I. Introduction: More than press releases – a peek behind the curtains of court communication

In times of backlash, the creation of loyalty becomes paramount to any international institution. Loyal state parties remain supportive of an institution even when it comes with financial and reputational costs. They continue to implement judgements and contribute to the budget – or, in the most extreme cases, fend of attacks to delegitimize or curb the authority of a court together with loyal non-state actors.Footnote 1 According to Albert O. Hirschman’s classic theory, it is particularly the factor of loyalty that affects whether a state chooses between voicing its criticism or exiting the institution altogether. In his words, ‘loyalty holds exit at bay and activates voice’.Footnote 2

Loyalty represents the continued commitment to an institution even in the face of challenges.Footnote 3 It is a form of diffuse support,Footnote 4 which contains a ‘reservoir of favorable attitudes or good will that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed or the effects of which they see as damaging to their wants’.Footnote 5 Loyalty, in this sense, is an indispensable resource for an institution at any time. However, in times of open contestation and during reform processes, a high degree of loyalty by core constituents is crucial for the mere survival of an institution. Against this background, the crucial question remains: How does an institution create loyalty?

This article investigates how the European and the Inter-American human rights regimes have developed communication practices to create loyalty over the last decade. In recent years, both regimes have undergone significant reform processes prompted by outspoken state criticism.Footnote 6 This criticism concerned, on the one hand, the massive backlog in cases and individual applications pending before the European and Inter-American human rights organs, and, on the other, the level of domestic interference of human rights bodies. The proposed changes were thus aimed at strengthening institutional efficiency and increasing elements of subsidiarity. Yet, in the shadow of official reforms – such as the Interlaken Process of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)Footnote 7 and the ‘Strengthening Process’ of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR)Footnote 8 – the reform of communication and outreach practices has been subtler but no less transformative. In the midst of this reform, new institutional actors have risen to prominence: communication departments and communication professionals.

Their ascent signifies a transformation in how international courts relate to the public, thereby squashing the traditional conceptualization of judgments and judges as the exclusive vehicle of court communication.Footnote 9 Today, communication departments exercise essential institutional functions on a daily basis: they inform the public about judgments and decisions; they educate on the institution’s mission; they tout the successes and create awareness of the challenges faced by the institution. They frame how the institution is portrayed, thus highlighting its value and importance to different stakeholders, but also strategically legitimize the institutional activities among the general public. By relying on interviews with communication officials of core departments of the European and the Inter-American human rights regime, this article traces the move from the traditional mode of one-way communication via press releases to the development of modern, multifaceted and interconnected two-way communication strategies. The latter goes hand in hand with the professionalization of communication officials, the enlargement of audiences and activation of communities of practice, and the development of new instruments – in particular, social media and visual formats.

The empirical analysis of the communication practices of the European and the Inter-American human rights regimes aims to contribute to the research in three respects. First, it analyses, for the first time, how the ECtHR and the Inter-American Human Rights Court (IACtHR) communicate, thereby complementing studies on the communication practices of domestic,Footnote 10 regionalFootnote 11 and international courts.Footnote 12 In contrast to most empirical studies on judicial communication, which have focused on single instruments such as press releasesFootnote 13 or social media,Footnote 14 it analyses the development of communication instruments holistically. Second, it tests the theoretical framework of communication practices as tools for the strategic legitimation of international institutionsFootnote 15 by going above the micro-level of court communications. In both regimes, the life-cycle of human rights judgments extends beyond the press department of the courts. In the European system, judgments are also communicated by the Council of Europe (CoE) and their implementation is monitored by a special department to the Committee of Ministers (CM). The Inter-American system closely links the Court to the IACHR, which is monitoring situations, rendering individual decisions and funnelling cases to the Court. The insights of this article are based upon interviews conducted with experts from all aforementioned bodies to analyse those communication practices comprehensively. Third, by building on the insights of communication ‘insiders’, the article sheds light upon communication professionals as hidden or ‘unseen actors’ of international courts.Footnote 16 Empirical studies of communication practices of courts have focused primarily on judges and their participation in public debate.Footnote 17 The role, contribution and importance of communication professionals to the judicial and quasi-judicial bodies have so far been neglected in scholarship.Footnote 18 In contrast to the media activities of judges,Footnote 19 the strategies of communication officials have so far not triggered significant public or institutional scrutiny, even though they might frame the public image of an institution more permanently. This is surprising given that empirical studies have demonstrated the importance of institutional bureaucracies,Footnote 20 such as strong secretariats, for the survival of an institution.Footnote 21

This article is divided into four sections. First, I will expound on the concept of institutional loyalty (section II). I will then illustrate the underlying mechanisms of institutional communication practices (section III) before comparatively analysing the practice of communication in the European and Inter-American human rights regimes over the last decade (section IV). Ultimately, I argue that communication practices are an essential instrument for ensuring the resilience of the European and Inter-American human rights regime, in particular in times of increasing contestation and state backlash (section V).Footnote 22

II. Loyalty

Loyalty matters. As state parties are increasingly re-evaluating their commitment to institutional membership, I argue that we should turn our attention to the concept of institutional loyalty. The concept of loyalty is a fuzzy one. Philosophers, psychologists, economists, sociologists and religious scholars have long disagreed on the nature and definition of loyalty,Footnote 23 but share the understanding that loyalty is an inherently natural element to human life. It can be defined as ‘a practical disposition to persist in an intrinsically valued (though not necessarily valuable) associational attachment, where that involves a potentially costly commitment to secure or at least not to jeopardize the interests or well-being of the object of loyalty’.Footnote 24 In legal-institutionalist scholarship, the dynamics of loyalty have often been overshadowed by the voice-exit equilibrium.Footnote 25 In the following section, I will first develop a definition of institutional loyalty and, in a second step, analyse how communication can act as an instrument for international courts to generate institutional loyalty.

Defining institutional loyalty

I posit that the concept of loyalty is the starting point for a deeper analysis of instruments, which an institution might deploy to counteract state backlash. Loyalty becomes apparent in a situation of institutional conflict or crisis when an institution faces heightened politicization and criticism in mass media. I argue that loyalty is a particularly helpful concept to understand why state parties, who are critical of an institution, not only refuse to leave the institution but might even be actively involved in its reform. Since the concept is under-developed in institutionalist scholarship, I will give it clearer contours by relying on a classic piece of scholarship: Albert O. Hirschman’s Exit, Voice, Loyalty.

According to Hirschman, institutional loyalty emerges out of the combination of exit and voice options. However, he does not offer a deeper analysis of loyalty’s underlying mechanisms. For him, loyalty remains primarily an intervening factor, which reduces the likelihood of exit and exacerbates the importance of voice. It is the main explanation of why critical state parties not only refuse to leave the institution, but might even become actively involved in reforming it. It can be defined as ‘a special attachment to an organization’,Footnote 26 which impedes members from leaving an institution so ‘they will stay on longer than they would ordinarily, in the hope, or rather, reasoned expectation that improvement or reform can be achieved “from within”’.Footnote 27

This special attachment to an institution can also be understood as a type of diffuse support, a concept that has a long pedigree in systems theory. While David Easton refrains from using the word ‘loyalty’, he characterizes diffuse support in similar terms as a ‘form of a generalized attachment’ to the idea or representation of what an institution is, not what it does.Footnote 28 Diffuse support derives from socialization or direct engagement with the institution over a long period of time.Footnote 29 In contrast to specific support, diffuse support is unrelated to specific outputs or performances of the institution. ‘Whereas specific support is extended only to the incumbent authorities, diffuse support is directed towards offices themselves as well as towards their individual occupants. More than that, diffuse support is support that underlies the regime as a whole and the political community.’Footnote 30 Like Hirschman’s concept of loyalty, the existence of diffuse support explains the continued membership of a state in an institution despite difficult circumstances; it is a ‘reservoir of favourable attitudes or good will that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed or the effects of which they see as damaging to their wants’.Footnote 31 While there is significant overlap of both concepts, diffuse support remains focused on broad, encompassing positive attitudes among the general population. The concept of loyalty as understood by Hirschman, however, focuses on the moment of crisis. It can also be applied only to particular segments of the political community. For instance, even when there is not sufficient diffuse support among the general public, the existence of loyalty towards the institution among a small number of stakeholders might prevent the exit of a state. Hence, the two concepts are not mutually contingent and loyalty holds more potential to uncover the multi-level and multi-stakeholder social environment of international institutions.

Compliance is not an essential factor to account for the existence of loyalty. While a positive belief system on the value of an institution certainly facilitates compliant behaviour, neither Hirschman nor Easton considers it relevant to account for the degree of loyalty as diffuse support. At least theoretically, the decision to obey an institution ‘is conceptually independent of whether an institution is judged to have the authority to make a decision’.Footnote 32 Compliant behaviour might be an indicator of loyalty, but in order to understand whether compliance, or non-compliance for that case, is motivated by loyalty, appropriate contextual information is required. According to Easton, ‘not all compliance need reflect supportive sentiments; not all violations of rules need be non-supportive. A number of permutations and combinations is possible.’Footnote 33 Shifting the focus from the artificial binary distinction of compliance versus non-compliance to the dynamics of loyalty creation allows us to identify the critical junctures in the relationship between state parties and institutions.

For many institutionalist scholars, the concept of loyalty is heavily intertwined with the idea of legitimacy, in particular sociological legitimacy.Footnote 34 This source of legitimacy, also called popular or public legitimacy, differs from traditional normative accounts of legitimacy as its primary reference is the social group. While the former considers the exercise of authority legitimate as long it can be normatively justified, the latter argues that ‘a court enjoys institutional legitimacy as long as the public awards it support over a relatively long period of time’.Footnote 35 It describes ‘the beliefs among the mass public that an international court has the right to exercise authority in a certain domain’.Footnote 36 This shift, from traditional forms of legitimacy to sociological legitimacy, was most prominently studied at the US Supreme Court,Footnote 37 but is increasingly also observed in studies of international courts.Footnote 38 Most importantly, the scholarship on sociological legitimacy has highlighted how strategies of legitimation are able to connect the institutions with those various audiences.Footnote 39 Legitimation practices are thus employed by an institution to reconstruct the purpose of the institution, to explain and justify its actions, and to emphasize its contribution.Footnote 40 Loyalty should thus not be understood in contrast to the study of legitimacy of international courts, but rather as an expansion of it.

The main merit of using the concept of loyalty for the study of international courts lies in its interrelational character. It builds on the insights derived from legitimacy research and takes loyalty as a starting point to shift the focus of investigation. Instead of asking unilateral questions such as ‘Does this institution enjoy legitimacy?’ or ‘Do you consider judgment X legitimate?’, loyalty poses reciprocal questions with at least two relevant actors, namely ‘Who can be loyal, and to whom?’Footnote 41 Loyalty, in this sense, helps to understand relationships between two actors. For the subject of loyalty, a variety of actors comes to mind. For international courts, one could consider state parties, but also domestic compliance partners such as bar associations, judges, and civil society. All those actors can be loyal to an international court and express this loyalty in a variety of ways: states can directly implement judgments, domestic judges can integrate the jurisprudence of international courts, while civil society, academics, journalists, human rights defenders and the general public can disseminate judgments in the national sphere, pressure state authorities to comply with them and defend the international courts against populist attacks.

This also means that, in contrast to legitimacy, the object of loyalty must be material. One can be loyal towards an individual, a community, a state or an organization, but not to ideas. Of course, the relational character of loyalty does not mean that those material objects are unconnected to underlying sentiments – or, as Lauge N. Skovgaard Poulsen highlights:

Loyalty to a state or an ally, for instance, will often be partially rooted in the ideas or principles that state or ally signify. Clearly, ideas and principles shape and interact with inter-relational loyalty, but the basic building block for loyalty ties remains two actors in a relationship with each other.Footnote 42

The interrelational character also necessitates interactive practices. This means that legitimation practices from the institution vis-à-vis external actors depict only one side for the creation of loyalty, namely how the institution aims to create a positive image among its constituents. Practices for creating, maintaining or regaining of loyalty (loyalitification), on the other hand, also include how those constituents react to the institution, irrespective of whether those are state or non-state actors.Footnote 43 So how does an international court create loyalty?

Creating institutional loyalty

The mechanisms through which institutional loyalty is generated are complex and require further exploration. Most importantly, since Hirschman and Easton published their work, the public sphere in which international institutions are embedded has changed considerably. In the contemporary information age, media outlets and communication channels have multiplied and now dominate the public sphere.Footnote 44 Whereas the prestige of the institution and the state’s length of membership might have been sufficient for loyalty previously, states are now more openly questioning their commitments. In this situation, it is paramount to shift away from solely attempting to generate loyalty at the state level and to create loyalty within society. A prerequisite condition to create this kind of loyalty and form a positive belief system is information about the court and its activities. A positive view of an institution in public opinion might deter state authorities from openly attacking the institution, but is of little use when the relevant domestic compliance partners are not actively pressuring state authorities to remain committed to the institution.Footnote 45 From the research on domestic and international courts, a two-step approach for the creation of institutional loyalty can be deduced: first, the generation of awareness about the existence of the court among the general public; and second, the establishment of communities of practice around the court through mutual, active engagement.

For a long time, international courts were far removed from the domestic public discourse. Like Sleeping Beauty,Footnote 46 they were based in faraway lands, guarded by procedural requirements, and showed almost no significant activity. Hence, as a first step to creating loyalty, a court needs to foster societal awareness about the institution by informing the general public about its mandate and relevance. The assumption is that a positive view about the court in domestic public opinion poses a major hurdle for de-legitimation discourses by critical non-state actors or state authorities’ attempts to withdraw from the institutions – that is, it ensures that states remain loyal. In contrast, if the public is unaware of the existence of the court, this facilitates governments leaving or undermining it. The knowledge about international courts has changed considerably over the last two decades as the increasing proliferation of international courtsFootnote 47 and the judicialization of mega-political issuesFootnote 48 have put the activities of international courts on the front pages of mass media all over the world. While this has raised their profile among the general public, they only have limited capacity to actively influence public opinion.Footnote 49 Indeed, their counter-majoritarian nature makes them especially susceptible to populist mobilization narratives against them.Footnote 50

This is why, in a second step towards generating loyalty, international courts have turned toward their core constituents. Courts not only need the general public to be aware of their existence; they also require active supporters who bolster their activities and call for state parties to uphold their commitments such as domestic judges, human rights lawyers and civil society. Very often, those supporters can be found in the epistemic communities surrounding the court.Footnote 51 Throughout the last decades, those communities have not only grown significantly in size, but have also become more diverse. They are embedded in complex informal institutional ecosystems, which are not necessarily unified in their approach towards the institution.Footnote 52

In particular for human rights courts, enjoying popular legitimacy among domestic political elites and legal actors such as judges, bar associations, human rights lawyers, journalists and civil society is crucial.Footnote 53 While scholars have usually studied the influence of those actors as compliance constituents,Footnote 54 their real impact goes far beyond the implementation of judgments. In the best case, they can form a community of practiceFootnote 55 that is united through ‘common practices as well as a shared understanding of the social meaning of those practices’.Footnote 56 Armin von Bogdandy and Rene Urueña have applied this concept to account for the strong Latin human rights community that was formed around the Inter-American human rights regime.Footnote 57 This community then acts as a bulwark against backlash and defends the IACtHR against heavy criticism and any attempts to undermine it.Footnote 58 In the vocabulary of Hirschman, the loyalty exhibited by communities of practice can reduce state exitFootnote 59 as well as hinder attempts to curtail institutional competencies via reform processes.Footnote 60 This leaves the question of how to build such loyal communities. By putting shared practices at the centre of a community, von Bogdandy and Urueña shift the focus from a transactional concept of mutual influence of courts and public opinion to an interactional one involving a variety of core constituents. Shared practices require the active interaction of courts with state authorities and non-state actors.Footnote 61 It requires courts to reach out and actively engage with their constituents.

This article investigates how communication practices can generate both awareness among the general public and interaction with communities of practice – and thus, ultimately, loyalty. But why did institutional communication practices become so important in recent decades?

III. Communication

The active employment of communication practices is key for the creation of loyalty. Throughout the last decade, international courts have developed a wide range of communication strategies and instruments, which will be traced in the following chapter. First, I will illustrate the shift in institutional communication by international courts from passive accessibility to active self-legitimation. Second, I will demonstrate how and why communication practices became an indispensable organizational resource in times of backlash, as they allow for mutual interaction.

Moving from accessibility to loyalty creation

International institutions have for a long time employed strategies of public diplomacyFootnote 62 – that is, activities that aim at ‘promoting better understanding and sustainable relationship with target audiences’ both inside and outside the institution.Footnote 63 For international courts, concerns of neutrality, impartiality and the authority of the office make them more sceptical towards openly embracing those instruments. Yet international courts have always engaged in outreach strategies, in particular the off-the-bench activities of international judges.Footnote 64 In both the European and Inter-American human rights regime, institutional actors engage in training and coordination programs with domestic partners from state authorities, legal practice, education and academia.Footnote 65 They also have long-standing internship and visiting programs, and facilitate a cross-regional human rights network – for instance, through the annual regional human rights courts meeting.Footnote 66 All these activities also serve to improve the sociological legitimacy of the court. This does not mean that they are always successful in doing so – on the contrary, those activities can be highly controversial, such as when ECtHR President Robert Spano visited Turkey in September 2020 and accepted an honorary degree from Istanbul University.Footnote 67

Among those manifold instruments of public diplomacy, the communication activities of international courts have not yet attracted much scholarly attention. In contrast to the public and media activity of international judges, the communication of international courts is usually neither regulated nor scrutinized. This can be explained by the traditional perception of communication as a mere instrument of accessibility to the public. For most scholars and practitioners of international courts, the communication of international courts is traditionally embedded in the idea of transparency and the open court principle.Footnote 68 Even though specific arbitration proceedings are infamously closed, most international courts feature public hearings that allow for either direct physical access or indirect mediated access through the invitation of the press, the hosting of live streams and so on.Footnote 69 However, this is only a fraction of the institutional communication in which international courts engage.

While strategies of public diplomacy have long been a staple of international institutions, the use of professional communication is a more recent phenomenon. It is in line with a general transformation of the public sphere, in which communication became an essential resource of power. The media democracy, which Jürgen Habermas had already described in the early 1960s, combined with the massive surge of digitalization, has accelerated the information flows to an unprecedented level in the last decade. Crucially, those information flows are not a one-way street but come from both directions. This emphasizes the essential need for mediated political information, and consequently institutions to adopt professional communication practices that can formulate targeted information and remain responsive.Footnote 70 Only those are able to generate a feedback loop between an informed elite discourse and a responsive civil society. This signifies an evolution from public diplomacy as an instrument of strategic legitimation to the implementation of communication practices for loyalty creation.

Nowadays, international courts are employing multiple communication strategies to interact with the public.Footnote 71 They have full-time press officers, who craft media statements, provide summaries, are active on social media and give interviews to the press. Similar to international institutions,Footnote 72 they have slowly but significantly developed their communication capacities, thus shifting from a passive approach to accessibility to active management of communication instruments. This does not necessarily mean a quantitative increase in the output of court communication.Footnote 73 Political science research has demonstrated that institutions increasingly use communication as an instrument to strategically legitimatize themselves. They thereby create an ‘interactive political process … to establish and maintain a reliable basis of diffuse support for a political regime by its social constituencies’.Footnote 74 This development implies a shift from the relatively passive provision of transparency and public access to international decision-making to international institutions becoming active interlocutors in public debate. Interestingly, it is not the judges, or even the President, who officially represents the court in public,Footnote 75 but rather bureaucratic actors who have spearheaded and were empowered by this process.

Communication practices in times of backlash

Naturally, communication activities are not the only instrument available to human rights courts and commissions to generate loyalty in times of backlash. Scholars have highlighted, among other things, the importance of well-reasoned judgments,Footnote 76 transparency in the election of judges and commissionersFootnote 77 and the participation of non-state actors.Footnote 78 While those are valuable strategies, their implementation requires significant political commitment over a long period of time to change public opinion. Communication instruments, however, can quickly extinguish a (metaphorical) fire before it triggers a full-blown backlash and neither require massive institutional changes nor treaty-based amendments. It is therefore not surprising that communication practices have been expanded.

The politicization of international institutions in recent years further fuelled the evolution and expansion of communication activities and the professionalization of communication departments.Footnote 79 In an empirical study of 48 international organizations from 1950 to 2015, Matthias Ecker-Erhardt found that rising scrutiny of international institutions by transnational civil society is the causal factor for the strengthening of capacities:Footnote 80

Legitimacy concerns helped drive IOs to develop their public-communication capacities. Growing politicization means that IOs face an increasing need to justify their behaviour, particularly in the face of protests or scandals. In response, IOs reformed their public communication as a means to more effectively manage their image with stakeholders and the general public.Footnote 81

In a situation of backlash:

International institutions themselves are taking an increasing interest in the management of their legitimacy. They employ legitimation strategies, including communication and symbolic policies as well as institutional and organizational reforms, to convince different ‘social constituenc[ies] of legitimation’ of their right to rule.Footnote 82

International courts exhibit similar developments to those observed in international organizations. As they face a significant amount of politicization – even a full-blown backlash in some cases – their increasing need for self-legitimation is reflected in their communication practices. It is obvious, even for non-experts, that international courts today do more than issue press releases. They have opened up to the public by enabling live streams, publishing judgments instantly on an accessible online platform and even featuring various social media accounts, mainly on Twitter and Facebook.Footnote 83

Against this background, I argue that the function of international courts’ adoption of communication practices is not only self-legitimation but also loyalty creation. This explains their development from instruments of one-way communication to two-way communication that allows for mutual interaction. For instance, Jane Johnston’s research on domestic courts in the United States and Australia has demonstrated that two-way communication interfaces such as social media are particularly useful to engage with communities of practice.Footnote 84 As analysed by Pablo Barberá et al., the courts’ adoption of social media communication follows a double-pronged legitimation strategy.Footnote 85 On the one hand, international courts attempt to gain more legitimacy by informing the general public about the work and mission of the courts, thus counteracting the lack of knowledge or general awareness of its existence or activities; on the other hand, international courts also strive to counteract the de-legitimation strategies and misinformation circulated by populist and other political actors.

By actively pursuing public communication, international institutions can thus take active charge of their public image and respond to their critics. This proactive communication policy empowers the institution to promote a carefully crafted public image even at the expense of silencing critical voices.Footnote 86 Communication practices must thus not be understood as purely informative messages; instead, they are instruments to monitor, reframe and influence the public debate to create loyalty among its constituents. By adopting a variety of media instruments, international institutions participate in the ‘market for loyalty’, which means they strategically create narratives of social cohesion and identity to attract potential ‘buyers’, namely ‘the citizens, subjects, nationals, consumers-recipients of the packages of information, propaganda, advertisements, drama, and news propounded by the media’.Footnote 87 To stay with the market analogy of Monroe Price, the ‘buyers’ pay for this transaction with a variety of immaterial activities – for instance, being obedient vis-à-vis the institution or defending it against the pushback of others. Communication, in this sense, is an instrument to strengthen the ties between the institution and the respective audiences in the hope that those audiences will support the institution in conducting its mission, collaborating in its activities and rallying to its defence in times of backlash.

IV. The European and Inter-American human rights regimes

The European and the Inter-American human rights regime faced an unprecedented level of politicization in the last decade. Both regional human rights courts and the Inter-American Commission were targeted by these debates, which unsurprisingly led to a series of reform processes. In some instances, the situation even escalated to outright state backlash – that is, attempts to undermine the authority of the institution.Footnote 88 In this context, loyal communities of practice that came to the defence of the court became paramount. Accordingly, this article assumes that the challenges faced by both regimes throughout the last decade have also influenced their modes of institutional communication.

In the following section, I will investigate the practice of the European and Inter-American human rights regimes in order to assess whether the insights derived from the communication practices of international organizations can be transposed to the judicial and quasi-judicial bodies of both regimes. In order to create loyalty, both regimes would have needed to professionalize their communication actors, as well as pursue communication strategies that can create awareness among the general public and activate communities of practice.

Research design and methodological remarks

This article adopts an internal perspective on the study of communication practices of both regimes. This means that, instead of analysing the external output of communication practices such as press releases or social media activity, I will focus on highlighting the role of communication officials. By using a qualitative approach, I can identify the underlying rationales and motives that led to the transformation of communication practices in both regimes over the last decade. As communication strategies are not disclosed to the public, interviews with key officials promised to be the most instructive method. This also allowed a comprehensive analysis of communication instruments as opposed to an exclusionary focus on a single instrument. Instead, the focus shifted towards identifying general trends in communication strategies featuring a wide range of instruments; after all, only those have the potential to create long-lasting loyalty among state and non-state actors. However, this research design necessarily limits the results of the empirical study. It is therefore not the purpose of this study to conclusively verify the effectiveness of communication practices.

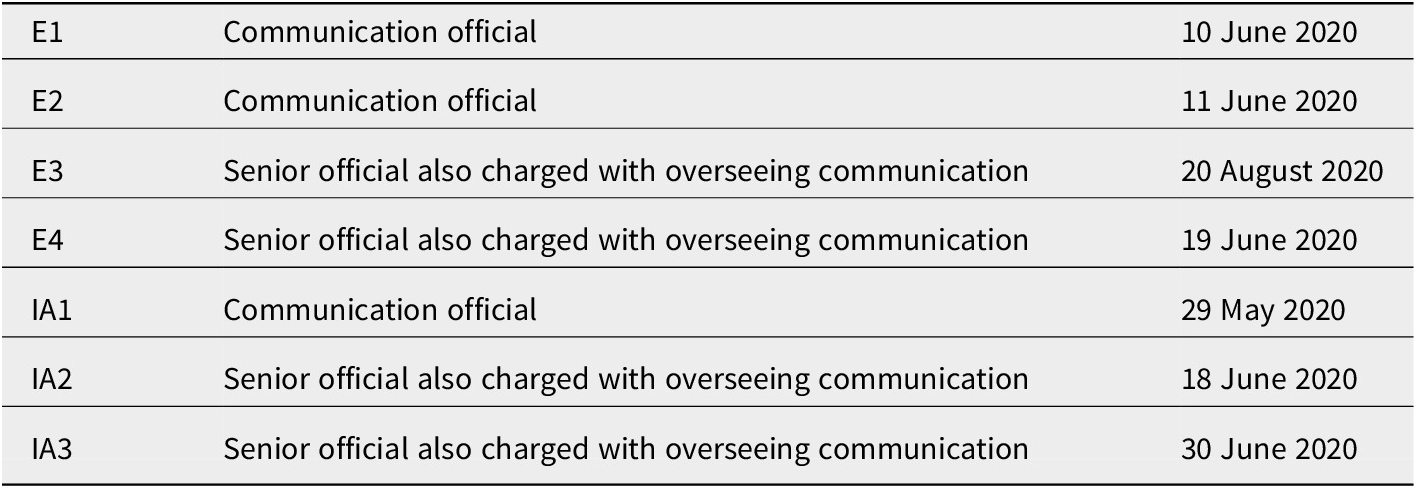

The empirical insights of this article are based on seven semi-structured interviews with full-time communication officials of the European and Inter-American human rights bodies, which were conducted between April and August 2020. Due to the pandemic, the interviews took place via phone (two) and video technology (five); the latter enabled a verbatim transcription. The interviewees were selected based on their specific job descriptions as mid- and high-level communication officials.Footnote 89 The group of interviewees included officials from the two courts, as well as the IACHR, the Department of Execution at the CM and the CoE. This was necessary due to the strong inter-institutional linkages and workflows between the courts and other institutional bodies. However, to keep the focus on whether communication can create loyalty for international courts, only experts working on the communication of cases and judgments were selected.

The approximately one-hour interviews featured questions derived deductively from the aforementioned research on international organizations, namely organization of the department and personal background, forms of communication, communication strategies and outlook. In order to safeguard the confidentiality of the interviewees, their statements were anonymized in this article. As all the interviewees are currently employed as communication officials, the practices described in this article illustrate a particular period of institutional development, mostly the late 2010s. While this might exclude the historical origins and earlier developments, it puts the current crisis at the centre of the research design.

The professionalization of communication actors

Capacity-building

Over the last decade, all institutional bodies whose officials were interviewed for this piece have developed independent and full-time units, which are in charge of handling the institutional communication. While those teams might organizationally belong to the administrative or secretarial unit, each institution has assigned full-time press officers and communication specialists. Even though the first professional communication efforts at the CoE and the ECtHR have been established in the early 2000s, they have been significantly reformed and expanded in the last decadeFootnote 90 and the most recent one, the Communication Department at the IACtHR, was only established in January 2020.Footnote 91 This form of capacity-building is a crucial step for developing professional institutional communication since it allows institutions to promote long-term strategies beyond the daily routine of court-based activities. For human rights bodies, which are generally underfunded and overworked, it is particularly difficult to establish something as costly as a communication department. Political, organizational and financial resources are required to not only create professional communication, but also maintain it in the long term.

Establishing a separate communication department requires influential leadership able to build broad coalitions of support for this project, both inside and outside the institution. In this respect, the role of individuals who took on the position of executive secretary is crucial. They can act as agents of change for establishing or reforming institutional practices.Footnote 92 For instance, Paulo Abrão, who became the Executive Secretary of the IACHR in 2016, had become convinced of the importance of professional communication for human rights issues in his earlier positions and thus swiftly implemented a new communication strategy. While the Commission had already developed social media accounts on Twitter, YouTube and Flickr, their creation was mainly incidental and the sharing of information was limited to press releases. After Abrão took office, he put together a small team including a communications coordinator and a design expert, and soon hired a social media coordinator. He also created a new communication strategy in 2017 to highlight the voices of victims in all communication instruments of the Commission. This required adding two video documentary professionals to the team in 2018, who started to document all the visits, in situ sessions, missions and other activities of the Commission.Footnote 93

In most cases, the development of communication capacities is a process that can take decades, not years. The experiences of Pablo Saavedra, Executive Secretary at the IACtHR are exemplary in this regard. In his words:

When I assumed the position of Secretary of the Court in 2004, I found a very small court, not well known in Latin America, and mainly for cases involving gross violations of human rights. The court did not have much communication, only the annual report which encompassed more than 1,000 pages with all the resolutions. It was huge. There was not much interaction with the civil society, with the people, nor with the states. This was also true for the academia. Even though some of the judges such as Cancado Trindade and Fix Zamudio were well known academics, there was not much interaction.Footnote 94

In this rather bleak situation, Saavedra prioritized the external communication of the Court. He developed the idea of the IACtHR as una corte de toga y mochila – a Court with robes and backpack:

The [backpack] is a symbol of going to the countries, of visiting the countries, going to the people, to have more interaction. The object of this was to have more legitimacy because it is very easy to have legitimacy when you always talk with the same people. Our main problem was that no one knew about the court. Even today, the people who live in the Americas don’t know about the Court. For this reason, we decided to start having public sessions and hearings in the countries. This was very important. I believe we were the first tribunal to start having sessions in the countries, which included open public hearings, interactions with the universities and civil society in the states we visited. This changed a lot, especially for the visibility of the court.

Over the following years, Saavedra pursued the strategy of an interactive Court that reached out to the people, also regarding the activities of the Court in San José, Costa Rica. In 2007, public implementation hearings started taking place (there were only written submissions before), and since 2010 the public hearings have also been streamed on the Court’s website and social media channels:

This was a massive change. Before, we only had the public hearings here in the courtroom in Costa Rica where at maximum only around 100 people can attend. Now it is open to all of the people in all of the countries and this changed a lot. It had a huge impact. As always in a court, there are always some more traditional and conservative voices. For instance, when we started to visit the countries, some judges thought that this would look like tourism, that they would be criticized for that. They favoured a more traditional court, not a tourist court. And later there was the discussion on the media court. They feared that the court was too fancy, that it would look like a comedy. I said, no one does it, we should start doing that. The traveling court, and the media court changed a lot for the proximity of the judges with the reality and also with the media and the new kind of communication. And after that, we saw that we need to increase our department of communication, but we lacked funds. I tried to work together with another lawyer from the court to become original, to do more communication, but we lacked the time to do different things such as infographics or start using Facebook. It was not enough. We needed some specialists in those matters.

In order to establish new structures for communication, additional funds had to be procured. This is particularly challenging for regional human rights institutions as they have experienced severe budget crises in the context of increasing state criticism over recent years.Footnote 95 The IACtHR relies heavily on external international contributions, in particular from European partners, to fulfil certain tasks such as translations.Footnote 96 Consequently, the Secretariat applied for an EU grant to fund the position of an official spokesperson of the Court in 2014. It received the funding in 2019 and was able to hire the first spokesperson of the Court, Matías Ponce, in January 2020. Ponce, who holds a PhD in public diplomacy, soon implemented an innovative agenda to update and expand the Court’s communication. Even though the new department headed by Ponce only consists of three people who were previously employed in the library of the Court, in the first six months of his tenure he set up a new homepage and infographics, and established a new communication strategy following distinct principles.Footnote 97 This points out the influence even a single communication professional can have in shaping the narrative of the institution.

There is also the possibility that state authorities themselves may want to improve the communication with the institution, and thus invest additional resources. Following Angela Merkel’s visit to the ECtHR in 2008, the German state decided to second a German press officer to the communications team. During the past ten years, this additional person was able to focus on the cases that were interesting for the German press, create German-language media releases, and respond to German media inquiries. This was a unique opportunity for the Court to reach out to the German public and very much welcomed by the press department.Footnote 98 Naturally, this singular focus on one country and one language cannot easily be replicated by the official communication actors, which have to spread their attention over the 47 state member states of the CoE with a large number of languages.

Professionalization

This shift in communication approach, from passive transparency to active outreach, is reflected in the establishment of press units and communication departments. However, to produce professional communication, they also need to be staffed by specialists and implemented in a coordinative manner to produce professional communication.Footnote 99 Even a small number of people can make a huge difference. For instance, at the ECtHR – with eleven staff members the largest communication team in this sampleFootnote 100 – it was possible to significantly diversify activities. In general, the team consists of two separate units: a seven-person press department, which handles the day-to-day activities of the Court, in particular through press releases and the presentation of cases to journalists; and a four-person communication unit, which develops long-term strategies and produces multimedia instruments such as short video clips to inform, explain and legitimize the Court’s activities.Footnote 101 In contrast to its Inter-American counterpart, the ECtHR’s communication strategy remains more traditional, with several interviewees highlighting the ECtHR’s strong focus on being perceived as a neutral and independent legal body.Footnote 102

Nevertheless, the European human rights regime has developed a strong inter-institutional network of communication, which complements the work of its press and media relations with more proactive communication strategies. At the CoE, specific liaison officers link the central 80-person strong communication department of the Council with the smaller press and communication unit at the Court. For instance, the press officers of the Council work on country-specific media relations, and are thus able to monitor the national and foreign-language press. This allows them to address journalists and media outlets specifically and make them aware of upcoming judgments concerning their member state. Proactive engagement with national media outlets by the Council thus complements the very traditional approach of the Court. In contrast, reporting on the activities of the Court as the most prominent institutional organ also reinforces the visibility of the CoE.Footnote 103 Similarly, since the implementation of cases falls into the competence of the CM, the Department of Execution itself began pursuing an independent communication strategy in 2018 by establishing a separate communication team in its information division.Footnote 104 Again, a deliberate choice was made to intensify media and communication when reporting on the implementation of ECtHR judgments.

It must be stressed that the people working in the communication departments are not legal professionals, even though some might have been trained as lawyers. In fact, they mostly consider themselves generalists or communication specialists, either by training or through years of professional experience – for instance, in journalism. The majority of communication officers are early and mid-career professionals, who have gained practical communication experience in international institutions, domestic human rights bodies or the communication departments of different institutional organs.

This recruiting practice contributes to the socialization of a particular class of institutional bureaucrats, who have developed a significant amount of expert knowledge.Footnote 105 This shift towards communication specialists is in line with a broader move towards the professionalization of human rights work. Scholars have analysed how those new types of human rights professionals are characterized by a shared professional identity, including shared values, a body of scientific knowledge and systems to apply that knowledge.Footnote 106 From a sociological perspective, communication professionals in regional human rights bodies stand at the intersection between two different juridical fieldsFootnote 107 – the legal, human rights community that shapes the practice of human rights and the bureaucratic, administrative community that safeguards the organizational functioning. They exercise existential functions for both communities, but are also at the crossroads of professional cultures and ethics. Critics might argue that their focus on attracting media attention, developing an institutional ‘brand’ and creating positive narratives further entrenches the ‘marketization’ of human rights and global justice in the media age.Footnote 108

Communication professionals demonstrate significant inter-professional mobility and specialized knowledge. In the context of organizational ecology, they are not loudspeakers, but converters. Their main focus is not to increase the volume of the Court’s decisions, but to ‘shape those documents in an accessible, clear manner’.Footnote 109 Throughout the interviews, officials have stressed that their immediate objective lies in the translation of technical expertise for a general audience.Footnote 110 In this sense, they act as transmission belts between the institution and the public, and ensure the accessibility of the institution on a vertical dimension. However, on a systematic level, they also pursue more systematic improvements such as transforming the general institutional approach of the institution towards the outside world in order to be responsive towards the current political climate and generate loyalty. This is what an official of the IACtHR described as establishing a culture of communication inside the institution:

My most important objective is to develop a culture of communication inside the Court, with the judges, lawyers, secretaries and so on, in order for them to better understand the value of communication for the legitimation of the whole institution … It is most important that all members of the court are understanding the communication and how it can improve the legitimacy of the court. That they understand the importance of translating the decisions of the court to the different audiences and different targets and of course this is new for most of them.Footnote 111

The influence of communication officials thus exceeds any official job description and may trigger meta-institutional change. Moreover, this systematic approach highlights how institutional decision-makers have discovered professional communication as an instrument of strategical legitimation. Throughout the interviews, communication professionals of both regimes emphasized that they were very much aware of their role in the current crises of human rights courts. They highlighted their responsibility to not only counter these crises but also to develop long-term strategies to combat increasing state attacks:

We want the judges and lawyers to understand the work of the communication, and all the aspects of communication, such as the role of the spokesperson of the Court, our communication team, and of communication in general. This is especially important in our current political climate, with increasing state attacks on the Court. Hence, a Court without a good communication team and strategy falls prey easier to those attacks.Footnote 112

There is significant evidence that the professionalization of institutional communication is a response to the backlash experienced by regional human rights courts. For instance, at the CoE, the stalemate with the Russian Federation over voting rights and Russia’s refusal to pay its financial contributions has fuelled the need for improved communication as an instrument to create long-lasting institutional loyalty:

You have to invest resources and time to improve communication, which was not the case some time ago and it is more and more of a case today. [The Russian situation] also awakened the fact that … if you are relevant to them, people pay more attention and be more defensive: hey, you cannot target this institution. That is what the Council of Europe as a whole realized. We have to be known and respected for what we do – we cannot be pushed or considered non-important. We need savoir fair – faire savoir; we need to know how to do something, but we also have to do the things which make us known. Both are equally important. At the Council of Europe, we have skills and knowledge but we have to make others aware that we know this and that we have those skills. And this is key to avoid being considered not important, being pushed around, or not treated with the resources we need.Footnote 113

So what do those communication strategies for combatting backlash look like? While interviewees have confirmed the existence of guidelines and strategy papers, those are considered internal working documents and are not publicly accessible. However, from the interviews, it was possible to deduce significant information on working methods that emphasize systematic reforms to communication practices, both regarding the audiences that communication agents want to reach and the instruments they deploy. In the following section, I will analyse how those developments correspond to the two strategies for the creation of loyalty identified earlier.

The evolution of communication strategies in times of backlash

Expanding audiences

The first step for the creation of loyalty is to raise social awareness about the existence of an institution. This is particularly challenging for international courts as their judgments address only the parties to the dispute: a state party and alleged victims. In particular, when communicating judgments or reporting on their implementation, courts and quasi-judicial bodies focus exclusively on the authorities of the respondent state. Those communication practices can generally take three forms: praise, criticism and non-communication. For instance, in the implementation stage, the communication could focus on positive steps implemented by the state parties such as an updated action report. It could also criticize states – for instance, by pointing out in a press release or a meeting with state authorities that a particular judgment still lacks implementation, or that the steps taken were insufficient. Most paradoxically, effective communication to state authorities could also mean remaining silent. In the words of one communication official:

Sometimes it is easier to make progress when there is not a huge amount of visibility on a case. You have to strike a balance sometimes between trying to maximize visibility when you think that can help move things along, and you have to know when not to say anything at all. This can be seen a bit lacking in transparency, but if it helps to move things forward and raise human rights standards and get people released from prison, then I also see that as being effective communication – knowing when to be quiet. Effective communication is what we can do as communicators to help get judgments implemented, which does not always mean generating headlines.Footnote 114

The goal of effective communication becomes particularly challenging in hard cases – for example, states that have a difficult relationship with the institution, or a bad record of implementation. In general, interviewees have emphasized that their communication is no different when addressing generally compliant versus critical state parties. However, in a situation in which the state party is openly critical of the institution, reaching the general public and providing a counter-narrative become priorities.

Language is a huge obstacle to effective communication. Several interviewees have highlighted this as a problem of their communication strategy and something that they would hope to improve in the future. The European human rights bodies generally communicate in the two official languages of the Council: English and French. As the press and communication departments are institutionally separate from the language services and lack the resources for official translations, communication in other languages depends on the personal capacities and effort of communication professionals and thus can only be done on a case-by-case basis. For instance, at the Department of Execution, Bulgarian and Hungarian lawyers were able to prepare press releases for important cases in their native countries, which significantly increased the amount of attention these cases received in the national news.Footnote 115 These are not isolated events: the statistical analysis of the Department demonstrates that information in the national news spreads faster and wider when the original press release is in the local language rather than in English or French. Moreover, the homepage of the Department of Execution, along with all the important documents and guidelines, features a Russian version.Footnote 116 This is interesting, as the two other main languages of the Council, German and Italian, are not included and might suggest a particular attention to Russia, one of the most ardent critics of the European human rights system. Similar problems also exist in the Inter-American system, where the lack of resources means that most instruments are only available to Spanish-speaking audiences. The absence of English and Portuguese material complicates reaching the Caribbean states, not to mention Brazil. This is acutely felt by the communication officials, but with limited financial means creative solutions have to suffice. The IACtHR, for instance, is already cooperating with several Brazilian universities and hopes to adopt a special internship program to develop a Portuguese Twitter account.Footnote 117 The availability of communication material in the respective languages is thus of utmost importance to reach audiences, in particular in those states in which populist governments rally against human rights bodies.

While the European human rights regime is still rather state-focused, the Inter-American system has embraced a more victim-centred approach. In the Inter-American human rights bodies, victims are at the front and centre of many activities, their names are eponymous to prominent judgments and they are also involved in the implementation hearings. This is very different from the European bodies, which generally refer to the ‘applicant’ as one of the two disputing parties. The 2017 communication strategy of the IACHR is built around the idea of victim-centred communication – a marked shift in its prior practice.Footnote 118 Since then, the Commission, just like the San José Court, aims to highlight the experiences of victims in its communication. This allows the Commission to demonstrate the importance of its activities by showcasing an individual’s experience while at the same time allowing third persons to empathize and identify with the victim. For instance, the 2018 Nicaragua mission, which for the first time put the stories of individual victims at the centre of its social media activities, resulted in victims and civil society increasingly addressing the Commission proactively, again highlighting that loyalty requires interaction between the institution and its constituents:

In the mission in Nicaragua, we had a press professional there and we tweeted a lot about it, and we saw that it had an immediate effect on people’s lives. So when people were illegally detained, human rights organizations came to press the Commission to make a statement regarding this person’s specific situation. Especially after Nicaragua, we saw the power of the Twitter statement which had an immediate effect. For instance, a tweet of the Commission was on the front page of all the major newspapers in Nicaragua every day. One single tweet was able to influence the agenda of the whole country. This positive experience also led other Commissioners to request tweets on the situations they were monitoring, the thematic issues or countries they were rapporteur for. At some point during the last and this year, we realized that we almost switched our main strategy to communication. We still send out a lot of press releases to traditional media, but it decreased a lot. Since 2018, you can see that the Commission is quite proactive in immediately responding and attending the main situations in the hemisphere … We also have the positive effect that victims and civil society organizations write to the Commission, requesting the Commission to make a statement because they see that the Commission responds. They see that the Commission raises awareness, they provide more information and request the Commission to respond through social media. This is also increasing. It shows how they trust the Inter-American system and how they see another channel to have direct access and dialogue to the Commission and have an immediate response to some specific situation that they want attention for. This is also something new.Footnote 119

Similar experiences have also been shared by communication officials from the IACtHR. With only a few cases per year, the Court strategically highlights the story of individual victims to showcase patterns of human rights violations across the region. The idea is to empower individuals in a similar situation to act – after all, even though the specific victim might be from Chile, the same type of cases can be found in Brazil, Argentina or Mexico.Footnote 120 Hence, the victim-centred approach transforms the idea of the public as a neutral arbiter to the public as a collective of people that is (potentially) directly affected by the human rights regime. In many instances, the human rights violations addressed by the Court are structural and the types of reparations required by the Court reflect that. Highlighting the positive impact of the activities of human rights bodies upon individual victims can thus not just demonstrate the effectiveness of the Court, but also showcase its relevance for various communities across the region.

So how does this relate to the creation of loyalty? First, all interviewees highlighted that their attempts to expand to new audiences have been successful even though challenges remain – for instance, in reaching specific audiences with a different language such as those in Brazil. This increase in attention and knowledge among the general public can then be used to portray positive narratives in favour of the institution. For instance, a recent survey experiment by Elias Dinas and Ezequiel Gonzalez Ocantos in the United Kingdom, one of the most critical constituents of the ECtHR, has highlighted that providing the public with positive arguments on the Court helps to contain backlash.Footnote 121 Moreover, the statistics of institutional engagement can account for increased interaction with the general public. For instance, at the IACtHR, both the Spanish-speaking Facebook and Twitter accounts grew significantly in the last year to 537,485 followers (23,831 more than in 2018) and 350,058 followers (82,717 more than in 2018), respectively.Footnote 122 Even the Instagram account, which was opened on 1 May 2019, reached more than 27,000 followers in its first 18 months.Footnote 123 The ECtHR also reports a significant positive development of public communication, with a 14 per cent increase of online visits to the case law database HUDOC in 2019 to more than 4.5 million visits a year, as well as 8.3 per cent increase in general website visits (including HUDOC) to more than 7 million visits in 2019.Footnote 124 Moreover, its Twitter followers grew from 13,000 in 2016 to 30,000 in 2020.Footnote 125 This shows it is not only a positive belief in the court (sociological legitimacy) that is generated through professional communication, but also active interest among the general public to have increased interaction with the institution – in other words, loyalty.

Activating communities of practice

The second pillar for the creation of loyalty is the activation of communities of practices, which have the potential to safeguard the authority of the institutions against both internal and external threats. Both the European and the Inter-American regime are embedded in human rights communities of legal actors, some of which date back more than five decades.Footnote 126 This means that, in the current crisis, communication practices do not need to aim at establishing those communities, but rather at activating them. In order to tap into their potential, communication practices must thus not only relay general information to the public, but also allow the institution to engage in a dialogue with specific communities.Footnote 127 This sounds relatively simple, but it poses a major organizational hurdle for communication departments. While a selection of specific communication addressees has to be made, it is difficult to pre-assess which communities might be more receptive to foster loyalty among them vis-à-vis human rights courts.

Communities of practice are neither homogenous nor without internal strife. As they develop organically through the lifetime of an organization, the respective actors vary significantly in their socialization, size and legal culture, ranging from journalists and grassroots activists to religious communities and bar associations. A community of practice is not clearly defined from the outside, thus its structure is rather flexible. The interests and needs of its members are also not always aligned. This diversity requires institutions to develop specific types of communication practices to reach distinct audiences, which are not necessarily complementary. With limited resources and a high number of human rights violations, communication professionals have to decide on the selection of audiences, instruments and ultimately topics to be covered. In principle, this can even result in conflicting narratives or messages. Moreover, some actors are more suited to engage in a dialogue than others. On the one hand, communicating primarily to intermediaries such as journalists or media actors might help to disseminate information broadly to the general public, but the relationship to journalists is usually rather one-sided. On the other hand, communicating to actors who are directly involved, such as state agents, human rights experts and alleged victims, requires significant impartiality and is thus bound to disappoint at least one side.

This is why communication officials have identified selected communities that they aim to address specifically. From the interviews, it was possible to identify several core stakeholders in the communities of practice surrounding each respective court which the institution attempts to address through their communication. While these are only isolated insights and should not be understood as excluding further audiences, it helps to understand to whom the institutions primarily aim to speak and, consequently, how the specific information has to be shaped by the communication professionals.

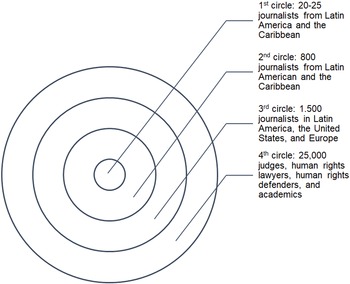

In the European human rights regime, one official differentiated between three ‘circles’ of targets (see Figure 1). The first circle is considered the main target and primary addresses of the communication. It consists of experts, state delegations and human rights lawyers – that is, parties to the dispute – who closely follow specific ECtHR judgments and their execution. Important but subordinate audiences are human rights institutions, NGOs and academics who have a connection to the institution but might not be directly involved in cases (second circle), or the general public (third circle).Footnote 128 The primary aim of the communication strategy of the European institution is thus to reach the first circle and strengthen the relationship with those communities of practice – for instance, via missions, conferences, roundtables and workshops. Those communication activities, which are then also published in official reports and social media channels, provide direct contact and are considered to be more effective.

Figure 1 Circles of communication in the European human rights system

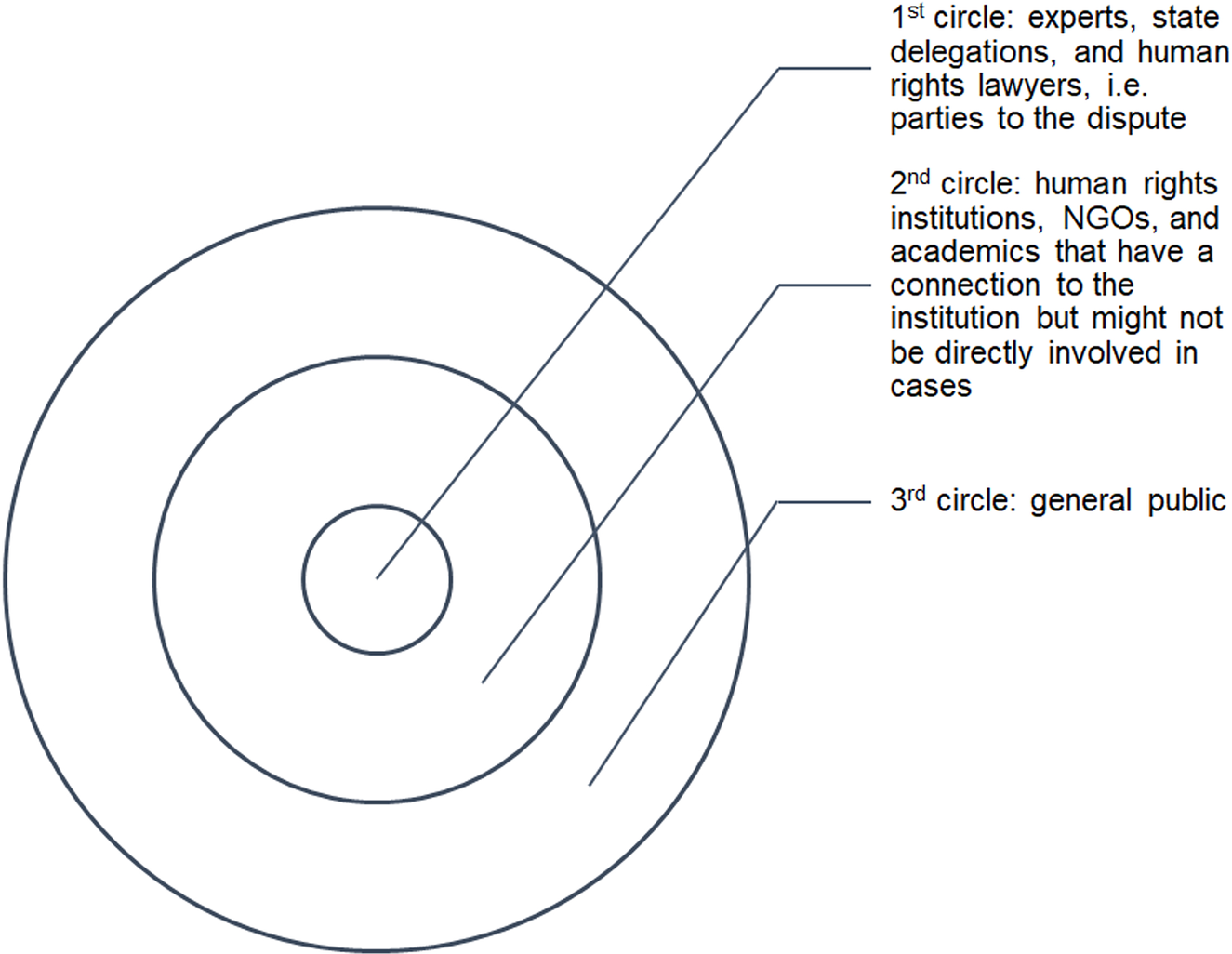

Both the IACHR and the IACtHR have long organized missions and sessions abroad.Footnote 129 The IACHR’s mandate includes the monitoring of situations of human rights violations, and thus requires timely responses to ongoing crises. As discussed earlier, this facilitates a fast-paced approach to communication – for instance, video reporting and live-streaming, as well as social media during in-person visits of the Commissioners. On the other hand, the new communication strategy of the IACtHR is focused primarily on reaching specific audiences even when the judges are not visiting the region. Consequently, the first targeted group is journalists, who can act as mediators to the wider public. The IACtHR has organized them into a network with overlapping circles (Figure 2). The first circle consists of around 20–25 journalists from Latin America and the Caribbean, who are handpicked by the Court. They have access to a weekly meeting with Court officials and thus dispose of a wide range of information and close collaboration with the Court. The second circle of journalists consists of approximately 800 journalists, which the Court has grouped according to countries of origin and tries to keep up to date with country-related information on specific cases and investigations. In the third circle, there are around 1,500 journalists in Latin America, the United States and Europe, with whom the Court shares general information about the work of the Court to improve the understanding of the Inter-American human rights system. Next to this network of journalists, the Court has developed a database of over 25,000 contacts all over the world, which constitute the second important group of stakeholders the Court aims to address: judges, human rights lawyers, human rights defenders and academics. This database allows the court to develop more targeted messages, whether via the traditional newsletter or specialized groups on LinkedIn.Footnote 130

Figure 2 Circles of communication in the Inter-American human rights system

Comparisons between the regional systems can be made. Broadly, the European human rights regime focuses its communication primarily on important stakeholders that are already involved in its activities such as state delegates and human rights professionals, while the Inter-American system focuses on intermediaries such as journalists. However, this also reflects the internal institutional structure of communication in the respective regional system. For instance, in the European system, the connection to journalists and media actors is also handled via liaison press officers at the Council of Europe. Similarly, the IACHR and IACtHR differ not only in the temporality of their activities but also in their workload. While the IACHR has to monitor a multitude of current situations of human rights violations and process thousands of complaints, the IACtHR only hands out around 15–30 judgments per year, very often long after the violation has taken place. Hence, its focus is on disseminating the information rather than attracting the attention of the regional public to an ongoing crisis. This determines the type of loyalty ties that can be made, balancing between fostering long-standing relationships with specific regional NGOs, such as the Center for Justice and International LawFootnote 131 or international foundations such as the KAS,Footnote 132 and more ad hoc initiatives to increase the visibility of human rights in a situation of crisis.

In addition to developing proactive communication strategies, human rights regimes have also attempted to increase the general accessibility of information to the aforementioned communities. This holds true not only for the various modern communication formats on social media, but also for more traditional communication instruments. For instance, in the last years, the IACtHR and the Department of Execution have both revamped and streamlined their homepages to make information more readily accessible. At the execution department, this led to a 30 per cent increase in website traffic in 2019.Footnote 133 Moreover, several additional communication outputs are provided to interested parties, such as case summaries, country fact sheets, thematic overviews and Q&A brochures.Footnote 134 The ECtHR was the first institution to provide those thematic fact sheets after a change in secretarial management ten years ago, and now offers more than 60 fact sheets that are updated regularly.Footnote 135 By re-narrating judgments in an accessible manner, interested stakeholders and local actors can learn of and rely on the human rights jurisprudence. It also lowers the reliance on state authorities to disseminate and translate the respective jurisprudence to domestic audiences, as well as the inherent risk of being misunderstood or intentionally misinterpreted.

Even the most traditional judicial communication instrument, the press release, has been reformed over the last decade to make it more accessible. The press release is a particularly challenging instrument, as it must follow a very specific formula and be written in a neutral and impartial style, and generally includes very technical language. For the ECtHR, the press release is still the most important communication instrument. Among the 2,000 people who receive them regularly, three communities are the main addresses of press releases, namely journalists, representatives of governments and academics.Footnote 136 The ‘grey box’ at the top of the press release includes the main info about the case. In contrast, the IACtHR has abandoned the traditional judicial approach and developed a simplified and clearer style of press releases.Footnote 137 Since the establishment of the communication department in 2020, the press releases are now written by communication officials, not the lawyers. They are significantly shorter and integrate many insights from communication studies – for example, instead of long and empty case names, they emphasize the core message in the title (‘For the use of racial profiles Argentina is responsible for the illegal, arbitrary and discriminatory detention and subsequent death of an Afro-descendent person’).Footnote 138 In the press release, the judgments are also more contextualized and technical language is avoided in order to make them more intelligible to communities that lack legal expertise, such as journalists and the general public. This enables human rights bodies to reach out to respective audiences directly and thus foster loyal relationships.

It is difficult to assess whether those communication activities are sufficient to activate communities of practice in times of backlash, yet, a number of recent interactions can be identified. An example might be the public outcry following the joint declaration by the governments of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Paraguay in 2019.Footnote 139 In this declaration, the five signatory states, which represent 70 per cent of the region’s population and 80 per cent of its gross domestic product,Footnote 140 reaffirmed their commitment to the Inter-American human rights system, but also put forward several reform proposals. Those were mostly aimed at strengthening the principle of subsidiarity and broadening the states’ discretion in the implementation of judgments. While this does not amount to a backlash per se,Footnote 141 it triggered an avalanche of civil society voices in defence of the Commission’s activities. More than 200 organizations and persons of the region signed a common statement against the joint declaration, which they interpreted ‘to reflect a coordinated effort to weaken the promotion and protection of human rights in the continent, as it looks to cut back on the powers of the Interamerican Commission and Court of Human Rights’.Footnote 142 Similarly at the ECtHR, the draft of the 2018 Copenhagen Declaration and its strong emphasis on subsidiarity has also been heavily criticized by a network of academics, NGOs, national human rights institutions and members of national parliaments in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). Their outspoken criticism was ultimately shared by a number of state parties, which succeeded in watering down the most criticised aspects and changing the overall tone of the declaration. A third situation in which loyal non-state actors played an essential part occurred in the context of the crisis between Russia and the CoE in November 2018, when a large number of Russian human rights defenders published a memorandum to appeal to ‘all the stakeholders involved in discussions and decision-making within the Council of Europe, including parliamentarians and executive authorities of the member states’ to prevent a Russian withdrawal.Footnote 143

What became clear in the interviews is that communication officials in both the European and Inter-American human rights regimes do not just wish to expand their general audiences; they have also identified specific communities they want to address and developed the respective instruments required to do so. Among the instruments that have been deployed to counter the rising criticism over the last decade, one dominant trend can be observed: the use of new instruments, in particular visualization and story-telling, which will be analysed in the following section.

Visualization and storytelling