Introduction

Today, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, around 59.5 million people have been displaced by political, ethno-cultural and/or religious conflict, persecution, or disaster, and 19.5 million of them are refugees. Having triggered the worst refugee crisis since the Second World War, the war in Syria has left almost 12 million people in desperate need of humanitarian aid. There are currently 7.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), while over 4 million people have taken refuge in Syria’s immediate neighbourhood: Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq. 1 Among these countries, due to its open border policy, Turkey has received the largest number of Syrian refugees, who mostly originate from the Aleppo region in northern Syria. The main premise of this article is that Syrians living in Turkey in general, and in Istanbul in particular, have not only chosen Turkey as a refuge because of geographical proximity, but also because of historical, cultural and religious affinity stemming from the common Ottoman past. The main research question to be answered in this article is to what extent Istanbul provides Syrian refugees with a comfort zone, where they feel safe and secure in spite of the difficulties of everyday life.

This work is based on the findings of recent qualitative and quantitative studies conducted in six districts of Istanbul between the last quarter of 2015 and the first quarter of 2016. Both Syrian refugees and Turkish receiving community members and organizations have been interviewed in one-on-one interviews, focus group discussions and via structured questionnaires. Six districts in Istanbul, namely Küçükçekmece, Başakşehir, Bağcılar, Fatih, Sultanbeyli and Ümraniye, have been surveyed in order to identify the needs and vulnerabilities of the Syrian refugee population in Istanbul. In order to identify a random sampling of the target population, in line with the requirements of statistical analysis, the districts were chosen due to their diverse geographic locations in Istanbul (four on the European and two on the Asian side of the city). These districts host the highest number of Syrians in Istanbul that are underserved, and often subject to living together with other marginalized communities in the city such as Kurds, Alevis and the Roma. The needs assessment study has been carried out by the Support to Life Association (Hayata Destek Derneği) under the supervision of the author to collect data through a multitude of research technics: in-depth interviews conducted by Syrian-origin researchers as well as senior Turkish researchers in each of the six districts with key informants working in the host community for a total of 200 individuals. These included Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) conducted with both Syrian refuges (male and female) and the local host community members in each district (18 FGDs with Syrian refugees, six FDGs with host community members) with a total of 136 individuals; and Household (HH) Surveys that were conducted by Arabic-speaking Syrian assessment officers in each district with an estimated average of six individuals per household, amounting to a total of 124 surveys and 744 individuals. 2

The surveys and Focus Groups Discussions were conducted by Syrian researchers, who speak Arabic, Kurdish and Turkish (if necessary). The interviewers who conducted the structured surveys were themselves either ethnically Arabic or Kurdish Syrians, or Syrian-Palestinians. The survey questions were written in English and then translated by the Syrian staff into Arabic. The interview teams were between 20 and 30 years of age. The field officers worked in teams, generally one male and one female officer, but if the interlocutor was not comfortable, same-sex teams were assigned on demand. Essentially, if a woman was home alone and did not want a male in her home – the field supervisor would send two female officers to conduct the interviews. In-depth interviews with local stakeholders were conducted by Turkish-speaking Support to Life Association team members.

The structure of the article will be as follows: primarily, the universe of the research will briefly be elaborated on so that the reader will have an understanding of the major districts of the city of Istanbul, where most of the Syrian refugees have found refuge. Second, a short literature survey will be undertaken to depict the state of Refugee Studies in Turkey, which appear to have two missing elements, namely a historicist perspective and the agency of refugees themselves. Third, the legal status and the ways, in which Syrians have been framed by state actors since the early days of their arrival in Turkey, will be detailed in order to explicate the structural constraints that form the grounds for their societal exclusion and exploitation on the labour market as well as in other spheres of life. Fourth, the main scope of this article will be dedicated to discussing in detail the historical, cultural, religious and societal links bridging Aleppo and Istanbul, which provide Syrian refugees with a protective shield against the traumatic experiences resulting from the war and the act of resettlement. Eventually, the social networks followed by Syrian refugees and the sense of safety and comfort attached to them will be explained along with the testimonies from the fieldwork.

The Universe of the Research

The research has been conducted in six districts of Istanbul hosting a very sizeable group of Syrians: Fatih, Küçükçekmece, Başakşehir, Bağcılar, Sultanbeyli and Ümraniye. Fatih is a district located in the European part of Istanbul and is named after Sultan Mehmet, the Conqueror of Constantinopole. Fatih contains very cosmopolitan areas such as Aksaray, Fındıkzade, Çapa and Vatan Avenue. The district does not only host conservative background communities of Muslims but also many different international migrant communities ranging from transit migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa to Syrian refugees, Central Asian Turkic migrants, Russian tourists as well as Armenians, Georgians and many other groups. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Fatih is probably one of the most cosmopolitan urban spaces in the entire world. Besides its cosmopolitan context, it is also known for its extreme conservative image because of the religious community of the Çarşamba quarter within the district. Fatih also includes the historical peninsula of the city, Sultanahmet, with its historical Byzantine walls and very visible Ottoman heritage. It is this conservative, cosmopolitan and Ottoman heritage, that seems to be attractive to many Syrian refugees coming from Aleppo, which was the third most cosmopolitan Ottoman province after Istanbul and Izmir until the early twentieth century.Reference Watenpaugh 3 Fatih has recently become a diasporic space for Syrian Arabs, where they have constructed a new home away from their original homeland, a ‘Little Syria’. 4

Küçükçekmece lies on the European shore of the Sea of Marmara, in a lagoon named Lake Küçükçekmece. This district has recently hosted colossal public housing projects around the lake adjacent to old working-class neighbourhoods inhabited by many internally displaced Kurds originating from eastern and south-eastern parts of Turkey.Reference Kaya and Işık 5 These local Kurdish elements seem to have pulled Kurdish-speaking Syrian refugees to the district, who have followed already existing ethno-cultural networks.

Başakşehir is situated in the European part of Istanbul between the two ‘sweetwater’ reservoirs of the city, Büyükçekmece and Küçükçekmece lakes. This district is completely covered with large public housing complexes. This is why it offers a rich array of housing opportunities to these newcomers. Middle-class Syrian refugees also find it easier to be accommodated in this district due to such a rich housing market. The district has a huge service sector together with facilities of the construction business.

Bağcılar is also located in the European part of the city, neighbouring Atatürk Airport. This neighbourhood has only been urbanized throughout the last three decades. Most of the houses in Bağcılar have been illegally built, they are Gecekondu (shanty towns) that are now being replaced by rows of cramped apartment buildings built with minimal regulation. It is particularly in this district that many public housing constructions can be found. Bağcılar is now populated by new immigrants from the south-eastern parts of Anatolia, mostly young families, poor and internally displaced Kurds (IDPs).Reference Kaya and Işık 5 This district also hosts vibrant youth cultures, such as rap and graffiti. It is, at the same time, also a conservative, Islamist and right-wing stronghold with very strong support for the ruling AKP government. Bağcılar also houses a significant amount of industry, particularly textile businesses, printing companies, TV channels, a huge wholesale market for dry goods, a large second-hand car market, and many trucking and logistics companies. Similar to the former Kurdish origin IDPs, Syrian refugees mostly work in the informal labour market, predominantly in textile workshops and construction businesses.

Sultanbeyli is a working-class suburb on the Asian side of Istanbul. It is one of the electoral strongholds of conservative-Islamist political parties, such as the ruling AKP government. This district houses several different religious communities attracting Syrian refugees as well. Ümraniye is one of the largest working-class districts in Istanbul. Formerly, it was a gecekondu district hosting domestic migrants coming from eastern and south-eastern parts of Turkey until the 1990s. Textile, construction and service sectors are very present in the district, and these sectors attract Syrian refugees looking to find jobs in the informal economy.

The State of Refugee Studies in Turkey

This study, which we have conducted in Istanbul, certainly falls into the category of Refugee Studies, which is a rather newly developing field. Dawn Chatty and Philip Marfleet explain very eloquently how Refugee Studies was first born in the 1980s as a state-centric discipline and, like many other disciplines, it defended the interests of nation-states, and also how it became more critical in due course.Reference Chatty and Marfleet 6 There are two essential elements that seem to be missing in Refugee Studies in Turkey. First, scientific studies conducted in Turkey regarding the situation of Syrian refugees often contribute to their statisticalization rather than to making their social, economic and political expectations visible to the receiving society.Reference Gümüş and Eroğlu 7 Most of the studies in Turkey are either quantifying refugees or concentrating on the host society’s perceptions of refugees. What is missing here is the lack of anthropological research permitting the refugees to speak for themselves. As Gadi Benezer and Roger Zetter once stated very well, such an anthropological research could make it potentially easier to occupy a space within the host population as well as in the public domain.Reference Benezer and Zetter 8 A point of view can be offered that includes, beside their trauma and sufferings, their active rather than passive stance and their resourcefulness, motivation and commitment that was needed to escape from their homelands and sanctuary.

Furthermore, what is also missing in Refugee Studies in Turkey is a retrospective analysis of refugee experiences in the country dating back to the early ages of the Republic as well as the Ottoman Empire. This is not only the missing link in the Turkish Refugee Studies field, but also the missing element in Refugee Studies in the rest of the world. Philip Marfleet relates this problem to the limitations of the nation-states: ‘If the territorial borders of modern states confined some people and excluded some others, “nationalized” intellectual agendas have largely excluded migration as a legitimate area of study.’Reference Marfleet 9

Anatolia throughout history has been exposed to several different forms of refugee and migration practices. Since the Byzantine era, Anatolia has hosted many different groups of people who found refuge in there. Anatolia has become gradually Muslimized throughout history along with the migration of dominantly Turkish and Muslim-origin populations. Jewish migration to the Ottoman Empire after their expulsion from Spain and Portugal in 1492 was an exception. The Muslimization of Anatolia became even more visible in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire were shrinking rapidly.Reference Erdoğan and Kaya 10 The expulsion of Crimean and Circassian Muslims escaping from the atrocities of the Russian Empire in the second half of the nineteenth century was comparable in terms of size to the migration of Iranians, Turks, Kurds, Bosnians, Kosovars and Syrians escaping the violent conflicts in the Middle East and the Balkans starting in the early 1980s.Reference Kaya 11

The first wave of refugees in modern times was from Iran, following the 1979 Revolution. Other major refugee flows were Kurds escaping from Iraq in 1988, which numbered almost 60,000; and in 1991, when half a million people from Iraq found safe refuge in Turkey. In 1989, with Bulgaria’s ‘Revival Process’, which was an assimilation campaign against minorities, almost 310,000 ethnic Turks sought refuge in Turkey. In the following years, during the wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, Turkey granted asylum to 25,000 Bosnians and 18,000 Kosovars.Reference Kirişçi and Karaca 12 Turkey has been positioned on the transit route for irregular migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Iraq, Iran and Pakistan since the 1990s.Reference İçduygu 13 Turkey is also a destination for human trafficking in the Black Sea region, with victims usually coming from Moldova, Ukraine, the Russian Federation, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. In the meantime, Turkey has long been a country of destination for immigrants from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, as these new immigrants see Turkey as a gateway to a new job, a new life, and a stepping stone to employment in the West.Reference İçduygu 14 Its geographical location has made Turkey a crucial place on irregular migration routes, especially for migrants trying to move to EU countries. Turkey’s position in the migration process is a unique one and it is becoming an important site, not just for new national settlers, but also for today’s international settlers. Turkey, and especially Istanbul, has become a more complicated site demographically with the new arrivals and other international migrants, mostly originating from the EU countries, especially from Germany and Russia. 15 Obviously, Turkish migration and asylum laws and policies were not able to meet the needs of these radical demographic changes resulting from global and regional transformations. Thus, migration and asylum laws and policies had to go through a substantial review process to prepare the country to come to terms with the changing conditions in the region.

Legal Framework: Guests, but not Refugees!

From the very beginning of the refugee flow into Turkey, Syrians have officially been called ‘guests’ but not ‘refugees’ because Turkey officially does not accept refugees other than those coming from outside its western boundaries in accordance with the geographical limitation clause of the 1951 Geneva Convention on the Protection of Refugees. Although the geographical limitation was removed for most of the members by the 1967 Additional Protocol of the Geneva Convention, Turkey decided to keep it, together with Congo, Madagascar and Monaco. However, Turkey introduced a Temporary Protection Directive for the refugees in 2014, based on Articles 61 to 95 of the Law on Foreigners and International Protection, which came into force in April 2014. The directive grants almost all social and civil rights that refugees enjoy in western societies. 16 Accordingly, Turkey has provided Syrians with temporary protection, which consists of three elements: an open-door policy for all Syrians; no forced returns to Syria (non-refoulement); and unlimited duration of stay in Turkey.

However, those enjoying temporary protection have not been allowed to apply for individual refugee status determination, which means that they did not receive the opportunity to be resettled in a third country through the mechanisms of UNHCR. A large number of Syrians are not willing to register with the Turkish authorities so as not to lose their right to be resettled in a third country, preferably Germany. While an open-door policy is still being implemented, Syrians, then, are labelled ‘guests’ instead of ‘refugees’. ‘Guests’ are expected to leave the host country and return to their homeland at some point.Reference Korkut 17 Therefore, the length of their stay is of a limited nature, unlike that of ordinary citizens. Turkey does not grant legal refugee status to refugees from outside of Europe, depriving them of the rights and benefits they would otherwise enjoy as registered refugees. Using the term ‘guest’ instead of ‘refugee’ also indicates the AKP’s perception of the Syrian refugee crisis, based on the assumption that ‘guests’ are people whose stay will be subject to the benevolence of the host state actors for a temporary period, but not on a permanent basis.Reference Eroglu 18

Despite the rights granted under the Temporary Protection Directive dating from 4 April 2013, refugees have encountered huge problems in the spheres of health, education, labour market, and housing in Turkey. 19 Due to the fact that there are not very reliable and sufficient official data on the social-economic status of refugees, one cannot correctly make estimations about the number of refugee children who actually do enjoy the right to primary education, or of refugees who do have access to health care, or those given the right to work. It is estimated that around 30–35% of Syrian refugees in Turkey are school-aged children. This amounts to around 800,000 children that need to be attending school. While AFAD (Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Directorate) is providing education for children in 70 schools and the Ministry of Education is offering it in approximately 75 locations outside the camps, the number of children receiving education is around 300,000 compared to the half a million who need it. It is simply not feasible to accommodate such a high number of school children in the national education institutions in the entire country (Ref. Reference Gümüş and Eroğlu7, Kilic and Ustun). There is also anecdotal evidence that there is only one pharmacy left in Istanbul offering free-of-charge medication to refugees due to the allegations that pharmacies are not being reimbursed by AFAD, which has been the lead agency in coordinating the government’s efforts to respond to the refugees’ needs. It can easily be imagined what a difficult situation this fact might leave refugees in, especially those with chronic diseases, or pregnant women and, especially, children. In addition, despite the temporary protection regime, Syrian refugees seem to have limited freedom of movement when it comes to lucrative holiday resorts: Syrians were told to leave Antalya and, now, also Muğla, two provinces located on the Turkish Riviera, in order not to damage the large business interests of the tourism industry. 20

The first group of Syrian nationals coming into Turkey found refuge when crossing into the province of Hatay on 29 April 2011. Initially, the AKP government expected that the Assad regime would soon collapse and it estimated that at most around 100,000 Syrians would stay in Turkey for about 2–3 weeks (Ref. Reference Gümüş and Eroğlu7, Erdoğan). Following the escalation of local conflicts in Syria, the AKP government declared an open-door policy for Syrian refugees in October 2011 (Table 1). Accordingly, Turkey has allowed Syrians holding a passport to enter the country freely and even treated those without documents in a similar welcoming way; it has guaranteed the principle of non-refoulement; offered temporary protection, and has committed itself to providing the best possible living conditions for, and humanitarian assistance to, the refugees. 15

Table 1 Estimated number of Syrian refugees living in and outside official refugee camps (11 March 2016, Ministry of Interior). 21

However, the number of Syrian refugees, who leave Turkey for Europe, has drastically increased in 2014 and 2015. Most refugees going to EU countries either sailed from Turkish coasts to the Greek islands, or crossed Turkey’s borders with Greece and Bulgaria. 22 The perils of the sea journey – shipwrecks with many missing and dead – have not deterred many Syrian refugees. Some were prepared to make this journey at all costs. The situation has changed though after the agreement made between Turkey and the EU on 18 March 2016, resulting in stricter surveillance of the Aegean coasts by the Turkish security forces, and thus with the decline of the refugees trying to cross the sea.Reference Collett 23 Many of those refugees have already been in Turkey, but others have only recently left Syria to try to cross into Europe via Turkish coastal towns such as İzmir, Bodrum and Ayvalik. Apparently, Syrian refugees are discontent about their status in Turkey. They ‘remained unsure of what they could expect in terms of support from the Turkish authorities and how long they would be welcome’. 24 However, even if it is true that some of the Syrians who have lost their hope of returning home and cannot envisage a future in Turkey due to growing racism, misery, exploitation and domestic political problems in Turkey, and the unstable political climate, one should not forget that a very small minority of the Syrians who managed to cross to the Greek islands had spent a short period of time in Turkey prior to their journey to Greece. More than 80% of the Syrians who settled on the Greek islands reported that they only spent a few days in Turkey to prepare for their journey to Greece. Only 20% of those reported that they had spent more than six months in Turkey prior to leaving for Greece. 1

Many Syrian refugees in Turkey have already lost hope concerning the ending of armed conflicts in their homeland. Owing to the ambiguous status granted to them under the Temporary Protection Regulation, most of the Syrian children cannot enrol in proper education; men and women have been recently granted the right to work in February 2016; they have been exploited on the labour market; they are being exposed to xenophobic attitudes; and they are not able to apply for permanent residence permits.Reference Öner and Genç 25 The Transatlantic Trends Survey of the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) held in 2014 provides further evidence for the worsening perceptions of immigrants in Turkey. 26 According to this survey, 42% of the Turkish population think that there are too many foreign-born people in Turkey, a 17 percentage point increase over 2013. Moreover, 66% of the respondents from Turkey support more restrictive policies toward refugees. In the World Values Survey covering 51 countries, Turkey is ranked in 13th place – third on the European continent – in terms of intolerance toward immigrants and foreign workers. The results from the Life in Transition Survey II (LITS2) conducted in 2010, named Turkey as the most intolerant nation among 34 European and Asian countries, and tied with Mongolia. Although negative perceptions about immigrants have increased in one year and there is a strong support for restrictions in Turkey’s policies toward refugees, this issue had not yet transferred into the political sphere in 2014. Then, only 4% of Turks said that immigration was Turkey’s most important problem.Reference Erdoğan 27

The framing of the refugee reality by state actors as an act of benevolence and tolerance has also shaped public opinion in a way that has led to the exposure of some racist and xenophobic attitudes vis-à-vis refugees. This is why it is not a surprise that Turkish society has witnessed several lynching attempts, stereotypes, prejudices, communal conflicts and other forms of harassments performed against Syrians.Reference Gökay 28 The massive increase in the number of refugees outside camps and the lack of adequate assistance policies toward them has aggravated a range of social problems. Refugees experience problems of adaptation in big cities and the language barrier seriously complicates their ability to integrate into Turkish society. There are several problems the Syrians have been facing in everyday life. There is now a growing concern about underage Syrian girls being forced into marriage as well as fears that a recent constitutional court ruling decriminalizing religious weddings without civil marriage will lead to a spread of polygamy involving Syrian women and girls.Reference Kirişçi and Ferris 29 The sight of Syrians begging in the streets is causing particular resentment among local people, especially in the western cities of Turkey. There have also been reports of occasional violence between refugees and the local population. In turn, this reinforces a growing public perception that Syrian refugees are associated with criminality, violence and corruption. These attitudes contrast with local authorities’ and security officials’ observations that in reality criminality is surprisingly low, and that Syrian community leaders are very effective in preventing crime and defusing tensions between refugees and locals.Reference Kirişçi and Karaca 12

At times of economic and political instability, the nationalist and populist agenda has become more visible, and authorities attempt to generalize hostility towards others who are culturally, ethnically and religiously different. Refugees are easily portrayed as inferior, malign, dangerous or threatening.Reference Wodak and van Dijk 30 Lacking resources of public communication and relevant language skills, most of the refugees are unable to contest such labellings, stereotypes and xenophobic attitudes generated by the majority society.Reference Marfleet 31 Such a xenophobic discourse was also employed by the main oppositional parties prior to the 7 June 2015 General Elections in their electoral campaigns. The Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Action Party (MHP) used a populist discourse scapegoating the Syrian refugees for the political, social and economic ills in Turkey. The Syrian refugees were instrumentalized by both parties to express their critics against the AKP, which they blamed for deepening the Syrian crisis in the first place, thus leading to the massive migration of Syrians to Turkey at the expense of Turkish citizens.Reference Werz, Hoffman and Bhaskar 32 Upon growing criticisms coming from civil society organizations and academics, it should also be noted here that both parties, especially the CHP, gave up such discourses prior to the second general elections held on 1 November 2015, and have since then used a rather constructive and friendly discourse vis-à-vis the Syrians.Reference Canyaş, Canyaş and Gümrükçü 33

A Tale of Two Cities: From Aleppo to Istanbul

There are several factors that laid the ground for the Syrian Civil War. Sociopolitical, environmental and economic elements such as unemployment, climate change, drought, water management stress and poverty can be counted as some of the elements elevating the risk of a civil war. The unemployment rate in Syria used to be relatively moderate compared with other countries in the Middle East; however, the youth unemployment rate was always high. The unemployment rate among youth aged between 15 and 24 stood at 26% in 2002, close to the Middle Eastern average.Reference Kabbani and Kamel 34 What distinguished the Syrian case was that unemployment rates among young people were more than six times higher than those among adults, the highest ratio among the countries in the Middle East. This high rate of unemployment among the youth population triggered dissatisfaction against the regime of the Ba’ath Party and caused a brain drain of skilled workforce in the country. Other important factors, which are often neglected and yet are hugely important are climate change and droughts.Reference Leighton Schwartz and Notini 35 Seven significant droughts occurred in Syria between 1900 and 2011, where the average rainfall dropped to one third of the normal level.Reference Gleick 36 The latest drought, which started in 2006, was described as the worst long-term drought, and most severe set of crop failures since agricultural civilizations began and caused agricultural failures, economic dislocations and population displacement. These effects are attributed by some experts to be playing an essential role in spurring violence in the country.Reference Femia and Werrell 37 During the civil war, access to clean water also deteriorated, threatening the health of the population. In 2013, UNICEF found that water availability in conflict-affected areas decreased to only one quarter compared with pre-crisis levels. 38

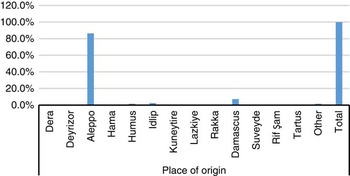

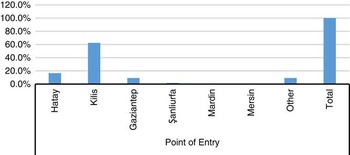

The study on the Vulnerability Assessment of Syrians in Istanbul has found that around 87% of Syrians in Istanbul originate from the province of Aleppo, while only a small minority of 7.2% came from Damascus (Figure 1). A majority of the interlocutors interviewed (62.5%) entered Turkey through the Syrian border in Kilis, a south-eastern city, while 16.7% entered from Hatay, and 9.2% from Gaziantep. Many of the interlocutors later followed their ethno-cultural and kinship networks, leading them to Istanbul. In conflictual situations threatening the lives of locals, migrants are tempted to go to the remote places, as far as their economic, social and cultural capital permits them to do so. Similarly, the reason why there are so many Syrians residing in the south-eastern cities of Turkey such as Gaziantep, Hatay, Kilis and Şanlıurfa is again not only because of their geographical proximity but also because of kinship relations dating back to the Ottoman era when all those cities were administratively linked to the Aleppo province (Vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire. In the same way, Assyrian Christians, Circassians and Yezidis found refuge in those cities where their kin had settled during the Ottoman Empire, such as Istanbul, Mardin and Şirnak.Reference Korkut 17 This is what Nicolas van Hear has already indicated elaborately in his works on diasporas.Reference van Hear 39 The same inclination can also be found among Kurdish internally displaced persons, who had to leave their homelands in the south-eastern parts of Turkey to go to different cities in the country, and even abroad if possible, since the mid-1990s.Reference Kaya and Işık 5

Figure 1 Place of origin of Syrians in Istanbul.

With the conflict in Syria still going on, refugees are increasingly moving inland, beyond the border provinces. The Turkish Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) has reported that 220,000 Syrians (or 12% of the entire Syrian refugee population in Turkey) are registered in Istanbul as of March 2015. By July 2015, the number increased to over 317,000 with an increase of 64%, while figures reached 395,000 by March 2016, particularly as irregular migration into Europe has increased. In the second half of 2016, some estimates are even as high as 550,000 and these numbers are still growing. In just a four-month period between March 2015 and July 2015, the number of registered Syrians in Istanbul has increased by 64% (Figure 2). There are many reasons for families and individuals to move away from camps, and, as shown by previous research, many chose to relocate to urban centres due to the freedom of mobility, which allows Syrians an opportunity to find networks. Additionally, urban settings potentially allow for better housing, better educational opportunities and more diverse, stable employment opportunities. Of course, the perception gap between urban settings and the reality, especially in a major metropolitan city, cannot be denied. Istanbul is the most attractive city where Syrian refugees of all ethnic backgrounds prefer to settle.

Figure 2 Point of entry into Turkey.

One of the most striking images about Aleppo was portrayed on 17 August 2016 when the video of a five-year-old boy, Omran Daqneesh – showing him sitting dazed and bloodied in the back of an ambulance after surviving a regime airstrike on the rebel-held Qaterji neighbourhood of Aleppo – was circulated on YouTube by the Aleppo Media Centre, an anti-government activist group.Reference Hunt 40 Following the images of Ailan Kurdi’s dead body on the Aegean shores of Turkey in the summer of 2015, Omran became another icon symbolizing the devastation and tragedy caused by the war in Syria, and all other wars. Like most Syrians residing in Turkey, Ailan was also from the Province of Aleppo.Reference Smith 41

Aleppo is one of the 14 provinces of Syria, located in the northern part of the country between Idlib in the west, Hama in the south and Ar-Raqqah in the east. Before the war, it was the most crowded province in Syria with a population of more than 4,868,000 in 2011, almost one quarter of the total population of Syria. The province of Aleppo is the fifth largest province of Syria. Its capital is the city of Aleppo. The city of Aleppo was the second largest city in Syria with a population of more than 1.5 million people. It was the country’s most important centre for trade and manufacture, and its central market area – souq (bazaar) – used to stretch out for more than 10 km in the middle of the city. There were small shops, stalls, warehouses and workshops crowding the narrow streets and alleys. The Aleppo souq was very important for the local, regional and national economy, but it had also become a tourist attraction, and it was described in glowing and romantic terms in local and foreign guidebooks. The unchanging and historical nature of the souq was highlighted, and the economy and ethos of the souq were portrayed as radically different from the rest of the city. Such descriptions fit into a ‘culturalistic’ view where the Middle Eastern souq was regarded as a symbol of tradition, unaffected by social change, and where people working there were bound together by affective ties.Reference Rabo 42 These depictions have been paraphrased in the words of Annika Rabo, a social anthropologist, who conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Aleppo between 1997 and 2003. The city is in ruins now and its inhabitants have scattered, mostly to Turkey. The reason why almost all of the former inhabitants of the province of Aleppo have found refuge in Turkey is not its geographical proximity. The reason is more complicated, and there are strong historical, cultural and religious links between Aleppo and Anatolia dating back to the Ottoman Empire. In what follows, I give a more detailed depiction of the history of the city, which can be traced back to the Ottomans.

Ottoman authorities did not tally people using modern notions of race or ethnicity, but instead counted people according to religion. However, the population description from the 1903 edition of Aleppo’s Salname, the provincial yearbook, provides a hint of this continuing cosmopolitanism, as well as changes in the bureaucratic formulation of difference.Reference Watenpaugh 3 It is recorded that in Aleppo there were Muslim Turks, Arabs, Turkomans, Circassians, Kurds, Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholics, Armenians, Syriacs, Maronites, Protestants, Chaldeans, Latin Catholics and Jews. A plurality of the city’s inhabitants consisted of Turkish or Arabic-speaking Sunni Muslims, and 30% of the city’s population were Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews (both Mizrahi and Sephardic). 43 By 1922, alongside Beirut, it had become the chief resettlement centre for more than 50,000 primarily Turkish-speaking Armenian refugees from Anatolia. In the aftermath of the Ottoman hegemony (1918), most of the Turks were asked to leave the city by the pan-Arabic nationalists guided by Prince Faysal, the Emir of Hijaz, who obtained the support of the British and had embarked upon the ‘liberation of the nation’. Prince Faysal was a member of the Hashemites originating from the Prophet Mohammad’s lineage. The latest demographic data about the city are available from the 1957 census, and the data show that the city was mainly populated by Sunnis (1,045,455) and Christians (around 150,000) (Table 2).Reference Watenpaugh 3

Table 2 The Population of Syria by religious communities and Muhafaza in 1957.

Source: Etude sur ‘La Syrie Economique 1957’, Annex 8. (Minor discrepancies in totals are due to the original source.)

In the early days following the end of the First World War, a secular form of pan-Arab nationalism made it possible for the inhabitants of Aleppo to live together in peace. A striking feature of the pan-Arab nationalism was that it was mainly constructed as a response to the pan-Turkist ideology of the Ottoman elite, which had become outspoken and popular among Turkish nationalists in the late nineteenth century.Reference Çatı 44 Pan-Arab nationalism was based on the secular idea that the Arab is a non-sectarian designation and that Muslims, Christians and Jews could be equally Arab and possess the same rights to full citizenship. In this version of Arabism, Islam had no role in governance or a basis of legitimate authority. It should be recalled that Islamism in the Arab world partly emerged as a reaction against the imperialist division of Ottoman Muslims into separate states and the non-sectarian, emancipatory and bourgeois dimensions of interwar liberal Arab nationalism.Reference Watenpaugh 45

Following the Social Networks

Almost half of the interlocutors who were interviewed arrived in Istanbul in the previous one or two years (46.4%). On the other hand, 17.6% stated that they have been in Istanbul for the last three to four years. Thirty-six percent of the interlocutors stated that they have only recently arrived in Istanbul (Figure 3). This finding indicates that there will be more to arrive through their networks. There are several theories, such as the push and pull theory and the rational choice theory, that can be used to define the reasons and motives of migration. Probably, the Network Theory is the most applicable one to the case of Syrian Refugees living in Istanbul. The Network Theory is one of those theories that try to provide an empirical explanation of migration motives. Networks can be regarded as one of the main reasons of migration and serve as strong ties between migrants and potential migrants.Reference King 46 These connections often become a social formation, which helps potential migrants as well as new migrants find their ways in society where the old migrants have already established their lives. There are three types of networks: family networks, labour networks and ‘illegal’ migrant networks.Reference Boyd and Nowak 47 Labour networks are used widely, and it seems that they are also explanatory for the case of Syrian refugees. Labour networks are widely applied in the process of migration. Not only do they help potential migrants in obtaining information about the availability of job vacancies, but also help new migrants settle before starting a job. Even though applying to labour networks might be helpful, it should be highlighted that they cannot always be trusted. During the interviews, several interlocutors stated that their jobs had been provided to them via labour networks but then turned out to have poor working conditions as well as low salaries, which were not provided on time either.

Figure 3 Arrival time in Istanbul.

Second, family networks provide new migrants with the feeling of hospitality, familiarity and help them preserve their culture and close ties with their families.Reference Castles, Miller and de Haas 48 According to Charles Tilly, even though networks can be beneficial, they may also create problems for the people who do not accomplish their commitment to society.Reference Tilly 49 Being a member of a network comes with obligations, and once the mission is not fulfilled it may cause exclusion of individuals from the networks. The other type of networks is illegal networks, which include human trafficking and smuggling. As noted by Boyd and Nowak, illegal migrants try to have fewer ties with family or labour networks.Reference Boyd and Nowak 47 Accordingly, they do not engage in legal networks, but they try to find jobs through illegal connections. In this fieldwork, we have not come across such networks as reported by the interlocutors.

Potential migrants and refugees tend to choose their places of migration according to the countries where they already have friends or family members or people they know, who come from their home countries. In this way, they can easily get information about the city they are planning to migrate to.Reference King 46 The information reduces anxiety that potential migrants tend to have before they make a decision about their destination. Networks can be regarded as one of the important clusters among migrants’ location choices. On the other hand, having networks eases the process of making decisions about the country of migration and renders the process of integration much faster. Therefore, having networks in the country of destination can be one of the main reasons for migration for refugees, as well as for regular migrants.Reference King 46 Once the first wave of migrants has settled in the new places of residence, they assist family members or friends to join them. Accordingly, the migration process for the second wave is made easier considering the costs and risks. Due to having information about previous examples, the migrant has the feeling of security and protection. This is what our research team has come across very often in the field. Most of the refugees try to establish stronger ties with previously migrated people to reduce their own costs and risks.

Even though one of the strongest components of the network theories can be the family networks, weak ties may also play a significant role in the migration process.Reference Tilly 49 Relations between refugees and potential refugees may be weak, but once they are in a foreign environment these ties become even closer as they share the same language, ethnicity, culture and religion. Therefore, they develop a mutual reliance on each other. This is what we have observed in focus group meetings, where we encountered many refugees originating from different cities and neighbourhoods in Syria, and who have established closer links in their places of residence in Istanbul. These relations often turn into close friendships as they try to provide information for each other, reducing costs and comforting and consoling each other in terms of relieving the pains experienced in the migration process. Most importantly, new refugees are eager to get familiar with the experiences of the people who have migrated before them. It should be highlighted that networks, as one of the significant reasons for migration, have become more evident and useful as the internet has become more accessible to the wider society. Networks may also play a significant role before the act of migration. Being aware of existing networks, potential migrants are likely to walk the same path already experienced by other refugees, rather than taking the risk of migration without any actual information.Reference Massey and García-Espańa 50 Such networks have the potential of providing refugees with a shield, protecting them from the detrimental effects of a difficult journey and everyday life, as well as with a sense of ethno-cultural, religious and linguistic familiarity that gives them comfort in the land of the unknown. Thanks to the growing visibility of the internet in everyday life, refugees have been utilizing such networks to decide about their routes.Reference Rebmann 51

Istanbul is Safe despite Everything!

Survey results have shown that the primary rationale behind moving to Istanbul is to find a job (54.8%). The second most expressed reason is to follow existing social networks such as family ties, relational links and other relevant social, ethno-cultural and religious networks. The third reason for refugees to settle in Istanbul seems to be providing security and safety for their families (Figure 4). What is striking here is the very low percentage of Syrians who are willing to live anywhere other than Istanbul. One could argue that Syrians residing in Istanbul are rather satisfied with where they are, and they are not considering going elsewhere, such as for instance EU countries.

Figure 4 Reasons of settlement in Istanbul.

Marwa, a 28-year-old female living in the Sultanbeyli district on the Asian side of Istanbul, utters her feelings about Istanbul with the following words:

I feel safe here in Istanbul, and I don’t want to go back to Aleppo where we were moving from house to house due to the war. I want to stay here in Turkey, because it is similar to our traditions and culture, and my family is here. I don’t want to go to Europe either, because I have no one there. And I don’t want to go back to Syria at all, because I lost my husband there.

What attracts her to Istanbul is the cultural affinity to the city as well as familial links already existing there. The research, which we have conducted together with the Support to Life Association, was undertaken in districts where mostly Sunni Arabs are residing. The staff of the Migration Unit of the Şişli Municipality in Istanbul have reported that, in some parts of their districts, there are many Kurdish-origin and Alevi-origin Syrians who have been searching for comfort in their own already- existing social networks, constructed by the Kurdish and Alevi inhabitants living mostly in Okmeydanı, one of the strongholds of left-wing oppositional groups with a working-class and ethno-class background. 52

When refugees were asked about how safe they feel in Istanbul, the majority have expressed feelings of safety (91.8%) while only 6.8% stated an uneasiness regarding safety in the city. Being away from the war zone and everyday terrors of violence in Aleppo, coupled with cultural and religious familiarity, have been reported as the main determinants of a feeling of safety and comfort for refugees in Istanbul, although women tend to feel slightly more towards the extremes in terms of safety and insecurity in the city compared with Syrian men, who are in the more moderate to safe range of the spectrum. Mohammad, a 27-year-old male who we interviewed in Ümraniye, explained his reason of picking Istanbul to live, in the following words:

I came here two years ago through the Turkish-Syrian border. I had to pay a lot of money to the smugglers. Turkey was my first choice, because there is better treatment here compared to other neighbouring countries in the region. And I feel safe here in Istanbul.

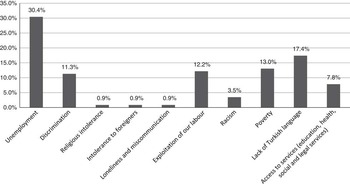

Syrian refugees were also asked to report about the problems that they face in everyday life: 30.4% of the interlocutors complained about unemployment, while others respectively complained about their lack of knowledge of the Turkish language (17.4%), poverty (13%), exploitation (12.2%), discrimination (11.3%), and limited access to social services (7.8%) (Figure 5). Poverty, exploitation, exclusion, and discrimination are the major problems stated by refugees. The cross-tabulations by gender indicate that women tend to feel more exposed to discrimination and racism in everyday life. Focus group discussions reveal that women are in a situation to negotiate more in everyday life with the members of the majority society, with respect to handling the relations within their neighbourhood. Women are confronted with more problems while carrying out household chores and caring for family members, such as buying groceries, the schooling of children, seeking health care, and finding their way around the city.

Figure 5 Primary problem faced in Istanbul as a Syrian.

Abo Bashar, a 55-year-old male residing in Ümraniye, has drawn our attention to the difficulties of living in a city such as Istanbul, though he has added that he is happy there:

I am happier here though it’s hard. Because the treatment here is better than it is in the other countries. I am not planning to travel to any other country, but will go back to Syria one day. We wish that we had a work permit, and that the employers paid us a better salary. We don’t want to work under such conditions. We wished people here would treat us better and give us more assistance because we receive nothing. And we wished the landlords would go easy on us and take from us what the contract says they must take.

The will to return to Syria is still very strong, but of course it all depends on the political situation in the homeland.

However, among the Syrians we interviewed there is a very critical group of people who expressed their unwillingness to return to Syria under any condition. Around 20% of the people interviewed expressed their unwillingness to go back home. It was later found that this group corresponds to those who lost loved ones in their immediate families (Figure 6). Hence, one could argue, that at least those who have lost family members in the civil war are not willing to go back, at least for the time being, due to the traumatic experience resulting from their losses.

Figure 6 Missing family members in the war?

Conclusions

This research, which has been conducted in six different districts of Istanbul (Küçükçekmece, Başakşehir, Bağcılar, Fatih, Sultanbeyli and Ümraniye) run by mayors of the Justice and Development Party, has revealed that Syrian refugees residing in these districts predominantly originated from Aleppo, which was the third most cosmopolitan city of the Ottoman Empire after Istanbul and Izmir. It has been argued that refugees follow already-existing social, ethno-cultural and religious networks, the origins of which could be found in the past. Most refugees stated that it is this cultural and religious affinity, which has made them feel rather comfortable in Istanbul. A majority of the interlocutors also said that one reason why they have chosen Istanbul is the feeling of security and safety that the city provides them with.

However, they also have many complaints. Exploitation on the labour market, the lack of knowledge of the Turkish language, discrimination in everyday life, lack of empathy among the locals towards their suffering, stereotypes and prejudices generated by the locals, the lack of education facilities for their children, the lack of a proper legal status, the lack of the right to work legally, the lack of the right to health services, the lack of the right to housing, the lack of future prospects in this country, the lack of integration policies at central and local levels, the lack of social and political recognition, respect and acceptance, and the ways in which they are labelled by the central state as ‘guests’, are some of the problems they face in everyday life. It is exactly these problems which, in the end, prompt some refugees to leave Turkey at the expense of risking their lives at the border.

Nevertheless, what came as a surprise is the very low number of refugees among those interviewed who stated their willingness to go to Europe. Only 1.6% of the refugees interviewed considered leaving Istanbul for EU countries. But this does not mean that the situation is the same for all the Syrians living in Turkey. With a Syrian population of more than 500,000, Istanbul has recently become the new capital city of Syria, offering its refugee-origin inhabitants the opportunity to integrate so that they can relatively easily enjoy accommodation facilities, employment possibilities, schooling, health services, in-kind assistance, and several other services, without being stigmatized.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Bianca Kaiser for her invaluable remarks and suggestions. I am also grateful to Antoine Bailly for asking me to contribute to this issue. I also owe special thanks to the Science Academy Turkey and its President, Mehmet Ali Alpar, for making it possible for me to present my findings in the 28th Annual Meeting of the European Academy at Cardiff University on 29 June 2016.

Ayhan Kaya is Professor of Politics and Jean Monnet Chair of European Politics of Interculturalism at the Department of International Relations, Istanbul Bilgi University; Director of the Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence; and a member of the Science Academy, Turkey. He received his PhD and MA degrees at the University of Warwick, UK. Some of his latest books are Europeanization and Tolerance in Turkey: The Myth of Toleration (London: Palgrave, 2013); Islam, Migration and Integration: The Age of Securitization (London: Palgrave, 2012). Kaya received the Turkish Social Science Association Prize in 2003; the Turkish Academy of Sciences (TÜBA-GEBİP) Prize in 2005; the Sedat Simavi Research Prize in 2005; the Euroactiv-Turkey European Prize in 2008, the Prize for the best Text Book given by TÜBA; and the Prize for excellence in teaching at the Department of International Relations, Istanbul Bilgi University in 2013.