A. Introduction

The right to an effective remedy and the right of access to courts are fundamental rights protected at the European level by both the European Convention of Human Rights and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.Footnote 1 The European integration process has led to the creation of various mechanisms of enforcement of EU law, which makes the path towards access to courts complex and uncertain, because they call into question the boundaries between the national and European spheres of jurisdiction. At the beginning of the process of European integration, these boundaries were rather strictly defined. This is because—as a matter of principle—the enforcement of EU law was mainly organized according to the system of indirect administration, which implied that the national administrative authorities were first and foremost competent to enforce EU law.Footnote 2 The system of indirect administration has been noticeably limited by the development of the system of “co-administration,” or, “composite administration.” This development brought about the much debated need to define the articulation of the respective jurisdictions of the national and European courts on the administrative acts resulting from those procedures.Footnote 3

Another product of European integration which has been analyzed less by scholars, and is less visible in the European Court of Justice (ECJ)’s case law, is that of transnational administrative acts. These are administrative acts which, by reason of the authority that adopted them, the scope of their effects, their addressee(s), and/or their decision-making process, are “in-between” at least two national legal orders. They are thus a sub-category of the acts adopted following co-administration proceedings, because the latter concept entails both vertical and horizontal mechanisms of administrative cooperation.Footnote 4 Alternatively, the scope of transnational administrative acts is limited to horizontal relationships—i.e. those involving exclusively national administrative authorities.

The issue of judicial review of transnational administrative acts or decisions is not peculiar to European Union law. This type of decision also exists outside the EU legal system, insofar as national administrative authorities from at least two different States are involved in the adoption of an administrative act.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, it is equally true that the European Union is a privileged playground for the development of administrative acts of this type, especially because of the existence of various and diverse administrative cooperation mechanismsFootnote 6—including regulatory structures of purely horizontal cooperation.Footnote 7

The question of the availability of judicial review in the context of transnational administrative acts is a complex one, for at least two reasons.Footnote 8 First, the transnational dimension of an administrative act brings about “contact” between two national legal orders which are at the same level, and between which there is—in the majority of cases—no relationship of primacy which has been designed to solve the conflicts of laws or the conflict of jurisdictions.Footnote 9 Additionally, according to the basic principle of territoriality of administrative law,Footnote 10 national administrative courts are only competent to review the legality of acts and actions adopted by the authorities of their legal order. However, in cases of transnational administrative acts, the presence of one exogeneous element may disrupt the straightforward path toward the right of access to the courts, as both the determination of the competent court and the scope of the review carried out by the court seized become uncertain. Transnational administrative acts may thus question the orthodox limitations for administrative courts to review a foreign administrative act.

This Article argues that the transnational dimension of an administrative act affects the classical approach towards its review, because the fundamental principles of administrative law may have trouble accommodating this peculiar regulatory mechanism. Nonetheless, in the context of European integration, these fundamental principles governing jurisdiction must be reconciled with the requirements arising from European Union law. Specifically, European principles—such as the right to effective judicial protection or the principle of non-discrimination—require an adaptation or an even greater flexibility of the classical boundaries of judicial review of administrative action.

This Article, after analyzing the complexity of the concept of transnational administrative acts, considering its links with those of extraterritoriality and transnationality (Section B) and drawing up a typology of transnational administrative acts (Section C), will consider the applicable principles for determining the competent court (Section D). Based on the established typology of transnational administrative acts, this Article will eventually analyze the possibilities of judicial control over transnational administrative acts (Section E).

B. From Extraterritoriality to Transnationality

Public administration is no longer a State function that is exercised solely within the national legal order to which it belongs. It acts in connection with the international legal order and also with foreign legal orders. Transnational administrative law aims to address the latter aspect. Understood in this connotation, transnationality has the same meaning as internationality as understood in private international law—given the presence of a foreign element in a legal relationship—and therefore differs from internationality as understood in public international law.Footnote 11

If we focus on administrative transnationality as manifested in unilateral administrative acts, the concept of extraterritoriality ought to be added to the analysis. Unlike a contract, a unilateral administrative act is the product of only one legal person and is therefore necessarily, as a matter of principle, linked to the legal system to which its author belongs. Nevertheless, its enforcement may not be located solely in this legal system. This phenomenon can be linked to that of extraterritoriality, which has been the subject of numerous meticulous investigations by public international law scholars.Footnote 12

Brigitte Stern considers that “there is extraterritoriality in the application of a norm if all or part of its process of application takes place outside the territory of the State that issued it.”Footnote 13 She further specifies that the application of a norm is an operation with different dimensions: “[T]hus, elements of extraterritoriality are found when a norm is implemented by an authority outside the territory, or when elements outside the territory are taken into account in the implementation of a norm, or when the application of the norm involves legal effects outside the territory.”Footnote 14 In those cases, the jurisdiction of a State extends beyond its territory.Footnote 15 This notion of extraterritoriality may be applied to unilateral administrative acts—as one category of norms in a broad sense—and also to all unilateral legal measures enacted by the State organs of a given legal system.

Public international law distinguishes extraterritoriality according to whether a unilateral action of the State is at stake, or whether the action takes place within the framework of an international treaty or an international organization, including the European Union.Footnote 16 In the first hypothesis, extraterritoriality often encounters a number of obstacles, both legal—in particular its conformity with the rules of public international law—and practical, the difficulties in giving concrete form to an extraterritorial claim. In the second hypothesis, extraterritoriality takes a cooperative shape—it is governed by the treaty establishing it, or by the law of the international organization in which it is enshrined. In the European Union, where the free movement of both natural and legal persons is ensured, cooperation between the administrative authorities of the Member States is necessary to deal with different transnational situations.

Finally, following Prosper Weil, two sides of extraterritoriality ought to be distinguished.Footnote 17 In the first, the State, author of the norm, intends to apply the norm outside its territory—this is what the author refers to as “normative jurisdiction.”Footnote 18 The norm is conferred by its own legal order a spatial scope of application that goes beyond its territory.Footnote 19 In the second, the State applies a foreign norm within its own territory and thus confers an extraterritorial effect on that foreign norm.Footnote 20 This is a case of so-called “recognitive jurisdiction.”Footnote 21 In the case of administrative co-operation, as the eco-system in which EU-generated transnational administrative acts move, this distinction should be viewed in context, because it is by virtue of this specific legal framework that an act of a State A may produce effects in State B, or require the authorities of State B to apply the acts of State A. Nonetheless, this distinction has the merit of highlighting the fact that both authorities of the State from which the act emanates, and also foreign authorities, are often involved in the framework of transnational administrative acts. It also demonstrates that, frequently, a transnational administrative act is part of a chain of acts adopted by authorities of a distinct legal order. Thus, an administrative act from State A allows the enactment of another administrative act from State B, which in turn allows the enactment of another administrative act in State A or even in State C.

In the next section, this Article will explore how the notion of extraterritoriality, elaborated by Stern, and the typology proposed by Weil, can be used to draw up a typology of transnational administrative acts, which are to be regarded as being “in-between” at least two national legal orders.

C. Typology of Transnational Administrative Acts

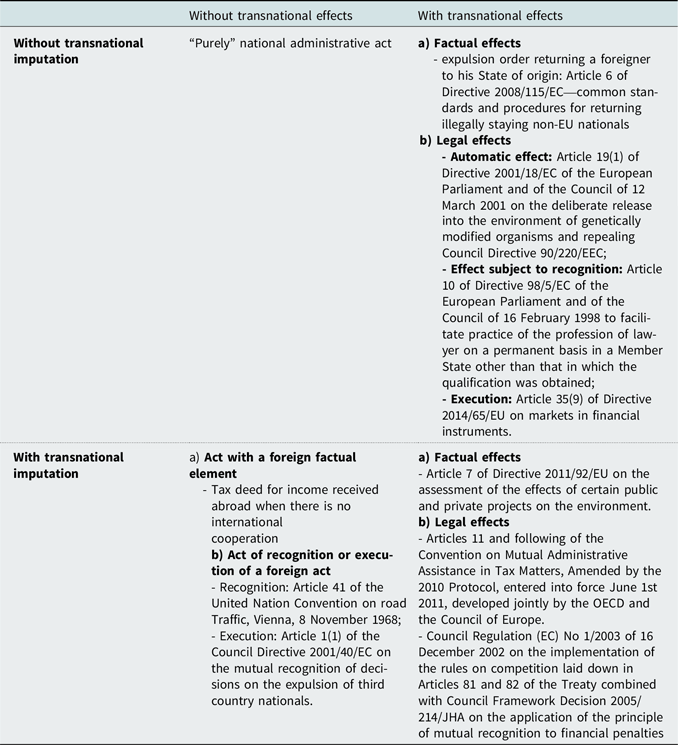

In order to create a typology of transnational administrative acts, it is possible to use a distinction made by Brigitte Stern.Footnote 22 This allows one to distinguish between the notions of transnational imputation and transnational effect.Footnote 23 An administrative act can be considered of transnational imputation when, for its adoption, it takes into account facts or legal situations existing outside the territory of the authority that enacts it. The foreign element is, in such a case, the basis of the act. An administrative act may instead be considered to have transnational effects if it has consequences outside the territory in which it was enacted. The foreign element is thus the consequence of the enforcement of the act. These two hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as administrative acts may be both of transnational imputation and with transnational effects.

I. Acts of Transnational Imputation

The act of transnational imputation may itself take different forms. It may be an act that necessitates, for its application, from a factual element located abroad. The simplest and best-known example is the worldwide taxation principle. The income of a person residing in a State is taxed in that State regardless of whether the income is produced there or abroad. The act of taxation is therefore enacted on the ground of national as well as foreign facts.Footnote 24

The existence of such a factual element located abroad may imply, within the framework of a process of administrative cooperation, that a transnational procedure presides over the enactment of the administrative act of transnational imputation. This is indeed the case, for example, in tax matters, where States exchange information in order to determine a taxpayer’s overall taxable income.Footnote 25

Another example is that of Directive 2011/92/EU on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment.Footnote 26 This instrument provides that, where a project has an impact on the territory of another Member State other than the Member State where the project is to be authorized, “a public inquiry” may also take place in that State. The authorization given to such a project will thus be issued on the basis of factual elements located in the territory of another State.

An act of transnational imputation may also be an act of recognition. In such situations, a State will issue an administrative act in order to give effect to another administrative act issued in another State. By giving effect to a foreign act in its legal order, the act of recognition constitutes an act of transnational imputation, because its raison d’être lies in an element located in a foreign legal order. The best-known example is that of driving licenses. An international treaty adopted within the framework of the United Nations organizes this mutual recognition of driving licenses.Footnote 27 States may also decide unilaterally to recognize a foreign driving license. In France, this possibility exists for nationals of countries outside the European Union who become residents in France.Footnote 28

In a relatively analogous manner, an act of transnational imputation can also be an act of execution. In this case, the State will not merely recognize the legal effects of the foreign act, but will also give it concrete execution. For example, Article 1(1) of Council Directive 2001/40/EC allows a Member State to enforce an expulsion decision taken by an authority of another Member State against a third country national.Footnote 29 The execution measure is an act of transnational imputation, because it gives effect to a measure adopted by a foreign legal order. It should be stressed that transnational acts of execution are often by-products of underlying mechanisms of administrative cooperation. In such situations, the transnational administrative act of State A is conditioned by an administrative act of State B, which will pose a certain number of difficulties at the stage of judicial review.Footnote 30

II. Acts with Transnational Effects

To begin, it is necessary to mention that, outside any cooperative process, a State may intend to give extraterritorial effect to an administrative act it enacts. The best-known example is that of the Amato Kennedy’s laws, which allowed the President of the United States to impose sanctions on foreign companies that invested in Libya or Iran.Footnote 31

In the vast majority of cases, however, the transnational effect of an administrative act is set up by an international treaty or by European Union law. In those cases, States may provide that some of their administrative acts will produce effects beyond the limits of their territory. These can be factual or legal effects. An act produces de facto transnational effects when it has an impact or is likely to have an impact on the territory of another State. One example is an environmental authorization in a border area or an expulsion order returning a foreigner to his State of origin.

Instead, an act produces a legal effect mainly when it has an impact on the legal situation of a person, property, or a good located in the territory of a State other than the State of the authority that enacted it. This effect can manifest itself in different ways.

First, this effect may be automatic and not require the intervention of the receiving State. For instance, Article 19(1) of Directive 2001/18/EC provides that:

[W]ithout prejudice to requirements under other Community legislation, only if a written consent has been given for the placing on the market of a GMO as or in a product may that product be used without further notification throughout the Community in so far as the specific conditions of use and the environments and/or geographical areas stipulated in these conditions are strictly adhered to.Footnote 32

The transnational effect of a decision placing a GMO on the market is therefore automatic.Footnote 33

In a second scenario, the act will produce an effect beyond the territory of the State of the authority which enacted it, only if it is followed by an act of recognition by the receiving State. For example, in order to ensure freedom of establishment for lawyers, Article 10 of Directive 98/5/EC requires a decision by the competent authority of that State to permit assimilation to the profession of lawyer in the host Member State.Footnote 34 The transnational effect in this scenario is therefore subject to an act of recognition.Footnote 35

In a third scenario, the concerned act is an act which does not only produce legal effects, but also requires concretization. Therefore, it may imply an act of execution. EU law sometimes provides for the possibility for the State which is the author of the act to enforce it extraterritorially. According to Article 35(9) of Directive 2014/65/EU

[E]ach Member State shall provide that, where an investment firm authorised in another Member State has established a branch within its territory, the competent authority of the home Member State of the investment firm, in the exercise of its responsibilities and after informing the competent authority of the host Member State, may carry out on-site inspections in that branch.Footnote 36

Therefore, in this case, there is a system of transnational execution. The act has transnational effects because foreign administrative authorities are obliged to execute it in their legal order. This solution is all the more remarkable in that it derogates from the principle of prohibition of extraterritorial enforcement laid down by the Permanent Court of International Justice in the Lotus case.Footnote 37

III. The Links Between Transnational Imputation and Transnational Effects

As discussed above, if an act is of transnational imputation, it is that way only because it concerns a situation that is not solely located in the territory of the State charged with enacting the act. There is instead a factual or legal element of the act that is extraterritorial. An act of transnational imputation can also produce transnational effects, or be part of a chain of acts, in which acts of transnational imputation and acts of transnational effect are interlinked. These links between transnational imputation and transnational effects are found in situations of administrative cooperation where extraterritoriality is not unilateral, but organized through an international treaty or European Union law. Indeed, administrative cooperation is a means for States to ensure the effectiveness of their public policies in cases where they intend to regulate transnational situations.

In a first scenario, the same act can be both of transnational imputation and have transnational effects. When a national act is likely to produce a factual effect abroad, the administrative cooperation that is established appears as a response to that factual effect. For example, the aforementioned Directive 2011/92/EU—on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment—also allows the organization of a public inquiry in the territory of a border State, where a decision is likely to have a de facto effect on the territory of this State.Footnote 38 Here the transnational imputation of the act—for example, the fact that the final act of the decision-making process, an authorization, must take the results of the consultation organized in a foreign State into account—is the consequence of the de facto transnational effect of the decision.

There are also acts that produce transnational legal effects, while at the same time being of transnational imputation. Administrative cooperation in tax matters provides an example of such a situation. When the authorities of State A request information from the authorities of State B, the request for information is an act of transnational imputation, because it is based on facts located in State B—in other words, the fact that is at the origin of the request for information—but it is also an act with transnational effects, as the authorities of State B will have to respond to the requests of State A.Footnote 39 Insofar as administrative cooperation does not only concern the exchange of tax information, but also the recovery of tax claims, the act of taxation can be regarded as an act of transnational imputation. This is not only because it concerns foreign income, but also because it produces transnational effects, as it will have to be executed by foreign authorities.Footnote 40

This link between transnational imputation and transnational effect exists in many acts adopted by the national authorities of the Member States of the European Union in the implementation of EU law. For example, under Regulation 1/2003, national authorities may be given the power to impose administrative sanctions against foreign companies.Footnote 41 Such sanctions constitute an act of transnational imputation insofar as it concerns the conduct of a person located within the territory of another Member State. To the extent that these sanctions fall within the scope of Council Framework Decision 2005/214/JHA on the application of the principle of mutual recognition to financial penalties,Footnote 42 they also produce a transnational effect.

In a second scenario, there is a chain of administrative acts in which an act of transnational effect and an act of transnational imputation follow one another. This is the case in mutual recognition mechanisms. Where the act with transnational effects of State A does not produce an automatic effect abroad, it requires an act of recognition in State B, which therefore constitutes an act of transnational imputation.Footnote 43

It is possible to summarize the typologies of transnational administrative acts as shown in the table below.

D. The Relevant Principles to Determine the Competent Court to Review a Transnational Administrative Act

The determination of the competent court to review a transnational administrative act may not be straightforward. Due to the act’s transnational dimension, as well as its administrative nature, it is worth recalling that the question of the competent court cannot be solved according to the classical principles of private international law.Footnote 44 Indeed, the resolution of this problem presents certain specificities, given the link between the exercise of public power—and thus of State sovereignty—and the adoption of an administrative act. It is worth noting in this respect that the Brussels I Regulation, which provides for conflict rules applicable for the determination of the competent court is not applicable to “administrative matters or to the liability of the State for acts and omissions in the exercise of State authority (acta iure imperii).”Footnote 45 The rationale for this exclusion is rooted in the idea that the assessment of the legality of an administrative act is an exercise which is closely linked to the exercise of State sovereignty. Classically, judicial review is a mechanism which aims at safeguarding the respect of the rule of law,Footnote 46 and thereby the validity of rules in a given legal order. It is up to the national court of the particular national legal order to ensure that valid norms are enforceable in that State’s order. The relevant principles applicable to determine the competent court to review a transnational administrative act are thus those resulting from classical public law rules, as supplemented—in the context of the EU—from European Union law.

First, the question of the court having jurisdiction to review an administrative act is solved by referring to the principle of territoriality of administrative law, according to which the administrative situations of State A are intended to be governed solely by the law of that State. This principle, which itself derives from the notion of national sovereignty, makes it impossible to subject the exercise of public authority to a foreign State. The same logic underlies jurisdictional immunities under public international law.Footnote 47 For this reason, a court has no power to review the legality and thereby potentially affect the validity of an act produced by a foreign State. Consequently, as a matter of principle, an action against a foreign administrative act—such as an act adopted by a foreign public authority—is not admissible before a court belonging to another legal order.

Second, in the context of European law, any solutions developed in order to review transnational administrative acts, adopted to enforce EU law, must comply with the principle of effective judicial protection and the right to an effective remedy enshrined in Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, as well as the European Court of Justice’s case law.Footnote 48 According to the court’s case law, “it is for the Member States to ensure judicial protection of an individual’s rights under Community law,”Footnote 49 and to provide for adequate remedies to challenge national acts falling within the scope of EU law.Footnote 50 Hence, as far as a transnational administrative act enforces EU law, it is necessary to guarantee effective access to a court, as well as access to a court which may be fully competent to review this act.

The transnational dimension of the administrative action may create obstacles to the enforcement of such principles due to the involvement of multiple State legal orders and national courts. In particular, two kinds of difficulties may be identified in this respect.

First, there may be situations in which several courts may be regarded as having jurisdiction over an administrative act. In these situations, the question arises as to whether only one court is competent to hear the case, or if the applicant has a choice. The opposite situation may also occur—when no court considers itself competent to review a transnational administrative act—for example, if the action is considered as inadmissible in a given legal order.

Second, with respect to transnational administrative acts, the exercise of the right to an effective remedy is still generally conditioned upon overcoming a number of legal and practical obstacles.Footnote 51 Obstacles which may relate to the conditions for standing and the capacity to act in a given legal system. In this respect, it is essential that persons of foreign nationality—including a foreign public authority—be allowed to bring an admissible action before a court. Concerning this question, the French Conseil d’Etat has, for example, accepted that a foreign State may refer to it a decision refusing extradition.Footnote 52 In addition, practical obstacles be ignored, such as language issues, questions of access to the law, and to knowledge of legal remedies. This includes the identification of the competent court in a foreign system. If the transnational decision falls within the scope of EU law, the EU principle of non-discriminationFootnote 53 is also relevant when the question of access to court is at issue. On this ground, discrimination on the grounds of nationality among the applicants is forbidden.Footnote 54

When transnational administrative decisions are issued in the context of the implementation of EU law, secondary EU legislation might provide an answer to the question of the competent court to review a transnational administrative act. For example, under Regulation No. 2016/679 (GDPR), Article 78(3) states that, “[P]roceedings against a supervisory authority shall be brought before the courts of the Member State where the supervisory authority is established.”Footnote 55 The regulation sticks to a classical vision of territoriality, according to which the administrative acts of a public authority can only be challenged before a court belonging to the same legal order. This regime has the advantage of avoiding any competition among national courts, as it provides for the designation of only one national court. Nevertheless, such a legal regime, solving in advance the potential conflicts of jurisdiction in cases of transnational administrative acts, exists only in limited cases. Most often, such jurisdictional conflicts need to be solved on the basis of national law.

As a matter of principle, and because there is only limited EU harmonization in the field of procedural administrative law, the procedural conditions for the enforcement of EU law at the national levelFootnote 56 on the basis of the principle of institutional and procedural autonomy,Footnote 57 are defined by each national system. As there is a risk that this system might bring about discriminatory treatment between applicants in different Member States—depending on the national court before which an action is brought—national procedural autonomy has been limited by the principles of effectiveness and equivalence. According to the former principle, the procedural conditions at a domestic level may not render excessively difficult or impossible in practice the exercise of rights derived from EU law. The principle of equivalence instead requires that procedural conditions applicable to claims based on EU law may not be less favorable than those applicable to purely national claims.Footnote 58

These principles also naturally govern the question of judicial review of transnational administrative acts when these acts are taken in implementation of EU law. More precisely, in the context of EU law, the principle of territoriality of administrative law may be subject to limitations or at least, adaptations, in order to ensure compliance with these principles.Footnote 59 The next section will examine the extent to which European law, as interpreted by the European Court of Justice, provides solutions and ways of balancing the territoriality principle with the right to an effective remedy.

D. The Extent of Review of Transnational Administrative Decisions

Following the typology of transnational administrative acts provided above, the question of the judicial review of these acts shall be distinguished according to whether the transnational decision is without or with transnational imputation.

I. Judicial Review of Administrative Acts Without Transnational Imputation and with Transnational Effects

As mentioned above, a transnational administrative act without transnational imputation may either be a “pure” national administrative act, or an act with transnational effects. Leaving aside the typology of “pure” administrative acts, where no questions of transnationality arise, this section will examine the possible gaps of judicial protection arising in cases of acts which have transnational effects, but lack transnational imputation.

The starting point for the question of judicial review and the competent court in such cases is the territoriality principle. The basis of this principle is that judicial review of administrative acts can only be carried out by the court of the legal system from which the act emanates.Footnote 60 In the case of administrative acts with transnational effects, this principle will, however, entail the disconnection between the legal system in which the act has been adopted and those in which the act will effect.

This type of administrative act can be challenged in several ways. First, it may be challenged through the usual avenues foreseen for non-transnational administrative acts—the Court of the system from which the act originated—because, from the perspective of the legal system of origin, the administrative act is not transnational. In this case, there is no gap of judicial protection, and the principle of territoriality does not constitute an obstacle to the exercise of the right to an effective remedy, but rather a safeguard for it. From the perspective of the individual claimant, however, while the transnational nature of this administrative act does not constitute a radical obstacle to the exercise of the right of access to the court, it can make it more complex—as it will entail the initiation of a claim in a foreign legal system.

Second, another option for access to the courts would be to bring a claim against the transnational administrative act in the receiving state. This would be done if and when the authorities of this state adopt an act based on the effects of the transnational act, such as an act of recognition or of execution. In these cases, the transnational administrative act is part of a decision-making process of adoption of an act by the receiving state. The latter is thus, from the perspective of the receiving state—an administrative act with transnational imputation. The question of the gaps of judicial review in the context of acts of transnational imputation is the subject matter of the next section.

II. Judicial Review of Transnational Administrative Acts of Transnational Imputation and with Transnational Effects

The difference with the hypothesis discussed above—administrative acts with transnational effects, but without transnational imputation—lies in the fact that when an act is of transnational imputation, the national decision which may be challenged directly before the competent national court is based on factual or legal elements, or even a decision adopted in another legal order by a foreign public authority. From this perspective, the decision may be regarded as a composite decision—a decision adopted following different stages which are split among different national legal orders—that depend on different acts and decisions by national authorities belonging to various legal systems.Footnote 61

Additionally, in such cases, in accordance with the territoriality principle, the court is, in principle, not allowed to directly review a foreign act. A strict understanding of this principle has the effect of granting jurisdictional immunity to this act in the receiving legal system.

One possibility to fill this gap of judicial protection might be to allow an indirect review of these foreign acts. The system of indirect control of legality allows the claimant to challenge the act that constitutes the legal basis for a decision which is the subject of a direct challenge. In such cases, the powers of the court are generally more limited than in a direct action. The act indirectly challenged may typically only be “set aside” inter partes and not annulled erga omnes.Footnote 62 If applied to the context of acts of transnational imputation, one might envisage a solution on the basis of which the court of the legal order adopting the final act may not be in a position to question the validity of a foreign administrative act, but only its effects in its domestic legal order. In the specific context of EU law, the presence of European Union rules applicable to the case might be seen as the trigger to open up the possibility for the court of a Member State to assess the legality of an act in a different Member State. The principle of loyal cooperation, on the basis of which all national courts are responsible for the correct enforcement of EU law, might allow—or possibly even require—these courts to review foreign acts for compliance with the applicable EU framework.

In a limited number of rulings, the European Court of Justice was asked to provide for solutions concerning the possibility of indirectly challenging foreign administrative acts adopted in the course of a horizontal composite procedure. In those cases, the European court was called to weigh two fundamental principles of EU law against each other. On the one hand, the immunity of the act from judicial review in the receiving state can be regarded as being required by the principle of mutual recognition. This principle says that a decision adopted in one Member State shall produce an effect, without any additional control in any other Member States.Footnote 63 On the other hand, the principle of effective judicial protection calls such a solution into doubt, because it would limit the possibility for judicial review by forcing the claimant to go before the court of the legal system of origin of the act. This would potentially create difficulties accessing the court, especially if the act is of a preparatory nature and therefore unlikely to be reviewed by that court.

The first of the relevant rulings adopted in this respect is Berlioz, a Grand Chamber decision.Footnote 64 In this case, the French tax authorities had sent the Luxembourg tax authorities a request for information concerning Berlioz under Directive 2011/16.Footnote 65 Following that request, the Director of the Direct Taxation Administration of Luxembourg took a decision in which he stated that the French tax authorities were verifying the tax situation of Cofima, a subsidiary company of Berlioz, and needed information in order to be able to decide on the application of withholding taxes on the dividends paid by Cofima to Berlioz.Footnote 66 In that decision, the administrative authority, on the basis of Luxembourg domestic law, ordered Berlioz to provide him with certain information.Footnote 67 The company complied with this requirement, with the exception of some information which it did not consider relevant within the meaning of Directive 2011/16 for the control carried out by the French tax authorities.Footnote 68 The Luxembourg administrative authority imposed on Berlioz, on the basis of national law, an administrative fine of 250,000 Euros because of its refusal to provide the required information.Footnote 69 The decision was challenged by the company, which asked the Luxembourg court to review the merits of the decision—as the decision was based on the request made by the French national authorities.Footnote 70 The central question posed to the Court of Justice concerned the scope of the control that could, and even should, be carried out by the Luxembourg court—especially with respect to whether the lack of relevance of the requested information could be contested, which would call into question the French request with regard to EU law and the requirements of Directive 2011/16.Footnote 71 For the purposes of this Article, it should be highlighted that the Luxembourg decision is an act of transnational imputation, because it has its raison d’être in the French authorities’ request.

In the ruling, one can identify two opposing lines of reasoning to determine the extent of jurisdiction of the Luxembourg court to review the French decision. The first is based on the obligation of cooperation which exists—on the basis of the Directive, between the national authorities—and also because of the principle of loyal cooperation, enshrined in Article 4 TEU, which applies to both European and national authorities.Footnote 72 The principle requires that European and national authorities, as well as national authorities amongst themselves, cooperate in good faith in adopting and implementing Union standards.Footnote 73 Moreover, the principle of mutual trust, a central principle of the internal market, also applies in interactions between administrations, and may imply that an administrative act of an authority of a Member State is not called into question if it is intended to apply and produce effects in another Member State.Footnote 74 From this perspective, the control carried out by a foreign national court may undermine the effectiveness of this cooperation and even be considered as an infringement of the obligation of loyal cooperation.

The second view is based on the right to effective judicial protection, and on the effectiveness of European Union law, especially that of Directive 2011/16.Footnote 75 In this respect, the recognition of the jurisdiction of the Luxembourg court to review the decision of request for information adopted by French administrative authorities may be regarded as functional to ensure the correct enforcement of EU law. It is this second conception that ended up prevailing in the Court of Justice’s approach. The Court recalled that, on the basis of Article 20(2) of Directive 2011/16, the requested authority, in this case the Luxembourg authorities, is obliged to check the regularity of the request for information and must verify “that the information sought is not devoid of any foreseeable relevance having regard to the identity of the taxpayer concerned and that of any third party asked to provide the information, and to the requirements of the tax investigation concerned.”Footnote 76 Consequently, the Luxembourg court was considered empowered to review whether the Luxembourg authorities complied with this obligation imposed by secondary European Union law.Footnote 77 Moreover, in order to guarantee the right to an effective judicial remedy, deriving from Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, the national court “must be in a position in which it may carry out the review of the legality of the request for information.”Footnote 78 Hence, the Luxembourg court was considered competent to indirectly review the administrative act adopted by the French authorities, because it constituted the basis of the Luxembourg decision which was the direct subject matter of the claim. Additionally, it was found competent as, the review of legality was made in relation to an EU norm, and not in relation to national law. Thus, such judicial control does not lead to making the validity of an administrative act conditional on compliance with foreign standards. Such a solution, which aims to guarantee the right to an effective remedy, also contributes to reinforcing the effectiveness of EU law—in the case of Directive 2011/16, a fundamental task of national courts under European law. The innovation brought by the Berlioz case is the extension of the obligation to ensure the full effect of EU law, even where the infringement of an EU norm is the act of an administrative authority of another Member State.Footnote 79

In the more recent Donnellan case,Footnote 80 the Court of Justice confirmed that national courts are competent to review not only the substance of foreign administrative acts, but also their compliance with procedural requirements. Such a solution might seem rather self-evident, because substance might be regarded as more sensitive than procedure with regard to the discretion of national competent authorities. In the context of EU law, however, substantive aspects are typically the object of a harmonization process, whereas procedural requirements are left to national law, in accordance with the principle of procedural autonomy. The ECJ ruling is interesting because the European court specifies the conditions under which the principle of territoriality and the principle of mutual trust, on the one hand, and the right to an effective remedy, on the other hand, may be reconciled. The case dealt with the enforcement of Directive 2010/24 concerning mutual assistance for the recovery of claims relating to taxes, duties and other measures,Footnote 81 and especially its Article 14. The applicant, Mr. Eamonn Donnellan, an Irish citizen, challenged before an Irish court the recovery of a claim consisting of a fine imposed on him by a Greek customs authority.Footnote 82 In accordance with the Directive, Greek authorities had asked the Irish competent authorities for assistance in recovering the fine. The Irish authorities considered that they were, on the grounds of the Directive, required to give a positive response to the request for recovery and to proceed with enforcement of that request.Footnote 83 Mr. Donnellan challenged the injunction brought by Irish authorities, claiming that he was deprived of his right to an effective remedy in Greece, because he had not been notified of the fine.Footnote 84 In this case, therefore, the point raised was whether the Irish authorities were—in accordance with the principle of mutual recognition—bound to give effect to the request from the Greek authorities, or, conversely if the right to an effective remedy was to prevail, and the Irish authorities were allowed, under EU law, to decline the Greek request.Footnote 85

The Court recalled the importance of the principle of mutual trust, especially in case of enforcement of mutual assistance mechanisms. Even if it stressed the fundamental nature of the right to an effective remedy, the court ruled that:

[I]t does not in any way follow that the acts of the applicant Member State must be capable of being challenged both before the courts of that Member State and before those of the requested Member State. On the contrary, that system of mutual assistance, as it is based, in particular, on the principle of mutual trust, increases legal certainty with regard to the determination of the Member State in which disputes are settled and thus makes it possible to avoid forum shopping.Footnote 86

Such a statement seems to support the enforcement of the territoriality principle and the unwillingness of the Court of Justice to open the possibility to challenge foreign administrative acts before a national court. Indeed, the Court continued by stating that:

[I]t follows that the action which the person concerned brings in the requested Member State, seeking rejection of the demand for payment addressed to him by the authority of that Member State which is competent for the recovery of the claim made in the applicant Member State, cannot lead to an assessment of the legality of that claim.Footnote 87

The Court admitted, however, that an infringement of the right to an effective remedy in Greece could justify a derogation to the requirement of mutual assistance as provided for by the Directive.Footnote 88 As a consequence, the Irish judge was deemed competent to review the legality of the Greek decision to impose the fine.

Thus, the failure of a Member State to provide an effective judicial remedy definitively justifies, as the Court pointed out, the jurisdiction of the court of another Member State to assess the legality of the foreign act and, on the basis of that assessment, the possibility of calling into question the obligation of mutual assistance.Footnote 89 Therefore, while in this judgment the right to effective remedy prevails, the principle remains that, where possible, it is the court of the legal order of the administrative authority that adopted the act that is first and foremost competent.

Another more recent case should also be mentioned, the ruling Etat Luxembourgeois v. B,Footnote 90 which took place in a similar context to the Berlioz judgment. The Court of Justice clarified the scope of the right of access to an effective remedy against decisions of national authorities to request additional information to authorities of another Member State on the basis of Directive 2011/16. The ruling gave the Court the opportunity to confirm the extent of the scope of judicial review in cases of actions against decisions with transnational imputation. It held, in particular, that:

[T]he court having jurisdiction must review whether the statement of reasons for that decision and for the request on which that decision is based is sufficient to establish that the information in question is not manifestly devoid of any foreseeable relevance, having regard to the identity of the taxpayer concerned, that of the person holding that information, and the requirements of the investigation concerned.Footnote 91

Therefore, national courts remain competent to review the ground of the foreign decision at the origin of the request for information.

It is interesting to note that such a solution, allowing for a national court to review a foreign act on grounds of EU law, was also acknowledged by the French Conseil d’Etat. Its case law offers interesting examples,Footnote 92 even if the rulings are not always very clear. In the Forabosco case,Footnote 93 a French administrative court examined the legality of a decision refusing entry into French territory. That decision was based on a SIS alert, according to which the national authorities are bound to refuse entry to their territory to a third-country national who is the subject of such a request.Footnote 94 Nonetheless, in that judgment, the supreme administrative court held that it had jurisdiction to examine the reasons for the Italian decision, in particular whether the applicant constituted a threat to public policy justifying his entry.Footnote 95 It pointed out that:

[I]t is for the administrative court, when hearing submissions against an administrative decision based on an alert issued on a person’s alert for the purpose of refusing entry, to rule on the merits of the plea that the alert is unjustified even though it has been issued by a foreign administrative authority.Footnote 96

This solution was confirmed by the Catrina ruling,Footnote 97 which held that the administrative courts are not competent to assess the legality of the decisions taken by the national authorities which may have led to the registration of the applicant in the SIS. Thus, they cannot review the lawfulness of the procedure for adopting the foreign administrative decision refusing access to the territory which was adopted according to national procedure. In concrete terms, what the court reviews is the existence of facts or legal decisions which make it possible to identify the existence of a threat justifying entry in the SIS file. Admittedly, such a position may be regarded as calling into question the principle of mutual trust, which would imply recognizing immunity to foreign decisions. Thus, the Forabosco and Catrina judgements bring forward a distinction in the scope of competence of the national court to review indirectly a foreign administrative decision. If the plea relates to the grounds of the decision, which are then based on secondary EU law, the court has jurisdiction. On the contrary, if the plea concerns the adoption procedure, which is usually not provided for in EU law, the national court has no jurisdiction. Interestingly, this distinction is the same as the one drawn by the Court of Justice in the Berlioz and the Donnellan rulings. What emerges from this distinction is that the scope of the national court’s competence to indirectly review a transnational decision is conditioned by the content and scope of secondary EU law.

Finally, in a recent ruling, R.N.N.S. and K.A.,Footnote 98 the Court of Justice confirmed the extent of national courts’ jurisdiction to assess the legality of acts with transnational imputation. In this case, the decision to refuse a Schengen visa was grounded on an objection raised by another Member State.Footnote 99 The Court concluded that, while a national court is competent to review the legality of the decision to refuse a visa, the same court is not competent to review the substantive legality of the decision of objection, which is the ground for the national decision to refuse a visa.Footnote 100 The court’s control is instead limited to verifying “that the procedure of prior consultation of central authorities of other Member States described in Article 22 of the Visa Code has been applied correctly, in particular by checking whether the applicant was correctly identified as the subject of the objection at issue, and that the procedural guarantees, such as the obligation to state reasons referred to in paragraph 46 above, have been respected in the case in question.”Footnote 101 The review of the substantive legality of the objection decision falls instead within the jurisdiction of the courts of the State that raised the objection.Footnote 102 Such an option does not affect the right to an effective remedy. The Court notes that a direct appeal may be exercised before the court of the legal system to which the authority which issued the objection belongs, it will allow a full review of the legality of the decision.Footnote 103 As pointed out above, such a solution does not deprive the individual of access to the court, but may make it more complicated to enforce in practice. An added value of the ruling is to strengthen the obligations imposed on the administrative authorities to ensure that the addressee of the decision to refuse a visa is informed of the available means of appeal.Footnote 104

Through its case-law, the Court of Justice has thus contributed to clarify the means of access to judicial review in cases of an act of transnational imputation and with transnational effects. The Berlioz ruling has opened up the possibility for the national court to review this type of act when grounded in European Union law, and has clarified that a national court should be able to review, indirectly, the conformity of a foreign act which serves as a basis for the national decision. Nevertheless, recent rulings confirm the existence of certain limits to the competence of the court in the indirect review of foreign administrative acts. On the one hand, the scope of the court’s jurisdiction varies according to the degree of precision of secondary Union law. Thus, the review of compliance with procedural requirements is conditioned by the scope of the relevant European legislation. On the other hand, the review of the grounds, which result from a foreign administrative act, depends on the discretion of the national authorities. As such, in the recent R.N.N.S. and K.A. ruling, the limitation of the scope of the national court’s review may be explained by the fact that the national administrative authorities have, under the Schengen Code, a wider discretion when objecting to the adoption of a visa. In contrast, the national administrative authorities had less discretion as seen in the Berlioz judgment, on the basis of Article 5 of Directive 2011/16, where the requested authorities have an obligation to transmit requested information.Footnote 105

E. Conclusion

While transnational administrative acts are not new, the context of European integration has sketched a new scenario with respect to those regulatory mechanisms, which requires the re-thinking of ways to construct the system of judicial review. The determination of a competent court, as well as the scope of review, cannot be designed according to the classical conflict of laws rules resulting from private international law.

On the one hand, the territoriality principle must be taken into account for the determination of the competent court in case of judicial review of transnational administrative law. On the other hand, the application of this principle ought not to affect the right to an effective remedy protected by both the ECHR and the Charter of Fundamental Rights alike. We claim that the softness of the borders of administrative action requires the softening of those surrounding the system of judicial review. The transnational nature of an administrative act ought not to render it immune from judicial review, if compliance with the requirement of Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights is to be ensured.

In the case of administrative acts without transnational imputation, but with transnational effects, a direct action for judicial review before the competent court of the legal order which adopted the act could offer an adequate answer. Its concrete enforcement might face obstacles, however, because it may imply for the applicant the need to bring an action before the court of a foreign legal system. With respect to transnational acts with transnational imputation, EU law provides for solutions grounded on a balance between mutual trust and right to an effective remedy. What looks decisive to solve the issue of judicial review is the existence of common rules, in this case of EU origin, which can be used as a benchmark to review the legality of transnational decisions,Footnote 106 and which can open opportunities for the court to review a foreign administrative act.

Clearly, the development of horizontal composite administrative procedures leads to an extension of the responsibility of the national courts for the correct application of EU law at a national level, which must be understood as no longer being limited to the framework of its own legal order. Nevertheless, the solutions developed by the Court of Justice, while trying to ensure the respect of the right to an effective remedy, may create other issues, such as the possibility that several courts might consider themselves as having jurisdiction over an administrative act. While indeed the Court of Justice has accepted that—in the system of integrated administration created by EU law—an administrative court may review a foreign act which constitutes the basis for a domestic act, this solution does not prevent the court of the legal order adopting the act from reviewing its own domestic acts. Such a solution may, at first sight, look rather favorable to the applicant, as it provides for several fora of judicial review. Nonetheless, it also creates a risk of potential contradictions in the assessment of legality of an administrative act. Some scholars have advanced the idea of horizontal preliminary ruling proceedings as a solution able to reconcile the interests of the applicants and the preservation of the competence of national courts and bring more clarity in the division of jurisdiction between different courts.Footnote 107 The ever-closer cooperation between national administrative authorities within the European Union might mean strengthening the channels of cooperation between the judges competent to review their action. The R.N.N.S. et K.A case seems to show that one way to fill possible gaps in judicial review of transnational administrative act will be found in the procedural deepening of the mechanisms of administrative cooperation—with the administrative authorities having to become more involved in the anticipation of subsequent litigation challenges.

Table 1: Typology of transnational administrative acts