Introduction

In the twenty-first century, the gradual economization of foreign policy, stemming from growing economic interdependencies, can be observed. It encourages states and international organizations to use economic tools to achieve political goals, applying economic statecraft as defined by Baldwin: ‘influence attempts relying primarily on resources which have a reasonable semblance of a market price in terms of money’. Baldwin distinguishes the negative sanctions (penalties) from the positive ones (actual or promised rewards) (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1985, 13–14). Applying the liberal concept of relative gains, Long (Reference Long1996, 22–31) claims that in many cases incentives could be more effective than sanctions. For the benefactor (the donor), incentives may open new trade and investment opportunities that are also gainful for the recipient. Sanction, on the contrary, can have negative effects on both sides. It is worth emphasizing that public opinion will also more likely accept applying incentives because they are peaceful and have a cooperative potential. The non-coercive character of them is acceptable for the authorities of the beneficiary country: the compliance with the donor’s demands does not challenge their reputation.

Incentives are most often used for allies to make the target government adopt a certain policy ‘by the manipulation of costs and benefits they face’ (Elliot Reference Elliott2010). The incentives are usually conditional – the donor expects a certain behaviour of the recipient. The tools of economic incentives could be tariff reductions, direct purchasing, export and/or import subsidies, facilitated entry into the market and the institutions, development assistance, incentives for private investments, transfer of technology, concessional loans, debt reduction, and so on, or even the promise of their application (Kamiński Reference Kamiński2018, 71).

Against this background, this article aims to assess a set of Polish economic incentives as tools of foreign policy toward Ukraine. Their effectiveness is estimated on the assumption that, besides specific Polish initiatives, the inducements introduced by the EU were predominant. As an EU-member country, Poland also takes responsibility for, and shares the costs of, the EU’s economic and political support for Ukraine. This assessment applies the goal-driven criterion. The purposes will be determined on the basis of observations about specific events and decisions, relevant documents, and semi-structured interviews.

The intensification of the engagement with Ukraine became necessary when Russia annexed Crimea and became involved in the military conflict in Eastern Ukraine, trying to undermine the country’s cohesion. Russia wanted to weaken the pro-Western authorities that took power in Kyiv after the so-called Euromaidan (Averre Reference Averre2016, 699–725), so this article concentrates on the incentives applied after 2014.

EU Policy

EU policy toward Ukraine is crucial for Polish engagement. The prospect of integration in the EU was a strong incentive for Ukrainians to support the reforms required by EU via the Association Agreement (AA), including the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), offering Ukraine greater access to the EU market, which came into full force in September 2017. Signing the agreement, Ukraine pledged to carry out reforms in many fields. For the EU, the most important were those connected with decentralization, public administration, finances, and the judicial system (European Parliament 2017). The visa-free regime introduced in June 2017 definitely enhanced public support for integration with Europe.

In 2014, the EU earmarked €12.8 billion over the next few years for the major reforms. In fact, it donated over €15 billion in grants and loans until June 2019. All the EU projects for Ukraine are supported and co-financed by the member states, which, in addition to the above-mentioned sum, allocate funds on the basis of bilateral agreements and projects (EC 2019). EU officials counter the argument that the assistance is insufficient for Ukraine’s substantial needs. They claim that the Ukrainian absorption capacity for the funds is still low, mainly due to the bureaucratic obstacles that also block private investments (Jarábik et al. Reference Jarábik, Sasse, Shapovalova and De Waal2018).

Aims of Polish Policy toward Ukraine

One of the five fundamental issues of Polish Foreign Policy Strategy for 2017–2020 was ‘how to ensure the stability of Poland’s immediate neighbourhood’. It was declared that an active Eastern policy was indispensable to ensure security. This should involve supporting pro-European reforms by means of ‘ambitious cooperation instruments […] within the framework of an updated Eastern Partnership [EaP]’ (MFARP 2017b).

For Poland, cooperation with Ukraine is crucial for several interdependent reasons:

-

(1) A stable, democratic, and West-oriented Ukraine is vital for Polish security. Ukraine should also be independent from Russia in terms of politics and economy.

-

(2) Polish engagement in Ukraine is an element of the enhancement of Poland’s position in the EU, which can be gained by acting as a supporter of Ukraine’s integration with the West. Poland’s reputation as an expert may help realize its ambition to influence EU policy toward the East as the Polish contribution to EU’s common foreign policy.

-

(3) The perspective of opening a large market for Polish trade and investments should also be considered. A friendly Ukrainian government would be able to create stable conditions for the economic activities of Polish businesses.

-

(4) Poland wants to discourage Russia from the latter’s policy of Ukrainian destabilization and to curtail Russia’s ambition to exert its influence in Eastern Europe.

To achieve all these goals, Poland has adopted a long-term strategy aimed to build a stable state and ensure its influence on Ukraine’s foreign policy. Poland has no possibility to earmark significant financial resources for economic incentives besides its participation in the EU’s initiatives. Instead of large-scale programmes, though, the Polish government is able to provide assistance in undertaking the reforms in Ukraine.

The EU’s economic incentives for Ukraine are conditional. In the AA, the EU formulated its list of expected changes in Ukraine in exchange for the EU’s economic support (EUR-Lex 2014). The Polish assistance could be labelled as semi-conditional. The Polish authorities have not issued any official document that enumerates the requirements. Although certain reforms are expected, Poland does not exert excessive pressure, as the incentives are part of a long-term strategy. However, in terms of Polish foreign policy aims, the most important are decentralization, the reform of public finances, educational cooperation, and the fight against corruption (Interview#2, Interview#2a). Because of its multidimensional character, the assistance is coordinated by many agencies that also engage nongovernmental actors.

Inducements and Obstacles – the Political Context of Polish Policy toward Ukraine

Poland was the first state to recognize Ukraine’s independence on 2 December 1991. On 18 May 1992, the Treaty on Good Neighbourhood, Friendly Relations and Cooperation between the Republic of Poland and Ukraine was signed. Subsequently, numerous institutions tailored to strengthen Polish–Ukrainian relations were established (MFARP 2017a). The importance of friendly relations with Ukraine, promoted by the prominent Polish intellectual exile Jerzy Giedroyć, was recognized by all Polish governments after 1989. In May 2008, Poland and Sweden proposed the launch of the EaP in the framework of the European Neighbourhood Policy (Burlyuk Reference Burlyuk2017, 8–9).

That Ukraine ranks high on the list of Polish priorities also showed after Russian aggression. During the visit of a Polish delegation in Kyiv in January 2015, many important agreements were signed (PMO 2015). On 19 March 2015, the Office of the Government Plenipotentiary for Supporting Reforms in Ukraine was established. The Office’s tasks involved coordinating and monitoring all governmental activities in this area. It was also responsible for connecting Polish initiatives with those of the third-party countries, the EU, and international financial institutions, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the EBRD, the EIB, and the World Bank (Interview#1).

After the Polish elections of October 2015, the Law and Justice Party (LJP) formed the government. It introduced reforms in the law system. Some decisions made during this process were considered by the EU institutions as violations of the Polish constitution (European Parliament 2018). As the Polish government refused to yield to the EU’s major recommendations, Polish influence in EU weakened (Iwaniuk Reference Iwaniuk2017). Still, the main priorities of Polish policy remained the same. It was declared that Poland could afford sending experts to help Ukraine work out the plan for its reforms, derived from the Polish experience. The LJP pledged to a significant increase in the bilateral trade volume and to encourage Polish investments (PiS 2015).

At the same time, the two countries’ turbulent history from the Second World War became an important issue in their bilateral relations. In April 2015, the Ukrainian Parliament passed the law ‘On the Legal Status and Honoring of Fighters for Ukraine’s Independence in the Twentieth Century’ (UINM 2015). One of the fighters was Stepan Bandera, the co-founder of the military organization responsible for the Volhynia massacres (in 1943–1944, about 100,000 Polish civilians were murdered). In July 2016, the Polish Parliament enacted legislation to ‘pay homage to the victims of genocide perpetrated by the Ukrainian nationalists on the citizens of the Second Republic of Poland in 1943–1945’ (Sejm Reference Sejm2016). The Ukrainians in turn recalled retaliatory actions by Polish guerrillas killing Ukrainian civilians. All this caused tensions in bilateral relations, and hostile incidents were organized by nationalistic organizations in both Poland and Ukraine. This ‘historical policy’ may be harmful in the mutual perception of Polish and Ukrainian citizens (Koposov Reference Koposov2018, 202–203).

Development Aid – Crucial Set of Incentives

The main sources of Polish financing for development aid to Ukraine are the grants in the framework of the Polish Development Aid (Polska Pomoc Rozwojowa) of Foreign Affairs, notably by the Department of Development Cooperation. In the Polish Multiannual Development Cooperation Program 2016–2020, in Ukraine’s case, the component of enhancing good governance is aimed at public administration, the organizations of civil society, and the private sector. The Polish government wants to support the Ukrainian financial market’s stability, local government reforms, the eradication of corruption, and the encouragement of civil society’s engagement in the above-mentioned reforms. The projects are tailored to enhance the attractiveness of the Ukrainian market, mainly in terms of its stabilization and the formulation of clear rules for business operations. Polish experts provide support in implementing the necessary reforms.

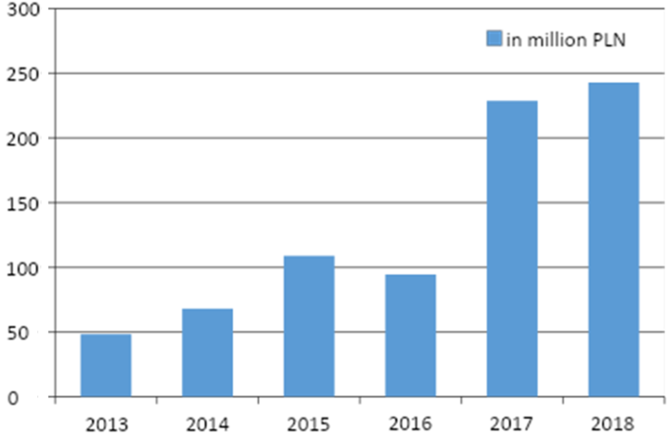

Polish non-governmental organizations (NGOs), local governments, and educational institutions receive the grants for these projects that are realized with the participation of the Polish central administration. Most projects are aimed at enhancing Ukrainian business and entrepreneurship (Polska Pomoc 2014). Starting in 2014, compared with other ‘priority countries’ for Polish Aid, activities in Ukraine have been among the largest grant receivers. After the conflict in Ukraine, a significant increase in the value of Polish development aid for this country can be observed (Figure 1).

An important area for Polish Aid is assistance in the development of the private sector. The internally displaced persons (people who had to change their residence but did not leave Ukraine) are supported, not only in terms of access to social services. The Polish government and the United Nations Development Programme also initiated a project to support opening small-scale start-up businesses. It encourages using innovative technologies and ensures access to education and training (UNDP 2017).

The Polish Ministry of Investment and Development implemented the project called ‘The Enhancement of the Competitiveness of Ukrainian Regions and the Development of Polish-Ukrainian Economic Cooperation’ with a budget of PLN 5.9 million for 2018–2020. Next to sharing know-how, financial support for small- and medium-sized enterprises and for Ukrainian high-technology start-ups was provided (MFiPR 2019). In addition to the economic gains for both sides, the project’s mission statement includes ‘the support of the building of [a] self-governing and democratic state,’ so the political aim is clearly visible. The project is realized mainly at the regional level and provides assistance to local Ukrainian authorities. As for supporting good governance, the experts often advise following the pattern of Polish reforms (Interview#3). This could have an impact on future Polish–Ukrainian relations; it might for example facilitate cross-border cooperation of local governments operating according to similar rules. The decentralization reform seems crucial in this context.

However, the budget for these purposes is limited. Development aid constitutes 0.14% of Polish GDP (for 2018), but according to EU obligations it should be 0.3% until 2030. Moreover, Poland does not have its own separate development agency, so it cannot acquire EU funds for this kind of activity. This also diminishes the opportunities for Polish firms participating in EU development projects (Interview#2, Interview#2a).

The Polish government perceived investing in the education of young people as ‘one of the best investments in the future’. Currently, Ukrainians account for nearly half of the foreign students in Poland. A wide variety of scholarships available for students from Ukraine is financed by the Polish government. In the academic year 2018–2019, over 39,000 persons from Ukraine studied in Poland, constituting by far the largest group of foreigners studying in this country. The number increases every year (Study in Poland 2019).

Investments and Trade

The Polish government supports companies operating in Ukraine mainly by the Foreign Trade Office, in the framework of the Polish Investment and Trade Agency (Polska Agencja Inwestycji i Handlu, PAIH). The investments in Ukraine are potentially rewarding for Polish citizens because of the size of the market, geographical proximity, as well as the similarities of language. The other advantageous factor is the low labour cost. The value of Polish investments in Ukraine is steadily changing: US$ 820 million in 2014, $708 million in 2015, $680 million in 2016, $509 million in 2017; at the end of 2018 it was US$ 593 million (State Statistics Service of Ukraine, UKRSTAT 2018). In 2018 the volume of Ukrainian investments in Poland was about US$ 7 million, a noteworthy drop in comparison to US$ 49 million in 2017. In other EU countries, this volume kept increasing (UKRSTAT 2018). Currently, the opportunities for Ukrainian investors in Europe are wider (Interview#4).

Significant increases in Polish investments in Ukraine in future will be determined by the country’s political and economic stability. For this reason, Polish development aid (as described above) is also a crucial incentive in this regard. This inference is confirmed by Polish investors in Ukraine: corruption, the lack of reliable law enforcement and of a law respecting property rights, and the conflict in the eastern part of the county still discourage investors (Drost Reference Drost2016).

One of the crucial conditions for a successful policy on incentives is the transfer of new technologies. This may occur through investments encouraged by the government. One example could be the renewable energy devices brought from Poland that are used in Zbarazh. The project ‘Good Energy School’, financed by Polish aid in 2017, was brought to life by the Polish NGO – Foundation INNOVATIS, with the Ternopil Regional Office of the Association of Ukrainian Cities. The project partner was the Polish company HEWALEX, which delivered the solar collectors and conducted the training for this technology. This investment also resulted in the launch of a continuing education programme for technicians in Ternopil Vocational College. At the same time, the project was profitable for the Polish company and added to the application of environment-friendly solutions, the encouragement of new entrepreneurship, and the improvement of energy efficiency in Zbarazh. The programme was continued in 2018. The Kyiv Vocational College is also included in the project, which is realized on the basis of Polish technologies and with the collaboration of Polish entrepreneurs active in the Ukrainian market (Interview#2).

According to the Polish Central Statistical Office, the value of Polish exports to Ukraine dropped by 27.1% in 2014, and the losses in 2015 were still visible (–5.3%). This disadvantageous tendency was reversed in 2016, with a 21% increase. However, a return of the export volume to the 2013 percentage occurred only in 2017. When compared with the first quarter of 2016, Polish exports to Ukraine in the first quarter of 2017 rose by 52.4% (PLN 4.4 billion), and imports increased by 30.1% (PLN 2.2 billion) (GUS 2017). In 2017, Poland became Ukraine’s second most important trade partner (after Germany in export of goods, after Italy in import of goods) among EU countries (Eurostat 2019). The reason for this dynamic upsurge was mainly the full implementation of the DCFTA in September 2017, which removed many barriers to mutual exchanges. Nonetheless, the Polish government’s role should not be neglected. Although not many direct tools were applied, such as export/import or investment subsidies, the indirect support should be noticed.

As Long (Reference Long1996, 79) claims, coordination of activities over the donor government’s agencies is crucial for the effectiveness of the incentives. In this context, the roles of three government units are worth mentioning. In 2016, the Export Credit Insurance Corporation Joint Stock Company (KUKE) significantly increased the year-on-year insurances guaranteed by the State Treasury (KUKE 2016). The Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego (BGK) supports the purchasers of Polish goods and services in the countries where access to the market is restricted and the risk of conducting business is significant. Ukraine falls into this group of countries. The BGK provides Ukrainian importers with loans that are cheaper than those in Ukraine, but a company’s creditworthiness is still considered. In fact, the bank assumes the risk of insolvency of the contractors of the Polish companies that receive immediate payment for the sold goods (Interview#4). In October 2019, BGK has concluded with a large Polish company a debt purchase agreement to finance exports to Ukraine for over €12 million (Interview#4a). The PAIH provides Polish businesses with information about the conditions of business activities, as well as about governmental assistance and promotion programmes. Many initiatives are available, such as conferences, business meetings, and trade fairs, with the participation of Polish and Ukrainian officials, as well as entrepreneurs from both countries. The majority of these initiatives are partly financed by the Polish government (Interview#5). All the interviewed experts from the above-mentioned agencies agreed about their close and smooth mutual cooperation but emphasized that their activities had no political character. In fact, they do not receive any suggestions from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

A barrier to the programme’s achieving more significant outcomes was the low interest by Ukrainian firms to benefit from it. At the same time, Polish entrepreneurs were waiting for the positive effects of Ukrainian reforms, which would improve the conditions for conducting business (Interview#4). In 2019, a significant change could be noticed. BGK has completed several large transactions on the Ukrainian market, and in 2020 it is working on further projects. A growing activity of Polish exporters on the Ukrainian market could be observed, as well as the use of export support instruments by BGK in relation to this market. A significant increase in interest in BGK’s offer among Ukrainian entrepreneurs was also noticeable, which probably results from information on completed transactions and promotional activities (Interview#4a). The Ukrainian economy takes advantage of these programmes, and the two countries’ interdependence grows. It brings Poland and Ukraine closer together and broadens the scope of their common interests.

As Long (Reference Long1996, 25) notes, public support for the incentives from the donor state can be diminished when the recipient is the competing producer of certain goods. In the case of Poland and Ukraine, the bone of contention may be the exchange of agricultural products. During the DCFTA’s negotiations with Ukraine, Poland insisted on the introduction of agricultural quotas, which delayed the agreement. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that during the vote on the EU–Ukraine AA at the Polish Parliament on 28 November 2014, 427 persons voted in favour and only one against (Burlyuk Reference Burlyuk2017, 8).

On 28 June 2017, the EU ambassadors authorized an agreement on temporary autonomous trade measures, in addition to those of the DCFTA, to support the introduction of economic reforms in Ukraine. This agreement was tailored to ease the access of Ukrainian agriculture products to the EU market, with additional import quotas at zero tariff (EC 2017). This decision caused anxiety among Polish farmers about the inflow of Ukrainian products to the Polish market. During the vote on the new EU legislation, the Polish representative abstained (EPL 2017); however, Poland still had to yield to this decision. It seems that even strong pressure by the agricultural lobby on the Polish government cannot lead to the introduction of protectionist measures because of EU common trade policy. Thus, the Polish government should be ready to incur the costs, also keeping in mind its foreign policy priority of support for Ukraine. In 2017, agricultural products remained at the top of the mutual exchange list (after electromechanical and chemical industries products) (Interview#6). It can be observed that discussions on the economic cost of Ukrainian integration with the EU for Poland do not really feature in the broader public debate. In the perception of the Polish authorities, the geopolitical threats seem larger than the remote prospect of Ukraine’s full membership in the EU (Burlyuk Reference Burlyuk2017, 7).

Energy

Ukraine used to rely on gas supplies from Russia, but these were cut off as Moscow decided to pursue its plan of building Nord Stream II (Gazprom would be the only owner). Russia declared that it would continue a ‘minimum level of supply’ after the transit agreement’s expiration in 2019. The Stockholm arbitration court obliged the Ukrainian state-owned gas firm, Naftogaz, to resume purchases from Russia until the end of the contract in 2019, after a two-year interruption. Despite this judgment, Gazprom has not started gas supplies to Ukraine again (Harper Reference Harper2018). But it would probably not be profitable for Russia to maintain the Ukrainian route of transit of gas to Europe after the completion of Nord Stream II. Poland objects to Nord Stream II as it would harm Ukraine and undermine the EU Energy Strategy. For this reason, a project on the construction of a 112 km pipeline between Ukraine and Poland was launched in 2016. The work was supposed to start in 2017. However, it has been delayed because the Ukrainian side is uncertain about whether the level of supply through Ukraine would be high enough to make the investment profitable. Besides, Poland has to build only about 2 km of pipeline, and Ukraine 110 km. That is why the project has stalled and there was no information about its future development at the time of writing of this article (March 2020) (Kadej Reference Kadej2019).

From August 2016 to December 2017, the Polish Oil and Gas Company (PGNiG) sent about 1 billion m3 of gas to Ukraine. This gas was produced in Poland at the liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in Świnoujście. The gas originated mainly from Qatar, Norway and the USA (Harper Reference Harper2018). The Świnoujście gas terminal is being extended and further contracts for the supply of American LNG are being signed, which will allow Poland to become independent of Russian supplies after the contract is completed in 2022. Poland offers cooperation and the possibility of selling gas from these alternative supplies to Ukraine. Poland has ambitions to become a Central European gas hub and to expand the Hermanowice-Bliche-Volytsia connection. This is an interesting perspective for Ukraine. However, one should consider the prices of gas, which may be cheaper on Western markets than American LNG. Poland can also benefit from cooperation with Ukraine. This country has large gas storage facilities, which may be offered to foreign partners and may be interesting for Poland. Poland is also considering continued export of electricity from Ukraine in the face of EU pressure to move away from its coal-based production (Świrski Reference Świrski2019).

Infrastructure and Transport

Another important area of cooperation is infrastructure improvement. For this purpose, the Polish government in 2015 granted a €100 million loan to Ukraine under preferential conditions. It was dedicated to a project that would modernize the road infrastructure of the borders between the two countries, as well as the construction of new border-crossing points. The Polish exporters and the Ukrainian entrepreneurs had to agree on contracts that fit the financing, with the value of Polish goods and services not less than 60% of the contract. The interest charged to this five-year credit was low at 0.15% (Sejm Reference Sejm2015). According to Bartosz Buraczyński from the Ministry of Finance, among the EU members, Poland is the most active partner in providing technical and consulting support in the process of adjusting Ukrainian legislation, procedures, and customs practices to the DCFTA standards (Interview#1).

Finance

During the Polish Prime Minister’s visit to Kyiv in January 2015, a declaration of financial cooperation between the respective Ministries of Finance of Poland and Ukraine was signed. In the framework of the programme, Study Tours to Poland, the leaders of the reforms of the Ukrainian local governments have the opportunity to obtain information about Polish experiences, the mechanisms of financing of local self-governments, and so on (Interview#1).

Another important action of the Polish government was an agreement on opening a swap currency line (zloty/hryvnia) to the amount of 4 billion zlotys by the Polish National Bank and the National Bank of Ukraine to improve the stability of Ukrainian finances in 2015. As the Polish zloty is a convertible currency, the swap line allowed Ukraine to exchange the zloty with the other currencies it needed (e.g. the euro or the US dollar). The setup was also profitable for Polish companies dealing with Ukraine as it enhanced the payment capacity of an important trade partner (Bninska Reference Bninska2015).

Ukrainian Workers in Poland

A unique incentive is the possibility of Ukrainians being employed in Poland. However, this has a double effect. On one hand, Ukrainians are able to earn incomes in Poland that are approximately five times higher than in Ukraine. It is also profitable for the Polish economy, with its significant need for additional labour. On the other hand, it is not profitable for the Ukrainian economy as the country started to suffer due to a lack of employees. However, according to the Central Bank of Ukraine, US$ 9.3 billion was sent back to Ukraine in 2017 through private transfers, outstripping foreign investments (Verbyany Reference Verbyany2018). In Poland, there are 1.5 million registered Ukrainians, and it is estimated that another 500,000 are undocumented. In 2015–2017 some 507,000 Ukrainians arrived in Poland (the first country of destination of migrants), and there has been an upward tendency after visa-free travel to the EU was issued (Krasnolutska and Verbyany Reference Krasnolutska and Verbyany2018). At the end of 2019 about 2 million Ukrainians lived in Poland (Kucharska Reference Kucharska2019).

The intensifying economic interdependence between Ukraine and Poland not only enhances their political links but also increases the demand for the services connected with all the bilateral transactions. Because of their experience and awareness of the specificity of the local market, the Ukrainian specialists could become particularly precious for the Polish businesses.

Evaluation of Ukrainian Reforms

Ukraine’s AA implementation agenda does not appear optimistic. According to the Ukrainian Centre for European Policy, only 11% of the legal provisions were fulfilled in 2017 (UCEP 2017). The 2019 report of the same organization is more optimistic: the authors underline that despite many difficulties, ‘Ukraine […] pursues root-and-branch reform of the state’ (UCEP 2019). The difficulties refer to the uncompleted administration reform, so that not all of the required changes can be effectively undertaken. Moreover, oligarchic monopolies remain strong, the economy is overregulated, and the rule of law is weak. As Konończuk et al. (Reference Konończuk, Cenuşa and Kakachia2017) argue, ‘no serious political force is able to successfully operate without financial backing from the oligarchs’. The oligarchs’ influence is a clear cause of the weakness of the state authorities and a serious disincentive for reforms, as oligarchs prefer to keep the state vulnerable to their pressures and take advantage of the systemic corruption.

On the other hand, successes can also be observed, such as a certain level of macroeconomic stabilization, reforms of the police and the Supreme Court, and the establishment of anticorruption agencies. In general, economic changes involving the abolition of energy arbitrage, the pension reform, and the banking reform are regarded positively. The major criticism targets the legal and the judicial reforms (EC 2019).

The EU incentives are conditional, so theoretically a negative evaluation could lead to the revocation of EU support, effectively changing economic incentives into economic sanctions. Considering that the Ukrainian authorities expect more financial support from Poland and the EU, such a situation could have disastrous political consequences. The Ukrainian pro-Western attitude could be reversed, and the country’s economy could deteriorate again. As Haass and O’Sullivan note, the incentives should entail the credible perspective of punishment for non-compliance. On the other hand, they also underline that expectations should not be too high, as a particular country’s unique conditions have to be taken into consideration (Haass and O’Sullivan Reference Haass, O’Sullivan, Haass and O’Sullivan2000, 176). Obviously, the EU and Poland have tried to exert pressure on the Kyiv government, but the results are bound to be limited (Interview#2) because of the complexity of the political situation in the country and also because of the country’s possibility to appeal to EU members eager to benefit from a newly opened market. The awareness that cooperation is profitable for both sides, in political and economic terms, inevitably weakens the conditionality of the incentives. The cited arguments also force us to distinguish the evaluation of the reforms from the evaluation of the effectiveness of the incentives. Therefore, the conditionality of the aid concerns only the support from the financial institutions (Interview#2a).

Effectiveness of the Incentives – Conclusion

In our attempt to gauge the effectiveness of the Polish economic incentives, we applied multiple variables, as proposed by Elliot, Blanchard and Ripsman, Haass and O’Sullivan, and Long. Such an assessment should also consider the context of Polish policy goals. Baldwin reasonably states that incentives may bring ‘neither perfect success nor perfect failure’ (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1985, 371). Still, the alternative scenario should always also be considered – what if Poland and the EU had not supported Ukraine? In evaluating the effectiveness of the incentives, then, we will distinguish between the goals that are completed and those that remain to be completed.

Haass and O’Sullivan point out that the strategies of the policy of engagement depend on several variables, such as the actors, the kinds of incentives, and the goals to be achieved (Haass and O’Sullivan Reference Haass, O’Sullivan, Haass and O’Sullivan2000, 174). Poland as a long-term advocate of the Ukrainian case had been well prepared to apply economic incentives. This is an important factor: the recipient has to perceive the donor as a friendly state that will not jeopardize the recipient’s autonomy (Long Reference Long1996, 88).

When the donor aims at building a democratic society and promotes reforms, society-addressed incentives are logical and justified. The Polish incentives were principally based on development aid programmes that aimed to support reforms and enhance the Ukrainian private economic sector, and that helped create a friendly environment for business and political rapprochement. Educational initiatives are also particularly important and aligned with the vital goal of the Polish engagement to build friendly relations between the two states.

In assessing the effectiveness of economic statecraft, Blanchard and Ripsman assume that researchers should primarily take into account the political interests of decision-makers, as well as international and internal factors that affect the transformation of the external economic stimulus for political change. The authors also propose the category of stateness, meaning the government’s autonomy, capacity to manage the state, and legitimacy, which have a decisive impact on the government’s ability to react on the incentives (Blanchard and Ripsman Reference Blanchard and Ripsman2013, 16–17). Haass and O’Sullivan claim that authoritarian regimes or states where power is centralized are more susceptible to incentives because they usually have control over the economy and can make binding decisions as to the fulfilment of the donor’s requirements (Haass and O’Sullivan Reference Haass, O’Sullivan, Haass and O’Sullivan2000, 172–173). The Ukrainian government cannot be labelled authoritarian; powerful interest groups play a significant role in the political process, and the country holds democratic elections. In addition, the Ukrainian government does not control a large part of its territory due to the ongoing conflict in the eastern part of the country. All these factors constitute serious hurdles to the reforms.

In this context, two other variables should be considered – domestic policy and the cost of yielding to the donor’s requirements. The recipient government is usually determined to maintain its power, so if a particular demand might cause the discontent of society or of influential interest groups, a decision would be difficult to make unless the incentive was really desirable and/or the profits from it could be distributed. As the outcomes are usually long term, the government should be stable enough to maintain the required policy and convince its citizens about its being in the national interest (Haass and O’Sullivan Reference Haass, O’Sullivan, Haass and O’Sullivan2000, 174). Therefore, the incentives can be evaluated as successful not only when the donor’s aims are achieved but also when the process of their fulfilment heads toward the outcomes desired by the donor. In the case of Polish and EU incentives for Ukraine, the benefits for the target are obvious. In 2017, the Ukrainian economy grew by 2.5%, and inflation was at 14% (Jarábik and De Waal Reference Jarábik and De Waal2018). As the required reforms neglect to address social security issues, though, the population at large may have been disappointed in what they perceived as a lack of improvement in their standard of living. According to a December 2017 poll, 50% of Ukrainian citizens favoured EU integration (a minor drop from 59% in 2014), and 16% supported integration with the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). In June 2019, it was already 59% for the EU versus 19% for EAEU (International Republican Institute, IRI 2019). Increased support for integration with the EU may be linked to the fact that more people have seen improvements in the situation in their households. In December 2017, less than 6% of respondents noticed such a progress, while in June 2019 12% did (IRI 2019). This change may also have occurred due to expectations connected with the new authorities. The parliamentary and the presidential elections were held in 2019. The new President (Volodymyr Zelensky), Parliament and government of Ukraine have pledged themselves to continue implementation of the Association Agreement requirements. Their efforts have been recognized by the European Commission (EC 2019). Polish aid for Ukraine suffered no changes after the elections, functioning as it does in a multi-annual framework and the challenges in Ukraine have not altered. From 2021 on, Polish Aid will operate under a new development cooperation programme and plan, so priorities will be adapted to the needs of the Ukrainian side and to the progress of reforms in the areas where the Polish side will be able to share experiences (Interview#2a).

The possibility of the effectiveness of an incentive increases when it cannot be obtained from another source. Obviously, this suggestion applies to Ukraine – it cannot be self-sufficient, yet close cooperation with Russia is almost unthinkable in the foreseeable future. Next to political support, Ukraine needs development aid and a significant inflow of foreign investment to fulfil the conditions of the AA and to become independent from Russia. In this respect, again then, there seems to be no alternative to Ukraine’s Western turn. Poland could play a significant role in this process provided it keeps up its image as ‘advocate’ of Ukraine in the perception of both Ukraine and the EU institutions. It is worth mentioning that Poland’s unique experience in dealing with Ukraine has already been recognized and enlisted by other countries. For example, the German development agency (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit) asked Polish Aid’s support in the former’s actions connected with Ukrainian decentralization reform (Interview#2). Poland was also invited to cooperate on the reform of the vocational education and training system in Ukraine (Interview#2a).

Proper explanation of the national interest to its own public is also important for the donor country. Using its economic leverage is usually cost-consuming. Besides, some significant sources of economic power are beyond a democratic government’s control: it is crucial to ensure the cooperation of investors, traders, or NGOs (Haass and O’Sullivan Reference Haass, O’Sullivan, Haass and O’Sullivan2000, 177). Evaluation of this factor in the case of Polish policy results is ambiguous. On one hand, Poland’s successive governments have supported Ukraine. On the other hand, Polish public opinion about the Ukrainians has deteriorated significantly, notably when comparing the 2017 and the 2018 data published by the Centre of Public Opinion Research (Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej – CBOS). In February 2017, 36% of respondents had a positive opinion of Ukrainians, and 32% expressed the opposite opinion (CBOS 2017). In 2018, the figures were 24% and 40% (CBOS 2018) and in 2019 31% versus 41% (CBOS 2019). Support for an active Polish policy in Ukraine is not very significant. Even at the beginning of the 2014 crisis, only 12% of Polish respondents thought that Poland should be particularly engaged in support of pro-democratic reforms and the EU aspirations of Ukraine; it dropped to 6% in 2015. In 2015, 62% of the surveyed respondents were against Polish financial aid for Ukraine, whereas 31% supported this idea (CBOS 2015). Simultaneously, the Polish sense of insecurity with respect to its neighbour’s situation has been decreasing (CBOS 2016). According to Marek Kuberski, Deputy Director for development cooperation with the Eastern European countries, the Polish government’s engagement cannot yield to fluctuations in public opinion because in this case a crucial national interest is at stake. The divergences are eased by diplomatic activities (Interview#2). Besides, as van Bergeijk observes, ‘positive sanctions are less spectacular, because these rewards or incentives […] belong to the domain of silent diplomacy’ (van Bergeijk Reference Van Bergeijk1994, 20). The information is available on the websites of the particular ministries and agencies, but it is dispersed. Thus, it is not the topic of public debate.

The tools of planned economic statecraft should be carefully chosen to achieve certain goals. Poland’s main aims are to boost Ukraine’s democratic society and support the country’s administrative reforms, so the applied incentives seem to be properly tailored. Poland still acts within the EU framework as the supporter of maintaining its engagement. The two countries’ economic relations (notably the trade volume) are improving. Polish–Ukrainian relations are also enhanced by political, military, cultural, and educational cooperation. The message to Russia, boosted by EU economic sanctions, remains clear. With the support of EU and NATO, Poland has confirmed its commitment to discourage Moscow from exerting its influence in Eastern Europe. Russia still occupies Crimea and is engaged in Eastern Ukraine, but this situation may change in the course of time. Most importantly, Ukraine has the possibility to resist it.

About the Author

Paulina Matera is an Associate Professor at the University of Łódź (Chair of the Department of American Studies and Mass Media, Faculty of International and Political Studies). Her research interests are in the areas of contemporary international political and economic relations, and US foreign policy. She is an author of the books (in Polish): France in the Foreign Policy of the United States, The United States and Europe. Political and Economic Relations 1776–2004 (co-authored with Rafał Matera), The Impact of Economic Issues on the United States Policy toward Western Europe during the Presidency of Richard M. Nixon (1969–1974). She has authored several articles on the theory and practice of economic sanctions in the twenty-first century.