Introduction

The global burden of mental health has become an increasingly important topic to understand. Mental health disorders have increased in prevalence globally, across diverse demographics, cultures, and political situations (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana, Bolton, Chisholm, Collins, Cooper and Eaton2018). The burden of mental illness is disproportionately high in low- and middle-income nations. Some low-income country populations, particularly in Asia (Lauber and Rössler, Reference Lauber and Rössler2007; Giasuddin et al., Reference Giasuddin, Levav and Gal2015), believe that mental health issues result from religious, familial, or cultural disobedience (Ndetei et al., Reference Ndetei, Khasakhala, Mutiso and Mbwayo2011). This belief is associated with stigma around mental health (Uddin et al., Reference Uddin, Bhar and Islam2019) leading to decreased use of professional mental health care (Koly et al., Reference Koly, Abdullah, Shammi, Akter, Hasan, Eaton and Ryan2021). Therefore, determining how to promote positive views and utilization of mental health care in low- and middle-income nations is critical to increase mental wellbeing in this population.

Mental disorder rates generally rise in young adulthood. In Bangladesh, early adulthood is the most vulnerable period for depressive symptoms (Arafat, Reference Arafat2019). Given the high levels of stress college students face (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Hunt, Speer and Zivin2011) and the link between stress and depression (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Angermeyer, Anthony, DE Graaf, Demyttenaere, Gasquet, DE Girolamo, Gluzman, Gureje, Haro, Kawakami, Karam, Levinson, Medina Mora, Oakley Browne, Posada-Villa, Stein, Adley Tsang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee, Heeringa, Pennell, Berglund, Gruber, Petukhova, Chatterji and Üstün2007; McGorry, Reference McGorry2011), college students are at high risk of developing depressive symptoms (LeMoult, Reference LeMoult2020). Early management of depressive symptoms is essential, as treatments can be less effective as the duration of depression increases (Bukh et al., Reference Bukh, Bock, Vinberg and Kessing2013).

Several studies have assessed depression in Bangladeshi university students using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). In a study of 665 university students, Hossain et al. (Reference Hossain, Anjum, Uddin, Rahman and Hossain2019) found that 74.1% had mild to severe depression. Koly et al. (Reference Koly, Abdullah, Shammi, Akter, Hasan, Eaton and Ryan2021) found that 47% of the sample met the criteria for depression and that poor academic performance and excessive use of social media were the most common factors that were associated with depression in college students. Islam et al. (Reference Islam, Sujan, Tasnim, Sikder, Potenza and van Os2020) showed that 69.5% of first-year students (n = 400) experienced moderate to severe depression. Using Beck's Depressive Inventory, Sayeed et al. (Reference Sayeed, Hassan, Rahman, El Hayek, Al Banna, Mallick, Hasan, Meem and Kundu2020) discovered, in a cross-sectional study of 404 college students, that 47.5% had depression and 8.7% had attempted suicide. Despite strong data supporting the prevalence of depression among Bangladeshi university students, there is little research on utilization of mental health services to reduce depressive symptoms.

Despite the prevalence of mental health disorders, there has historically been a lack of both health care providers that are trained in psychiatric health (World Health Organization, 2007). A report of the assessment of the mental health system in Bangladesh using the World Health Organization – Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS) was undertaken in 2007 to examine the current situation in Bangladesh regarding mental health. Bangladesh has one main mental health hospital, and 50 outpatient mental facilities, but there is no follow-up care provided for patients once they leave the facility (WHO-AIMS). Further, only 4% of medical doctors in Bangladesh are trained in mental health, and 2% of nurses have specific mental health training (World Health Organization, 2007), and only 1–20% of primary care physicians make at least one referral to a mental health professional. However, in recent years, there has been a push to scale up mental health services in low-income countries by global leaders such as the WHO, the Lancet, and the World Bank.

It is important to understand the motivations and hesitancies toward seeking and receiving mental health care, particularly in populations where stigma levels are historically high. A systematic review of published literature related to mental health disorders and mental health services in Bangladesh indicated that there are low community awareness of mental health disorders, negative attitudes toward treatment, and low priority for treatment even among those affected by mental health disorders (Hossain et al., Reference Hossain, Ahmed, Chowdhury, Niessen and Alam2014). Low awareness of mental health is troubling, because if one does not recognize the need for care, they are less likely to receive care (Bilican, Reference Bilican2013), as such perceived need is an important outcome to examine and is an important first step to receiving care. Positive attitudes toward clinical mental health care are linked to mental health-seeking behavior (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Wang, McDermott, Kridel and Rislin2018), therefore promoting mental health awareness and the use of services is critical, as research shows that mental health services such as therapy and medication are effective (Hollon et al., Reference Hollon, Thase and Markowitz2002; Hollon et al., Reference Hollon, DeRubeis, Shelton, Amsterdam, Salomon, O'Reardon, Lovett, Young, Haman, Freeman and Gallop2005). For example, one study found that cognitive behavioral therapy significantly improved negative mental health symptoms related to post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety when compared to people who did not engage in therapy (Mueser et al., Reference Mueser, Rosenberg, Xie, Jankowski, Bolton, Lu and Wolfe2008). Further, medications such as sertraline have been shown to improve post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology when compared to patients taking a placebo (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Rothbaum, van der Kolk, Sikes and Farfel2001).

Nonclinical strategies including adaptive coping skills and social support have been found to improve an individual's mental health. Coping skills can improve mental health, particularly under tough situations (Meyer, Reference Meyer2001; Garcia et al., Reference García, Barraza-Peña, Wlodarczyk, Alvear-Carrasco and Reyes-Reyes2018). There is minimal research on Bangladeshi university students' coping mechanisms. During the COVID-19 pandemic, one study found that college students with ‘high extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness and low neuroticism’ had higher abilities to participate in healthful behavior (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Hossain, Siddique and Jobe2021). Understanding present coping strategies is crucial to develop mental health interventions for Bangladeshi students.

Theory

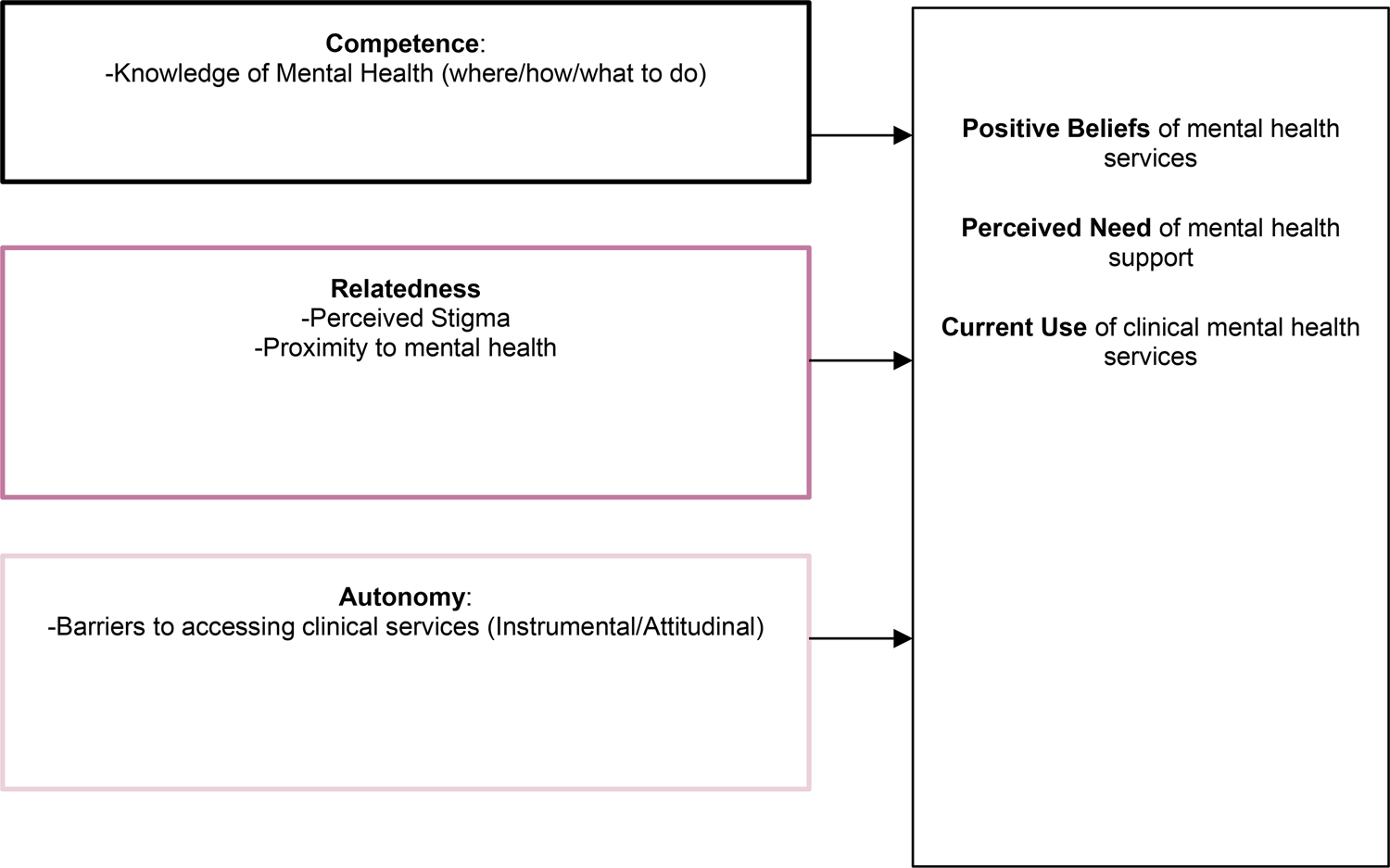

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a useful framework to understand the motivation to engage in a particular behavior. SDT states that motivation for a behavior derives from three natural and psychological needs: competence, psychological relatedness, and autonomy (Vansteenkiste et al., Reference Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Sheldon and Deci2004). The construct of competence refers to the feeling that a person has a sense of mastery in their actions, and can be assessed by examining one's perceived knowledge on the subject. Researchers define the construct of ‘mental health knowledge’ based on participants' knowledge of the symptoms and effects of mental health illnesses that are defined by Western countries, like the United States, but these definitions are not widely established in non-Western countries (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Zane, Nagayama Hall and Berger2009). Therefore, when studying mental health in Bangladesh, it is critical to focus on the sample's culture and language around mental health (Rodrigo, Reference Rodrigo2015). Relatedness refers to a sense of belonging to others, such as feeling cared for, or connected, and a sense of mutual concern. Actions are self-initiated and self-endorsed when they are autonomous (Vansteenkiste et al., Reference Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Sheldon and Deci2004). Autonomy and intrinsic motivation have both been found to have key influences on mental health (Gagné and Deci, Reference Gagné, Deci and Gagné2014). Self-direction and choice are supposed to fuel motivation (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000) and self-efficacy (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986). Relating competency, relatedness, and autonomy to the constructs of positive views of clinical services, perceived need for mental health support, and the actual seeking of clinical support can help target messaging for mental health care.

The perceived need for mental health support is conceptualized as a motivation driven by perceived usefulness of the support; whether one views clinical services positively is conceptualized as a value-driven motivation. Using the components of SDT (see Fig. 1 for the conceptual model utilized), this study reports the prevalence of mental disorders and wellness practices in a sample of Bangladeshi university students and identifies the motivational factors toward self-identification of need for mental health support, positive views of support, and clinical help-seeking.

Fig. 1. Conceptual model based on self-determination theory.

Aims and hypotheses

This study's main aims assess the relationship between autonomy, relatedness, and competency toward using clinical mental health practices (i.e. using professional resources, taking medication) with (1) positive views toward clinical mental health services, (2) perceived need of mental health support, and (3) use of clinical mental health services among Bangladeshi university students. It is hypothesized that greater autonomy, greater relatedness, and greater competency are associated with use of clinical services, positive beliefs toward using clinical services, and perceived need for mental health support.

Methods

Study sample

An online survey was distributed to current Bangladeshi university students aged 18 or older. Faculty from institutions around Bangladesh emailed students to complete the anonymous survey. Invitations were also posted on university Facebook pages. The poll was open for 2 months, from January to February 2020, and the final dataset included 350 student replies.

Survey development

Native Bangla speakers were consulted to analyze the initial English survey and prepare a culturally sound Bangla translation. An interview guide for n = 5 cognitive interviews with the target demographic was created. Participants were asked how they defined mental health and to explain their interpretation of the survey queries during the cognitive interviews. Items that were difficult to understand or culturally unsuitable were altered and pilot tested (n = 10) before final distribution.

Measures

Dependent variables

There were three primary outcomes: clinical mental health practices, perceived need for mental health help, and positive feelings toward mental health. Two items were used to assess current clinical mental health practices: ‘In the past 12 months, have you used medication for a mental health problem’ and ‘In the past 12 months, have you received support (i.e. advice, care) for your mental or emotional health from a mental health professional (i.e. counselor, therapist, psychiatrist)?’ If participants answered yes to either of these questions, they were considered to have utilized clinical mental health services.

To assess the perceived need for mental health support, one yes or no item was asked, ‘In the past 12 months, did you think you needed help for emotional or mental health problems such as feeling sad, anxious, or nervous?’

To assess positive feelings toward using clinical mental health, participants were asked to rate the following two statements on a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree): ‘I feel positive about using clinical mental health services (such as therapy and medication)?’ and ‘I think using clinical mental health services can be helpful for me.’ These items were averaged to measure how positively students felt toward using clinical mental health and dichotomized into high and low scores of positive views toward use.

Independent variables

Scale items are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Relatedness toward using clinical mental health services

Relatedness was measured using two constructs: perceived stigma and proximity to mental health. The 12-item stigma subscale of the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation scale (BACE) was used to assess perceived stigma (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Brohan, Jeffery, Henderson, Hatch and Thornicroft2012) (Cronbach's α = 0.89). In order to assess proximity, the Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS) (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Rose, Little, Flach, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2011) was adapted. Current behavior was assessed using four yes/no questions. To measure whether one spoke to others about mental health, ‘How many people have talked to you about the importance of mental health?’ was asked. The number of people spoken to regarding the importance of mental health was totaled and averaged with the sum of the four yes/no responses to develop a (0–4) scale of mental health proximity. Four items from RIBS measured on a 1–5 Likert scale were used to measure intended conduct toward people with mental health problems. Answers were summed to create a final score (1–20).

Autonomy toward using clinical mental health services

Autonomy was measured using the BACE subscale for instrumental and attitudinal barriers. Participants rated statements about barriers to getting mental health services on a Likert scale, (1) not a barrier to (4) a lot (major barrier). The final result was dichotomized into (0 = )low/neutral or (1 = )high barriers. Four new instrumental barriers related to technology were added to the scale. The revised instrument had a Cronbach's α = 0.85.

Competency in using clinical mental health services

Six items were used from The Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Little, Meltzer, Rose, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2010). Six questions were omitted from usage because they encompassed Western-defined mental disorder symptomology and were not culturally relevant. Questions were rated 0–4 on a scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree. A seventh item, ‘people with mental health problems typically seek help from a mental health professional’, was added to this scale. The scores were summed to create a 0–28 score, with higher values indicating stronger mental health knowledge.

Current nonclinical mental health practices

Measurements of nonclinical approaches to mental health were adapted from the Healthcare for Communities Study and Eisenberg et al.'s (Reference Eisenberg, Hunt, Speer and Zivin2011) research examining mental health service utilization among college students in the United States.

To assess nonclinical mental health support practices, the following questions were asked: In the last year, did you receive mental or emotional health support from (1) friends, (2) family, (3) spouse, (4) religious leader, (5) teacher or coach, (6) other person, (7) social media/technology? Responses were summed, and a variable of 0–8 was created, indicating the number of support sources participants used for nonclinical mental health support.

The Brief COPE survey (Carver, Reference Carver1997) measured students' existing coping strategies. Brief COPE items can be categorized as adaptive coping methods: acceptance, active, altruistic, emotional, informational, planning, positive reframing, and self-care. Responses were categorized into counts (0–8) of adaptive mechanisms used.

A single-item question from the PHQ-9, ‘Have you ever had thoughts that you would be better off dead or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way?’, measured lifetime suicidal ideation.

Covariates

Perceived stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4), established by Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein1983), was used to assess stress (Cronbach's α = 0.70 in current sample). The final score is summed (0–16).

Depression

The PHQ-2 was used to assess depression symptoms (Ganguly et al., Reference Ganguly, Samanta, Roy, Chatterjee, Kaplan and Basu2013). Participants rated feeling depressive symptoms on a scale from 0 (never) to 3 (almost daily). The optimal cut-point for likely having major depressive disorder was 3; thus, depressive symptomatology was divided into high (3+) and low depressive scores in this study (0–2 points).

Demographics

Gender was assessed as male, or female and gender minority. Age was a constant variable. Socioeconomic level growing up was measured as low (never, rarely, or occasionally) or high (most of the time or always) in terms of how often their family had enough money to make ends meet. Sexual orientation was categorized as straight/heterosexual or gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, uncertain, or self-describe. Relationship status was categorical: single, dating, or married; other: divorced, separated, widowed, or self-described. Degree type consisted of Bachelors, Master's, or Doctorate degree. The length of time in university was determined by their year of study (1–4+). Self-perception of religiosity was measured on a 0–10 scale.

Data handling

A validity question was integrated into the survey to ensure participants accurately read questions. All responses from participants who answered the validity question incorrectly were removed from data analysis. Complete case analysis was used for all results.

Statistical analysis

Participants' demographic characteristics, including age, gender, sexual orientation, childhood socioeconomic background, relationship status, year of schooling, degree of study, and university being attended, were reported using descriptive statistics.

A priori α level was set at 0.05. R 2 was reported for the adjusted logistic regression model to explain the total variance. Analyses were conducted using the statistical package SPSS (SPSS 25, 2017). Pearson's correlations and collinearity diagnostics were used to assess possible multicollinearity between independent variables for each model; all value inflation factors were lower than 2, indicating no collinearity. Logistic regression was used to examine the bivariate relationship between independent variables using clinical mental health services and positive views of clinical mental health; odds ratios and p values with confidence intervals are reported. Based on the p values of the unadjusted logistic regression, only variables with p values of 0.20 or less were included in the final regression model (Hosmer et al., Reference Hosmer, Jovanovic and Lemeshow1989). Adjusted odds ratios were reported for the final model, along with model fit statistics. Reliability analysis was also included, using Cronbach's α to report on the reliability of scales used in the study. Two-tailed significance was reported for all analyses.

Results

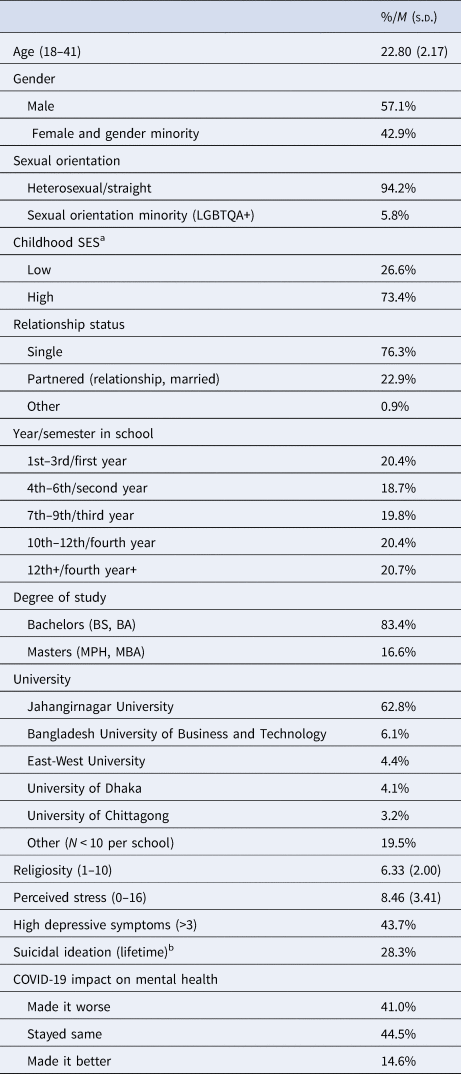

Table 1 shows participant demographics for the total validated, a complete case sample size (n = 350). The overall mean age of the sample was 22.8 years (s.d. 2.17). In total, 57.1% of this sample identified as male, 41.7% as female, and 1.1% of the sample as a gender minority. Most of the sample identified as heterosexual or straight (94.2%), and 73.4% of the sample identified as their families having enough money to make ends meet all or most of the time while growing up. Much of the sample (76.3%) identified as single regarding relationship status. There was near equal distribution of first, second, third, and fourth-year or higher student respondents; 83.4% of the sample were pursuing a bachelor's degree. The sample represented 27 universities across Bangladesh, with the majority (62.8%) from Jahangirnagar University. Students identified as moderately religious (M = 6.33, s.d. = 2.00). Nearly half the sample (49.4%) reported feeling like they struggled with their mental health in the past year, and overall, students were moderately stressed (M = 8.46, s.d. = 3.41). In total, 43.7% of the sample had high depressive symptoms, and 28.3% of the sample had lifetime suicidal ideation. Students had moderate levels of wellness (M = 26.47, s.d. = 10.08).

Table 1. Participant demographics (n = 350)

M, mean; s.d., standard deviation.

a Item asked, how often did your family have enough money to make ends meet growing up, low = never, rarely, sometimes; high = most of the time, always.

b 315 respondents answered this item.

The majority of the sample (70.8%) either felt they needed support for their mental health (49.4%) or had high depressive scores (43.7%) or stress scores (28.0%), or had past suicidal ideation (27.9%). Nearly a quarter of the sample had problems with their mental health, but not perceive they needed help, for example, 76 of the participants (24% of the sample that responded to all pertinent items, n = 315) reported they did not need support for their mental health, while simultaneously reporting high depressive symptoms, stress, or past ideation. For this reason, the regression analysis is conducted on the full sample data, rather than a subsample of only those who reported needing mental health support.

As shown in Table 2, nearly half the population (49.4%) felt they needed help with their mental health. Respondents sought nonclinical support from an average of two sources. On average, participants engaged in five different types of adaptive coping: self-care was used most commonly (80.1%), and two types of maladaptive coping, distraction used most commonly (77.6%). Nearly all participants engaged in at least one mindful activity (96.5%) including identifying and prioritizing values, identifying and trying to change negative thoughts, deep breathing, de-stressing meditation, staying in the moment, focusing on senses, and activities to promote self-esteem.

Table 2. Use of mental health practices and services (n = 350)

M, mean; s.d., standard deviation, higher score equal greater amounts.

a Count of where sought nonclinical support from: friends, family, partner, faith leader, counselor, other person, or technology.

The majority of participants (54.3%) felt positive toward using clinical practices. Only 7.1% received clinical support from a therapist psychiatrist or used mental health medication in the past year.

When examining the construct of relatedness, participants reported low levels of perceived stigma (M = 0.68, s.d. = 0.65). The majority of the sample (78.3%) talked to at least one other person about the importance of mental health. On average, participants knew and spoke to approximately two people regarding the importance of mental health and were moderately willing (M = 12.69, s.d. = 3.99) to interact with someone who has a mental health problem.

When examining the construct of autonomy, only 10.9% of the sample perceived high levels of instrumental and attitudinal barriers to seeking mental health care. Regarding competency, respondents had moderate knowledge regarding mental health (M = 16.00, s.d. = 4.22), indicating they know how to combat mental health problems and correctly identify methods of seeking care and prognoses of mental health treatment.

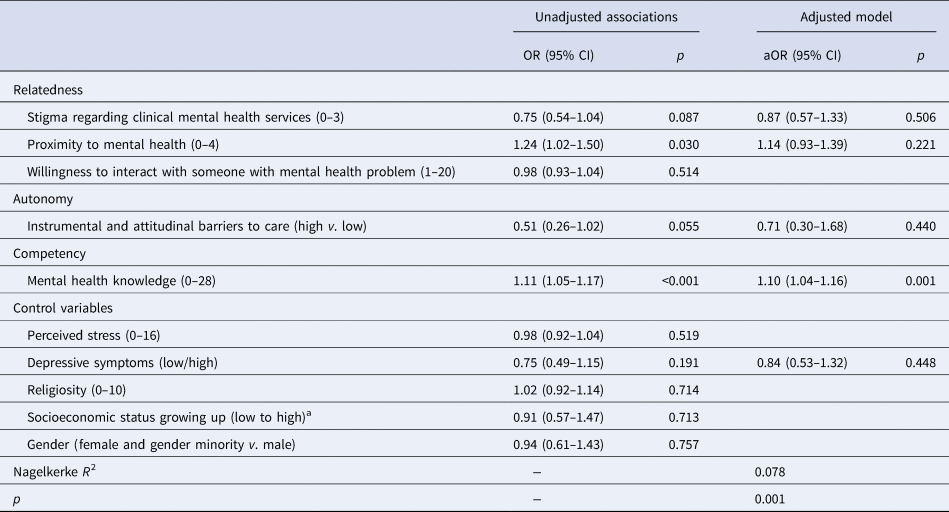

Regression results

Table 3 highlights the logistic regression results for factors predicting positive views regarding clinical health services. In the unadjusted regression, constructs of relatedness and competency were associated with greater positive views of clinical mental health services. Knowing people who have struggled with mental health problems or talking to others about the importance of mental health was associated with having positive views of clinical mental health services. However, in the adjusted model, only competency remained statistically significant (aOR = 1.10, p = 0.001). Having higher mental health knowledge – knowing how to help someone with a mental health problem and having accurate information regarding the efficacy of therapy, medication, and utilization of mental health services – was a significant predictor of having positive views regarding clinical health care. The R 2 for the final adjusted model was 0.078 (p = 0.001).

Table 3. Logistic regression associating self-determination constructs-relatedness, autonomy, and competency with positive v. negative or neutral views of clinical mental health services, N = 350

N , sample size; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval, higher score equal greater amounts.

a Item asked, how often did your family have enough money to make ends meet growing up, low = never, rarely, sometimes; high = most of the time, always.

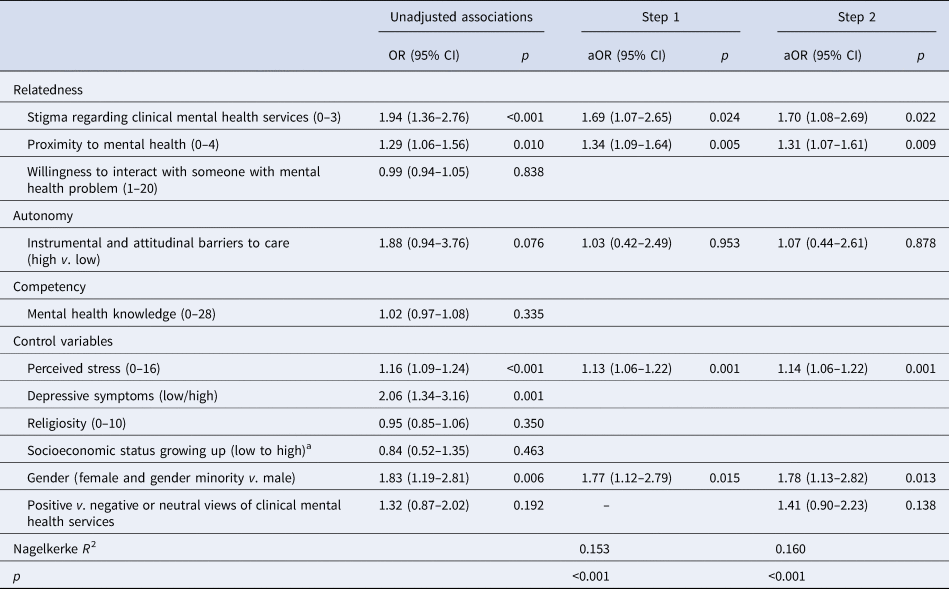

In the second logistic regression model, predictors of whether participants self-identify as needing mental health support are shown in Table 4. In step 2 of the adjusted model, positive views of clinical mental health services are added as a predictor, but there were no changes in significant findings between step 1 and step 2. Relatedness predictors of perceived stigma and proximity to mental health are significant in all models. In both adjusted models, those who perceived more stigma surrounding mental health (aOR 1.70, p = 0.023) and knowing or talking to more people with or about mental health (aOR = 1.31, p = 0.009) had increased odds of self-identifying as needing support for mental health. Females and gender minorities were 78% more likely than males to think they need support for their mental health (p = 0.013). Those with higher scores on perceived stress had greater likelihood of perceiving the need for mental health support (aOR = 1.14, p = 0.001). The R 2 for the final adjusted model is 0.163 (p < 0.001).

Table 4. Logistic regression associating self-determination constructs-relatedness, autonomy, and competency with perceived need for mental health help (N = 350)

N, sample size; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval, higher score equal greater amounts.

Depression was not included in the adjusted model, to address collinearity with perceived stress (r = 0.45), there were no appreciable changes when depression replaced stress in the adjusted model, of the significant findings: stigma aOR = 1.83 (p = 0.008), proximity aOR = 1.33 (p = 0.005), depression aOR = 1.92 (p = 0.005), gender aOR = 2.00 (p = 0.003).

a Item asked, how often did your family have enough money to make ends meet growing up, low = never, rarely, sometimes; high = most of the time, always.

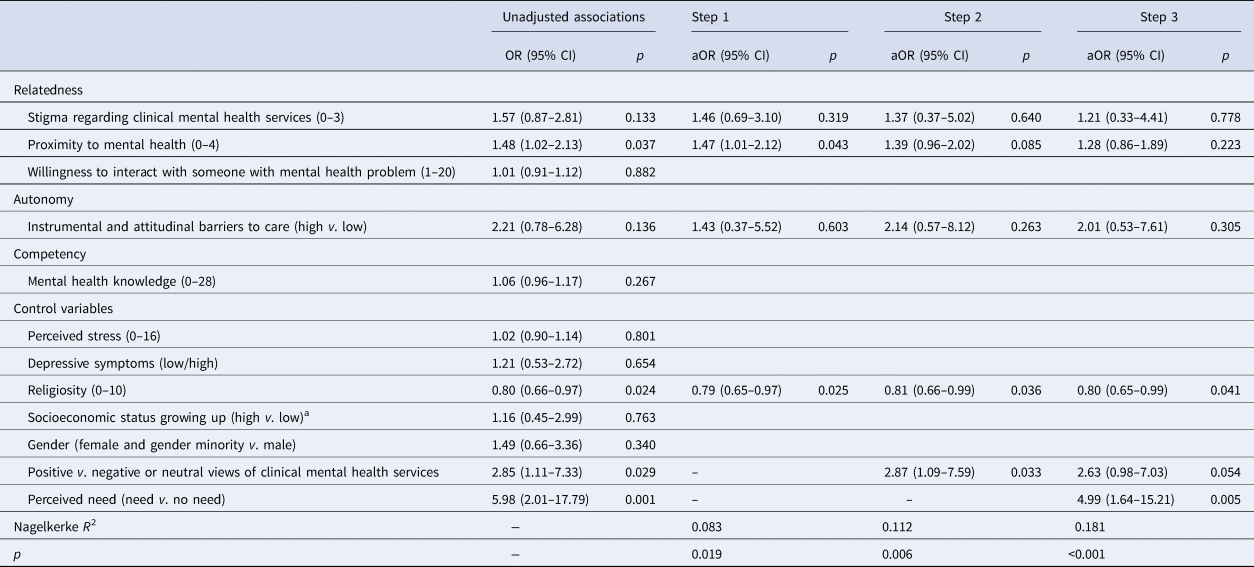

The unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses for the outcome of clinical mental health use are presented in Table 5. The predictors of positive views toward mental health services and perceived need for mental health support were added in a step-wise fashion. In step 1 of the model, those who are more proximal to mental health, for example, knowing more people who may deal with mental health problems, have a higher adjusted odds ratio of receiving clinical health care (aOR = 1.47, p = 0.043). However, this finding did not remain significant when the construct of positive views toward clinical mental health services is added as a covariate, and was found to be significantly associated (aOR = 2.87, p = 0.033) to the outcome in step 2. Once the construct of perceived need is added to the model in step 3, we found that this was the largest driver of clinical service use, as those who perceive help were 400% more likely to receive clinical mental health care. For all steps of the model, higher religiosity levels indicated lower odds of receiving clinical health care (aOR = 0.80, p = 0.041). The R 2 for the final adjusted model was 0.181 (p < 0.001).

Table 5. Logistic regression associating self-determination constructs-relatedness, autonomy, and competency with the use of clinical services, N = 350

N, sample size; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval, higher score equal greater amounts.

a Item asked, how often did your family have enough money to make ends meet growing up, low = never, rarely, sometimes; high = most of the time, always.

Discussion

The prevalence of mental health problems in this sample is similar to other studies in Bangladeshi university populations at a similar period. Depression levels in this sample are high (44%) and comparable to other Bangladeshi student populations (Islam et al., Reference Islam, Sujan, Tasnim, Sikder, Potenza and van Os2020; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Sultana, Hossain, Hasan, Ahmed and Sikder2020; Koly et al., Reference Koly, Abdullah, Shammi, Akter, Hasan, Eaton and Ryan2021). Though only 7.1% of our sample used clinical services, the vast majority (87.1%) sought nonclinical or informal help. Half the sample (50.8%) preferred getting help from their friends or family as opposed to seeking clinical help. This finding is similar to Bilican (Reference Bilican2013) who found that Turkish college students preferred social support over psychotherapy. Over half the sample engaged in about five out of eight adaptive coping strategies; this finding supports other research during the COVID-19 pandemic, where students used a variety of stress-management techniques (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Hossain, Siddique and Jobe2021).

As described by SDT, we hypothesized that autonomy, relatedness, and competency predict perceived need for mental health support, use of nonclinical practices and clinical services, and positive beliefs toward using clinical services; our findings partially confirmed these hypotheses. Perceived need for mental health support and use of clinical services were associated with relatedness characteristics factors, whereas competency was linked to positive views toward clinical mental health care utilization. Higher competency, particularly mental health literacy, can increase positive views of clinical mental health, and higher relatedness can increase ones' perceived need for services. Positive attitudes toward services increase the likelihood of usage, but perceived need is a stronger predictor of utilization. The results provide significant insight into mental health recognition and coping techniques used by Bangladeshi university students.

The findings suggest that positive views of mental health care are driven by competency. This is similar to findings from college populations in the United States, where mental health literacy was found to be a predictor of positive attitudes toward, and actual help-seeking behavior (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Wang, McDermott, Kridel and Rislin2018). Relatedness was indicative of perceived need and use of mental health care. Relatedness factors can increase mental health competency, for example, people who know others with mental health issues are more likely to seek help (Vogel et al., Reference Vogel, Wade, Wester, Larson and Hackler2007; Kearns et al., Reference Kearns, Muldoon, Msetfi and Surgenor2105), because they are more familiar with the topic. While one study in Bangladesh found stigma as a significant barrier to help-seeking (Koly et al., Reference Koly, Abdullah, Shammi, Akter, Hasan, Eaton and Ryan2021), no studies have looked at this as a predictor of perceived need for care. Contrary to our expectations, we found that higher levels of stigma were associated with feeling like one needed mental health help. Perhaps because people who have considered care have also contemplated the alleged effects of the treatment, and thus feel stigmatized by the subject.

While not a main study aim, it was also expected that religiosity would be a protective factor for mental health, as found in other studies based in South Asian countries (Nadeem et al., Reference Nadeem, Ali and Buzdar2017). Devine et al. (Reference Devine, Hinks and Naveed2019) found that having a strong religious identity in Bangladesh was associated with higher wellness. In the current sample, higher religiosity was correlated with higher overall mental wellness (r = 0.24, p < 0.001) and lower perceived stress (r = −0.13, p = 0.016); however, we found higher religiosity levels to be negatively associated with the use of mental health care. This may be due to the use of religiosity or spirituality as a coping mechanism rather than clinical care (Nuri et al., Reference Nuri, Sarker, Ahmed, Hossain, Beiersmann and Jahn2018).

Examining this from a theoretical standpoint, these findings suggest that seeking mental health care stems from internalized motivation. Internalized motivation encompasses doing something because it is useful and aligns with ones' values. Given 70.8% of the sample either felt they could use mental health support or were actually dealing with mental health problems (stress, depression, past suicidal ideation), it is important to look at the entire sample to examine what influences positive views, perceived need, and use of clinical services. We see that knowledge of mental health drives ones' positive views of mental health services, and that higher levels of stress and being close to people with mental health problems is associated with perceived necessity of mental health support, which in turn is the main driver of actually using clinical health services. Future studies should examine internalized motivation as it relates to seeking mental health care. The outcomes of this study were chosen due to how SDT places perceived usefulness (conceptualized as perceived need) and value (positive views of clinical services) driven motivations on a spectrum of motivation. Future directions should establish a time order of motivation and examine pathways from these outcomes of positive feelings toward mental health services, perceived necessity, and engagement in mental health care.

Limitations

The convenience sampling, cross-sectional survey, and self-report nature of the data collection only allow for associations between variables to be examined; it does not allow for broad generalizability time order to be established, and opens the data up for social desirability bias. Given the title of the study, people who were more versed in mental health may have been self-selected, which would cause low levels of perceived stigma and high levels of mental health problems.

Practical implications

Given the use of a culturally adaptive framework and extensive community engagement in the survey development and data collection phases, this study provides culturally competent evidence that emphasizes how crucial it is for Bangladeshi students to identify their mental health care needs. Universities can promote educational campaigns across campus, educating students about the warning signs of deteriorating mental health (Bhuiyan et al., Reference Bhuiyan, Griffiths and Mamun2020); this is particularly important as students have an overall low level of mental health literacy (Arafat et al., Reference Arafat, Al Mamun and Uddin2019). Given that students are open to using adaptive coping strategies, providing students with opportunities to engage in these strategies would be beneficial. As relatedness was associated with acknowledgement of need and actual use of clinical services, and nearly half the sample reports having difficulty with mental health, speaking transparently about the topic could be greatly influential. In short, universities should help students to (a) view mental health positively by increasing their knowledge on the topic, including its prevalence of mental health issues among young adults, (b) provide safe spaces for students to have an open dialogues about mental health in order to help students recognize that they need to seek help as early as possible for better outcomes, and finally (c) provide resources for students to receive care should they seek it. Past research supports these methods, as interventions that provide a space to allow someone who experienced mental health problems to share their stories with college students, and providing education that designs mental illness and stigma are shown to decrease stigma related to mental health (Kosyluck et al., Reference Kosyluk, Al-Khouja, Bink, Buchholz, Ellefson, Fokuo and Corrigan2016). Interviews with students corroborate these findings, and believe that educating students, providing them with resources, and being compassionate and understanding will help decrease barriers to receiving mental health care (Vidourek and Burbage, Reference Vidourek and Burbage2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Jahangirnagar University and Bangladesh University of Business and Technology for allowing the PI to disseminate the study to their students.

Financial support

This study received partial funding from the Department of Behavioral and Community Health at the University of Maryland, School of Public Health, and partial support was provided by Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust (TSET) grant R21-02.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.