The European Union (EU) has been in various crises for more than ten years now. One of the most pressing questions is to what extent solidarity actions can ease crisis situations and, moreover, who supports whom to overcome these challenges (Ferrera Reference Ferrera2014; Sangiovanni Reference Sangiovanni2013). Previous research has demonstrated that this question is not trivial in political or academic terms: it is politically relevant, because the lack of solidarity in past crises has thrown into doubt the future of the European integration project and the stability of democratic societies (Jones and Matthijs Reference Jones and Matthijs2017; Lahusen and Grasso Reference Lahusen and Grasso2018). It is also academically crucial, because conceptualizing and measuring solidarity and who is asked to show solidarity with whom is strongly debated in the literature (Baute et al. Reference Baute, Abts and Meuleman2019; Kneuer et al. Reference Kneuer2022). While scholars have extensively studied preferences regarding solidarity in different European countries and across a range of crises (Bechtel et al. Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Gerhards et al. Reference Gerhards2020; Katsanidou et al. Reference Katsanidou, Reinl and Eder2022; Lahusen and Grasso Reference Lahusen and Grasso2018), two questions still remain to be addressed.

First, while previous studies have investigated how the political orientation of citizens relates to their support or rejection of solidarity (Kiess and Trenz Reference Kiess and Trenz2019), the analysis of party positions has so far received scant attention. If political parties are considered, more attention has been paid to this issue in studies examining parliamentary and public debates or party manifestos (Closa and Maatsch Reference Closa and Maatsch2014; Thijssen and Verheyen Reference Thijssen and Verheyen2022; Wallaschek Reference Wallaschek2020a). Second, Alessandro Pellegata and Francesco Visconti (Reference Pellegata and Visconti2022) highlighted that future research on European solidarity should consider various types of solidarity in the same research design to compare and explain differences in conceptualization.

Against this background, we examine the estimated party positions of German political parties on different types of EU solidarity and ask to what extent these party positions relate to the sociocultural GAL–TAN – namely green/alternative/libertarian versus traditional/authoritarian/nationalist – cleavage (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). We use an original party expert survey that was collected in the run-up to the 2021 German federal elections. We designed various items on EU solidarity and crisis situations that were included in the survey alongside more general items on party positions (Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski2021). For this purpose, we conceptualize two types of solidarity: redistributive solidarity and risk-sharing solidarity. The former focuses on redistributing resources and sharing these with others (even at the expense of oneself to some extent) (Bechtel et al. Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014). The latter, in contrast, is defined as the attempt to share and reduce uncertainty by acting collectively and establishing institutional settings to prevent harm and to minimize risks for every member of a group (in this case, member states of the EU) (Schelkle Reference Schelkle2017).

Germany is often perceived as a ‘reluctant hegemon’ (Bulmer and Paterson Reference Bulmer and Paterson2013) in the EU, meaning that if the German government hesitates to support any kind of solidarity-related policy, such a policy has hardly any chance of succeeding at the intergovernmental level. Therefore, a crucial question is to what extent party positions are similar or different in the German case regarding (the two types of) EU solidarity.

We make three contributions to the literature. First, by systematically studying estimated party positions on different types of EU solidarity, we demonstrate that the cultural GAL–TAN cleavage shapes the political space on solidarity in Germany. Second, we show that support for the two types of solidarity does not vary strongly among political parties, but differentiating between long-term and short-term solidarity institutionalization produces varying levels of support. Third, and considering the timing of the analysed data, we highlight positional differences between the current German government coalition partners the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and Greens on the one side and the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) on the other. Our findings indicate a strong political tension towards EU social policies and deeper European integration in general.

Literature review

Notions of solidarity

Solidarity can be considered as a contested concept because there are many debates on how it can be characterized and differentiated from other related ideas such as charity or altruism (Bayertz Reference Bayertz and Bayertz1999). The main conceptual divide for the empirical investigation of solidarity is whether solidarity is understood as a feeling of belonging that creates a sense of community or whether solidarity is a material condition that refers to specific types of redistribution and reallocation of resources (Ferrera Reference Ferrera2014; Scholz Reference Scholz2008). Based on this broad theoretical debate, an increasing number of studies try to conceptualize solidarity empirically and test its competing notions in the context of the EU (Genschel et al. Reference Genschel2021; Gerhards et al. Reference Gerhards2020; Lahusen Reference Lahusen2020; Reinl Reference Reinl2022; Wallaschek Reference Wallaschek2020b).

Previous empirical studies on solidarity in the EU context either focus on citizens' preferences towards risk-sharing across countries in times of crisis or examine the formation of collective identities as a basis for feelings of solidarity (Baute et al. Reference Baute, Abts and Meuleman2019; Bechtel et al. Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Gerhards et al. Reference Gerhards2020; Lahusen and Grasso Reference Lahusen and Grasso2018; Nicoli et al. Reference Nicoli, Kuhn and Burgoon2020). Interestingly, both approaches show relatively high support for cross-national solidarity, but also highlight that contextual conditions are crucial. They demonstrate that vulnerable groups such as refugees or disabled people are treated differently, thus citizens are more likely to show solidarity with disabled people than with refugees (Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Lahusen and Grasso2018; Trenz and Grasso Reference Trenz, Grasso, Lahusen and Grasso2018). Moreover, to what extent a country is affected by a crisis and whether this is perceived as self-inflicted or due to external shocks shapes the solidarity response. The type of crisis influences the perception of whether cross-national solidarity is based on material conditionality, moral obligations or self-identification with the crisis-hit country (Bechtel et al. Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Biermann et al. Reference Biermann2019; Bremer et al. Reference Bremer, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2020; Cicchi et al. Reference Cicchi2020; Katsanidou and Reinl Reference Katsanidou and Reinl2022; Nicoli et al. Reference Nicoli, Kuhn and Burgoon2020). While it is obviously true that a comparison of national and European solidarity demonstrates higher support for the former (Gerhards et al. Reference Gerhards2020; Lahusen and Grasso Reference Lahusen and Grasso2018), the question of whether EU solidarity even exists or not is no longer asked. Instead, the much more interesting research question is to what extent and which type of EU solidarity is supported in the member states.

Before going deeper into diverse types of solidarity, we discuss the literature on changing party competition in Europe and how this might affect parties' more general stance towards EU-wide solidarity policies.

Party competition and EU solidarity

Party competition in Europe has already received much attention in political science research. Whereas in the beginning one axis was predominantly used to describe party competition – the economic left–right axis (see for an overview Adams Reference Adams2012) – increasing doubts arose as to whether the left–right dimension adequately captured the cleavage structure of contemporary Western societies. As a result, a second axis highlighting the sociocultural dimension of party competition has been introduced in the literature. This second axis includes attitudes towards immigration and/or the EU (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008). Liesbet Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002) and Gary Marks et al. (Reference Marks2006) famously suggested a sociocultural fault line – cutting across the left–right dimension – that structures party competition on European policy issues in EU democracies, which they then called the GAL–TAN dimension.

Political parties situated closer to the GAL pole are more likely to support European integration, while political parties closer to the TAN pole tend more towards rejecting (further) EU integration (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Marks et al. Reference Marks2006). This correlation is particularly evident for eastern European countries (Brigevich et al. Reference Brigevich, Smith and Bakker2017). Moreover, scholars demonstrated convincingly that EU issues shape party politics (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Hutter and Kerscher2016) as well as voter preferences (de Vries Reference de Vries2007; Hobolt and Rodon Reference Hobolt and Rodon2020).

Research in the field of EU issue competition rarely investigates specific policy areas when it comes to European integration. Exceptions to this are studies on the so-called Spitzenkandidaten process in EU election manifestos (Braun and Popa Reference Braun and Popa2018), parties' diverse perspectives on the EU as filtered by the media (Helbling et al. Reference Helbling, Hoeglinger and Wüest2010) and studies on EU-related issues that parties refer to in their press releases (Senninger and Wagner Reference Senninger and Wagner2015). What is missing in the literature on party positions so far, however, is an aspect of European integration that has gained relevance especially in view of the past decade and EU-wide crises: European solidarity.

Only a few studies so far have shed light on party positions regarding the social orientation of the EU and EU crisis aid. These refer to polling data from political elites or party debates without covering the overall perceptions of parties or classifying their political positioning. For example, studies by Ann-Kathrin Reinl and Heiko Giebler (Reference Reinl and Giebler2021) and Linda Basile et al. (Reference Basile, Borri, Verzichelli, Cotta and Isernia2021) examine individual politicians' stances on EU solidarity through elite surveys while others focus on parliamentary and public debates (Closa and Maatsch Reference Closa and Maatsch2014; Hobbach Reference Hobbach2021; Wallaschek Reference Wallaschek2020a). Based on these previous studies, we aim to substantiate the previous claims and formulate more specific expectations about overall party trends.

Just as GAL parties usually advocate for more EU integration and a globalized future, they are also expected to do the same regarding EU solidarity. This supposition has already been supported more specifically to financial aid in the event of an economic crisis (Reinl and Giebler Reference Reinl and Giebler2021) and we assume that it also applies to other forms of European solidarity. Based on this, we formulate our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The closer a party is located to the GAL pole, the more strongly it supports EU solidarity.

Parties that differ from all others regarding EU solidarity are Eurosceptic and/or extreme right-wing parties. These two TAN party types tend to overlap quite often (Halikiopoulou et al. Reference Halikiopoulou, Nanou and Vasilopoulou2012; van Elsas et al. Reference van Elsas, Hakhverdian and van der Brug2016). With regard to the Eurosceptic argument, we assume that if parties reject the EU and EU integration in general, they do so for each and every kind of EU policy (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Popa and Schmitt2019). With regard to the extreme right-wing parties, these often portray EU integration as eroding national sovereignty and take a more negative and critical position towards the EU compared to other parties (Dolezal and Hellström Reference Dolezal, Hellström, Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). We therefore expect that:

Hypothesis 2: The closer a party is located to the TAN pole, the more strongly it rejects EU solidarity.

All these assumptions relate to more general party positions on EU solidarity. However, research in the field of individual-level solidarity preferences within nation states as well as in the context of the EU has shown that one can distinguish between two overarching types of solidarity: risk-sharing and redistribution. In the next section we discuss parties' positioning on both these types of solidarity.

Two types of EU solidarity

Steinar Stjernø (Reference Stjernø2009: 2) defines solidarity as ‘the preparedness to share resources with others by personal contribution to those in struggle or in need and through taxation and redistribution organized by the state’. The focus on sharing resources and redistribution in the nation state led scholars to call the welfare state an ‘institutionalised solidarity’ mechanism (Gelissen Reference Gelissen2000). Our work links this literature on national welfare states (Roller Reference Roller, Borre and Scarbrough1998; Vandenbroucke Reference Vandenbroucke2020) with studies on EU solidarity.

We distinguish between two types of solidarity policies (see also Reinl Reference Reinl2022; Vandenbroucke Reference Vandenbroucke2020): redistributive solidarity and risk-sharing solidarity. While redistribution usually refers to a long-term financial reallocation aiming at equalizing (or ‘levelling up’) living conditions, risk-sharing refers to mutual responsibility in the case of damage. Redistributive policies thus aim to broadly equalize people's economic living conditions over time. An example of a domestic redistribution policy is financial redistribution between regions within a country. This kind of solidarity policy may lose its raison d’être over time, if living conditions have converged. Risk-sharing, on the other hand, comes into force whenever unforeseen events involving loss occur. This could be unemployment or a natural disaster affecting a particular region. In other words, a kind of insurance scheme is created that always kicks in when damage strikes, so risk-sharing never loses its topicality.

‘Classical’ studies on party politics and the welfare state have argued that redistributive policies and tackling social inequalities are mainly supported by left-wing parties (in government) while such state interventions, by contrast, are not welcomed by liberal and conservative parties (Allan and Scruggs Reference Allan and Scruggs2004; Boix Reference Boix1998; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley2003), especially if they imply more permanent financial costs in the future. Moreover, right-wing parties have been perceived as rather inconsistent, even blurry (Rovny Reference Rovny2013), in their redistributive policies, but scholars note that this has recently changed and radical right parties are now more explicit about their preferred welfare state policies (Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi and Michel2014).

Furthermore and following the literature on political cueing, we expect that if parties support redistributive policies on the national level, they may also support these policies on the EU level (Anderson Reference Anderson1998; de Vries Reference de Vries2018). If parties favour state regulation of the market and redistribution through taxation to combat social inequalities, they may also support EU-wide redistributive policies as a further step towards deeper political European integration. In contrast, if parties oppose redistributive policies on the national level, they are expected also to oppose such policies on the EU level. These parties may be generally more sceptical towards state interventions in the market, regardless of the political level of competence. This is in line with previous research by Zsófia Ignácz (Reference Ignácz2021) operating at the citizen level. The author shows not only that individuals do hold similar preferences for redistribution policies for various political levels but also that the underlying considerations are comparable across spheres.

We therefore expect to find stronger preferences for EU redistributive policies among left-wing and green parties while all other parties presumably reject such a long-term commitment. In contrast to that, we expect that risk-sharing policies at the EU level are less contested among political parties because such policies focus rather on specific crisis moments and are (often) short-term commitments with supposedly immediate effects. EU risk-sharing may be understood as necessary mean to prevent the EU from falling apart or to avoid more substantive consequences for European integration in the long run. With the aim of stabilizing the community permanently, joint crisis assistance could be in the interests of all pro-European parties. Eurosceptic parties, on the contrary, which reject ‘their’ country's EU membership altogether, would have no interest in the survival and safeguarding of the community (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Popa and Schmitt2019). Since hardly any German political party is completely against the EU, apart from the Alternative for Germany (AfD), or wants to leave the integration project (Hutter et al. Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016), we expect to find fewer differences among the political parties towards risk-sharing solidarity:

Hypothesis 3: The positional difference between GAL and TAN parties should be more pronounced for redistribution than for risk-sharing policies.

The widening of this gap is expected to be even more intensified once a policy is accompanied by long-term institutionalization (Gerhards et al. Reference Gerhards2020; Lengfeld and Kley Reference Lengfeld and Kley2021). If EU solidarity of any kind is not restricted to a certain situation or period, its rejection by TAN parties could grow. This is because long-term policies permanently affect the national sovereignty and monetary competences of the EU member states. Any transfer of power and political authority to EU institutions would be rejected by TAN parties. This leads us to our fourth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: The closer a party is located to the TAN pole, the more it rejects institutionalized solidarity policies of all kinds.

This article addresses these current gaps in party research and examines party political positions towards EU solidarity as well as the nuances governing their stances.

Data and methods

Case selection

Germany is an interesting case study for support of EU solidarity because it has often been considered one of the best examples of the ‘permissive consensus’ (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009) around EU issues. However, with the founding of the AfD in 2013, the political space broadened during the euro crisis and Eurosceptic sentiments even grew against the backdrop of the 2015 migration crisis (Bremer and Schulte-Cloos Reference Bremer, Schulte-Cloos, Hutter and Kriesi2019). Moreover, the radical left party (Left Party, Die Linke) opposes the EU in terms of market integration and austerity policies but supports EU integration with regard to social issues and EU solidarity in particular (Pellegata and Visconti Reference Pellegata and Visconti2022; Reinl and Giebler Reference Reinl and Giebler2021). Thus, support or rejection of EU solidarity is crucial for understanding the political contestation of European issues in the German party system and how different types of solidarity may reflect the ‘conflictual dissensus’ on European integration (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009).

Along with France, Germany is one of the driving forces of European integration and is often perceived as a reluctant leader in times of crisis (Crespy and Schmidt Reference Crespy and Schmidt2014). Germany was the largest creditor state during the euro crisis, contributing the largest share of all EU countries to the crisis funds, and it took in the most refugees in 2015–2016. Although during the years of the euro crisis Germany and a large part of its population opposed common European debts and advocated austerity measures, this reserved reaction to European solidarity policies changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. With the decision to launch the NextGeneration EU Fund, the EU's policy towards crises changed considerably and this directional shift was supported by the German government (Howarth and Schild Reference Howarth and Schild2021).

Thus, studying party positions on various items of EU solidarity in the run-up to the German federal elections of 2021 may show whether the recent turn towards more EU integration is further substantiated among German political parties.

The open expert survey 2021

A team of German political scientists initiated a party expert survey in the run-up to the 2021 German federal elections (Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski2021). A total of 361 political scientists took part in the survey, which created a sufficiently large sample for the analysis of party positions. The data is publicly available via the Harvard dataverse and is free to download. It draws on an earlier expert study by Kenneth Benoit and Michael Laver (Reference Benoit and Laver2006) and includes a large number of already established survey items, but scholars also had the chance to incorporate specific sets of questions. Topics covered in the survey range from migration, economy, gender, minority rights and social issues to EU specific questions (see also Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski2022).Footnote 1

Regarding the latter topic area, a question on the general shift of competences to the EU level was included. Following this, five questions dealt in detail with EU solidarity: expenditure at the EU level, the reduction of economic inequality within the EU, the introduction of an EU-wide social system, assistance in times of crisis within the community, and an EU-wide common debt.Footnote 2 If necessary, variables were recoded so that higher values represent more support for EU-level solutions.

Experts were asked to position eight political parties on the respective survey items, namely: the Left Party, Alliance 90/Greens, SPD, FDP, Free Voters (FW), Christian Democratic Union (CDU), Christian Social Union (CSU) and the AfD. We excluded the FW from our analyses because the FW does not usually run in all German election districts and the party is not currently represented in the Bundestag. Moreover, the party experts also had difficulties positioning the FW in the selected questions and experts answered questions for the FW less often than for the other parties.Footnote 3

The advantage of using this expert data over alternative sources is that not only do we get a general classification of the parties on EU solidarity, but positions are reflected in a very nuanced way. The topic of EU solidarity is captured in great detail with its various dimensions. Moreover, expert data do not refer to judgements of single-country coders, as is often the case for manifesto projects, but allow for an average to be determined over consulted experts in the field. Previous research has shown that expert studies provide reliable information both compared to other data sources and with reference to EU integration (Steenbergen and Marks Reference Steenbergen and Marks2007, for a recent overview see also Meijers and Wiesehomeier Reference Meijers, Wiesehomeier, Carter, Keith, Sindre and Vasilopoulou2023).

However, the disadvantages of this type of data should not be concealed (Laver Reference Laver2014). On the one hand, respondents may simply lack knowledge about some parties, especially if the party is newer or its positioning is less prominent (as in our case of the FW). On the other hand, respondents' own assessment of the parties could strongly influence their ranking on the dimensions and thus skew them in a certain direction (Curini Reference Curini2010). Given the fact that no other data source so far provides such a detailed picture of party positions on EU solidarity, the advantages of choosing this data over alternative sources outweigh the disadvantages.

Our statistical analyses proceed in three subsequent steps: (1) we look at the item of EU competences to identify the general positioning of political parties towards transfers of political authority for the EU. In the next step, (2) we look at the median dataset of the party expert survey. We analyse this data instead of mean data, as it is more resistant to outliers. We test whether the second dimension of party competition – the GAL–TAN dimension – explains the positioning of political parties towards EU solidarity in Germany. As discussed above, this scale is suitable for our purpose as it explicitly captures the transnational aspect of political conflict. For this purpose, we sum up the following items in the party expert survey: position on immigration, liberalism, climate change and feminism. In the last step, (3) we zoom in on two types of solidarity to further investigate party positioning and discuss differences between the parties. The next section presents our empirical analysis and discusses the results.

Results

Party positions towards EU competences

Before we turn to the assigned party positions on EU solidarity, we take a step back and consider parties' preferences for an expansion of competences at the EU level. If an expansion of such competences at the EU level is rejected, it is highly likely that any kind of EU solidarity policy will be rejected too.

Figure 1 illustrates the average party positions assigned by the experts. In cases where the confidence intervals of the parties overlap (the ‘fences’), we do not find significant differences between them. What we find is that on average, the Greens are evaluated as the party that would like to see more competences going to the EU. Somewhat lower, but still significantly different compared to the others, is the SPD position, whereas we find no differences between the positions of the CDU, CSU, FDP and the Left Party. The lowest average values were attributed to the AfD, which is significantly different from all the other parties. Thus, while we find clear support for more EU competences among the Greens and SPD, the centre-right parties CDU, CSU and FDP as well as the radical Left Party are relatively indifferent to increasing the competence level of the EU. The right-wing populist party AfD is against the expansion of competences in the EU.

Figure 1. Preferences for EU Competences, by Political Party

Source: Raw expert positions (Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski2021); authors' own calculation.

Positioning EU solidarity on the GAL–TAN axis

We now turn to the second step of our analysis by looking at the GAL–TAN dimension and the EU solidarity index regarding the positioning of the German political parties. The five items on EU solidarity mentioned – expenditure at the EU level, the reduction of economic inequality within the EU, the introduction of an EU-wide social system, assistance in times of crisis within the community and an EU-wide common debt – are summed up in an EU solidarity index (with the same weight for all items) to investigate the nature of the relationship between EU solidarity and the GAL–TAN dimension.Footnote 4

Figure 2 shows that the seven parties are sorted into two quadrants: the Greens, the Left Party and the SPD are in the pro-EU solidarity GAL quadrant while the FDP, CDU, CSU and AfD are positioned in the anti-EU solidarity TAN quadrant. The Greens and the AfD lie at opposing ends of a linear relation, because these two parties are the most (Greens) and least (AfD) solidarity-minded parties and they are also the parties closest to the GAL and TAN poles. Thus, our first and second hypotheses are supported because those parties that are closer to the GAL pole are also more in favour of EU solidarity (H1). Conversely, parties that are closer to the TAN pole are less in favour of EU solidarity (H2).

Figure 2. Positioning on EU Solidarity and the GAL–TAN Dimension of German Political Parties

Source: Median data (Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski2021); authors' own calculation.

Party stances on EU solidarity: redistribution and risk-sharing

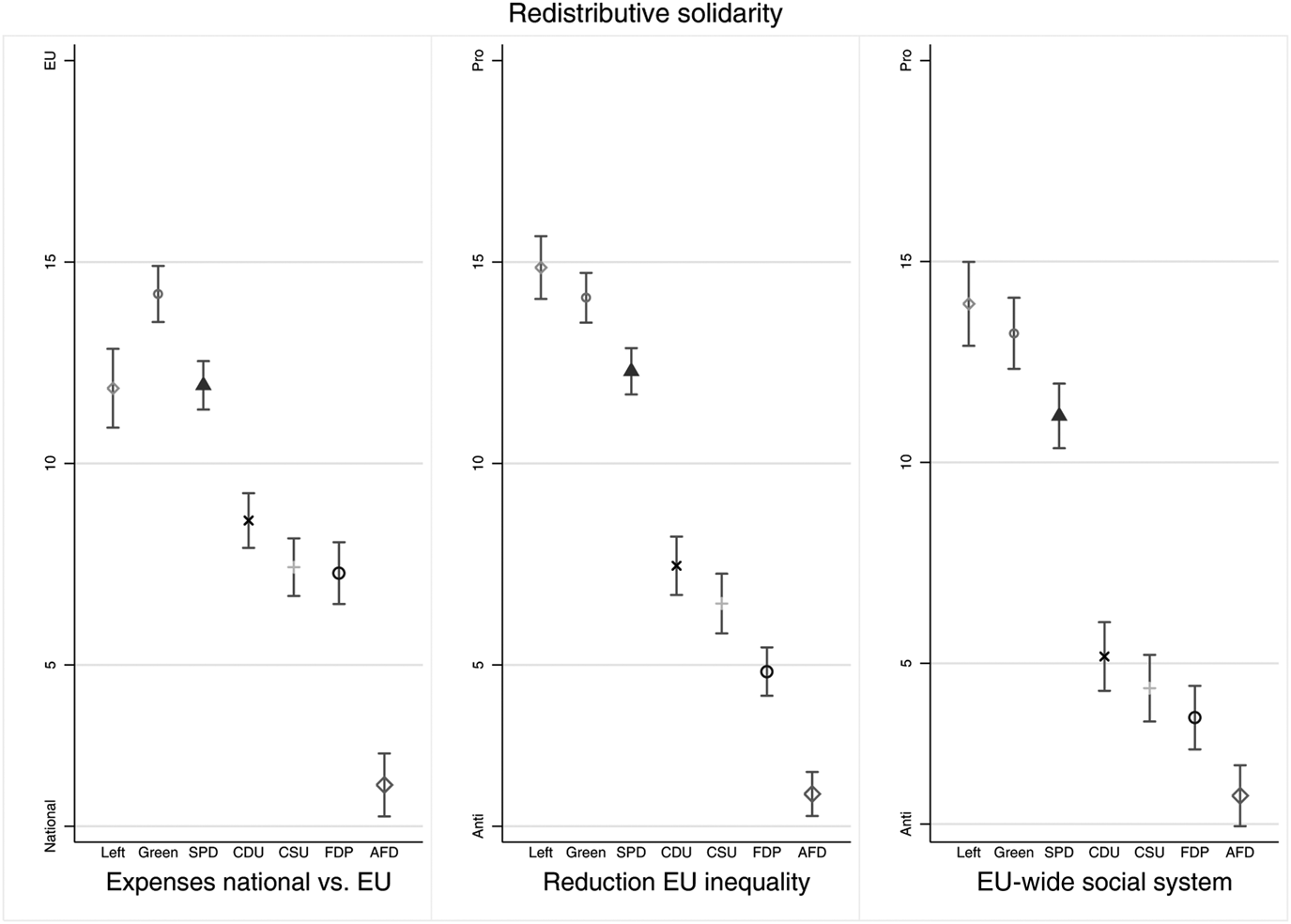

Based on the previous findings, the question arises as to whether this difference between GAL and TAN parties is generally transferable to different types of EU solidarity. We therefore test our third and fourth hypotheses by delving deeper into the positioning of political parties on EU solidarity policies. We categorize the five EU solidarity items used according to the two types of solidarity introduced. Dedicating expenditures to the EU level, the reduction of economic inequality within the EU and the introduction of an EU-wide social system are viewed as redistributive solidarity, while assistance in times of crisis within the community and an EU-wide common debt scheme are instances of risk-sharing solidarity. This two-dimensional structure is also supported by a factor analysis run over all political parties. Figure 3 presents the results on redistributive solidarity for each of the political parties.

Figure 3. Positioning on Redistributive Solidarity of German Political Parties

Source: Raw expert positions (Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski2021); authors' own calculations.

The results in Figure 3 show a positional divide between the GAL parties (Left, Greens, SPD) and the TAN parties (CDU, CSU, FDP, AfD) for all three items. Redistributive solidarity is strongly supported by the GAL parties while the TAN parties rather reject redistributive solidarity in the EU. While the right-wing party AfD is clearly positioned as an anti-EU solidarity party on all these items, the level of scepticism from the CDU, CSU and FDP varies with the level of institutionalization. Redistributing resources without a mechanism governing how exactly this should be done across the EU seems to be more accepted among the three parties than the idea of an EU-wide social system that may have stronger implications for the German welfare state as well as presenting a risk of long-term financial liabilities. This observation is in line with H4, that the more institutionalized the policies, the greater the resistance to them by the TAN parties.

Among the GAL parties, it is noticeable that the SPD and Greens show almost no change in position on the three items, while the Left Party is most supportive of reducing economic inequalities in the EU. The distribution of resources in favour of all European countries is viewed with the most scepticism (although it is still supported) of the three items.

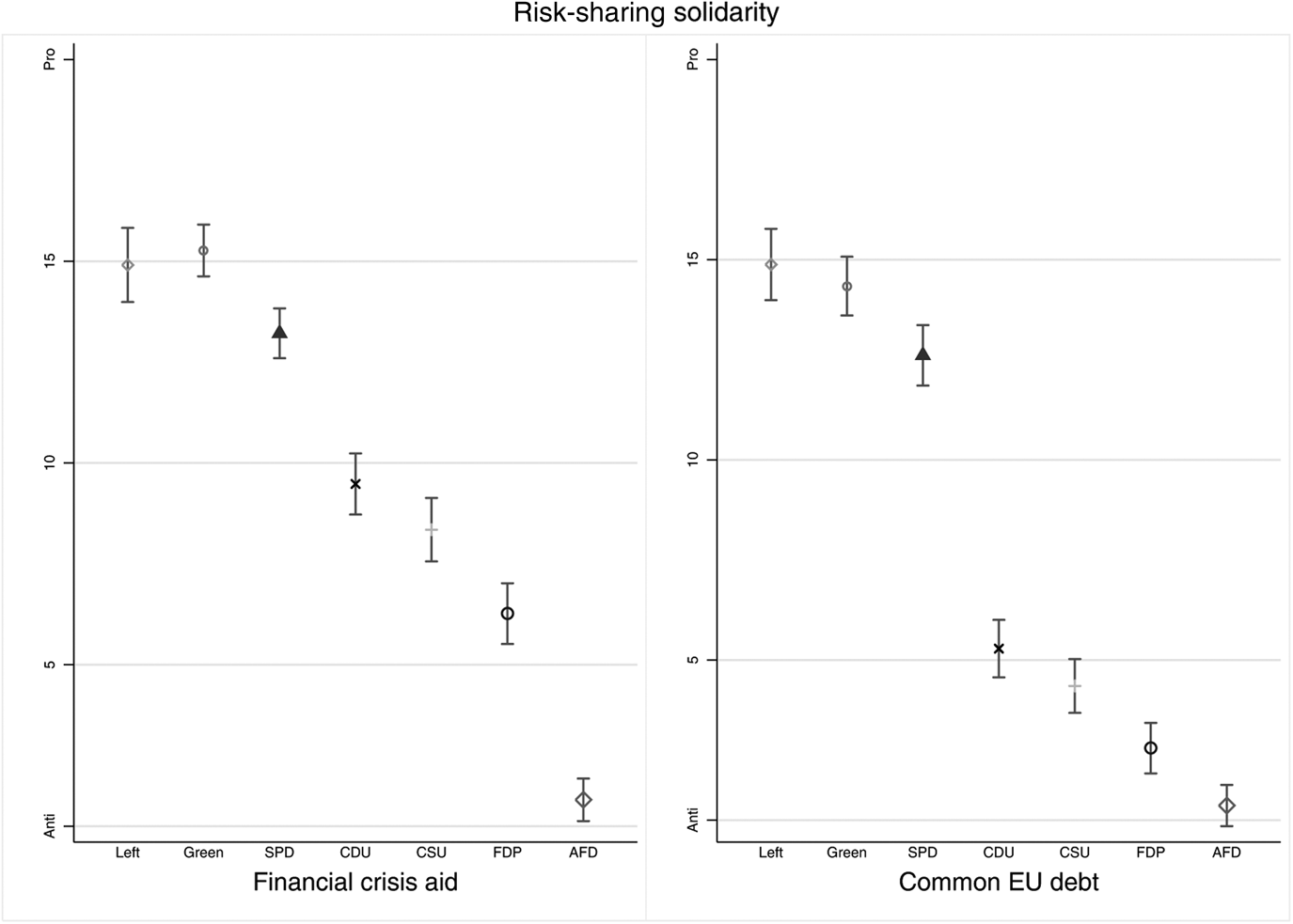

Figure 4 presents the results for risk-sharing solidarity for all seven political parties. This second type of solidarity is measured by means of the items on financial assistance in times of crisis within the communityFootnote 5 and on the EU-wide common debt scheme. As above, the GAL parties strongly support both forms of risk-sharing solidarity, financial crisis aid even more than an EU common debt scheme. In contrast, TAN parties are more sceptical of risk-sharing solidarity, particularly regarding the common debt scheme in the EU. Again, the AfD is positioned on the opposite side and firmly rejects risk-sharing solidarity. Among the other TAN parties (CDU, CSU and FDP), risk-sharing with regard to direct financial aid for crisis countries is taken into account by the CDU and CSU and less by the FDP. However, in the case of establishing a common debt for EU member states, risk-sharing in financial terms is rejected (represented in the extreme by the AfD).

Figure 4. Positioning on Risk-sharing Solidarity of German Political Parties

Source: Raw expert positions (Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski2021); authors' own calculations.

Again, the coherence in the ascribed positions among GAL parties is noticeable and represents a strong positioning for risk-sharing solidarity. Nevertheless, there are (small) significant differences between the SPD on the one hand and the Left Party and Greens on the other.

If we now compare these two endorsements of redistribution and risk-sharing, we find only partial evidence to back our third and fourth hypotheses: we see that the divide between the GAL and TAN party camps tends to appear quite similar for both types of solidarity (implying a rejection of H3), but that a greater institutionalization of solidarity generally entails a stronger rejection by TAN parties (which supports H4).

Discussion and conclusion

This article investigated the positioning of German political parties on two types of EU solidarity by using an original party expert survey from 2021. Three main conclusions can be drawn from our results.

First, party positioning on EU solidarity is structured by the GAL–TAN cleavage in Germany. The Greens, SPD and Left Party are identified as GAL parties while the CDU, CSU, FDP and AfD are positioned more closely to the TAN pole. These differences between GAL and TAN parties are pronounced and there are significant differences between these party groups. In particular, the AfD occupies the TAN pole while the Greens are the most explicitly positioned GAL party. Our findings thus support previous studies that argue that there is a structuring effect of the GAL–TAN cleavage for the political space in European countries (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002) and the opposite positioning of the AfD and Greens in Germany (Franz et al. Reference Franz, Fratzscher and Kritikos2019). Furthermore, while extreme right and left parties are usually classified as Eurosceptic (Hobolt and de Vries Reference Hobolt and de Vries2016), our findings suggest a more differentiated picture. The finding that the AfD opposes any kind of EU solidarity confirms previous studies that voters for radical right parties oppose European solidarity (Kiess and Trenz Reference Kiess and Trenz2019; Pellegata and Visconti Reference Pellegata and Visconti2022). The pronounced pro-EU solidarity positioning of the Left Party, however, shows that radical left parties may oppose market integration but strongly support the social dimension of the EU – so-called ‘social Europe’. Thus, our analysis supports recent accounts that argue for a more fine-grained analysis of the critical positions of radical left and left populist parties towards the EU (Bortun Reference Bortun2022; Pellegata and Visconti Reference Pellegata and Visconti2022).

Second, there are hardly any differences in the positioning of the parties towards the two investigated types of solidarity – redistributive and risk-sharing – in the EU. The GAL parties unanimously support both types of solidarity while the TAN parties reject redistributive solidarity in the EU. We find, however, that the institutionalization of EU solidarity is strongly contested between GAL and TAN parties. Whether it is about a common debt scheme for EU member states or the introduction of an EU-wide social system, both items are strongly supported by GAL parties (Greens, Left Party, SPD) and strongly opposed by TAN parties (CDU, CSU, FDP, AfD).

Third, the traffic-light coalition established in Germany in 2021 (SPD, FDP, Greens) may face lasting internal conflicts on the future of the social dimension in the EU (see also Reinl and Wallaschek Reference Reinl and Wallaschek2022). The smaller coalition partners, the FDP and Greens, are quite distant from each other on every analysed item, underlining rather hesitant position-taking by the FDP and more pro-integrationist approach by the Greens, leaving the SPD in the middle in our study. This uncovered discrepancy could be relevant in relation to the future expansion of Europe's social dimension, which has recently received more attention in the wake of the pandemic. At the same time, the current energy crisis resulting from the war in Ukraine brings EU-level policies back into the spotlight. Once again, it is a matter of pulling together at the EU level, keeping in mind not only energy supply and economic policy, but also social consequences in the EU member states. Hence, looking at solidarity in the EU has strong political and societal implications that should be further investigated.

Our study focused on a rather favourable context (Germany) for investigating EU solidarity, because of Germany's powerful position in the EU (politically and economically) as well as the high resonance of solidarity in the German public debate. This also means that being at the receiving end of solidarity is relatively inconceivable for the German population and could also be a reason why debt mutualization receives the strongest opposition among all TAN parties. Nonetheless, such a party constellation in which a green party and a right-wing populist party are the two ends of the political continuum is common in many European countries (e.g. Sweden, Austria, the Netherlands) and our results demonstrate not only a GAL–TAN cleavage, but that there is also a distinct political divide over EU solidarity. Our findings from the German case might therefore be a first hint at how EU solidarity may spur political conflict in other EU member states.

Our study has two main limitations. First, we analysed types of institutionalized solidarity, disregarding notions of solidarity that focus on identity and community-building. However, in party expert data, investigating these mentioned notions might be rather difficult and hard to assess by party experts because the party positions and policies behind identity-based solidarity may be somewhat fuzzy.

Second, data availability is another limitation. It would be interesting to investigate how political parties in other countries position themselves on EU solidarity. Moreover, our cross-sectional data allows neither for the mapping of developments over time (before and after certain crises) nor for drawing causal inferences. In the future, therefore, longitudinal expert data on EU countries would be necessary in order to examine the object of study even more closely. Nonetheless, our results and the developed survey items can be used for future comparative studies and should be considered for large comparative datasets on party positions such as the Manifesto Project (MARPOR) or the Chapel Hill Expert Survey.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2023.1.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers as well as Christian Stecker, Jan Philipp Thomeczek and Peter Thijssen for valuable feedback and comments on previous versions of our manuscript. An earlier version of this article was presented at the ECPR General Conference in Innsbruck 2022. We also thank Peter-Peer Felix Wagner for excellent research assistance. Our work on the paper was financially supported by the LMU Mentoring Program.