Impact statements

This study provides a comprehensive review of workplace mental health promotion interventions for healthcare professionals across Africa. It reveals promising approaches and significant gaps in current research, policy and practice while offering valuable insights that could promote the development of a resilient health workforce through Individual, organizational and policy-level mental health interventions.

Introduction

Health promotion extends beyond individual behaviour change by incorporating social and environmental interventions (World Health Organization, 2024a). The Ottawa Charter emphasizes the implementation of health promotion strategies in various community settings, including workplaces, prisons and schools (World Health Organization, 2024d). The workplace, in particular, offers a unique environment for health promotion due to the substantial amount of time adults spend at work and the diverse range of activities that take place there which can impact overall well-being. Consequently, the Luxembourg Declaration promotes a collaborative effort among employers, employees and society to enhance health and well-being in the workplace through Workplace Health Promotion (WHP) (European Network of Workplace Health Promotion, 2018). WHP involves creating a supportive work environment that promotes healthy behaviours, addresses health risks and enhances physical and mental health and well-being (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024b). While physical health workplace health promotion programs have been more prevalent, recent evidence highlights the importance of mental health workplace health promotion interventions and their impact on employee well-being and organizational performance (Søvold et al., Reference Søvold, Naslund, Kousoulis, Saxena, Qoronfleh, Grobler and Münter2021; World Health Organization, 2024c).

Mental health workplace health promotion focuses on implementing policies, programs and interventions to foster a supportive work environment that enhances employees’ mental well-being. This includes awareness campaigns, stress management programs, work-life balance initiatives and access to mental health services (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Roemer, Kent, Ballard and Goetzel2021; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024a). However, there are disparities in mental health workplace health promotion efforts across countries. Generally, countries in the global North exhibit higher awareness and recognition of mental health issues in the workplace, along with well-established policies, employee wellness programs, mental health training and available support resources. In contrast, countries in the global South face challenges such as limited resources, inadequate infrastructure, cultural barriers, lower awareness, stigma and limited access to mental health services (World Health Organization, 2024b).

The workplace of healthcare workers in Africa is characterized by considerable levels of stress. This stress primarily emanates from factors such as extended working hours, heavy workloads and limited resources (Dubale et al., Reference Dubale, Friedman, Chemali, Denninger, Mehta, Alem, Fricchione, Dossett and Gelaye2019). Consequently, these stressors significantly contribute to the escalation of psychological distress and burnout among healthcare practitioners (Okwaraji and Aguwa, Reference Okwaraji and Aguwa2014; Søvold et al., Reference Søvold, Naslund, Kousoulis, Saxena, Qoronfleh, Grobler and Münter2021). Furthermore, the absence of adequate organizational support and resources specifically allocated to managing mental health exacerbates the aforementioned challenges (Søvold et al., Reference Søvold, Naslund, Kousoulis, Saxena, Qoronfleh, Grobler and Münter2021; Dawood et al., Reference Dawood, Tomita and Ramlall2022). In this regard, healthcare workers are confronted with obstacles that impede their access to care, as the prevailing stigma and discrimination surrounding mental health discourage them from seeking assistance or openly acknowledging their personal struggles (Kapungwe et al., Reference Kapungwe, Cooper, Mwanza, Mwape, Sikwese, Kakuma, Lund and Flisher2010; Egbe et al., Reference Egbe, Brooke-Sumner, Kathree, Selohilwe, Thornicroft and Petersen2014).

Furthermore, healthcare professionals in Africa frequently encounter traumatic experiences within their work environment, including infectious disease outbreaks and humanitarian crises. The exposure to such events heightens the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other related mental health conditions (De Boer et al., Reference De Boer, Lok, Verlaat, Duivenvoorden, Bakker and Smit2011; Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Wessely and Wykes2015). Complicating matters further, the prevailing work-life imbalance and the lack of emphasis on self-care practices serve to amplify these challenges faced by healthcare practitioners (Steele, Reference Steele2020).

To ensure the well-being of healthcare workers in Africa, it is crucial to investigate how to address these pressing mental health concerns through comprehensive interventions that prioritize prevention, early intervention and accessible mental health support services within the workplace. Implementing robust interventions that target the mental well-being of healthcare professionals can foster a resilient and sustainable healthcare workforce, capable of providing optimal care to the population of Africa.

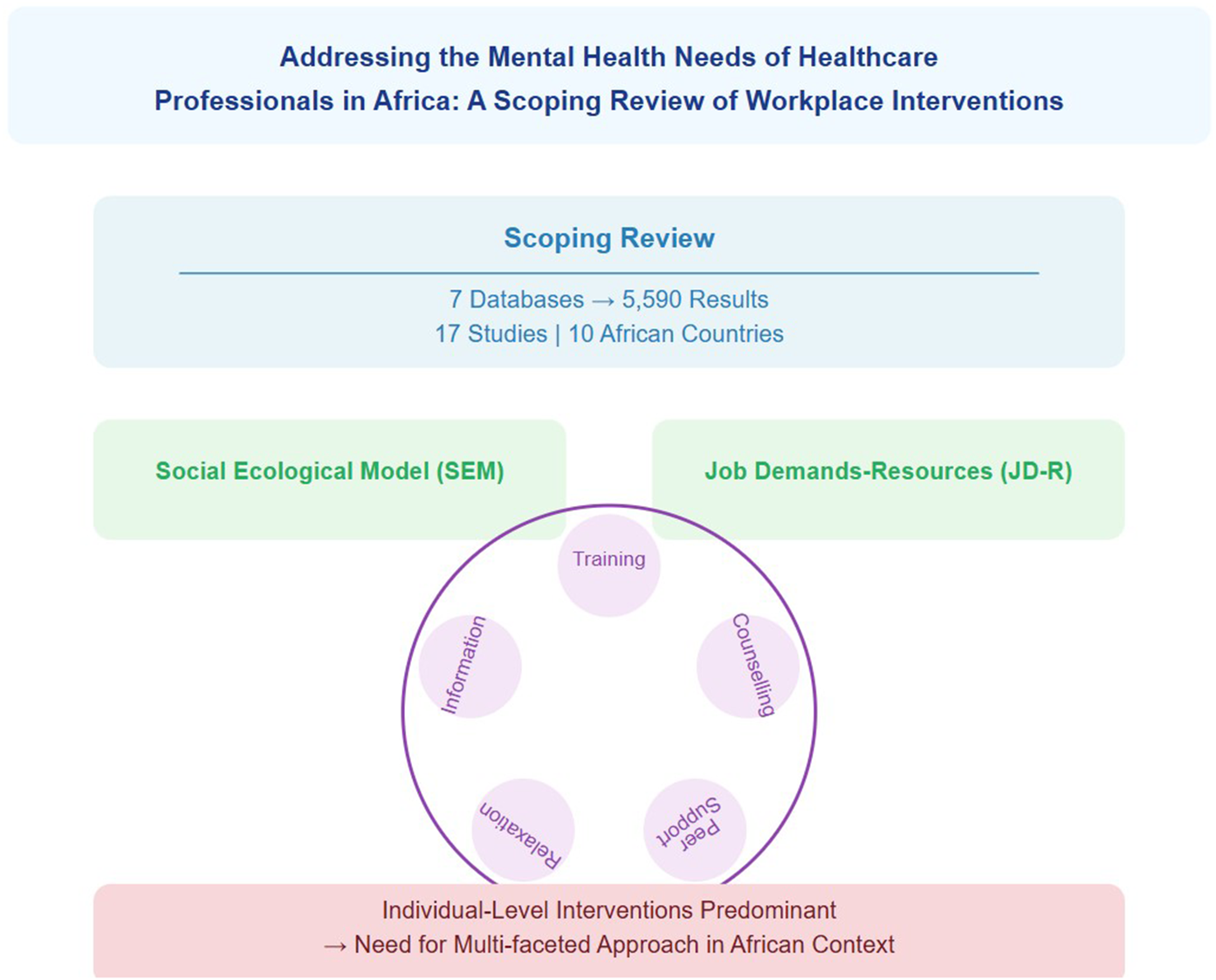

This scoping review aims to identify and synthesize evidence from published and grey literature on mental health promotion interventions designed for African healthcare professionals at their workplaces, encompassing all forms of research and policy documents. Furthermore, we seek to categorize these interventions based on their type, level of implementation (individual, organizational, or policy) and targeted outcomes, thereby providing a comprehensive overview of the current landscape and identifying gaps in research and practice.

Methods

The study adopted the framework outlined by Arksey and Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) for conducting a scoping review (Arksey and O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) This scoping review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).

Theoretical framework

This scoping review is grounded in two interconnected theoretical perspectives: the Social Ecological Model (SEM) (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1979; Mcleroy et al., Reference Mcleroy, Bibeau, Steckler and Glanz1988) and the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Nachreiner, Bakker and Schaufeli2001; Bakker and Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007). The SEM provides an overarching framework, positing that health behaviours and outcomes are influenced by multiple interacting levels: individual, interpersonal, organizational, community and policy. This multi-level perspective aligns with our thematic analysis, which identified interventions targeting various ecological levels. Within this broader ecological structure, the JD-R model offers insight into the specific mechanisms of workplace mental health, proposing that employee wellbeing is determined by the balance between job demands (aspects requiring sustained effort) and job resources (aspects that help achieve goals or reduce demands). Together, these frameworks guide our analysis of workplace mental health promotion interventions for healthcare professionals in Africa, helping to interpret results and inform discussions on practice and research implications. This integrated approach underscores the need for multi-level interventions that address both environmental factors and individual coping strategies, particularly in the resource-constrained and high-demand context of African healthcare settings.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included all articles with primary, secondary and tertiary preventive interventions that promote the mental health of health workers at their workplace in Africa that are written or translated into English. Date of publication, quality of articles and methodology were not considered in the selection. Health promotion interventions that focused only on physical health of health workers at their workplace were excluded. Additionally, studies with interventions to address mental health of health workers in their workplace outside the African continent, and those not available or translated in English were excluded.

Search strategy

Database searches were completed in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycInfo, Cochrane Library (via Wiley), CINAHL, Scopus and Web of Science core collection on the 4th August 2023 to retrieve all relevant literature pertaining to the mental health promotion interventions for healthcare professionals in Africa, relevant keywords, word phrases and controlled vocabulary were carefully selected. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used in each of the databases to combine keywords, and their alternatives with applied wild cards or truncation to search for relevant studies. No language or date limits were applied. Studies were exported to a web-based tool called Covidence (www.covidence.org). Bibliographies from included studies were also reviewed and grey literature was searched on United Nations (UN) agency’s websites such as the World Health Organization (WHO), International Labour Organization (ILO) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). To gather additional information, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) websites such as the African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Africa Mental Health Foundation (AMHF), African Mental Health Research Initiative (AMARI), Strong Minds and Basic Needs Africa were searched. Supplementary Material, Appendix 1 shows full search strategies. All articles from the 7 databases were combined in Covidence and duplicates were removed. The title and abstract were then screened on Covidence by two researchers independently to exclude those that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Where there was disagreement, a third reviewer served as an arbitrator to reach a consensus. After the title and abstract screening, a full-text screening to exclude those that do not meet the criteria was done by two reviewers with a third reviewer involved in resolving disagreements.

Data extraction

Microsoft Excel 365 was used for data extraction and analysis. The collated information includes. Study Title, Authors, Year of Publication, Country, Aim of studies, Workplace of Health Worker, Setting of Intervention, Sample Size, Study Design, Age Range of participants, Category of Healthcare Professionals, Type of intervention, Name of Mental Health Intervention, Description of Mental Health Intervention, Duration of Intervention, Frequency of intervention, Outcomes Measured, Key Findings.

Data synthesis

A narrative approach was utilized to gather identified data. The data were generated based on countries within the African region, specific populations of interest (healthcare workers), the level of healthcare facility as their workplace and the mental health interventions provided. We employed tables to summarize the features of the studies and interventions, and a map to describe the countries where the studies were conducted.

Results

A total of 5590 results were retrieved from databases. No relevant article was found from reference list searching and other websites. A total of 2,925 duplicates were removed and 2665 studies were screened against title and abstract. A total of 2528 studies were excluded after title and abstract while 137 studies assessed for full-text eligibility. After full-text screening, 120 studies were excluded and 17 studies met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 is the PRISMA Diagram while Tables 1 and 2 are the summary characteristics of included studies.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram.

Table 1. Summary characteristics of included studies

Table 2. Summary characteristics of included studies

Countries of study

Seventeen studies that met the inclusion criteria are from 10 African countries, namely Botswana, Egypt, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tunisia and Zimbabwe. Figure 2 shows the map of countries included in the studies with intervention.

Figure 2. Map of countries included in the studies with intervention.

Thematic analysis of included studies

This review identified six key themes highlighting workplace mental health interventions implemented for healthcare professionals in African. These themes reflect the diverse approaches taken to address the mental health needs of healthcare providers across various African contexts.

Training programs

Training programs emerged as the most frequently implemented intervention type (n=8 studies), spanning multiple countries including Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tunisia and Zimbabwe. These programs focused on building critical skills such as stress management (Maingi et al., Reference Maingi, Kathukumi, Jaika, Odera, Konyole and Tibbs2022; Zingela et al., Reference Zingela, van Wyk, Bronkhorst and Groves2022; Kleinau et al., Reference Kleinau, Lamba, Jaskiewicz, Gorentz, Hungerbuehler, Rahimi, Kokota, Maliwichi, Jamu, Zumazuma, Negrão, Mota, Khouri and Kapps2024), assertiveness (Abdelaziz et al., Reference Abdelaziz, Diab, Ouda, Elsharkawy and Abdelkader2020), psychological first aid (Maingi et al., Reference Maingi, Kathukumi, Jaika, Odera, Konyole and Tibbs2022) and self-care(Vesel et al., Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015; Şahin et al., Reference Şahin, Adegbite and Tiryaki Şen2021) .

The majority of studies reported consistent short-term improvements in coping abilities, resilience, wellbeing and lower perceived stress following these training programs (Vesel et al., Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015; Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Hunter, Cole, Evans, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2018; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Uys, Bezuidenhout, Mullane and Bristol2021; Şahin et al., Reference Şahin, Adegbite and Tiryaki Şen2021; Akinsulore et al., Reference Akinsulore, Aloba, Oginni, Oloniniyi, Ibigbami, Seun-Fadipe, Opakunle, Owojuyigbe, Olibamoyo, Mapayi, Okorie and Adewuya2022). For instance, Zingela et al. (Reference Zingela, van Wyk, Bronkhorst and Groves2022) found that their psychological preparedness training in South Africa enhanced healthcare workers’ ability to manage outbreak-related stress and improved coping skills. Similarly, Vesel et al. (Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015) reported improvements in communication, self-care and social connectedness among healthcare workers in Sierra Leone following their intervention.

However, two studies raised important concerns regarding the long-term sustainability of impacts from single-session trainings without follow-up support or reinforcement (Abdelaziz et al., Reference Abdelaziz, Diab, Ouda, Elsharkawy and Abdelkader2020; Kckaou et al., Reference Kckaou, Dhouib, Kotti, Sallemi, Hammami, Masmoudi and Hajjaji2023). This highlights a critical gap in the current approach to training programs and suggests a need for more longitudinal studies to assess the durability of intervention effects.

Counselling services

Counselling services were implemented in four countries—Egypt, Kenya, Sierra Leone and Tunisia (n = 3 studies). These services encompassed individual and group counselling sessions (Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz, Reference Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz2015; Vesel et al., Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015; Kleinau et al., Reference Kleinau, Lamba, Jaskiewicz, Gorentz, Hungerbuehler, Rahimi, Kokota, Maliwichi, Jamu, Zumazuma, Negrão, Mota, Khouri and Kapps2024) and psychological helplines (Abdelghaffar et al., Reference Abdelghaffar, Haloui, Bouchrika, Yaakoubi, Sarhane, Kalai, Siala, Boulehmi, Trabelsi, Bourgou, Charfi, Belhadj and Rafrafi2021).

Studies consistently demonstrated that counselling interventions were significantly associated with reduced stress levels among healthcare workers (Vesel et al., Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015; Abdelaziz et al., Reference Abdelaziz, Diab, Ouda, Elsharkawy and Abdelkader2020; Abdelghaffar et al., Reference Abdelghaffar, Haloui, Bouchrika, Yaakoubi, Sarhane, Kalai, Siala, Boulehmi, Trabelsi, Bourgou, Charfi, Belhadj and Rafrafi2021). For example, Waterman et al. (Reference Waterman, Hunter, Cole, Evans, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2018) found that their phased, CBT-based group program in Sierra Leone effectively reduced mental health symptoms among Ebola Treatment Center staff.

However, Abdelghaffar et al. (Reference Abdelghaffar, Haloui, Bouchrika, Yaakoubi, Sarhane, Kalai, Siala, Boulehmi, Trabelsi, Bourgou, Charfi, Belhadj and Rafrafi2021) noted significant barriers limiting access to these services, particularly the stigma surrounding seeking mental health support. This finding underscores the need for interventions that not only provide counselling services but also address the cultural and social barriers to accessing these services.

Peer support programs

One study based in Sierra Leone evaluated peer support programs involving peer counselling and support groups (Vesel et al., Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015). Vesel et al. (Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015) reported positive impacts on coping skills and interpersonal relationships amongst the participating healthcare workers. While these results are promising, the limited number of studies in this category highlights a need for more research into the effectiveness of peer support interventions in African healthcare settings.

Relaxation techniques

Studies in Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Tunisia (n=3) implemented various relaxation techniques including music therapy (Kacem et al., Reference Kacem, Kahloul, El Arem, Ayachi, Hafsia, Maoua, Ben Othmane, El Maalel, Hmida, Bouallague, Ben Abdessalem, Naija and Mrizek2020), laughter therapy (Hatzipapas et al., Reference Hatzipapas, Visser and van Rensburg2017) and physical exercise (Maingi et al., Reference Maingi, Kathukumi, Jaika, Odera, Konyole and Tibbs2022). These interventions reported positive outcomes, with Kacem et al. (Reference Kacem, Kahloul, El Arem, Ayachi, Hafsia, Maoua, Ben Othmane, El Maalel, Hmida, Bouallague, Ben Abdessalem, Naija and Mrizek2020) finding lower stress and burnout risk from music therapy among operating room staff in Tunisia and Hatzipapas et al. (Reference Hatzipapas, Visser and van Rensburg2017) reporting improved psychological well-being from laughter therapy among community care workers in South Africa.

Interestingly, a Tunisian study by Kckaou et al. (Reference Kckaou, Dhouib, Kotti, Sallemi, Hammami, Masmoudi and Hajjaji2023) explored associations between mindfulness and wellbeing, finding that higher mindfulness was linked to lower perceived stress and greater life satisfaction amongst healthcare workers. This aligns with broader literature on mindfulness being associated with stress and anxiety reduction, suggesting potential benefits of incorporating mindfulness-based interventions in African healthcare settings.

Informational resources

Three studies based in Southern African countries - Botswana, Malawi and South Africa - focused on informational resources (n = 3) encompassing online learning courses (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Uys, Bezuidenhout, Mullane and Bristol2021) and printed guidelines/materials (Akinsulore et al., Reference Akinsulore, Aloba, Oginni, Oloniniyi, Ibigbami, Seun-Fadipe, Opakunle, Owojuyigbe, Olibamoyo, Mapayi, Okorie and Adewuya2022; Zingela et al., Reference Zingela, van Wyk, Bronkhorst and Groves2022). These interventions were associated with increased knowledge, higher confidence, improved resilience (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Uys, Bezuidenhout, Mullane and Bristol2021) and more effective coping skills among healthcare staff (Akinsulore et al., Reference Akinsulore, Aloba, Oginni, Oloniniyi, Ibigbami, Seun-Fadipe, Opakunle, Owojuyigbe, Olibamoyo, Mapayi, Okorie and Adewuya2022; Zingela et al., Reference Zingela, van Wyk, Bronkhorst and Groves2022).

For instance, Kelly et al. (Reference Kelly, Uys, Bezuidenhout, Mullane and Bristol2021) found that their self-paced, online learning course in South Africa led to significant improvements across all measured domains of healthcare worker well-being and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. This suggests that digital interventions could be a promising approach, particularly in contexts where in-person interventions may be challenging to implement

Analysis using social ecological model

Policy level

Only studies from Botswana indicated policy-level interventions (Ledikwe et al., Reference Ledikwe, Grignon, Lebelonyane, Ludick, Matshediso, Sento, Sharma and Semo2014). Ledikwe et al. (Reference Ledikwe, Grignon, Lebelonyane, Ludick, Matshediso, Sento, Sharma and Semo2014) evaluated the national policy of implementing Botswana’s National Workplace Wellness Program (WWP) for healthcare workers across 27 districts. The program targets both physical and mental health, revealing that physical health screenings and promotional activities are more widely adopted than occupational health and psychosocial services. Successful implementation relied on dedicated administrative support and integrating policy activities into the organizational culture, while barriers to implementation included competing work priorities, limited technical capacity for mental health services, stigma and confidentiality concerns.

Organizational level

Studies from Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Kenya and Tunisia indicate organisation-level interventions (Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz, Reference Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz2015; Abdelghaffar et al., Reference Abdelghaffar, Haloui, Bouchrika, Yaakoubi, Sarhane, Kalai, Siala, Boulehmi, Trabelsi, Bourgou, Charfi, Belhadj and Rafrafi2021; Adam et al., Reference Adam, Makobu, Kamiru, Mbugua and Mailu2021; Moyo et al., Reference Moyo, Tshivhase and Azwihangwisi2023). Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz (Reference Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz2015) in a study conducted in Rwanda demonstrated a model for managing Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) among mental health workers through improved staffing, resources, and tools, along with organizational assessments of STS and structured protocols. The Study in Zimbabwe also demonstrated a psychosocially supportive work environment by addressing resource deficiencies and high healthcare costs, allocating adequate financial and human resources and establishing organizational counselling and communication system (Moyo et al., Reference Moyo, Tshivhase and Azwihangwisi2023). Abdelghaffar et al. (Reference Abdelghaffar, Haloui, Bouchrika, Yaakoubi, Sarhane, Kalai, Siala, Boulehmi, Trabelsi, Bourgou, Charfi, Belhadj and Rafrafi2021) highlighted establishment of a Psychological Support Unit (PSU) and a committee to ensure implementation while (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Makobu, Kamiru, Mbugua and Mailu2021) demonstrated a staff well-being initiative involving debriefing sessions to share coping strategies and providing management feedback for organizational adjustments.

Interpersonal and individual level

Studies from Sierra Leone, Kenya and Nigeria demonstrated interpersonal-level intervention (Vesel et al., Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015; Şahin et al., Reference Şahin, Adegbite and Tiryaki Şen2021; Maingi et al., Reference Maingi, Kathukumi, Jaika, Odera, Konyole and Tibbs2022). Specifically, Vesel et al. (Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015) focused on communication skills and social connectedness between colleagues and their clients to reduce stress. Maingi et al. (Reference Maingi, Kathukumi, Jaika, Odera, Konyole and Tibbs2022) focused on maintaining connections with family and trusted friends to reduce fear, isolation and anxiety during health emergencies. Şahin et al. (Reference Şahin, Adegbite and Tiryaki Şen2021) explored the impact of interpersonal levels from both colleagues and family in the form of family-supportive supervisor behaviours (FSSB) from workplace and family conflict, psychological well-being and thriving, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is worth noting that 16 studies included in the review had at least one form of individual-level intervention except the study by Şahin et al. (Reference Şahin, Adegbite and Tiryaki Şen2021) focused only on interpersonal level intervention.

Analysis using the job demands-resources (JD-R) model’s

The Job demands demonstrated by Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz (Reference Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz2015) included client trauma exposure to the 1994 genocide in Rwandaa and high workloads, while Adam et al. (Reference Adam, Makobu, Kamiru, Mbugua and Mailu2021) and Moyo et al. (Reference Moyo, Tshivhase and Azwihangwisi2023) in Zimbabwe and Kenya respectively also reported high workloads, staff shortages and emotional strains. Moyo et al. (Reference Moyo, Tshivhase and Azwihangwisi2023) highlighted insufficient protective equipment and the patient death burden due to Covid-19 while Adam et al. (Reference Adam, Makobu, Kamiru, Mbugua and Mailu2021) indicated financial strain and COVID-19-related fear. The job resourced indicated by Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz (Reference Iyamuremye and Brysiewicz2015) include staff education and therapeutic interventions on secondary traumatic stress (STS). Moyo et al. (Reference Moyo, Tshivhase and Azwihangwisi2023) showed a psychosocial support model for employees and Adam et al. (Reference Adam, Makobu, Kamiru, Mbugua and Mailu2021) indicated resources that include real-time feedback, work schedule adjustments and training. These studies demonstrate the importance of balancing demands and resources to enhance employees’ mental well-being and underscore the effectiveness of the JD-R model in addressing occupational challenges through context-specific resource allocation

Discussion

This scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of workplace mental health promotion interventions for healthcare professionals in Africa. The findings reveal a diverse range of approaches being implemented across the continent, albeit with significant variations in distribution, scale and focus. This discussion will critically examine the key themes that emerged from our analysis, contextualize them within the broader literature and theoretical frameworks, and explore their implications for practice, policy, and future research.

Diversity and distribution of interventions

Our review identified interventions from 10 African countries namely, South Africa, Botswana, Egypt, Malawi, Seirra Leon, Tunisia, Nigeria, Kenya, Rwanda and Zimbabwe. A similar review on mental health workplace intervention in Africa conducted by Hoosain et al. (Reference Hoosain, Mayet-Hoosain and Plastow2023) identified interventions only from 3 African countries (South Africa, Kenya and Botswana). The review by Hoosain et al. (Reference Hoosain, Mayet-Hoosain and Plastow2023) was not limited to health workers. Notably, this review shows an increase in countries within the continent conducting interventions on mental health intervention at the workplace. This increase in the number of countries might be as a result of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health workers. This is because most of the interventions in our review aimed to mitigate the mental health impact of the pandemic on health workers. Nonetheless, the limited and uneven distribution of mental health intervention for workers in Africa likely reflects disparities in research capacity, funding and prioritization of mental health issues across different African nations. The diversity of interventions ranged from individual-level approaches such as training programs, counselling services, and relaxation techniques such as mindfulness, to interpersonal interventions such family supportive intervention, communication and social connectiveness skills to organizational-level initiatives like workplace wellness programs and creating supportive work environment through the provision of work resources to improve employee wellbeing. These interventions are like individual interventions obtained from countries in the global north to improve the mental of health workers (Shiri et al., Reference Shiri, Nikunlaakso and Laitinen2023).

Predominance of individual-level interventions

The majority of interventions identified in this review focused on individual-level approaches, particularly training programs and counseling services. This aligns with the individual level of the Social Ecological Model (SEM) (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1979). While these interventions showed promising short-term outcomes, their long-term effectiveness and sustainability remain weak, as highlighted by studies like Abdelaziz et al. (Reference Abdelaziz, Diab, Ouda, Elsharkawy and Abdelkader2020), Kckaou et al. (Reference Kckaou, Dhouib, Kotti, Sallemi, Hammami, Masmoudi and Hajjaji2023) and Shiri et al. (Reference Shiri, Nikunlaakso and Laitinen2023).

The emphasis on individual-level interventions may reflect the influence of Western psychological approaches and the relative ease of implementing such programs., The focus on individual-level intervention overlooks the critical role of interpersonal, organizational and systemic factors in shaping mental health outcomes. The Studies in Sierra Leone, Kenya and Nigeria highlighted the significance of social connectedness, family-supportive supervisor behaviours and maintaining connections with family and friends for mitigating stress, fear, isolation, anxiety and workplace-family conflict during health emergencies, hence showing evidence of intervention at the interpersonal level of SEM (Vesel et al., Reference Vesel, Waller, Dowden and Fotso2015; Şahin et al., Reference Şahin, Adegbite and Tiryaki Şen2021; Maingi et al., Reference Maingi, Kathukumi, Jaika, Odera, Konyole and Tibbs2022). Evidence from Curtin et al. (Reference Curtin, Richards and Fortune2022) from a systematic review of 121 qualitative studies across 34 countries during several public health emergencies also underscored the importance of interpersonal interventions, with peer support, team cohesion and family connections fostering resilience by providing emotional and practical support.

Limited organizational and policy-level interventions

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model addresses both job demands and resources at an organizational level (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Nachreiner, Bakker and Schaufeli2001) which could potentially yield more sustainable improvements in mental health intervention for health workers at their work place. However, the scarcity of organizational and policy-level interventions identified in our review is a significant finding that contrasts sharply with the wealth of literature emphasizing the critical role of systemic factors in shaping workplace mental health outcomes (LaMontagne et al., Reference LaMontagne, Martin, Page, Reavley, Noblet, Milner, Keegel and Smith2014; Memish et al., Reference Memish, Martin, Bartlett, Dawkins and Sanderson2017). Out of the 17 studies reviewed, only 4 (Ledikwe et al., Reference Ledikwe, Semo, Sebego, Mpho, Mothibedi, Mawandia and O’Malley2017; Abdelghaffar et al., Reference Abdelghaffar, Haloui, Bouchrika, Yaakoubi, Sarhane, Kalai, Siala, Boulehmi, Trabelsi, Bourgou, Charfi, Belhadj and Rafrafi2021; Adam et al., Reference Adam, Makobu, Kamiru, Mbugua and Mailu2021; Moyo et al., Reference Moyo, Tshivhase and Azwihangwisi2023) (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Scarneo and Casa2017; Ledikwe et al., Reference Ledikwe, Semo, Sebego, Mpho, Mothibedi, Mawandia and O’Malley2017; Abdelghaffar et al., Reference Abdelghaffar, Haloui, Bouchrika, Yaakoubi, Sarhane, Kalai, Siala, Boulehmi, Trabelsi, Bourgou, Charfi, Belhadj and Rafrafi2021; Moyo et al., Reference Moyo, Tshivhase and Azwihangwisi2023) explicitly addressed interventions at these macro levels. This gap can be contextualized within broader theoretical frameworks such as the Social Ecological Model (SEM) (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1979) and the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Nachreiner, Bakker and Schaufeli2001), which underscore the importance of the organizational resource to balance the job demands of health workers. Regardless of limited evidence from our review indicating interventions at the organizational level, it reveals that organizational-level interventions, such as a supportive work environment with adequate work equipment, financial and human resources and incorporating psychosocial intervention into the organizational iterative process, are beneficial. Similarly, a comparable review by Shiri et al. (Reference Shiri, Nikunlaakso and Laitinen2023) focusing on countries in the global north also advocates for this degree of intervention. Shiri et al. (Reference Shiri, Nikunlaakso and Laitinen2023) revealed similar barriers to the ones identified from this review in engaging in organizational workplace intervention, Such barriers include insufficient personnel, excessive workloads, time constraints and the scheduling of intervention outside of working hours. The limited focus on these interventions in African healthcare settings contrasts research from high-income countries, where organizational-level interventions have shown effectiveness in reducing occupational stress among healthcare workers (Ruotsalainen et al., Reference Ruotsalainen, Verbeek, Mariné and Serra2015). This dearth of organizational and policy-level interventions may be attributed to various factors, including resource constraints, complex bureaucratic structures and the perceived immediacy of individual-level interventions. However, the few studies that did address organizational levels show promising results, aligning with emerging research on creating "psychologically healthy workplaces (Grawitch et al., Reference Grawitch, Gottschalk and Munz2006).

Cultural adaptation and contextual relevance

The review revealed a concerning lack of explicit discussion around cultural adaptation of interventions. Given the diverse cultural contexts across Africa, the effectiveness of interventions likely depends heavily on their cultural appropriateness and relevance. The Cultural Adaptation Framework (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009) emphasizes the importance of adapting interventions to local contexts, considering elements such as language, metaphors and cultural concepts of mental health (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009).

Future interventions and research should prioritize cultural adaptation, ensuring that mental health promotion strategies resonate with local understandings of wellbeing and align with healthcare workers’ lived experiences in different African contexts.

Emerging innovative approaches

Despite the predominance of traditional approaches, our review identified some innovative interventions that show promise. For instance, the use of digital technologies, such as the chatbot intervention in Malawi (Kleinau et al., Reference Kleinau, Lamba, Jaskiewicz, Gorentz, Hungerbuehler, Rahimi, Kokota, Maliwichi, Jamu, Zumazuma, Negrão, Mota, Khouri and Kapps2024) and the incorporation of indigenous healing practices like laughter therapy in South Africa (Hatzipapas et al., Reference Hatzipapas, Visser and van Rensburg2017), demonstrate creative ways of addressing mental health needs in resource-constrained settings. Specifically, Kleinau et al. indicates the use of chat bots by a healthy workforce for primary and secondary prevention and serves as a source for mental health information. These approaches align with global trends in digital mental health interventions (Torous et al., Reference Torous, Andersson, Bertagnoli, Christensen, Cuijpers, Firth, Haim, Hsin, Hollis, Lewis, Mohr, Pratap, Roux, Sherrill and Arean2019) and the growing recognition of traditional healing practices in mental health care (Uwakwe and Otakpor, Reference Uwakwe and Otakpor2014). However, more research is needed to establish the long-term effectiveness and scalability of these innovative approaches across different African healthcare contexts. Future studies should consider how these interventions can be integrated into existing healthcare systems and adapted to various cultural contexts.

Addressing stigma and barriers to access

Several studies in our review, notably Abdelghaffar et al., highlighted stigma as a significant barrier to accessing mental health support. This finding aligns with the broader literature on mental health stigma in African contexts (Kapungwe et al., Reference Kapungwe, Cooper, Mwanza, Mwape, Sikwese, Kakuma, Lund and Flisher2010; Egbe et al., Reference Egbe, Brooke-Sumner, Kathree, Selohilwe, Thornicroft and Petersen2014) and underscores the need for interventions that not only provide services but also work to destigmatize mental health issues within healthcare settings. Future interventions should consider incorporating anti-stigma components and exploring ways to normalize help-seeking behaviours among healthcare professionals. This could involve awareness campaigns, open dialogues about mental health in the workplace and leadership modelling of supportive behaviours.

Implications for practice, policy and future research

The findings of this scoping review have significant implications for practice, policy and future research in the realm of workplace mental health promotion for healthcare professionals in Africa. In practice, healthcare organizations should prioritize the implementation of multi-level interventions that address both individua, interpersonal and organizational factors, with a strong emphasis on cultural adaptation to ensure relevance and effectiveness. Policymakers need to develop and enforce regulations that support the creation and implementation of workplace mental health interventions in African healthcare settings, including allocating resources for mental health promotion and fostering supportive organizational cultures. Future research should focus on conducting longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impacts of interventions, investigating the effectiveness of organizational and policy-level approaches, exploring the process and impact of cultural adaptation, examining the cost-effectiveness and scalability of different intervention types and investigating integrated approaches that combine multiple intervention strategies. Additionally, there is a pressing need for studies that address the unique contextual factors of African healthcare settings, including resource constraints, cultural diversity and the impact of broader societal challenges on healthcare workers’ mental health. By addressing these areas, researchers can contribute to the development of more effective, sustainable and culturally appropriate mental health promotion strategies for healthcare workers across Africa.

Conclusion

This scoping review has provided a comprehensive overview of workplace mental health promotion interventions for healthcare professionals in Africa, revealing both promising approaches and significant gaps in current research and practice. While individual-level interventions, such as training programs and counselling services, have shown potential for short-term improvements, there is a critical need for more comprehensive, culturally adapted and sustainable approaches that address multiple levels of influence, as suggested by the Social Ecological Model and Job Demands-Resources model. The review has highlighted the scarcity of interpersonal, organizational and policy-level interventions, the limited attention to cultural adaptation and the emerging potential of innovative approaches such as digital interventions. Moving forward, a multi-faceted approach that integrates primary, secondary and tertiary prevention strategies, tailored to the unique cultural and resource contexts of African healthcare settings, is essential. There is also a need for more rigorous experimental, longitudinal and implementation research studies to generate high-quality evidence about intervention effectiveness and long-term impact By addressing the identified barriers, leveraging enablers and pursuing the proposed research directions, we can work towards developing more effective, sustainable and contextually appropriate mental health promotion interventions for healthcare workers across Africa. This not only has the potential to improve the wellbeing of individual healthcare professionals but also to enhance the overall quality and resilience of healthcare systems across the continent, ultimately leading to better health outcomes for both healthcare workers and the populations they serve.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.19.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.19.

Data availability statement

The data that supported the findings are available on the databases used for literature search in the study.

Author contribution

B.I.H. developed the protocol, Screened the articles and developed the first draft of the paper, I.O. Screened the articles, developed the tables, A.O. Screened the articles, A.Y. Screened the articles, J.Y.K. conducted database search, J.F. Screened the articles and developed figures, O.T.M. Screened article, E.E. Screened the articles and gave guidance on thematic analysis and theoretical framework. All the authors reviewed the final draft.

Financial support

The study was not funded by any organization.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.