Impact statement

The involvement of people with lived experience (PWLE) of mental health conditions is crucial to improve mental health care. It has the potential to reduce mental health stigma and discrimination and address barriers to mental health care. However, a clear working guide for such involvement is lacking. This is particularly important in low- and middle-income countries where mental health services are expanding, but collaboration with PWLE is still in its nascent stage. Facilitated interaction between healthcare workers and PWLE can be achieved through the participatory action research technique “PhotoVoice.” The Reducing Stigma among HealthcAre ProvidErs to improve mental health services (RESHAPE-mental health) PhotoVoice guide provides a step-by-step approach in which PWLE use visual narratives to share their recovery stories for promoting social contact, debunking myths and reducing mental health stigma. The RESHAPE PhotoVoice guide is an open-access manual that can be freely adapted and used for collaborations with PWLE across culturally diverse settings. Furthermore, drawing on our experiences in using and adapting the RESHAPE PhotoVoice method across different settings, we critically reflect on the process and discuss its benefits and challenges for both the participants and researchers. We discuss the important ethical and practical challenges of using participatory visual methods, highlight the personal, therapeutic and social benefits for the participants and underscore the benefits of collaborating with PWLE for mental health researchers and program implementers. The RESHAPE PhotoVoice method provides researchers and organizations with a guiding framework for reducing stigma and enhancing the delivery of mental health interventions around the world.

Introduction

The benefits of collaborating with people with lived experience (PWLE) of mental health conditions in mental health research and program implementation are increasingly highlighted in the field of global mental health (Campbell and Burgess, Reference Campbell and Burgess2012; Semrau et al., Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm, Gureje, Hanlon, Jordans, Kigozi and Lempp2015; Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Upadhyaya, Magar, Giri, Hanlon and Jordans2017; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, West, Whitney, Jordans, Bass, Thornicroft, Murray, Snider, Eaton and Collins2023; Sartor, Reference Sartor2023). Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a guideline for the meaningful involvement of PWLE in health system strengthening including the co-creation, implementation and evaluation of programs and services that directly impact them (World Health Organization, 2023). Such collaboration not only enhances mental health care but also has the potential to challenge and transform the conventional top-down research approach, making PWLE an active partner in knowledge production and program implementation (Abayneh et al., Reference Abayneh, Lempp, Rai, Girma, Getachew, Alem, Kohrt and Hanlon2022; Doucet et al., Reference Doucet, Pratt, Dzhenganin and Read2022). It aims to balance the researcher–participant divide (Doucet et al., Reference Doucet, Pratt, Dzhenganin and Read2022) and engages PWLE as an expert in their own lives (Sartor, Reference Sartor2023). This can assist mental health practitioners, researchers and other stakeholders in gaining insight and understanding mental health through first-hand accounts, equipping them with meaningful solutions to collaboratively address mental health needs.

One method to facilitate collaboration with PWLE is through PhotoVoice, a participatory methodology using photographic storytelling (Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1997). Participants are asked to take pictures around their homes and communities depicting their lives as impacted by different health and social conditions. These pictures together with their stories are then used for initiating dialog and advocating changes.

The PhotoVoice approach places participants at the forefront, enabling them to identify and advocate for their own issues, and it values their lived experience as a central and key component for promoting change. A key feature of PhotoVoice is its ease of use in low-resource and low-literacy settings with participants not requiring any prior research or photography experience (Barry and Higgins, Reference Barry and Higgins2021) and adaptability across different groups and public health issues (Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1997).

Initially used in a participatory action research framework to understand the reproductive needs of women in rural China (Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1997), PhotoVoice has now been used in various domains of health research including mental health. PhotoVoice has been used to develop themes, format and content for a healthcare intervention (Cabassa et al., Reference Cabassa, Parcesepe, Nicasio, Baxter, Tsemberis and Lewis-Fernández2013b), for mental health education and advocacy (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Monahan, Monahan, Murphy, Ferguson, Lee, Bennett, Gibbons and Higgins2021b) and exploring motivation and challenges in seeking treatment (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Goodkind and Smith2011). The therapeutic benefit of PhotoVoice to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among survivors of sexual assault has also been evaluated (Rolbiecki et al., Reference Rolbiecki, Anderson, Teti and Albright2016). Other studies have used PhotoVoice to understand lived experiences of mental health conditions and recovery (Cabassa et al., Reference Cabassa, Nicasio and Whitley2013a; Muroff et al., Reference Muroff, Do, Brinkerhoff, Chassler, Cortes, Baum, Guzman-Betancourt, Reyes, López and Roberts2023).

With regard to stigma reduction, a randomized controlled trial was conducted on the benefits of PhotoVoice on self-stigma (Russinova et al., Reference Russinova, Rogers, Gagne, Bloch, Drake and Mueser2014). The trial developed anti-stigma PhotoVoice, a combination of photo narratives and psychoeducation on stigma, prejudice and discrimination; the nature and impact of prejudicial stereotypes; and strategies to cope proactively with stigma. Participation in the intervention significantly reduced self-stigma, increased the utilization of proactive coping mechanisms for societal stigma and increased the sense of community activism. Overall, the use of PhotoVoice across these studies contributed to improving mental health services and outcomes by providing first-hand understandings of issues and needs of PWLE to create tailored interventions and advocacy tools and improving therapeutic outcomes.

Based on these prior studies using PhotoVoice in mental health – most of which were conducted in high-income countries, we adapted PhotoVoice for use in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to reduce stigma among primary healthcare workers in Nepal (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Turner, Sikkema, Luitel, Rai, Singla, Lamichhane, Lund and Patel2018; Rai et al., Reference Rai, Gurung, Kaiser, Sikkema, Dhakal, Bhardwaj, Tergesen and Kohrt2018; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund and Patel2020). Since then, the use of PhotoVoice as a strategy for collaborating with PWLE to reduce health worker stigma and improve the quality of healthcare services has been used in Ethiopia, Tunisia, Uganda, India and China (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Turner, Sikkema, Luitel, Rai, Singla, Lamichhane, Lund and Patel2018, Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund and Patel2020; Abayneh et al., Reference Abayneh, Lempp, Rai, Girma, Getachew, Alem, Kohrt and Hanlon2022; Gronholm et al., Reference Gronholm, Bakolis, Cherian, Davies, Evans-Lacko, Girma, Gurung, Hanlon, Hanna and Henderson2023). Given the growing demand for guidance on the use of PhotoVoice to facilitate collaboration with PWLE in stigma reduction, our purpose here is to describe how PhotoVoice is a structured approach to enhance safe and effective collaboration to ultimately improve the quality of mental health services integrated into primary care settings, as well as the potential for other mental health service delivery.

In this study, we describe the process and its components based on experiences using and adapting PhotoVoice across three different settings: Nepal, Ethiopia and Uganda. We critically reflect on our experiences and discuss limitations and key considerations. We also propose other uses for improving mental health services in collaboration with PWLE and avenues for its future direction. Our aims are to:

-

• Provide a guiding framework for using PhotoVoice to collaborate with PWLE in anti-stigma and mental healthcare strengthening programs using recovery narratives in low-resource settings.

-

• Discuss the potential benefits and challenges of using PhotoVoice to collaborate with PWLE and provide a way forward for future research using this method.

Accompanying this article is the open-access manual Reducing Stigma among Healthcare Providers to improve mental health services (RESHAPE-mental health), which can be adapted and used freely for PWLE collaborations across culturally diverse settings (Supplementary Material).

The PhotoVoice approach

Our rationale for utilizing PhotoVoice as an anti-stigma intervention is based on theories of stigma in medical anthropology and social psychology (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund and Patel2020). Drawing from the seminal work in medical anthropology on “what matters most,” stigma is conceptualized as a moral phenomenon in which threats to personal and group identity within a particular local world can lead to stigmatizing behavior (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1999). For example, in the case of primary healthcare workers, their identity as a “healer” might be at risk when they interact with PWLE without proper training and resources for providing mental health services. This situation can lead them toward stigmatizing behavior.

In social psychology research, an important ingredient of stigma reduction is “social contact” (Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Tropp, Wagner and Christ2011). Social contact refers to interacting constructively between groups who previously held negative stereotypes, helping the members learn from and reflect on their biases (Allport et al., Reference Allport, Clark and Pettigrew1954). Consequently, attitudes and discriminatory behavior are reduced, as evidenced in studies where interventions bring together health workers and people with stigmatized conditions including mental health conditions (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Morris, Michaels, Rafacz and Rüsch2012; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Noblett, Parke, Clement, Caffrey, Gale-Grant, Schulze, Druss and Thornicroft2014; Nyblade et al., Reference Nyblade, Stockton, Giger, Bond, Ekstrand, Lean, Mitchell, Nelson, Sapag and Siraprapasiri2019). Contact-based interventions supported by education-based interventions where people openly interact and learn from each other have shown the most promising outcome of reducing stigma (Ashton et al., Reference Ashton, Gordon and Reeves2018; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Elshafei, Nguyen, Hatzenbuehler, Frey and Go2019; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Sunkel, Aliev, Baker, Brohan, El Chammay, Davies, Demissie, Duncan and Fekadu2022). Our approach of combining education with social contact focusing on “what matters most” of the target group and driven by the stigmatized population themselves incorporates the best evidence-based practices in the field (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund and Patel2020).

In particular, our use of PhotoVoice is to facilitate the creation of recovery stories and implement collaborative activities to address “what matters most” of the target group. For example, for a primary health worker audience, the recovery stories highlighted their professional values and roles, including the impacts they can make on their patients’ lives. This narration of recovery stories was combined with the interaction between the PWLE and the audience to maximize social contact. Additionally, with what has been highlighted as the “key ingredients of anti-stigma programs” (Knaak et al., Reference Knaak, Modgill and Patten2014), we included all these seven ingredients – personal testimony, multiple forms of social contact, focus on behavior change, myth-busting, an enthusiastic facilitator with a person-centered approach, recovery as key messaging and booster sessions within the process.

Adaptation of PhotoVoice to reduce stigma and improve quality within the healthcare system

The PhotoVoice process described here is based on the RESHAPE intervention, which aims in improving mental health service through stigma reduction (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund and Patel2020). The assumption is that when health workers are less stigmatized toward PWLE, they provide better care. To develop RESHAPE, the first step was identifying “what matters most” to the target group. Here, the healthcare providers identified different issues under survival, social and professional threats as root causes of stigma (Griffith and Kohrt, Reference Griffith and Kohrt2016; Stangl et al., Reference Stangl, Earnshaw, Logie, Van Brakel, Simbayi, Barré and Dovidio2019). Based on this, the second step was selecting the five intervention components to address this threat – recovery story and social contact, aspirational figures, myth-busting, stigma didactics and collaboration. Finally, as a third step PWLE were recruited and trained for delivering these components through PhotoVoice. More detail on this process is described elsewhere (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund and Patel2020).

Based on this intervention, the PhotoVoice training was developed to address mental health stigma among healthcare providers in collaboration with PWLE. We conducted extensive discussion with PWLEs in developing the themes, contents and methods of the training. Interviews were also conducted with the caregivers, trainers, counselors and the audiences of the recovery stories in understanding their reflection on the process. A theory of change was conducted with PhotoVoice participants in Nepal discussing the process and potential avenues of their involvement after completing the training.

Throughout the training, we placed equal emphasis on both the “product,” that is, the recovery story – and the “process,” that is, the development of the story, as key primary outcomes (Haskie-Mendoza et al., Reference Haskie-Mendoza, Tinajero, Cervantes, Rodriguez and Serrata2018; Shaw, Reference Shaw2020). The participant’s life experience was central in understanding and addressing the issue. Recognizing the difference in an individual’s experience and needs, iterative adaptation was made throughout the process. Across different settings, we focused more on innovation than replication.

A similar cross-cultural adaptation process was pursued in Ethiopia and Uganda. In Uganda, we conducted a theory of change exercise with PWLEs, and in Ethiopia, we conducted discussions with local researchers, practitioners and PWLE for PhotoVoice adaptation (Abayneh et al., Reference Abayneh, Lempp, Rai, Girma, Getachew, Alem, Kohrt and Hanlon2022). The first and second authors trained the staff in all these countries on the PhotoVoice approach. Our descriptions below are based on the implementation of PhotoVoice in these countries.

Recruitment of PWLE

We recruited PWLEs for six batches of PhotoVoice training in three field sites – four batches in Nepal (n = 30), one batch in Ethiopia (n = 12) and one in Uganda (n = 10). The general criteria were for PWLEs to be clinically diagnosed with mental health conditions, be in recovery and have the capacity to provide consent for taking part in the PhotoVoice training and subsequent activities. Participation in PhotoVoice training did not commit them to participate in the future training of healthcare workers. Participation of their caregivers in the PhotoVoice training was encouraged (Rai et al., Reference Rai, Gurung, Kaiser, Sikkema, Dhakal, Bhardwaj, Tergesen and Kohrt2018), but not compulsory. After completion of training, PWLE, together with the PhotoVoice trainers and their mental health providers, made decisions about their continuation in the healthcare worker training.

Description of PhotoVoice training

The PhotoVoice training consisted of structured 10–12 sessions of didactics, group and individual exercises and practice. The initial 2–3 sessions were conducted as residential training to build group relationships and foster trust among the participants and the trainers. The remaining sessions were conducted as weekly or biweekly sessions based on the feedback and availability of the participants. Periodic refresher sessions were also conducted at each site depending on the participant’s needs assessment. Each site invited and encouraged the involvement of family members or caretakers throughout the process.

The end goal of the PhotoVoice training was 6–7 minutes of PhotoVoice-based recovery narratives. While the primary audience of the PhotoVoice stories was the primary healthcare workers, we also adapted them to meet the needs of diverse audiences including general community members and policymakers. The content and focus of these PhotoVoice stories were tailored to cater to specific audiences. For example, for a primary healthcare worker audience, the focus of the narrative could be on the role the PWLE’s primary healthcare center played in their recovery, and for a policy-making audience, the focus was on the structural barriers such as lack of regular supply of medication and the role they could play to address them.

The participants started with writing their recovery stories and learning how to use cameras. Then, they went back to their home and communities taking pictures representing their stories. Participants were asked to take as many pictures as they wanted but ultimately selected 5–6 photographs that best depicted their stories.

The photographs chosen by participants were either direct representations of their story, such as a picture of a goat showing income generation activity, or metaphoric representations, such as a pitch-black photograph depicting the state of their mind during time of distress. As external researchers, our role was to support participants in brainstorming ideas and finding suitable photographs along with teaching them the skills to take photographs. Participants presented their photographs and stories during practice sessions and received feedback from their peers. Additionally, previously trained participants served as trainers in subsequent iterations of the PhotoVoice training, sharing their own experiences and facilitating the process for new participants. Besides the photograph and story production, the PhotoVoice training included sessions on skill development and self-care.

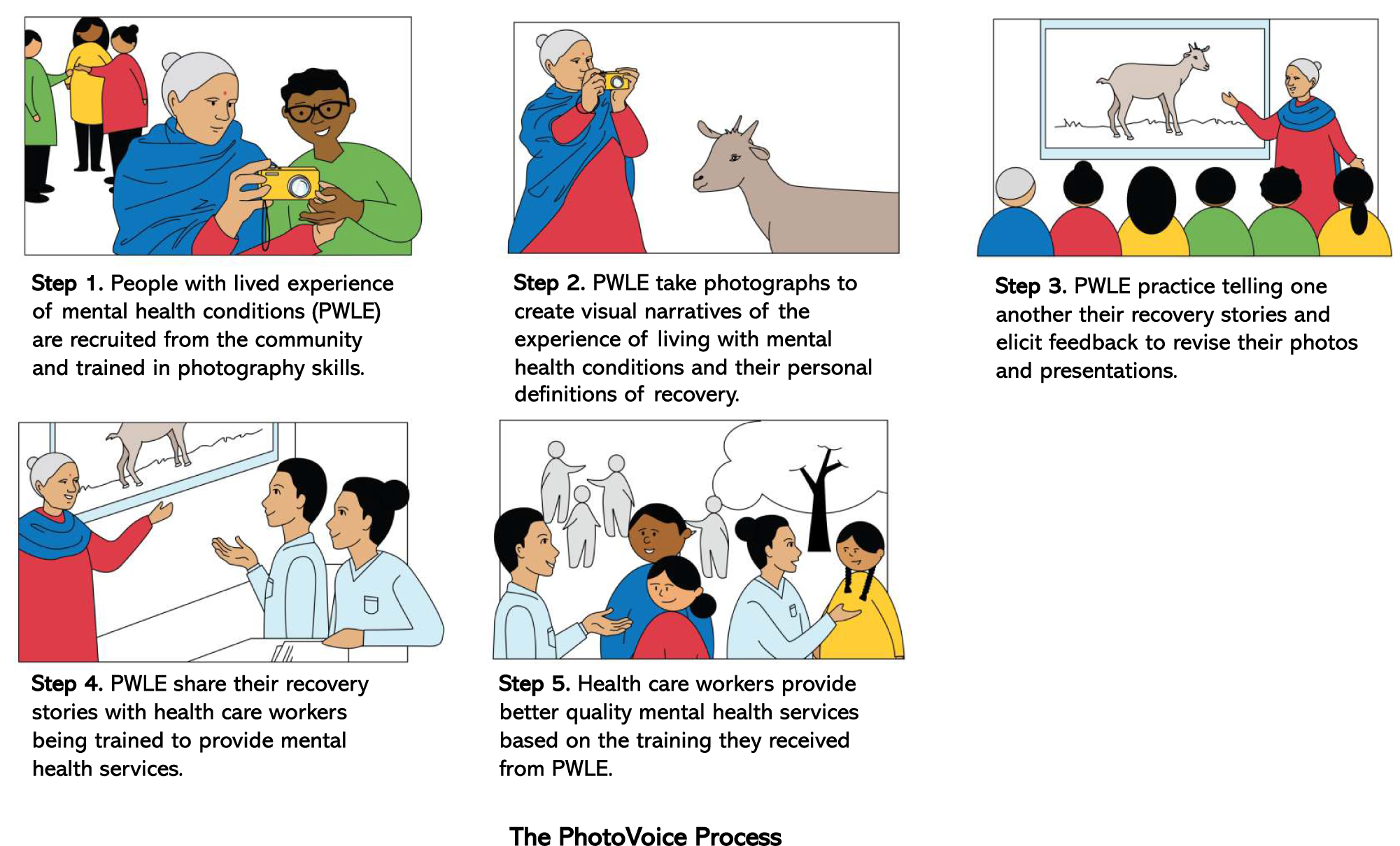

The PhotoVoice process and product were designed to be adaptable and iterative based on the participant’s feedback, the project goals and the local context. However, we developed a number of core elements to provide the process with a structure. These core elements representing the basics of the PhotoVoice method are shown in Figure 1 and are described as follows.

-

1. Recovery stories: Each PWLE created their personal recovery stories based on their experiences of mental health problems. These stories highlighted their struggles with mental health problems, how they addressed them and their current recovery. Though each story was organically created, we developed a helpful guideline to structure the stories and divided them into three sections.

-

• Life during mental health problem

-

• Life during treatment

-

• Life during recovery

The first part described the impact on their daily life and families, their experience of stigma, physical and mental symptoms and the different treatment methods they underwent. The second part described their pathway to care, the usage of health services, the role of medication and counseling and the role of family members. The third part described the changes in their physical and mental health symptoms, their functioning, their relationship with family members and the community and the impact on their work.

With the help of the training facilitators, each participant wrote their recovery stories during the initial sessions. They were then reviewed for clarity, content, structure and length by the training facilitators and their peers.

-

-

2. Disclosure: PhotoVoice stories are personal stories where the PWLE talk about their mental health problems. As mental health is highly stigmatized, it is likely that PWLE may not have disclosed their status to people around them. Therefore, we conducted sessions on disclosure to help PWLEs open up about their status. This included topics on destigmatizing mental health, including caregivers and family in the process, recognizing strengths and mapping resources for support.

-

3. Learning to use cameras: We used basic digital cameras for the process. Because all the PWLEs had limited exposure to technology, they were taught from the basics: learning how to turn the cameras on or off, picture orientations and zooming the subjects. The participants first practiced in-session and in-training sites by clicking pictures of each other and places or things they saw. Taking pictures of people in public was discouraged in the initial phase of the training because of consent issues.

-

4. SHOWED method: SHOWED method provides the following guidelines for eliciting discussion on the participant’s photographs (Wang, Reference Wang1999):

-

• What do you See in the picture?

-

• What is Happening in the picture?

-

• How is it related to Our life?

-

• Why does this condition exist?

-

• How can we be Empowered by understanding this issue?

-

• What can we Do to address it?

As recovery narratives in this PhotoVoice are a combination of 5–6 photographs representing different parts of their story, together with PWLEs we realized that these questions can be discussed using different photographs within the presentation. Thus, we adapted it by having the first four questions as necessary to address each photograph and the last two questions addressed as relevant.

-

-

5. Presentation skills: One of the primary outcomes of the PhotoVoice process is to have PWLE tell their stories to different audiences, which requires public speaking skills. Thus, we conducted sessions on presentation skills, public speaking, answering questions and dealing with challenging situations. Each site conducted these using didactics, role plays and exposing them to different audiences during the end sessions.

-

6. Understanding distress and distress management: The PhotoVoice method requires the PWLE to recall and discuss their past, which can be stressful and distressing. To address this, the participants went through sessions on understanding their distress and learning ways to address it. This included didactics, skills in self-care, deep breathing and mapping resources for help-seeking. Throughout the sessions, all the sites ensured the presence of trained mental health practitioners to deal with stressful events and facilitate self-care activities. Referral pathways were also established in case the participants required specialized care.

-

7. Stigma: As interventions in all three sites aimed at reducing mental health stigma, we made stigma one of the core components of the PhotoVoice training. The PWLEs went through didactic and group discussion sessions on understanding and addressing stigma. It included elucidation of local stigmatizing words and their non-stigmatizing alternatives, understanding myths and facts on mental health stigma and ways to deal with self and community stigma.

Figure 1. Core components of PhotoVoice training.

An example of a recovery story and some photographs representing the story is presented in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Table 1. Example of recovery story from Nepal

Figure 2. Examples of photographs used in PhotoVoice by PWLE in Nepal.

Using PhotoVoice narratives in mental health trainings of primary healthcare workers

The PhotoVoice training in Nepal, Ethiopia and Uganda was part of a larger mental health intervention, where primary healthcare workers were trained using the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) (World Health Organization, 2010). This training ranged from 5 to 10 days and covered depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder and psychosis. During each training, the trained PWLEs were involved in (1) structured sessions – telling their PhotoVoice stories, subsequent discussions and collaborative activities based on jigsaw classroom activity (Allport et al., Reference Allport, Clark and Pettigrew1954) and (2) unstructured sessions – informal interactions with the health workers during breaks and group discussions.

PWLEs were invited to the training matched on their clinical diagnosis and the focus disorder of the day. They also took part in sessions on communication skills, stigma and group exercises on addressing potential barriers to care. An example of such a training curriculum in Nepal is presented in Figure 3. More details on the results of these trainings are described elsewhere (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund and Patel2020).

Figure 3. Example of health worker training curriculum showing involvement of PWLE and use of recovery stories and PhotoVoice.

Involvement in other aspects of health system strengthening

-

1. Community intervention: The trained PWLEs took part in community-level programs for raising mental health awareness and developing referral mechanisms for care in Nepal. Telling their stories and interacting with the public, some of them functioned as informal community mobilizers supporting people with mental health issues and bringing them to care.

-

2. Policy advocacy: In Nepal, together with the implementing institution – TPO Nepal, the PWLEs conducted advocacy programs with the local policymakers. One such example of their work was collaboration with the Health Facility Management and Operation Committee (HFMOC), which is a local, health facility-specific committee responsible for planning and budgeting. The PWLEs through their recovery narratives and subsequent discussions highlighted the need for policy-level interventions in issues including medication supply, staff management and budget and resource allocations.

-

3. Program design and implementation: In Nepal and Ethiopia, the trained PWLE were a part of the group in designing and implementing a mental health program called RESHAPE. They participated in program design through the theory of change workshop and facilitated subsequent PhotoVoice training.

Safety and well-being of PWLE during collaboration

To ensure the safety and well-being of participants throughout the collaboration process, we implemented several measures. Before starting PhotoVoice training, participants were individually contacted by counselors who assessed their readiness for participation. The pair also discussed their potential story, and to avoid potential trauma, they decided on parts of the story they felt comfortable sharing and parts they wanted to avoid. This was further supported by stepwise disclosure during the main session.

During the PhotoVoice training, counselors regularly practiced relaxation exercises. The PhotoVoice sessions were formatted as a form of group therapy where the participants reflected on each other’s issues, provided peer support and conducted group problem-solving ensuring the therapeutic benefit of the process. A checklist covering domains such as symptom presentation, stigma and family support was also developed and periodically administered, helping the facilitators identify any unintended consequences of participation and the need for immediate support.

During the public presentation of their stories, PWLE were supported by facilitators who helped them in managing any potential challenges including stigma and discomforting questions. Before going public, we conducted intensive sessions on “public speaking” and “addressing difficult questions” and dedicated a significant amount of time to practice storytelling. Additional sessions were conducted if either the PWLE or facilitators felt the need for further preparation.

Impact of PhotoVoice-based collaboration of reducing stigma and health systems strengthening

While the full trial for RESHAPE is currently undergoing, data from the pilot RESHAPE study showed promising outcomes (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Turner, Rai, Gurung, Dhakal, Bhardwaj, Lamichhane, Singla and Lund2021). Primary health workers trained in the RESHAPE arm (mhGAP + PhotoVoice) had a 10.6-point reduction on the Social Distance Scale compared with 2.8 points for those trained in Implementation as Usual arm (IAU), which included only mhGAP training. Diagnostic accuracy was also better in the RESHAPE arm with 72.5% accuracy compared with 34.5% in the IAU arm.

Benefit to the participants

Attention to empowerment and maximizing the benefits of the process to end users are core components of participatory action research. In PhotoVoice, the focus on the “process” along with “product” ensured PWLE benefited not only from the larger intervention but also from their participation in the PhotoVoice training. Therapeutic benefits were observed across sites with PhotoVoice sessions taking the form of group therapy. We observed PhotoVoice providing the participants with a community they can relate to and an avenue to share their stories and feel lighter. A recurring observation highlighted by the participants was the opportunity to connect with others who shared similar experiences, which provided them with a profound realization that they were not alone. In Nepal, participants described the training as a safe nonjudgmental space where they can openly talk about their issues. Besides, the PhotoVoice sessions included components of self-care, distress management and self-stigma. Having direct access to trained mental health practitioners throughout the training also maximized their therapeutic benefits.

Social benefits included identification and access to resources via training participation and increased social capital. In Sierra Leone, former child soldiers who were part of the PhotoVoice process experienced social benefits in terms of their community not seeing them as violent people but as photographers (Denov et al., Reference Denov, Doucet and Kamara2012). A similar pattern was observed here with participants reporting noticeable shifts in community attitudes toward them as training facilitators and recognizing their ability to support others.

In terms of empowerment, the biggest perceived benefit to the participants is the ability to find skills and agency to advocate their issues and be in charge. During the PhotoVoice training, PWLEs had the opportunity to openly discuss their mental health condition and challenges with those who held considerable influence including healthcare workers, policymakers and caregivers.

Reflection and considerations

Although recovery narratives are intended to be the products of PWLE, it is necessary to reflect on the role and impact of external guidance during the process. Recovery stories are not “unconscious production but are rather carefully constructed and contextually situated” (Jacobson, Reference Jacobson2001; Burgess and Fonseca, Reference Burgess and Fonseca2020; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Varma, Carpenter-Song, Sareff, Rai and Kohrt2020). In the PhotoVoice training, the construction of the recovery stories was organic considering every participant authoring their own story based on their experiences but again guided because we provided them with themes and structures to write it. For example, we did not define what “recovery” means for them, but they elicited its meaning through their photographs and stories. This resulted in the generation of unique ideas and understanding of recovery – people describing their ability to care for their children and family, engage in income-generating skills or become role models in their community by helping people with similar problems or being part of community groups who previously stigmatized them. Others had more individual understanding of recovery – being able to sew clothes or paint after the remission of symptoms such as trembling hands and inability to concentrate.

The participants also received feedback from their peers and facilitators. In addition, stories had to fit within a 6- to 7-minute structured session. This might sometimes lead to the possibility of their stories being manipulated and filtered. However, peer learning is a part of the collaborative process, and we assume that getting feedback from people who have gone through similar issues does not necessarily take away the originality of the narratives, but rather strengthens it and facilitates reciprocal learning. As for the facilitator’s feedback and structured narratives, our experience showed that unstructured narratives can often be chaotic, lose focus and even contribute to further stigmatization and negative consequences. This was also supported by participants who mentioned that having some structure and feedback can support their storytelling.

Ethical consideration in participatory research is often contested in terms of the need for active collaboration with end users and underlying possible risks to the participants (Switzer et al., Reference Switzer, Guta, de Prinse, Carusone and Strike2015; Shaw, Reference Shaw2020). Similarly, there can be instances of coercive production of narratives tied to treatment provision (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Varma, Carpenter-Song, Sareff, Rai and Kohrt2020) or as a part of the healing process (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2013) or project expectation (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Monahan, Ferguson, Lee, Kelly, Monahan, Murphy, Gibbons and Higgins2021a). In an example of such narratives from Kashmir, recovery narratives were a necessary requirement for discharge from in-patient care from a substance abuse treatment facility (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Varma, Carpenter-Song, Sareff, Rai and Kohrt2020). In terms of visual methods such as PhotoVoice, this issue becomes further complicated regarding the need for maintaining confidentiality versus the need of being open and honest in public. In this PhotoVoice, we were collaborating with people who are highly stigmatized and living in close-knit communities where people are likely to know each other. Participating in this training and subsequent activities had the potential to expose their mental health condition to the public risking further stigmatization. Within the training program, the participants were engaged in recalling, writing and sharing their personal stories, which might not be pleasant to talk about and might induce painful memories and trauma. Often during these sessions, we had participants break down in the middle of their stories.

Nevertheless, tensions are inevitable and require strategic attention to minimize harm and maximize the potential benefits. Completely avoiding harm means inaction, which is potentially more harmful than those added risks. The perspective of a stigmatized group as PWLE, by definition, rarely comes into public, and their active participation rarely occurs (Shaw, Reference Shaw2020). Thus, there is a concurrent danger in bringing these things to the public. Here, while there was a need for maintaining confidentiality, it was equally necessary for PWLE to be open about their story.

Recognizing these possible ethical issues and risks, we codeveloped safety strategies with PWLE. Participants and their families were made aware of the possible risks, and the need to complete the PhotoVoice training and participate in subsequent activities was never tied to their care and support provision. The disclosure was not a one-time activity but was slowly done across the sessions with the active involvement of their family members. We made sure participants had enough practice before going public. Anticipating possible distress, the provision of having a trained mental health worker during the training and subsequent activities was made mandatory, and skills of self-care and distress management were included as an important part of the training. During the start of each session, we checked in with each participant about their feelings and challenges.

Challenges and limitations

As with other participatory action research, the use of PhotoVoice comes with challenges and limitations. Studies have noted challenges including issues with confidentiality (Shaw, Reference Shaw2020), consent and distress (Creighton et al., Reference Creighton, Oliffe, Ferlatte, Bottorff, Broom and Jenkins2018), expectations (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Monahan, Ferguson, Lee, Kelly, Monahan, Murphy, Gibbons and Higgins2021a) and maintaining power dynamics (Sutton-Brown, Reference Sutton-Brown2014). For example, critical examination of language, structure and assumption within the process may reify the very hierarchical power relations they aim to resist (e.g., participants described as marginalized, vulnerable and silenced) (Sutton-Brown, Reference Sutton-Brown2014). While PhotoVoice may not represent a perfect utopian form of Participatory Action Research (PAR), it remains one of the most effective methods currently available for fostering meaningful and equitable collaboration (Barry and Higgins, Reference Barry and Higgins2021).

The PhotoVoice process described here was based on the principles of Participatory Action Research. However, we recognize the possibility of the process being influenced by the project objectives and staff during certain parts of the training and subsequent intervention. Additionally, the project’s access and control of the resources might have led to social desirability. While no significant adverse events were observed linked to the participation of PWLEs in the program, it is crucial to acknowledge the possibility of incidents that might have occurred beyond our scope of observation.

While the paper provides a guideline for using PhotoVoice for stigma reduction research, the methods we describe here are based on an iterative adaptation process. Contextual factors should be considered before using this method in other settings.

Conclusion and future direction

We found PhotoVoice to be an effective method of participatory action research, collaborating with PWLE of mental health conditions to reduce stigma. PhotoVoice had its benefits to both (1) the project, in terms of its collaborative approach allowing the study to understand the issue and advocate change from the end user’s perspective, and (2) the participants, in terms of empowerment and social and therapeutic benefits. However, caution needs to be taken for using visual methods requiring disclosure such as PhotoVoice, keeping in mind the participant’s safety and ethical considerations.

Our approach in combining PhotoVoice with the mhGAP training also opens the possibility to include it with other psychological interventions. As PhotoVoice is very adaptive and flexible, it could be used for other target populations including counselors, trainers and teachers and for addressing issues including but not limited to mental health stigma.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.73.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.73.

Data availability statement

This is a methods overview paper and does not have any original data. Data related to this study can be acquired through the original publication (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Turner, Rai, Gurung, Dhakal, Bhardwaj, Lamichhane, Singla and Lund2021).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants in the PhotoVoice training. The authors thank Nepal Health Research Council, Dr Kamal Gautam (Executive Manager, TPO Nepal), RESHAPE research and clinical staff of TPO Nepal, especially Sabitra Sharma (psychosocial supervisor). The authors especially thank Adesewa Adekelun, Ritika Singh, Brian Byamah Mutamba, Edith Kebirungi, Lynn Semakula, Sisay Abeyneh and Charlotte Hanlon, Cheenar Shah and Ruta Rangel.

Author contribution

B.K. conceptualized the study, acquired funding, supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript. S.R. codeveloped and implemented the study and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. D.G. codeveloped, implemented and reviewed the manuscript.

Financial support

This study was supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (B.K. Grant Nos. K01MH104310-01, R21MH111280 and R01MH120649), Wellcome Trust (B.K. Grant No. 223791/A/21/Z) and the UK Medical Research Council (B.K. Grant No. MR/R023697/1). The funding body did not participate in the design of the study; collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; and writing of the manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

Studies covered by this article have been granted ethical approval by Duke University (Pro00055042 and Pro00073426) and George Washington University (051741, 051725 and NCR191416). Ethical approval was received from the Nepal Health Research Council (110/2014, 139/2016 and 441/2020) in Nepal, Addis Ababa University College of Health Sciences (AAUMF01-008) in Ethiopia and Makerere University School of Public Health IRB (SPH-2022-232) and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (HS2327ES) in Uganda. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Comments

19 July 2023

To: Editors in Chief, Cambridge Prism Global Mental Health

Prof Judy Bass, John Hopkins University

Dr Dixon Chibanda, Friendship Bench Zimbabwe

Dear Drs:

My colleagues and I are submitting a manuscript for your consideration for review and publication in Cambridge Prism Global Mental Health. The manuscript is entitled:

“The photovoice method for collaborating with people with lived experience of mental health conditions to strengthen mental health services”.

This manuscript presents a detailed description of the PhotoVoice, a type of Participatory Action Research, which involves collaboration among people with lived experience of mental health conditions (PWLE) to address mental health stigma among primary healthcare workers. This method is used in randomized controlled trials in Nepal and Uganda funded by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health and the Wellcome Trust. This method has now been adopted by the INDIGO project, which is implementing it in seven sites across five different countries, including China, India, Nepal, Ethiopia, and Tunisia, through funding from the UK Medical Research Council. Drawing on our eight years of experience in developing and adapting this method for stigma reduction, in this manuscript, we provide a thorough explanation of the approach and reflect on our lesson learned and way forward.

Given the Cambridge Prism: Global Mental Health audience, we have geared this article to global health practitioners who are committed to collaborating with people with lived experience of mental health conditions (PWLE). This manuscript provides the rationale for using PhotoVoice in collaboration with PWLE and the steps on how to conduct this approach in other settings. We feel this will be a highly used article in the field because of its practical step-by-step guidance.

Till date to our best knowledge, no paper has documented this method in context of mental health stigma in LMIC settings. This manuscript provides the rationale for using PhotoVoice in collaboration with PWLE and the steps on how to conduct this approach in other settings. We feel this will be a highly used article in the field because of its practical step-by-step guidance. Accompanying this article, we provide the first an open-access manual “Reducing Stigma among Healthcare Providers to improve mental health services” (RESHAPE-mental health), which can be freely adapted and used for collaborations with people with lived experience of mental illness across culturally diverse settings.

We believe this manuscript aligns with the objective of the journal, by proposing an innovative method in addressing two of the biggest challenges in global mental health – stigma and meaningful collaboration with people with lived experience. Ultimately, our proposed method aims to improve the quality and accessibility of mental health services in primary and low-resource settings by tackling the issue of health workers stigma.

Please contact us if any additional materials are required for the submission. I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

Sauharda Rai, MA, PhD

Research Scientist

Center for Global Mental Health Equity

George Washington University

Washington DC, USA

Dristy Gurung, MSc Global Mental Health

Research Manager

Transcultural Psychosocial Organization – Nepal

Kathmandu, Nepal

Brandon Kohrt, MD, PhD

Charles and Sonia Akman Professor in Global Psychiatry

Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Global Health, and Anthropology

Director, Center for Global Mental Health Equity

George Washington University