1. Introduction

From time immemorial, medicinal plants have been used to control diseases and parasites of humans and animals (Athanasiadou et al., Reference Athanasiadou, Githiori and Kyriazakis2007; Thirumalai et al., Reference Thirumalai, Kelumalai, Senthilkumar and David2009). However, much of the evidence of the medicinal potencies of plants has been based on anecdotal observations and reports with no corroboration from experimental trials (Athanasiadou et al., Reference Athanasiadou, Githiori and Kyriazakis2007; McGaw & Eloff, Reference McGaw and Eloff2008). In some other cases, there has been a disparity between ethnoveterinary reports and results of experimental trials (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Bevilaqua, Maciel, Camurça-Vasconcelos, Morais, Monteiro, Farias, da Silva and Souza2006; Githiori et al., Reference Githiori, Höglund, Waller and Baker2004). This study was carried out to investigate efficacy of three plants against Taenia solium (porcine) cysticercosis in pigs.

T. solium is considered a foodborne parasite with the highest burden globally (Torgerson et al., Reference Torgerson, Devleesschauwer, Praet, Speybroeck, Willingham, Kasuga, Rokni, Zhou, Fèvre, Sripa, Gargouri, Fürst, Budke, Carabin, Kirk, Angulo, Havelaar and de Silva2015). It causes neurocysticercosis, the major cause of acquired epilepsy in endemic areas (Mwape et al., Reference Mwape, Phiri, Praet, Speybroeck, Muma, Dorny and Gabriël2013; Reference Mwape, Blocher, Wiefek, Schmidt, Dorny, Praet, Chiluba, Schmidt, Phiri, Winkler and Gabriël2015; Ndimubanzi et al., Reference Ndimubanzi, Carabin, Budke, Nguyen, Qian, Rainwater, Dickey, Reynolds and Stoner2010). As infected pork plays an important role in the transmission of the parasite, treatment of infected pigs is instrumental in breaking life cycle of the parasite. To that effect, two herbalists in Mbulu district in north-eastern Tanzania claimed to have a knowledge of plants available in their localities, which treat porcine cysticercosis. One herbalist recommended a plant known as “gwaway” in iraqw, the local vernacular; and another recommended a concoction of two plants, “titiwi” and “ma’ayangu”.

Hence, this experimental study was carried out to confirm the purported efficacy of the plants in treating T. solium cysticercosis in naturally infected pigs. We envisage that the findings of this study will prompt further research on other plants of ethnoveterinary importance in Tanzania and elsewhere.

2. Methods

2.1. Study area

The plants were sourced from Mbulu District (3.80°–4.50° S; 35.00°–36.00° E) in Manyara Region, north-eastern Tanzania, where T. solium infections have been reported to be endemic (Boa et al., Reference Boa, Bøgh, Kassuku and Nansen1995; Mwang’onde et al., Reference Mwang’onde, Chacha and Nkwengulila2018; Ngowi et al., Reference Ngowi, Kassuku, Maeda, Boa, Carabin and Willingham2004; Ngowi et al., Reference Ngowi, Kassuku, Carabin, Mlangwa, Mlozi, Mbilinyi and Willingham2010). Study animals were collected from Mbozi District, in south-western Tanzania. The trial was carried out at the Tanzania Livestock Research Institute (TALIRI), Southern Highlands Zone, at Uyole, Mbeya Region.

2.2. Preparation of plant extracts

Mature plants were uprooted, thoroughly washed, and the roots were chopped into small pieces which were then dried in a shade for about 10 days. Dried root pieces were ground into powder and was then stored in air-tight containers until use. For the purpose of botanical identification, branches with leaves and flower fluoresces were collected and sent to the Department of Forest Biology, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro.

2.3. Study animals

Slaughter-age pigs suspected to be infected with T. solium cysts were examined for presence of palpable lingual nodules as described by Gonzalez et al. (Reference Gonzalez, Cama, Gilman, Tsang, Pilcher, Chavera, Castro, Montenegro, Verastegui, Miranda and Bazalar1990) and Ngowi et al. (Reference Ngowi, Kassuku, Maeda, Boa, Carabin and Willingham2004) (Figure 1). After a pig was confirmed to be infected, a consent to sell the pigs was sought from the owner. Twenty-four pigs were eventually bought and were transported to TALIRI-Uyole, where they were kept for 2 weeks for acclimatization before the onset of treatment. The pigs were provided with a compounded pig feed two times a day, in the morning and in the evening. Water was provided ad libitum.

Figure 1. Flow of study units during the experimental trial.

2.4. Study design and treatment of animals

This study adopted a randomized controlled trial design, where the 24 infected pigs were randomly allocated to three groups (T1, T2, and T0) of eight animals each. Each group was housed in a separate pen. Eight grams of “gwaway” (mixed with small amount of feed) were provided to each pig in the T1 group, at days 0, 7, and 14. The same dosing regimen was used for pigs in the T2 group provided with a concoction of “titiwi” and “ma’ayangu” (4 g of each). T0 served as control.

2.5. Pig slaughter, pork inspection, and carcase dissection procedures

nce the onset of the trial, the pigs were slaughtered. Routine meat inspection was performed using general provisions and guidelines for pork inspection in Tanzania (Government of Tanzania, 1993).

After the pork inspection, the brain, tongue and heart with psoas, masseters (internal and external) and Triceps brachii muscles were extracted. Previous studies have indicated these organs and muscles groups to be predilection sites for T. solium cysts (Boa et al., Reference Boa, Kassuku, Willingham, Keyyu, Phiri and Nansen2002; Sciutto et al., Reference Sciutto, Martínez, Villalobos, Hernández, José, Beltrán, Rodarte, Flores, Bobadilla, Fragoso, Parkhouse, Harrison and Aluja1998). Cyst counting was done by slicing the extracted organs/muscle groups using fine cuts (<5 mm). Cysts were classified as viable or degenerated/calcified, according to Boa et al. (Reference Boa, Kassuku, Willingham, Keyyu, Phiri and Nansen2002).

2.6. Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by scientific committee of the Zonal Agricultural Research and Development Fund (ZARDEF) of the Southern Highlands Zone (Ref. No. SHZARDEF/LP/10/02). Animal welfare regulations as stipulated in the section 40 of the Tanzania’s Animal Welfare Act number 19 of 2008 were strictly complied with. Pig owners provided an informed verbal consent to allow their pigs to be examined, and decision to sell a pig relied solely on a farmer’s willingness to sell.

2.7. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA© (StataCorp, 2001. Stata Statistical Software, Release 12.0. Stata Corporation 2011, College Station, TX). A difference in cyst numbers between groups was tested for significance using a Kruskal–Wallis H test. Dunn’s test was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments. Level of significance was set at 5%.

3. Results

3.1. Botanical identification of the plants

“Gwaway” was identified as Sericocomopsis hildebrandtii under the family Amaranthaceae, whereas “Titiwi” and “Ma’ayangu” were identified as Carissa edulis and Ximenia americana under families Apocynaceae and Olacaceae, respectively. The plant names were checked with http://www.theplantlist.org (website accessed on November 25, 2020).

3.2. Clinical observations

No visible clinical adverse reactions were noted as the effect of the herbal materials. However, three pigs, one from the T2 group and two from the control group died during the course of the trial, but the deaths were confirmed to be caused by sources other than the effect of the herbal materials.

3.3. Pork inspection and carcase dissection

After inspection, the meat from all eight T1 pigs was judged to be clean and aesthetically acceptable to a consumer and all the carcases were therefore passed for human consumption, except for the brain of four pigs. In contrast, the inspector found all the carcases belonging to the T0 and T2 groups unfit for human consumption and were all condemned.

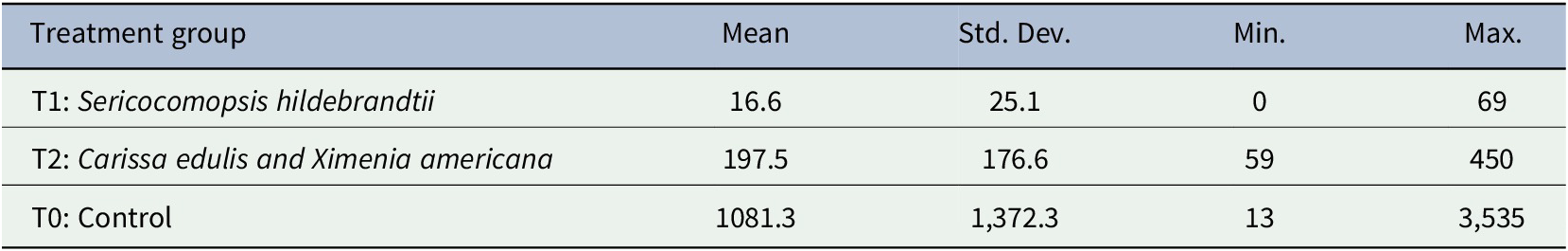

The recorded numbers of viable and calcified cysts in all slaughtered pigs are shown in Table 1. Overall, mean cyst numbers were highest in the control group (1,081 ± 1,372), and lowest in the T1 (S. hildebrandtii) group (16 ± 25) (Table 2). All cysts in T1 pigs were located solely in the brain tissues of four pigs and were all viable (Table 1). In T2 pigs, 92.3% of all cysts were viable while all cysts in the control group were viable. In both T2 and control groups, cysts were distributed in all dissected organs and muscle groups.

Table 1. Taenia solium cyst numbers in selected organs and muscle groups of 21 slaughtered pigs, 8 from T1 group treated with Sericocomopsis hildebrandtii, 6 of T2 treated with a concoction of Carissa edulis and Ximenia Americana, and 7 which served as a control.

Abbreviations: Calc., calcified/degenerated cysts; Via., viable cysts.

Table 2. Mean, minimum and maximum numbers of Taenia solium cysts of 21 slaughtered pigs, 8 from T1 group treated with Sericocomopsis hildebrandtii, 6 of T2 group treated with a concoction of Carissa edulis and Ximenia americana, and 7 pigs of a control group.

Abbreviations: Max, maximum number of cysts; Mean, mean number of cysts; Min, minimum number of cysts; n, number of examined pigs; Std. Dev., standard deviation of the mean.

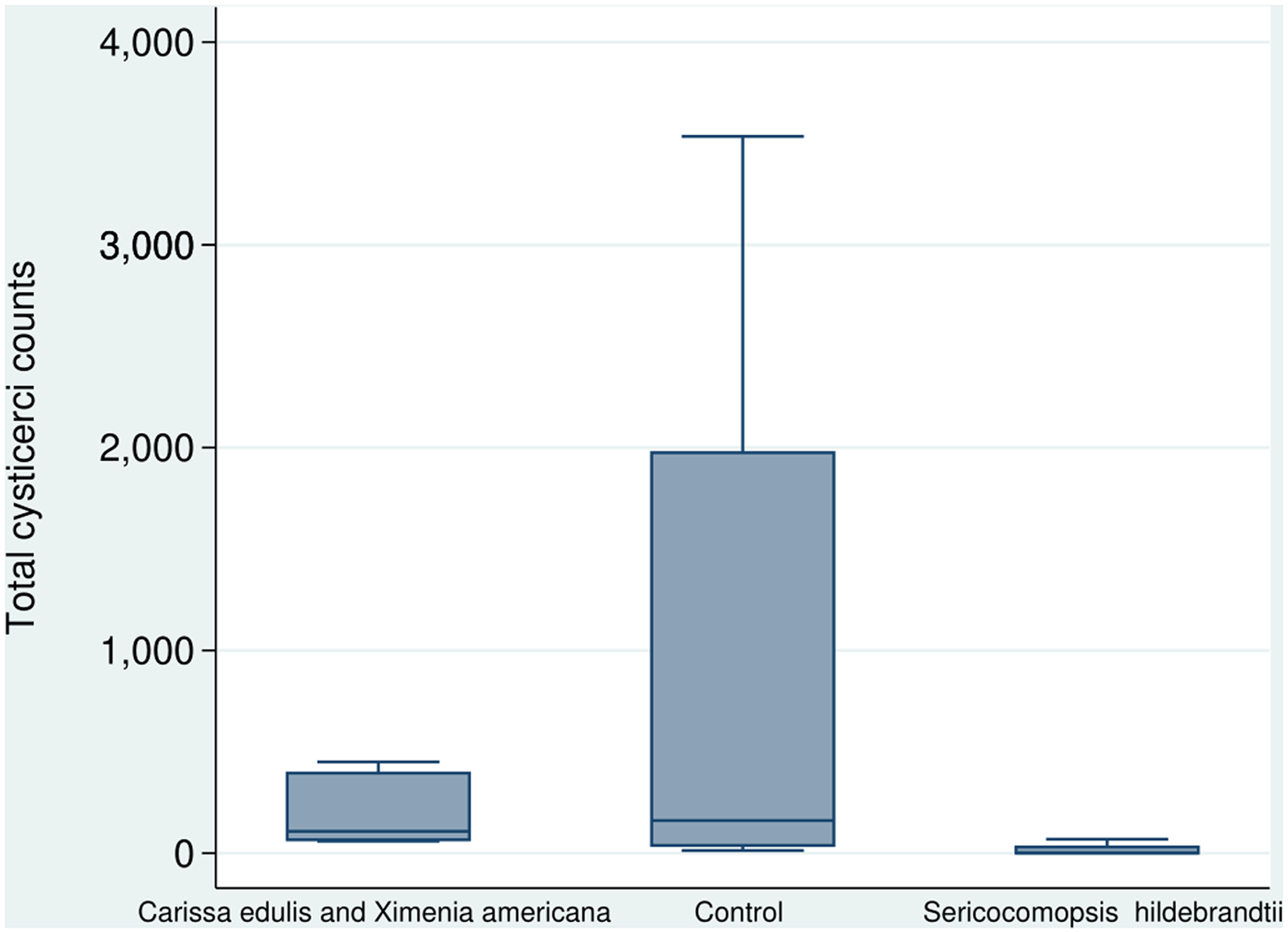

Kruskal–Wallis H test indicated that there was a significant difference in cysts counts between the groups (χ2 (2) = 11.3, p = .004) with mean ranks of 42, 84, and 105 for T1, T2, and T0, respectively. Dunn’s test for post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments indicated that T1 mean rank cyst count was significantly lower than that of the control group (p = .004); and of the T2 (p = .013). However, mean rank of T2 was not significantly different from that of T0 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A box plot showing total cyst counts of 21 pigs treated with Sericocomopsis hildebrandtii (8 pigs), a concoction of Carissa edulis and Ximenia americana (7 pigs), and a control group (6 pigs).

4. Discussion

This study showed that S. hildebrandtii was efficacious in treating pigs naturally infected with T. solium cysts, with no visible side effects. The plant material cleared all cysts from all examined predilection sites with no traces of visible degenerated/calcified cysts. The meat was also aesthetically clean and was passed for human consumption with no conditions. Therefore, these findings corroborate and validate the anecdotal reports regarding the plant’s efficacy.

However, S. hildebrandtii was not able to clear brain cysts in four pigs. Limited efficacy on brain cysts has been reported in previous studies with oxfendazole—a benzimidazole reported to be effective against porcine cysticercosis (Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Falcon, Gavidia, Garcia, Tsang, Bernal, Romero and Gilman1998; Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Bustos, Jimenez, Rodriguez, Ramirez, Gilman, Garcia and Peru2012; Mkupasi et al., Reference Mkupasi, Ngowi, Sikasunge, Leifsson and Johansen2013; Pondja et al., Reference Pondja, Neves, Mlangwa, Afonso, Fafetine, Willingham, Thamsborg and Johansen2012; Sikasunge et al., Reference Sikasunge, Johansen, Willingham, Leifsson and Phiri2008). Infected brain can pose a risk of infection to consumers, because the brain is not included in the routine inspection of pork. However, consumption of undercooked or raw pig brain has been reported to be relatively uncommon in endemic areas (Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Falcon, Gavidia, Garcia, Tsang, Bernal, Romero and Gilman1998). Thus, it is highly improbable that the cysts that survive only in the brain will perpetuate the parasite’s transmission.

The results showed that the concoction of X. americana and C. edulis reduced cyst counts, but the reduction was not statistically significant. The divergent results underscore the importance of validating indigenous ethnoveterinary knowledge.

Use of S. hildebrandtii can provide an affordable and an alternative option to oxfendazole. A recent field trial in Mbeya and Mbozi districts in Tanzania has shown promising results with the use of oxfendazole (Kabululu et al., Reference Kabululu, Ngowi, Mlangwa, Mkupasi, Braae, Colston, Cordel, Poole, Stuke and Johansen2020). However, although the drug has already been registered for use in Tanzania, it is yet to be available in the market. Hence, until oxfendazole becomes readily accessible to pig farmers, S. hildebrandtii can provide a solution against porcine cysticercosis in endemic areas in Tanzania.

Ethnoveterinary medicine is largely based on indigenous knowledge which is transferred orally rather than in writing (Bullitta et al., Reference Bullitta, Re, Manunta and Piluzza2018; Chinsembu et al., Reference Chinsembu, Negumbo, Likando and Mbangu2014). As a result, a great wealth of the knowledge remains undocumented and is therefore faced with a risk of becoming irretrievably lost to future generations due to rapid increase in urbanization and acculturation (Mahwasane et al., Reference Mahwasane, Middleton and Boaduo2013; McGaw & Eloff, Reference McGaw and Eloff2008; van Wyk & van Staden, Reference van Wyk and van Staden2002). Therefore, there is a pressing need to systematically record and document indigenous knowledge on ethnopharmacological use of plants, which should form a basis for their conservation. This study, therefore, apart from validating the efficacies of the plants, it contributes to the documentation of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants. We advocate for further ethnobotanical surveys, ethnopharmacological studies and development of ethnoveterinary pharmacopoeia.

This study is not without limitations. The treatments relied on prescriptions by the herbalists. It would have been interesting to observe the effect of different parts of the plants; and different dosing regimens in dose–response trial set-ups, for more informed inferences.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this experimental trial has validated purported efficacy of S. hildebrandtii against T. solium cysticercosis in naturally infected pigs. However, the study failed to demonstrate purported efficacy of a concoction of X. americana and C. edulis. The results highlight the importance of validating indigenous knowledge of ethnoveterinary use of plants. Further studies are necessary to validate, document, and conserve plants of ethnoveterinary importance.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the herbalists, Mr. Damiano Safari and Mr. Abogast Ako’onay for sharing their ethnoveterinary knowledge, and for helping with preparation of the herbal extracts. We also acknowledge the expertise offered by Professor R.P.C. Temu of SUA, in the botanical identification of the plants. We also thank Mr. Joseph Mlay (RIP) for helping with implementation of the trial and carcase dissections; and Mr. Felician Makiriye for conducting the pork inspection.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Government of Tanzania through the Zonal Agricultural Research and Development Fund (ZARDEF), under the Agricultural Sector Development Program Phase I (ASDP I).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authorship Contributions

M.E.B. conceived and designed the study. M.E.B. collected plant materials. M.E.B. and M.L.K. collected infected pigs. M.E.B. and M.L.K. performed the experiments. M.L.K. performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. M.E.B. and M.L.K. approved the final draft.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in this paper.

Comments

Comments to the Author: Interesting manuscript with promising results on the efficacy of Sericocomopsis hildebrandtii. Overall, the paper is well written and documented. It would have been nice to include a Oxfendazole treatment group (positive control)

Some major remarks pertain to the description of the methods and on the results and their interpretations.

M&M:

L90: Please provide some details on how the pigs were kept during the study (housing, group/individual, feeding, …)

L91: can you give more details on the weight of the pigs? They were all given the same dose of herbal extractions while the body weight may have been different.

Results:

L132: “…specific effect of the herbal materials”: what could be these specific effects?

L141-2: Very strange that no degenerated cysts were found in muscles and organs (other than the brain) of animals in the T1 group. It often takes more than 16 weeks for cysticerci to completely disappear after treatment. (same remark for L170-4 in Discussion)

Other comments:

L30: “infected” naturally infected

Fig 1: correct “21 pigs not included because due to …”

L184-5: “… counts, but the reduction was not statistically significant.”: if the reduction was not significant, it means that there is no reduction. Do also observe that the cyst numbers cannot be the same in all groups.