A. Introduction: On the Need for a Typology

Implicit in any system of multiple constitutional layers—state/federal or state/union—is the existence of a plurality of authoritative legal rulings regarding some constitutional rights. Footnote 1 Within the same system, when one moves from a component jurisdiction to the other, often the existence and the scope of certain rights vary considerably. The plurality originates from the multiplicity of constitutional sources or divergent interpretation of actors within their respective jurisdictions, as well as possible inter-jurisdictional dialogues or conflicts. Some rights are centrally defined and share a uniform core across jurisdictions. Yet, even these centralized rights vary in their degree of centrality, either as minimum, maximum, or others. The commonly used typology to capture the interaction of dual rights is to contrast ceilings with floors. The former refers to rights defined by the center—the union or the federal government—as a minimum protection which the state must adhere to but could diverge above, unlike ceilings which states cannot exceed. Footnote 2

Nevertheless, jurisdictional conflicts, dialogue or limits of both supremacy and judicial oversight often lead to a range of possibilities which go beyond the ceiling/floor dichotomy. As many have noted, the dichotomy is often “confusing,” Footnote 3 or “out of sync” Footnote 4 with how dual rights interact and represents only a “half-truth.” Footnote 5 As will be shown later, areas such as rights of immigrants or those affected by the sovereign immunity doctrine in the US as well as certain rights falling under the EU’s E-Privacy Directive, for instance, do not neatly fall within the floor or ceiling descriptions. Footnote 6 Neither does the centralization/decentralization dichotomy fare better in fully capturing the possible state/center interactions over rights. As will be shown in examples such as abortion in Europe or capital punishment in the US, there exist more nuanced categories and mezzanine levels beyond centralization/decentralization. In both examples, a substantive right is neither defined by the center, nor is the authority of the state thereof absolute. Robust cognizance of these mezzanine levels helps expand the choices “menu” Footnote 7 in the dialogic interaction between the two levels of government and gives more wiggle room for informed structural interactions, particularly in highly divisive rights where the role of central intervention is regularly discussed.

To heed Birks’ memorable warning, “[w]ithout good taxonomy and a vigorous taxonomic debate, the law loses its rational integrity,” Footnote 8 the article offers a more accurate structural classification of the dual protection of rights in the EU and the US. It is structural because its vantage point lies at the intersection of the vertical division of powers and rights, namely, whether and to what extent jurisdiction regarding a certain right is exercised by the center, component state, or concurrently. Seen this way, the purpose of this classificatory attempt is threefold. First, to serve as a comprehensive yet simple connecting theme for comparisons conducted between the vastly dynamic structure of the two-centuries old US constitution and the composite EU constitutional architecture. Following Hohfeld’s remark, when compared subjects are expressed “in terms of their lowest common denominators . . . comparison becomes easy, and fundamental similarity [and divergence] may be discovered.” Footnote 9 To reformulate Varuhas, a “fine-grained" categorization is required for “enriching our understanding” of the two systems and “carrying forward knowledge more generally.” Footnote 10

Second, the typology is of fundamental utility for research engaging with federalism’s “oldest question,” Footnote 11 i.e., which level of government—center or state—is better suited to regulate which type of right and to what extent. Often, centralizing certain rights proves vital by keeping the rights away from the majority’s vicissitudes at the state level. Footnote 12 In other cases, centralization become a “threat” to the nuances of local diversity.Footnote 13 As many have noted, the literature lacks a proper compass to determine which rights are more suitable for centralization and which are not. Footnote 14 For example, in the US, federalism and decentralization “served as a code word” for “racism” for quite some time. Footnote 15 It is universally acknowledged that only after centralization of minority rights did protection of the rights of African Americans significantly improve. Footnote 16 Likewise in the EU, the centralization of equal pay opened avenues for sex equality that were not possible through national systems. Footnote 17 Conversely, a similar move to centralization for abortion in America triggered violence and defiance of state legislations. Footnote 18

Exigences of space preclude overcurious investigation of these complex dynamics regarding abortion, minority rights and others. It suffices to say that reliance on the existing dichotomies may be factually insufficient for a normative assessment of these areas. As the examples below will show, certain rights appear to fall within the central prerogative while states de facto enjoy wide leverage regarding their content. In contrast, other rights that appear to fall within the state’s regulatory power at first glance in fact can lead to reverse centralization through redundancy and convergence. Given that descriptive accuracy is a sine qua non of any normative inquiry, to normatively engage with federalism’s boundary question, the existing incomplete dichotomies of centralization/decentralization or floor/ceiling cannot suffice. Rather, the proposed typology’s more nuanced account of the locus of power over certain rights facilitates tracing the extent to which a change in that jurisdictional venue affects rights protection. This allows an informed assessment of which level of government, the union or the state, is better suited—acting exclusively or concurrently—to regulate which type of rights and to what extent. Seen this way, the typology becomes a needed tool and a requisite for proper engagement with federalism’s boundary question, at least with regards to rights.

The third purpose of the typology stems from the interlinkage between cognitive approaches and comparative constitutional law. In cognitive sciences, it is contended that the human brain finds categorization convenient if not necessary for comprehending the complexity of the world. Footnote 19 As Birks remarked “it is not too much to say that taxonomy is the foundation of most of the science which late 20th century homo sapiens takes for granted. Had he been averse to taxonomy or a bad taxonomist, Darwin would have observed but would not have understood.” Footnote 20 In comparative constitutional law, Zumabsen reminds us that the field itself was first established by Aristotle’s categorization of different types of constitutional systems. Footnote 21 Likewise, Varuhas criticizes the contemporary public law scholarship by noting that “rigorous legal analysis may elude us without legal taxonomy.” Footnote 22 Perhaps, then, to better approach legal inter-systematic comparisons (between different systems) as well as intra-systematic analysis, a clearly delineated taxonomy may be a first step towards developing a needed tool in examining the interlinkage of rights and division of powers in composite multi-level constitutional structures.

Before proceeding to the analysis, a prefatory note is due regarding the comparability of the US and the EU as well as the case selection rationale. Despite many divergences in details, the two systems share a “normative” denominator Footnote 23 and a “family” resemblance Footnote 24 that have long generated functional comparisons not only in literature Footnote 25 but also in judicial opinions. Footnote 26 This stems from the fact that the US federal structure, like the EU, came into being through a constitutional process of “coming together” Footnote 27 or what the President of the CJEU terms “integrative federalism.” Footnote 28 As many have remarked, in both experiences, pre-existing states voluntarily agreed to integrate into a continent-sized polity. Footnote 29 The multiplicity of “norm entrepreneurs” concomitantly brings an inescapable tension between “uniformity and diversity” within a “unified” constitutional order. Footnote 30 This commonality is what makes a comparison of the two systems “obvious and fruitful.” Footnote 31 The two systems remain thematically “the least different” if not “the most similar” among other possible comparator constitutional polities. Footnote 32

Being the most similar comparators, the case selection method follows what Jackson terms “functional contextualism.” Footnote 33 Given the taxonomical mode of inquiry, Footnote 34 focusing on functions has a potent explanatory force of illustrating the full range of interactions of rights within each jurisdiction, Footnote 35 while contextualism ensures that the necessary particularity of each system is not overlooked. Footnote 36 The selected cases are the ones that best describe and contextualize the function of whether and to what extent the jurisdictional locus regarding rights is allocated to the center, component state, or concurrently. Differently put, the selection criterion is to inquire what jurisdictional options are available in each system for distributing authority over rights, and then to illustrate each option through case law examples. This criterion, as a common denominator, helps navigate the often-labyrinthine regulation of rights within two composite constitutional systems and facilitates identifying convergences and divergences in a manner liable to attain the taxonomy’s previously discussed three-fold purpose.

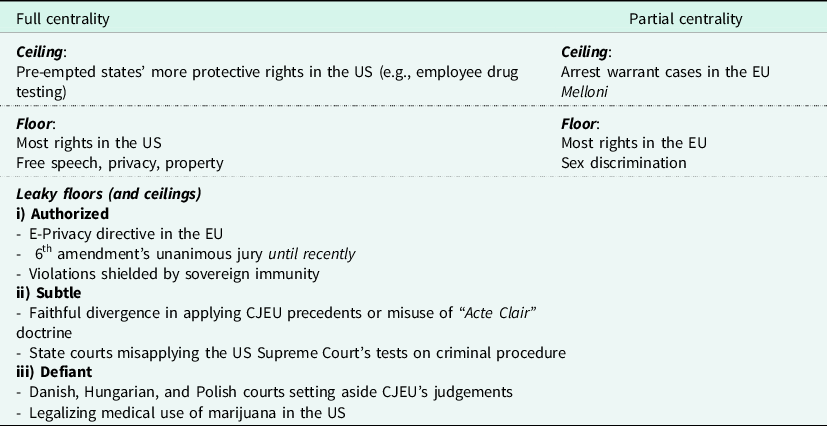

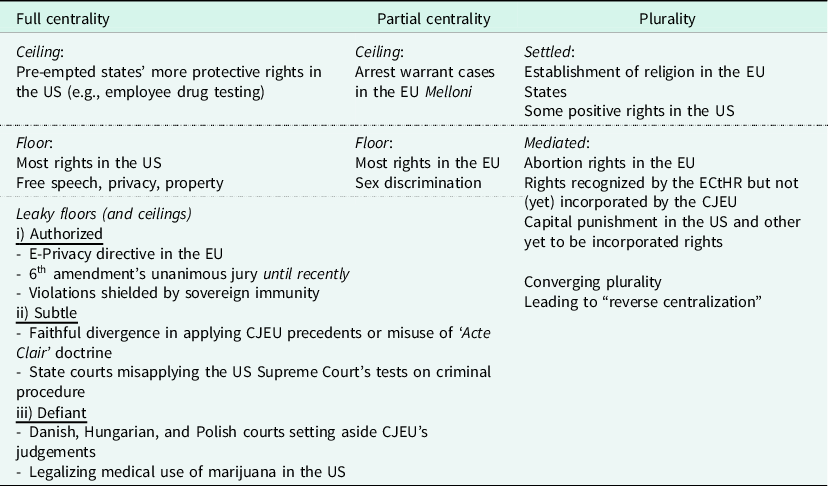

With this in mind, the following classification weds scholarly concepts and judicial terminology from the two sides of the Atlantic while adding necessary refinement substantiated by a wide array of case law. Footnote 37 More specifically, the typology offers a contribution through its differentiation between three broad categories: plurality, partial and full centrality. Within these overarching categories, three sub-species are added to plurality and three to what is termed “leaky” floors/ceilings. Footnote 38 Each part of the classification is explained below with brief comparative examples from case law.

B. Centrality and its Subcategories

Centrality refers to cases where the authoritative rule regarding—at the least the minimum—protection of a particular right is defined top-down. Namely, the right originates from the central authority—the federal authorities in the US and the EU—as interpreted by either the US Supreme Court, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) or the respective central legislator.

Centrality can be full or partial. Full centrality is typically exemplified by the US Bill of Rights after its “incorporation” in the twentieth century. Since then, rights contained in the bill once incorporated by the US Supreme Court must be considered, at least as a minimum protection, by state courts. Footnote 39 This is irrespective of whether the case involves a purely internal state or inter-state matter. Footnote 40 The extent to which such rights are binding upon states, as minimum or maximum, will be explained later while contrasting the sub-categories of centrality.

Partial centrality is less straightforward. It occurs when the rights defined by the center are applicable before state courts only within a defined scope, but not in all cases. This reflects the current situation in the EU. There, fundamental rights bind component states only when they act within the scope of EU law but not in “purely internal situations.” Footnote 41 Partial centrality also describes the case of the US Bill of Rights before incorporation; when state courts would only enforce the Bill when they applied federal laws. In the contemporary US, partial centrality exists in yet-to-be incorporated rights or when a federal act regulates part of the field while leaving the remainder to states. An example is the Wagner Act which applies to certain private-sector employers with inter-state activity but not to state officials, employees of religious organizations, agricultural or domestic workers. Footnote 42 Thus, the statutory right to strike contained in the Act does not apply to the latter categories and states remain free to diverge in regulating it beyond the Act’s reach. Footnote 43

Three notes on partial centrality are due. First, there have been rare occasions where the centrally defined right has only bound component states, but not the central authority. For example, the Equal Protection Clause in the American Constitution added after the Civil War clearly addressed the state and not the federal government. Yet, in 1956, the court extended the “Equal Protection” clause to the federal government. Footnote 44

Second, a right which is partially central is on the other side partially plural. An example from the US is the already mentioned Wagner Act. Given that the scope of this federal act does not extend to public employees, regarding the latter states are free to diverge on this issue. Therefore, one sees a “minority of states” recognize, with varying degrees, the right to strike unlike most states which indeed prohibit their officials therefrom. Footnote 45 Stated differently, the right to strike can be seen as partially central yielding one authoritative legal answer—for private workers—and the other part is plural displaying a variety of answers—for different states’ public employees. Footnote 46

Examples abound in the EU, as the constitutional habitat of partial centrality. When the CJEU first introduced indirect sex discrimination, this centrally defined right was and is still “partially central” applying upon Member States only with the scope of EU law. In purely internal situations, the domestic systems of Member States diverged starkly on banning that form of discrimination. In fact, it was only the UK which internally recognized the concept. Footnote 47 Although, over time, the concept has “migrated” into the domestic systems of most of the EU states, Footnote 48 the conditions of what constitutes indirect discrimination and burden of proof vary considerably in domestic litigation in each jurisdiction. Footnote 49 Another example is voting rights of Union citizens or “second country nationals,” namely, citizens of one of the EU Member States residing in another. Footnote 50 EU law has centralized a right to second-country nationals to vote in municipal and EU elections—but not national elections—in their state of residence. Footnote 51 Nonetheless, beyond this centrally defined sphere, EU states diverge on enfranchising EU residents in national elections. Plurality in this regard is clear when contrasting the few states, such as Ireland, which endow classes of second country nationals with the right to vote in national elections, while most of the Member States either significantly restrict or completely exclude this right. Footnote 52

Thirdly, partial centrality is not one-size-fits-all. The extent to which a partially centralized right applies to component states may vary depending on the right in question. The point can be illustrated by contrasting racial discrimination as protected by the Race Equality Directive (RED) Footnote 53 vis-à-vis discrimination on grounds of religion or belief and other grounds protected by the Framework Equality Directive (FED). Footnote 54 While both directives are partially centralized and thus only apply to member states within the scope of EU law, RED has a much broader scope of application which extends beyond employment-related fields to include social protection, healthcare, education and supply of goods and services such as housing. Footnote 55 Conversely, FED applies only in the context of employment. Accordingly, while EU protection extends to banning the denial of services to a member of a racial minority, EU law does not apply to denying services or goods to someone manifesting a religious symbol, be it a Sikh turban or a Jewish yarmulke. Footnote 56 Instead, the situation is governed by the divergent national rules.

Bearing this in mind, this article next examines the subcategories of centrality. Both full and partial centrality is divided into three sub-categories: Floor, ceiling, or leaky floors/ceilings.

I. Central Floor

Here the central interpretation serves as a “safety net” or a “minimum protection” to which the component state must offer equivalent or more expansive protection. Footnote 57 This is the classical category in which most rights fall. As is well known, it was Justice Brennan’s famous 1977 article that brought the “floor” metaphor to the foreground of academic and judicial analysis. Footnote 58 The article ushered in an era of “new judicial federalism” which stresses the role of state constitutions and courts as “guardians of liberty” in offering a stronger protection of fundamental rights. Footnote 59 To harken back to the typology, the case of centrality can be either full or partial, and so can the category of floor. Below, examples from the US on full central floor is contrasted with that of the EU’s partially central floor.

Examples of fully central floor in the US include state courts and constitutions bestowing more expansive protection than the federal equivalent in the area of freedom of expression. Unlike the state action requirement by the US Supreme Court whereby this freedom is only vertically enforceable against governmental bodies, two state courts have extended the freedom horizontally against private colleges. Footnote 60 In the protection against “unreasonable searches and seizures,” where the Supreme Court accepted warrantless search of garbage waste, Footnote 61 many state courts extended constitutional protection to garbage. Footnote 62 Multiple examples exist in the areas of property rights Footnote 63 privacy Footnote 64 and others. Footnote 65 Indeed, an empirical study showed that one out of three state court judgements expand rights beyond the federal floor. Footnote 66

The EU offers many examples on partially central floors. This includes the directive which sets the minimum period for maternity leave at 14 weeks, with 2 weeks compulsory leave before and/or after confinement as well as adequate allowance subject to national legislation. This aligns with the Charter right enshrined in Article 33(2), to reconcile family and professional life. The directive sets only a floor as many Member States have gone above the prescribed period of paid leave, including up to 52 weeks. Footnote 67 Åkerberg Fransson provides another example, where the applicant claimed a violation of the right against double jeopardy “ne bis in idem” for being prosecuted under Swedish law on account of a tax offence for which he had already been subject to administrative penalties. The CJEU, after establishing its jurisdiction, set only a floor of the right, leaving it to Member States to provide higher standards. Footnote 68

Notably when the floor is not leaky, as discussed later, a key difference exists between a partially central floor and a full one. In the US, when states diverge in their expansion above the floor, it remains a one-way ratchet above the floor. Whilst this is true in the EU Member States when acting within the scope of EU law, it is not the case regarding purely internal situations. There, states are not limited by a one-way ratchet and are free to diverge both above or under the equivalent EU floor as in the previously mentioned cases of indirect discrimination or non-citizen voting where certain states have denied the right altogether in domestic situations.

II. Central Ceiling

The ceiling as a maximum prevents states from granting more generous protection. Surely, due to the US Supremacy Clause, this is the norm whenever state courts are applying federal law or the federal constitution. State courts are generally free to interpret their equivalent state rights more generously but not free when they are applying federal the Bill of Rights or federal laws. Footnote 69 In the case of the latter, they must follow and not expand the US Supreme Court’s interpretation, otherwise they risk reversal. Footnote 70 That obvious scenario aside, ceilings also exist when state courts are interpreting rights under their own constitutions and laws which can be trumped by a less protective federal provision.

For example, California’s constitutional provision on privacy was held to be pre-empted by the federal law mandating random drug testing for employees which adheres to a lower standard of privacy. Footnote 71 Another example is where California attempted to protect the feelings of its residents of Holocaust survivors and their descendants by passing an act which required insurance companies doing business in the state to disclose information concerning policies sold in Europe between 1920-45. Yet, the US Supreme Court found the act to be pre-empted by executive agreements and dormant foreign power. Footnote 72 Other examples abound. Footnote 73

In the EU, Melloni is the canonical example of a partially centralized ceiling. The more protective Spanish constitutional principal barring extradition for a conviction in absentia was set aside for the enforcement of the less protective European Arrest Warrant. The defendant, Mr. Melloni, a resident in Spain, was subject to an arrest warrant issued by Italian authorities based on a conviction in Italy which was in absentia, yet he was represented by two trusted lawyers. Trying to avail himself of the more protective constitution, he challenged the warrant for breach of the fair trial principle of the Spanish Constitution. The Spanish Constitutional Court lodged its first preliminary reference to the CJEU on whether Article 53 Charter allows, in this case, the overprotection of the right to a fair trial by the Spanish Constitution. The CJEU replied negatively on the premise that the EU states’ more protective rights would undermine the “primacy, unity, and effectiveness” of the Warrant system. Footnote 74

III. Leaky Floors/Ceilings (Rights Derogations)

The ceiling/floor dichotomy does not cover the full province of rights falling within centrality, rather there is an important further sub-category conceptualized as leaky floors and ceilings. Footnote 75 Often termed a right “derogation,” a federal “discount,” Footnote 76 this category denotes cases where the component state’s protection of a given right can go below the central floor or, less frequently, above the ceiling. This derogation/leak could be either 1) authorized, 2) non-authorized yet subtle, or 3) openly defiant.

1. Authorized Leaks or Derogations

These are derogations which the center explicitly acknowledges and permits. This category usually involves derogation below-central floor. It can be illustrated by the US Sixth Amendment’s jury requirement. Until very recently and for almost half a century, the US Supreme Court used to ordain unanimous jury in federal convictions but held that states, if they wished, could provide for “less-than-unanimous” jury convictions. Footnote 77 Another is the sovereign immunity doctrine. With some exceptions, the doctrine is understood to bar private action before federal courts against state governments for monetary redress. Footnote 78 This often leads to constitutionally authorized situations of a right without remedy. This, for instance, was the fate of Patricia Garrett who was fired by the University of Alabama for undergoing cancer treatment; while the state action violated the federal disability law, she still could not sue the state to remedy the violation of her rights. Footnote 79

In the EU, certain instruments often authorize Member States to go below the floor of certain rights. A fitting example is the E-Privacy Directive which in Article 15(1) authorizes Member States to “restrict the rights in that Directive relating to the confidentiality of communications, location and other traffic data and caller identification.” Footnote 80 This authorized derogation is conditioned on being “a necessary, appropriate and proportionate measure within a democratic society to safeguard national security defense [and] public security.” Footnote 81

The center could also authorize a margin of derogation above the central ceiling which is often termed a “leaky virtue.” Footnote 82 This occurs less frequently, and it is often less clear. An example from the US comes from the field of so-called “environmental federalism” or “environmental rights.” The Clean Air Act empowers the U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to set a “ceiling” standard which pre-empts states from adopting their own. Footnote 83 Still, the act allows California to apply for a waiver of this pre-emption whereby it could adopt more environmentally protective standards than that of the EPA. Footnote 84

2. Subtle Leaks or Underenforcement

This refers to “modest” yet sometimes consistent “deviations” which are neither expressly authorized nor openly defiant. They originate from a loose reading or often misinterpretation of the central law, or the central court’s multifactorial formulas by state courts which, intentionally or unintentionally, lead to “below-the floor” or less often above-the-ceiling protection. Footnote 85 A main reason behind this category is the difficulty of policing the central interpretation due to legal and logistical limits of appeal, as in the US Footnote 86 or the lack of it altogether in the EU. This leaves room for deviations that do not amount to “extreme malfunctions” or overt defiance to the central authority. Footnote 87

In the US, the rights of criminal defendants represent a ripe field of these sorts of leaks. Footnote 88 A stark example is the right to counsel. In Gideon and its progeny cases, The US Supreme Court held the Sixth Amendment to require state-funded counsel for indigent criminal defendants facing jail or prison. Footnote 89 In practice, consistent leaks at state level made this right “diluted” Footnote 90 and varied across jurisdictions well below the constitutional floor. Footnote 91 Thousands of Americans every year are jailed either with “no lawyer at all” or with a lawyer who does not have “the time, resources, or . . . the inclination to provide effective representation.” Footnote 92 A host of practical factors contribute to this outcome. Chief among these is the difficulty of meeting the test to establish allegations of inadequate counselling which are usually reviewed “with deep deference.” Footnote 93 Another factor of the de facto lower protection unexamined derogations is the limited post-conviction habeas corpus review, which in the Supreme Court’s words is limited to “extreme malfunctions in the state criminal justice systems” rather than “ordinary” errors. Footnote 94

In the EU, subtle leaks are bound to occur. One reason is that after referral, national courts enjoy a wide discretion in applying the CJEU test with no review, except indirectly and infrequently through state liability or even less through infringement procedures. Thus, as many have noted, while overall compliance with CJEU’s rulings is high, Footnote 95 the interpretation of national courts do not always uniformly align with the CJEU’s. Footnote 96 Another factor is the lack of monitoring mechanisms of the well-known “acte clair” doctrine. According to which national courts of last instance are not obliged to refer questions to the CJEU where the correct application of EU law is clear and leaves no room for “reasonable doubt.” Footnote 97 The subjective nature of interpreting “reasonable doubt” often leads to “faithful” cross-national divergence in applying the relevant EU norm, be it floor or ceiling. Footnote 98 To guard against this and given the prohibitive political cost of the infringement procedure against judicial errors, the main available alternative is state liability in damages which extends to breaches of EU law by national courts. Yet, state liability is a rather “uncertain mechanism” Footnote 99 as it is confined to – in the CJEU’s words – “the exceptional case where national court has manifestly infringed the applicable law.” Footnote 100 This formulation seems reminiscent to that of the US Supreme Court on “extreme malfunctions” rather than “ordinary errors.” Footnote 101

A classic example is offered by Sweet on “discrepancies between the CJEU's requirements and how the national judges actually decide cases.” Footnote 102 When the CJEU, through a famous line of cases, established a multi-step framework on indirect discrimination, cross-national variation existed in its application. Footnote 103 In 2018, the EU Commission published a thematic report on cross-national protection against dismissal and unfavorable treatment in relation to the take-up of family-related leave. The report showed that despite the existence of “clear formal statutory rights implementing at domestic level the rights laid out in EU law,” there was often “variation” and “gaps” in enforcement at national levels. Footnote 104 Another example is the discrepancy across jurisdictions in defining the “duty” of reasonable accommodation for disability in the workplace underlying the relevant EU directive. Footnote 105 What is notable here is that national courts do not defy or call into question the particular EU right. Rather, they diverge – often faithfully – due to what Resnik terms “erratic failure” in interpretation or the complexity of “norm implementation.” Footnote 106 Other examples abound. Footnote 107 Succinctly put, what distinguishes these types of leaks is that they are neither explicitly authorized by the center as those of the former type, nor purport to openly challenge the central rules as in the type discussed next.

3. Defiant Leaks

As the name suggests, they represent derogation which is done openly in resistance to the supposedly supreme central norm or judicial precedent. Given the conflicting views on supremacy in the EU, defiant leaks are predominantly judicial in nature. Examples include the Danish Supreme Court’s “Ajos” judgement refusing to follow the CJEU’s decision on the horizontal application of age discrimination. Footnote 108 Similarly, the Hungarian Supreme Court refused to follow CJEU’s judgement on the relocation of asylum seekers. Footnote 109 The vast literature on the European courts’ defiance is well-known and needs no further explanation here. Footnote 110

Defiance in the US, conversely, is usually initiated by state legislators and succeeds only under certain conditions. Footnote 111 An example is the medical use of marijuana. The Congress enacted across-the-board criminalization of all uses of marijuana including its medical consumption. Whilst, in Gonzales, the US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the federal ban, this did not stop the majority of states from resisting the federal authority and legalizing medical and often recreational uses of marijuana. Footnote 112 Some states even bestowed a statutory “right” to the reasonable accommodation of employees’ prescribed marijuana consumption. Footnote 113 Another example is the ongoing saga of the so-called “sanctuary” states and cities which are providing safe havens bulwarking and expanding the rights of undocumented immigrants in defiance of restrictive federal regulation. Footnote 114

With this, the article has covered the two types of centrality with their sub-categories of floor, ceiling and three sorts of leaks. The following table summarizes the discussion thus far. The article proceeds next to illustrate the remainder category of “plurality” and its sub-categories.

C. Plurality and its sub-categories

Plurality refers to cases where the definition of fundamental rights originates in state constitutions, laws, or jurisprudence. Given the multiplicity of component states, the same question often yields a plurality of authoritative answers. Free healthcare, education, or religious accommodation each can be a constitutional right in one of the component states but not in the other. What distinguishes the nature of these rights and those existing in traditional nation-states is, first, the potential role of the center which can be either an embodiment of a specter of centralizing the pluralized right—threatened plurality—or, have no direct role in cases when plurality on this particular issue is grounded in the central constitution or in long-established practice—settled plurality. A second difference is cross-fertilization among sister-states where rights can converge and migrate both horizontally and bottom-up—converging plurality. The three types are explained below with relevant examples.

I. Settled Plurality

This refers to rights falling under the state jurisdiction which are insulated from the risk of “competence creep” by the center. The settled nature may be owed to either a constitutional provision, drafting history, settled judicial or political practice. A suitable EU example is the right against the establishment of church-state relationship which is undisputedly well beyond the EU’s reach. Member States vary from the strict French laïcité to states with constitutional reference to the “Holy Trinity” Footnote 115 or even with established state churches. Footnote 116 The insulation from EU’s intervention in this realm can be inferred from, among other things, the fierce drafting debates regarding the reference to “God” or “Christianity” in the Lisbon Treaty or the ill-fated Constitutional Treaty Footnote 117 as well as the contemporary Art 17(1) TFEU which reads, “[t]he Union respects and does not prejudice the status under national law of churches . . . in the Member States.” Footnote 118 It is simply unimaginable that the CJEU would, as its American counterpart did, incorporate a non-establishment right on its Member States forcing them to adhere to a minimum level of separation and to restructure their institutions accordingly.

As per the US, examples include positive or state-peculiar rights protected under state constitutions with no federal equivalence. These include the right to revolution, Footnote 119 the right to hunt and fish, Footnote 120 the protection from private discrimination based on political views, Footnote 121 and many social and economic rights. Footnote 122 The US constitution is a product of an era preceding the emergence of social rights or the so-called “second generation rights” which are, thus, absent from its text. Footnote 123 The US Supreme Court’s approach Footnote 124 and the “common wisdom” among scholars largely suggest that it is highly unlikely that the Court will venture into centralizing any of these rights. Footnote 125

II. Threatened/Mediated Plurality

In this category the competence over a certain right lies within the component states whose courts and legislators are free to vary as to the existence and scope of the given right. Their freedom, however, is neither indefinite nor unqualified, rather there is a potential that the center could extend its reach through the inescapable federal phenomena of “competence creep.” Fundamental rights are particularly prone to serving as a “federalizing force” due to the openness of their provisions as well as their underlying claims to universalism. Footnote 126 While the center may not intervene to impose a definition of the right, it can enact certain procedural checks to ensure the proportionality and coherence of the regulatory scheme of states.

In the US, threatened plurality covers many fundamental rights which have not yet been recognized by the US Supreme Court. In some areas, it is still possible that the Court, at any moment, could intervene to recognize the right in question, thus rendering it centrally binding on all states. Consider, for instance, state divergence for decades over the right against excessive fines until the US Supreme Court incorporated the right in 2019. Footnote 127 Capital punishment is a continuing example. After the Supreme Court’s “four-years moratorium” from 1972 to 1976, Footnote 128 it affirmed that the death penalty is not “categorically impressible” and, with some conditions, states are free to abolish it, as a few did, or retain it as did the majority. Footnote 129 Nevertheless, the Supreme Court occasionally intervenes and invalidates the punishment for certain types of crimes—rape of an adult Footnote 130 or a child Footnote 131 —or for certain offenders—juveniles, Footnote 132 the insane Footnote 133 and the intellectually disabled. Footnote 134

In the EU, for instance, abortion was, and remains, one of the areas where the EU does not exercise jurisdiction. Yet, the issue made its way to the CJEU in Grogan. Due to the then-Irish constitutional ban on abortion, an injunction was sought against an Irish student union to restrain the distribution of handbooks containing information about the legality of abortion in the UK and available clinics therein. The student union, in their defense, argued that the injunction constituted an obstacle to the EU’s freedom to provide services. The CJEU dismissed the case on formality without pronouncing on the right to abortion leaving it to the plurality of states. At the same time, however, it sent a credible threat to induce cooperation from Irish courts by classifying abortion as “a service within the meaning of the EECT” Footnote 135 which threatened future extension of it within the CJEU’s reach. The threat might have been heeded in Ireland which after a long-time legalized abortion. Footnote 136

The peculiarity of the EU having what Schütze terms an “external” bill of rights, Footnote 137 namely, the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) must be acknowledged. It also behooves the inquiry of how a decision on fundamental rights by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) affects the structure of rights within the EU and the proposed typology. It might be of value to discuss this matter further. One caveat is that the comparison concerns the constitutional rather than the international effect of ECtHR rights. Namely, it is limited only to EU member states and in the cases where ECtHR jurisprudence enjoys direct effect and supremacy vis-à-vis national law.

As is well-known, the ECHR is an international human rights treaty predating the EU which has its own international court, the ECtHR. Footnote 138 While all EU Member States are signatories thereto, the EU itself is (still) not a member. Footnote 139 Therefore, the convention is not EU law nor is its court’s jurisprudence formally binding on the CJEU as it has consistently affirmed, Footnote 140 notwithstanding the fact that ECtHR exercises an indirect review of EU acts through Member States. Footnote 141 As an international agreement, ECHR only binds its members under classic international law. Footnote 142 Therefore, states remain free as to “which domestic legal status” to bestow upon this international convention. Footnote 143 In fact, as Krisch showed, a majority of member states’ supreme courts have declared themselves not constitutionally bound by ECtHR rulings. Footnote 144

Whilst it is true that Article 6(3) of the TEU affirmed that the ECHR may serve as a source for the discovery of general principles of EU law, it does not follow that the ECHR may prevail over conflicting national law or produce direct effect, Footnote 145 unless state constitutions have so chosen. Footnote 146 Nor does Article 52(3) of the Charter read as an obligation by the CJEU to follow the jurisprudence of the ECtHR. Rather, the article encourages “a constructive dialogue” between the two courts. Footnote 147 Accordingly, ECtHR’s decision on a given right would be duly considered by the CJEU but would not be part of the EU law unless the CJEU decided to borrow it in a given case. As case law shows, however, on the one hand the CJEU often converges with ECtHR in a time-honored fashion. Footnote 148 This is seen in the belated recognition of the right to silence for example. Footnote 149 On the other hand, the CJEU conflicts Footnote 150 and diverges from ECtHR in other instances. A recent example of divergence is seen in the case of surrogacy. Footnote 151

Simply put, an ECtHR decision that recognizes a certain right within an area of threatened plurality may have a “catalyst effect” Footnote 152 by strengthening the prospects of centralization through its recognition by the CJEU. This could consequently change the right’s structural location from state plurality (afforded varying positions of ECHR under different national laws) to central floor or ceiling, enjoying the direct effect and primacy of EU law. Footnote 153 Still, centralization is not necessary and remains a threat subject to the CJEU’s discretion and keenness on its “ultimate authority” and the “unconditional primacy” of EU law. Footnote 154 This zeal for autonomy is evident in the CJEU’s recent Opinion 2/13 blocking accession to the ECHR; as well as the recent study of the EU parliament which shows CJEU’s tendency towards increasing reliance on the autonomous interpretation of the charter as the source of fundamental rights with lesser reference to the ECHR. Footnote 155 In short, a right pronounced by the ECtHR remains within the realm of threatened plurality across Member States based on their varying regulation of the domestic effect of convention rights, but if the CJEU decides to incorporate it, then it travels to the centrality and primacy of EU law. Footnote 156

The catalyst effect of ECtHR becomes clearer by harkening back to abortion. Whilst abortion is not an active area of CJEU jurisprudence and the EU demands neither conformity nor harmonization thereof, the ECtHR has developed several procedural checks without fully acknowledging a right to abortion. The ECtHR conceded that courts are not “the appropriate fora for the primary determination as to whether a woman qualifies for an abortion which is lawfully available in a State” because “it would be wrong to turn the Court into a ‘licensing authority’ for abortions.” Footnote 157 Nonetheless, it developed a set of checks once a state opted for a certain regulatory choice, be it more oriented towards pre-natal life or decisional autonomy. Through this, the Court’s jurisprudence ensures that a state’s pursuit of the professed legal and policy aim is coherent, proportionate and clear to the pregnant women. Footnote 158 Locating abortion in the binary categories of “centralization” and “decentralization” would be difficult. The right is neither defined by the center, nor is the authority of the state absolute. Rather, state authority is qualified by the threat of the CJEU’s intervention either by classifying abortion as a service, or by constitutionalizing the procedural checks developed by ECtHR. This may classify the right within a mezzanine level between full centralization or full decentralization.

The existence and the importance of this category has been overlooked particularly in the American debate on abortion which oscillates between the dichotomy of either centralization or decentralization. In Roe the US had centralized abortion, making the federal government/judiciary as the ultimate umpire. Footnote 159 Whereas in Dobbs, the Court has shifted to the other extreme of full decentralization and judicial retreat. Footnote 160 As seen from Dobbs’s judicial opinions Footnote 161 and commentary, Footnote 162 the two sides of the abortion debate entertain either full federal intervention or leave the matter entirely to states, thus placing the mezzanine level of mediated plurality outside their sight. Mediated plurality can be achieved in the US without having an external court such as the ECtHR. Rather, through developing similar procedural checks that the US Supreme Court may invoke to assess the proportionality, coherence, arbitrariness, and transparency of states’ regulatory choices without dictating a certain direction upon states – akin, to some extent, to the Supreme Court’s approach to capital punishment. Footnote 163

In fact, mediated plurality seems to have fared well in the case of abortion in the EU. When Roe was decided in 1973, recognizing the right to abortion across the US, the abortion map in most EU member states was fairly restrictive. Whereas polarization continues in America until today, twenty-five EU states allow abortion upon request, with some divergent details. Notably, there are no major significant attempts to reverse established constitutional principles as is common in American states, neither is the debate fraught with the “fierce” polarization and violence that define the American tale of abortion. Footnote 164

As many have noted, Footnote 165 without imposing a centralized definition, the EU has played an indirectly crucial role in depolarizing abortion and shifting popular opinion. Even in Ireland – one of the more traditionally conservative EU states – being a member of a multilevel constitutional space has made its constitutional abortion banning amendment produce a “cluster” Footnote 166 of litigation not only domestically but also transnationally. The free movement and the continued circulation of women, as many have argued, have improved public deliberation by providing comparison of existing practices of other members in the EU system and accentuated the contradiction and “understated assumption” of national standards and prompted its reconsideration. Footnote 167 Gradually, over a few decades, Irish people have shifted from approving a referendum banning abortion to endorsing the opposite amendment with the same sweeping two thirds vote. More importantly, a balance seems to be struck between the underlying competing values. EU state courts often invoked grounds of social and financial protection to mothers and “student-parents,” measures to encourage motherhood, or to reduce the risk of unintended pregnancies while “also [being] consistent with women’s autonomy.” Footnote 168

Evidence of migration of abortion norms across EU member states abound, be it at the legislative Footnote 169 or judicial level. Footnote 170 It is true that Poland, as the EU’s outlier, has witnessed restriction on abortion recently, but this is part of its unfolding “constitutional breakdown.” Footnote 171 Even there, Polish women are better off than many of their American counterparts. Mothers in Poland are not liable to criminal punishment and the conservative parliament has recently rejected proposals that are easily adopted in American conservative states such as Alabama’s ninety-nine years imprisonment for abortion, or Texas’s recent deputization of private citizens to prosecute abortion providers. Footnote 172

Space precludes a full comparison and analysis of the causes of the starkly different trajectories of abortion in the EU and US. The takeaway here is that the reliance on incomplete categorization unduly reduces federalism’s rich “menu” choices of possible structural options to binary solutions. As in the American examples, discussion is focused on either “centralization” or “decentralization” without entertaining the possibility of “mediated plurality” which in the case of EU states have better harnessed the potentials of federalism in largely diffusing tension over a socially divisive issue.

Differently put, this category illustrates integrative federalism’s capacity to expand the “menu of policy options” Footnote 173 by creating choices that simply cannot be available in federalism’s “unitary cousin.” Footnote 174 Monistic states must opt for and thus impose a top-down ideological choice, which is either liberal or conservatively oriented with their varying versions. Conversely, integrative federalism provides the center, in many issues, with a third option—settled plurality—which is to choose neither, i.e., not to inhibit nor establish a top-down imposed view, leaving each state free to diverge on the issue across the spectrum. Footnote 175 Further, polycentricism offers mediated plurality as an additional fourth option. Instead of federal do-nothingness and relegating the matter fully to states, it keeps the center as a co-mediator to apply procedurals checks examining the states’ regulatory choice without dictating certain substantive outcomes. Footnote 176

III. Converging Plurality

Occasionally, but not necessarily, when the “core” of a right falling under threatened plurality converge horizontally across many states, it can travel bottom-up and get imported by the central court leading to “reverse centralization.” Footnote 177 This not a distinct sub-category of plurality but rather one form which mediated plurality may morph into.

Lenaerts, President of the CJEU, writing extrajudicially has remarked, among others, that when most Member States tend to “converge” on a certain conception of rights, the CJEU is more likely to “follow their footsteps.” Footnote 178 A typical case is Johnston which involved the refusal to renew Mrs. Johnston’s contract as a police officer and to train her on firearms largely on grounds of sex. Footnote 179 The CJEU was asked by the British tribunal to assess the compatibility of the EU directive—Directive 76/207/EEC—with the national provision excluding judicial review over sex equality when a certificate justifying derogation is produced by national administrative authorities. The convergence among many national courts over the rights of effective judicial protection encouraged CJEU to guide the national tribunal to set aside the conflicting national provision. Footnote 180 In another incident, the CJEU filled a lacuna in its jurisprudence through “transposing” a right recognized in a few national legal systems as “lawyer-client confidentiality” declared in AM & S. Footnote 181

Similarly, in the US, Robert Cover identified this convergence pattern a long time ago, Footnote 182 building on Justice Brandies’ conceptualization of federalism as a “laboratory.” Footnote 183 He noted that when a variety of state jurisdictions “independently arrived at a given conclusion . . . [this] reduces the likelihood that the conclusion is a product of local error or prejudice” and this converging redundancy “establishes clarity through iteration.” Footnote 184 An example is Batson v. Kentucky. There, the US Supreme Court overruled its precedent in Swain v. Alabama barring a defendant from proving racial discrimination in jury selection solely on the ground of the prosecutor’s conduct in the case. The Court’s reasoning noted that five state courts had departed in interpreting their constitutions from Swain and thus inspired the Court to change its jurisprudence. Footnote 185 Dean Sager, among others, identified recurring instances of initiating change in a handful of states, growing acceptance by others and finally, extension through the federal government to the remaining states, though often with some resistance. Footnote 186

In fact, the convergence highlights a distinctive feature of dual systems. Some categories might seem unitary in the sense of being defined by one authority, the center—in full ceiling—or the state—in plurality. Yet, horizontal interaction and “redundancy” across sister states enables cross-fertilization where solutions travel “horizontally” from one jurisdiction to the other and “vertically” through reverse centralization, which reshapes the federal ceiling. Footnote 187 A similar point could be made regarding ceiling “leaks” which introduce a layer to an otherwise seemingly mono-layered right, as shown from the discussed cases on leaks.

D. Conclusion

The article proposed a typology of rights in multilevel constitutional structures which distinguished three broad categories: Plurality, partial and full centrality. Within these overarching categories, both partial and full centrality are subdivided into a trichotomy of floor, ceiling, and “leaky” floors/ceilings; with the latter having three forms of leaks. In contrast, plurality is subdivided into settled, mediated, and converging plurality. Each subcategory is demonstrated by examples from both the EU and the US jurisdictions summarized in the table below.

From a structural lens, the typology illustrates the possible interaction between the central constitution and state constitutions in the EU and US. While the two systems diverge in many of their institutional details, they share a “normative” commonality. Footnote 188 Their multiplicity of sovereign actors concomitantly brings an inescapable “tension” between “dispersion and fragmentation” within a “unified” constitutional order. Footnote 189 In such settings, the categorization may prove useful in navigating the often-labyrinthine regulation of rights within two composite constitutional systems. By identifying “lower common denominators” it makes comparison “easy,” whereby “fundamental similarity [and divergence] may be discovered.” Footnote 190

Beyond comparative utility, delineating clear structural categories helps crystallize federalism’s ability to expand the “menu choice” beyond the capacity of unitary states. Rather than inhibiting or establishing one view, federalism allows the center to exercise a third option of “settled plurality” allowing conflicting regulations to exist at state level. It also offers a fourth option of “mediated plurality” where the center applies procedurals check examining Member States’ regulatory choice without dictating certain substantive outcomes. Attention to these additional options eludes many commentators discussing the role of the center in socially divisive rights as seen in America’s abortion debate. Moreover, the descriptive accuracy of a comprehensive taxonomy promises utility as a preliminary step towards more effective engagement with federalism’s “old” boundary question and its quest to normatively examine the interlinkage of rights protection and division of powers in composite multi-level constitutional structures. Finally, as Birks noted, “[a] sound taxonomy, together with a keen sense of its importance, constant suspicion of its possible inaccuracy and vigorous debate on its improvement, is an essential precondition of [legal] rationality.” Footnote 191

Acknowledgements

I am particularly grateful to professors Alison Young, Mark Tushnet and Robert Schütze for their constructive feedback on an earlier draft of this article. The usual disclaimer applies.