalition); and (3) if a potential coalition is the incumbent coalition (incumbent coalition). These coalition-level characteristics are captured by using both a continuous independent variable on the number of parties in a coalition and two dummy variables indicating if potential coalitions are minimal winning and if a potential coalition is the same as the previous coalition in the local council.Footnote 8

Empirical analysis

The descriptive information already lends tentative support for the hypotheses that both being the party of the head of the executive and being ideologically close to the party of the head of the executive increase parties' chances of entering subnational government coalitions (see Table A2 in the Online Appendix). The party of the directly elected mayor has been a coalition member in 81 out of 92 cases. The mean ideological distance between coalition members and the mayor's party is unequivocally smaller for the coalitions that actually formed than compared to all potential coalitions.

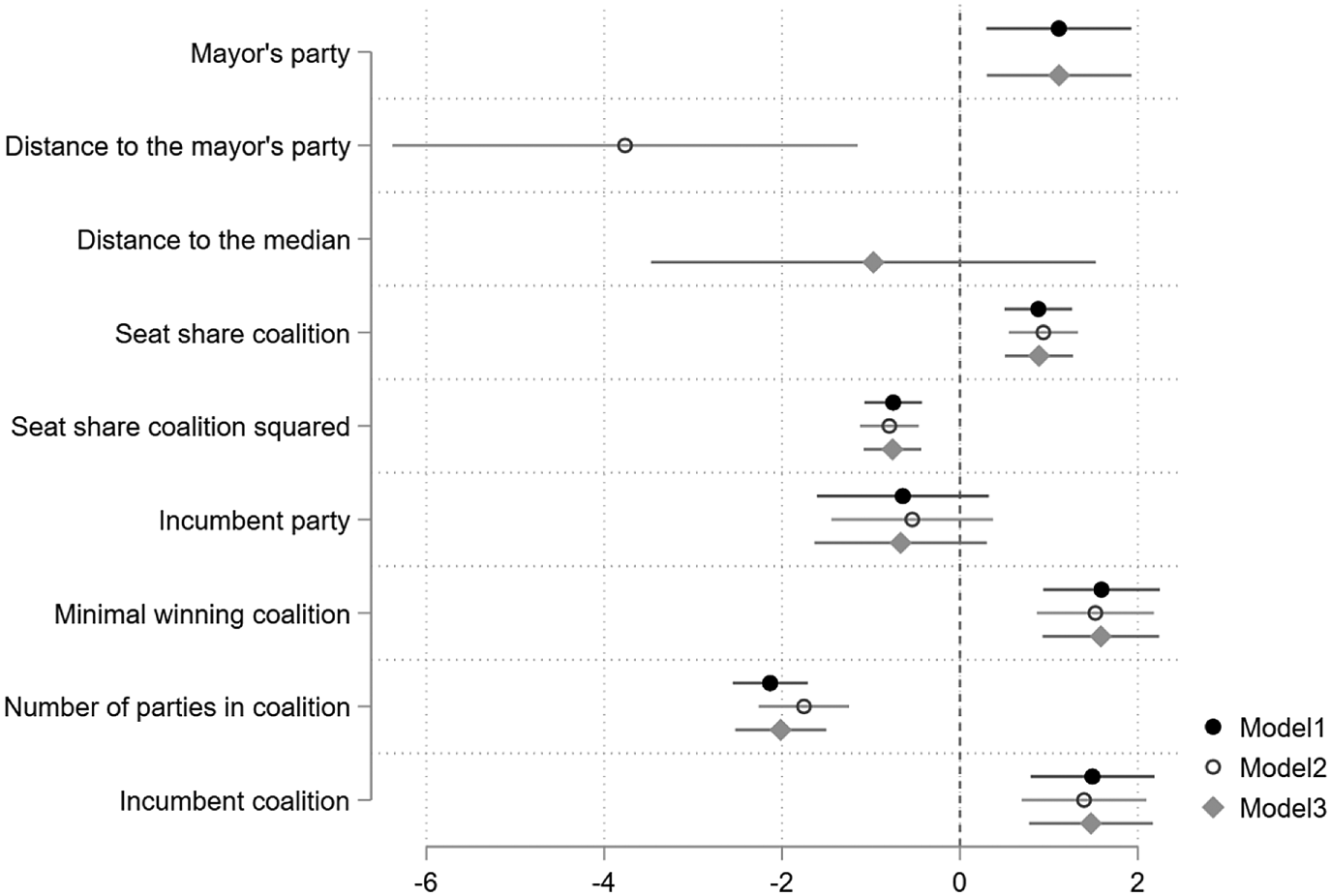

Three CL regression models have been estimated to assess the determinants of local government membership in Hessian and North Rhine-Westphalian cities (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix for the estimated results of the three models). The first model specifically addresses the hypothesis that the party of the directly elected mayor should have an advantage in becoming part of a coalition. The second model tests whether parties that are ideologically close to the mayor's party are more likely to enter local government.Footnote 9 The third model uses the mean ideological distance between coalition members to the left–right median instead of the ideologically proximity to the mayor's party to test the fourth hypothesis.Footnote 10

The coefficient estimates plotted in Figure 1 show that potential coalitions including the party of the directly elected mayor are significantly more likely than other coalitions.Footnote 11 In terms of individual parties, the mayor's party (i.e. the party of the head of the executive) is significantly more likely to become a coalition member than other parties. This is in line with the theoretical expectation formulated in the first hypothesis.

Figure 1. Determinants of Individual Parties' Local Government Membership

Note: Coefficient estimates from Models 1–3 in Table A3 in the Online Appendix (95% confidence intervals shown).

Second, party size matters. Parties with more seats in the local council have a greater probability of becoming a coalition member, thus supporting the third hypothesis and corroborating empirical findings from the subnational and national levels in different countries (see Bäck Reference Bäck2003b; Döring and Hellström Reference Döring and Hellström2013; Isaksson Reference Isaksson2005; Mattila and Raunio Reference Mattila and Raunio2004; Savage Reference Savage2014). Echoing the results in Glasgow and Golder (Reference Glasgow and Golder2015) and Mattila and Raunio (Reference Mattila and Raunio2004), however, the effect of a party's seat share is weaker the more seats a party obtains.

Third, potential coalitions are significantly less likely to form if their mean ideological distance to the mayor's party increases, thus supporting the second hypothesis. If a party adopts an ideological position further away from the mayor's party, the distance from the mayor's party increases for all potential coalitions of which this party would be a member. Consequently, the further away a party ideologically positions itself from the mayor's party, the less likely it is that this party will join a coalition. Both findings are in line with empirical findings on the likelihood of a president's party entering government and that parties which are ideologically close to the president's or prime minister's party are more likely to become coalition members (cf. Alemán and Tsebelis Reference Alemán and Tsebelis2011; Mattila and Raunio Reference Mattila and Raunio2004; Savage Reference Savage2014).

Model 3 takes into account the possibility that parties are minimizing the ideological distance to the median legislator rather than the ideological distance to the mayor's party. The results show, however, that parties that are closer to the ideological median of the local council are not more likely to become part of a coalition (and the fourth hypothesis must be rejected). Hence, it is parties' ideological proximity to the party of the head of the executive that matters in subnational government formation and not their ideological closeness to the left–right median legislator.

Regarding the coalition-level characteristics and the incumbency factor, the findings lend further evidence to recent findings in national and subnational government formation research (cf. Debus and Gross Reference Debus and Gross2016; Falcó-Gimeno Reference Falcó-Gimeno2020; Glasgow and Golder Reference Glasgow and Golder2015; Gross and Debus Reference Gross and Debus2018a; Olislagers and Steyvers Reference Olislagers and Steyvers2015): minimal winning coalitions are more likely to be formed, whereas coalitions are the less likely, the more parties they comprise. Furthermore, incumbent parties have a lesser chance of re-entering government if they are not able to renew their cooperation, because it is the incumbent coalition that has a positive and statistically significant probability of being formed again. If the members of the previous coalition are not able to renew their cooperation, then these parties are less likely to join a coalition.

Two additional specifications of the CL regression models are conducted to test the robustness of the results (see Tables A4 and A5 in the Online Appendix). First, one could argue that some parties have such extreme policy positions that they are excluded from the government formation game by all other parties. Potential coalitions comprising ‘anti-system’ parties (see Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018) thus should be extremely unlikely to be formed (Stefuriuc Reference Stefuriuc2013: 69). Since ‘anti-system’ parties are not part of any of the 92 coalitions that formed, the first robustness check uses a reduced sample of all potential coalitions excluding the ones covering ‘anti-system’ parties. The empirical findings are robust against this alternative specification. Second, local parties might additionally strive for the formation of governments that are congruent – that is, have an identical party combination – to the regional government to use information advantages, to decrease bargaining costs and to avoid sending ‘mixed signals’ to voters, who might become unsettled if their preferred party joins a coalition with Party A at the regional level but with Party B at the local level. The results show that potential coalitions are significantly more likely to be formed if they are congruent to the regional government, thus corroborating findings for local government formations in Flemish municipalities (see Olislagers and Steyvers Reference Olislagers and Steyvers2015). The substantial findings are robust against this specification with one exception: the variable incumbent party now displays a negative and statistically significant effect because controlling for the congruence between local and regional governments reinforces the effect that if incumbent parties are not able to re-form the previous coalition, they have a higher likelihood of being excluded from coalition formations than other parties.

Lastly, is there an explanation for those instances where the head of the executive's party is not part of the legislative coalition supporting the government (‘cohabitation’)? The descriptive information provided in Table 1 shows that mayors' parties had lost seats in 10 out of 11 cases. These seat losses might suggest two reasons why parties of directly elected mayors have not been included in local council coalitions.Footnote 12 First, the fact of losing seats as the mayor's party might be used by rival parties to claim that an electoral ‘loser’ does not deserve to be part of a coalition, or that voters punished the mayor's party on purpose to strengthen local ‘checks and balances’. Second, since local political actors prefer to form minimal winning coalitions, and since mayor parties are usually large parties, seat losses by mayoral parties could render preferred coalition options of the mayor's party arithmetically impossible. This offers rival parties an opportunity to exclude the mayor's party from government by allowing previously unlikely potential coalitions to be formed.Footnote 13

Table 1. Cases of ‘Cohabitation’ in Hessian and North Rhine-Westphalian Cities with at Least 100,000 Inhabitants, 1999–2016

Note: ‘Cohabitation’ describes a situation where the mayor's party is not part of the coalition in the local council. CDU = Christian Democratic Union of Germany; SPD = Social Democratic Party of Germany.

Conclusion

The empirical literature on government formations and individual parties' likelihood of joining a government has grown significantly in the last two decades. Comprehensive studies on the determinants of individual parties' likelihood of entering subnational governments, however, are largely missing, with the exception of studies on Catalonian (Falcó-Gimeno Reference Falcó-Gimeno2020) and Swedish municipalities (Bäck Reference Bäck2003b, Reference Bäck2008, Reference Bäck, Giannetti and Benoit2009), two ‘quasi-parliamentarian’ systems. Therefore, I argued that one important institutional constraint at the regional level (e.g. in Greece, Indonesia, Italy and Slovakia) and the local level (most European local government systems) has been overlooked so far: the party affiliation of the directly elected head of the executive and its effect on individual parties' likelihood of entering local government coalitions in such ‘quasi-semi-presidential’ or ‘mixed’ regimes. By using data from 92 local government coalition formations in German municipalities in the states of Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia (1999–2016), I show that the party of the directly elected head of the executive is significantly more likely to join a government coalition. Furthermore, parties that are ideologically close to the party of the head of the executive are also more likely to enter local government coalitions.

To what extent can these theoretical and empirical insights be generalized? Although local coalition formations in large cities in Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia are ‘most likely cases’, the empirical results could be transferred to local government formations in other German states. For example, it is now quite common to negotiate formal coalitions not only in larger cities but also in smaller municipalities because local party systems become more fragmented, the times of absolute majorities held by a single party are mostly over, and six out of ten councillors in German municipalities (almost nine out of ten in municipalities with at least 10,000 inhabitants) have a party affiliation (Egner Reference Egner2015: 184). Even in a local government setting like Bavaria, which is characterized by a very dominant role for the directly elected mayor and a more ‘consensual’ style of local politics (Holtkamp Reference Holtkamp2008), parties frequently form coalitions in local councils and try to include the party of the directly elected mayor (Pollex et al. Reference Pollex, Block, Gross, Nyhuis and Velimsky2021). This is also the case for coalition formations in larger cities in almost all other German states (Gross Reference Gross2018).

Nevertheless, even though German local councillors in smaller municipalities are also overwhelmingly capable of differentiating between majority and minority groups and in determining who is part of a formal or informal coalition in local councils (see Egner Reference Egner2015), a comparative analysis of local government formations in particular – and the importance of ideology in local politics in general – in municipalities with fewer than 100,000 inhabitants is more than needed. Although recent research indicates that the emergence of the Alternative for Germany is a particular threat to the electoral success of non-partisan local lists in smaller municipalities (Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski, Juen and Tepe2020), thus raising doubts about the widely held claim that ‘personalities matter more than parties’, we currently lack comparable data on factors influencing voters' decision-making in local elections.

The theoretical argument that being the head of the executive's party and being ideologically close to this party is beneficial for a party's likelihood of becoming a coalition member needs to be tested in other contexts, though. For example, since many local councillors have a party affiliation in many Western and Eastern European democracies – particularly in larger municipalities (Razin Reference Razin, Egner, Sweeting and Klok2013) – and since direct mayoral elections have been introduced in a large number of countries, the theoretical arguments and empirical findings presented here could be studied in other settings. Studies on local politics in Bulgaria (Nikolova Reference Nikolova, Loughlin, Hendriks and Lidström2011), Poland (Swianiewicz Reference Swianiewicz, Loughlin, Hendriks and Lidström2011) and Slovakia (Capková Reference Capková, Loughlin, Hendriks and Lidström2011) indicate that the relationship between directly elected mayors and local council majorities becomes tense when the party of the mayor is not part of the local council majority. Following the argument of the present study, this should create incentives for local councillors to include the party of the head of the executive in local government coalitions. Furthermore, this argument is not restricted to the local level but could also be transferred to the regional level and tested within the empirical framework applied there if citizens directly elect their regional heads of the executive (e.g. in Greece, Indonesia, Italy, Slovakia).

Much further research, however, is required. For example, the empirical findings indicate the need to gain a better understanding of the relationship between the head of the executive and her party (see e.g. McDonnell and Mazzoleni Reference McDonnell and Mazzoleni2014). One important assumption made in the literature on government formations is that the head of the executive adopts the same policy position as her party (see Alemán and Tsebelis Reference Alemán and Tsebelis2011; Martínez-Gallardo Reference Martínez-Gallardo2014). Yet, although this might be a plausible assumption if a head of the executive has been running for election on the ticket of one single party, there are numerous cases where she is supported by several parties. Whether she adopts the policy position of her own party or a position that is a compromise between all the positions of the supporting parties still is uncharted territory. Filling this research gap might allow scholars to get a more nuanced picture of government formations in (semi-)presidential systems. Furthermore, in smaller municipalities – but also in some larger cities in Germany – candidates without a party affiliation are winning direct mayoral elections. To what extent these candidates are supported by political parties and if that shapes their policy preferences is still a research question that awaits a scholarly answer.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.41.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article have been presented at the 5th Annual General Conference of the European Political Science Association 2015, and an internal seminar at the University of Oldenburg, 2017. I want to thank Anna Adendorf, Marc Debus, Michael Jankowski, Markus Tepe and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and helpful feedback. Further, I thank Anna Adendorf, Yannik Buhl, Hatice Kücük, Samuel Müller, Torben Schütz, Kenneth Stiller and Lea Maria Straßheim for assisting in the preparation of the local election manifestos.