By the end of the 1930s, Japan, pressed at home and facing trade barriers throughout Asia, considered a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere its only acceptable political and economic option. A sphere of control in Asia seemed to offer a solution to the acute natural resource poverty of the home islands, to encirclement by European powers and to imminent economic strangulation. Like 1930s Germany, Japan perceived an economic predicament of being a ‘have-not’ nation lacking, unlike Britain and the United States, recourse to the natural resources of an empire. A Co-Prosperity Sphere centred on Japan, it was argued, would create an Asian empire, enabling the Japanese nation to assume its rightful place among the world's great powers.

After highly unsatisfactory negotiations with United States Secretary of State Cordell Hull, Japan decided on war (Ike Reference Ike1967, pp. 254–62). General Tōjō Hideki, not long prime minister, famously summed up the 5 November 1941 Liaison Conference:

[H]ow can we let the United States continue to do as she pleases even though there is some uneasiness? Two years from now we will have no petroleum for military use. Ships will stop moving. When I think about the strengthening of American defences in the Southwest Pacific, the expansion of the American fleet, the unfinished China incident, and so on, I see no end to difficulties. We can talk about austerity and suffering, but can our people endure such a life for a long time? … I fear that we would become a third-class nation after two or three years if we just sat tight.Footnote 1

Finance was the sine qua non of constructing a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. If Japan could not finance the envisaged Asian empire, it could not have it. Japanese resources were by 1941 already badly stretched after being bogged down for four years in an unwinnable war in China. A Japanese war economy had the problem of both financing occupation of Southeast Asia and financing the goods supplied by the region's economies to the Japanese home economy as well as the war effort. How was Japan to deal with these problems?

One main aim of this article is to answer that question for Thailand. The Thai case is particularly revealing because soon after being occupied on 8 December 1941, Thailand allied itself with Japan and was proclaimed by the Japanese as a trusted Co-Prosperity Sphere partner. An analysis of Japanese exploitation methods in Thailand does much to reveal the nature and objectives of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Relevant comparisons between Japanese in Thailand and Nazi strategies in Europe help to illuminate the nature of wartime extraction from the vanquished.

By May 1942, Japan, after a stunningly successful military sweep, had occupied the whole of Southeast Asia, the six countries of Burma, Thailand, Malaya (including Singapore), Indonesia, Indochina and the Philippines. Japanese policy was mapped out before the war. Japan's November 1941 outline of administration in Southeast Asia made this clear: ‘During the war, the great burdens which will fall on natives on account of the acquisition of natural resources and the process of making the army self-supporting must be borne with the utmost patience. Any requests regarding welfare, which are contrary to this object, will be refused.’Footnote 2 Although economically constrained, Japan took policy in Southeast Asia to an extreme in supplying the region with virtually no goods and instructing its military to live off the land. In Thailand, however, it was desirable for Tokyo to appear to be paying for goods, because of the kingdom's alliance with Japan and future role as a nation state in the Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Thailand is often regarded as escaping lightly during the war and, compared to the rest of Southeast Asia, that is true. Nevertheless, it will be shown that Japanese exploitation was extreme and the privations inflicted on the Thai considerable. As well as paying the costs of being occupied, Thailand exported large quantities of food and other commodities to the Japanese but through an extreme form of clearing arrangements received mainly non-spendable paper credits in exchange, leaving the Thai people acutely short of most basic consumer goods.

The other main aim of the article is to use Thailand's financial experience of Japanese occupation to understand the unusual nature of the Thai economy in comparison to other Southeast Asian countries. Although Japan directed the Thai to print large quantities of baht to finance occupation and the acquisition of Thailand's resources, Thailand, in contrast to the usual Southeast Asian Co-Prosperity experience, avoided hyperinflation. The article argues that this was because of confidence in the currency, and so lowered inflation expectations, due to a continued use of baht not military scrip as in most of Southeast Asia; the structure of the Thai economy; and the behaviour of Thailand's rice-producing peasantry in hoarding baht.

The literature on Japanese Co-Prosperity finance in Thailand, and in Southeast Asia generally, is sparse. The work of Lebra (Reference Lebra1975) and of Yellen (Reference Yellen2019) hardly mentions finance. The financial implications of Thailand's incorporation into the Japanese Empire and how this influenced subsequent economic change in the kingdom remain to be addressed. We draw on Ingram's (Reference Ingram1971, pp. 63–5) and on Huff and Majima's (Reference Huff and Majima2013) work on financing Japanese occupation, but have a wider perspective, including Thai government deficits and Japanese methods of resource extraction. Swan's research adds significantly to an understanding of occupation finance but focuses on the negotiation process for an initial agreement and stops at 1942. In an incisive article, Reynolds (Reference Reynolds, Duus, Myers and Peattie1996, p. 257) passes briefly over finance, concluding with regard to Thai–Japanese financial arrangements that the Thai drove ‘as hard a bargain as they could’.

The present article relies on previously untapped Thai sources. These clarify, from a Thai perspective, the impact of Japanese finance. It has been claimed that during the war: ‘the Thais could keep track of their financial affairs thus allowing them to pursue active policies to remedy their economic and monetary problems brought on by the war . . . Thais could defend their interests vis-à-vis Japan's demands and could negotiate to ameliorate their situation ’ (Swan Reference Swan1989, p. 346). A more accurate assessment of Japanese policy reveals the contrary. Thailand had much less control over its finances than previously suggested. Although the Thai may have got the best deal obtainable, it was an extraordinarily poor one. Japanese financial demands were extreme and, although possibly subject to some negotiation, they were almost entirely met.

The article is structured in seven sections. The first examines the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in regard to Southeast Asia, Thailand's place in the sphere, and its anticipated benefits for Japan. Section II explains Japanese financial techniques in Thailand, while the third section shows how these enabled the economic exploitation of Thailand. The fourth section evaluates shortages and black markets in Thailand and Section V analyses why inflation, although high, did not skyrocket but remained relatively moderate despite wholesale money creation in response to Japanese demands. Section VI assesses Co-Prosperity aims in light of Thailand's wartime finance. A concluding, seventh, section briefly considers two major post-war legacies in Thailand of Japanese wartime finance, the resulting problems and their resolution.

I

The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere became an officially declared aim only in August 1940, a policy the next month and, on 2 July 1941, a Liaison Conference concluded that Japan must establish a sphere (Ike Reference Ike1967, pp. 77–90). In December 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, its existing mini-empire included only Korea, Taiwan and Manchukuo with the possible addition of some of China. Southeast Asia, under colonial rule apart from Thailand, would have to be made part of a Co-Prosperity Sphere through conquest. If this were successful, Japan, paralleling Germany's aims in Europe, could realize the economic benefits of domination of much of Asia. Southeast Asia's six countries – 1.7 million square miles, 141 million people (twice Japan's population) and economies complementary to Japan's – would complete an East Asian economic unit big enough to become, with appropriate modifications, essentially self-sufficient, effectively insulating Japan from the international economy (Butow Reference Butow1961, p. 203; Milward Reference Milward1970, pp. 146, 148).

During the 1930s, Japan had relentlessly sought to export to Southeast Asian markets, and had penetrated them until halted by the protectionism of the colonial powers. The envisaged Co-Prosperity Sphere would overcome export restrictions, and so also balance of payments problems, through an assured market for Japanese manufactured goods and, at the same time, provide raw materials for Japanese industry. After the formation of a Co-Prosperity Sphere, Japan's 1930s balance of payments problem would evaporate because the establishment of a yen bloc throughout the sphere would allow payment in yen rather than in foreign exchange for raw materials needed for industrialization. Yen could always be printed if required, but that would probably be unnecessary: the food- and raw-material-producing constituents of a Japanese empire would need yen to pay for manufactured imports from Japan as the empire's industrial centre (Matsuoka Reference Matsuoka1939, pp. 1–5; Arita Reference Arita1941, pp. 10–15; Yamada Reference Yamada1941, pp. 876–81; Yasuba Reference Yasuba1996, pp. 544, 555–7). Any mechanism that forced Japan to reduce its debts in East Asia would be eliminated. Tokyo would be established, as a Thai government minister observed, ‘as the monetary centre of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’.Footnote 3

When the war in Europe and early German victories isolated European colonies in Southeast Asia, Japanese leaders identified an unrepeatable opportunity to take control of the region: Southeast Asian ‘natural resources waited for Japanese picking like “fresh rice cakes off a shelf”’ (Drea Reference Drea2009, p. 209; and see Ike Reference Ike1967, pp. xix, 134, 202, 238). Above all, Japan, at the start of the Pacific War with, at most, two years’ supply of oil, needed control of Indonesia's oil fields and refineries in Sumatra and Borneo. Because Japan relied on imports even to feed itself, the Japanese also required rice from Thailand and Indochina. Southeast Asian rice would feed the home population and troops overseas. Critically for the war effort, Southeast Asian rice would allow Korea's economy to shift from agriculture to military production. Rubber, tin and sugar, Southeast Asia's other main exports, were not essential because Japan already had ample supplies of these commodities (Huff Reference Huff2020).

Within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Southeast Asia was different, and within Southeast Asia Thailand was yet more different. By May 1942, when Japanese forces controlled virtually all of Southeast Asia, Japan had already undertaken to divide Southeast Asia, militarily and politically, into Areas A and B.Footnote 4 These reflected the particular uses Japan had for different countries. Usage depended on the pre-war political status of countries, their possibilities for different administrative modes and alliances, and their geographical and resource advantages. Burma and Malaya, colonies of Britain, Indonesia, governed by the Netherlands, and the Philippines, a United States colony, were all put under the military rule imposed on Area A. This was accompanied by substantial occupying forces and the eradication of European institutions such as businesses and banks.

Thailand and Indochina comprised Area B. Both countries, allied with Japan, retained their existing governments, businesses and banks. However, enemy assets, including European banks, were seized. Tokyo made clear in its Outline of Policy Toward Thailand Japan's immediate plans for Thailand's complete integration into the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (Swan Reference Swan2009, pp. 249–53). The same was intended for Indochina but, despite this and other features in common, Thailand differed in a fundamental respect from Indochina: Indochina was allied with Japan through a Vichy French colonial government, while historically Thailand, through a ‘flexible “bamboo” diplomacy … based on a realistic view of the world’, had preserved national independence (Reynolds Reference Reynolds1994, p. 236). The Japanese left the Thai government to manage the day-to-day running of the country, creating the appearance of Thai control of the country's government.

That arrangement was convenient for the Japanese. It minimized strains on administrative and military resources, in short supply due to the vast area of the Pacific Japan had occupied and ongoing war. Thailand also realized benefits. For the Thai elite and government of Prime Minister Phibunsongkram (Phibun), it meant the retention of office and a degree of power. For ordinary Thai, despite unwelcome Japanese incursions, it minimized Japan's military presence, even in comparison to Indochina, where finally in March 1945 the Japanese took full control. Thailand, alone in Southeast Asia, largely avoided the Japanese excesses of imprisonment, torture and massacres, preserving a certain normality (Huff Reference Huff2020).

Economically and financially, Thailand also differed from the rest of Southeast Asia. It was unique in Southeast Asia in having a near country-wide economy of small, largely self-sufficient peasant land owners. Urbanization was low, with Bangkok the only sizeable city. The Thai economy had ‘an extremely broad subsistence base onto which the money economy has been grafted’ (Ingram Reference Ingram1971, p. 128; and see Yang Reference Yang1957, pp. 4–5; Reeve Reference Reeve1951, pp. 4–5). Some 80 per cent of peasants lived mainly in a self-sufficient economy (De Young Reference De Young1955, p. 193). Salient features of Thailand's rural economy were that agriculture engaged 89 per cent of people in 1937, and a similar proportion grew rice for their own use; 90 per cent or more of cultivated land was under rice; and 85 per cent of cultivated land was operated by owners.Footnote 5 Rice and fish were the main constituents of the Thai diet. Fish could be caught even in canals and waterholes, while most Thai farmers grew vegetables.

The rest of Southeast Asia contrasted markedly with the ability of the Thai economy to sustain itself in a time of crisis like the Pacific War and Japanese occupation. Because of this sustainability, as discussed below, Thai could hold currency rather than having to use it and bid up prices in times of scarcity. Malaya had substantial urbanization, specialized in the non-foods of rubber and tin and imported two-thirds of its rice consumption. Java also normally relied on imported rice and other foods, as did most of Indonesia's Outer Islands and also the Philippines. During the war, famine led to the death of some 2.4 million Javanese, while the Philippines had small local famines and sustained Manilla's population only through large private relief efforts (Weston Reference Weston1945, p. 24; van der Eng Reference Van Der Eng2008, p. 38).

Lower Burma and Vietnam, because of Cochinchina in the south, were major rice exporters, and so the closest comparators to the Thai economy. The two countries showed marked dissimilarities, however. Vietnam was in a much different position than Thailand, because in times of poor crops, Tokin and northern Annam relied critically on rice imports from the south. Central and northern Burma depended on rice from the south while it relied on central Burma for cooking oil, vegetables, gram (bean flour) as well as a number of other foods and clothing.Footnote 6 During the war, when a lack of transport and Japanese policies of intra-country autarky prevented exchange within Burma, the majority of those in Rangoon, and probably also in surrounding Lower Burma, became malnourished.Footnote 7

Thailand and Indochina were the only countries to retain their pre-war currencies during Japanese occupation. Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, the Japanese used military scrip, printed as needed, to finance occupation. The scrip, derided by Southeast Asians as ‘banana money’ (Malaya and Indonesia) or ‘Mickey Mouse money’ (Philippines), was cheaply produced. Its print quality was, the Japanese acknowledged, ‘appalling’ and deteriorated as the war continued.Footnote 8 To counter civilian resistance to scrip, the Japanese strictly enforced circulation on pain of severe punishment, even of death, for any use of substitutes. By contrast, in Thailand, the continuity of currency joined with the continuance of a pre-war, apparently independent, government in conveying to most Thai an air of normalcy, especially outside Bangkok, where occupation touched relatively lightly.

II

Occupation gave Japan the choice of how to exploit Thailand most beneficially and left the Thai with the problem of how best to accommodate exploitation financially.Footnote 9 This section considers possible Japanese exploitation strategies; the next how the Thai accommodated Japanese demands. Non-market exploitation includes looting or plunder, forced labour and the occupier convincing the local population to work for them and, if at below-market wages, in effect be taxed. Japan had to balance these non-market options against its three main longer-term objectives in Thailand. One was to obtain rice to feed the Japanese population at home and the military in occupied Asia. A second involved Thailand's geography in Southeast Asia: the kingdom, bordering on Indochina, Burma and Malaya, was at the centre of the most direct east–west land route across the region. Japan – weak economically, with a relatively small population, overstretched in Southeast Asia and bogged down in China – needed to secure, at low administrative and manpower cost, Thailand's strategic location for military operations. Third, the war would be only temporary and Japan intended to integrate Thailand into the Japanese sphere.

Plunder had little attraction as an exploitation strategy because most rice was exported soon after milling and not stored in Thailand and because the country had virtually no industry except rice mills, which had to be left in place for Japan to secure the grain regularly. The Nazis opted for a similar strategy in Belgium: looting could provide immediate supplies but might tell against long-term deliveries (Oosterlinck and White Reference Oosterlinck, White, Scherner and White2016, p. 180). Nor, unlike for Nazi Germany in occupied France and Belgium, was there any industrial plant and equipment in Thailand for Japan to carry home or significant financial resources to extract (Occhino et al. Reference Occhino, Oosterlinck and White2008; Oosterlinck and White Reference Oosterlinck, White, Scherner and White2016).

Forced labour or the deportation of workers to Japan were not attractive as means of exploitation. Over four-fifths of Thai grew rice; Thailand had almost no industrial workers or skilled labour. It would not, as Japan realized, have been a wise idea to upset Thailand's alliance with Japan and the Thai people by pressuring or requiring work for the Japanese or systematically plundering the kingdom. Better to maintain outward harmony, allow the pre-war government to continue administering Thailand and secure Thai rice and the country's strategic position at slight cost in troops and administrative personnel. As important, the Japanese had a low opinion of Southeast Asians as workers and the possibility of training them; because of this – in contrast to forced labour and possible transportation to Germany in Poland, France and Belgium under the Reich – they took almost no one from anywhere in Southeast Asia to work in Japan, and in Thailand recruited at most a few voluntary workers (Bräu Reference Bräu, Scherner and White2016, pp. 436–7; Oosterlinck and White Reference Oosterlinck, White, Scherner and White2016, pp. 178, 189). Some residents of Thailand were co-opted as labour for the infamous Thailand–Burma railway, but these were ethnic Chinese recruited by the Bangkok Chinese Chamber of Commerce, not the Thai government (Bualek Reference Bualek1997, pp. 202–6).

Finance had to be Japan's principal exploitation strategy. Extraction can be affected through three financial mechanisms: levying occupation costs that require the occupied to meet the expenses of being occupied; devaluing the currency of the occupied against the occupier's; and by establishing a form of clearing arrangement to pay for exports to the occupying country. In Thailand, this last was the most important but, like the Nazis in Europe, the Japanese used all three tools (Milward Reference Milward1977, pp. 137–9; Oosterlinck Reference Oosterlinck, Bucheim and Boldorf2012, pp. 95–7). Occupation costs are standard practice and, although open-ended, in the case of Thailand these were relatively small in relation to other exploitation, since the Thai government remained in place and Japan, allied with Thailand, stationed only a few troops there.

The three financial mechanisms operated against a backdrop of an overarching long-term Japanese policy to integrate Thailand financially into the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Successful political and economic integration depended partly on appearing to preserve Thailand's sovereignty, a symbol of which was the baht, and promoting stability in the kingdom. Continued use of the baht was advantageous for Japan so long as Japan could accomplish two things: determine how much money was printed for Japanese use; and ensure that these printed notes be given to Japan without, or almost without, cost to ‘buy’ Thai goods. Japan realized both objectives.

To achieve its resource acquisition goals in Thailand Japan negotiated two bilateral agreements. Both were more subtle than the device used elsewhere in Southeast Asia of issuing military scrip but amounted to virtually the same thing. Nazi Germany employed similar devices to Japan's in Thailand of devaluing the currencies of satellite countries and establishing clearing accounts. In the latter, as set up by Nazi Germany with satellite countries, each country paid its own exporters and entered credits for the payment in its account. The arrangement made it easy for Germany to overvalue its currency, assign artificially low prices to other countries’ exports and not come even close to matching flows of goods from occupied countries with flows from Germany (Oosterlinck Reference Oosterlinck2010, p. 212). Similarly, Denmark shipped ‘vast quantities’ of agricultural commodities to Germany ‘paid for with worthless paper claims’ estimated at 2,000 million Danish kroner (Bloc and Hoselitz Reference Bloc and Hoselitz1944, p. 40). Even noting inadequate Nazi payment for goods, the Japanese bilateral trading agreement was at the extreme end of Germany's because, as discussed below, it required that Japan send almost no goods to Thailand and that the Thai print currency which Japan could use to buy Thai goods. The balancing item against the Thai currency was merely paper credits, not immediately spendable and possibly spendable only after the war and in the event of a Japanese victory.

The first Japanese–Thai agreement, for baht–yen parity on 22 April 1942, devalued the Thai baht from 155.7 yen to 100 yen per 100 baht, allowing Japan to acquire Thai goods at about two-thirds of their previous cost.Footnote 10 Echoing Japan's vision of an integrated wartime empire, Thai and Japanese newspapers reported that baht–yen parity would improve Thailand's status as a trading centre and tighten its relationship with others in the yen bloc, since Japan pegged all Co-Prosperity currencies at parity with the yen (Swan Reference Swan1989, p. 333).

The second agreement, that the costs of occupation and trade would be paid through a clearing arrangement, required that Thailand print notes for Japanese use in exchange for ‘special’ yen. The yen were ‘special’ because they could be spent only with Japanese permission, which was, as explained below, nearly impossible to obtain.Footnote 11 Thailand had effectively no say in how much currency was to be printed nor how, if at all, special yen could be spent on goods from Japan or elsewhere in the Co-Prosperity Sphere. In effect, Thailand created whatever purchasing power Japan required offset against all but unusable special yen. The restrictions on special yen undermine the claim that ‘Thailand's monetary system remained in Thai hands’ (Swan Reference Swan1989, p. 346).

Prior to the adoption of the bilateral agreements, Japan had borrowed heavily from Thailand, including a loan of 80 million yen (which, being before devaluation, was still 50 million baht) to Japan's Yokohama Specie Bank. The Bank was to repay as much of the loan as possible in baht by 1 July 1942, the remaining balance to be settled in gold (Swan Reference Swan1996, p. 140). The Japanese were unhappy about debts to Thailand, especially the gold repayments, and pushed for a policy change. This came first through the baht–yen parity agreement and then, in May 1942, the arrangement that Japan could pay for Thai goods, as well as repay loans, in special yen instead of gold (Swan Reference Swan1989, pp. 325, 338).

The process of giving Japan baht to obtain Thai goods and services was as follows. The Yokohama Specie Bank would credit the accounts of the Bank of Thailand with special yen. The Bank then had to print the equivalent quantity of baht for the Japanese to spend on Thai goods. Because the baht–yen parity agreement prohibited any adjustment to the exchange rate, the Thai government could not revalue the baht and reduce money creation.Footnote 12

To use special yen, private exporters were required to obtain an ‘export bill’ from the Yokohama Specie Bank in Japan, which would send the bill to its Bangkok branch for collection. Once goods were sold and the exporter received revenue in baht, he still had to settle the export bill through the Bangkok office of the Yokohama Specie Bank. The Thai Ministry of Finance stated that

exportation of goods from Japan without export bills [was] prohibited by the Foreign Exchange Control Law of Japan, as it was prohibited in Thailand by the Ministry of Commerce, except the case when previous special permit [was] accorded. It [was] not only very difficult but also very troublesome to obtain such a permit.

The Thai government would have to obtain the permit to pay for imported goods from its special yen account, as these transactions were deemed an export of goods without an ordinary export bill.Footnote 13

Many Thai lodged complaints with the Ministry of Finance after Japanese companies refused to accept payment in yen credits, a common occurrence and indicative of Japanese merchants’ awareness of the worthlessness of special yen. In March 1943, for example, the Thai Ministry of Defence attempted to purchase ammunition and aeroplane parts with yen credits; however, the seller demanded settlement in baht and still refused special yen payment after a series of negotiations.Footnote 14 Similarly, in September 1943, the Ministry of Commerce tried to buy medical supplies from a Japanese company, Takeda Pharmaceutical, but it refused settlement in special yen.Footnote 15 Thailand, unable to use special yen, was handing its commodities to Japan but receiving nothing in exchange.

The special yen scheme was a powerful tool for resource extraction. It gave the Japanese purchasing power limited only by Thailand's physical capability to provide goods and services. After months of negotiation, Thai officials were able to persuade Japan periodically to convert 10 per cent of credits into gold to be held in Tokyo (Huff and Majima Reference Huff and Majima2013, p. 941). Even so, Thailand was at a strong disadvantage. The Japanese were essentially dictating Thai currency terms for their war effort and in exchange for baht giving pieces of paper, which could be regarded as IOUs eventually, if ever, to be paid.

In conjunction with the special yen agreement, Japan wanted a central bank in Thailand to handle special yen credits and, as stated in the Outline of Policy Toward Thailand, to ‘bring about a firm and organically connected monetary base with our Empire’ (Swan Reference Swan2009, p. 250). While before the war Thai officials had considered a central bank, its establishment was shelved because there was no immediate need for it (Muscat Reference Muscat1994, p. 27; Swan Reference Swan2009, pp. 217–18; Hossain Reference Hossain2015, p. 460). Japan proposed a Japanese-initiated and -operated central bank. However, Thai negotiators strongly objected to this and Thailand's government, under pressure, moved quickly to found the Bank of Thailand in 1942 with Prince Wiwattanachai (Vivadhanajaya) as the Bank's first director. Japan could now easily integrate Thailand into the yen bloc, and fund occupation and resource extraction. The Bank of Thailand was ‘the last piece in Japan's reorientation of Thailand away from the pre-war, British-centred economic order’ (Swan Reference Swan2009, p. 220).

III

To finance occupation in Thailand, Japan did not, unlike in militarily administered Malaya and Indonesia, have to try to juggle a mix of scrip, bonds, money and a plethora of taxes, levied even on hand carts, rickshaws, taxi dancers (women at public dances with whom men purchased a ticket to dance) and prostitutes. By leaving Thailand's government in place, Japan, as Nazi Germany did in France and Belgium, passed to the Thai the problem of how to finance occupation. A solution was difficult for the Thai government not just due to large financial demands but because it had limited scope to arrive at an optimal mix of taxation, bond issues and money creation. This section shows why Thailand's specialized, largely traditional economy had narrower options in complying with Japan's demands than occupied Europe's more developed economies had with Germany's.

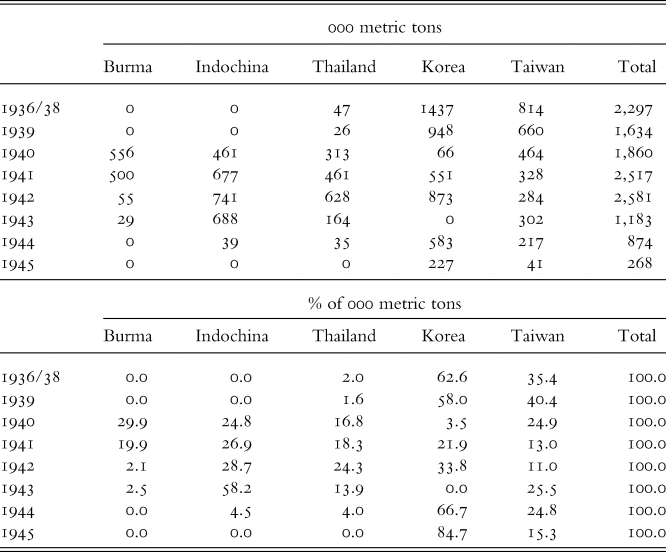

Thailand's government, moulded in outlook by the British advisors who directed pre-war finance and a colonial currency board model, was financially conservative. Accordingly, the Thai authorities, anxious to protect the baht, regarded taxation as optimal and were anxious to finance through it. Raising tax revenue was challenging, however. Between 1941 and 1945, Thailand's real GDP fell 14.4 per cent and per capita GDP 19.5 per cent, and trade, apart from exports to Japan and smuggling, dropped to almost nothing, severely shrinking the tax base (Table 1). Before 1942, import and export duties comprised almost a third of government revenues. The prohibition by the Japanese of trade except with Japan caused sharp drops in revenue from customs duties and taxation. Customs receipts, deflated by the retail price index, fell from 44.5 million baht in 1941 to 4.5 million baht in 1944, while over the same period tax revenue decreased from 76.1 million baht to 32.6 million baht.

Table 1. Thailand: GDP, money and inflation, 1941–50

Sources and notes: Prices: BT, Bank of Thailand, Economic and Financial Report, 1947, p. 8; 1948, p. 7; 1949, p. 9; 1950, p. 7. Note: for 1938, 1941, 1942 the figures are for the ‘whole year' while for 1943–57 they are from December of each year. Money: BT, Bank of Thailand, Economic and Financial Report, 1943, pp. 4, 9; 1944, p. 17; 1947, p. 11; 1948, p. 12; 1949, p. 15; 1950, p. 12. GDP: van der Eng (Reference Van Der Eng1994).

The government tried to compensate for wartime revenue losses by taxing the lower classes at home. It increased excise on mass consumption items like alcohol, opium and matches, and expanded the lottery. Fees were also increased for various governmental services, including postage, telegrams and trains. Taxes were levied on shops, hotels and financial institutions.

‘Savings cards’ (บัตรประหยัดทรัพย์) introduced by the government were essentially obligatory bonds, yielding little if any interest.Footnote 16 Every citizen was required to purchase a yearly savings card to the value normally paid in income tax. Interest on the savings cards was much lower than inflation, and so a means of taxation. According to officials, the cards were advantageous because they guaranteed revenues from even the poorest tax-paying citizen and ‘taught’ the public how to save money.Footnote 17 The cards did not, however, go far to finance occupation, as Thailand was overwhelmingly rural and Thai peasants did not pay much income tax in the first place.

A further, non-tax method was to sell government holdings in private companies.Footnote 18 However, like the government's many new duties, the sale of state assets fell far short of replacing income from import and export customs. Government revenue halved between 1941 and 1944, almost wholly due to the loss of customs and tax receipts.Footnote 19

Thailand's government, without recourse to the well-functioning financial markets like those in the Netherlands, France and Belgium, had, at best, narrow scope to sell bonds to banks or the public (Oosterlinck Reference Oosterlinck2010, p. 215; Reference Oosterlinck, Bucheim and Boldorf2012, p. 93). Thailand did not have a stock market and its main banks were European; these were permanently shut down by the Japanese. Local banks were small, with limited capacity to buy bonds, while Thai peasants, the great bulk of the population, had almost no contact with banks.

Marketing bonds as a patriotic duty failed in World War I America; the Thai experience was similar (Kang and Rockoff Reference Kang and Rockoff2015, pp. 46, 74). The state had some success with an issue of 30 million baht of gold bonds at 3 per cent interest, managing to sell roughly two-thirds of these to the public. However, the public purchased only 6.7 million baht of 18 million baht of ‘bonds for industrialization’ bearing 4.5 per cent interest. Thai citizens bought just 2.8 million baht of the 12 million baht of bonds for cooperatives at 4.5 per cent interest.Footnote 20

The Japanese closure of European banks did, however, facilitate the rise of local Thai commercial banking. Four new banks were founded, bringing to eight the total number of Thai commercial banks in 1945.Footnote 21 As early as 1943, the Bank of Thailand responded to the spread of banking with an Emergency Decree for the Control of Credit, which tried to encourage banks and insurance companies to hold government bonds (Silcock Reference Silcock and Silcock1967, p. 192). But that met with little interest from any of Thailand's banks. The main effect of additional banks was that by 1945 competition among them and earlier banks to offer credit on easy terms had considerably increased money supply, M1, adding to the problem of monetary expansion discussed below.Footnote 22

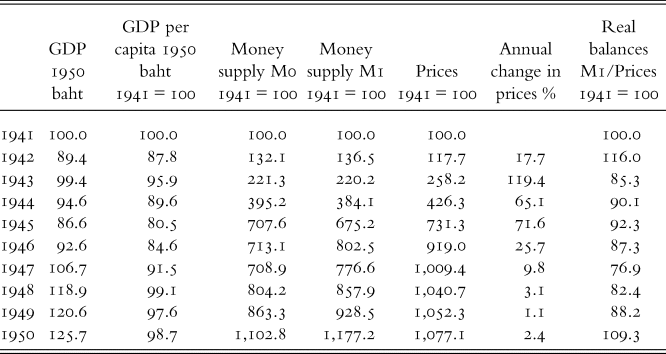

Almost every wartime government in occupied countries finances substantially through money creation. The Thai government, with such limited recourse to taxation and bond sales or scope for financial repression in Thailand's traditional economy, had little choice except to rely heavily on printing money. In 1942 and 1943, the government had settled budget deficits with treasury reserves. These, however, were quickly depleted and the Japanese demand for Thai baht had to be met. The only avenue left to the Thai government was money creation by selling non-interest-bearing bonds to the Bank of Thailand.Footnote 23 Money supply M0 increased over sevenfold between 1941 and 1945, from 297 million baht to 2,103 million baht, a rise of a little over 1,900 million baht. That almost exactly equalled the 1,800 million baht printed during occupation to provide special yen to the Japanese (1,500 million baht) and to cover the budget deficit (300 million baht) (Table 2).

Table 2. Currency notes printed by purpose, 1942–5 (million baht)

Source: Thailand (1951), Report of the Financial Adviser, p. 54.

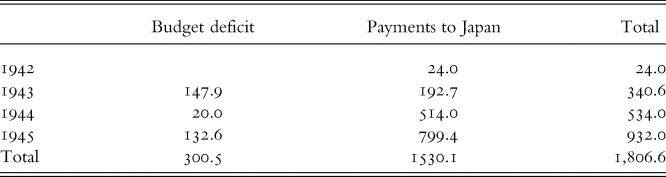

A principal Japanese use of the 1,500 million baht printed under the special yen agreement was to obtain Thai rice. Until 1940, Japan had relied on Korea and Taiwan for rice but, as part of the plan for a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Korean labour was shifted from agriculture to industry (Table 3). Thailand also supplied Japan with other commodities, notably timber needed to construct housing for Japanese troops and defence installations.

Beginning in 1944, Thai rice exports to Japan dropped sharply because the Allies decimated the Japanese merchant marine, leaving Japan desperately short of shipping. From then onwards, as the war continued and goods became scarcer and more expensive, the Japanese need for baht for military purposes escalated. During the last six months of the occupation, Japanese army expenditure demands, and with this occupation costs, rose from 48.8 million baht per month in 1944 to some 100 million baht.Footnote 24

Records of government spending in the Statistical Yearbooks detail revenue and expenditure for ministries and other governmental bodies, while the Bank of Thailand annual reports give the big picture. Between 1941 and 1945, expenditure exceeded revenue by over 350 million baht, including the 80 million baht loaned to Japan.Footnote 25 The largest contributor to the deficit was extraordinary expenditure for national defence. In 1943, it accounted for 56 million of 70 million baht of extraordinary budget expenditure and in 1944 for 73 million of 164 million baht. During the eight months of 1945 before the Japanese surrender, Thailand spent a staggering 99 million of 112 million baht of extraordinary expenditure on ‘national defence’. Since Ministry of Defence expenditure on the army, navy and air force was already included in the ‘ordinary expenses’ budget, ‘national defence’ was most likely for air raid protection, compensation to war victims and payments to Thai military forces.Footnote 26

Printing large quantities of money led to other problems besides inflation. Prior to the war, the Thai government used a firm in England, Thomas de La Rue, to print notes. After the Japanese invasion, this business was terminated and the Japanese firm Mitsui Bussan printed Thailand's notes. When commercial shipping between Japan and Thailand broke down, Thailand relied on notes printed in Indonesia and locally at either the cartography departments of the Royal Thai Army or the Royal Thai Navy. Although notes printed during the war were virtually identical to pre-war currency, they were more easily forged. The Bank of Thailand was still battling forgery in the late 1940s.Footnote 27

Illegal tender printed by the Japanese was smuggled across Thailand's southern and western border, adding another caveat to the contention that the Thai controlled their own finances. In 1941, for instance, the Japanese forces printed 5 baht and 10 baht notes, which the Thai government called the ‘Japanese army dollar scrip (ธนบัตรดอลลาร์ของทหารญี่ปุ่น)’. These notes were common in the south, especially Songkhla province, and spread to Malaya, causing the Thai government to loan Thai baht to Japanese troops to stem the usage of illegal notes. The printing of army dollar scrip ceased in 1942 after requests from Thai officials, but the Japanese army continued to circulate its scrip in many southern provinces, including Phuket.Footnote 28

The balance of trade between Thailand and Japan measures economic exploitation (Table 4). The exploitation of Thailand, defined as the imbalance of trade when the Thai were prohibited from trade except with Japan, was greater than for any other Southeast Asian country except Indochina, also a Japanese ally. Small trade surpluses for Thailand in the later war years are partly explained by sharp falls in rice sent to Japan, but probably more by Japan's shipment of goods for the military, since import statistics show the receipt of few consumer or capital goods. The physical quantities of goods Thailand received are even less than suggested by the yen data in Table 4 due to high Japanese wartime inflation. Thai surpluses are, furthermore, understated because of the enforced devaluations of the baht.

Table 4. Southeast Asia: trade balance with Japan, 1941–5 (000 current yen)

Source: Japan, Ministry of Finance (1941–51). Nihon gaikoku bōeki nenpyō [Annual return of the foreign trade of Japan], annual series, 1937–1944–48. Tokyo: variously published by Ministry of Finance, Cabinet Printing Office, Finance Association of the Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Printing.

IV

High inflation due to finance chiefly through printing money and the paucity of goods sent by Japan gave rise to black markets. Urban inhabitants with relatively fixed money incomes were disproportionately disadvantaged. Privation was especially serious for Bangkok's poor, since money wages lagged well behind prices and these people did not grow rice or have self-sufficiency in basic goods.

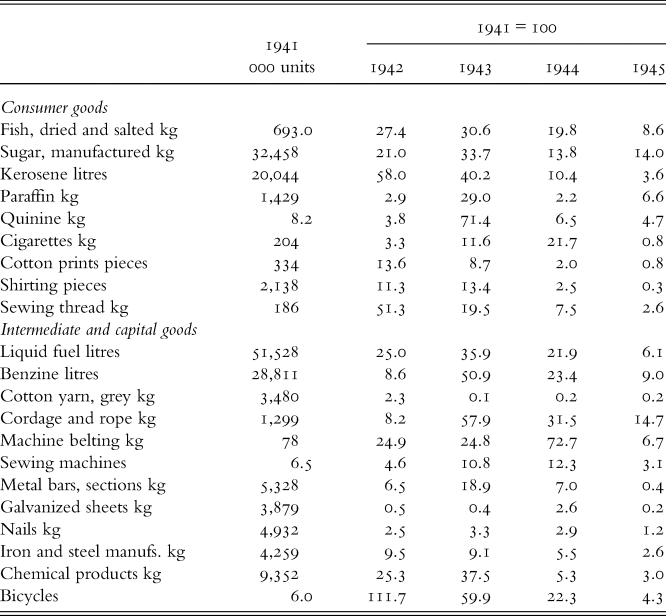

The best price data available are Bank of Thailand figures. These show that between 1941 and 1945, prices increased a little over sevenfold. Prices had their greatest yearly change from 1942 to 1943 as shortages became apparent, but continued to rise swiftly for the remainder of the war (Table 1). Because trade, except exports to Japan, was prohibited, Thailand, apart from stocks existing at the time of occupation and a few items obtained by smuggling, depended almost entirely on whatever goods the Japanese were willing to send. Japan never supplied much to Thailand, and by 1944 and 1945 almost nothing. Thailand manufactured few of its own consumer goods, and was no more than a third self-sufficient in textiles, the most important consumer item behind rice. The pre-war dependence on imports of most basic consumer goods and medicines was even greater than for textiles.

Already in November 1941, Japanese policy, as noted in the Introduction, was to not supply consumer goods to Southeast Asia. Thailand, despite its alliance with Japan, was no exception. By 1944, import volume of almost all basic goods ranged from between 2 and 20 per cent of 1941 levels and typically dropped much further in 1945 (Table 5). Due to declines in imports of consumer goods, those in urban areas, especially Bangkok, faced sharp cuts in living standards. Imports of manufactured materials and capital goods also dropped drastically, effectively preventing Thailand from using whatever manufacturing capacity it had to substitute local production for pre-war imports.

Table 5. Thailand: import volume of consumer and capital goods, 1941–5

Notes: Cordage and rope includes coir and Manila hemp. Nails include wire nails and other nails. Shirting includes white, grey, dyed and Turkey red.

Source: Thailand (c. 1947), Annual Statements of the Foreign Trade and Navigation of the Kingdom of Thailand 1942–1945, Bangkok: Department of His Majesty's Customs, pp. 1–53.

Alternative indexes of prices in wartime Thailand are quite similar to the official data used here. Nevertheless, a black market in some goods indicates significant hidden inflation, especially in Bangkok where middle-class Thai congregated and tastes and consumption patterns were more varied that elsewhere in the kingdom. However, even in 1947 just 6.2 per cent of Thai lived in towns of 20,000 or more. Official and other data fail to capture urban inflation because the index was weighted in favour of rice as the main item of consumption and the standard by which all prices were measured. That was reasonable, since even in pre-war Bangkok, as observed of nearly all its civil servants: ‘Their wants were few. They needed little in the way of clothing, and practically nothing in the way of fuel. Rents were very low. Their main food was rice plus a few vegetables and fish’ (Reeve Reference Reeve1951, p. 67).

Thailand's rice-specialized economy and an overwhelmingly rural, largely self-sufficient population of farmers helped to limit inflation and so also Thailand's black market. The Thai experience contrasted with the reliance on food imports in World War II countries like Belgium, Greece, the Netherlands and Poland. In these countries, wants were more complex than those of the Thai and, moreover, acute food scarcities developed, fuelling acute hunger and rampant black markets (Hionidou Reference Hionidou2006; Bräu Reference Bräu, Scherner and White2016, pp. 437–8).

The Thai experience also differed sharply from the Southeast Asian countries – Malaya, Indonesia, the Philippines, Upper Burma as well as Lower Burma for all but rice, and northern Vietnam – dependent on imported food. In these countries, as rice became ever scarcer, the economies moved inexorably towards hyperinflation and black markets flourished apace. People in Malaya came to think of the black market as normal, a way of life, and ‘when the stage arrived at which the public was compelled to pay black-market prices for such things as bus-tickets, railway-tickets, cinema-tickets, cloth-coupons, and even newspapers, the situation was beyond redemption’ (Chin Reference Chin1946, p. 37).

Thailand never came close to such disruption but the incorporation in available indexes of true prices for rationed and price-controlled goods and as well as luxuries favoured by Bangkok's middle class would reveal higher than reported inflation. By 1943 in Bangkok and its suburb of Thonburi, ration coupons were issued for lard, soap, sugar, fuels, matches and even rice (Numnonda Reference Numnonda1977, p. 93). Thai claimed that textiles and certain foodstuffs such as meat were constantly sold from the back room of shops at above regulated prices. In Bangkok, ‘no one would sell their commodities without huge profits notwithstanding the price control orders’ (Numnonda Reference Numnonda1977, p. 94 and see pp. 94–5). Thailand's most lucrative black market was, however, in rice smuggled to Malaya and Indonesia. Wartime rice smuggling to food-deficit Southeast Asia was instrumental in creating in Thailand a new class of ‘fabulously wealthy rice hoarders and smugglers’ (Yang Reference Yang1957, p. 35).

V

This section addresses two main aspects of inflation during the war. The first part considers government policies to try to check inflation, and shows that these did little, if anything, to restrain rapid price rises. Why then did inflation in Thailand not take off as elsewhere in Southeast Asia, with prices rising not too far adrift, even trying to factor in hidden inflation, money supply increase? Possible explanations for this comprise the section's other main subject.

The wartime Thai administration was acutely aware of the detrimental effects of inflation, and did its best to limit them. Thai administrators lacked control over monetary expansion, the root cause of high inflation, since the Japanese dictated monetary policy. Nevertheless, the Thai government instituted three main policies to try to curb inflation and, crucially, prevent it from turning into hyperinflation.

One set of policies, to restrict private spending, has already been discussed in regard to campaigns for the purchase of government bonds and savings cards. Additionally, the government tried to regulate business and extract funds through heavily taxing land and houses. None of these measures, given Thailand's largely rural and traditional economy, had much effect.

A second set of policies, to increase the available supply of consumer products, was a non-starter. Even under peacetime conditions an increase in goods to match wartime money supply expansion was impossible. During the war, even a moderate addition to the availability of goods was out of reach, because Japan sent almost nothing to Thailand and because the country lacked the raw materials, funds, equipment and human capital to manufacture enough goods to make up for more than a fraction of pre-war imports.

The third group of policies, deficit reduction and restrictions on private spending, was where the Thai government might have had some influence. Government efforts were, however, largely unsuccessful. Measures to cut the budget deficit involved both revenue increase and spending reductions. The failure of new taxation in raising much additional revenue has already been discussed. A principal strategy to decrease expenditure was to discharge or place officials on unpaid leave, refrain from any additions to staff and hold civil service wages at 1942 levels. This drastically cut real wages and left a legacy of endemic corruption because civil servants sought to protect their living standards through bribes and because, after 1945, parity with pre-war wages was never regained (Warr and Nidhiprabha Reference WARR and Nidhiprabha1996, pp. 23–6).

Thailand's inflation, both in its magnitude and relationship to money supply increase, sharply contrasts with the usual wartime Southeast Asian inflationary experience. Printing money as a means of finance relies on the public being willing to hold currency issued by the government. That, in turn, depends partly on avoiding high inflation and public expectations of future changes in inflation. If prices continuously increase and are expected to accelerate, people demand less money because its real value, or purchasing power, falls and is anticipated to fall yet faster. The anticipated response to high inflation is for people to seek to spend money as quickly as possible to avoid its further loss of value and obtain in exchange as large a quantity of goods or tangible assets as possible. As money's real value falls, governments have to print more of it to buy the same quantity of goods. A greater quantity of money, depending on expectations about its future value, rapidly pushes up prices and so also the quickness of spending money, or its velocity of circulation. If this happens, inflation accelerates more rapidly than money supply, leading, before long, to skyrocketing prices and in time to hyperinflation.

Unlike most of Southeast Asia, in Thailand the ratio of official prices at the end of occupation to prices at the beginning (7.3) was almost identical to the same temporal increases in money supply, M0 (7.1) and M1 (6.8). In other words, despite high inflation, with prices rising by larger amounts every year after 1941, the demand for money held up reasonably well. Because the rise in official prices nearly matched increases in money supply, real balances (the nominal value of money divided by the price level and so adjusted for inflation) were only somewhat less in 1944 and 1945 than in 1941. Although official price data clearly understate true inflation, it is also apparent that the Thai continued to demand money. Changes in its velocity did not lead to rapidly accelerating inflation and hyperinflation was avoided. The south of Indochina may have been, along with Thailand, an exception to Southeast Asian inflationary experience, but, unlike Thailand, southern Vietnam specialized in producing rice and the north was desperately short of it, suffering a million deaths from famine. The absence of price data for different parts of Vietnam precludes reliable comparison. Burma, the other main Southeast Asian rice producer, was war-ravaged and that ensured runaway inflation. Contrasts with Thailand elsewhere in Southeast Asia were clear. Prices in Indonesia rose three times as fast as money supply, while by 1945 prices in Malaya and the Philippines, as in Burma, were large multiples of their 1942 levels and had far outdistanced monetary expansion (Table 6).

Table 6. Southeast Asia: inflation and money supply, 1942–5

Source: Huff and Majima (Reference Huff and Majima2013), p. 953.

Why in Thailand, despite swift wartime monetary expansion, did prices at least keep in touch with money? Why did the Thai go on demanding money when its value was being comprehensively debauched? These questions can be explained through a combination of five reasons.

One, a transactional motive to hold money, was true of scrip, but the other four reasons all emphasize Thailand's particular World War II circumstances. In Thailand, as elsewhere in Southeast Asia, there were strong transactional motives for holding money. Wages were paid in baht and goods bought with them. Everyone needed the official money to pay taxes and for any market transactions.

The other four reasons are particular to Thailand. One depends on expectations, and can be examined using the quantity theory of money:

where M is the nominal money supply, P the price level at which goods and services are traded and Y is real national income. In this Cambridge formulation of the quantity theory, the community holds real money balances (M/P) in some proportion, k, of real income. The variable k (and its reciprocal 1/k, the velocity of circulation of money) are regarded as fairly constant. If so, kY on the right-hand side of the equation remains approximately constant, and the relationship between money supply, M, and prices, P, will be more or less proportional, as in wartime Thailand.

The variable k, and so circulation velocity, depends on current inflation and, crucially, also on inflation expectations. If prices are expected to accelerate at ever-increasing rates. people seek to rid themselves of money before its real value erodes even more quickly than it currently is. Eventually, printing more currency with no corresponding increase in goods available will cause people to lose confidence in the value of money; circulation velocity takes off and multiplies far more rapidly than money supply. That occurred in occupied countries forced to use scrip, since expectations of inflation, and so the value of Japanese money, depended on a victorious Japan. In Malaya, ‘Every time there was an Axis defeat, particularly Japanese defeats, prices of goods jumped up. Every Allied victory … and every visit of B-29s over Malaya, caused spurts of prices in foodstuffs. Saipan, Iwojima, Manila, Rangoon, and Okinawa were inflation spring-boards’ (Onn Reference Onn1946, p. 45). By contrast, in Thailand a firm knowledge that, whatever the war's outcome, the baht would remain the recognized currency probably steadied expectations and so helped to keep k in money's quantity theory relatively stable.

Second, substitute currencies were not available. Nor was there the same impetus towards substitution as in countries where the Japanese forced the use of scrip through punitive sanctions. In contrast to these countries with clandestine trading in pre-war currencies, the baht had always been the official money. Nor in Thailand was barter a viable currency substitute. Widespread barter requires some commodity or item to have the ‘moneyness’ qualities of being readily accepted as a means of payment, divisibility and ability to serve as a store of value. Rice, historically a barter currency in Southeast Asia, had the divisibility and store of value characteristics (Huff Reference Huff1989). But for Thailand, unlike most of the rest of Southeast Asia, rice failed on grounds of acceptability, since most Thai already grew rice.

Third, the wartime issue of baht by Thai authorities and Thailand's continuity of government bolstered confidence in the baht and so also its role as a store of value. There was no possibility that after the war the baht would be repudiated as the country's legal currency, something the Allies constantly told Southeast Asians would happen with military scrip. The Bank of England's governor, Sir Otto Niemeyer, telegraphed that: ‘[although we] have to redeem Japanese occupation currency most important that the impression should be created that we do not (repeat not) contemplate such redemption’.Footnote 29 In fact, the British and Americans did not redeem scrip after the war, as local populations likely anticipated.

A fourth explanation for a continued demand for money lies in Thailand's particular economic structure. Keynes (Reference Keynes1971, p. 66) pointed out that in agricultural countries because of peasant hoarding behaviour

inflation, especially in its early stages, does not raise prices proportionately, because when, as the result of a certain rise in the price of agricultural products, more money flows into the pockets of peasants it tends to stick there; deeming themselves that much richer, the peasants increase the proportion of their receipts that they hold.

The observation of Thailand's World War II Financial Advisor confirmed such behaviour: by the end of the war only 20 or 25 per cent of notes in circulation were in Bangkok; ‘The rest are in the provinces, where they largely disappear into farmers’ hoards: and the demand of the provinces for fresh supplies of notes is a never ceasing one.’Footnote 30 Further confirmation can be found during the 1949–51 inflation. Despite a large increase in money supply, prices did not rise to any comparable extent. Rather, ‘a large volume of notes were simply hoarded, mainly by up-country producers’ (Wiwattanachai 1961, p. 268).Footnote 31

This behaviour of the Thai peasantry may not fully be explained by money illusion (mistaking nominal for real values); it had a clear rationale. Peasant wartime demand for money was underpinned by the reality of limited spending opportunities due to the paucity of goods from Japan, little local production and the logic of long-term expectations (Friedman Reference Friedman and Friedman1969, p. 66). Peasants surely realized that manufactured goods would become more abundant after the war and prices would fall dramatically, allowing more goods to be obtained for less money outlay than during the war. A largely self-sufficient rural economy limited the need for the great bulk of the population to chase goods at a time of escalating prices.

VI

This section evaluates the wider implications of Japanese wartime financial policy and what this foreshadowed about the future place of Thailand and other areas of Southeast Asia in a post-war Co-Prosperity Sphere. Japan's expectations for the gains from war in Southeast Asia – the realization of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere – went well beyond the use of financial arrangements to exploit Thailand. But, although only a component of a strategy for a Japanese-controlled Co-Prosperity Sphere, financial policies in Thailand revealed, perhaps as much as anything, the reality of Japan's vision of shared prosperity in a new Asian economic order.

After deciding on war to build an empire and create a Co-Prosperity Sphere, Japan engineered special yen as the way to finance exports from Thailand and its occupation. As well as being nearly as costless as scrip, this incorporation of Thailand into a yen area had other long-term advantages. The Japanese aim for all of Southeast Asia in regard to a yen bloc was that the economic ties of currency, like those of focusing Thailand's trade on Japan, would make it politically impossible to separate from Japan once the war was over, thus cementing an Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Japanese planners envisaged Thailand during the war and in a post-war Co-Prosperity Sphere as part of a Southeast Asian ‘colonial-like’ periphery specialized in primary commodity production. Thailand would become a major source of rice and also teak, rubber and tin for the Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Thai and others in Southeast Asia would, in turn, look to Japan, and possibly also Korea, as industrial centres supplying manufactured goods. Through control of a large area, of which Southeast Asia would form an integral part, Japan would effectively insulate itself from the world economy. During the war, however, for Thailand the reciprocity of a Co-Prosperity Sphere was conspicuously absent, as it was throughout Southeast Asia. Little was exported to the Thai people, leaving them short of basic goods and lacking the materials and capital equipment to produce substitutes.

Far from Thailand remaining in charge of its wartime finance, as has sometimes been suggested, control was ceded to Japan. Although alliance with Japan helped Thailand retain a measure of independence and avoid many of the worst aspects of occupation, within a month of occupation the kingdom surrendered control over its finances, and so a principal plank of state sovereignty. Thai officials did not have financial jurisdiction, except insofar as they were left to determine how best to try to meet Japan's demands. Japanese economic exploitation of Thailand was extreme and limited only in the latter years of occupation by Japan's shortage of shipping. ‘This was’, it was remarked soon after the war, ‘Co-Prosperity with a vengeance, Japan getting the prosperity and leaving Siam [Thailand] with only the co.’Footnote 32 Even so, the draconian financial arrangements imposed on Thailand and the shipment of Thai goods to the Japanese in exchange for non-usable paper credits has remained little understood.

It was unrealistic to expect that the Thai people, deprived of many goods, would believe the extensive Japanese propaganda of ‘Holy War’ and pan-Asian nationalism. Nor was Japan's official justification for expansion into Southeast Asia, namely as the way to liberate its peoples from Western domination, the determining Japanese reason for a Co-Prosperity Sphere and war to establish it. Rather, Japan aimed to replace one kind of (Western) imperialism with another and, if the years of Thailand's occupation are a guide, a more rapacious one.

VII

This article has shown that Japan's Co-Prosperity Sphere and its wartime financial techniques, which required Thailand to print baht on demand, left an enlarged money supply, shortages of almost all goods and a diminished gross national product. None of these things were particular to Thailand: they were common outcomes of the Co-Prosperity Sphere throughout Southeast Asia. After the Japanese surrender, however, Thailand traced its own course. This concluding section briefly examines the major economic problems of money supply and inflation inherited by post-war Thailand and how the Thai government dealt with them. The solutions became two of the main post-1945 aspects of Thailand's political economy: the heavy taxation of Thai rice producers through a multiple exchange rate system and the extremely conservative monetary policies adopted by the Bank of Thailand.

Japanese war finance left the Bank of Thailand with almost no reserves and with serious monetary overhang resulting from wartime money supply augmented by a continuing increase in 1946. Some of the pre-war currency reserves in London were released, after an urgent appeal to the British government, to try to plug the gap in consumer goods. Most of the reserves, however, went to the British Custodian to meet various claims arising from the war and had to be written off. Special yen, unlike German blocked marks which dated from the early 1930s, were a wartime phenomenon. While Germany began to unwind its mark obligations soon after 1945, those represented by special yen were incorporated in reparation negotiations (Dernburg Reference Dernburg1955). Japan finally agreed in 1956 to the amount represented by special yen but did not complete payments (US$260.2 million) until 1969.Footnote 33 That left early post-war Thailand with only a small amount of gold in the United States. There was also a little gold in Tokyo but it was not recovered from the Bank of Japan until 1949.Footnote 34

The Thai economy inherited considerable purchasing power due to the large, Japanese-engineered money supply, but at the same time a ‘crying dearth of consumption goods’.Footnote 35 Post-war inflationary potential was further augmented by three factors. One was the peasant hoarding of notes, even allowing for some automatic amortization of these through loss, mutilation and destruction. A second was considerable increases in money supply M1 as the several Thai banks started during the war competed with one another to offer credit on easy terms. Third, prospects of upwards changes in inflation were further strengthened by the sharp wartime drop in national income (Table 1). The loss of GDP cut into Thailand's ability to produce goods to meet pent-up wartime demand. Nevertheless, between 1945 and 1946, the official data show an upwards movement in prices of a comparatively modest 25.7 per cent, and a smaller increase in 1947 (Table 1). It should be pointed out, however, that many people considered that the reported 1946 figure for inflation was too low to be the true; if it was not, the Bank of Thailand did not disclose to the public what the true figure was.Footnote 36 The wider point is that by the late 1940s, inflation was reduced to quite low levels (Table 1).

Fortuitously, a financial legacy of the war apart from inherited inflation, the Bank of Thailand, afforded the institutional means to counter monetary overhang, subdue inflation and then keep it low (Table 1). That depended crucially not just on the institutional apparatus of the wartime founding of a central bank, but on its personnel and their policies. Leaders of the Bank, Prince Wiwattanachai and Puey Ungphakorn, frightened by wartime inflation and citing the German hyperinflation, adopted an approach as conservative as Thailand's British-influenced pre-war monetary policy (Warr and Nidhiprabha Reference WARR and Nidhiprabha1996, p. 27). Beginning in 1947, the Bank, not the Thai government, took control of the huge amounts of revenue from a multiple exchange system which taxed Thai rice producers heavily (Corden Reference Corden and Silcock1967). Taxation of rice producers, and for a time also post-war inflation, helped to drain away peasant purchasing power arising from the wartime hoarding of baht.

The Bank used its jurisdiction over the large amounts of revenue generated through the multiple exchange system and by its 1955 successor, a rice premium system, to build up currency reserves and avoid any but small budget deficits. Throughout the 1950s, deficits on the balance of payments current account were moderate and after 1954 were largely financed by official loans and grants (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 1959, pp. 231–2). Owing to the Bank's stewardship, Thailand took advantage of a strong balance of payments to quickly replenish currency reserves. By 1957, Thailand had established 100 per cent gold and foreign exchange backing for the baht.Footnote 37 Putting the economy on so stable a basis helped to lay the foundation for Thailand's subsequent economic ‘miracle’.

Phibun's post-World War II import substitution industrialization programme required substantially more funds than it earned in revenue, leaving the government to finance the difference. Under these circumstances, budget deficits could easily have arisen together with the need to print baht to finance them. The avoidance of deficits and their likely accompaniment of high inflation was achieved through transfers, by the Bank of Thailand, of multiple exchange rate revenue to the government budget (Muscat Reference Muscat1994, pp. 76–7). Along with the Bank of Thailand, other essential economic components of post-war financial stability were, of course, the continued large world demand for Thai rice and Thailand's economic base of peasant rice growers to tax. Here, once again, Thailand's particular economic structure helped to make the kingdom different.