Impact statement

This review synthesizes the current evidence base for psychological interventions for children aged 5–12 years and their caregivers to inform the design of effective, feasible and scalable services for children of this age group and their caregivers in low- and middle-income countries, humanitarian settings and other contexts of adversity globally. Findings align with previous reviews demonstrating the limited evidence for interventions with younger children, but extend on these by outlining current knowledge with regard to the format and content of interventions that have shown promise. It is relevant to researchers and practitioners working to reduce the mental health treatment gap in this neglected age group.

Social media summary

This review summarizes evidence for interventions to address emotional and behavioral difficulties in children aged 5–12 years.

Introduction

Middle childhood is characterized by important social, emotional and cognitive changes with wide-ranging long-term consequences for human development. Children in this age group experience significant changes in executive functioning, including attentional control, working memory, inhibition, information processing, goal-setting and emotional regulation (Del Giudice, Reference Del Giudice2018). The development of these social, emotional and cognitive skills aids interpersonal interaction and provides a foundation for healthy relationships, school performance, productivity at work and better overall health and well-being (Del Giudice, Reference Del Giudice2018). Middle childhood is also a period of growing independence, and the establishment and maintenance of peer and other external relationships (Nuru-Jeter et al., Reference Nuru-Jeter, Sarsour, Jutte and Thomas Boyce2010). Caregiving factors, such as closeness of relationship, are major influences on child mental health at this time (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Scott, McCormick and Weinberg2014); however, this is also the time when a child’s environment expands to outside the home, and relationships within school and other community settings become increasingly important (Sørlie et al., Reference Sørlie, Hagen and Nordahl2021). It is well established that exposure to risk and protective factors during this period influences mental health and developmental trajectories into adolescence and adulthood (Feinstein and Bynner, Reference Feinstein and Bynner2004), yet unfortunately globally, over 356 million children live in poverty (Silwal et al., Reference Silwal, Engilbertsdottier, Cuesta, Newhouse and Steward2020), and more than 43 million are forcibly displaced due to armed conflict and other humanitarian emergencies (UNHCR, 2023), risking disruption of their development and detrimental mental health outcomes.

Often, emotional and behavioral difficulties emerge or are first identified during the middle childhood period, including both internalizing and externalizing problems. Approximately one in three mental disorders (including depression, anxiety and behavioral disorders) have their onset before 14 years of age (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Il Shin, Kirkbride, Jones and Kim2022), and more than 250 million children and adolescents worldwide experience mental health disorders (Stelmach et al., Reference Stelmach, Kocher, Kataria, Jackson-Morris, Saxena and Nugent2022). Children and young people living in contexts of adversity face significantly greater risks of mental health difficulties (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019; Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Boyle, Fazel, Ranasinha, Gray, Fitzgerald, Misso and Gibson-Helm2020).

Despite the high burden of mental disorders, and the demonstrated return on investment of timely treatment (Stelmach et al., Reference Stelmach, Kocher, Kataria, Jackson-Morris, Saxena and Nugent2022; UNICEF, 2023), there remains a vast global mental health treatment gap, with the majority of people needing treatment not receiving minimally adequate care. This gap is estimated at up to 90% in low-income countries, with children and adolescents particularly neglected in services (WHO, 2022). Major drivers of this treatment gap include lack of funding, particularly for child and adolescent mental health, (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Li and Patel2018), and under-resourced professional workforces, with an average of two mental health professionals per 100,000 population in low-income countries (compared to 60 in high-income countries [HICs]) (WHO, 2021). Other factors include barriers such as lack of parental knowledge and understanding of mental health problems and support, high costs and low accessibility of services, lack of trust in services and limited health worker training in identifying and managing child mental problems (O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Harvey, Howse, Reardon and Creswell2016; Reardon et al., Reference Reardon, Harvey, Baranowska, O’brien, Smith and Creswell2017). Efforts to address this gap include integrating mental health strategies across sectors, community-based service delivery and task-shifting approaches that involve training nonspecialists to deliver psychological support with supervision, allowing specialists to focus on complex cases.

There is increasing evidence for the safety and effectiveness of such nonspecialist delivered interventions in a variety of settings, provided systematic adaptations are made for cultural and contextual factors (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017; van Ginneken et al., Reference van Ginneken, Chin, Lim, Ussif, Singh, Shahmalak, Purgato, Rojas-García, Uphoff and McMullen2021). Recently developed intervention packages include the World Health Organization’s Problem Management+ (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015) for adults experiencing distress and Early Adolescent Skills for Emotion (EASE) for 10- to 15-year-olds with internalizing symptoms (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Watts, Carswell, Shehadeh, Jordans, Bryant, Miller, Malik, Brown and Servili2019), which have both shown feasibility and effectiveness in multiple low- and middle-income (LMIC) settings. They are transdiagnostic by targeting broadly defined psychological distress rather than requiring complex assessment and diagnostic procedures, incorporate evidence-based treatment components and are relatively brief. However, corresponding interventions for boys and girls aged 5–12 years in LMICs and humanitarian emergencies remain lacking.

Multiple guidelines recommend identification and referral to psychological interventions for children with emotional and behavioral symptoms (e.g., WHO, 2016; UNICEF, 2021), yet the development of feasible evidence-based nonspecialist interventions that can be delivered at scale is hampered by a lack of evidence. Recent meta-analyses and umbrella reviews have found limited evidence of effective approaches for children in LMICs (Barbui et al., Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton, Gastaldon, Gureje, Hanlon, Jordans, Lund, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Papola, Tedeschi, Tol, Turrini, Patel and Thornicroft2020) and refugee and asylum seeking populations (Turrini et al., Reference Turrini, Purgato, Acarturk, Anttila, Au, Ballette, Bird, Carswell, Churchill, Cuijpers, Hall, Hansen, Kösters, Lantta, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Sijbrandij, Tedeschi, Valimaki and Barbui2019) with even less evidence for the middle childhood age range in particular (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon, Gordon, O’Callaghan, Papola and Peltonen2018). An evidence and gap map (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Perera, Sharma, Ipince, Bakrania, Shokraneh, Sepulveda and Anthony2023) underscored the scarcity of evidence for pre-adolescent years and highlighted the tendency to focus on clinical outcomes rather than broader distress and well-being conceptualizations. Despite potential promise of parenting and family-based interventions in LMICs (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Smallegange, Coetzee, Hartog, Turner, Jordans and Brown2019; Bosqui et al., Reference Bosqui, Mayya, Farah, Shaito, Jordans, Pedersen, Betancourt, Carr, Donnelly and Brown2024), most evaluated programs tend to focus more on universally delivered prevention and promotion, with few targeting children with existing behavioral and emotional difficulties, or families in humanitarian emergencies. Gender differences in response to interventions are currently poorly understood. Accordingly, interventions for children and adolescents, including knowledge of active ingredients and key implementation factors, are recognized as research priorities for mental health in humanitarian settings (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Le, Harrison, Galappatti, Annan, Baingana, Betancourt, Bizouerne, Eaton and Engels2023).

In order to design optimal psychological interventions, there is a need to understand and evaluate elements driving impact. Brown et al. (Reference Brown, de Graaff, Annan and Betancourt2017) conducted a systematic review and treatment component analysis of interventions for young people in LMICs affected by armed conflict. Common treatment components in promising interventions included accessibility promotion, building rapport, homework provision and strategies for maintaining gains and preventing relapse. Specific intervention strategies included psychoeducation, cognitive, exposure, relaxation and expressive techniques like art and dance. Similarly, systematic reviews and treatment component analyses of parenting and family interventions in LMICs (Bosqui et al., Reference Bosqui, Mayya, Farah, Shaito, Jordans, Pedersen, Betancourt, Carr, Donnelly and Brown2024; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Smallegange, Coetzee, Hartog, Turner, Jordans and Brown2019) identified commonly included components of psychoeducation, supporting caregiver coping, teaching caregiver strategies (e.g., praise, reinforcement, logical consequences and modeling), promoting social support, building insight, activity scheduling, communication skills, problem solving and goal setting. A recent series of reviews commissioned by the Wellcome Trust, for preventing and treating depression and anxiety in 14- to 24-year-olds (Wolpert et al., Reference Wolpert, Pote and Sebastian2021) found that potentially promising treatment components include behavioral activation, problem-solving, relaxation techniques like mindfulness, emotion regulation and the use of economic supports to promote mental health. Important implementation factors highlighted included considering group teaching, booster sessions and the capacity of teachers to implement strategies effectively in schools. Unfortunately, the majority of reviews highlight limited quality evidence at the individual treatment component level. Additionally, the extent to which these components have the same feasibility and impact with younger children remains unknown.

Building and expanding on these reviews, we conducted this evidence review to synthesize existing research and practice from both HICs and LMICs on psychological interventions specifically for children aged 5–12 years experiencing emotional and/or behavioral problems, with particular attention to effective components and implementation strategies. We conducted this study to inform the development of a new, evidence-based, scalable intervention designed for delivery by trained and supported nonspecialist providers, for boys and girls experiencing symptoms of emotional and behavioral difficulties, living in LMICs, humanitarian emergencies and other contexts of adversity.

Methods

Design

We conducted an evidence review of intervention evaluations for boys and girls aged 5–12 years with emotional and/or behavioral difficulties living in LMICs specifically, including studies conducted in humanitarian emergencies in LMICs (Strategy 1). Recognizing that the evidence base for psychological interventions in LMICs is limited, this review was supplemented by additional evidence from two sources: i) A review and synthesis of findings from existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses on interventions for emotional and/or behavioral disorders for this age group globally (Strategy 2); ii) A review of current technical guidelines for emotional and behavioral disorders in this age group (Strategy 3). This is not a systematic review, but rather draws from existing available synthesized and non-synthesized evidence for psychological interventions with this age group from a range of sources, to inform recommendations for the design of new interventions.

Search strategies and selection criteria

The search Strategies 1 and 2 were conducted by FB, CL and SS with regular discussion to compare results and discuss inclusion and exclusion. Studies were initially screened for inclusion by FB, CL and SS on the basis of title, abstract and/or information presented in the abstract. In the second stage of screening, studies were screened for inclusion again by FB, CL and SS on the basis of full text, with regular discussions to ensure consistency of inclusion. Strategy 3 searches were conducted by FB and CL separately and included a review of current guidelines relevant for 5- to 12-year-olds. Table 1 outlines full details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the evidence review

Search and synthesis Strategy 1 – LMIC studies

To identify eligible studies, we reviewed reference lists of 23 systematic reviews, 3 Cochrane reviews, 1 unpublished evidence review, 1 umbrella review and 1 evidence gap map (see Supplementary Materials S1 for reviews searched). We screened for evaluation studies that tested a psychological intervention for boys and/or girls aged 5–12 years experiencing emotional or behavioral difficulties, compared to a control group. Systematic reviews were identified through: i) unstructured database searches, ii) searching reference lists of reviews of reviews and recent publications and iii) consultation with authors and colleagues. Additionally, we reached out to relevant authors to enquire about upcoming publications that could be included. Data were extracted and synthesized in narrative format. Expanded information is provided for studies that met the following criteria: sample size n > 50; RCT design; sufficient information on intervention, format and study design to inform future interventions (judged by two reviewers); and significant improvement in treatment group compared to control for at least one relevant outcome.

Search and synthesis Strategy 2 – Global reviews

We searched three sources to identify appropriate systematic reviews and meta-analyses. First, we searched Cochrane library to identify the most recent reviews on interventions for children (no time restrictions). Second, we used systematic search results from two recent internal WHO evidence reviews conducted in 2022. Full search strategies are available in Supplementary Material S2. Studies were initially screened for inclusion based on title, abstract and/or information presented in the abstract. In the second stage of screening, studies were screened for inclusion based on full text, with regular discussions to ensure consistency. Data were extracted and synthesized in narrative format.

Search and synthesis Strategy 3 – Technical guidelines

We conducted an internet search for mental health and psychosocial support technical guidelines relevant for children, along with input from all authors. This was limited to global- or national-level guidelines in English. No date restrictions were applied. They were narratively summarized individually, and then synthesized to provide key recommendations for each type of presentation. Where guidance on pharmacotherapy was included, this was not synthesized for our review.

Results

Identified studies

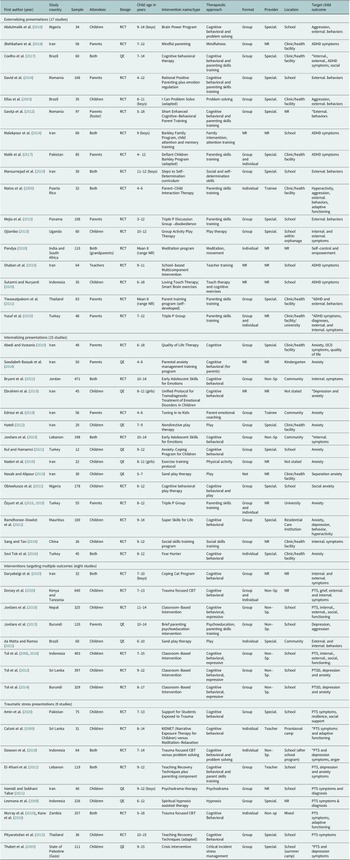

Search Strategy 1 identified 52 manuscripts from 49 unique intervention studies from LMICs (Figure 1). Details of the studies are outlined in Table 2. Search Strategy 2 resulted in synthesis of 53 reviews from the global literature: 5 Cochrane reviews (2 on interventions for internalizing symptoms, 2 for both internalizing and externalizing and 1 for trauma), 18 additional systematic reviews and meta-analyses on interventions for internalizing symptoms, 15 on interventions for externalizing symptoms, 7 on post-traumatic stress and 9 reviews on interventions targeting multiple outcomes or with transdiagnostic benefits (see Supplementary Material S3 for an overview of studies included). Search Strategy 3 identified 15 guidelines (see Supplementary Material S4), though many of these highlighted weak evidence or recommendations for specific interventions with children and adolescents, and aged 5–12 years in particular.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for individual studies identified from low- and middle-income countries (Strategy 1).

Table 2. Details of studies conducted in LMICs

Note: *no significant between group effects; ADHD, attention–deficit hyperactivity disorder; External., externalising; Internal., internalising; Non-Sp, nonspecialist; NR, not reported; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTS, post-traumatic stress; QE, quasi-experimental design; RCT, randomized controlled trial; Special., Specialist; Trainee, trainee in clinical psychology.

Findings across search strategies are synthesized according to categories of presenting emotional or behavioral difficulties below, and key findings are summarized in Box 1. Beyond specific evidence for these presentations, several guidelines provided general recommendations to pay attention to implementation considerations including: adaptation of interventions for age/language, cultural responsiveness, partnerships with other providers/sectors, training and supervision and responding to the needs of caregivers in addition to responding to caregiver mental health problems when indicated.

Box 1: Key findings from the review

Internalizing symptoms:

-

- CBT interventions show promise in reducing internalizing symptoms, particularly in older children and early adolescents.

-

- Play-based approaches have been used with younger children, but strong evidence is lacking.

-

- Group-based interventions have shown promising results, but there is no conclusive evidence finding differences between individual, group or family-based delivery.

-

- Training parents to deliver CBT or emotion coaching to young children may be effective, but further research is needed on optimal involvement of caregivers.

-

- Promising components may include problem-solving, psychoeducation, mindfulness, in-session exposure, social skills and cognitive strategies.

-

- There is limited evidence for nonspecialist approaches in LMICs.

Externalizing symptoms:

-

- Limited evidence exists for interventions targeting externalizing symptoms, and we found no evidence for nonspecialist approaches in LMICs and humanitarian settings.

-

- Parenting programs targeting behavioral management strategies show most promise

-

- Additional of relationship enhancement strategies may be beneficial.

-

- Group-based child-focused interventions (including play, CBT, problem solving) may be considered for children 9 and above, but require further study.

-

- Caregiver involvement is important, especially for younger children. with both caregivers involved where possible.

Traumatic stress symptoms:

-

- There have been few high quality studies for interventions targeting traumatic stress in young children in LMICs, especially delivered by nonspecialists.

-

- There are mixed findings regarding treatment content with some studies showing equivalent effects between different active interventions.

-

- Trauma-focused CBT approaches have the most evidence, both in group and individual formats.

-

- Involvement of caregivers is important.

-

- The impact of CBT interventions on other symptoms is not well understood.

Combined outcomes:

-

- There are few studies targeting a combination of outcomes delivered by nonspecialists in LMIC and these have shown mixed results.

-

- Global evidence is mixed for cross-diagnostic impacts of interventions.

-

- Group-based cognitive-behavioral interventions may be effective for children as young as 7 years but further research is needed to determine which interventions work best for different subgroups.

Key implementation considerations:

-

- Flexibility in intervention packages is important to address the diverse needs and developmental stages of children and families in these settings.

-

- Schools and kindergartens can serve as important entry points for intervention, but further research is needed on school-based delivery, and efforts should also reach out-of-school children.

-

- Further research is needed on training and supervision needs, as well as real-world implementation and quality assurance.

-

- Screening should encompass a broad range of emotional and behavioral challenges, considering cultural and contextual factors.

Interventions for internalizing symptoms

Evidence from LMIC studies

Fifteen unique studies (nine RCTs and six quasi-experimental (QEs)) examined effectiveness of interventions for internalizing symptoms. The studies varied in greatly in size and only two were conducted in conflict-affected settings (Jordan and Lebanon). The remaining 13 studies were conducted in LMICs, with 3 targeting children exposed to specific adversities: living in residential care institutions, child labor, exposed to child abuse. All studies required a diagnosis or a clinical score on a standardized measure, with many outreaching children in specialist services, and some doing broader screening including in schools. Five studies included children aged 6 and younger, one included children aged 7–9 years, and the remainder had age ranges between 8 and 14 years; one included only girls. Only 2 specified delivery by nonspecialists, and most used a group format with 6–16 sessions. Eight included children only (six group; two format not reported), three included parents and children (two group, one individual) and four worked with mothers only (two group, one combination and one format not reported).

Specific interventions included: variants of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for children (n = 7): teaching mothers to implement CBT techniques or emotional coaching with their children (n = 2); social skills training (n = 1); parenting interventions (n = 1); quality of life therapy (n = 1); physical activity only (n = 1); and play therapy (n = 2).

Thirteen of these studies reported a significant improvement in the treatment group versus the control group on at least one child-focused outcome; however, for two studies, this was only for specific subscales of measures. Of the 15 interventions, 6 showed promising effects and further information was extracted and presented below.

Two studies examined the EASE intervention among Syrian refugee adolescents in Jordan (n = 471) (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Malik, Aqel, Ghatasheh, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, van Ommeren and Akhtar2022) and Lebanon (n = 198) (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Brown, Kane, Taha, Steen, Ali, Elias, Meksassi, Aoun and Greene2023). The intervention consisted of seven 90-min group sessions for adolescents and three sessions for caregivers, delivered by nonspecialist providers provided with brief training and regular supervision. Content for adolescents included identifying emotions, relaxation, behavioral activation and problem solving, while caregivers discussed how to support their adolescent, self-care and positive parenting strategies. In Jordan, the intervention improved internalizing symptoms for adolescents and reduced psychological distress and inconsistent parenting for caregivers at a 3-month follow-up. No significant effects were found on other measures. In Lebanon, the trial was ended prematurely due to ongoing adversity and the COVID-19 pandemic, but findings showed equivalent changes in treatment and control groups.

Two other studies evaluated group-based specialist-delivered CBT interventions. In Mauritius, Ramdhonee-Dowlot et al. (Reference Ramdhonee-Dowlot, Essau and Balloo2021) evaluated Super Skills for Life for 9- to 14-year-olds in residential care (n = 100), finding significant improvements in anxiety, depression, conduct problems, hyperactivity and inhibitory control and emotion regulation, at both post-intervention and a 3-month follow-up. In Nigeria (n = 178), a group-based CBT play therapy reduced social anxiety and general anxiety in children aged 6–12 years with stutters at post-intervention and 4 months later (Obiweluozo et al., Reference Obiweluozo, Ede, Onwurah, Uzodinma, Dike and Ejiofor2021).

Two studies targeted child outcomes via parents. In Turkey (n = 55), the group-based Triple P program significantly reduced psychological and anxiety symptoms and improved functioning for 8- to 12-year-olds with anxiety disorders at post-intervention and 4 months after the intervention (Özyurt et al., Reference Özyurt, Gencer, Öztürk and Özbek2019). Edrissi et al. (Reference Edrissi, Havighurst, Aghebati, Habibi and Arani2019) conducted an RCT of the six group-session Tuning into Kids intervention with 56 mothers of children aged 4–6 years in Iran, focused on teaching emotion coaching to mothers. Child anxiety significantly reduced in the intervention group compared to the control group and was maintained after 6 months.

Evidence from global reviews

Several reviews reported on the benefit of CBT for childhood anxiety, with small to moderate effect sizes. James et al. (Reference James, Reardon, Soler, James and Creswell2020) conducted a Cochrane review of 87 studies trialing CBT for anxiety disorders with 5,964 children. Findings showed that CBT had a higher remission rate for anxiety diagnoses compared to waitlist or no treatment controls. However, there was limited evidence when comparing CBT to active controls or other treatments. The review was not able to determine differences between CBT and medication or CBT combined with medication due to a lack of relevant studies, nor the long-term effects of CBT, due to insufficient studies. Outcomes did not vary based on duration of treatment. Group-based interventions had stronger symptom outcomes reported by parents and children, but potential confounding factors were noted. The review also highlighted age-related measurement issues as a source of variation in outcomes across different age groups.

Strawn et al. (Reference Strawn, Lu, Peris, Levine and Walkup2021) provide an overview of more than 20 RCTs showing the benefit of CBT and outline that the approach has limited negative side effects. Luo and McAloon (Reference Luo and McAloon2021) report similar findings, concluding that CBT moderately reduces anxiety symptoms. Wergeland et al. (Reference Wergeland, Riise and Ost2021) note that CBT is effective in reducing internalizing disorders and symptoms for children and adolescents, and the outcomes are comparable with older populations. Generally, children experiencing higher scores at baseline experienced higher rates of change (Wergeland et al., Reference Wergeland, Riise and Ost2021). Similar benefits were found for digitally delivered programs (Strawn et al., Reference Strawn, Lu, Peris, Levine and Walkup2021). One review found that school-based programs appear to reduce anxiety symptoms in this age group but evidence is weak (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Davies, Hetrick, Palmer, Caro, López-López, Gunnell, Kidger, Thomas, French, Stockings, Campbell and Welton2019). A further review found that very small benefits for anxiety symptoms were maintained until 12 months in school-based programs (Hugh-Jones et al., Reference Hugh-Jones, Beckett, Tumelty and Mallikarjun2021).

CBT-based interventions for childhood anxiety typically include psychoeducation, relaxation techniques, cognitive restructuring and exposure tasks (Strawn et al., Reference Strawn, Lu, Peris, Levine and Walkup2021). Specific therapeutic processes within CBT have been identified as driving program effectiveness. Individual-, group- and family-based CBT have shown more benefits compared to control conditions (Sigurvinsdottir et al., Reference Sigurvinsdottir, Jensinudottir, Baldvinsdottir, Smarason and Skarphedinsson2020). Brief interventions involving social skills training and parent training have been effective in reducing anxiety (Stoll et al., Reference Stoll, Pina and Schleider2020). In-session exposure tasks have been found to improve anxiety levels, while relaxation techniques have shown less impact (Whiteside et al., Reference Whiteside, Sim, Morrow, Farah, Hilliker, Murad and Wang2020). Group psychoeducation has also demonstrated reductions in anxiety symptoms, although interventions vary widely (Baourda et al., Reference Baourda, Brouzos, Mavridis, Vassilopoulos, Vatkali and Boumpouli2021). Mindfulness-based interventions have shown a small to moderate effect on anxiety but lack sustained outcomes (Odgers et al., Reference Odgers, Dargue, Creswell, Jones and Hudson2020).

Parent-only CBT was effective in reducing anxiety, comparable to programs involving both children and parents. Parent-directed CBT may be more suitable for younger children, but dropout rates tend to be higher in parent-only programs (Yin et al., Reference Yin, Teng, Tong, Li, Fan, Zhou and Xie2021). Other reviews have shown that parental involvement is not necessarily beneficial in the treatment of anxiety (Cordier et al., Reference Cordier, Speyer, Mahoney, Arnesen, Mjelve and Nyborg2021; Peris et al., Reference Peris, Thamrin and Rozenman2021; Wergeland et al., Reference Wergeland, Riise and Ost2021).

In contrast, there is limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of interventions for depression in young children (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Ciharova, Miguel, Noma, Stikkelbroek, Weisz and Furukawa2021a,Reference Cuijpers, Pineda, Ng, Weisz, Munoz, Gentili, Quero and Karyotakib; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Li, Wu, Li, Qian, Jia, Wang, Qian and Xu2021). In a Cochrane review, the use of CBT, third-wave CBT and interpersonal therapy in preventing depression in children and adolescents was examined (Hetrick et al., Reference Hetrick, Cox, Witt, Bir and Merry2016). The review included 83 trials, with 53 involving targeted or indicated populations. Findings indicated a small positive effect on depression diagnosis, depression symptoms, general and social functioning, with evidence deemed of low to moderate quality.

Interventions for subthreshold depression have shown little effectiveness (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Pineda, Ng, Weisz, Munoz, Gentili, Quero and Karyotaki2021b). Only a small proportion of young people respond to current depression therapy models (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Ciharova, Miguel, Noma, Stikkelbroek, Weisz and Furukawa2021a). School-based programs have not demonstrated evidence for reducing depression symptoms (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Davies, Hetrick, Palmer, Caro, López-López, Gunnell, Kidger, Thomas, French, Stockings, Campbell and Welton2019). Network meta-analyses have shown that interpersonal psychotherapy and in-person CBT have better effects than control conditions, but the age range covered extends into adolescence (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Li, Wu, Li, Qian, Jia, Wang, Qian and Xu2021). Resilience-oriented programs focusing on cognitive, problem-solving and social skills resulted in improvements in depression symptoms in both targeted and universally delivered programs, which were maintained in the medium term (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Huang and Cui2020).

Technical guidelines

Technical guidelines reviewed generally underscored the lack of quality evidence for this age group, yet largely recommended group- or individual-based CBT for anxiety and depression with recommendations of family-therapy components to provide adjunctive benefits, in particular for more severe presentations (National Institute for Health Care and Clinical Excellence, 2019; Walter et al., Reference Walter, Bukstein, Abright, Keable, Ramtekkar, Ripperger-Suhler and Rockhill2020, Reference Walter, Abright, Bukstein, Diamond, Keable, Ripperger-Suhler and Rockhill2023).

Interventions for externalizing symptoms

Evidence from LMIC studies

Seventeen studies, including sixteen RCTs and one QE study with varying sample sizes, examined interventions for externalizing problems such as attention–deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms, aggression, oppositional defiant behavior, conduct problems and antisocial behavior. All studies required children to have a diagnosis, or score above a cut-off on a structured screening tool and most studies included children referred to specialist clinics. Two studies were conducted in Romania in 2019 when it was classified as a middle-income country, while the rest were in LMICs, with only one working with conflict-affected orphans with behavioral difficulties in Uganda. Seven studies included children with behavioral difficulties broadly, while 10 studies specifically focused on children with an ADHD diagnosis or clinical level of symptoms. Six studies included young children 6 years and younger, seven included children between 7 and 14 years and two included only 10- to 12-year-olds (two did not report age). Four studies only included boys. Eight interventions were conducted in schools, while seven were conducted in clinics (two did not report location).

Therapeutic approaches varied, including mindfulness/meditation (n = 2), parent skills training (n = 8), teacher training (n = 1), touch therapy (n = 1), play (n = 1), cognitive exercises (n = 2), problem solving (n = 2) and cognitive behavioral (n = 4). The length of each intervention varied greatly and ranged from a single session with two follow-up calls, to weekly sessions for 1 year. Within this range, most interventions were run between 3 and 10 weeks. Interventions involved children only (n = 5), child-caregiver dyads (n = 5) and caregivers only (n = 7). The majority (n = 12) delivered content in group or a combination of group and individual sessions. None reported delivery by nonspecialists.

Thirteen studies reported on a significant improvement in the treatment group on at least one outcome; five of these had sufficient detail and sample size to explore further. Only one study evaluated a child-focused program. Ojiambo (Reference Ojiambo2013) observed significant improvements in externalizing problems for displaced orphans aged 10–12 years living in Uganda and participating in group activity play therapy compared to a control group, with positive effects also seen for internalizing symptoms.

Two studies tested parenting interventions for parents of children with ADHD. Behbahani et al. (Reference Behbahani, Zargar, Assarian and Akbari2018) evaluated a mindful parenting group intervention with a sample of 56 parents of children aged 7–12 years in Iran. They found significant improvements in child symptoms, as well as parent distress and parent–child interactions. Malik et al. (Reference Malik, Rooney, Chronis-Tuscano and Tariq2017) trialed an adapted version of the Defiant Child intervention with 85 parents of children aged 4–12 years in Pakistan, consisting of both group and individual sessions. They found significant treatment effects for several indicators of disruptive behavior in the home, but not school.

Two studies tested parent skills training for parents of children with externalizing behavioral difficulties. David et al. (Reference David, David and Dobrean2014) conducted a trial of a 10-session enhanced Rational Positive Parenting intervention (delivered by specialist school counselors) including behavioral parenting strategies plus caregiver emotion regulation strategies with 106 caregivers in Romania. They found significantly reduced child externalizing behavior problems in both the standard behavioral parenting program and the enhanced program, compared to waitlist. In a sample of 106 parents in Panama, Mejia et al. (Reference Mejia, Calam and Sanders2015) found that a single session Triple P discussion group on the topic of disobedience led to significant improvements in problematic behaviors in children, sustained through 6-month follow-up.

Evidence from global reviews

Several reviews find that parenting support programs effectively reduce child behavior problems (O’Connor and Hayes, Reference O’Connor and Hayes2018; Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Gardner, Melendez-Torres, Van Aar, Hutchings, Schulz, Knerr and Overbeek2019a; Retuerto et al., Reference Retuerto, Ros Martinez de Lahidalga and Ibanez Lasurtegui2020; Thongseiratch et al., Reference Thongseiratch, Leijten and Melendez-Torres2020; McAloon and de la Poer Beresford, Reference McAloon and de la Poer Beresford2021; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Hunnicutt Hollenbaugh and Kelly2021; Riise et al., Reference Riise, Wergeland, Njardvik and Ost2021; Valero Aguayo et al., Reference Valero Aguayo, Rodríguez Bocanegra, Ferro García and Ascanio Velasco2021). These programs are often based on behavior management skills rooted in Operant Learning Theory and Social Learning Theory (Patterson, Reference Patterson1982; Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Gardner, Melendez-Torres, Van Aar, Hutchings, Schulz, Knerr and Overbeek2019a). Some effective programs primarily focus on teaching techniques to promote positive reinforcement (e.g., reward or praise), whereas others programs include techniques on nonviolent discipline (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Gardner, Melendez-Torres, Van Aar, Hutchings, Schulz, Knerr and Overbeek2019a). A meta-analysis was conducted on 156 studies to test whether parenting programmes consisting of the “golden couple” (relationship enhancement and behavior management) were more effective in reducing disruptive child behavior than programs that included only one component (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Gardner, Melendez-Torres, Van Aar, Hutchings, Schulz, Knerr and Overbeek2019a). Authors found that the “golden couple” was more beneficial for use in treatment programs but not preventive programs.

A network meta-analysis identified four active parenting program types (behavior management, behavior management with parental self-management, behavior management with psychoeducation and relationship enhancement), with focused interventions on behavior management alone showing the highest effectiveness (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Melendez‐Torres and Gardner2022). They conclude that there is a need for more targeted or tailored programs, or programs whose components are flexible and adaptable to the target population (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Melendez‐Torres, Gardner, Van Aar, Schulz and Overbeek2018b). The “Incredible Years” parenting program (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Gardner, Landau, Harris, Mann, Hutchings, Beecham, Bonin and Scott2018a; Reference Leijten, Gardner, Melendez-Torres, Weeland, Hutchings, Landau, McGilloway, Overbeek, van Aar and Menting2019b Gardner et al., Reference Gardner, Leijten, Harris, Mann, Hutchings, Beecham, Bonin, Berry, McGilloway and Gaspar2019) is an example of an effective manualized intervention that incorporates multiple strategies. It follows a collaborative group-based model that enables parents to identify their own skills and enables them to identify effective strategies to achieve their goals in their own family context. Overall, there is a strong rationale for including more than just behavior management techniques in parent and family support programs as it can effectively target multiple family characteristics that can contribute to the prevention of disruptive child behavior (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Gardner, Melendez-Torres, Van Aar, Hutchings, Schulz, Knerr and Overbeek2019a). However, there is also evidence that suggests “less is more” in parenting programs, as it provides parents with the opportunity to focus and master one technique (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Gardner, Melendez-Torres, Van Aar, Hutchings, Schulz, Knerr and Overbeek2019a).

Beyond parenting intervention, two reviews examined moderators of effectiveness in psychosocial programs for children and adolescents with conduct problems. McMahon et al. (Reference McMahon, Goulter and Frick2021) found that higher baseline symptoms, maternal depression, father engagement and individual program delivery (compared to group) were associated with larger positive effects. On the other hand, they found no evidence of moderation in either direction for child diagnosis, family risk level and intervention setting. Baumel et al. (Reference Baumel, Mathur, Pawar and Muench2021) similarly found that interventions for children with behavior problems within the clinical range had small to moderate effects (with no significant effect for interventions for children with symptoms below clinical levels) and individually delivered programs involving both the parent and child were most effective. Two school-based reviews did not report on factors that might have contributed to the effectiveness of these programs so little is known about what works in the school setting specifically (O’Connor and Hayes, Reference O’Connor and Hayes2018; Retuerto et al., Reference Retuerto, Ros Martinez de Lahidalga and Ibanez Lasurtegui2020).

Technical guidelines

The Helping Adolescents Thrive (HAT) guidelines conditionally recommend (based on very low certainty of evidence) that interventions be provided to adolescents with disruptive behavior, and could include training for parents based on social learning approaches, social-cognitive problem solving and interpersonal skills training for adolescents and joint caregiver-adolescent session based on social learning model (WHO, 2020). WHO’s mhGAP Intervention Guide (WHO, 2016) recommends providing psychoeducation, parent skills training, caregiver support, engagement with school, strengthening of social supports and behavioral interventions when available. The National Institute for Health Care and Clinical Excellence guidelines for antisocial and conduct problems in young people recommend group cognitive-behavioral and social problem solving interventions only for children aged 9 and above (National Institute for Health Care and Clinical Excellence, 2023). This guidance recommends parent-only or child-and-parent interventions based on social learning models for children aged 3–11 years and encourages involvement of both caregivers where possible.

Interventions for traumatic stress symptoms

Evidence from LMIC studies

Nine unique studies, including seven RCTs and two QE studies of varying sample sizes, examined interventions for traumatic stress outcomes for populations affected by natural disasters (n = 4), armed conflict and displacement (n = 3), a bombing (n = 1) and exposure to other traumatic events (n = 1). Four studies required a PTSD diagnosis as determined by clinical interview, while five utilized standardized self-report measures. The interventions tested were primarily CBT-based (n = 6), with other content including critical incident stress management, spiritual hypnosis and psychodrama. Interventions had varying session lengths and formats (n = 6 group, n = 3 individual) and five were conducted in school settings. Screening methods relied on standardized tools, and all but one study included both boys and girls. Interventions focused on children aged 5–18 years with two studies including children 6 years and younger. Only three interventions also included caregivers for at least one session.

Six out of the nine studies reported significant improvements in the treatment group compared to the control group for at least one outcome, including reductions in PTS symptoms. Two studies showed significant within-group improvements, but no difference between two active treatment conditions: trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) versus problem solving (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Joscelyne, Meijer, Steel, Silove and Bryant2018), and narrative exposure therapy versus meditation-relaxation (Catani et al., Reference Catani, Kohiladevy, Ruf, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2009). The three promising studies all evaluated interventions based on TF-CBT and found significant improvements in PTS and other outcomes: group-based intervention delivered by specialists in schools for children aged 7–13 years following floods in Pakistan (Amin et al., Reference Amin, Nadeem, Iqbal, Asadullah and Hussain2020); group-based Teaching Recovery Techniques intervention plus behavioral parenting sessions, delivered by teachers in schools for Syrian refugee children aged 9–12 years and their caregivers in Lebanon (El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Cartwright, Maalouf, Haar, Zehra, Çokamay-Yılmaz and Calam2021); and individual nonspecialist delivered TF-CBT for trauma-affected children aged 5–18 years in Zambia, and their caregivers (Kane et al., Reference Kane, Murray, Cohen, Dorsey, Skavenski van Wyk, Galloway Henderson, Imasiku, Mayeya and Bolton2016; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Hall, Dorsey, Ugueto, Puffer, Sim, Ismael, Bass, Akiba, Lucid, Harrison, Erikson and Bolton2018). Both nonspecialist interventions relied on brief trainings and regular supervision.

Evidence from global reviews

Recently published reviews emphasize the effectiveness of TF-CBT as the recommended treatment for PTSD in children and adolescents (Chipalo, Reference Chipalo2021; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Cipriani, Teng, Del Giovane, Zhang, Weisz, Li, Cuijpers, Liu and Barth2021; Yohannan et al., Reference Yohannan, Carlson and Volker2022). Cognitive processing therapy, behavioral therapy, individual TF-CBT and group TF-CBT were found to be effective compared to controls; however, there is a limited evidence base and need for further research with different populations. McWey (Reference McWey2022) reviewed interventions for traumatic stress (in children and adolescents) that focused on couple of family- and partner- based relational processes. The author found that so-called systemic interventions reduced post-traumatic stress symptoms in young people. A further review on art therapy for children and adolescents with mental health disorders found two relevant RCTs and authors suggest that this approach may be beneficial for young people with PTSD (Braito et al., Reference Braito, Rudd, Buyuktaskin, Ahmed, Glancy and Mulligan2022).

When examining moderators of treatment effectiveness, Yohannan et al. (Reference Yohannan, Carlson and Volker2022) found that moderators of the effect of CBT treatment included trauma type (children who had experienced physical abuse, single incident or traumatic grief had better outcomes) and gender (males benefitted more). Danzi and La Greca (Reference Danzi and La Greca2021) identified age (younger children), maternal depression and unhelpful beliefs as moderators leading to poorer treatment response. Group-based interventions were less effective than individual ones, and no differences were found based on provider or trauma type. Powell et al. (Reference Powell, Patel, Haley, Haines, Knocke, Chandler, Katz, Seifert, Ake, Amaya-Jackson and Aarons2020) highlighted issues with parenting engagement, including logistical challenges and past experiences with accessing care.

Technical guidelines

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinical Practice Parameter (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen2010) recommends that treatment of children with PTS symptoms should include education of the child and parents about PTSD, consultation with school personnel and TF psychotherapy including cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy and/or family therapy. Parents should be included in treatment where possible. The HAT guidelines similarly recommend individual TF-CBT for higher trauma exposure (WHO, 2020). International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies guidelines (Bisson et al., Reference Bisson, Berliner, Cloitre, Forbes, Jensen, Lewis, Monson, Olff, Pilling, Riggs, Roberts and Shapiro2019) recommend TF-CBT (both for caregiver/child dyads and child alone) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing for the treatment of children and adolescents with clinically relevant post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Interventions targeting multiple outcomes

Evidence from LMIC studies

Eight studies, consisting of seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and one QE study, examined interventions targeting multiple symptom presentations in conflict-affected settings (n = 5) and LMICs (n = 3). Interventions typically targeted broad age ranges, but only one worked with children 6 years and younger, and one worked only with boys. All studies utilized standardized screening measures to identify children; often screening took place in schools. The interventions, mostly based on CBT (n = 6), included group (n = 6), individual sessions (n = 1) and combination group/individual (n = 1), ranging from 2 to 20 sessions, with five conducted via schools. One intervention targeted parents only, and one targeted parent–child dyads, while the remainder focused on children only. Six interventions were delivered by nonspecialists. All eight studies reported significant improvements in the treatment group compared to the control group, but in some cases, these effects were specific to subgroups or study sites. All nonspecialist interventions utilized brief classroom-based trainings followed by practice and regular supervision.

Of the five studies showing promise, four were RCTs of the 15-group-session nonspecialist delivered classroom-based intervention in different conflict-affected contexts, with mixed results regarding reductions in emotional or behavioral problems. The intervention showed reductions in psychological difficulties and aggression for boys in Nepal but had no effects on PTSD, depression, anxiety or functioning (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe, Tol, Kohrt, Luitel, Macy and De Jong2010). In Indonesia, there was a reduction in PTSD symptoms for girls (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Komproe, Susanty, Jordans, Macy and De Jong2008), while in Sri Lanka, the intervention had an effect on conduct problems and PTSD and anxiety symptoms in boys (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Komproe, Jordans, Vallipuram, Sipsma, Sivayokan, Macy and de Jong2012). In Burundi, no overall effects were found, but there were effects on depression symptoms and functional impairment for children in larger households (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Komproe, Jordans, Ndayisaba, Ntamutumba, Sipsma, Smallegange, Macy and de Jong2014).

Dorsey et al. (Reference Dorsey, Lucid, Martin, King, O’Donnell, Murray, Wasonga, Itemba, Cohen and Manongi2020) tested a 12-week culturally adapted group-based TF-CBT focusing on parental death with 634 orphaned children aged 7–13 years in Kenya and Tanzania. The intervention consisted of 12 group sessions, plus 3–4 individual sessions, delivered by a lay counselor trained over 4.5 days and provided with weekly supervision by local supervisors who in turn received weekly master supervision from international study leads. Counselors showed high levels of competence and fidelity. Children were included if they screened positive on a measure of post-traumatic stress, or a measure of prolonged grief. TF-CBT was effective in reducing PTS symptoms in three of four sites, and this was retained at the 12-month follow-up in two sites, with similar patterns for outcomes of prolonged grief, and internalizing symptoms.

Evidence from global reviews

Some reviews examined interventions for cross-diagnostic benefits. In the parenting-directed programs, we found four reviews focused on establishing the impact of programs for parents of children with disruptive behaviors on internalizing problems. Phillips and Mychailyszyn (Reference Phillips and Mychailyszyn2021) found that PCIT reduced anxiety compared to control condition. A review of the effect of parenting interventions for child disruptive behavior on internalizing symptoms identified 12 studies of the Incredible Years, Triple-P and Tuning into Kids reporting on both outcomes. All but one study reported positive impact on externalizing behaviors and over half also reported significant improvement in internalizing symptoms (Zarakoviti et al., Reference Zarakoviti, Shafran, Papadimitriou and Bennett2021). Similarly, one review looked at parenting programs for conduct disorder and found small post-intervention effects on parent-reported emotional problems, but that these were not sustained. There were no specific individual program elements that predicted larger improvements, but behavior management and relationship enhancement together predicted larger effects (Kjøbli et al., Reference Kjøbli, Melendez‐Torres, Gardner, Backhaus, Linnerud and Leijten2022). Another review found that Triple P had a positive impact on social competence, emotional and behavioral problems, as well as a range of parenting-related outcomes (Li et al., Reference Li, Peng and Li2021).

Many of the other reviews on interventions that might reduce both internalizing and externalizing interventions did not identify sufficient studies or were inconclusive. One review looked to describe the evidence for the use of modular school-based mental health interventions based on a common-elements approach and was only able to identify programs for internalizing problems, but not externalizing (Kininger et al., Reference Kininger, O’Dell and Schultz2018). A review of school-based interventions showed that there was some evidence to suggest that selective prevention for either anxiety or depression was more effective than working across diagnostic categories, but authors were not able to draw firm conclusions (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Davies, Hetrick, Palmer, Caro, López-López, Gunnell, Kidger, Thomas, French, Stockings, Campbell and Welton2019). A review of an attachment-based intervention for children with existing symptoms or diagnoses was not able to establish the effectiveness of the program; however, the authors concluded that it may be effective for children with more than one condition (Money et al., Reference Money, Wilde and Dawson2021). One review that specifically looked at the effects of CBT on PTSD, depression and anxiety in child refugees found that most studies (including but not isolated to RCTs) reported positive results (Lawton and Spencer, Reference Lawton and Spencer2021). However, another review of interventions for refugees to target depression and PTSD was not able to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of interventions for refugees under 18 years due to the lack of evidence (Kip et al., Reference Kip, Priebe, Holling and Morina2020).

Technical guidelines

No guidelines were identified specifically for transdiagnostic interventions designed to address a range of symptoms. However, UNICEF’s review of evidence and practice (UNICEF, 2020) identifies several promising approaches to reduce general emotional distress and highlights the promise of Common Elements Treatment Approach and the Youth Readiness Intervention – both of which are transdiagnostic, components/common-elements approaches with adaptation of treatment strategies to fit new contexts and problems.

Discussion

In this review, we synthesized the findings of 52 intervention studies in LMICs (including humanitarian settings), 53 global systematic reviews and meta-analyses and 15 technical guidelines to identify the best evidence and practice for addressing emotional and behavioral difficulties in 5–12 year-old children. Overall, there is limited high-quality evidence to draw from this age group; however, some promising intervention approaches were identified for children experiencing externalizing and internalizing symptoms, traumatic stress and a combination of difficulties. Several effective interventions utilize cognitive-behavioral techniques for children in either group or individual format and/or target caregiver skills training, although the findings are mixed. Most evaluated interventions used specialists as delivery agents, and consist of a large number of sessions, which poses challenges for scale-up. There is a pertinent need for additional research to identify the active ingredients and optimal implementation strategies of interventions for this age group, in line with broader research priorities for global mental health research in general (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Le, Harrison, Galappatti, Annan, Baingana, Betancourt, Bizouerne, Eaton and Engels2023). Furthermore, there is a need to better understand the differential intervention impacts for boys and girls. Here, we outline some recommendations that can be drawn from our review to inform further research and development.

Developmental considerations

Our review supports previous studies (e.g., Yu et al., Reference Yu, Perera, Sharma, Ipince, Bakrania, Shokraneh, Sepulveda and Anthony2023), identifying comparatively more interventions for the upper ages in this bracket and limited evidence of what works for younger children. Several interventions targeted children aged from approximately 9–10 years old upward into adolescence. In addition, several of the reviews from HICs indicated a gap in effective interventions for the younger age bracket. As child development is occurring rapidly during this period, and can vary in different contexts given environmental conditions, a developmental approach with careful consideration of strategies and delivery methods for different ages and stages of development will be needed (Kågström et al., Reference Kågström, Juríková and Guerrero2023).

Transdiagnostic, tailored approaches

Across all categories of symptom presentations, interventions conducted in LMICs utilized CBT techniques, parent skills training and problem-solving, and these strategies had most support in global literature. The majority of studies in LMICs focused on specific problems (e.g., anxiety, ADHD), with fewer addressing a combination of presenting symptoms (e.g., internalizing and externalizing symptoms together). Interventions focusing on specific problems increase complexity for assessment and diagnostic procedures and create a burden for training providers on multiple intervention packages.

To meet the need for effective transdiagnostic psychological interventions that address the complex nature of diverse presenting problems in children, several promising examples of modular, adaptable nonspecialist interventions that can be tailored to meet the specific needs of individual children are emerging in LMICs. For example, the Common Elements Treatment Approach shows potential as a modular approach that can be provided by supervised nonspecialists; however, to date, there have been no controlled trials of this intervention for younger children (only pre-post studies) and the necessity of high quality training and supervision on identifying primary presenting problems and sequencing of intervention components has been noted (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Hall, Dorsey, Ugueto, Puffer, Sim, Ismael, Bass, Akiba, Lucid, Harrison, Erikson and Bolton2018; Bosqui et al., Reference Bosqui, McEwen, Chehade, Moghames, Skavenski, Murray, Karam, Weierstall-Pust and Pluess2023). Similarly, several modular whole-family interventions have been developed, with early indications of feasible delivery by nonspecialists (Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Friis Healy, Green, M Giusto, N Kaiser, Patel and Ayuku2020; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Yousef, Bleile, Mansour, Barrett, Ghatasheh, Puffer, Mansour, Hayef, Kurdi, Ali, Tol, El-Khani, Calam, Abu Hassan and Jordans2024). However, no RCT results are available to date, and studies have only included older children or adolescents.

The Modular Approach to Therapy for Children is a flexible and transdiagnostic treatment approach that utilizes 33 components from evidence-based treatments, with clinicians selecting and ordering components based on decision-making trees (Chorpita and Weisz, Reference Chorpita and Weisz2009). While studies with therapists in the USA have found positive results of this approach when therapists were provided weekly individual consultation with MATCH experts (e.g., Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Chorpita, Palinkas, Schoenwald, Miranda, Bearman, Daleiden, Ugueto, Ho, Martin, Gray, Alleyne, Langer, Southam-Gerow and Gibbons2012; Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Daleiden, Park, Ward, Levy, Cromley and Krull2017), later studies indicated that when MATCH was implemented under more ‘real-world’ conditions involving group consultation, without weekly supervision from MATCH experts, the impacts were not significantly better than standard practice (Merry et al., Reference Merry, Hopkins, Lucassen, Stasiak, Weisz, Frampton, Bearman, Ugueto, Herren, Cribb-Su’a, Kingi-Ulave, Loy, Hartdegen and Crengle2020; Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Bearman, Ugueto, Herren, Evans, Cheron and Jensen-Doss2020). A simplified transdiagnostic intervention called FIRST, based on five core principles (Feeling Calm, Increasing Motivation, Repairing Thoughts, Solving Problems and Trying the Opposite), has shown promise in children as young as seven, but requires further evaluation in RCTs and in diverse settings (Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Bearman, Santucci and Jensen-Doss2017; Cho et al., Reference Cho, Bearman, Woo, Weisz and Hawley2021). When delivering these approaches via nonspecialists, the challenge will lie in decision-making regarding component selection and sequencing, which is challenging even among professionals (Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Fitzpatrick, Venturo‐Conerly and Cho2021). Further research is needed into how to best support nonspecialists to do this, without reliance on intensive training and supervision models that may not be feasible in under-resourced settings.

Delivery agent

In LMICs and humanitarian settings, there are substantial barriers to ensuring access to mental health specialists for children. It is therefore crucial to develop feasible, scalable interventions that are based on evidence-based techniques and can be implemented by trained and supervised nonspecialists. While most intervention evaluations identified in LMICs were delivered by specialists, our review found promising examples of interventions successfully delivered by nonspecialists, including teachers. In our review of the global literature, there was some indication that specialist providers were more effective in school settings (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Davies, Hetrick, Palmer, Caro, López-López, Gunnell, Kidger, Thomas, French, Stockings, Campbell and Welton2019), but there were very few reviews that adequately identify optimal delivery agents. Beyond developing effective interventions, it is essential to determine the most strategic entry points and platforms for their delivery to enhance the overall effectiveness and impact.

It is important that guidance on the recruitment, training and supportive supervision of nonspecialist workers accompanies an intervention package, and that lessons on these issues are applied from adult mental health and related child health fields (Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hunt and Rotheram-Borus2018). We found limited data to support particular training and supervision models; however, brief focused training (e.g., 2 weeks) followed by observed practice and ongoing supervision and support were common in LMIC studies with nonspecialist providers. Developing models of training and supervision that do not rely on continuous support from intervention developers or international teams is important for scalability and sustainability. For example, in two studies of the EASE intervention, a Train the Trainer was provided for local trainers, who then trained and supervised facilitators, and themselves received regular remote consultation as needed. Experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic indicate that remote supervision is a feasible alternative to face-to-face sessions, which may be considered where logistical barriers exist (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Ostinelli, Macdonald and Cipriani2020; Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Ely, Garcia and Bowden2021; Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, Guidry, Picou, Adenuga and Davis2021; Nicholas et al., Reference Nicholas, Bell, Thompson, Valentine, Simsir, Sheppard and Adams2021). The UNICEF-WHO EQUIP tools may be an effective way to train, assess and monitor the needed competencies in facilitators, given recent research indicating the promise of competency-focused trainings (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Steen, Koppenol-Gonzalez, El Masri, Coetzee, Chamate and Kohrt2022). As professional development opportunities relevant to working with this age group are currently very limited, investment is needed into implementation science research to elucidate optimal methods for training, supervising, supporting and retaining a child mental health workforce that can deliver mental health interventions with quality at scale.

Delivery format

There were examples of effective group and individual format interventions in LMICs, and there were mixed recommendations regarding optimal format in global guidelines. While group-based interventions may offer lower costs and social benefits, individual delivery provides flexibility and adaptability, particularly in addressing parental and family dynamics influencing child mental health. The Cochrane review on CBT for childhood anxiety found that group delivery was not more effective in reducing anxiety diagnoses, but that parents and children enrolled in groups reported lower levels of symptoms (James et al., Reference James, Reardon, Soler, James and Creswell2020). Other reviews that compared group and individual formats found that both were effective (Sigurvinsdottir et al., Reference Sigurvinsdottir, Jensinudottir, Baldvinsdottir, Smarason and Skarphedinsson2020) and that group-based CBT is more effective than individually delivered (Luo and McAloon, Reference Luo and McAloon2021); however, these reviews included adolescent samples. On the other hand, for children with externalizing behaviors, reviews indicate that individual delivery of programs may be more effective (e.g., Baumel et al., Reference Baumel, Mathur, Pawar and Muench2021; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Goulter and Frick2021). In order to provide the tailored transdiagnostic approach outlined above, individual delivery format may be more feasible.

Caregiver involvement

Findings suggest that programs should include elements directed at both children and caregivers, depending on the child’s needs. For externalizing problems, parent-directed support and improving the parent–child relationship are recognized as beneficial (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Melendez‐Torres, Gardner, Van Aar, Schulz and Overbeek2018b). However, other reviews indicate that parental involvement is not necessarily essential in the treatment of anxiety (Cordier et al., Reference Cordier, Speyer, Mahoney, Arnesen, Mjelve and Nyborg2021; Peris et al., Reference Peris, Thamrin and Rozenman2021; Wergeland et al., Reference Wergeland, Riise and Ost2021). Children may also benefit from learning strategies independently from their families to address external sources of anxiety (e.g., at school) (Cordier et al., Reference Cordier, Speyer, Mahoney, Arnesen, Mjelve and Nyborg2021).

Caregivers in settings characterised by high adversity often experience heightened distress, impacting their ability to provide responsive parenting. In this way, caregiver distress can be a significant mediator of the impact of adversity on parenting, and therefore on child mental health outcomes (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Edwards, Creamer, O’Donnell, Forbes, Felmingham, Silove, Steel, Nikerson, McFarlane, Van Hoff and Hadzi-Pavlovic2018; Sim et al., Reference Sim, Bowes and Gardner2018). Interventions that combine parenting skills with caregiver well-being have shown promise in improving caregiver and child mental health outcomes (e.g., Miller et al., Reference Miller, Chen, Koppenol‐Gonzalez, Bakolis, Arnous, Tossyeh, El Hassan, Saleh, Saade and Nahas2023). Therefore, with this age group, it is likely to be beneficial to involve caregivers in interventions with the aim to promote support to the child, ensure their own well-being and build positive family dynamics.

Outreach and screening

In LMIC studies, outreach and screening were typically conducted specifically for the research study, often in clinical settings, and often using clinician diagnosis. To implement transdiagnostic interventions in diverse community settings, it will be crucial to develop a developmentally- and gender-appropriate tool for nonspecialist teams to identify both boys and girls in need and integrate detection and screening into existing services. Referral pathways to specialist services should also be established. The ReachNow tool (van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Hegazi, Ghazal, Hamayel, Barrett, Kohrt and Jordans2023) has shown promise in accurately identifying and referring children and adolescents to MHPSS services, and could be adapted for this purpose.

Limitations

In order to draw recommendations for designing new interventions, we took a pragmatic approach to analyzing available literature and did not aim to systematically capture all global evidence on interventions for this age range, nor conduct meta-analyses to conclusively determine effectiveness of different intervention strategies. It is possible that despite our efforts to include pertinent research, some important studies or reviews may have been omitted. In addition, parts of our search were limited to studies published in English due to resource constraints.

Conclusion

Middle childhood is a crucial period for social and emotional development, yet, evidence on effective psychological treatments for children that need them is lacking, particularly for children living in LMICs, humanitarian emergencies and contexts of adversity. Interventions to improve child mental health outcomes should be grounded in the strongest available evidence, while being responsive and adaptable to varying contexts. Our findings indicate the potential promise of transdiagnostic interventions delivered by nonspecialist providers to both children and caregivers, with utilization of cognitive behavioral treatment components. Future efforts should include the investigation of both the impact and implementation of interventions delivered in these settings, with consideration of differential needs and impacts based on gender and developmental stages.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.57.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.57.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the expert support and guidance on this evidence review from Koen Servants, May Aoun, Eman Gaber, Marcio Gagliato, Mark Jordans, Phiona Koyet, Mahmuda, Sara Pearce, Eve Puffer, Marija Raleva, Godfrey Siu, Paneth Sok, John Weisz and Katherine Venturo-Connerly. This review was conducted under the UNICEF and WHO Joint Program on Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing and Development of Children and Adolescents, and the authors thank both organizations for their support for this initiative.

Author contribution

The design, conduct and interpretation of this evidence review was informed and guided by all authors. Searches, screening of sources, data extraction, synthesis and drafting of the manuscript was conducted jointly by F.L.B., C.L. and S.S. All authors provided critical review of the final manuscript. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Financial support

This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and supported by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Grant number: 81268110.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

This study did not involve human participants, tissue or data.