Introduction

The relationship between zoo visitors and animals, particularly nonhuman primates, is a complicated one and there is little consensus in the literature on whether visitors cause stress, provide enrichment or do not affect the animals (for a review see: Hosey, Reference Hosey2000). In primates, this relationship seems to be dependent on the species and sometimes the individual.

To further complicate this issue, modern zoos focus on providing visitor experiences that go beyond passively observing animals (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Kelling, Pressley-Keough, Bloomsmith and Maple2003). These experiences include activities such as interactions with keepers, animal training, and special events that occur outside of normal operating hours. While these extra activities/events enhance the zoo visitors’ experience, there has been little empirical research into how zoo events, aside from standard visitation, affect the welfare of the animals.

Objective

To begin to address the lack of information on zoo animal welfare during special events, we opportunistically studied how a new, late-night, haunted-house style event affected zoo animal behavior. During the event, visitors walked through the woods behind the animal exhibits and actors startled the visitors which often resulted in screaming and yelling. To explore whether this impacted the animals, we conducted a quasi-experiment on the behavior of spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi) comparing their behavior on event nights to control nights surrounding the event. As spider monkeys are typically diurnal, we believed they would be a good representative animal species to study.

Methods

We tracked the behavior of the spider monkeys (n = 4) during the two years the event ran (Friday and Saturday nights during October 2015 and 2016, the only time this event ever occurred) using night-vision goggles (Eyeclops Spy Gear 15 m Night Vision). We conducted scan samples (Altmann, Reference Altmann1974; every 10 minutes in 2015 and every 90 seconds in 2016) and recorded whether each monkey was active (any movement or eyes visible), resting (no visible movement) or inside (in their night building and not visible to the observers; the monkeys always had unrestricted access to the building). The difference in sampling frequency between the years was due to increased visibility in 2016 as we added an infrared home security light (LTIR50 DC12V 170 ft IR Night Vision Illuminator). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.

Results

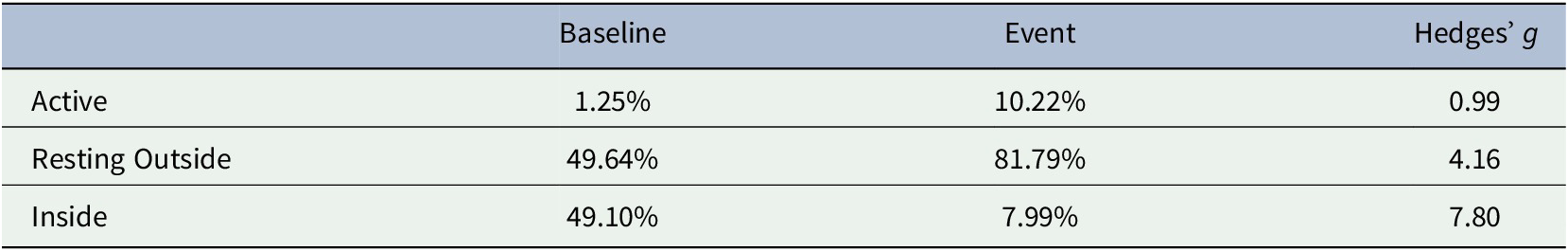

We compared the monkey’s behavior on baseline nights (8:30 pm – midnight; Thursdays and Sundays; n = 9) to event nights (8:30 pm – midnight; Fridays and Saturdays; n = 11). Because we had different numbers of scan samples in 2015 and 2016 and different numbers of baseline and event nights (due to an unrelated maintenance issue that resulted in the monkeys being kept in their night house during two of our planned baseline nights), we first converted our data into proportions of scans for each of our three behavioral categories for both event and baseline nights. We then ran z-tests for two proportions for each behavior, all of which were significant (see Table 1). The monkeys were more active, rested outside more frequently and spent less time inside during the event than during baseline observations. However, our data were not normally distributed, nor were they independent since the same individuals were used in both conditions, suggesting those results may be inaccurate.

Table 1. Percentages of Scans by Behavioral Category.

Therefore, we created a weighted average of scans and used an alternative statistical technique that does not require normality or independence (See Table 2). We calculated Hedges’ g, a measure of effect size for comparing means, to determine if there was a meaningful difference between event and baseline nights for each behavioral category (Hedges, Reference Hedges1981). All effect sizes were large (>.8; Cohen, Reference Cohen1988; See Table 2). As we found above, during the event the monkeys were more active and spent more time resting outside than on baseline nights, suggesting the event disrupted their typical nighttime behavior.

Table 2. Weighted Percentage of Scans by Behavioral Category.

We also conducted a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine whether there were any lasting effects of the event by comparing our baseline measures before (Thursday nights) and after (Sunday nights) the event. No differences were found in any of our behavioral categories (all p > .05). This suggests there were no longer-term effects of the event for the behaviors we measured.

Discussion

This late-night event changed the nighttime behavioral patterns of the spider monkeys. They spent more time outside and were more active during the event. However, the answer to what effect this event had on the animal’s welfare is much less clear, just as is the relationship between visitors and primate welfare during standard zoo hours (Hosey, Reference Hosey2000). As we can rule out no effect, we are left with the possibilities that the event was either aversive or enriching.

Even though we did not systematically take data on the monkeys getting startled, we often observed rapid head movements and scanning behavior immediately following the actors and visitors yelling and screaming. The startle reflex is widely considered an aversive reflex (see the following reviews: Davis et al., Reference Davis, Antoniadis, Amaral and Winslow2008; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley and Cuthbert1990), so it is possible the event was aversive to the monkeys.

However, it is also possible that the event was enriching. Moodie & Chamove (Reference Moodie and Chamove2005), concluded that brief threatening events can cause some of the same positive side effects as enrichment in cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus). It is possible that the screaming and yelling by visitors promoted similar positive responses in our monkeys. However, as the aversive nature of the startle reflex is well-established, we favor the explanation that the event may have been aversive, although future research should explore both of these possibilities. Specifically, physiological measures, such as fecal cortisol levels would be helpful in distinguishing between the competing explanations for the change we observed in the monkeys.

To limit any potential confounding effects of weather/season/month, we chose to use different days of the week, Thursday and Sunday, to obtain baseline measures while the event ran only on Friday and Saturday. As a result, there is a potential confound of the day of the week. Thus, it is possible that there is some other variable, perhaps crowd size, that influenced their nightly behaviors. We think this is unlikely as these individuals grew up in zoos and are well habituated to crowds. Therefore, a more parsimonious explanation would be that the novel event changed their behavior. Nonetheless, the question of whether crowd density during the day influences the nighttime behavior of the animals is certainly worth exploring in the future.

Conclusion

As zoos continue to seek more avenues for revenue, such as after-hours events, there should be an associated increase in monitoring animal welfare. It seems likely these events will affect the animals in some way, but more research should be conducted to determine how this affects the animal’s short and long-term welfare. Zoos should be particularly aware of the effect of events when they have animals that are more sensitive to environmental changes.

Author Contributions

DP and MS conceived the study. DP conducted the data collection and analyses. DP and MS wrote the article.

Funding Information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

Readers may contact DP if they want to access the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Comments

Comments to the Author: Overall this is an interesting and important subject for research, but some points need to be addressed before I would recommend publication.

Even though the authors state that the event was new, there is no data on the monkeysbehavior before the event. This is compounded by the fact that the event took place on the same days each week, so it is unknown what effect day is having on the data. This needs to be mentioned at least as a limitation. Other limitations should also be included.

The literature cited is quite old—there are newer articles on primates available.

As I don't have experience with Hedge’s g I’m sure the statistical reviewer will comment, but I believe confidence intervals should be included.

The wording of the Conclusion needs to be changed as there is no scientific evidence that the event was aversive to the monkeys. In addition, it is overreaching to say, in the Discussion, that the event was “likely…aversive” and instead should just suggest that it might be.

Because the results are so few, there is no reason not to include them in the text for easier accessibility, rather than in a table.