A. Prologue: On Context

This essay is a result of the coronavirus pandemic. In November 2019, I decided to ask for a research semester for the fall of 2020, and I explained to the dean and associate dean of research that I would continue my work on gender and legal culture, and Chinese legal culture. My research center had a visiting Chinese PhD student as a guest. At a supervision meeting on January 23, she was extremely upset, because Wuhan—where she had studied—had just been locked down completely before Chinese New Year. I began to realize that my plans for China trips, and consequently for the research semester, would need to be changed. Two weeks earlier, I had participated in a course on Nietzsche at a Danish Folk High School. Then came the lockdown—and for me more time for reading. I read Piketty’s newest book, a new translation of Boccacio, and Thomas Mann’s Der Zauberberg. I began considering switching my research focus to German legal culture, to write an essay—in English—to keep it practicable and to address it to Nordic and international audiences, where knowledge about Germany has diminished in part due to limited linguistic knowledge.

I drew on my—primarily female—contacts with relations to Germany during the last quarter of a century. In September 2020, I managed to undertake a two-week trip to Germany. First, I went to Halle to visit the Max Planck Institute for Social AnthropologyFootnote 1 and stayed at a guesthouse in an old Gründer villa in the northern outskirts.Footnote 2 The staircases were extraordinarily wide and imposing. The whole area had the air of late-nineteenth century enormous economic disparity, which Piketty writes about in his book on Capital and Ideology from 2019.Footnote 3 It was a very interesting and international environment but rather closed down due to corona.

Figure 1. Staircase, Halle MPE.

It was extremely warm for the season, reminding us of the ongoing climate crisis, covered up behind the corona crisis. Many things were not possible, but there was considerably more time for informal communication. Second, I went to Berlin to stay at the guesthouse of the Humboldt University—probably going back to the times of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). I had stayed there in 2006—in the early digital era, before the smart phone. Not much had happened to the guesthouse. However, across the street was a huge, renovated complex of clearly important and ambitious historical architecture. The part of it facing the Spree River had enormous half-rounded windows. There were no signs indicating what company would be seated here, and I saw very few people in the building, entering and/or leaving. But generally using Google Maps, I realized, at some point, that this was the headquarters of Big Tech, Google Berlin. For historical reasons Germany has been skeptical towards digitalization and surveillance—thus the Google anonymity. The semester would start in October. Humboldt University was almost hermetically closed for outsiders. As elsewhere, it had been forced to go digital from the beginning of the pandemic.

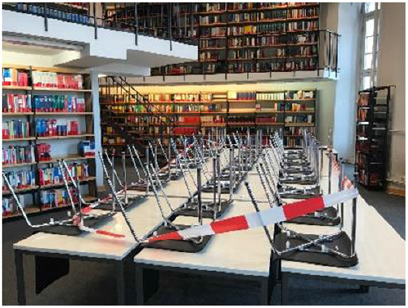

I managed to make some interviews, have more informal conversations, and to visit libraries—the empty Humboldt law library—with difficulties. I bought as many relevant books as I could carry, and got on the network list of the Center for Transdisciplinary Gender Studies at Humboldt University.Footnote 4 This has given me access to information and enabled participation in a huge number of interesting online events. Digital sources have, of course, been crucial during these times.

What has happened to Germany and German legal cultures within half a century? Most writing in Germany and abroad has dealt with the last century, and especially the Post World War Two period. However, in Halle, I had come across Alan Watson’s Sources of Law, Legal Change, Ambiguity,Footnote 5 which more or less deals with the situation in Germany in the last millennium—as did Neil MacGregor’s highly interesting and illustrated book on Germany: Memories of a Nation,Footnote 6 which accompanied an exhibition at the Danish National Museum ending in February 2020. I decided to look a bit further into historical perspectives.

B. On Bias?

Let me start with John Le Carré (1931-2020), the author of Cold War spy fiction. In February 2020, my book club had read and discussed what became John le Carré’s last novel, Agent Running in the Field–for which he received the Olof Palme Prize.Footnote 7 The protagonist, forty-seven-year-old Nat, is approached and later befriended by a young introvert, solitary and somewhat isolated man, Ed, at his badminton club. Ed is the second important figure in the spy novel, which has been described as le Carre´s “Brexit novel”—with a strong element of criticism and reflection on contemporary British politics. Personally, I particularly noticed the description of Ed’s relation to—and even affection for—Germany:

Ed had the German bug in a big way. I suppose I have it myself, if only from the reluctant German lurking in my mother. He’d spent a study year in Tübingen and two years in Berlin working for his media outfit—Germany was the cat’s whiskers. Its citizens were simply the best Europeans ever. No other nation holds a candle to Germans, not when it comes to understanding what European Union is all about … I never asked him, but I think it was Germany’s atonement for its past sins that spoke most forcefully to his secularized Methodist soul: the thought that a great nation that had run amok should repent its crimes to the world. What other country had ever done such a thing? He demanded to know. Had Turkey apologized for slaughtering the Armenians and Kurds? Had America apologized to the Vietnamese people? Had the Brits atoned for colonizing three-quarters of the globe and enslaving numberless of its citizens?Footnote 8

I had grown up in Western Germany since my birth in 1951 and left for university studies in 1970—half a century before embarking on this essay—but I was not a German citizen. My parents had moved there in 1950 to work at the Danish minority schools and stayed until 1989. The small village in Schleswig Holstein close to the Danish border, where we lived from 1954, had housed a small satellite of a concentration camp—Neuengamme—during a brief period at the end of 1944. As children, we knew there had been a camp, but otherwise knew very little. Local people were not willing to talk, even more than thirty years after the end of the war my father realized, when he tried to investigate what had happened. Especially in the twenty-first century, much more information has become digitally available. About 2000 inmates had been forced to work on the “Frisian Wall,” a defense system of the Nazi regime towards a potential British attack from north. They lived in a former work camp designed for 250 people. A large group of men came from a small Dutch village, Putten, and were transported there as a retaliation for offending a higher ranking German military official.Footnote 9 About three hundred men died within a few months having been overworked, starved, and poorly dressed. Due to the political influence of the local German priest, who was one of the first members of the Nazi Party, he was able to bury them indicating their names, and not in mass graves. I learnt in 2020 that in 1932, at the elections to the Reichstag, more than 84.6 percent of the small population of the village voted for the NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei). The area was poor, had little infrastructure, and was in a peripheral position. There were around 1000 smaller concentration—and work camps—all over Germany.Footnote 10 In 1950, a memorial was established at the local church—also due to the bicultural and bilingual history of the area. Growing up witnessing the many men, including in the minority who had served in the German army and were marked on their bodies and souls, was an unconscious experience of German trauma and repression of memory. A father of a schoolmate had been to Russian camps for about five years, many had lost family members, some still hoped for them to return. Consequences of war were visible and sensed.

During much of the Cold War, hostility towards Germans and Germany was considerable in the Western world, especially in the countries which had been occupied. Feelings were ambivalent—and perhaps also puzzled. How could such cruelties happen? The culture was one of silence and concealment. Danish schools in Schleswig-Holstein had to follow regulations by the local Federal state considering structure—starting school at six, going on to Realschule or Gymnasium from ten to eleven years old for between four or seven years, and adhering to context and curriculum adapted to a situation where pupils had to be taught two mother tongues. One of the places where the silence was lifted somewhat was in the literature for German classes in the gymnasium where, for instance, Heinrich Böll and Wolfgang Borchert were part of the curriculum. These authors were dealing with the trauma they had experienced during the Third Reich and World War Two. Literature and arts were probably some of the first fields working with the past and attempting to deal with traumatic experiences. Art was an important way to come to terms with the past.

I moved to Copenhagen in 1970 to study law—combined with sociology. At the time, Denmark was not yet a member of the European Economic Community, and law was a highly national discipline. Literature was in only Danish, and there was no plural linguistic or cultural context. Due to the 1955 Copenhagen–Bonn and Bonn–Copenhagen declarationsFootnote 11 —not an agreement but two identical yet separate documents—students from the Danish Gymnasium, Duborgskolen, in Flensburg, which I had attended, were allowed to undertake university studies in both Germany and Denmark. In 1976–1977 I studied law for a semester at the University of Bremen, which offered probably one of the most interdisciplinary and modern law degrees at the time. Around that time, I had also turned my interests towards Women’s Law, another bias of mine, where Germany had far less to offer. In the summer of 2006, I happened to spend a couple of weeks at the Humboldt University in Berlin. I was a guest teacher and was working on proofreading a book on legal pluralism in practice. I was not aware that my stay would overlap with the World Cup, as I was not particularly interested in football. However, this global event where “the world came as guests to visit friends”—“Die Welt zu Gast bei Freunden”—, was when I first realized something like the changing sentiment of Germans and toward Germans—as expressed by Ed in le Carré’s novel. About sixty years after the end of Word War Two, Germans seemed to me happier, freer, more friendly, and more considerate than I remembered them from my childhood and youth. The first decade of the twenty-first century was also the century of “unified Germany”—with all its challenges and difficulties. It represented hopes of a more inclusive and democratic EU, and a still hopeful attitude towards an emerging new World Order.

C. Legal Pluralism and German Mirrors: Der Sachsenspiegel, Fürstenspiegel and Der Spiegel

I have been interested in legal pluralism since working with issues of women and law in my doctoral dissertation in the 1980s. Eugen Ehrlich’s work on “living law,” as described in his Grundlegung der Soziologie des Rechts Footnote 12 , was an important source and inspiration. Ehrlich (1862–1922), now much more well-known than in the 1980s, came from multi-lingual, multi-religious, and multi-cultural Bukovina, and was educated and taught in Vienna, the capital of the multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic Austro-Hungarian Empire soon to collapse after World War One.

Contemporary Germany of the twenty-first century, with its federal structure, goes back to the Middle Ages. The establishment of the German Kaiserreich brought together a considerable number of smaller and bigger monarchies, duchies, city-states, and dioceses. Maps of Germany before 1871 resemble patchworks, where both law and moneymaking took place in a complicated context, as MacGregor, supra explains. German tradition reminds us that law is not necessarily a textual, top-down phenomenon produced by “higher” authorities. This is particularly clear from a historical perspective.

Figure 2. COVID-19 closed Law Library, Humboldt University Berlin, Sept. 2020.

Der Sachsenspiegel—The Mirror of Saxony—is the most famous German law book from the Middle Ages—between 1215 and 1235—from a period, which was characterized by two dominant conflicts between the Staufern and Welfen, and by the ambiguous relation between Emperor and Pope.Footnote 13 Heiner Lück, professor at the Martin-Luther University in Halle, writes that medieval legal culture was predominantly oral, and that this situation lasted for several centuries. Law was highly heterogeneous. The mass of norms consisted of unwritten customary law, and what was proper law was in practice demonstrated for contemporary people insituations of conflict. Norms differed considerably territorially, locally, and personally. They differed according to estates, and thus in relation to different social groups—clerical and secular. Cities were legally specific areas, where city laws and privileges were applicable—especially in relation to trade and crafts. The law of the countryside (Landrecht) differed from city laws.

The Sachsenspiegel was a privately organized recording of customary law, which no authority ever declared valid law. It concerned Landrecht of the countryside and Lehnsrecht—feudal rights. The Sachsenspiegel was translated from Latin into German and later illustrated to increase its influence for a less literate audience and make it more applicable. It was imitated—or as Watson describes it, transplanted—to many different communities in North-Eastern Europe.Footnote 14 The cities of Magdeburg—now in Sachsen-Anhalt and earlier also a religious center—and Lübeck were very important trading cities at the time. In the Middle Ages, it was common to make use of laws from an older “mother” city—such as Magdeburg or Lübeck—to design the legal “constitution” of younger “daughter” cities. In addition, the city laws of “mother cities” were not binding but rather tools for information and inspiration for the “daughter cities,” which could adjust, revise, and reject certain regulations. The role of intellectual, economic, and religious centers in the world at large, in Europe, and in the German speaking areas in Europe was to contribute to the development and spreading of knowledge. Unwritten and written norms and laws were transplanted, imitated, loaned, and used selectively. Something that produced considerable flexibility and limited uniformity. The existence of many different and rather small states combined with a heritage of normative and territorial pluralism and diversity is still palpable in the present Federal Republic of Germany.

Another type of “mirrors,” which have been important in German and European history also date back to the Middle Ages are the so-called “Speculum Regis,” the “Fürstenspiegel,” “Mirrors of Dutches” or manuals of statecraft. These are “mirrors” held in front of the royal, ruling addressee, often a Prince or Duke, in order to guide him in governing and educating a—future—ruler. Such texts reflect political ethics, pedagogy, criticism, or praise of such a ruler. They reflect the ideal of the good ruler at the time. Machiavelli’s The Prince is perhaps the most well-known example of this literary genre today. Such mirrors were highly influential in the fragmented German speaking area. In 1947, the still very influential news and cultural magazine in—West—Germany, Der Spiegel, was established highly inspired by the American ideal Time. I expect the name relates to the normative, political, and ethical importance of the figure of also the symbolic ethical mirror in German history.

D. Federal and ideological pluralism in law

The present Federal Republic of Germany is made up of sixteen units all together, of which thirteen are Länder,Footnote 15 while three—Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen—are city-states. The Bundesrepublik (re)established itself after what Kowalczuk—2019—calls the 1989 “unimagined revolution,” which was followed by what he calls the “takeover” of GDR.Footnote 16 In this process five new Länder were created, namely the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, Sachsen, Sachsen-Anhalt, and Thüringen.

The principle of federalism was neither new nor unknown to post-war Western Germany, where the Allied Forces, and especially the US had an important influence on the processes of the (re)constitution of this German state. The German Grundgesetz—the West German Basic Law, not Verfassung—came into power in 1949. It was prepared by a Parliamentarian Council consisting overwhelmingly of representatives from the then-existing German Länder. The period was characterized by a prevailing skepticism towards the influence of “the masses” and the institution of the referendum after the failed Weimar Republic. Hedwig Richter writes that federalism may also be interpreted as a restriction on pure popular sovereignty.Footnote 17 The weak role of the Federal President and the strong role of the Kanzler, was a reflection of this skepticism towards a representation of the people, towards parliaments and towards parties. The Grundgesetz was established with a strong focus on values—“Die Würde des Menschen ist unantastbar”—as a reaction to Nazism and fascism, and a strong focus on the executive and judicial power.Footnote 18

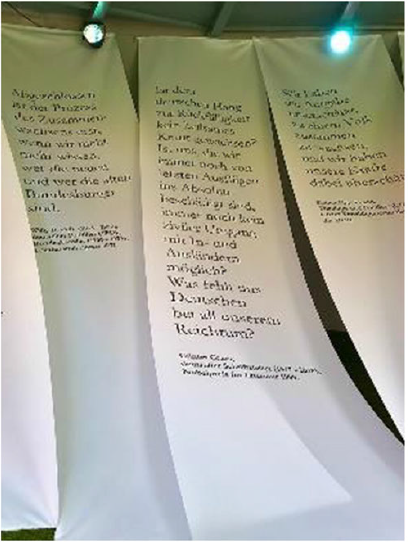

Figure 3. Exhibition on German Unification, Halle Sept. 2020.

In his article, Revolutionary Constitutional Lawmaking in Germany-Rediscovering the German 1989 Revolution,Footnote 19 Stephan Jaggi highlights that the 1989 Revolution did not lead to an unconditional adoption of West German constitutional law in the new East German states, even if conservative western German elites

“did everything to prevent any influence of eastern thought of the western system. They wanted the western system to be perceived as the winner of the historical battle between capitalism and communism, and they were convinced that the winners did not need the losers to make reform proposals.”Footnote 20

According to Jaggi, all new Länder constitutions contain provisions on individual empowerment and environmental protection, and this was also the case for the heavily revised constitution for the reunified city state of Berlin, which, to him, is “a paradigm example of a state constitution transferring revolutionary achievements to the West German constitutional order.”Footnote 21 The “individual empowerment” is a concept according to which the state is “constitutionally responsible for shaping a social environment in which individual constitutional rights can become a social reality for everyone.”Footnote 22 The citizen’s movements were strongly influential in the framing of the principle of individual empowerment, which according to Jaggi, did not least have a focus on women’s rights—real equality and not just formal legal equality – including right to “self-determined pregnancy.”Footnote 23

The contested federal and ideological pluralism is palpable in Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk’s book from 2019Footnote 24 on occasion of the thirty-year anniversary of the 1989 revolution and the 1990 “unification” of West and East Germany. Kowalczuk—as Richter—sees this development as part of an international development of globalization and a neoliberal market economy.Footnote 25 There is no doubt that there are still considerable economic, political, and mental differences. Every second East German still feels as a second class citizen. Present elites in the new Länder only as an exception come from the East. At courts in East Germany, only ten percent of judges come from East Germany. Pegida and AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) are “synonyms for a racist, antidemocratic, nationalist, authoritarian, and anti-freedom attitude, which is more widespread than election polls or election analysis alone may capture.”Footnote 26 Kowalczuk describes how his understanding and evaluation of the “take over process” has gradually changed after the financial and banking crisis in 2007, where enormous amounts of money were used to secure capitalism and banks.Footnote 27 His original enthusiasm about the fall of the German Democratic Republic has become more aloof and nuanced. In her book from 2006 Gerechtigkeit in Lüritz: Eine ostdeutsche Rechtsgeschichte, Inga Markovits,Footnote 28 a German–American professor, describes in detail how the judiciary in the city of Wismar gradually lost belief and trust in the meaningfulness of both the general political system of the GDR, during the 1980s, and in the judiciary itself. She describes a worn-out system, where both the population at large as well as the—predominantly female—judges, lost enthusiasm, and almost waited for a collapse.Footnote 29

E. On Language(s), Gender, and Plural Order

In Germany, Memories of a Nation, British cultural art historian, Neil MacGregor writes about the importance of “one language for all Germans,” in spite of the fact that there are many German dialects.Footnote 30 This is due especially to the highly important role of the Reformation for not only religious, but also linguistic, political, and legal culture in the German speaking areas. Martin Luther’s translation of the Latin version of the New Testament after his protest in 1517 against the moral and economic corruption of the Catholic Church has had a strong influence until present day Germany.Footnote 31 It introduced a German written language, which would come to unify its users in spite of territorial fragmentation and an emerging religious division of the European area—especially after the conclusion of the Treaty of in 1648, where an order was established very much along religious lines. The present German Federal Republic is a conglomerate of Länder of mainly Protestant heritage in the North, mainly atheist heritage in the new Länder of the former GDR, and mainly Catholic heritage in the middle and South of Germany. This heritage, mixed composition, and challenge has made Germans used to a political, religious, cultural and normative diversity.

German is a gendered language to a much greater degree than are Nordic or Anglophone languages. Since the 1980s, this has given rise to an increasing discussion and regulation regarding what in German is called “geschlechtergerechte Sprache”—gender just language—,Footnote 32 sometimes also called “gendergerechte Sprache.” As of October 2020, the German Wikipedia has a sixty-page article under this heading. It concerns a linguistic use, which aims at equal treatment of men and women—and all other genders in relation to personal reference/naming in both written and spoken language. For instance, “citizen” would be Bürger or Bürgerin in German, where nouns are either neutral, male or female, and adjectives are inflected accordingly. Many languages use what is called “generic masculine” to indicate both or all genders, in German thus Bürger was used for everybody regardless of gender. Feminist linguists, increasingly also politicians and other groups, have challenged this during the last forty years. This has given rise to linguistic developments, practices, and regulations, where the personal reference for Bürger could be written as “Bürger und Bürgerinnen”—in German “Beidnennung”—naming both—or in a shorter contracted form BürgerInnen—Binnen-I – an inbetween-I—, and another contracted form Bürger*innen—Gender-star. From the point of legal culture, it is interesting to note that in the “German speaking area” government agencies have, since 1980, produced several administrative regulations and decrees in this field in both the Federal Republic of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.Footnote 33 These regulations concern the professional legal language. In 1980, the German Civil Code—Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch BGB—introduced a ban on only announcing positions for either male or female applicants. Starting from 1984, the different Länder and city states introduced a Circular on linguistic equal treatment of men and women in official forms, starting with Hessen, Bremen, Saarland, Berlin and Baden Württemberg and continuing to include all Länder in 2020 apart from two of the new ones—Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Sachsen-Anhalt. The abovementioned Wikipedia article shows that this development has started from more progressive federal and city states and from there moved on to the rest of the German speaking area. This gender example thus underlines the important role of linguistic proximity, imitation, and cultural change.

Figure 4. Google Berlin at night, Sept. 2020.

F. Gender and Political and Legal Cultures

In the 1950s, Germany was governed by old men. Konrad Adenauer (1876–1967), former mayor of Köln, seemingly lasted forever as Kanzler from 1949 to 1963. Richter claims that an old gender order provides stability in times of transition.Footnote 34 The atmosphere of a patriarchal, post-totalitarian, and post-war state lasted for more than two decades. There were few women in politics or law anywhere in the world at the time.

German women had achieved the vote in 1919 after the establishment of the Weimar Republic, and as part of a global and international movement at the end of the ninetenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. Marion Röwekamp writes in her article on Women, Equal Rights, and the Legal Profession in Germany, 1885-1933 that, for historical reasons, the fight for women to get access to the legal profession was even harder and more strongly resisted in Germany than the fight for female voting rights.Footnote 35 This was especially due to the special German legal education system, which ensured that all lawyers “were qualified and in turn, guaranteed access to all legal professions, including civil service and the judiciary.”Footnote 36 It took World War One, the fall of the German Empire, and the establishment of the Weimar Republic to diminish this resistance. The 1922 legislation, which allowed women to become judges, met serious resistance in the legal profession among judges and advocates. Women were not considered suited for “objective” judicial decisions due to their biological constitution commented then female Minister of Justice, Brigitte Zypries, at a conference in 2004 in Berlin, where she spoke about the role of Gustav Radbruch as a legal politician. Radbruch was the Social Democratic Minister of Justice, who introduced this legislation. Under Hitler, women were once again excluded from the judiciary and legal world. The first female minister in a German post-war government was appointed in 1961 and, until the 1980s, female members of government were the absolute exception.Footnote 37 After the 1968 worldwide youth and political rebellions, things started to change gradually. Richter writes that GDR “seemed to be ahead of” the—West German—Federal Republic in terms of female emancipation, due to the fact that women worked more independently because of the demand for labor.Footnote 38 This may also have been a driving force for the gradual emancipation of Nordic women. Additionally, the popularity of re-united Berlin amongst many Nordic citizens may also have been due to a familiar city culture in terms of gender order.

While many lawyers and judges in the GDR had been women, it was considerably longer in West Germany before women gained a foothold. Nordic women’s law activists and theorists looked across the North Atlantic to the US and Canada as well as to Australia and New Zealand for inspiration, and to some extent still do. In her 2020 article on Gender in Socio-Legal teaching and Research in Germany, Ulrike Schultz has a striking table on the “Proportion of women in the legal professions in the period from 1960 to 2019.”Footnote 39 Because the figures are almost non-existent in 1960, I will mention the figures for 1970 and 2019—a period of almost half a century. In this period, the number of female advocates grew from 4.5 percent of all to 35.1 percent; female judges’ participation grew considerably from 6 to 45.7 percent; public prosecutors from 5 to 48.6 percent; female law students from 17 to 53.7 percent, and female law professors from only 0.1 to 16.7 percent—the lowest absolute percentage of all.Footnote 40 Schultz writes that the increase in numbers after 1989 is due to reunification, while the data before only concerns West Germany.Footnote 41 The table underlines the very weak representation of female professors in education. German professional legal culture has become much more gender equal, but universities are clearly lacking in gender modernization. This is an aspect characteristic of the continental European civil law culture, where professors have held higher status than judges, contrary to the Anglophone legal culture, where the status is reversed. This has a general impact on political and democratic legal culture, where participants and parliamentarians have often been members of the legal profession. There have been few female political leaders in Germany until the twenty-first century, and the most notorious have not been from the legal field.

Angela Merkel, the prominent East German physicist and daughter of a Protestant priest, entered German politics after the 1989 revolution as member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). At that time, it was still difficult to imagine a female Kanzlerin, and nobody would have predicted that she would hold this office longer than both Adenauer and Bismarck, although not longer than Helmut Kohl, who promoted her. In this respect especially, Germany has changed considerably. A young woman, born in the GDR in 1986, who I interviewed for this article, claimed that Angela Merkel was not really considered a woman. She was not identified by her gender, but by her position as head of state. I have wondered if the otherwise perhaps rather invisible influence of East German politics and norms have their strongest impact in the new German Federal Republic via the personality and leadership style of an originally East German woman. Merkel has lived a life characterized by value pluralism: socialist ideas, natural science, protestant Christian opposition, a reconstructed Republic characterized by a heritage of state socialism, and a social market economy order coming to terms with a heritage of totalitarian National Socialism. The “unification/take-over” of 1990 has forced contemporary Germany to consider values, relations, and orientations in ways that are different and perhaps challenging to other neo-liberal legal cultures and competitive states. In an article from 2009, Barbara Stiegler, then at the Social Democratic Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, wrote that one cannot expect an explicit relation between gender and political action.Footnote 42 There are traditional and alternative self-expectations and perspectives on gender.Footnote 43 However, a biological gender may give rise to gendered action, given that gendered relations in a society are not egalitarian, and that personal experiences are not understood as individual problems but rather as political expressions of dominant gender structures. Before unification, a Christian conservative gender ideal dominated in West Germany, while an ideal of partnership dominated in East Germany, where the woman was professionally qualified, and expected to participate in both the labor market and society. A man was not considered as a breadwinner even if the gendered division of labor in the family remained traditional. While mothers in West Germany had a labor market participation of below forty percent, supported through a gendered taxation system and lack of infrastructure for child care, labor market participation of East German women was around eighty percent. At the time of unification, fifteen percent of parliamentarians in the West were female, against thirty percent in the East—where Parliament was also less influential.Footnote 44 The West was concerned about a gender just language, which was not the case in the East.Footnote 45 In the Catholic/Protestant West, women had long been fighting for abortion, while the East had had a right to abortion since 1972 but had no discussion about domestic violence. Thus, two rather different gender and political traditions and cultures were brought together after 1990. Women in the East lost the right to abortion, their unemployment rate grew considerably, and their part of economic and political managerial positions stagnated.Footnote 46

According to Stiegler, the Kanzlerin—the female noun—as an East German physicist without children, thus had few—personal—experiences of gender discrimination, both biographically and in her rapid political career.Footnote 47 She has not produced any publicly visible gender political activities, and seemingly does not show any understanding for societal and structural conditions, which produce and support gender inequality. Nonetheless, the infrastructure for childcare below three years of age was considerably improved during her first period as head of state. Her impact was primarily symbolic, and her relation to her own gender, was one of “de-gendering,” which did not acknowledge nor address the patriarchal political culture. In relation to the media, the view has been that “[e]ine Frau ist entweder mächtig, dann ist sie keine Frau, und wenn sie eine Frau ist, dann darf sie nicht mächtig sein”—“A woman is either powerful, and then she is not a woman, and if she is a woman, she is not allowed to be powerful.”Footnote 48 However, during her long period as Kanzlerin, Angela Merkel has contributed to a change in particularly the German political and leadership culture, which has an effect on the legal culture, and which, with the recent German female chair of the European Commission, may contribute to further German and European change, even if the next Chancellor will be male. The fact that the Green Party selected a female and young candidate for Kanzlerin for the 2021 elections also bears witness to a changed political German culture.

Figure 5. Ursula von der Leyen speaking to European Parliament, Sept. 2020.

G. Towards Democratic Cultures

One effect is clearly observable in Hedwig Richter’s 2020 book on Demokratie. Eine deutsche Affäre. Vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart Footnote 49 Her intention is to study the development of democracy in relation to four theses, according to which history of democracy is often: 1) a project of elites; 2) a story of limitations of democracy; 3) a story about the body, its maltreatment, care, malnourishment and dignity; 4) and an international history particularly of the North Atlantic area. These foci include strong perspectives on both colonialism, racism, and gender discrimination.

In the first section on elites and people, she discusses the abolition of torture in 1755 by Prussia.Footnote 50 Torture became gradually scandalized and unacceptable, and arguments in favor of a more humane criminal law spread. She contemplates that compassion (Mitleid) was an important feeling considering the dignity of fellow human beings, as was empathy concerning their pain, and outrage towards abuse and a miserable life—a respect for the body. Compassion was a child of the Enlightenment and developed into a powerful idea, which nourished the idea of equality.Footnote 51 Richter claims that the new ideas of democracy would be dependent on new feelings and new manners regarding the body, as power relations are inscribed in the body.Footnote 52 Those, who may be beaten, who do not own and govern their own body, cannot be considered political subjects, who have come of age. It was completely inconceivable for most humans that women, serfs, or dispossessed farmers could be understood as equal and responsible citizens. Compassion relating to the body became “the foundation of a new sense of justice: the sense of a right to have rights.”Footnote 53 She portrays a more peaceful German tradition of the eighteenth century than that of the French Revolution. The philosopher Herder, in his argumentation, links peace and femininity and sees women as a conciliatory and peacemaking element. According to Richter, the work on a new body and emotional regime was linked to a criticism of masculinity in the beginning of modernity.Footnote 54 A proper cult of the weak developed. This had an impact on the understanding of equality amongst gender. The household had, for centuries, been a hierarchical area, where women were required to obey. Men had a right to domestic violence, and women had a relative lack of rights in relation to both property and body everywhere in Europe before the nineteenth century.Footnote 55 Inequality had now become something which needed to be legitimized. In the nineteenth century, compassion was also furthered through the arts, and particularly through literature at a time when a growing part of the population became literate. In Germany, the idea of a Kulturnation—a cultured nation—spread. Due to the defeat of Prussia in the Napoleonic Wars in 1807, Prussia was especially keen on modernizing the state into a consistent, efficient, territorially homogenous area of power with the monopoly of a legitimate state authority. This required religious tolerance.Footnote 56 During the eighteenth century, most European states had introduced comprehensive reforms of government, administration, law, and education. Austria had enacted a Civil Code in 1786 and Prussia a General State Law for the Prussian States of 1794Footnote 57 before the enactment of the famous French Code Civil—or sometimes Code Napoleon—from 1804.

The gradual change from feudal monarchies based on mainly agriculture to modern constitutional monarchies, and later republics in increasingly industrialized societies, took place during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Europe. This development was related to tensions between the countryside and the cities. A new liberal legal order interlinked with a new emotional order. Elections were gradually introduced. “Democracy is also always an educational project—a deeply civic project of self-discipline,” writes Richter.Footnote 58 The 1840s were years of hunger and poverty in Europe and Germany, where the cotton weavers revolted in the summer of 1844, marking a new sense of justice.Footnote 59 All of Europe experienced revolts bordering on revolutions in the year of 1848—when Marx and Engels published the Communist Manifesto. Art, literature, and especially the new market for newspapers contributed to a change of values, and to scandalizations of poverty and hunger. The traditional gender order served as an anchor in these turbulent times —women did not receive a voice or vote until much later.Footnote 60

In March 1849, the Parliament of the Paul’s Church in Frankfurt met to decide on a constitution. More than fifty percent of the Parliamentarians were civil servants and almost every second was trained in law. At the time, it was self-evident that women could not join. Neither Prussia nor Austria joined, and the Parliament could not prevail.Footnote 61 About two decades later—after wars against Denmark in 1864–66 and particularly against France in 1871—the German states were united in the German Empire with Prussia. The same year general voting rights were introduced for men, while corporal punishment was outlawed.Footnote 62 The years at the beginning of the twentieth century were years of reform and change, but also years of nationalism, militarism, anti-Semitism, racism, and genocidal colonialism—nationally and internationally.Footnote 63 Moreover, the twentieth century saw two bloody world wars, the collapse of several empires, Nazism, fascism, and genocide. As this is a very well-known story, I will focus less on this here.

From my perspective, Richter’s contribution to a history of German democracy lies particularly in her emphasis on a longer time perspective transcending the twentieth century, and not least on the importance of the body. In terms of legal culture, the period after World War One brought the fragile and short-lived Weimar Republic in Germany, which built on parts of the constitution from Paul’s Church in Frankfurt, and as already mentioned, expanded voting rights to women. After 1945, and twelve years of Hitler’s dictatorship, Germany would become divided and oriented towards respectively socialist and democratic ideals in the two parts during the period of the Cold War—which was also a period of reconstruction. In West Germany, a gradual return to a democratic legal culture took place. East Germany turned towards an understanding of law inspired by Soviet legal theory and practice, where law was considered more of an instrument of order and regulation.

Figure 6. Berlin Government District, Sept. 2020.

H. Nordic and Other Perspectives

In 1984, Finnish legal historian, Lars Björne, published a book entitled Deutsche Rechtssysteme im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert partly covering the same period as Hedwig Richter does in her book on democracy.Footnote 64 He writes in the beginning of the book that it was originally considered to become an introduction about the reception of German legal systematics in Scandinavian legal science. During his work, it turned out to become more meaningful to present the development of German legal science independent of this history of Nordic reception. When I received the book from the Royal Library, I was surprised to find that it basically consisted of a presentation of forty-eight individual authors, who had historically been dealing with legal systematics. Not surprisingly, all of these authors were male.Footnote 65 To me, the book underlined the changes, which have after all taken place in legal academia in and beyond the Nordic countries during the last fifty years. The changing gender composition of the profession, and especially of the student body, has changed academic perspectives on history, science, and culture. Most likely Björne’s presentation mirrors the territorially fragmented political situation in the German speaking area for most of the two centuries covered by the book. Individual academics—as well as important and high status educational institutions and universities—probably mattered more than “national identity” in one or another smaller German state. Development of legal systems also mattered more for the process of establishing a common thinking and ideas across borders. The most famous name outside of Germany is probably von Savigny. Friedrich Carl von SavignyFootnote 66 was born a decade before the French Revolution, and died a decade before the establishment of the German Empire. He became famous amongst others for his system of private law, inspired by Roman law. He lived in a period characterized by military and ideological upheavals, which were mainly caused by the French Revolution and the Prussian defeat by France in the Napoleonic Wars at the battle of Jena in 1806, as well as by the subsequent growing importance of Prussia. The Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV established a ministry of legislation for von Savigny, where he served as a minister in the period from 1842–1848 ending with the year where a general European revolution spread like wildfire.

The politically fragmented character of the German-speaking area may be an important background for the focus on the role of academia, the legal profession—especially the judges—and the concern with system building and methodology, which seems to characterize German legal culture even into the twenty-first century. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are the centuries of beginning secularization—Nietzsche declared that God is dead in 1882 in Fröhliche Wissenschaft or The Gay Science. Transitions to democracy and industrial societies and to German states unified by way of treaties and wars were taking place. After the establishment of the German Empire from 1871, a “culture of codification” took off particularly with the preparation of the German Civil Code—Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, BGB.

This was a time of military expansion and unification, of class conflict and colonialism, and of a gradual expansion of capitalist democracy. Probably all of these developments contributed to the demand for, and possibility of, producing a common civil code regarding regulation of private law relations. The BGB entered into force in 1900, and parts of it have survived a number of very different political regimes. These are the German Empire,1900–1914, the Weimar Republic (1918–1933) National Socialism (1933–1945), the German Democratic Republic (1949–1990), the Federal Republic of Germany (1949–1990) and presently the united Federal German Republic (1990–present).

In his 2016 article, On The German History of Method in Civil Law in Five Systems, Hans-Peter Haferkamp writes that Germany is the country of legal methodology, and that “[n]o other country saw such an intense academic discourse on the question of what jurists are able, allowed, and supposed to do when interpreting and applying the law.”Footnote 67 He attributes that to the history of the BGB, where preliminary work on the preparation had already begun in 1874, and writes about the distrust of German academia and jurists, who had no confidence in the legislature, the judiciary, or the BGB—which was criticized for being inflexible, outdated, and politically unsound from the very beginning. During the debates about codification, around 1900, the era of German methodology started.Footnote 68 From reading Haferkamp’s article, it is my impression that the difference in interests, values, and attitudes of professions, classes, and social groups were considerable during especially the beginning of the twentieth century. Considering Röwekamp’s arguments above about the strong power of the German legal profession, and its vehement resistance to accepting new—female— members, the legal profession seems to have been very reluctant to accept any interference in its business. As Haferkamp says: “The Weimar era witnessed theories adopted across political divides, in socialist as well as in conservative circles, which dismissed the concept of private law as being a pre-state sphere of freedom and conceived private autonomy as allocated by the state and ancillary to the interests of the community.”Footnote 69 This era in Europe often underlined the importance and legitimacy of positive law and legislation produced by the majority of political representatives elected by an—expanded—electorate of “citizen”—a political and legal culture, which increased the political importance of industrial workers against owners of private property and business.

According to Haferkamp, the Akademie für deutsches Recht established in 1933, after the takeover of Hitler and National Socialism, continued to discuss the issue of a new National Socialist private law, where “the idea of duty and community [would] destroy the legal form”.Footnote 70 Several of the participants of the Academy and of this discussion continued their careers after World War Two. In 2018, Norwegian professor of law Hans Petter Graver published an article titled, Why Adolf Hitler Spared the Judges: Judicial Opposition Against the Nazi State.Footnote 71 In that article, he reflected upon the loyalty of a judiciary, who willingly transformed liberal German law into an instrument of oppression, discrimination, and genocide, without the Nazi regime needing to interfere substantially with the operation of the courts, and without it applying disciplinary measures on the judges.Footnote 72 Graver writes that Hitler hated judges, but nonetheless did not want the party to interfere with the functioning of the judiciary: “The legacy of Western legal tradition seems to have tempered even Adolf Hitler.”Footnote 73 So even if—or because?—few judges displayed opposition against the regime, the profession—judiciary—seemed to show both professional loyalty towards each other as well as to the regime in place. The culture of—to some extent unquestioning—professional solidarity, protection by old networks, and loyalty towards both profession, networks and state was very strong and continued after World War Two and during the period of denazification. Graver quotes from an article from 1948 by Karl Loewenstein, writing on the Reconstruction of the Administration of Justice in American-Occupied Germany.Footnote 74 Loewenstein writes that

Here enters a socio-psychological element which AMG (American Military Government) was unable to neutralize—the class solidarity of the judiciary, which subconsciously or consciously, began to balance and outweigh the desire for political cleanliness. In fact, under the impact of occupation, a certain national solidarity has emerged—not merely in the civil service but among all classes—which tries to save as many colleagues as possible from the clutches of the denazification beast.Footnote 75

Graver considers that the influence of the Western legal tradition characterized by an autonomous legal order going back to the Middle Ages may be an explanation of the—uneasy—power balance between regime and judiciary during the Nazi regime.Footnote 76 Even the Nazi regime did not manage to wipe out this tradition and culture in its twentieth century incarnation.

I. A Constitutional Culture of Human Dignity? “Die Würde des Menschen ist (un)antastbar”

Due to the atrocities performed during the Third Reich, the American led “reconstruction of the administration of justice” in what became the—Western—Federal Republic of Germany, consisted of the denazification process through, amongst others, the Nuremberg Trials (1945–1946), the Grundgesetz (Basic Law) from 1949 and the introduction of a new institution, the Bundesverfassungsgericht (Constitutional Court). The Grundgesetz states in Article 1 that “Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority.”Footnote 77 This can perhaps be said to be a credo of the reestablished German—capitalist—federal state. Article 2 deals with Personal Freedoms.Footnote 78 A very important judgment from 1958 by the Constitutional Court, the Lüth Judgment, concerns Article 3.2. of the Grundgesetz on Equality before the law, “Men and women shall have equal rights. The state shall promote the actual implementation of equal rights for women and men and take steps to eliminate disadvantages that now exist.”Footnote 79 According to Haferkamp, this judgment stood at the threshold of a new chapter—that of the constitutionalization of private law. The debates in the 1950s as to whether this article required the obligation of equal treatment of men and women in the field of employment law lay behind this judgment:Footnote 80 “Via the general clauses, the Court now began to assert from the fundamental rights in the constitution a “‘behavioural canon for society as a whole” as a means of protection from the state.”Footnote 81 This marked the beginning of a “depoliticization of thought on civil law.”Footnote 82

Susanne Baer, professor of Law and Gender Studies at the Humboldt University in Berlin, has, since 2011, been a member of the Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe appointed by the Green Party—which uses gender quotas for its parliamentarians—for the designated twelve year period according to the rules. In January 2021 nine of the sixteen judges were female. Baer writes in her 2009 article, Dignity, Liberty, Equality: A Fundamental Rights Triangle of Constitution, that the three values mentioned in the Grundgesetz, should not be considered as structured as the ends of a scale or the top and sides of a pyramid, or as a hierarchy prioritizing dignity over freedom and equality. She argues that the triangle “is an adequate concept to capture what dignity, liberty, and equality stand for, because it prevents us from overstating any one of these rights in isolation.”Footnote 83 Where issues of dignity were of utmost importance at the time of the installation of the Grundgesetz, Baer claimed in 2009 that equality issues are returning to the forefront. Race is in some sense thought of as class, while gender may be related to age: “Equality politics and equality law move from a focus on identities and assumed or attributed personal characteristics toward a recognition of systemic inequalities, like precarization, a new concept of a classic—that is class.”Footnote 84 While the Nazi Regime rejected human dignity, the social liberal state emphasized dignity as well as equality, and the market state of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries focused strongly on liberty. During the corona period, restrictions in favor of health and security have emerged almost everywhere.

Figure 7. Constitutional Square, Karlsruhe, Art by Jochen Gerz 2019.

The establishment of the Constitutional Court and the concomitant focus and emphasis on case law has meant a certain move from the dominant legal civil law culture focusing on statutory law and legislation in German legal culture. Later, in a 2017 special issue article of the German Law Journal on Pluralities—Speaking Law: Towards a Nuanced Analysis of Cases—Susanne Baer discusses how a “headscarf case” may be used to illustrate a plurality of laws, and how interdisciplinary legal studies become inherently critical to the protection of fundamental rights.Footnote 85 In the 1950s, debates focused on an obligation of employers to secure equal pay in the labor market. In the beginning of the twenty-first century, it has shifted to a claim and concern about accommodation of female members of minority religions, and whether this requires an obligation of employers to accept the freedom of women to wear veils while working as schoolteachers in German schools. In January 2015, the German Federal Constitutional Court decided that a general prohibition on public school teachers from wearing a headscarf or a veil was a violation of the Basic Law’s fundamental rights, making a plea for a greater religious tolerance.Footnote 86 The complainants were women, as well as members of a religious minority, and the presence of a Muslim woman in court outside of legal conflicts surrounding marital and family issues is anything but paradigmatic, Baer underlines, continuing that “what we see when two Muslim women teachers gain access to the court is a disruption of our horizon of expectation.”Footnote 87 Thus the Court-culture also reflects the changing culture and composition of the present day Federal Republic of Germany. This legal culture has—to some extent—to include actors and issues beyond traditional, national, religious, and gendered confines, and is thus forced to transform and accommodate itself to those demands and conditions. Neither legal cultures nor traditions are static and stable, and German legal culture may be a particularly strong example of this.

It is perhaps also an example of a development, which is not unidirectional. The defense lawyer, author, and storyteller, Ferdinand von Schirach, wrote a series of essays in 2016 entitled Die Würde ist antastbar or Dignity is violable.Footnote 88 The title of the first essay is the title of the book, but with the subtitle “Why terrorism decides over democracy,” which underlines the challenges to the legal culture from the violence and terrorism of this century.Footnote 89 The fourth essay “Du bist, wer du bist” Footnote 90 with the subtitle Why I Cannot Give Any Answers to Questions About My Grandfather, is in a way typical of German culture in general. It addresses the questions the author regularly receives about his grandfather, who was the head of the youth organization, Hitlerjugend. The now adult grandchild reflects on the heritage of his Nazi grandfather, his crimes and relations between historical explanations, and personal relations. This is part of the German Vergangenheitsbewältigung—the process of coming to terms with the past—which has, since World War Two, become a significant part of German history and culture, including to some extent also—but perhaps less so—legal culture.

J. A Culture of Silence and Coming to Terms with the Past

Vergangenheitsbewältigung—“overcoming the past”—has become a term, which has had a very important and specific impact and influence on German society since the end of World War Two until today. It is not always translated, but as a German word—it is related to the “atonement”—repentance of sins—indicated in the early quote by John Le Carré. The literature in the field has grown immensely, and my selection of perspectives and titles is both somewhat personally biased and, furthermore, mainly based on sources which have been digitally accessible due to restrictions imposed by the Coronavirus at the time of writing.Footnote 91 The process started immediately after the end of World War Two with the Nurnberg Processes (1945–1949). The de-nazification procedures in what became the West German Republic were led by especially the American and other Allied forces. The de-nazification of the Judiciary in general was quite limited and slow, and was probably not something that many outside the profession and legal field took notice of. Harald Jähner, honorary professor of cultural journalism at the Berlin University of the Arts, writes in his highly illustrated book on Wolfszeit. Ein Jahrzehnt in Bildern 1945–55, that the million crimes committed by the state and its population were repressed by the hardship of chaos in the years immediately after the war and by the own sacrifices by Germans.Footnote 92 A huge number of cities in Europe, but not least in Germany, were bombed and devastated during the mutual terror bombardments of first German air forces and, in the final phases of the war, by Allied forces. To a very large degree, Germans had fled their homes in the Eastern parts of the country. Many lived in ruins or in the shattered cities. Gradually, they became confronted with the atrocities of the genocidal policies of the Nazi-regime. They were displaced, traumatized, shocked, and. undoubtedly to some extent, demoralized. Many men were dead, or physically and mentally handicapped.

The first decade after the war encompassed years of repression of memories and the reconstruction of cities, living conditions, and societies. According to Jähner, forty million out of seventy-five million Germans did not live where they belonged or wanted to go during the summer of 1945. The uprooting of what came to be called “displaced persons” was enormous.Footnote 93 People lived in deserted cityscapes—and most of their time, energy, and little money went into creating order out of chaos—while forgetting or rejecting the past, and making sense of the present. “People stole meaning, as they stole potatoes.”Footnote 94 It was a decade of mixed and ambivalent feelings, where traditional norms and values in all fields, from marriage, to intimate relations, work ethics and legality had collapsed. However, the journalist Margret Boveri also observed an immense intensification of a feeling of life through the constant presence of death.Footnote 95 People were hungry and cold, but there was plenty of amusement—especially dance bars in the ruins of Berlin.Footnote 96 Heinrich Böll wrote that those “who did not freeze, stole.”Footnote 97 The Catholic Cardinal Frings of Cologne relativized the Seventh Commandment—Thou shalt not steal—in his New Years’ Pastoral Words in 1946.Footnote 98 According to Hannah Arendt, Germans were toiling blindly to avoid confronting themselves with past atrocities.Footnote 99 Jähner writes that the currency reform of June 21, 1948 led to an immense feeling of optimism, and that this reform—not the establishment of the new Basic Law in 1949—was what many for a very long time considered the “big bang” of the Federal Republic of—West—Germany.Footnote 100 He contemplates that the learning processes Germans went through after the war took place in social practices void of concepts, rather than through political reasoning. A political consciousness was formed in the collapse, in the black market, through the rush of displaced persons, in the laborious negotiation of egotistical conflicts, and less in the debates on the value of freedom and the Basic Law.Footnote 101

In 1953, Chancellor Adenauer appointed Hans Globke, a Nazi-lawyer, who had coedited the Nürnberg racial laws, as head of the Chancellery, justifying it with a sentence to become famous: “One does not do away with dirty water, as long as one does not have clean water.”Footnote 102 Universities had experienced several interventions by the Hitler state, and had almost fully capitulated to the Nazi-ideology, and become completely untrustworthy. However, they did not lose their self-confidence after the war. The responsibility of the German elites after the war was characterized by very limited self-criticism.Footnote 103 The German “economic miracle” took off from the mid-1950s. History became strongly politicized and has continued to be so.Footnote 104 German Jewish judge and prosecutor Fritz Bauer—1903 to 1968—was instrumental in Israel’s post-war capture of former Holocaust planner Adolf Eichmann, and he played an essential role in starting the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which began in 1961. A fictionalized German film on these processes Im Labyrinth des Schweigens—direct translation In the Labyrinth of Silence; English title Labyrinth of Lies—was released in 2014.Footnote 105 It demonstrated the late 1950s culture of repression of memory, and the silence of those directly involved, but also the antipathy of the majority of the judiciary, who tried to avoid cases against those responsible. In 2015, another film on Fritz Bauer was released Der Staat gegen Fritz Bauer—The State against Fritz Bauer.Footnote 106 Bauer had been in exile in Denmark and Sweden, and was buried in Gothenburg. In a twenty-first century manner, this film focused noticeably on Bauer’s homosexuality—while a refugee in Denmark—and that of a younger staff in a post war period when homosexuality was still criminalized.

Figure 8. Felix Nussbaum (1904–1944), Self-portrait with Jewish Identity Card, Museum of Cultural History, Osnabrück.

On this background the 1968 “cultural” or “youth revolution” in Germany became a harsh confrontation between a postwar youth and its parent generation, who had all in one way or another been involved in—and to some extent responsible for—the German disaster of World War Two. The novel by Siegfried Lenz, Deutschstunde—The German Lesson—, was published in 1968 and criticized the blind loyalty and obedience against a superior authority of the father of the nineteen-year-old protagonist, Siggi.Footnote 107 In 1968, it fed into a generational conflict related to the concealment and repression of personal and societal responsibility by the now parental generation for the atrocities of the past. Already in 1971, it was filmed for a two-part television series and released again as cinematic film in 2019, signaling perhaps a renewed reflection over the past.Footnote 108

In 1982, Helmuth Kohl, the Christian-Conservative and long-lasting chancellor had come into power. The times were more conservative, and especially in the USA and the UK, also years of emerging neo-liberalism. Glasnost was on its way and finally led to the collapse of Soviet socialism and end of the cold war. The so-called Historikerstreit in the late 1980s dealt with the question of how Shoah or Holocaust should be evaluated forty years after World War Two. This “conflict of historians” started with an article published in 1986 by conservative historian Ernst Nolte, who compared Hitler’s “racial murder” to the “class murder” of the Bolsheviks. This led to a long controversy where especially Jürgen Habermas played an influential role and criticized Nolte’s legitimization of the German genocide. Nolte’s views have to some degree been taken over by right wing extremists in the 21st century.Footnote 109

Seen from outside, it seems as if the “East German Revolution” and/or the “fall of the Berlin Wall” after the “German Unification” in 1989–1990 led to a kind of relativizing of the West-German responsibility for the atrocities of Nazi Germany. A contested concept emerged, the Doppelte Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which addressed both the Nazi-dictatorship and the GDR dictatorship,Footnote 110 or what was also called a “work up” of the Nazi past and the communist past.Footnote 111

K. Memory Culture—Towards New Time Regimes?

One of the most well-known and acknowledged German academics, who has dealt with the German past, and especially with “memory culture”—Erinnerungskultur—is Aleida Assmann. She was born in 1947, studied Egyptology—and later English—and, in 1993, became a professor of English and literary studies. Her work has focused on cultural anthropology and since the 1990s especially on Cultural and Communicative Memory. She distinguishes between individual, social, and collective memory, and her thesis is that individual memory is created in interaction with groups—Wir-Gruppen or Us-groups. Individual and group memory is constituted by what has left deep emotional impression. Emotions contribute to stabilization of memory, and the selected memory contributes to strengthening of the identity. Social memory is short-term memory and dissolves after some time, while collective memory is stable and established to last for longer periods. The difference between short-term and long-term memory relates to, what she calls “memory media.” The media of social memory is dialogue and conversation, and feeds on communicative exchange. Collective memory reduces events to mythical archetypes and, through it, mental images become icons and narratives become myths. Their major importance is their persuasive power and their affective and effective power. They will last until they become dysfunctional. A cultural memory is a long-term memory, which is dependent on institutions such as libraries, museums, and archives. If nations are short lived, institutional and national memory may, to some extent, be more short lived than social memory.Footnote 112 She does not discuss the implications of these types of memories for legal cultures, but under specific conditions, they will probably all be important for norms, values and attitudes of individuals, communities and societies.

In 2020, Assmann’s German language book from 2013 Ist die Zeit aus den Fugen? Aufstieg und Fall des Zeitregimes der Moderne, was translated into English as Is Time Out of Joint? On the Rise and Fall of the Modern Time Regime.Footnote 113 The first part of the title is a paraphrased quote by Shakespeare’s Hamlet, who after having met his father’s ghost declares that “the time is out of joint—O cursed spite, that ever I was born to set it right.”Footnote 114 As Assmann continues, Hamletalone must bear the burden that “the time is out of joint” and he takes on the task of sorting out.Footnote 115

Figure 9. Hamlet quote at University Square, opposite Martin Luther University, Halle.

Her view that the modern time regime is on the decline is of general importance in the Western world, where it is particularly influential in all aspects of life and culture, including legal culture. She claims that there is a

“… more general sense that the future is no longer much of a motivator in the arenas of politics, society and the environment. Expectations for the future have become extremely modest. Within a relatively short period of time, the future itself has lost the power to shed light on the present, since we can no longer assume that it functions as the end point of our desires, goals or projections. We have learned from historians that the rise and fall of particular futures is in itself nothing new. However, it is the case not only that particular visions of the future have collapsed in our own day, but also that the very concept of the future itself is being called into question.”Footnote 116

She explains this with the depletion of the resources of the future, of natural resources, ecological degradation, climate change and water crisis, along with demographic problems such as overpopulation and aging societies. The rhetoric of progress has a diminished hold on the public imagination, and the future has become a site of anxiety, which must be tended to responsibly.Footnote 117 According to Andreas Huyssen, quoted by Assmann, this shift seems to have taken place since the 1980s, as a shift of focus from present futures to present pasts.Footnote 118 She introduces the

“notion of a cultural time regime to refer to the shift in temporal ordering that accompanies this reorientation. All time regimes provide a groundwork for unspoken values, interpretations of history and meaningful activity. With the idea of time regime I mean to suggest a complex of deeply held cultural presuppositions, values, and decisions that guide human desires, action, emotions, and assessments, without individuals’ necessarily being aware of these foundations.”Footnote 119

These reflections seem to me to be of utmost interest and importance not only for a German memory culture but also for contemporary western culture at large, including legal culture. However, their impact and implications probably need to be considered more in detail.

L. Literary and Popular—Legal—Culture

One of the major authors of the twentieth century, whose work reflects the many and changing societal and mental conditions in a changing Germany, is Thomas Mann (1875–1955). In this context, I will refer to three of his novels, Buddenbrooks. Verfall einer Familie (1900),Footnote 120 Der Zauberberg (1924),Footnote 121 and Doktor Faustus (1947).Footnote 122 Some of his work has been described as belonging to a “genre” of “decadence literature,” which was particularly important in France after it lost the war against Germany in 1871.Footnote 123 In Buddenbrooks,Footnote 124 published when Mann was only twenty-five, he describes the “small scale” and gradual downfall of a family from the North German important and historical trading city, Lübeck. One may perhaps claim that “the fall of the (bourgeois) family” precedes the social, cultural, and legal transformation, which was already taking place around the beginning of the twentieth century. The downfall precedes a transformation, which in the German case was particularly strong and important in the decades to come.

In 1905, Thomas Mann married Katia Pringsheim (1883–1980), granddaughter of Hedwig Dohm (1831–1919), a highly prominent German “Frauenrechtlerin”—or Woman’s Rights activist, who lived long enough to experience women achieving voting rights in 1918. Both came from affluent families of Jewish background, but Katia did not at all share her grandmother’s political activism and interest in women’s rights, neither to be educated nor to vote.Footnote 125 Due to exhaustion, Katia Mann went to stay in Davos at a tuberculosis sanatorium for wealthy patients, where Mann visited her in 1912. Some of his impressions there—shortly before the beginning of World War One—led him to write the huge novel Der Zauberberg. The Magic MountainFootnote 126 which portrays both the bewilderment of an individual, Hans Castorp, and the fall of imperial bourgeois societies. The bourgeois civilization and environment was situated in aloof isolation and a very distant position to the rest of the world—especially the “lowlands” of Northern Germany and Hamburg, the hometown of Hans. To some extent, one might also say that this is a place, where “time is out of joint.” The novel is divided in seven chapters, where the first five chapters deal with Hans’ first year in Davos —revealed as 1907—, while the last two chapters concern the last six years. The topics of the book are thus time itself, as well as health, illness, sexuality, and mortality, besides ongoing conversations on general and political topics. The originally very slow pace gradually gives way to a very compressed description of life and developments, ending when Hans signs up as a soldier in World War One, leaves Davos, and is killed on the first day of the devastating war.

The downfall of the bourgeois family, the disintegration of Western/German bourgeois culture, and the breakdown of the militarized German Empire provide a cultural context and background for an understanding of the shattering transformations of reality, which took place during the fin de siècle, and in the first dramatic and chaotic decades of the 20th century. These disturbing developments continue in the third novel Doktor Faustus, which Mann began in 1943 during his American exile. It reflects the atmosphere of the emerging Nazi-period through the life and ambitions of the composer, Adrian Leverkühn, born in 1885, who dies in 1940 after ten years of mental alienation. The novel describes a solitary, estranged figure, who expresses the experience of his times in his music: “[T]he story of Leverkühn’s compositions is that of German culture in the two decades before 1930—more specifically of the collapse of traditional humanism and the victory of the mixture of sophisticated nihilism and barbaric primitivism that undermine it.”Footnote 127 In some of the later chapters, 33 and 34, the narrator discusses the era of which he writes—an era of state collapse, capitulation, exhaustion, and vacuum after the passing away of the old—military—authority after 1918. Mann, through the narrator, discusses traces of an apocalyptic culture. A special continuation of Chapter 34 discusses the difficulties of Germans to handle the Republic, and the almost ironic reflections on the jurisprudence and legal philosophy of this time:

A jurisprudence that wanted to rest in popular sentiment and did not wish to isolate itself from the community, could not allow itself to make the point of view of the theoretical so-called truth [which was] contrary to community its own; it had to prove itself as modern as well as patriotic in the most modern sense, by respecting the fertile falsum, acquitting its apostles and letting science pull off with a long nose.Footnote 128

These repeated forms of collapse of family, individual, society, systems, values, and ideas create a context and backdrop of the legal culture(s) of the twentieth century with their chaotic conditions coexisting with earlier “Weltanschauungen” relating to past eras. People live in different eras at the same time, with different ways of perceiving right and wrong—bound by tradition and privilege.

Thomas Mann was, as several other authors, very inspired by the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), who was only later to become the acclaimed philosopher of Nazi-Germany. In 1872, a year after the establishment of the German Empire, Nietzsche wrote in his Über die Zukunft unserer Bildungs-Anstalten that the German spirit was particularly expressed through the German Reformation, German music, the immense bravery and rigor of German philosophy, and the loyalty of German soldiers, newly proven at the time.Footnote 129 Mann’s novels cover the collapse of several of the elements of this German spirit.

In the beginning of the twenty-first century, one of the highest profiled and costly internationally oriented German television series, Babylon Berlin, overlaps with the period covered by Doktor Faustus, especially the years 1928–29.Footnote 130 The third section of the series and its episodes leading up to the economic collapse at the New York Stock Exchange in October 1929, which spreads to Germany and creates havoc, are filmed in a way, where sequences gradually get shorter and shorter and perspectives shift rapidly and chaotically, leaving the viewer with a sense of anxious and fearful horror. One knows what comes, but fears and dreads it nonetheless. In the twenty-first century ideas and ideals, cultures and hopes perhaps again cannot be taken for granted.

One of the authors, who has become an influential voice in Germany since 2009, is the already mentioned defense lawyer and author Ferdinand von Schirach—born 1964. His books and theater plays deal with issues of both historical and contemporary relevance, and are strongly influenced by both his own cases and the format of criminal court cases and hearings. His first book from 2009, Verbrechen—Stories or Crimes. Stories are short stories mainly dealing with topics of the twenty-first century.Footnote 131 They take place amongst others in the Berlin underworld, populated by professional murderers, as well as immigrants and sometimes very bright young men living on different types of crime and speculation. In all their brevity, these stories also reflect the world of the twenty-first century with its migrants, refugees, criminal economies, sex work, economic inequality, and perhaps increasing psychological and mental disturbances. Contrary to the very long novels by Thomas Mann, von Schirach writes short pieces—perhaps addressed to an audience more oriented towards images—which today play an enormous role as the backdrop of a mediatized legal culture. His successful crime novel Der Fall Collini (2011) deals with the murder of a German industrial and the subsequent disclosure of his SS background and hidden history of ordering a reprisal murder in an Italian village in 1944—another piece of “memory” in the legal landscape.Footnote 132 The male defense lawyer is a young German of Turkish origin, who also happens to be a kind of adopted son of the victim of the murder, and emotionally involved with his granddaughter. This novel was filmed and released in 2019.