Introduction

The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was diverse and had impacted physical, psychological, economic, and social contexts globally (Álvarez-Iglesias et al., Reference Álvarez-Iglesias, Garman and Lund2021; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Feng, Liu, Targher, Byrne and Zheng2021). Some populations were at higher risk of facing those impacts. For instance, healthcare workers (HCWs) were more vulnerable to contracting the infection than others due to the nature of their job responsibilities. That posed a significant threat not only on their health and wellbeing, but that of their co-workers, as well as the risk on their family members (Chou et al., Reference Chou, Dana, Buckley, Selph, Fu and Totten2020). The International Council of Nurses (ICN) reported deaths of many hundreds of nurses from COVID-19 worldwide. Therefore, working with patients from a high risk of infection areas could lead to mental health problems, including stress, anxiety, and depression (ICN, 2020). Studies demonstrated that the psychological wellbeing of HCWs had been considerably impacted due to their additional efforts to manage the high volume of COVID-19 patients during the pandemic (Chew et al., Reference Chew, Lee, Tan, Jing, Goh, Ngiam, Yeo, Ahmad, Ahmed Khan, Napolean Shanmugam, Sharma, Komalkumar, Meenakshi, Shah, Patel, Chan, Sunny, Chandra, Ong, Paliwal, Wong, Sagayanathan, Chen, Ying NG, Teoh, Tsivgoulis, Ho, Ho and Sharma2020; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Ma, Chen, Yang, Wang, Li, Yao, Bai, Cai, Xiang Yang, Hu, Zhang, Wang, Ma and Liu2020; Sirois and Owens, Reference Sirois and Owens2020). Such additional stress of the pandemic on their usual work-related stress was often considered part of the routine responsibilities. Importantly, during the pandemic many HCWs were required to be redeployed to work in settings outside of their clinical expertise/specialty. They had to work extra shifts or longer hours (Shechter et al., Reference Shechter, Diaz, Moise, Anstey, Ye, Agarwal, Birk, Brodie, Cannone, Chang, Claassen, Cornelius, Derby, Dong, Givens, Hochman, Homma, Kronish, Lee, Manzano, Mayer, Mcmurry, Moitra, Pham, Rabbani, Rivera, Schwartz, Schwartz, Shapiro, Shaw, Sullivan, Vose, Wasson, Edmondson and Abdalla2020), often with lack of resources, inadequate protection, and amidst high risk of infection (Alizadeh et al., Reference Alizadeh, Khankeh, Barati, Ahmadi, Hadian and Azizi2020). If the existing stress and COVID-19-related psychological distress were sustained, those could have impacted health and wellbeing of HCWs (Shechter et al., Reference Shechter, Diaz, Moise, Anstey, Ye, Agarwal, Birk, Brodie, Cannone, Chang, Claassen, Cornelius, Derby, Dong, Givens, Hochman, Homma, Kronish, Lee, Manzano, Mayer, Mcmurry, Moitra, Pham, Rabbani, Rivera, Schwartz, Schwartz, Shapiro, Shaw, Sullivan, Vose, Wasson, Edmondson and Abdalla2020), potentially leading to many short-and long-term mental health consequences. Some of the documented adverse events in healthcare settings included suicide, substance abuse, intention to quit their job, reduced provision of quality of care to patients following cognitive impairment and work-related stress, and being irritable with colleagues (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Graham, Potts, Candy, Richards and Ramirez2007; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Liu, Fang, Fan, Fuller, Guan, Yao, Kong, Lu and Litvak2008; Dall'Ora et al., Reference Dall'Ora, Griffiths, Ball, Simon and Aiken2015; Adler et al., Reference Adler, Adler and Grant-Kels2017). Therefore, it was imperative to understand the factors contributing to the risk of developing psychological distress during the pandemic, which could be considered while formulating policies in healthcare settings to reflect on better interventions for that critical workforce.

The impact of COVID-19 varied across the globe, so were the subsequent responses at a country level due to wide variations in health systems delivery. Psychological distress among HCWs was documented in earlier studies that showed very high and exaggerated impact during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to usual, ordinary circumstances and the general population (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Ma, Wang, Cai, Hu, Wei, Wu, Du, Chen, Li, Tan, Kang, Yao, Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu and Hu2020; Robles et al., Reference Robles, Rodriguez, Vega-Ramirez, Alvarez-Icaza, Madrigal, Durand, Morales-Chaine, Astudillo, Real-Ramirez, Medina-Mora, Becerra, Escamilla, Alcocer-Castillejos, Ascencio, Diaz, Gonzalez, Barron-Velazquez, Fresan, Rodriguez-Bores, Quijada-Gaytan, Zabicky, Tejadilla-Orozco, Gonzalez-Olvera and Reyes-Teran2020). However, most of those studies were country-specific, recruiting individuals from a single country. Since the impact of COVID-19 varied across the globe, subsequent responses from health authorities also varied due to wider variations in health systems, quality of clinical care, and health systems delivery mechanisms across countries. While in some countries, healthcare resources were not overwhelmed during the pandemic, in others, they were over-burdened (Dobson et al., Reference Dobson, Malpas, Burrell, Gurvich, Chen, Kulkarni and Winton-Brown2021). A thorough understanding of the psychological burden among HCWs was vital during that critical juncture of the pandemic (Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Shrestha, Baniya, Lamichhane, Shahi, Gurung, Tandan, Ghimire and Budhathoki2021). Hence, it was justified to examine the psychological impact of the pandemic on HCWs across multiple countries. Our previous global study showed that doctors had higher psychological distress but lower levels of fear, whereas nurses had high resilient coping during the COVID-19 pandemic (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Islam, Tungpunkom, Sultana, Alif, Banik, Salehin, Joseph, Lam, Watts, Khan, Ghozy, Chair, Chien, Schonfeldt-Lecuona, El-Khazragy, Mahmud, Al Mawali, Al Maskari, Alharbi, Hamza, Keblawi, Hammoud, Elaidy, Susanto, Bahar Moni, Alqurashi, Ali, Wazib, Sanluang, Elsori, Yasmin, Taufik, Al Kloub, Ruiz, Elsayed, Eltewacy, Al Laham, Oli, Abdelnaby, Dweik, Thongyu, Almustanyir, Rahman, Nitayawan, Al-Madhoun, Inthong, Alharbi, Bahar, Ginting and Cross2021a). However, factors associated with such psychological distress, fear, and coping among HCWs were not examined in that study (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Islam, Tungpunkom, Sultana, Alif, Banik, Salehin, Joseph, Lam, Watts, Khan, Ghozy, Chair, Chien, Schonfeldt-Lecuona, El-Khazragy, Mahmud, Al Mawali, Al Maskari, Alharbi, Hamza, Keblawi, Hammoud, Elaidy, Susanto, Bahar Moni, Alqurashi, Ali, Wazib, Sanluang, Elsori, Yasmin, Taufik, Al Kloub, Ruiz, Elsayed, Eltewacy, Al Laham, Oli, Abdelnaby, Dweik, Thongyu, Almustanyir, Rahman, Nitayawan, Al-Madhoun, Inthong, Alharbi, Bahar, Ginting and Cross2021a). Therefore, we aimed to identify the predictors of psychological distress, fear, and coping among HCWs across multi-country settings.

Methods

Study design and population

This cross-sectional online survey included data of self-identified HCWs from 14 countries (12 from Asia and two from Africa), including China (Hong Kong), Egypt, Indonesia, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Nepal, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which was extracted from the global study led by the last author (MAR) (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Islam, Tungpunkom, Sultana, Alif, Banik, Salehin, Joseph, Lam, Watts, Khan, Ghozy, Chair, Chien, Schonfeldt-Lecuona, El-Khazragy, Mahmud, Al Mawali, Al Maskari, Alharbi, Hamza, Keblawi, Hammoud, Elaidy, Susanto, Bahar Moni, Alqurashi, Ali, Wazib, Sanluang, Elsori, Yasmin, Taufik, Al Kloub, Ruiz, Elsayed, Eltewacy, Al Laham, Oli, Abdelnaby, Dweik, Thongyu, Almustanyir, Rahman, Nitayawan, Al-Madhoun, Inthong, Alharbi, Bahar, Ginting and Cross2021a).

Study population and sampling

HCWs who have completed the online questionnaire in any of the proposed languages (English/Arabic/Thai/Nepali) from those selected countries were included in this analysis. First, an affirmative response in the survey determined their identities as HCWs: ‘Do you identify yourself as a health care worker?’ Then the requested responses were ‘doctors’, or, ‘nurses’, or ‘other health care workers’.

Sampling and data collection

Our previous study detailed sample size calculation and data collection procedures (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Islam, Tungpunkom, Sultana, Alif, Banik, Salehin, Joseph, Lam, Watts, Khan, Ghozy, Chair, Chien, Schonfeldt-Lecuona, El-Khazragy, Mahmud, Al Mawali, Al Maskari, Alharbi, Hamza, Keblawi, Hammoud, Elaidy, Susanto, Bahar Moni, Alqurashi, Ali, Wazib, Sanluang, Elsori, Yasmin, Taufik, Al Kloub, Ruiz, Elsayed, Eltewacy, Al Laham, Oli, Abdelnaby, Dweik, Thongyu, Almustanyir, Rahman, Nitayawan, Al-Madhoun, Inthong, Alharbi, Bahar, Ginting and Cross2021a). Data were collected using an online questionnaire, which was distributed to the target population through Google form. The timeframe was November 2020 to January 2021. All responses were voluntary and anonymous; no incentives were offered to complete the questionnaire.

Study tool

The study questionnaire was translated to all of the aforementioned languages. The responses were translated back to English again under the supervision of local team leaders of each country, where responses were obtained and recorded for analyses in the current study. The study tools were described in prior published studies (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hoque, Alif, Salehin, Islam, Banik, Sharif, Nazim, Sultana and Cross2020, Reference Rahman, Islam, Tungpunkom, Sultana, Alif, Banik, Salehin, Joseph, Lam, Watts, Khan, Ghozy, Chair, Chien, Schonfeldt-Lecuona, El-Khazragy, Mahmud, Al Mawali, Al Maskari, Alharbi, Hamza, Keblawi, Hammoud, Elaidy, Susanto, Bahar Moni, Alqurashi, Ali, Wazib, Sanluang, Elsori, Yasmin, Taufik, Al Kloub, Ruiz, Elsayed, Eltewacy, Al Laham, Oli, Abdelnaby, Dweik, Thongyu, Almustanyir, Rahman, Nitayawan, Al-Madhoun, Inthong, Alharbi, Bahar, Ginting and Cross2021a, Reference Rahman, Rahman, Wazib, Arafat, Chowdhury, Uddin, Rahman, Bahar Moni, Alif, Sultana, Salehin, Islam, Cross and Bahar2021b; Bahar Moni et al., Reference Bahar Moni, Abdullah, Bin Abdullah, Kabir, Alif, Sultana, Salehin, Islam, Cross and Rahman2021; Chair et al., Reference Chair, Chien, Liu, Lam, Cross, Banik and Rahman2021), and their reliability was also assessed (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Salehin, Islam, Alif, Sultana, Sharif, Hoque, Nazim and Cross2021c). The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K-10), the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S), and the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) were used to assess psychological distress, fear, and coping of HCWs, respectively (Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Kessler, Slade and Andrews2003; Sinclair and Wallston, Reference Sinclair and Wallston2004; Ahorsu et al., Reference Ahorsu, Lin, Imani, Saffari, Griffiths and Pakpour2020). Based on the scoring in each tool, psychological distress was categorized into low (10–15) and moderate-to-very high (16–50), fear into low (7–21) and high (22–35), and coping into low (4–13) and medium-to-high (14–20).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using R software version 4.1.1. Means and standard deviations (±s.d.) were reported for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Both univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to assess factors associated with fear, distress, and coping strategies. Potential confounders were adjusted in the multivariate analyses. A p value < 0.05 was used as a cut-off for statistical significance. The findings were presented as odds ratios (ORs), adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Furthermore, country-wise analyses were conducted to compare the outcomes between participant countries. All the countries were organized according to severity, starting with countries with the lowest prevalence rates of medium-to-high levels of psychological distress, high levels of fear, and medium-to-very high levels of coping.

Results

Characteristics of HCWs

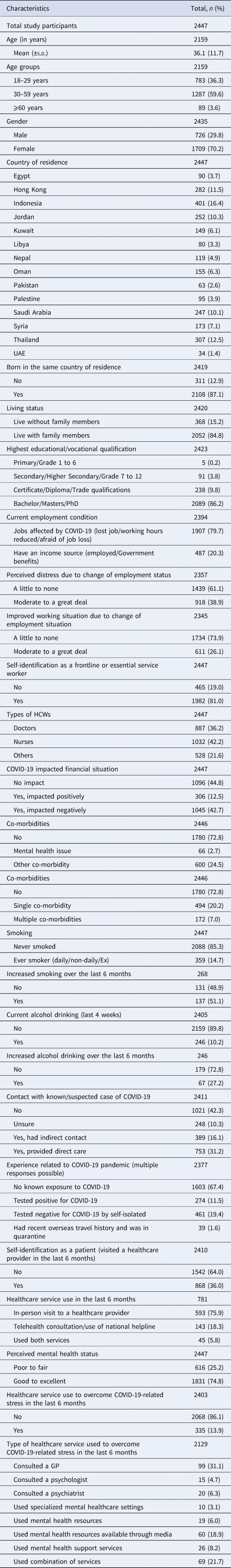

A total of 2447 HCWs were included in this study; 887 (36.2%) were doctors, 1032 (42.2%) were nurses, and 528 (21.6%) were others. The mean (±s.d.) age was 36.1 (±11.7) years, and the majority (70.2%) were females. Most participants were from Indonesia (16.4%), Thailand (12.5%), Hong Kong (11.5%), Jordan (10.3%), and Saudi Arabia (10.1%). Most of them (81%) self-identified as frontline/essential service workers. Most of the HCWs mentioned that their jobs were impacted by COVID-19 (79.7%); however, only 38.9% perceived moderate to great distress. Most participants said that they had no comorbidities (72.8%), were never smoked (85.3%), and did not drink alcohol within the past 4 weeks before data collection (89.8%). Direct contact with suspected/known COVID-19 cases was reported by 753 HCWs (31.2%), and 274 (11.5%) HCWs tested positive for COVID-19. A third of the HCWs (36%) visited a healthcare provider within the last 6 months, and one in 10 participants (13.9%) used healthcare services to address COVID-19-related stress. The detailed characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population

Levels of psychological distress, fear of COVID-19, and resilient coping

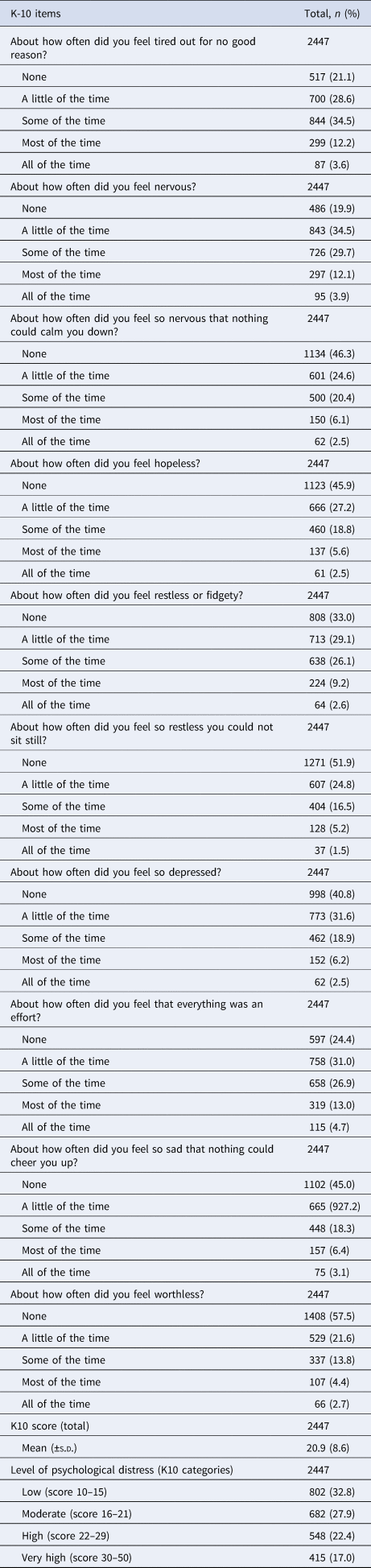

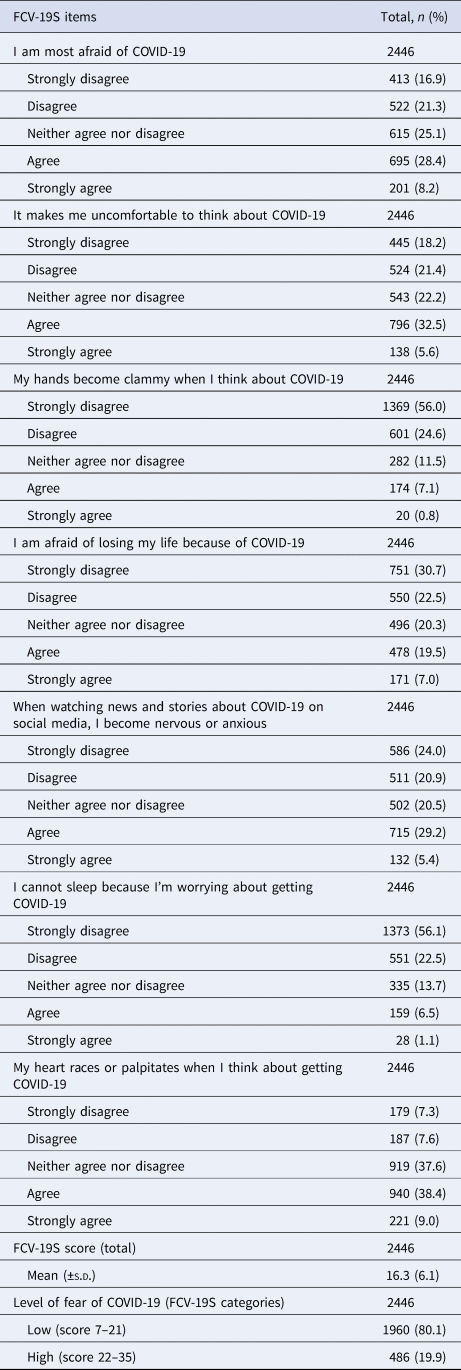

Regarding the levels of psychological distress, the mean K-10 score was 20.9 (± 8.6). The prevalence of low, moderate, high, and very high levels of psychological distress was 32.8, 27.9, 22.4, and 17.0%, respectively. The different domains of the K-10 score are presented in Table 2. Regarding the levels of fear, the mean FCV-19S score was 16.3 (± 6.1). The prevalence of low and high levels of fear of COVID-19 was 80.1% and 19.9%, respectively. The different domains of the FCV-19S score are presented in Table 3. The mean BRCS score was 14.2 (± 2.9), while the prevalence of low, moderate, and high resilient coping was 37, 47, and 16.1%, respectively. The different domains of the BRCS score are presented in Table 4.

Table 2. Level of psychological distress among the study participants

Table 3. Level of fear of COVID-19 among the study participants

Table 4. Coping during COVID-19 pandemic among the study participants

Predictors of psychological distress, fear, and coping

In the adjusted model, moderate to very-high psychological distress was associated with being, living with family members, perceived moderate to a great deal of distress, having comorbid conditions other than mental health issues, history of smoking, increased alcohol consumption within the last 6 months, unsure and indirect contact with known/suspected cases of COVID-19, self-identification as a patient (in addition to being a HCW), having high levels of fear related to COVID-19, and using healthcare services to overcome COVID-19-related stress. Conversely, low levels of psychological distress was associated with being aged ⩾30 years, self-identification as a nurse, having been negatively impacted finances due to COVID-19, perceived good to excellent status of own mental health (online Supplementary Table S1).

Higher levels of fear of COVID-19 were associated with being aged 30–59 years, females, perceived moderate to a great deal of distress related to the employment situation, having other comorbid conditions other than mental health issues, current alcohol consumption, unsure contact with known/suspected COVID-19 cases, having moderate to very-high levels of psychological distress, and using healthcare services to overcome COVID-19-related stress. On the other hand, lower levels of fear were associated with perceived own mental health as good to excellent, visiting a healthcare provider in the last 6 months, and having medium to high resilient coping (online Supplementary Table S2).

Higher levels of coping was associated with being aged 30–59 years, negatively impacted financially due to COVID-19, perceived mental health as good to excellent, and providing direct care to known/suspected COVID-19 cases. However, lower levels of resilient coping were associated with having psychiatric or mental issues, self-isolation (despite negative test results for COVID-19), and having high levels of fear of COVID-19 (online Supplementary Table S3).

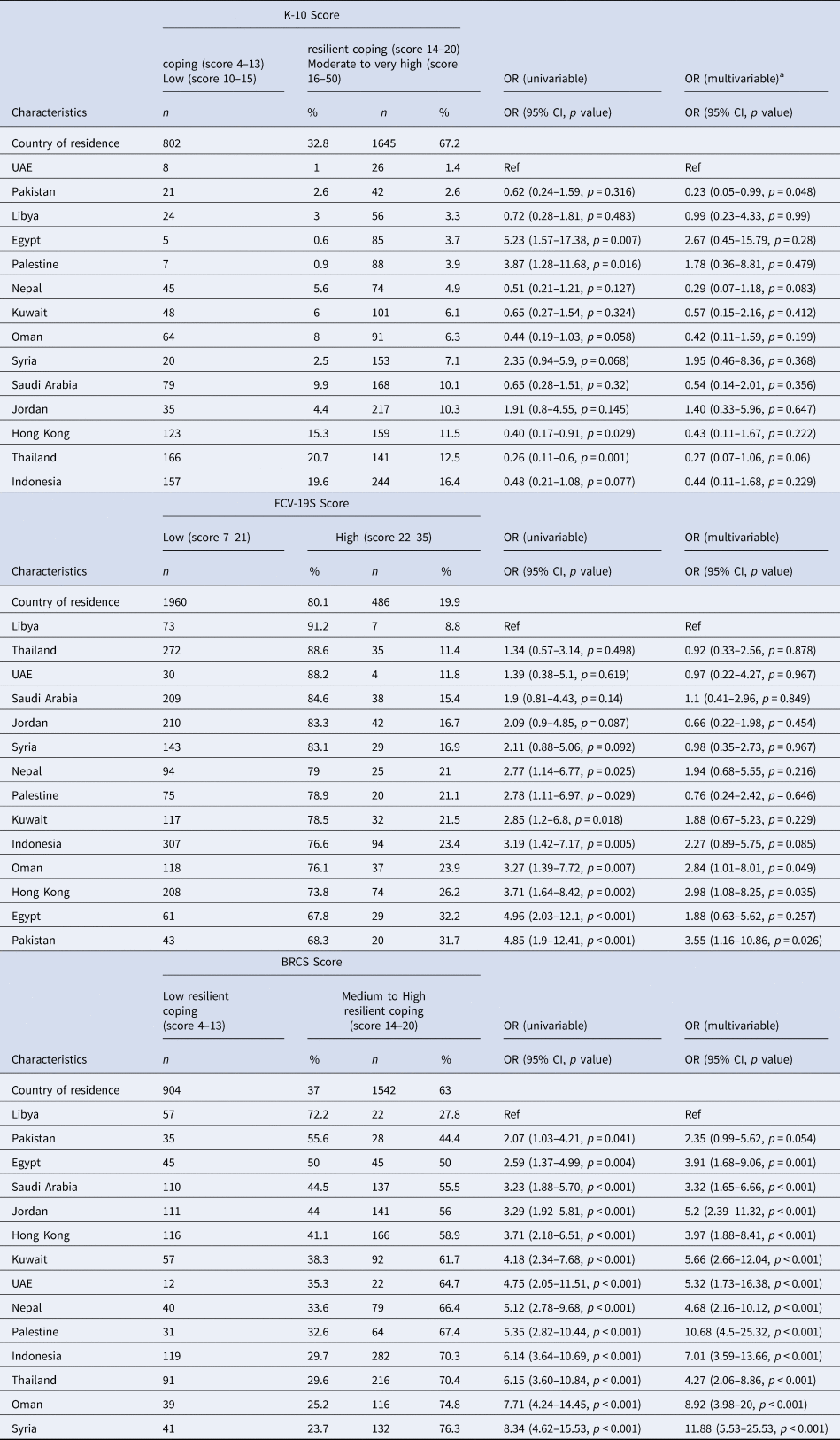

Psychological distress, fear, and coping per country

By country-wise analysis, the prevalence of moderate to very high psychological distress was variable within the participating countries, the lowest being in the UAE (1.4%) and the highest in Indonesia (16.4%). Compared to the UAE, the levels of psychological distress were significantly lower in Pakistan in the multivariate analyses. High levels of fear also varied across countries, being lowest in Libya (8.8%) and highest in Egypt (32.2%). Levels of fear among HCWs were found significantly higher in Oman, Hong Kong, and Pakistan when compared with the baseline country, Libya. Similarly, moderate to high coping scores varied across countries, the lowest being in Libya (27.8%) and highest in Syria (76.3%). Participants from all 13 countries exhibited significantly higher levels of coping compared to Libya (Table 5).

Table 5. Country-wise analyses for high psychological distress, fear of COVID-19, and coping among the study participants

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Adjusted for: age, gender, smoking, alcohol intake, living status, place of birth, country, education, employment status, employment stress, financial impact, contact with COVID-19 case, experience related to COVID-19, self-identification as a frontline or essential service worker, and healthcare service utilization.

Discussion

Key findings

Our study provided evidence relating to different factors associated with developing COVID-19-related psychological stress, fear, and coping among HCWs based on data from 14 countries across the globe. Findings indicated that factors, which were associated with both moderate to very-high levels of psychological stress and fear of COVID-19, were perceived distress related to employment status and comorbid conditions other than mental health issues. Moreover, higher levels of resilient coping were associated with being negatively impacted financially due to COVID-19, perceived mental health as good to excellent, and providing direct care to known/suspected COVID-19 cases.

Generally, those factors might be based on the nature of the work of HCWs, which implied that during the pandemic, they had been more frequently exposed to additional working hours and the increased risk of getting infected with COVID-19. For instance, psychological distress and fear of COVID-19 were emphasized in a previous study in Singapore, which included laboratory HCWs who were at a high risk of exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus from handling infected patients' blood samples, in addition to a marked increase in their workload (Teo et al., Reference Teo, Yap, Yip, Ong and Lee2021). Increased risk of transmitting the infection to other family members was also a contributing factor. We also found a significant correlation between living with family members and a high rate of moderate to high psychological distress. Furthermore, a previous systematic review showed that psychological distress was significantly correlated with being at risk of coming into contact with infected patients (Sirois and Owens, Reference Sirois and Owens2020). This was also consistent with our findings as we also found that contact with infected/suspected cases was significantly correlated with moderate-to-high psychological distress levels; it suggested that HCWs became more worried about not only getting infected and/or transmitting it when dealing with COVID-19 cases, but also they could potentially transmit to their family members (Koh et al., Reference Koh, Lim, Chia, Ko, Qian, Ng, Tan, Wong, Chew, Tang, Ng, Muttakin, Emmanuel, Fong, Koh, Kwa, Tan and Fones2005).

We also found that with or without testing positive for COVID-19, self-isolation was also correlated with fear of COVID-19, high psychological distress, and reduced coping scores. This might be attributed to the sense of isolation from the team, which could significantly affect the mental health of HCWs (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Socci, Pacitti, Di Lorenzo, Di Marco, Siracusano and Rossi2020). We found that doctors were more frequently exposed to developing moderate to high psychological distress, which was consistent with previous studies (De Kock et al., Reference De Kock, Latham, Leslie, Grindle, Munoz, Ellis, Polson and O'Malley2021; Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Shrestha, Baniya, Lamichhane, Shahi, Gurung, Tandan, Ghimire and Budhathoki2021). Nurses also reported high stress levels because they usually had more frequent contact with COVID-19 cases, higher workloads, and were more frequently females (Maunder et al., Reference Maunder, Lancee, Balderson, Bennett, Borgundvaag, Evans, Fernandes, Goldbloom, Gupta, Hunter, Mcgillis Hall, Nagle, Pain, Peczeniuk, Raymond, Read, Rourke, Steinberg, Stewart, Vandevelde-Coke, Veldhorst and Wasylenki2006). In our earlier investigation, we found that psychological distress was higher among doctors, with lower fear levels of COVID-19. Yet, medium to high coping levels were more frequent among nurses (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Islam, Tungpunkom, Sultana, Alif, Banik, Salehin, Joseph, Lam, Watts, Khan, Ghozy, Chair, Chien, Schonfeldt-Lecuona, El-Khazragy, Mahmud, Al Mawali, Al Maskari, Alharbi, Hamza, Keblawi, Hammoud, Elaidy, Susanto, Bahar Moni, Alqurashi, Ali, Wazib, Sanluang, Elsori, Yasmin, Taufik, Al Kloub, Ruiz, Elsayed, Eltewacy, Al Laham, Oli, Abdelnaby, Dweik, Thongyu, Almustanyir, Rahman, Nitayawan, Al-Madhoun, Inthong, Alharbi, Bahar, Ginting and Cross2021a). In the present study, no significance was found regarding resilient coping and fear of COVID-19.

Interestingly, we found that high resilient coping was associated with negatively impacted financial situations secondary to COVID-19, providing direct care for COVID-19 cases, high levels of fear, and self-isolation. This was evident in a previous study where better mental health outcomes were correlated with better adaptive personality traits (Sirois and Owens, Reference Sirois and Owens2020). In this context, applying mental health check-ups could be considered a helpful tool that could provide mental health support resulting in reduction of stress among HCWs (Ito and Matsushima, Reference Ito and Matsushima2017). Some studies have suggested that having a friendly authority to communicate experiences of psychological difficulties daily might be safer and more relaxing. There should be clear and transparent communication between healthcare facilities and HCWs to enable prompt referral to available psychiatric care or psychological counselling resources if required (Teo et al., Reference Teo, Yap, Yip, Ong and Lee2021). It was also pertinent that HCWs should have received regular and accurate updates of the COVID-19 situation, which could assist them in pre-empting their potential workload and allay their fears and uncertainties pertaining to work to ensure better coping related to the HCWs' day-to-day activities (Teo et al., Reference Teo, Yap, Yip, Ong and Lee2021). Taking into considerations the transcultural context within the participating countries, influence of social support, a frequently reported psychosocial resource of HCWs, was found to be a significant protective factor in terms of general mental health problems; that needs to be evaluated further and advocated to address both psychosocial stress and coping abilities.

Our findings also indicated wide variations in the burdens of psychological distress and fear of COVID-19 among HCWs. This could be explained in a number of ways: first, the relative quality of clinical care presented within healthcare systems was different among the countries participating in this study; second, limited resources could be more frequently associated with stress-related events; and third, more working hours could increase the risk of being infected, which significantly predisposed to developing psychological distress and fear of COVID-19 (Neto et al., Reference Neto, Almeida, Esmeraldo, Nobre, Pinheiro, De Oliveira, Sousa, Lima, Lima, Moreira, Lima, Junior and Da Silva2020). All those issues reiterate that when designing specific interventions, HCWs should not be considered a homogenous population as psychological impact will vary across this category of population.

There were some limitations to the findings of our investigation. Firstly, a potential selection bias might be present resulting from conducting the study through an online survey that limited recruitment of eligible HCWs, not those using the internet. Secondly, we did not have information on how exactly each country's healthcare system was affected by the pandemic and whether the HCWs were overburdened or not. Thirdly, the study's cross-sectional design also restricted us from conducting a proper predictive analysis. However, it should be noted that as a result of the current strategies to encounter the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the use of telehealth and social distancing, this study design was the most suitable and applicable option for investigating that situation. In addition, we collected data from 14 countries with a large sample size, which added to the strength of the current investigation.

Conclusion

Our study identified some important factors that could predict psychological distress and fear of COVID-19 and the level of resilient coping among HCWs. We found that age, perceived distress due to change of employment, co-morbidities other than mental health issues, perceived status of own mental health, being in contact with suspected/known cases, visiting a healthcare provider in the last 6 months for any reasons including COVID-related stress were significantly correlated with psychological distress, fear, and coping in this study. Therefore, it is most important to recognize the needs of HCWs and appreciate the factors that could significantly leverage their psychological wellbeing during such critical periods. Findings from this study might encourage healthcare authorities in different global communities to plan, develop, and implement adequate management strategies for HCWs, to support them psychologically during the critical period. The HCWs’ management plan should include an adequate supply of personal protective equipment, isolation of HCWs from their families during the infectious period, and development of an additional healthcare workforce to support the frontline HCWs in duties. Resilience and coping enhancement and/or fear and anxiety reduction programmes, in relation to COVID-19 impacts on employment/finance, health/illness conditions, and availability of appropriate healthcare services, could be considered. This intervention is highly important and essential specifically for those HCWs with moderate to high psychological distress and those with strong senses/feelings of self-isolation. Specifically with the ongoing pandemic along with emerging issues of new variants of COVID-19 which resulted in overwhelming burden on the HCWs, those measures could potentially reduce the frequency and severity of psychological wellbeing and improve the quality of care in clinical practice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.35.

Data

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support from all the collaborators and individuals who supported us in collecting data from the participating countries. Specifically, we would like to thank the investigators who supported us in coordinating data collection for the main study, but could not be part of this paper: Dr Agus Dwi Susanto, Dr Feni Fitrani Taufik, and Dr Tribowo Tuahta Ginting from Indonesia; Dr Manal Al Kloub from Jordan; Dr Alimajdoub Ali from Libya; Dr Turkiya Saleh Al Maskari and Dr Mara Gerbabe Ruiz from Sultanate of Oman; Dr Rayan Jafnan Alharbi and Dr Talal Ali Alharbi from Saudi Arabia; Dr Asmaa M Elaidy from Egypt; Dr Rania Dweik from United Arab Emirates; Dr Cattaliya Siripattarakul Sanluang, Dr Ratree Thongyu, Dr Suwit Inthong, and Dr Sirirat Nitayawan from Thiland. We would like to convey our gratitude to all the study participants, who donated their valuable time within the crisis period of coronavirus pandemic and kindly participated in this global study.

Author contributions

S. G. conducted data analyses and drafted the manuscript. M. A. R. was the lead investigator, who conceptualized the study and had the responsibility to coordinate with the study investigators for data collection in 17 countries. Data collection was coordinated by the respective country lead: S. G. in Egypt, A. H. A.-M. in Oman, S. A. in Saudi Arabia, A. H. and M. A. K. in Syria, D. H. E. in United Arab Emirates, F. Y. in Pakistan, M. H. in Kuwait, N. A. L. in Palestine, N. O. in Nepal, P. T. in Thailand, and S. Y. C. in Hong Kong. S. G. and M. A. R. interpreted data and prepared the results. All the authors provided critical feedback on narrative structure or methods or results. S. G., M. A. R., and W. M. C. finalized the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, accepted responsibility for its validity and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Financial support

We did not receive funding for this investigation.

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

Consent for publication

Data were collected anonymously, therefore, no identifying information were collected from the study participants.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee from each participating country: Egypt (Ain Shams University, Ref: FMASU R 121/2020), Hong Kong (The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Ref: SBRE-20-172), Indonesia (Universitas Indonesia, Ref: KET-1425/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPN.00.02/2020), Jordan (The Hashemite University), Kuwait (Kuwait University, Ref: VDR/EC/3693), Libya (Al-Brega General Hospital), Nepal (Kathmandu Medical College Public Ltd., Ref: 2611202004), Oman (Ministry of Health, Ref: MoH/CSR/20/24012), Pakistan (Lahore Garrison University), Palestine (Palestinian Health Research Council, Ref: PHRC/HC/768/20), Saudi Arabia (Ministry of Health, Ref: 20-605E), Syria (University of Aleppo), Thailand (Chiang Mai University, Ref: AF 04-021), and United Arab Emirates (Abu Dhabi University, Ref: CoHS-20-20-00024). Each study participant read the consent form along with plain language summary and ticked their consent in the online form prior to accessing the study questionnaire.