Social media summary

Adaptation to climate change needs regional action. Collaborative initiatives help regions promote and track progress.

1. Introduction

A well-known challenge of addressing climate change is the fact that it is a global issue, yet its impacts are felt on a regional and local scale. Consequently, efforts to promote resilience to the impacts of climate change need to involve regional and local governments (Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Weinfurter and Xu2017). The development of adaptation policies and action in particular has traditionally been framed as a local problem, falling largely under the responsibility of regional governments and local communities (Climate Chance & Comité 21, 2019, p. 33). However, in recent years, and particularly since the 2015 Paris Agreement established a global goal on adaptation, adaptation has risen on the global policy agenda (Persson, Reference Persson2019). At the same time, scholars have begun to observe that the framing of adaptation as a local problem is insufficient. As Nalau et al. (Reference Nalau, Preston and Maloney2015) have argued, while adaptation is practiced at the local level, it does not necessarily follow that it is best governed at the local level.

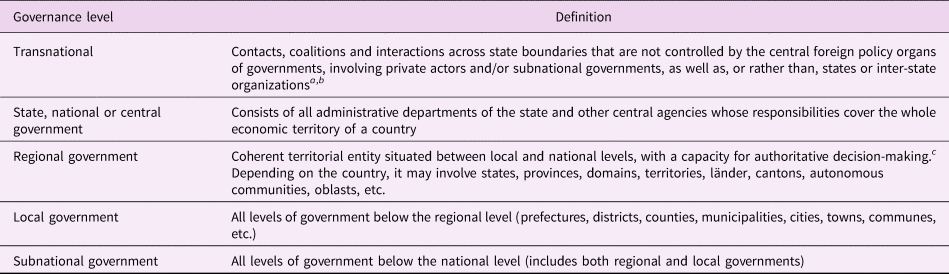

In addition to the climate goals that they commit to and the action that they take on the ground, regional and local governments steer behaviour towards shared goals by engaging with other actors transnationally (see Table 1 for definitions of the terms used to describe governance levels). This relationship is defined as an instance of ‘transnational climate governance’ (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012). Transnational climate initiatives are expected to meet three criteria: explicitly address climate change; operate transnationally (i.e., incorporating parties from at least two countries and one non-state actor); and seek to foster and steer action towards a specific goal (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012). The engagement of subnational governments in transnational climate action has proliferated over the past two decades (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Brandi and Bauer2016; Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011; Roger et al., Reference Roger, Hale and Andonova2017; van der Ven et al., Reference van der Ven, Bernstein and Hoffmann2016).

Table 1. Definitions of terms used to describe governance levels.

Note: all definitions are adapted from Setzer (Reference Setzer2013), drawing from aKeohane and Nye (Reference Keohane and Nye1971, p. xi), bAbbott (Reference Abbott2014) or cMarks et al. (Reference Marks, Hooghe and Schakel2008, p. 113).

This article assesses the landscape of regional governments’ transnational action promoting climate change adaptation. In contrast to transnational municipal action, transnational regional initiatives are few and provide less available analysis (Austin et al., Reference Austin, Ford, Berrang-Ford, Biesbroek, Tosun and Ross2018; Setzer, Reference Setzer2015). Moreover, in contrast to the transnationalization of climate mitigation, there are fewer transnational adaptation initiatives and there is scarce examination of the transnationalization of adaptation governance (Dzebo & Stripple, Reference Dzebo and Stripple2015). Addressing these gaps, we examine and discuss the RegionsAdapt initiative (Regions4, 2019), a transnational commitment established by regional governments to support and report efforts on adaptation at the subnational, state and regional level.

The selection of the case was purposeful. We mapped the existing regional and municipal networks that are involved in climate change action, highlighting those that address adaptation. RegionsAdapt is the first global commitment to support and report on adaptation efforts at the state and regional level. The case study combined document analysis (including reports and websites), an interview with the project manager of the initiative and a survey with 33 regional governments, carried out by the first two authors between July and September 2019 (Sainz de Murieta & Setzer, Reference Sainz de Murieta and Setzer2019). While the survey aimed to explore the extent to which adaptation is being addressed as a multilevel governance challenge in the different phases of the adaptation policy-making process, it also addressed the benefit of horizontal collaboration through transnational initiatives and networks such as RegionsAdapt.

Adapting to climate change at the regional level is crucial. However, we suggest that the transnationalization of adaptation governance contributes to the advancement of adaptation measures on the ground and at the same time improves the visibility, aggregation and monitoring of such action globally. We also suggest that developing adaptation tracking systems and incorporating adaptation into platforms such as the Global Climate Action portal could motivate further mobilization and accountability on the topic of transnational adaptation.

The article is structured as follows: we begin Section 2 by justifying the focus on regional governments; we highlight reasons why regional governments can play an important and strategic role in climate change adaptation. We then explore the transnationalization of regional governments’ action. As the extent to which climate adaptation is governed transnationally has not been well explored, we refer to the conceptualization of transnationalization of adaptation governance developed by Dzebo and Stripple (Reference Dzebo and Stripple2015). Drawing upon the three key elements that characterize the transnationalization of adaptation governance, in Section 3 we explore the RegionsAdapt initiative as a primary example of a transnational climate change initiative, promoting regional adaptation in the post-Paris context. Finally, in Section 4, we discuss how the transnationalization of climate adaptation aptly illustrates the opportunities and challenges related to promoting, measuring and monitoring adaptation action.

2. Regional governments and transnational action

2.1. Regionalization: climate adaptation action on the ground

Adaptation to climate change is widely recognized as a multilevel governance challenge (Bauer & Steurer, Reference Bauer and Steurer2014; Persson, Reference Persson2019; Sainz de Murieta & Setzer, Reference Sainz de Murieta and Setzer2019). The important role of regional and local governments in meeting this challenge was reaffirmed by the Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015, at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). On this occasion, the UNFCCC process integrated a bottom-up approach into the international climate process for the first time (Falkner, Reference Falkner2016). The Paris Agreement officially recognized non-state actorsFootnote i as playing a key role in climate governance (Hale, Reference Hale2016), explicitly recognizing “the importance of the engagements of all levels of government and various actors, in accordance with respective national legislations of Parties, in addressing climate change” (UNFCCC, 2015, Preamble).

Alongside these developments, regional and local governments have been committing to a wide range of climate actions in their own right. The broad array of over 22,000 climate actions reported to the UNFCCC's Global Climate Action portal includes 11,088 actions taken by 9465 cities and 756 actions taken by 278 regions (Global Climate Action, 2019). The pledges range from those pledging to directly reduce their own greenhouse emissions to those promising to develop strategies for adaptation and resilience or providing private finance. Overall, however, the majority of pledges remain focused on emission reductions.

Regional governments across the world address climate change through policies, legislation and direct action (Austin et al., Reference Austin, Ford, Berrang-Ford, Biesbroek, Tosun and Ross2018; Bierbaum et al., Reference Bierbaum, Smith, Lee, Blair, Carter, Chapin and Verduzco2013; Farber, Reference Farber2014). Regional adaptation action aims to reduce weather- and climate-related vulnerability and exposure, as well as increase resilience, in urban and rural areas. Options include building seawalls, implementing cooling centres and green infrastructure, establishing resilient water and urban ecosystem services, urban and peri-urban agriculture and adapting buildings and land use through regulation and planning (Allen et al., Reference Allen, de Coninck, Dube, Hoegh-Guldberg, Jacob, Jiang, Zickfeld, Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pörtner, Roberts, Skea, Shukla and Waterfield2018).

Regional governments hold a particularly important position in developing and implementing climate adaptation strategies. First, they have the authority to act in legal domains that are important for climate change adaptation, such as energy, transportation, land use, housing, disaster management and natural resources (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Chapman Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair-Rosenfield2016; Kaswan, Reference Kaswan2013), as well as health care and public health (Austin et al., Reference Austin, Ford, Berrang-Ford, Biesbroek, Tosun and Ross2018; Blank & Burau, Reference Blank and Burau2014). Some regional governments are able to legislate in the absence of federal legislation (Hofsmeister, Reference Hofsmeister2012). Even where central governments retain major responsibilities, the jurisdiction of adaptation policies often falls within the responsibility of regional and local levels of governance (Somanathan et al., Reference Somanathan, Sterner, Sugiyama, Chimanikire, Dubash, Essandoh-Yeddu, Zylicz, Edenhofer, Pichs-Madruga, Sokona, Farahani, Kadner, Seyboth and Minx2014, p. 1152). Regional governments can also collaborate with other subnational governments, countries and jurisdictions. Examples of regional collaboration across national borders are California's Intergovernmental Working Group for the Climate Action Team – Collaboration on Climate Change (ICAT, 2018) and the Québec–California Carbon Market partnership through the Western Climate Initiative, which notably contributes to financing adaptation measures.

Second, regional governments constitute a key nexus between national and local governments. Galarraga et al. (Reference Galarraga, Gonzalez-Eguino and Markandya2011) refer to the ‘paradox of the lent target’ to describe situations in which national governments design and agree upon climate goals that regions are actually in charge of implementing. Similarly, regions are an essential player in integrating cities’ and metropolitan areas’ climate action with efforts undertaken at the national level, while also taking rural and urban realities into account. Therefore, the existent architecture and coordination between national or federal governments on one side and states or regional governments on the other are critical to ensuring effective climate policy across scales (Galarraga et al., Reference Galarraga, Gonzalez-Eguino and Markandya2011). Research suggests that this system of divided powers can also benefit adaptation action (Casado-Asensio & Steurer, Reference Casado-Asensio and Steurer2016; Steurer & Clar, Reference Steurer and Clar2018).

Third, regional governments play a fundamental role in ensuring concrete results from adaptation actions. Since adaptation is typically location specific, adaptation strategies need to consider the specific territories where adaptation challenges occur (Adger et al., Reference Adger, Arnell and Tompkins2005). This capacity for implementation arises from the entrepreneurship of regional governments (Anderton & Setzer, Reference Anderton and Setzer2018) and their capacity – similar to other non-state actors – to foster policy innovation through experimentation and capacity building (Chan et al., Reference Chan, van Asselt, Hale, Abbott, Beisheim, Hoffmann and Widerberg2015).

2.2. Transnationalization: regional climate action across borders

In addition to the goals that they commit to and the action that they take on the ground, regional governments steer behaviour towards shared goals by engaging with other regional governments and actors across borders. Scholars drawing upon a ‘paradiplomacy’ framework suggest that regional action across boarders promotes the culture and identity of states, regions and provinces externally (Duran, Reference Duran2011). For Soldatos (Reference Soldatos, Brown and Fry1993), the international activity of regional governments is the result of factors such as the regionalization of the economy and the advancement of communications and democratization actions. In the environmental and climate change sphere, regional action across borders tends to occur through or with the support of transnational regional networks (TRNs) (Chaloux & Paquin, Reference Chaloux, Paquin, Bruynickx, Happaerts and van der Brande2012; Eatmon, Reference Eatmon2009). Regions4 (formerly the Network of Regional Governments for Sustainable Development; nrg4SD), R20 Regions of Climate Action and The Climate Group are TRNs whose key mission is to address climate change (see Table 2 for a list of TRNs). These networks represent regional governments vis-à-vis international organizations, influence multilateral decision-making, foster horizontal cooperation and stimulate policy learning (Happaerts et al., Reference Happaerts, Van den Brande and Bruyninckx2011; Rei et al., Reference Rei, Cunha and Setzer2013).

Table 2. Networks of subnational governments involved in climate governance.

Source: Authors, based on information from the UNFCCC-admitted non-governmental organizations (https://unfccc.int/process/parties-non-party-stakeholders/non-party-stakeholders/admitted-ngos/list-of-admitted-ngos), cities and regions/Local Governments and Municipal Authorities (LGMA) Constituency (https://www.cities-and-regions.org) and Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments (https://www.global-taskforce.org).

Compared to transnational municipal climate networks, TRNs are fewer and less visible.Footnote ii Transnational municipal climate action has been the subject of great scholarly interest. Analyses are found in the fields of international relations (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011), international law (Abbott, Reference Abbott2014; Heyvaert, Reference Heyvaert2013) and geography (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012). Cities’ transnational climate action has been studied through the lens of multilevel governance frameworks (Bouteligier, Reference Bouteligier2013; Gordon & Johnson, Reference Gordon and Johnson2018; Toly, Reference Toly2008). Bulkeley et al. (Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012) identify five main functions of transnational climate change initiatives: agenda setting, information sharing, capacity building, soft and hard forms of regulation and policy integration. Participation in transnational municipal networks (TMNs), in particular, has been found to provide assistance to cities (Lee & Koski, Reference Lee and Koski2014), to play a catalytic role in climate mitigation (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011) and to support local adaptation (Fünfgeld, Reference Fünfgeld2015). The most prominent networks are ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability and the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (see Table 2 for a list of TMNs). In a number of cases, city networks become formal and institutionalized governance structures, facilitating city-to-city and city-to-other actors cooperation, or ‘city diplomacy’ (Acuto et al., Reference Acuto, Morissette and Tsouros2017).

These transnational climate change initiatives are often ‘orchestrated’ (i.e., initiated, guided, broadened and strengthened) by states or intergovernmental organizations (Bäckstrand & Kuyper, Reference Bäckstrand and Kuyper2017; Hale & Roger, Reference Hale and Roger2014). A specific coordination mechanism can, however, be observed in subnational governments’ transnational climate action. Under the UNFCCC system, both regional and local authorities and their networks are represented by the Local Governments and Municipal Authorities (LGMA) Constituency. The LGMA works on behalf of the Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments (https://www.global-taskforce.org), a coordination and consultation mechanism that brings together the major international networks of local governments to undertake joint advocacy work relating to global policy processes. The Global Taskforce was set up in 2013 to bring the perspectives of local and regional governments to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), climate change agenda and the New Urban Agenda. Regional and local governments are the only UN non-state actors to have a mechanism such as the Global Taskforce to develop and coordinate inputs into policy processes.

For the purposes of this article, it is worth noting that the objectives of regional and municipal climate networks have changed in similar ways over time. When the first subnational climate networks were established in the early 1990s, their main objective was to promote the engagement of cities and regions in climate change matters and to get leaders to establish climate policies and regulation (Kern & Bulkeley, Reference Kern and Bulkeley2009; Schroeder et al., Reference Schroeder, Burch and Rayner2013). In this initial phase, networked municipal and regional arrangements were considered to be beneficial to policy-making (Bauer & Steurer, Reference Bauer and Steurer2014; Zeppel, Reference Zeppel and Cadman2013). With time, the expectations of networks and policy-makers for outcomes have evolved, and both TMNs and TRNs now demand that the actions of their member cities and regions are traceable and continue to advance. This evolution from a discursive to a stronger policy approach has been observed by Gordon (Reference Gordon2016, p. 175) in relation to C40's strategies: “[I]f the mantra of the C40 circa 2009 was ‘cities act, while nations talk’ then by 2014 it had without doubt become, ‘if you can't measure it, you can't manage it’.” In response, climate action from cities, regions and companies started to be aggregated in voluntary platforms (e.g., see Data Driven Yale et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the monitoring and reporting processes of these platforms is still insufficient and mitigation-focused (Bansard et al., Reference Bansard, Pattberg and Widerberg2017; Bertoldi et al., Reference Bertoldi, Kona, Rivas and Dallemand2018). At the same time, there have been consistent calls for improved approaches to systematically assessing adaptation progress (Berrang-Ford et al., Reference Berrang-Ford, Biesbroek, Ford, Lesnikowski, Tanabe, Wang and Heymann2019).

2.3. Transnationalization of adaptation

The extent to which climate adaptation is governed transnationally has not been well explored. Adaptation action tends to be understood as a ‘localized’ phenomenon. In a systematic literature review of documents commenting on the localness of adaptation, less than a tenth questioned whether adaptation is really a local issue (Nalau et al., Reference Nalau, Preston and Maloney2015). However, adaptation is a multilevel, multiactor endeavour that “requires high degrees of collaboration, facilitated through effective partnerships, in order to produce positive adaptation outcomes and avoid maladaptation” (Fünfgeld, Reference Fünfgeld2015, p. 70). Moreover, the Paris Agreement explicitly established the need to “establish a global goal on adaptation” (UNFCCC, 2015, Article 7.1). Recognizing that defining global adaptation goals entails overcoming technical, scientific and political barriers (Magnan & Ribera, Reference Magnan and Ribera2016), scholars have been calling for enhanced global adaptation governance (Bierman & Boas, Reference Bierman, Boas, Biermann, Pattberg and Zelli2010; Persson, Reference Persson2019).

Opening up the possibility of new institutions, processes and actors to govern adaptation, Dzebo and Stripple (Reference Dzebo and Stripple2015) coined the term ‘transnational adaptation governance’. Transnational adaptation initiatives are characterized by their scope (i.e., initiating actors, organizational form and governance structure), (ii) institutionalization (i.e., how the projects emerge and maintain activity) and functions (i.e., the specific governance functions that the projects undertake). Dzebo and Stripple applied this conceptualization to a dataset of 26 transnational adaptation projects, driven by recipient countries in collaboration with international organizations (UN agencies and regional development banks) and managed by multilateral funds that target climate change. But while Dzebo and Stripple (Reference Dzebo and Stripple2015) provide a first insight into the types of transnational adaptation projects initiated by national governments, instances of adaptation occurring at the local and regional level are not included in their analysis. Moreover, since their study, several new transnational initiatives have been launched or have gained momentum (Persson, Reference Persson2019).

Reflecting the multilevel character of climate adaptation, transnational adaptation governance is also taking place at the subnational level. Indeed, over the past decade, some of the leading TMNs and TRNs have developed and implemented climate change adaptation and urban resilience programmes, including a range of adaptation capacity-building programmes, guidebooks and conferences (see Table 2). Fünfgeld (Reference Fünfgeld2015) provides an overview of six TMNs that focus wholly or in part on climate mitigation and adaptation (ICLEI, Energy Cities, Climate Alliance, C40, Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network and 100 Resilient CitiesFootnote iii), whilst Papin (Reference Papin2019) focuses on the adaptation efforts of the 100 Resilient Cities network. No such analysis has yet been made of TRNs’ efforts to address adaptation.

However, barriers and ongoing challenges limit regional governments’ ability to respond effectively to adaptation (Biesbroek et al., Reference Biesbroek, Klostermann, Termeer and Kabat2013) and, ultimately, to engage in transnational action. Challenges include a paucity of financial and human resources, a lack of integration and coordination between levels of government, insufficient research, management practices and tools to monitor adaptation effectiveness and, critically, a lack of medium- to long-term adaptation planning (nrg4SD, 2017). At the transnational level, initiatives focusing on climate resilience and adaptation have also suffered from limited effectiveness. A review of 52 climate initiatives launched in 2014 showed that after 2 years a majority of adaptation objectives were still only intentions (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Falkner, Goldberg and van Asselt2018), and the situation is shown to have seen little change in two more recent evaluations (Chan & Amling, Reference Chan and Amling2019; Dzebo, Reference Dzebo2019).

3. RegionsAdapt, a transnational climate change adaptation initiative

The literature review above shows that scholarship has been studying transnational municipal action aimed at promoting greenhouse gas emission reductions (mitigation), whilst leaving the transnational regional action directed at increasing resilience (adaptation) unexplored. The RegionsAdapt initiative is a primary example of a transnational climate change initiative exclusively promoting regional adaptation in the post-Paris context. RegionsAdapt complies with all three conditions that, according to Bulkeley et al. (Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012), characterize transnational climate change initiatives: it responds to the challenges of climate change (in this particular case, the focus is on adaptation); it operates transnationally (across 27 countries, involving 65 subnational governments); and it pursues action (on adaptation) among its members. To explore central aspects of the RegionsAdapt initiative, in this section we draw upon Dzebo and Stripple's (Reference Dzebo and Stripple2015) conceptualization of transnational adaptation governance, emphasizing: (1) its initiating actors, organizational form and governance structure (scope); (2) the formation of the project and how it maintains activity (institutionalization); and (3) the specific governance functions that the project undertakes (function).

3.1. Scope

RegionsAdapt is the first transnational climate change initiative established to support and report on adaptation efforts at the state and regional level. It was launched in Paris during COP21 with the objective of establishing a cooperative framework for regions to exchange experiences, challenges and best practice related to their climate change adaptation actions (Rei & Pinho, Reference Rei and Pinho2017). The initiative is maintained by Regions4 (formerly nrg4SD), a global network that represents regional governments in the fields of climate change, biodiversity and sustainable development. However, not all RegionsAdapt members are necessarily also Regions4 members.

The initiative covers all inhabited continents, and the 230 million people represented by the participating regions constitute approximately 3% of the world's population. The member regions are heterogeneous in size, population, policy capacity and level of climate progress (see Appendix 1 for a list of members). While studies identify North–South gaps in the participation in and leadership of climate actions (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Falkner, Goldberg and van Asselt2018), the opposite occurs in RegionsAdapt. To begin with, the initiative was initially crafted and promoted by Catalonia and Rio de Janeiro, a North–South partnership. The state of Rio de Janeiro provided a particularly important input over the design of the initiative and offered a full-time employee to serve as project manager during the first year of the initiative. Moreover, 34 of RegionAdapt's member regions are located in Latin America and 15 are located in Africa. This is followed by North America and Europe with 12 regions in each, and Oceania and Asia, each with 2. The distribution helpfully reflects the fact that, in various respects, climate action in developing countries can be considered more urgent (Mendelsohn et al., Reference Mendelsohn, Dinar and Williams2006).

What these regions share is a common interest in addressing climate change and in developing adaptation policies and measures in particular, and doing so in a networked rather than isolated way. By joining the RegionsAdapt initiative, regional governments commit to annually disclose their data on climate risks and adaptation through the CDP's (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) States and Regions questionnaire. Each year, Regions4 publishes a summary of the data to inform on regional governments’ ambitious actions to adapt to climate change. The annual disclosure process helps RegionsAdapt members to better understand the risks they face from climate change, measure their progress and learn from each other's adaptation actions (Regions4, 2019).

3.2. Institutionalization

Bulkeley et al. (Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012) found that transnational climate change initiatives usually exhibit some level of institutionalization, which could include soft formulas, such as voluntary affiliation and a registry of membership, or stronger rules, such as the requirement to pay membership fees or to comply with certain objectives or actions. RegionsAdapt membership is voluntary, free and open to all governments between the national and local scales. Regional governments can join regardless of their progress in the design and implementation of climate policies, but once on board they are required to respond to specific objectives and to ratchet up their ambition, as previously described. While transnational climate change initiatives do not usually have a formal structure, RegionsAdapt relies on the support of Regions4, which acts as secretariat and helps with the coordination of the initiative.

3.3. Functions

Information sharing and capacity building are at the core of most transnational initiatives dealing with climate change (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012; Dzebo & Stripple, Reference Dzebo and Stripple2015). The survey conducted with 33 regional governments confirmed that regional authorities benefit from the exchange of experiences and best practice on adaptation, promoted by TRNs. At the same time, they indicated that financial constraints, followed by weak technical capacity and resources, were the main barriers to adaptation during both the planning and implementation phases (Sainz de Murieta & Setzer, Reference Sainz de Murieta and Setzer2019). Again, in this regard, RegionsAdapt has an important function to perform, promoting cooperation and the dissemination of knowledge among its members and supporting regions through different capacity-building activities. Regions confirmed in the survey that being part of a TRN contributed to accessing funds (e.g., via participation in research projects as partners or observers), participating in international conferences and receiving expert support.

RegionsAdapt was envisioned by regional government representatives, and the initiative's areas of work reflect the areas of interest of its founding members. At its inception, the founding members identified seven priority areas for the initiative to work on: water resources and management; resilience and disaster risk reduction; agriculture and zootechnics; forestry, protected areas and biodiversity; infrastructures and land planning; economic impacts and opportunities; and social impacts and adaptation. Each one of these areas is discussed in a working group, which is coordinated by one or two member regions. The working groups meet virtually (through platforms such as GoToMeeting™) and their activity varies depending on their participants. The groups aim to function as a platform for sharing knowledge, experiences and good practices. They should also aim to identify opportunities for joint funding initiatives and projects, although according to Regions4 staff this objective has not yet been met.

Most transnational climate change initiatives also involve some form of regulation, even if it is voluntary, such as the establishment of targets, rules or monitoring requirements designed to delimit and guide members (Andonova et al., Reference Andonova, Betsill and Bulkeley2009; Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012). The development of monitoring and evaluation processes has been identified as key to enabling learning and adaptive management, as well as for tracking the progress on adaptation at the regional scale (Preston et al., Reference Preston, Westaway and Yuen2011). As previously mentioned, a recent trend within transnational climate initiatives has been not only to expect commitments, but also to ask participants to report progress and to sustain ambition.

RegionsAdapt follows this logic, with members agreeing to a series of commitments over a six-year time horizon. In the first two years (Phase 1), regions agree to prioritize adaptation by reviewing their adaptation strategies or plans, or adopting a new one, taking action on at least two of the seven key priority areas mentioned above, and monitoring and measuring their progress. As previously mentioned, the reporting process takes place annually, using the CDP States and Regions data disclosure platform, and RegionsAdapt produces annual reports with the results (nrg4SD, 2016, 2017, 2018; Regions4, 2019). Governments that successfully comply with Phase 1 commitments are invited to join Phase 2, which entails two additional responsibilities over the following two-year period: identify opportunities or gaps in their existing adaptation plans or strategies; and increase the sectoral scope for action by taking specific action in three of the initiatives’ priority areas. In Phase 3, planned for the final two-year period, regions commit to providing evidence of action taken to address the gaps identified in Phase 2. This should coincide with the second round of higher-ambition climate pledges (2020) under the Paris Agreement.

Another function performed by transnational climate change initiatives is setting new climate agendas and policies (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Bäckstrand, Betsill, Compagnon, Duffy and VanDeveer2012; Fünfgeld, Reference Fünfgeld2015). RegionsAdapt provides opportunities for experimentation with new adaptation policies in regions that represent different environmental, social and economic contexts. In fact, RegionsAdapt is testing a new approach to evaluate climate adaptation plans. The development of monitoring and evaluation processes has been identified as critical for enabling learning and adaptive management, as well as for tracking progress on adaptation (Preston et al., Reference Preston, Westaway and Yuen2011). In order to facilitate this process, as well as to enable comparability and benchmarking across regions, the RegionsAdapt Secretariat recommends that regions use a common evaluation tool developed by Olazabal et al. (Reference Olazabal, Galarraga, Ford, Sainz de Murieta and Lesnikowski2019).

Lastly, transnational climate change initiatives can also fulfil a policy integration function. While adaptation should occur at multiple scales and address different sectors (Dewulf et al., Reference Dewulf, Meijerink and Runhaar2015), mainstreaming adaptation into national policies remains a challenge (Preston et al., Reference Preston, Westaway and Yuen2011). Although not an explicit aim of the initiative, some elements of RegionsAdapt could stimulate policy integration with the national and international levels of governance. For instance, the working groups assess specific sectors that are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts and engage with policy-makers at the national level. In addition, RegionsAdapt has been trying to help integrate adaptation into other agendas, such as the SDGs and biodiversity protection (Nilwala, Reference Nilwala2017).

4. Discussion

The bottom-up approach established by the Paris Agreement consolidated a new picture of climate governance: subnational actors and national governments are to ‘share the burden’ of climate action (Chan et al., Reference Chan, van Asselt, Hale, Abbott, Beisheim, Hoffmann and Widerberg2015), and adaptation is not only to take place locally, but also transnationally (Persson, Reference Persson2019). The analysis of the RegionsAdapt initiative based on its scope, institutionalization and functions suggests that transnational adaptation governance not only incentivizes the promotion of adaptation measures on the ground, but also contributes to the process of tracking the progress of such action. However, there are substantial challenges to the development and implementation of adaptation action, which include amassing sufficient political will and accessing funding (Biesbroek et al., Reference Biesbroek, Klostermann, Termeer and Kabat2013).

Because of their scope, institutionalization and functions, transnational adaptation actions established. Transnational adaptation actions established by initiatives such as RegionsAdapt aptly illustrate three opportunities for adaptation governance.

First, transnational adaptation initiatives help promote awareness of adaptation. By the end of the first two-year period of RegionsAdapt, 35 governments reported their adaptation initiatives through the CDP platform; more than two-thirds of them had carried out a risk or vulnerability assessment in their territories. This suggests that regional governments in the initiative are well aware of the need to prepare for the impacts of climate change. The number of regions that have adaptation plans also increased significantly: 91% of RegionsAdapt members are developing (26%) or have already adopted (65%) an adaptation plan or strategy, and more than 200 adaptation actions have been reported. Some of the few regions that did not establish a specific plan or strategy have adaptation policies integrated into broader environmental (or other) plans or strategies, whilst others simply lack resources or capacity (nrg4SD, 2017).

The reporting of climate actions taken emphasizes the potential learning opportunities across regional governments, particularly for regions with scarce financial and/or human resources. The local nature of adaptation policies can make it particularly challenging to transfer actions between regions with different institutional, social and geographical contexts, and in most cases different degrees of transfer can be expected (Benson & Jordan, Reference Benson and Jordan2011; Wolman & Page, Reference Wolman and Page2002). Yet, subnational governments can be important transfer agents, benefitting from a number of linked processes, including globalization and devolution (Betsill & Bulkeley, Reference Betsill and Bulkeley2004). Moreover, the role transnational climate change initiatives play in capacity building, even if considered a ‘softer form of governance’, should not be underestimated (Dzebo & Stripple, Reference Dzebo and Stripple2015). Most RegionsAdapt participants met their three Phase 1 commitments. More than 80% have prioritized adaptation actions by adopting a plan or strategy or by reviewing an existing plan during the two-year commitment period. Every region presented actions in at least one of the key priority topics and 85% of them reported on their progress.

Measuring and monitoring the effectiveness of an adaptation strategy or adaptation decision depends on how that action meets the objectives of adaptation and how it affects the ability of others to meet their adaptation goals (Adger et al., Reference Adger, Arnell and Tompkins2005). While the existence of climate adaptation policies has been used as an indicator of progress (e.g., Araos et al., Reference Araos, Berrang-Ford, Ford, Austin, Biesbroek and Lesnikowski2016), having a policy is not enough to assess whether these plans are being successfully implemented and whether they are producing the expected outcomes. In this context, the assessment and evaluation of outcomes is a crucial supplement to simple output measurement (Berrang-Ford et al., Reference Berrang-Ford, Biesbroek, Ford, Lesnikowski, Tanabe, Wang and Heymann2019). Learning processes that provide feedback on adaptation planning are key to the adaptive management cycle, providing a basis for readjusting, revising, redefining or changing to alternative policy or strategy pathways (Olazabal et al., Reference Olazabal, Galarraga, Ford, Sainz de Murieta and Lesnikowski2019). This is explicitly acknowledged by RegionsAdapt, as its members agree to evaluate existing adaptation plans during Phase 2 and provide evidence in Phase 3 of action that addresses the gaps identified. Although overlapping instruments are a problem in many policy areas (Goulder & Stavins, Reference Goulder, Stavins, Fullerton and Wolfram2012), this does not justify a failure to address the challenge of effective integration in bottom-up approaches. Indeed, because of the local nature of adaptation, issues of overlapping, double counting of efforts or lack of coordination are much less of a problem in the field of adaptation than in mitigation.

But transnational regional initiatives such as RegionsAdapt also face challenges, particularly difficulties with fostering action and keeping momentum in a context of weak institutionalization and limited resources. Policy integration with broader initiatives is also unclear. While the UNFCCC recognizes that non-state actors are a fundamental part of the process and that efforts from multiple levels should be integrated (Sainz de Murieta et al., Reference Sainz de Murieta, Galarraga and Sanz2018), subnational governments are still largely excluded from international negotiation processes (Galarraga et al., Reference Galarraga, Sainz de Murieta, França, Averchenkova, Fankhauser and Nachmany2017), and the ‘lent target paradox’ (Galarraga et al., Reference Galarraga, Gonzalez-Eguino and Markandya2011) is even more evident in the case of adaptation. How to solve this paradox is still unclear, as the UN is, by definition, designed to represent nation states. Small steps have been taken with initiatives such as the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action, which aims to enable collaboration between state and non-state actors to boost climate action, but there is still much to be done in order to effectively account for non-state actors in the UNFCCC process. Incorporating adaptation action into the Global Climate Action portal would help to provide a broad overview of adaptation initiatives (as it currently does for mitigation) and could motivate further mobilization and accountability on the topic of transnational adaptation. The adoption of conceptual frameworks to track climate change adaptation, such as the one proposed by Berrang-Ford et al. (Reference Berrang-Ford, Biesbroek, Ford, Lesnikowski, Tanabe, Wang and Heymann2019), could further support the systematic and consistent tracking of adaptation by governments. However, adding initiatives into data platforms is not enough. As Kuyper et al. (Reference Kuyper, Linnér and Schroeder2017) suggest, it is no longer a matter of whether and how to include non-state actors within the climate change governance arena, but rather how to define an architecture that maximizes their contribution.

5. Conclusion

Although adaptation has become a mainstream topic within the global regime on climate change, gaps remains between mitigation–adaptation action, as well as between local–regional–transnational approaches. Initiatives such as RegionsAdapt help to address these gaps by framing adaptation as a transnational matter, and also as a tool to inspire and support regional governments to take concrete action, collaborate and report on climate change adaptation efforts. This is even more important if we take into account the fact that regional governments are often in charge of policy domains that are very relevant for adaptation.

Transnational climate initiatives fulfil a number of functions that may prove useful in promoting adaptation action: stimulating information sharing and building capacity; guiding its members with different forms of regulation; setting new climate agendas; and/or improving policy integration across scales and sectors. Regional governments wishing to engage with the Paris Agreement's commitments and to report their actions benefit from joining transnational adaptation initiatives – RegionsAdapt or similar initiatives. It is inspiring to see the commitment that regional governments are ready to take in order to address the issue of climate change adaptation. How this initiative will contribute to the UNFCCC process and efforts on adaptation remains to be seen, but it is a challenge that should be addressed sooner rather than later.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sander Chan, Sara Kupka and Vanessa Pulgarin for very helpful comments that helped to improve this manuscript.

Author contributions

Fernando Rei and Mariângela Mendes Lomba Pinho conceived the study. Joana Setzer and Elisa Sainz de Murieta designed the study and conducted data gathering. Joana Setzer, Elisa Sainz de Murieta and Ibon Galarraga wrote the article.

Financial support

Joana Setzer acknowledges financial support from the British Academy through a Postdoctoral Fellowship, as well as the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) via the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy. Elisa Sainz de Murieta acknowledges funding from the Basque Government (grant no. POS_2018_2_0027). Ibon Galarraga is grateful for the financial support from the Research Council of Norway under the project Strategic Challenges in International Climate and Energy Policy (CICEP). Elisa Sainz de Murieta and Ibon Galarraga acknowledge the financial support of the Basque Government through the BERC 2018–2021 programme and of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness through the María de Maeztu excellence accreditation MDM-2017-0714 of the Basque Centre for Climate Change.

Conflicts of interest

Joana Setzer worked at Regions4 (formerly nrg4SD) as an international affairs coordinator when the RegionsAdapt initiative was launched (between 2014 and 2015). Joana Setzer and Fernando Rei are members of Regions4's advisory board.

Appendix 1: List of RegionsAdapt members

The 27 founding members of RegionsAdapt have been joined by several other signatories who adhered to the initiative. Currently, the initiative counts 61 members from all continents, including 56 regional governments and 5 national associations of regional governments.

AJUDEPA (Paraguay)

Amambay (Paraguay)

ANCORE (Chile)

ANGR (Peru)

Araucanía (Chile)

Australian Capital Territory (Australia)

Azuay (Ecuador)

Basque Country (Spain)

Bolivar (Ecuador)

British Columbia (Canada)

Caldas (Colombia)

California (USA)

Canary Island (Spain)

Catalonia (Spain)

Ceará (Brazil)

Central Department (Paraguay)

Cerro Largo (Uruguay)

Chaco Tarijeño (Bolivia)

CONGOPE (Ecuador)

Cordillera (Paraguay)

Council of Governors of Kenya Cusco (Peru)

Dakhla-Oued Ed Dahab (Morocco)

Esmeraldas (Ecuador)

Fatick (Senegal)

Fès-Meknès (Morocco)

Goiás (Brazil)

Gossas (Senegal)

Imbabura (Ecuador)

Jalisco (Mexico)

Kaffrine (Senegal)

KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa)

Lombardia (Italy)

Manabí (Ecuador)

Morona Santiago (Ecuador)

Napo (Ecuador)

O'Higgins (Chile)

Orellana (Ecuador)

Parana (Brazil)

Pastaza (Ecuador)

Pichincha (Ecuador)

Prince Edward Island (Canada)

Québec (Canada)

Rabat-Salé-Kénitra (Morocco)

Reunion Island (France)

Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)

Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil)

Risaralda (Colombia)

Roraima (Brazil)

Saint Louis (Senegal)

Santa Elena (Ecuador)

Santander (Colombia)

São Paulo (Brazil)

South Australia (Australia)

Sud-Comoé (Ivory Coast)

Tocantins (Brazil)

Tombouctou (Mali)

Vermont (Canada)

Wales (UK)

Western Province (Sri Lanka)

Zou (Benin)

Source: List of RegionsAdapt members retrieved from https://www.regions4.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/R4_RegionsAdapt2016_BriefReport.pdf.