A. Introduction

International investment law is a peculiar construction. Of all systems in international law, it has the largest corpus of underlying treaty instruments, more than 3400, which can appear to the casual onlooker as a vast and heterogenous system of law. Its pluralism is further exacerbated by an ad hoc system of arbitration for each dispute—in which there is no central adjudicative authority or regulative body. Yet, and contrariwise, actors within, and observers of, the system describe it in the singular—international investment law.Footnote 1 Thus, while from a legal positivism standpoint the system is designed to be fragmented, and is formally implemented as such, any outsider reading an arbitral award, attending an academic conference, or discussing the topic with a practitioner or civil society organization would be left with the opposite impression.

The contrast between state design, a pluralistic and decentralized system, and general discourse, an increasingly centralized system, is the subject of a rich doctrinal literature that seeks to analyze the nature, desirability, and extent of such fragmentation in investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).Footnote 2 Moreover, recent empirical and computational work indicates that the system is slowly but gradually converging on some indices.Footnote 3 However, the central focus in this article is on which actors have generated centripetal and converging tendencies in international investment law: It asks who wields influence and why? Some scholars have suggested that this convergence is not necessarily because of treaty changes initiated by the states, but rather a result of the evolving body and the culture of arbitral practice. This perspective suggests that actors within the system are central, which raises socio-legal questions as to the nature of such influence.Footnote 4

There are thus two overall aims of this article. First, by examining the question of convergence, it seeks to establish the extent of actors’ influence on the system. Second, if actors can exert significant effects on the system, which theories could explain their behavior and motivation in doing so? To be sure, the article will only seek to gauge the extent of convergence in certain areas of international investment law, but the focus will remain nonetheless on the relevant actors.

In operationalizing these questions, I have chosen to focus on text-as-data analysis. As the body of practice is developed by the actors involved in litigating the cases, it should be possible to observe indications of change in their written output. To identify these movements in text, I utilize two computational methods in the empirical assessment. Using a large full-text analysis of ISDS documents, I analyze four areas in which change is likely to occur. I investigate first how the actors’ treatment of three issues—environment, human rights, and social responsibility—have changed over time. These areas of legal practice have seen significant development in ISDS over the last two decades, but less so in treaties and especially in treaties subject to arbitration. This is followed by a focus on actors’ legal method, with a study of how actors’ citation practices have changed over the last two decades, which provides a means to bind disparate treaties together in a seemingly coherent jurisprudence.

The article proceeds as follows. Section B discusses previous scholarship on change and fragmentation in ISDS, together with judicial behavior, as well as more general behavioral models that illuminate how and why actors may be enticed to alter their conduct. Following section B, section C describes the methodology and pitfalls of the computational approach. Finally, the results of all four areas of investigation are discussed and analyzed in section D in light of the theoretical framework.

B. Theoretical Perspectives on Actors and Behavior

In his 2009 book, Stephan Schill develops a theory on the multilateralization of international investment law,Footnote 5 which Mary Footer summarizes as follows:

Schill’s concept of multilateralism rests on the idea that the rules and standards of investment protection, found in a plethora of BITs and similar investment instruments, that is, the full spectrum of IIAs, have become generalized and apply equally to all participating actors, irrespective of their two-party provenance in a BIT or another investment.Footnote 6

Schill thus sees a common thread through all components of the ISDS system. From treaty language and the use of the most-favored nation (MFN) clause, to the panel’s use of jurisprudence, and the multifaceted and decentralized design of ISDS, the system converges and tilts inevitably, naturally and even if paradoxically, towards a more monolithic structure.Footnote 7

In his 2017 article, Wolfgang Alschner completed a thorough empirical investigation into how investment arbitration affects the formal development of investment treaty law.Footnote 8 He finds that case law does indeed have a traceable effect on investment treaty design, and that states appear to “repair” their treaties when unfavorable awards are handed down.Footnote 9 Although these “repairs” may also tilt away of general convergence, the fact that states are individually adjusting their treaties may have a pluralizing effect. The same applies to arbitral behavior. Alschner has conducted several analyses of how historical sociology of the investment treaties and subsequent ISDS arbitration has cross-pollinated through language and networks.Footnote 10 In his citational analysis paper, he finds that tribunals who understand their mandate “as ensuring the correct interpretation of the treaty litigated,” will cite less and more precisely than a tribunal “adapting a system wide approach.”Footnote 11

Schill’s and Alschner’s perspectives lead to this article’s departure point. If we accept the notion that treaties should be interpreted independently and in accordance with Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), we should expect that the developments in future treaties, or jurisprudence outside a given treaty, should not significantly influence the written output of actors in adjudication. Yet, any reader with experience within the ISDS system will recognize immediately that this does not reflect the practical reality of much of the system.

In considering who influences change, the anatomy of the ISDS system can be dissected in diverse ways. Arbitration consists of two main groups. The first serve as parties, namely private investors as claimants and sovereign states as respondents. Addressing the disputes is the second group of individuals filling the roles of arbitrators, lawyers, and facilitators of the proceedings. In theory, given the ad hoc nature of ISDS, we might expect the answer to the question of who exercises influence to be the many and diverse actors. However, in practice, the two groups vary dramatically in their level of engagement in the system. While most investors only appear once, and with some notable exceptions, states appear only once or twice a decade, the second group is constituted by many recurring actors, a core of leading arbitrators, lawyers, and arbitral-institutions.Footnote 12 Thus, it seems appropriate to focus on repeat professional actors, rather than parties, in seeking to identify who influences the overall development of the system; and focus on whether and how these repeat actors play an actual role in developing the system.

This article also analyzes the factors that could conceivably steer the individual actors in a given direction. In particular, we can ask whether this is an individually-driven process that springs out of a strategic choice or if such movement is better explained by institutional mechanisms. The scholarship on judicial behavior may shed some light on how actors shape the systems they are working within. Judicial behavior has been studied broadly over the last century or so, ranging widely from analyses of panel composition, age, gender, nationality, and to the length of time since the judges had their breakfast.Footnote 13

There are several reasons for postulating that the system, with certain arbitration actors in the lead, may converge over time. The first is strategic behavior. Todd Tucker, through in-person interviews with forty-three arbitrators, analyzed the collegial patterns between them.Footnote 14 In his 2016 article, Tucker found that arbitrators tend to use their relationships strategically to achieve the outcomes they desire. One particularly interesting comment by an arbitrator concerns how chairs will avoid “pissing off” wing arbitrators to avoid being “bad-mouthed” in the future.Footnote 15 This pattern of behavior has been previously discussed in literature, both broadly from a sociological perspectiveFootnote 16 and closely through an analysis of how such loyalty and networks may influence decision patterns.Footnote 17 At a summary level, this research on inter-arbitrator strategy indicates how networks and collegiality can influence how arbitrators act. Moreover, given that double hatting, a practice where the same individual has more than one role—lawyer, arbitrator, witness, or expert—at any given point, is frequent within the system,Footnote 18 and as pool of repeat actors is smallFootnote 19 and often connected to a small number of key law firms,Footnote 20 such analyses could be extended to counsel as well. One low-cost tactic to maintaining good relations may then be to accept the colleague’s legal analysis without significant challenge. As the colleague’s analysis may have originated under another treaty on another case, this may gradually cause system-wide convergence as interpretations move across treaties.

A second explanation can be found in the concept of legal integrity. In his 2003 article, David Luban offers further insights into a driver of this mechanism: Dilemmas of integrity in the legal profession.Footnote 21 He defines integrity in the legal profession as the internal logical consistency of thought, rather than simply a matter of moral or legal principle. The legal profession bases itself largely on consistent internal coherence, while legal training and ethics strengthens and encourages such impulses.Footnote 22 Strong integrity is, as Luban argues, not unproblematic, and actors may find themselves locked in legal dogmatism, distanced from the actual concerns that the law was created to protect. In investment arbitration, strong integrity may have an unintended consequence: The arbitrator’s desire to maintain their integrity by being legally consistent across cases, even when the cases are founded on different treaties. A hypothetical example may be in order here. In this case, the term investment: While the plain English reading of the term investment has remained static over the system’s lifetime, the content of the term in ISDS has undergone legal various interpretations and has been subject to much debate and development.Footnote 23 The question then becomes whether it is reasonable for an arbitrator to state that investment is one thing in case A under treaty A and then another in case B under treaty B, effectively contradicting themselves. If an actor in ISDS maintains their strong integrity and avoids systematic inconsistency, they can contribute to a greater convergence of jurisprudence.

A third contributor to convergence may be found in the concept of groupthink, originally coined by Irving Janis in his 1972 book Victims of Groupthink. Footnote 24 Groupthink is a social mechanism where a group of individuals make poorer decisions as they prioritize coherence and harmony within the group, leading to an undue search for concurrence and conformity.Footnote 25 In a recent article, Philipp Günther conducted a survey of the susceptibility of groupthink by international judges.Footnote 26 By analyzing the structure of various international courts and adjudicating institutions,Footnote 27 according to an adapted version of revised groupthink model known as general group problem solving (GGPS),Footnote 28 he found varying areas of susceptibility towards the phenomena. Günther’s study did not extend to international arbitration panels. However, his observations on the World Trade Organization (WTO) Appellate Body could apply to ISDS panels. The elements that contribute risk towards groupthink in the WTO include: Few formal rules on decision making, a collegial culture, comparatively few dissents, and an incentive for unanimity to ensure the legitimacy and enforceability of the decisions. Günther argues that all these factors may contribute towards groupthink. While the WTO Appellate Body is structurally divergent from ISDS, it shares many similarities, such as group size, repeat players, and a loose set of regulations on decision making. If groupthink occurs in ISDS, it may contribute towards greater convergence on two levels. The first, and less influential, is within a single case, where the effects may cause less diverse solutions for the litigation at hand. The second, is if groupthink applies to the actor group as a whole. The system’s operative actors may on a general level seek coherence across cases and treaties, leading to less individualized solutions.

The fourth contributor can be construed as strategic but is decidedly short-term—namely choice fatigue. Choice fatigue is a psychological phenomena where the number of decisions made affect the quality of the decisions.Footnote 29 In a recent study, Daniel Peat explores how international courts, in particular the European Court of Human Rights, may have their decisions influenced by choice fatigue.Footnote 30 In an empirical study, he found evidence that adjudicators, when subjected to a large number of choices, tend to fall back to simpler default solutions rather than to process the issue comprehensively and independently. Political science literature on the same subject in relation to domestic court judges support Peat’s findings.Footnote 31 A similar effect may be hypothesized in ISDS, considering the considerable number of ISDS treaties, each offering its own unique solution to a given legal question.Footnote 32 An actor may be tempted to reuse a well-known solution to a legal problem written by perhaps an influential actor, rather than to develop their own solutions. If the treaty of the well-known solution is different from the one under current litigation, convergence of practice may incur.

A final reason may be heuristics. In a systematic review of reform options for ISDS, Georgios Dimitropolous looks into the effects of cognitive biases and behavioral economics on ISDS actors, and the consequences such systemic psychological factors may have on the design of future ISDS reforms.Footnote 33 Through a comprehensive review of literature in both the spheres of legal psychology as well as behavioral economics, he argues that arbitrators and other ISDS actors may be susceptible to a wide range of common cognitive biases. While a full discussion of the potential biases is beyond the scope of this article, it is important to highlight two concepts deployed by Dimitropoulos: Anchoring and framing. Both phenomena reflect how initial and existing information patterns that are available to the actor at an early stage creates a cognitive framework that future information is influenced by, and that subsequently influences new decision making and information processing.Footnote 34 An example of this can be found in Malcolm Langford’s and Daniel Behn’s analysis of how signals from states may inflect arbitrators’ behavior, triggering them to change their legal practice based on specific or systematic feedback from states on awards.Footnote 35 A crude summarization of their conclusions is that arbitrators do exhibit some sensitivity towards states’ feedback and reactions to their awards. A generalization of this feedback would conceivably act as a framing device and possibly converge practice.

Albeit from different perspectives, these studies provide insights into how system design may potentially affect the behavior of the actors and how these factors individually may contribute to greater convergence of interpretation in investment law.

C. Methodology

I. Research design

The empirical research design in this article is focused on the first two research questions— analyzing areas where convergence may be occurring and, investigating who is influencing this change—in order to provide a basis for a general reflection on why these actors may be exerting such influence. This is achieved by observing diachronically empirical aspects of texts created by arbitral actors that are not directly related to changes in the treaty being litigated. I employ two proxies to track changes in actor behavior: Changes over time in the actors’ frequency of citing other ISDS cases, CitProx, and change in frequency of the actors’ use of key concepts, themes, and innovations that have increasingly been introduced into the scholarly and public discourse, TermProx/TermProxNer. This is achieved by analyzing the full corpus of publicly available documents related to ISDS cases and observing how the velocity of change varies over time.

The two proxies are observed from three perspectives. First, a macro perspective is applied, whereby documents from the major actor groups in the system are analyzed, CitProx-A/TermProx-A. This includes documents from arbitrators as well as counsel for the claimants and respondents. Second, a disaggregated approach is adopted, and each of these groups are analyzed individually, CitProx-G/TermProx-G. Finally, two slightly modified analyses are conducted on individual chairs of arbitrations, CitProx-I/TermProx-I. This final approach illuminates the question of whether change stems from a system-wide institutional evolution or if it is powered by individual actors. The analysis shows, for the first proxy, both the frequency of citation for the individual actors as well as which actors are the most cited.

The use of citational patternsFootnote 36 and textual analysisFootnote 37 are both frequently applied tools for understanding judicial practice and change. As the written material produced in legal cases offers a somewhat concentrated view of the real-life expressions of the different actors’ preferences, I argue that it should also reflect changes in the how the actors interact with the legal framework under litigation. If the written material exhibits variations, it may show a change in the actors’ behavior and perhaps grant us some insight into their thinking.

The proxies each illustrate a facet of how change in actor behavior may indicate how the actors perceive the system’s direction. The first proxy, frequency of citations—CitProx, serves two purposes in this regard. First, when an actor cites another ISDS case, they attribute it with some value to the current case.Footnote 38 This can be legal, informational, symbolic, or argumentative. To be sure, it is important to emphasize that this value can vary vastly in nature, from blatantly disagreeing with the cited jurisprudence to blindly following a precedent set by another case or simply increasing their legitimacy by citing other renowned arbitrators. While a few treaties such as the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and some bilateral investment treaties (BITs),Footnote 39 incur frequent litigation, providing those tribunals with a certain incentive for consistency, even if not bound by precedent. Citations made to cases originating from treaties other than the one being litigated lack formal power.

Observing change in the volume of citations over time provides insight into how the actors’ interactions with each other develop. By observing this volume of citations, I argue that we can understand the parties’ own practical view on whether they treat ISDS as pluralistic or monolithic. Additionally, observing who the arbitrators cite allows us to better understand whether particular individuals or groups are influencing change or if such change is more general in nature.

The second proxy, TermProx, uses keywords and terms to illustrate how actors are being influenced by issues outside of the treaty’s language. In an isolated pluralistic system, the change in influence of innovations and ideas from outside the litigated treaty would be presumed to be limited. If the actors interact with the system under the perception and acceptance that ISDS is converging towards a monolithic state, innovations that start to enter the system through other non-litigated treaties should increasingly be used by the actors. The three concept groups analyzed, namely environment, human rights, and social responsibility, are selected due to their fairly infrequent use and recent introduction into treaties.Footnote 40 While the terms are not found in older treaties, they have been the subject of both academic and civil society discussions in the last decades, and these debates would be well known to the professional actors. To provide a comparative reference point, several long-standing terms such as expropriation, fair and equitable treatment, and damages that have been included in treaties over an extended period of time are also included.

To better understand how and why change is happening, I scrutinize the two proxies from three different perspectives. First, I analyze both proxies from an overall viewpoint, where the system’s actors are grouped together, CitProx-A/TermProx-A. This provides a baseline on how and if the system, as a whole, changes.

Second, I break this down into the groups of actors—claimants, respondents, and tribunals (CitProx-Gc/r/t)/(TermProx-Gc/r/t). This provides an indication of which groups are pushing towards a certain structure, and subsequently, if there are any groups pushing against such change. It will give an indication as to whether or not there is a common understanding of the direction of change among all participants in the system.

Third, I analyze the proxies on each individual arbitrator, CitProx-I/TermProx-I. This should reveal if a particular type of individual, or smaller groups of individuals, are pushing the system towards a given architecture in accordance with their preferences,Footnote 41 or if any such changes occur purely as a result of non-individualized institutional mechanisms. As previously mentioned, I and others have found that a limited set of key individuals, due to their frequent appearances, wield significant influence in the system.Footnote 42

II. Data

The study is conducted inside the PITAD computational research platform.Footnote 43 For this article, I have augmented PITAD with the complete archive of available ISDS documents sourced from the archives of ITA-law.Footnote 44 These are linked with the metadata available in PITAD. Out of 1000+ cases in the database, a little over 500 cases have received an award of which 489 have documents available. The number of documents for a case varies from as little as one document to well over 100. While the large number of pages still available, 250,000+, makes it feasible to extract useful information, it does limit the possibility to draw out anything stronger than preliminary indications.

A total of 4,975 documents form the underlying material upon which the algorithms are developed. Of these, 3,474 documents are attributable to the actors under analysis: 1,971 documents to tribunals, 770 to claimants, and 567 to the responding party. These documents, containing over 250,000 pages, are used in the subsequent analysis. The remaining 1,709 documents are attributed to other actors and processes and are not included in the subsequent analysis. As citations may apply to both procedural and material questions, all document types from the above subset are included. For the key-concept analysis, procedural orders and documents are removed from the dataset as the terms analyzed are of a material nature, and inclusion of procedural documents would incorrectly skew the data. For the citation analysis of individual arbitrators, the selection is limited to awards, as these are the primary documents that can be specifically attributed.

III. Method

To extract and analyze the two proxies, I created a comprehensive computer program that extracts, processes, and tabulates the information from the text of each document.

As illustrated in Figure 1, I created a custom pipeline that parses each document through a series of algorithms,Footnote 45 feeds a program designed for this article that determines the document type, and subsequently, assigns it to its likely author—arbitral panel, claimant, or respondent.

Figure 1. Illustration of how terms and citations are extracted from the underlying documents.

My analytics algorithm follows three paths for extracting the entities for further analysis.

For the first proxy, TermProx, I developed an algorithm that uses named entity recognizers (NERs) to detect a set of pre-selected terms in the documents. A total of 23 terms/spellings are grouped in the three categories.

While the use of pre-selected terms provides useful insights, they are limited by any author’s inability to list every term relevant to a specific subject. Due to the great variance of case subject matter, language, complexity, and detail of any given term, single term selection may not fully grasp the content of the documents. To address this, I expand the algorithm beyond keyword search to a full NER-algorithm, TermProxNer, which is trained on and coupled with the full corpus of Wikipedia.Footnote 46 By using the category structure of Wikipedia, 300 key concepts across the categories were added to augment the terms described above.Footnote 47 A concept in this context incorporates one or more variations of spelling, syntax, and synonyms of a single term. As the NER methodology uses full sentence analysis to extract the terms, the algorithms mostly avoid non-applicable meanings of the words.

As the case matter may influence the usage of the terms, a supporting analysis is conducted by correlating each document analyzed data with the relevant industry sector from PITAD.Footnote 48 A full overview of all documents associated sector, as well as a parallel analysis of the sector of the documents that contain a match for each of the terms, is provided to give context to the analysis. This contextual analysis provides a correcting perspective on the term usage.

To create the citational network for the second proxy, CitProx, a customized machine-learning-based named entity recognition algorithm based on the Spacy libraryFootnote 49 was trained on the manually coded information from PITAD. The model recognizes citations to any ISDS case in the PITAD database. The data is used to establish the citational patterns of the actors. The data is individually analyzed for the three major groups of actors—documents from the tribunals, claimants, and respondents. Using this sectioning, I can distinguish how actor’s behavior differs from each other.

To avoid any biases related to any actor’s intensive use of a given term or citation in any given document, occurrences of any given citation or key term usage is counted once per document. In the group analysis, TermProx-A/G and CitProx-A/G, the data for all paths are subsequently placed on a temporal scale. Due to the limited set of documents available for any given single year, the documents are grouped in five-year intervals. This reduces any effects that a single case may have on the analysis. Because of the varying number of documents available in each period, the results are expressed as a percentage of the available documents rather than in per case occurrences. Further, due to the very slim availability of documents prior to 2000, only the period between 2000 and 2020 are included.

The individual analysis for both proxies, TermProx-I/CitProx-I, follows the same methodology for analyzing and extracting data from the documents; but, due to data availability and proper segmentation, I follow a diverging strategy for temporal and individual assignment. To ensure that documents are fairly assigned to the correct arbitrators, some limitations are added to the selection of data. First, to increase the likelihood of attributing citations and term usage to the correct individual, the analysis is restricted to the chair of each tribunal. While wing arbitrators do to varying degrees make contributions to the final text, it is assumed that the chair bears the main responsibility of drafting.Footnote 50 As such, I argue that we can obtain a better impression of individual contribution to change by assuming that the chair is the primary author. Finally, for both TermProx-I and CitProx-I, five group averages are calculated. These groups are based on a calculation of how influential the arbitrator is in the system. The score, called a HITS-score, is based on an arbitrator’s network influence. This is taken from my earlier work with Langford and Behn on determining the influence of actors within the ISDS system.Footnote 51 The top twenty percent-scoring arbitrators were placed subsequently in the first group and so on. This allows us to test if an arbitrator’s influence and history has an affect on citations and term use.

IV. Limitations and Caveats

Before proceeding, some limitations and caveats should be noted. The intent of this article is not to provide infallible conclusions. Rather, the study is meant to analyze the questions from an empirical perspective to help illuminate the explorative theoretical discussion that follows in the remainder of the article. Due to the inherent inaccuracies in the methodology, this article is indicative rather than conclusive. Nonetheless, such indications may be useful and spur further, more detailed study on the issues at hand.

Five issues prevent any hard conclusions from being made. First, the limitation in available data is the greatest challenge to the validity of the results. While most cases that have been decided have documents, there is limited availability from settled cases and cases that are otherwise discontinued. The variation in the number of documents for each case further promotes caution against arguing too firm conclusions.

Second, this article does not fully isolate the context in which a citation has been made. The algorithm as such does not distinguish between a party following or refusing any given jurisprudence, it will simply state that the given party has made mention or reference to that decision. This issue of context applies similarly to the use of terms and concepts. The use of the term human rights may very well be in the context that human rights are not relevant for this case. While the NER algorithms improve this from a traditional key-word search, computers still have a limited understanding of human language.

Third, there is potential inaccuracy in the underlying NER algorithms. Although the NER algorithms developed in this article are state of the art, their accuracy is limited and both false positives and negatives occur. The accuracy of the algorithms ranges from 90–98%. This is mitigated by limiting the analysis to observe if a document contains a given term at all, rather than trying to identify every occurrence of a term. Given the considerable number of documents though, this limitation should not have significant affect on the results.

Fourth, the case matter itself may skew the use of key words/phrases. In ISDS, certain sectors and world events, like the Argentinean fiscal crisis, may turn the arbitrators’ focus to certain themes that in turn increases the use of certain phrases. While there are indications in the data that this has a non-negligible affect on the data—see analysis in the section below—I argue that this should still be seen as expression of actors and the outside world’s influence on the development of ISDS.

Finally, a temporal caveat requires mentioning. The availability of non-award documents for earlier cases is limited. This may skew the dataset towards later documents, simply by virtue of the larger and more varied corpus for recent cases. In the article, however, I address this partly by comparing proportions and fractions of documents rather than the absolute number of occurrences.

D. Results

In this section, I aim to illuminate any process of convergence and development of investment law on the part of the system’s professional actors. The results show an occurrence of shifts in both citational patterns and the use of key concepts over the four five-year periods.

I. Results – Groups

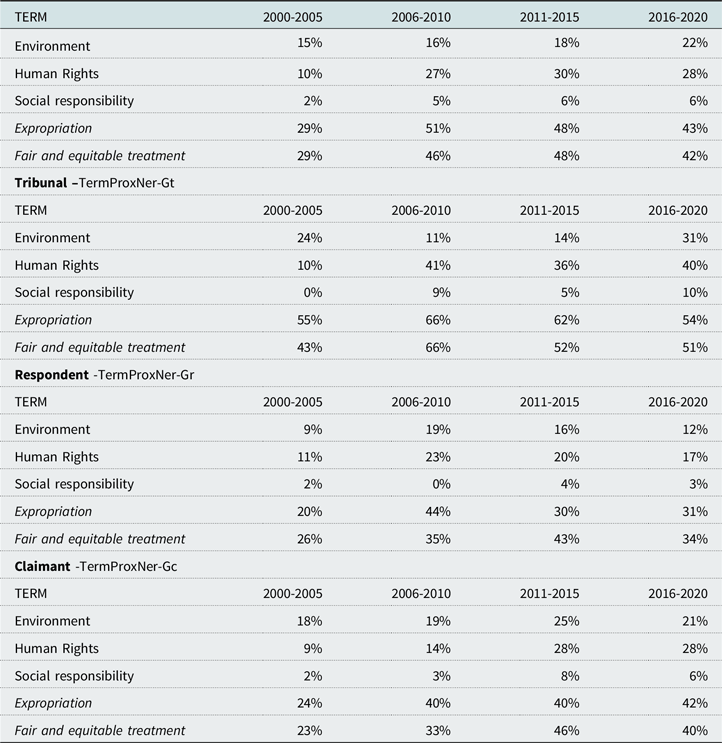

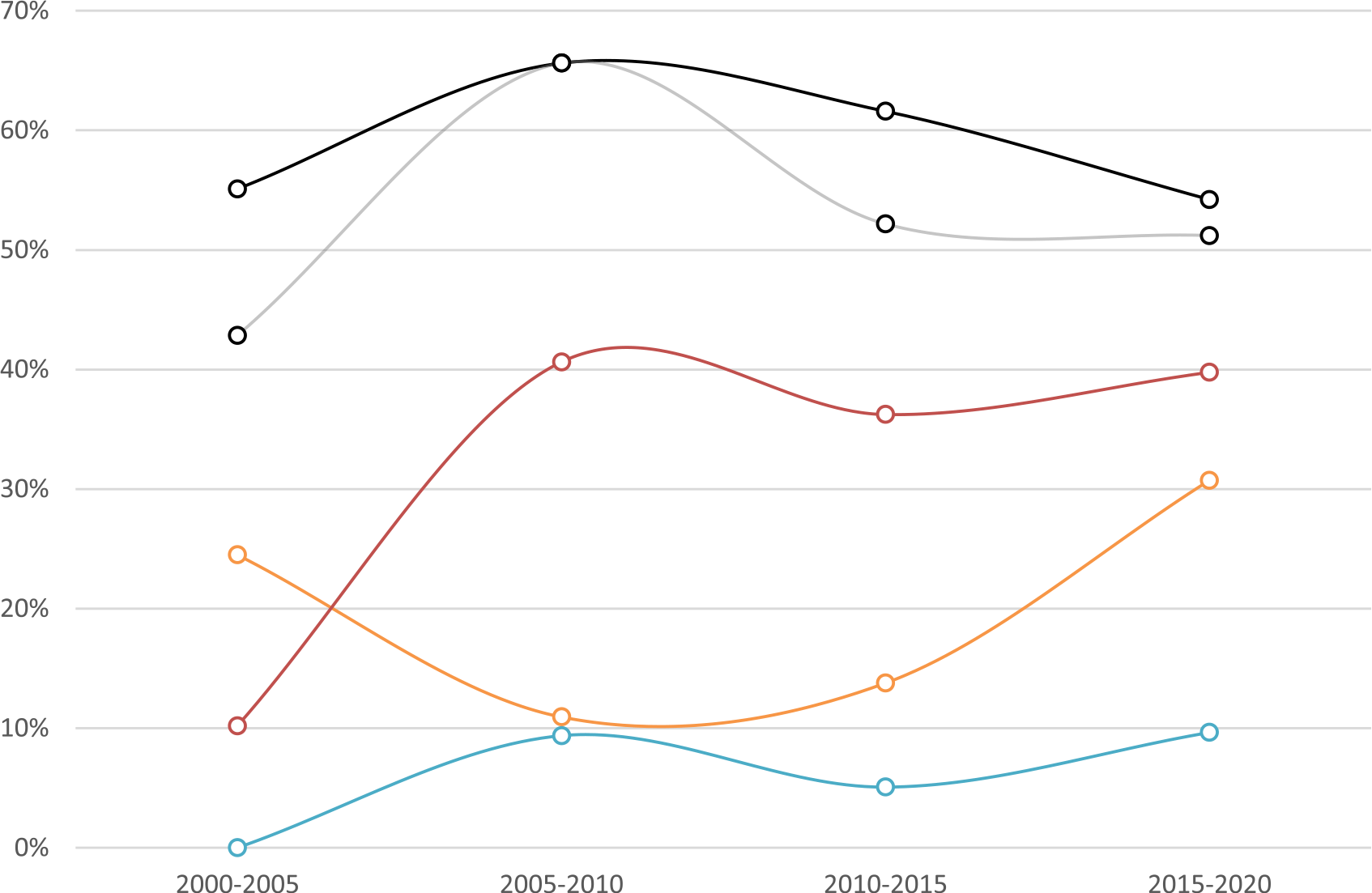

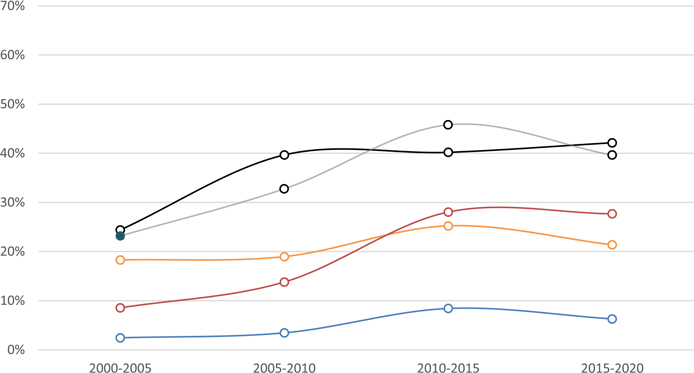

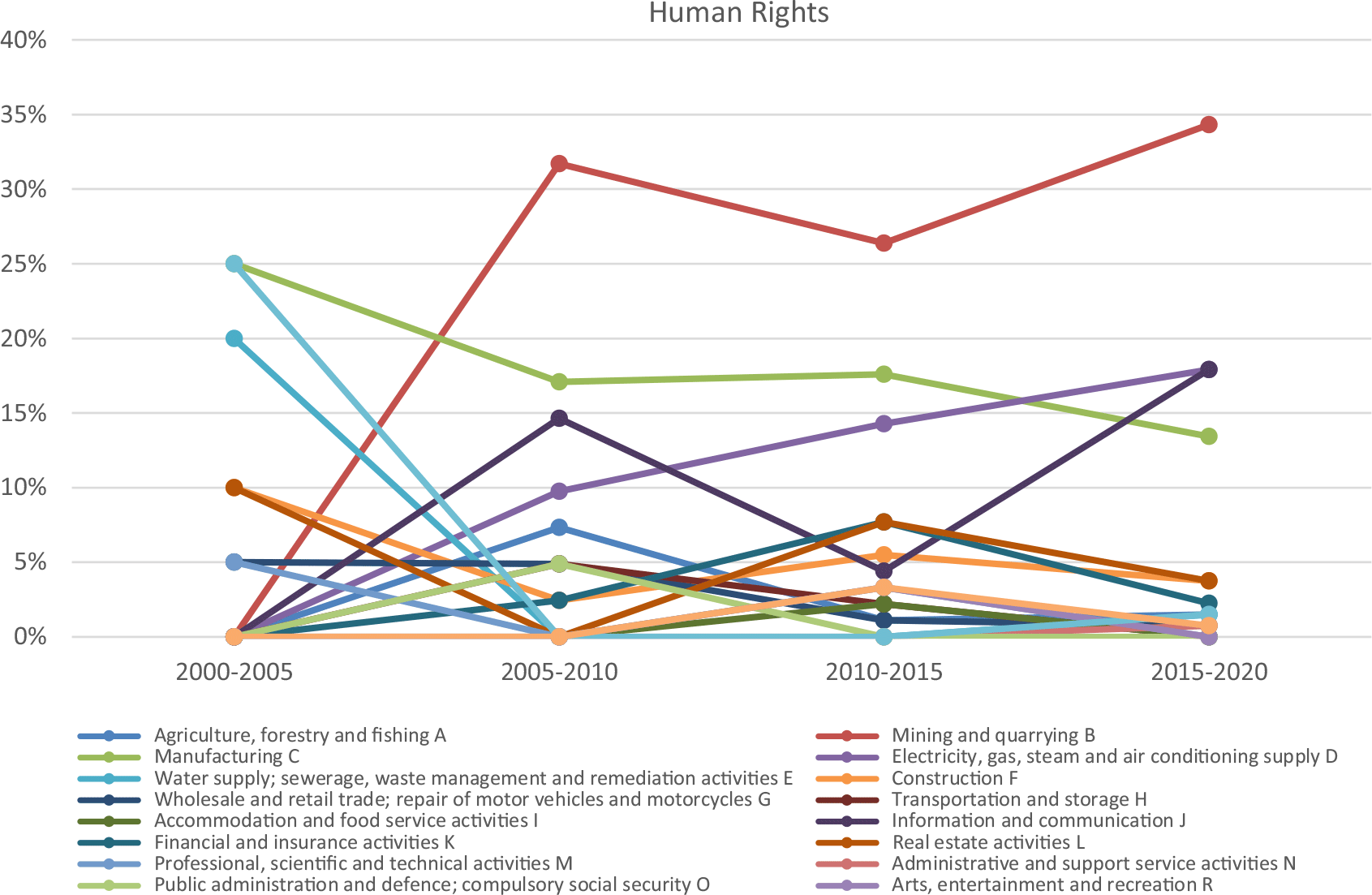

The first results concern the usage of terms and are set out below. Table 1 shows an overview of the frequency of terms analyzed over time. There is an increase in the frequency of use of the analyzed terms across the board. The most frequently cited of the analyzed concepts are those related to human rights. Across all documents and actors, TermProx-A, it initially occurs in ten percent of the case documents in 2000–05 and increases to around thirty percent where it hovers for the remaining periods. While the tribunals’, TermProx-Gt (figure 2), use of the concept sees a quadrupling from ten percent in 2000–05 to forty percent 2005–10, and subsequently hovering between thirty-six percent and forty percent, claimants and respondents see a less dramatic, yet, significant growth. Claimants, TermProx-Gc (figure 3), increase their use of human rights from nine percent in 2000-05 through fourteen percent in 2006–10 before stabilizing at twenty-eight percent. Respondents, TermProx-Gr (figure 4), initially increase their use from eleven percent during 2000–05 to twenty-three percent during 2006–10 before dropping off, ending at seventeen percent in the 2016–20 period. While tribunals appear to increase their use most, the more than doubling of use across the board is intriguing. It should also be noted that the discrepancy may to some degree be exaggerated by the availability of documents.

Table 1. TermProxNer – Results. The items emphasized are for comparative use

All –TermProxNer-Ga

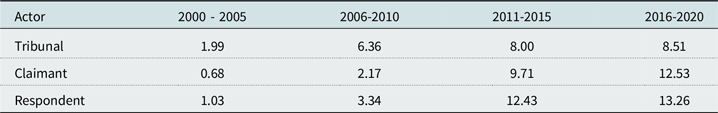

Table 2. Average number of ISDS cases cited per document

In the second results, curiously, a similar pattern is not found when observing environmentally-related concepts. On the one hand, tribunals appear to use these terms in twenty-four percent of documents in the 2000–05 interval before dropping their use to eleven percent and fourteen percent in the 2006–15 range, and subsequently, increasing their use to thirty-one percent in the final 2016–20 interval. Claimants’ use, on the other hand, remains steady at eighteen percent and nineteen percent in the first two periods, increasing to twenty-five percent in the 2011–15 period, and subsequently, dropping back down to twenty-one percent of documents. Respondents, however, appear to have a peak in the 2006–10 period of nineteen percent, up from nine percent in the 2000–05 period, and then dropping steadily back down to twelve percent in the 2016–20 period. While all actors see a small general increase in usage over the two decades, this is far less prevalent than the increases in human rights-related language. This pattern resembles the one found by Langford and Behn in their 2017 study of environmental critiques of ISDS.Footnote 52

The third category of terms, those related to social and corporate responsibility, exhibits perhaps the clearest example of actors’ change in behavior. The tribunals avoid the terms in any document in the 2000–05 period. In the subsequent 2006–10 period, it increases to nine percent. In the 2011–15 period, it drops down to five percent before increasing again to ten percent. Claimants appear to use the term slightly more increasing from two percent in 2000–05, increasing to three percent in 2005–10, topping up at eight percent in 2010–15, before dropping down to six percent. Respondents appear to use the terms less with two percent in 2000–05, zero percent in 2006–10, four percent in 2011–15, and three percent in 2016–20 in the periods. Two observations may be made from this development. First, it illustrates how a new concept may be effectively introduced into actors’ vocabularies, and as such, phase into active use within the system. Second, as with human rights and environmental concepts, we can see how the development while significant is not always stable.

One immediate explanation for increases in the studied terms could be a shift in the case matter.Footnote 53 The graph below shows the fraction of all documents for each sector in the given period. While we can observe a significant increase in cases related to mining and quarrying Sector B—as well as a significant decrease in agriculture, forestry, and fishing—Sector A— the total shifts in case matter does not appear to fully explain the general shifts in attention described above. Figure 5 shows the relative fractions of documents in each period that is related to a given sector, the sector is determined by the underlying case the document relates to. The share of documents related to sector B, mining and quarrying, increase significantly over the period. Likewise, documents relating to sector D, which among other things contain electricity generation, sees a general upward trend before trailing off in the final quartile. Sector C, manufacturing, sees a drop of its share before stabilizing at a fairly high level. Documents relating to sector E, sewage and water supply, and A, agriculture and fishing, both drop in the first half of the studied periods. As we can see from this, there is development in the subject matter, proxied through sector, of the documents that are studied, however, there is no clear correlation with the tendencies in term use.

Figure 2. Terms Tribunal – Red: Human Rights, Orange: Environment, Teal: Social responsibility, Grey: FET, Black: Expropriation.

Figure 3. Terms Claimant - Red: Human Rights, Orange: Environment, Teal: Social responsibility, Grey: FET, Black: Expropriation.

Figure 4. Terms Respondent – Red: Human Rights, Orange: Environment, Teal: Social responsibility, Grey: FET, Black: Expropriation.

Figure 5. The fraction of documents from a given period that belongs to a case of a given sector.

Observing the sectors of the documents in which the terms are used paints a slightly different picture. Across all three groups of terms, sector B, mining and quarrying, is very prevalent in the matched documents. For social responsibility (figure 6), seventy-seven percent of the matched documents in the 2015–20 period is related to cases in this sector. For terms that are related to environment (figure 7), sector B, while still dominant, tops out at a more modest forty-three percent. The situation is more diverse with terms related to human rights (figure 8); however, in sector B, is still a dominant contributor.

The increase of cases in the mining and quarrying sector may have an affect on the general increase in term usage. However, and especially in relation to human rights and the environment, there is enough variation in the sectors that it is difficult to argue that any change in a given sector’s prevalence explain sufficiently the general increases in the use of the studied terms.

As such, it appears that overall ISDS actors are using increasingly new language and concepts. Their focus on environmental, human rights, and social responsibility has increased in the last 20 years.

Similarly, as illustrated in figure 9 I find a large increase in the use of citations for all actors across ISDS. In the analysis, a total of 23,673 citations were identified in the documents. As mentioned in the methods section, multiple citations of the same case in the same document only count as one mention in the dataset. Due to the increase in documents available for analysis, the raw number of citations has increased significantly in the last decade; however, the methodology compensates for this by seeing the number of citations as fractions rather than absolute numbers.

Figure 6. Fractions of sectors where a match for the terms were found.

Figure 7. Fractions of sectors where a match for the terms were found.

Figure 8. Fractions of sectors where a match for the terms were found.

Figure 9. Graph showing how many other cases each actor cites on average.

The number of cases cited by the actors increases continually over the studied periods (table 2). Tribunals quadruple the number of cases they cite on average, from just shy of two per document in the 2000–05 period, up to 8.51 in 2016–20. While tribunals’ use of citations appears to level off after 2010, claimants’ use appears to continue increasing, citing thirteen times the number of cases in 2016–20 than in 2000–05. Respondents see a similar volume increase. However, while claimants keep increasing, the trend for respondents flattens out between 2010–20.

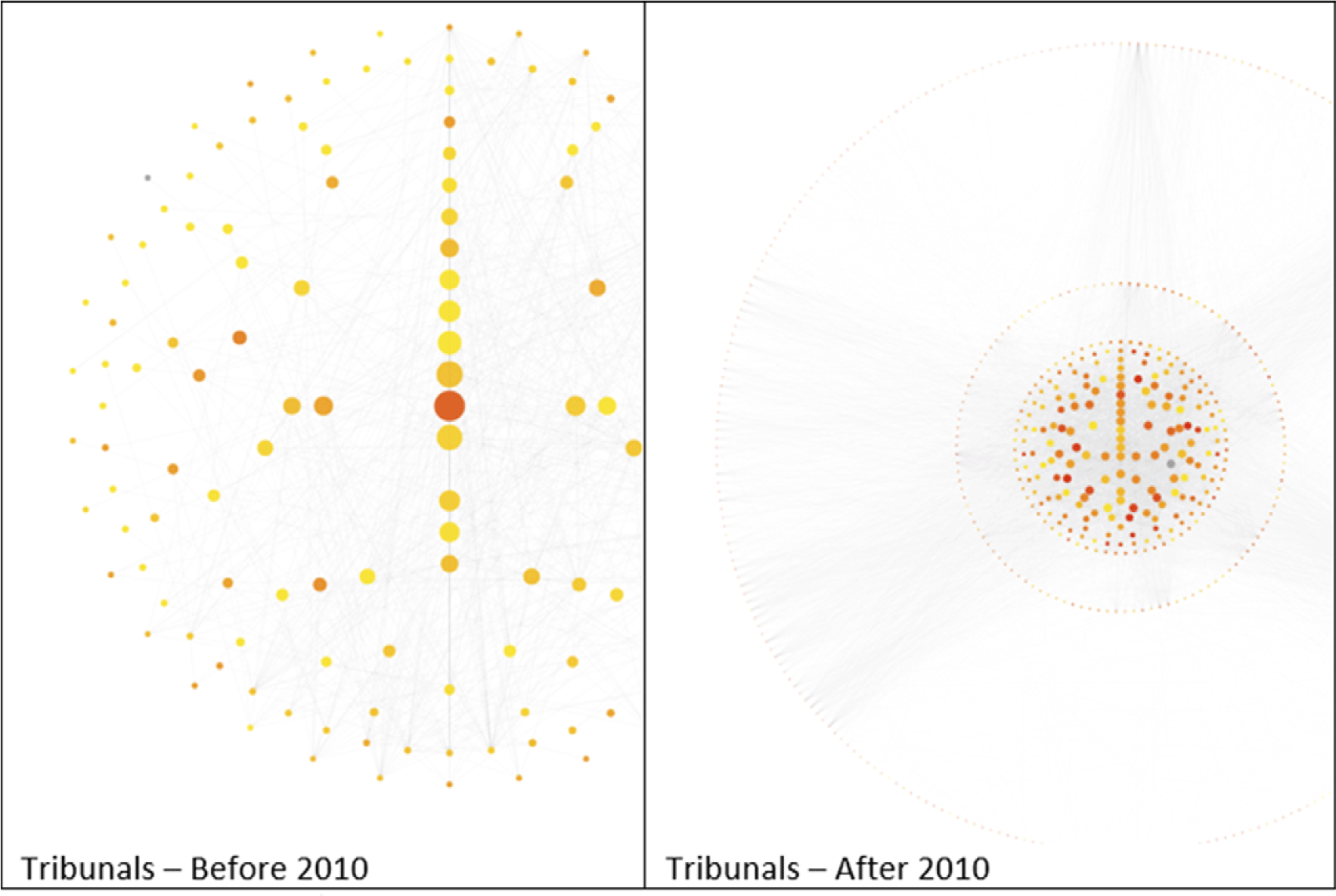

While the results show that the number of citations is increasing across all actors, the illustrations in Figures 10 to 13 demonstrate the complexity of the citational patterns. As more cases are being cited and certain cases are cited with increased frequency, the cross-reference network within ISDS becomes progressively more sophisticated. In the following illustrations, citational patterns before and after 2010 are shown. The illustration is on a case-by-case basis, and only one citation per case is accounted for. The color of the nodes ranges from yellow for older cases to red for the newest ones. The nodes are organized and sized by the number of other cases that have cited them. Larger and more central nodes have been cited more than smaller nodes on the periphery.

Figure 10. Citation pattern for CitProx-A.

Figure 11. Citation pattern for CitProx-T.

Figure 12. Citation pattern for CitProx-C.

Figure 13. Citation pattern for CitProx-R.

Across all actors, CitProx-A, we can observe a fairly complex network of citations before 2010. However, when comparing it to after 2010, the network is much less intricate. Two features are worth closer attention. First, the number of widely cited cases, those close to the center, increases. Second, the sheer number of cases being cited is several times higher. In general, the networks are both denser and larger, the network in before 2010 would fit within the inner circle of the network after 2010.

The main driver of this increase is found in the documents authored by the tribunals. They have a similar pre-2010 pattern as the full group. With a quite comprehensive network of citations, we can see a similar, if slightly lower, increase in complexity of citations after 2010. The density of the latter network is however lower.

The largest change is found in the patterns of citation in the documents attributed to claimants and respondents. Both initially show austere patterns of citations for the first decade of the century. In the second decade, networks increase massively in both number of cases cited, as well as the density of the network. When comparing this to the tribunals’ development, the difference becomes quite stark.

As these two broad-brushed empirical studies show that change is occurring, at least at first glance, it suggests that the actors are treating the system in an increasingly converging fashion.

II. Results – Strategic Individual – or Systemic Change?

As we can see in the previous section, there is a difference in the rate of change between the diverse groups of actors. While it appears that counsel appear to be more active in the final two periods in leading change, arbitrators, who are the ones bearing the final burden of decision, still show comprehensive development in their writing. While it perhaps could be concluded that the litigating parties are the root cause of this evolution, it raises the question of whether this can be attributed to individual actors’ strategic preferences, or if we are seeing more general changes across the board.

Unfortunately, the attempt to analyze the use of terms on an individual temporal level proved to be a less than a fruitful endeavor. Compared to citations that in most cases occur in every document, the occurrence of the key terms is far less frequent, and as such, establishing a timeline for each term-arbitrator pair is not possible.

Turning to citations, when splitting the groups of actors into quintiles, an intriguing pattern emerged among the “runners up” (figure 14). Arbitrators who are ranked from places twenty to forty, in terms of influence, appear to cite twice as much as the preceding and following quintiles. Due to the small sample size, this may just be an anomaly; but, it is tempting to speculate that members of this group are slightly more susceptible to “cite their way up the ladder.”

While the small sample size disallows any firm statements on motivations, the above graph does deserve further scrutiny. Although all arbitrators appear to increase their citations overall, and with some increasing massively, there is little coherence in the sample beyond the “runners-up” group. Within the most influential arbitrators, citational frequency varies as much as within any other group. However, the data for incoming citations, figure 15, that is how many times a given arbitrator’s case has been cited in other cases, it becomes clear that while all groups are increasingly being cited, the top-group’s growth and relative affect is significantly higher. The higher number of cases that the lead arbitrators precede over provides part of the explanation to the increased number of citations. Co-authoring more opinions provides the arbitrator with more chances to be cited than less prolific arbitrators. At first glance, the simple number of cases arbitrated provide a reasonable explanation to the top-groups being cited the most. However, the concentration of cases on a few hands may have a self-reinforcing effect over time. As the top arbitrators have more cases on more matters, and their reputations’ grow through increased citations, this points towards a proposition that they continually increase their ability to shape the system.

Figure 14. Graph showing development in citations for the various groups of arbitrators sorted by influence.

Figure 15. Average number of documents per year the groups of arbitrators have been cited in.

E. Discussion: Why is Change Happening, Who is Influencing Change and What Are the Consequences of Change?

As the data may underpin either a strategic choice or a more system-wide development, I would briefly like to return to the concept of preference. A key topic of debate in investment law is the desire for consistent and predictable outcomes,Footnote 54 and it is conceivable that actors’ preferences could be related to a practical or ideological idea of how the system should be shaped. Investment law inherently has only very weak formal mechanisms for providing such consistent and predictable outcomes. It is feasible that this desire for consistency and predictability may be reflected in actor behavior as well, and consequently, drive up the use of citations for increased consistency.

The consistent individual, group and all-round increases in citations, lends empirical support in two ways to Tucker’s analysis of collegial relations,Footnote 55 especially seen against the backdrop of Yves Dezaly’s and Bryant Garth’s work on arbitrators’ networks.Footnote 56 First, the general increase in citations could indicate that actors overall are using citations as a strategic tool to increase their influence. Second, the significant differences between the arbitrators, and particularly the arbitrators in the first and second tier, could indicate that the ones in the top tier feel less need to cite to maintain or increase their position, compared to those on the second tier.

While the observation of the second quintile in the power-index shows a significantly stronger increase, which in itself may be indicative of an individual strategic choice, the exceptionless and fairly consistent increase points towards broader system-wide mechanisms. There is, however, no reason why both of these may be true as certain individuals or groups could be utilizing citations as strategic devices to gain influence, while others are simply observing and following the trends of the system.

Luban’s concept of integrity might shed some further light on the results. In the last five years of the individual arbitrator citation analysis, we see a close to exponential increase in both citations per documents as well as the fraction of available cases cited. Increased use of citations, particularly if they are used with a goal of influence or consistency, could create an ever-increasing feedback loop, that would require an actor to maintain, or in most cases increase, their citations gradually to maintain the arguments they made in previous cases. Luban’s idea of integrity would as such bind the actor to mast, so to speak. Once they have started citing other cases, they would have to continue to do so. To avoid self-contradiction, it could also be speculated that they would have to serve up consistent argumentation across different cases, again leading to increased citations. Given the small group of arbitrators, this may create self-strengthening feedback-loops that could cause significant systemic effects.

As the data itself provides support for both a systemic interpretation and an individual strategic one, it is possible that both mechanisms could be driving the system towards an increasingly monolithic structure. The data, seen in conjunction with the underlying theory, indicates that from a birds-eye-perspective they work in tandem, influencing each other, and over time, conceivably converging into strong systemic norms.

In the previous sections, I have noted some reasons for the variations in how actor-groups, and individuals, are changing their behavior. Until now, I have looked at the more or less conscious choices that an actor may make to implement what he or she believes is in the best interest of the system: their personal integrity, winning cases, or perhaps advancing their career. In all likelihood, there is a multitude of mechanisms that are all, to some degree, influencing the individual actors. In the following, I will discuss some of the factors that may be less a product of the preference of the actor, but to a larger degree systemic and invisible forces that affect change.

While further studies and a fuller analysis of the susceptibility and effects on ISDS is beyond the scope of this article, it is plausible to speculate that the formally described groupthink or general group solving, may influence arbitrators when actors choose solutions for a legal question. It would be relevant here to point out that due to the small selection of influential actors,Footnote 57 the group may be considered on two levels.

On the first level, the group can be considered as the collection of actors in any given case, including arbitrators and the parties’ legal teams. On the second level, the group may be seen as the larger society of actors in the overall ISDS system. Mechanisms of groupthink may potentially influence both levels. The common and coherent development across the groups may provide a speculative basis for claiming the presence of groupthink within the system. From a common-sense perspective, there is no reason that these groups should be uniquely isolated from such a phenomena. Indeed, and on the contrary, several mechanisms may make it more likely that ISDS actors are susceptible to such occurrences. The data appears to support this explanation. The actors, both as isolated groups, arbitrators/counsel, and as a larger collegium, appear to, in fairly homogeneous manner, increase their use of citations and key terms over time. This coherence indicates that the actors share a common mechanism and/or incentive for adopting common behavior. While the increases themselves may be explained by a general appreciation for the practical benefits of increasing the use of citations in ISDS, the level of coherence and lack of explicit statements of rationale for this increase point in the direction of less conscious motivations. Within a given arbitral tribunal, several incentives may present themselves. The need to avoid unnecessary conflict within the tribunal, imbalance of experience between the arbitrators, and an aspiration for a unanimous award may all be factors contributing towards a desire for cohesion. Seeing the group as the ISDS community as a whole, the combination of strict barriers of entry,Footnote 58 double hatting,Footnote 59 and small groups of key actors,Footnote 60 can all create substantial incentives for cohesion and avoidance of internal conflict.

Observing the large discrepancies in individual arbitrators’ increase in citations may give an indication that choice fatigue may be a factor. Although speculative, it could be hypothesized that individuals react differently, perhaps based on a combination of their experience, legal background, and to varying degrees, experience choice fatigue, and as such, apply the strategy of citations to combat such fatigue. The differences between the different tiers shown in figure 14 and 15 further indicates that experience may be a contributor. In the context of this article, it is natural to see existing jurisprudence, as well as the actors’ previous experience, outside the current treaty and case, to anchor and frame the questions the actor has to address. The capacity required for an actor to escape this framing may further encourage actors, as we can tell from the empirical results, to choose the road more travelled.

The gradual increase in citations, and use of key terms by all actors, may provide further indications of how collegial loyalty may affect legal reasoning. Collegial loyalty may be analyzed across two dimensions. First, it can be interpreted in a purely local sense, as in one given arbitration, or one can see the actors across ISDS as a broader collegium. While the previous studies described above show that the number of dissents in ISDS is low, they may inform the debate in a narrow sense and the results from this article may illuminate the issue on the latter broader collegium. Footnote 61

Multiple scholars, me included, have argued that there are clear indications that a core group of individuals hold significant positions of influence in the ISDS system.Footnote 62 Two connected observations from the data may give indications that there is a system of overall collegiality present. The first is that the use of key terms appears to correlate fairly well between the actors. Although there are variations between them, they all appear to follow the same general trends. Second, the increase in citations is present across all groups of participants. While any direct attribution of this to the benefit of collegial loyalty is a stretch, it nevertheless indicates that all actors find colleagues’ statements and solutions noteworthy, either in the sense that they are useful, or that they are contrary to the actors’ analysis. While not surprising, and completely in line with how other law is practiced, this may however have a flipside. The increased use of citations may affect the independence of the actor. When a given solution to a problem is readily available, and it has been generally accepted, choice fatigue may interact with both collegial loyalty, in a broad sense, and groupthink. This aspect of collegial loyalty may manifest itself in several diverse ways. The first is that if one argues for a different solution than highly respected colleagues, an actor may feel obliged to comprehensively justify why the commonly accepted solution was not chosen. For this issue to occur at all though, the actor must overcome two other limiting mechanisms. As discussed above, groupthink and issue framing may further incite actors to re-use others argumentation. When an issue has been solved by experts in ISDS, often as a result of comprehensive initial debate, it may establish a frame of reference that is challenging for an actor to escape. As actors in ISDS rarely work isolated from each other, this effect is potentially strengthened into a groupthink-like situation where the actor’s own frame of reference creates hurdles for escaping the frame of reference and establishing an original solution.

Beyond considering the generic ISDS actor, a question that arises from the data is the discrepancies between the frequency of change between arbitrators and the other actors. Overall, the parties’ representatives appear to increase their use of new concepts and citations to a larger degree than the panels. A simple explanation for this may be the old adage of “throwing spaghetti against the wall and see what sticks”Footnote 63 or, in other words, that the parties attempt to supply the arbitrators with arguments with the hopes that the panels pick them up and adopt their arguments. To a degree, this is supported by both the observed data and underlying theory. Considering this in light of anchoring and subject framing,Footnote 64 one can speculate that parties are more frequent proposers of legal solutions. If arbitrators find themselves in a position of choice fatigue, they may easily accept one of the parties’ solutions rather than develop their own. Collegial loyalty may further strengthen such tendencies, particularly if there is an imbalance of experience between the panel and the other actors in the case.

Seeing the lack of a formal mandate, in conjunction with the theoretical studies on social, structural, and cognitive factors influencing arbitral decision-making, leads to a final question: Is convergence and cross-pollination a willed strategy employed by the actors to increase their influence, seeking to shape or perhaps repair the system to their preference, or is it an involuntary and unconscious convergence? Answering this with the data currently available is challenging. However, I argue that the results of this study may point towards the latter. The broad and increasing changes over time in concept use and citational frequency, may point in the direction of a slow trickle towards a system that works more practically for its practitioners, and may be more palatable for its critics. Whether it is the individual will or more subtle systematic cognitive mechanisms, it appears clear from the data that the professional actors of ISDS, through their increasing use of citations and new concepts, exercise a role in shaping the evolution of the ISDS system.

F. Concluding Remarks

According to a strict legal-positivistic interpretation of international investment law, actors in ISDS should, prima facie, solely rely on the treaty being litigated when considering a case. Using proxies observed en-masse, through the written output of the various actors, this has empirically illustrated how the actors are indeed breaking with this legal-positivistic premise, and as such, are challenging the isolationist structural outset of ISDS with a more systemic operation. Nonetheless, while the limited scope of the textual analysis and the substantial caveats described above precludes drawing any firm conclusions, I offer some initial thoughts on the questions posed in the introduction.

The proxies applied indicate that there is notable change in the actors’ behavior and citations over time that is not warranted by changes in the treaties they litigate. There are clear indications of change in behavior across all the actors. Much further research is needed both to pinpoint the extent of these changes and their temporal contexts; however, the data does appear to be indicating that informal change, and through it, the professional actors’ exertion of influence on how the ISDS system operates in practice, is indeed occurring.

The shift by tribunals, compared to the other actors, is less apparent, and the tribunals’ use of citations and key terms appears less in flux. On the one hand, to a degree, it appears that tribunals increase their use of citations and key, but are stabilizing faster than the other actors. The internal variations for individual actors on the other hand is quite significant, although this difference may be partly explained by the small amount of data on each individual.

One thing that is apparent from the results, is that regardless of the actor, there is a continuing movement towards greater commonality in the last decades. While this may be influenced by individual actors shaping the system as a strategic tool for their own preferences, the sheer commonality of it indicates that this growth has a systemic mechanism of influence to it.

This empirical understanding shows that the system is perhaps not operating as states designed and intended it to be.Footnote 65 This insight may allow them to perform sufficient reforms and redrafts to allow the system to remain well functioning over time, insulated from the influence of secondary actors, and without the risk of weakening its authority and the legitimacy of its executors. While much further study is required to conclude, it is perhaps not out of line to argue that the professional actors are gradually materializing a “self-constituting society of law.”Footnote 66