Introduction

Severe mental disorders – such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorders – have a negative impact not only on affected people but also on their family members, carers, and the society at large. Carers often play a central role in the process of patients’ referral to mental health services, in promoting the maintenance of regular contact of patients with those services, and in supporting patients’ adherence to prescribed treatments [Reference MacDonald, Ferrari, Fainman-Adelman and Iyer1–Reference Sunkel3]. Carers of people with bipolar disorder spend at least 3.9 h per day in their care, which increases to at least 5.7 h per day in carers of people with schizophrenia. Although the needs of carers of patients suffering from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or substance abuse disorders can be very diverse, they also face similar burdens in the taking care process. In fact, differences can be due to the specific type of illness, but also – in the case of addiction – to the abused substance (e.g., cannabinoids, opiates, and cocaine). It is also different if a person is suffering from comorbid severe mental illness and co-morbid substance use disorders because comorbidity poses an additional burden on both patients and family members [Reference Mihan, Mousavi, Khodaie Ardakani, Rezaei, Hosseinzadeh and Nazeri Astaneh4].

Carers often report high levels of objective (i.e., the time and finances devoted to care) and subjective burden (i.e., reduced quality of life, feelings of guilt, anger, anxiety, and stress). Many carers are often unable to work or have to take time off work to provide care. Up to two billion carers work up to 8 h per day with no remuneration, with unpaid care being equal to 5% of global gross domestic product. The indirect costs of caregiving account for $112.3 billion per year, representing the main source of costs for people with severe mental disorders [Reference Maj, van Os, De Hert, Gaebel, Galderisi and Green5–Reference McIntyre, Alda, Baldessarini, Bauer, Berk and Correll9].

To prevent or reduce the negative impact of burden on carers of people with severe mental disorders, several psychosocial interventions are available, including psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, counseling, and self-help groups [Reference Christensen, Kruse, Hellström and Eplov10–Reference Killaspy, Harvey, Brasier, Brophy, Ennals and Fletcher12]. There is a recognized need to support carers of people suffering from other non-communicable conditions, such as dementia [Reference Saadi, Carr, Fleischmann, Murray, Head and Steptoe13], and to address their needs by individualized interventions [Reference Fulford and Handa14, Reference Roe, Slade and Jones15]. The global dementia action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025 aims to achieve by 2025 the target of 75% of countries providing support for carers and families of people with dementia [16–Reference Stuart-Röhm, Clark and Baker20]. The implementation of the Action Plan includes delivering multisectorial interventions, including personalized psychosocial interventions for promoting the mental health and well-being of carers of people with dementia [21].

Based on this premise, the WHO has highlighted the need to provide guidance on effective psychosocial interventions to carers of people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorders, as part of the mhGAPMental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). The present systematic review and meta-analysis is intended to support the development of guidance on evidence-based psychosocial interventions for carers of people with severe mental disorders. The primary aim of our systematic review and meta-analysis is to assess the impact of psychosocial interventions for carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, or substance use disorders on the levels of carers’ subjective and objective burden, compared to standard care/usual care or other control conditions. Secondary outcomes include the effect of the psychosocial interventions on the levels of depressive symptoms, well-being/quality of life, sleep, skills/knowledge, self-efficacy, and physical health in carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder or substance use disorder.

Methods

The following keywords were entered in the databases of PubMed/Medline, EMBASE, PsychINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHIL, Scopus, African Index Medicus, Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Index Medicus for the South-East Asian Region, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, and Western Pacific Region Index Medicus: “psychosocial intervention(s),” “psychoeducation,” “cognitive-behavioral intervention(s),” “psychoeducational intervention(s),” “counselling,” “self-help,” “family member(s),” “carer(s),” “caregiver(s),” “sibling(s),” “parent(s),” “relative(s),” “spouse,” “mental disorder(s),” “schizophrenia,” “psychosis,” “alcohol use disorder(s),” “drug use disorder(s),” “severe mental illness,” “bipolar disorder,” and “family interventions.” Furthermore, repositories of systematic review protocols – including PROSPERO, Open Science Framework (OSF), and Cochrane – were searched using the same keywords. Only articles written in English were included.

The search strategy was limited to the period from 2015 to 2023 since earlier studies had been already covered in a previous systematic review [Reference Yesufu-Udechuku, Harrison, Mayo-Wilson, Young, Woodhams and Shiers22]. Studies identified in the previous review have also been considered in the present systematic review. The AMSTAR tool was used to assess the quality of that systematic review, and the evaluation report is available in the Supplementary Material of the present paper [Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel and Moran23].

Two researchers independently extracted the information regarding design, sample characteristics, and type of intervention for each selected study. The quality and level of evidence of each study were independently assessed by two researchers using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for quantitative studies [Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter and Alonso-Coello24], and the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tool for qualitative research [Reference Long, French and Brooks25]. The GRADE approach uses a structured method for assessing the overall study quality for each outcome by one of four ratings (high, moderate, low, and very low level of certainty) based on an evaluation of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, and imprecision.

Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.2 for Windows. For continuous outcomes, standardized mean differences (SMDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. When studies reported data in multiple formats, SMD and its standard error were calculated before entering data in RevMan. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by assessing X 2 value and by calculating the I 2 statistic, which describes the percentage of observed heterogeneity that would not be expected by chance. If X 2 was less than 0.05 and I 2 ≥ 60%, we considered heterogeneity to be substantial. Researchers independently assessed the studies against these criteria and resolved any discrepancy through discussion.

The following criteria have been considered: (1) carers were defined as relatives or friends who provide informal and regular care/support to someone with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or substance use disorders; (2) interventions were considered if they were provided to the carer of patients suffering from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or substance use disorders; (3) primary outcomes included subjective or objective burden; and (4) secondary outcomes included quality of life, depressive symptoms and/or well-being, sleep, skills/knowledge, self-efficacy, chronic stress (e.g., measured by cortisol levels), and physical health.

Papers were excluded when benefits of psychosocial interventions were reported for the person suffering from severe mental illness, without any data on the carer. Studies focusing on carers of persons suffering from other mental disorders were excluded.

The following study designs were included: case/control study, pre/post studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Non-original research, such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and narrative reviews, was excluded.

Results

Overview of the included studies

The selection process of the included studies has been reported in Figure 1. Overall, 14,510 studies were retrieved from the electronic search. Of these, 9,316 were duplicates and were subsequently excluded. Of the remaining 5,194 studies, 234 full-text articles were analyzed for potential inclusion in the review. Sixteen additional papers were added based on the previous review by Yesufu-Udechuku et al. [Reference Yesufu-Udechuku, Harrison, Mayo-Wilson, Young, Woodhams and Shiers22]. One hundred and eighty-eight papers were excluded due to non-relevant samples or outcomes, or because they were duplicated. Sixty-four studies were finally included.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

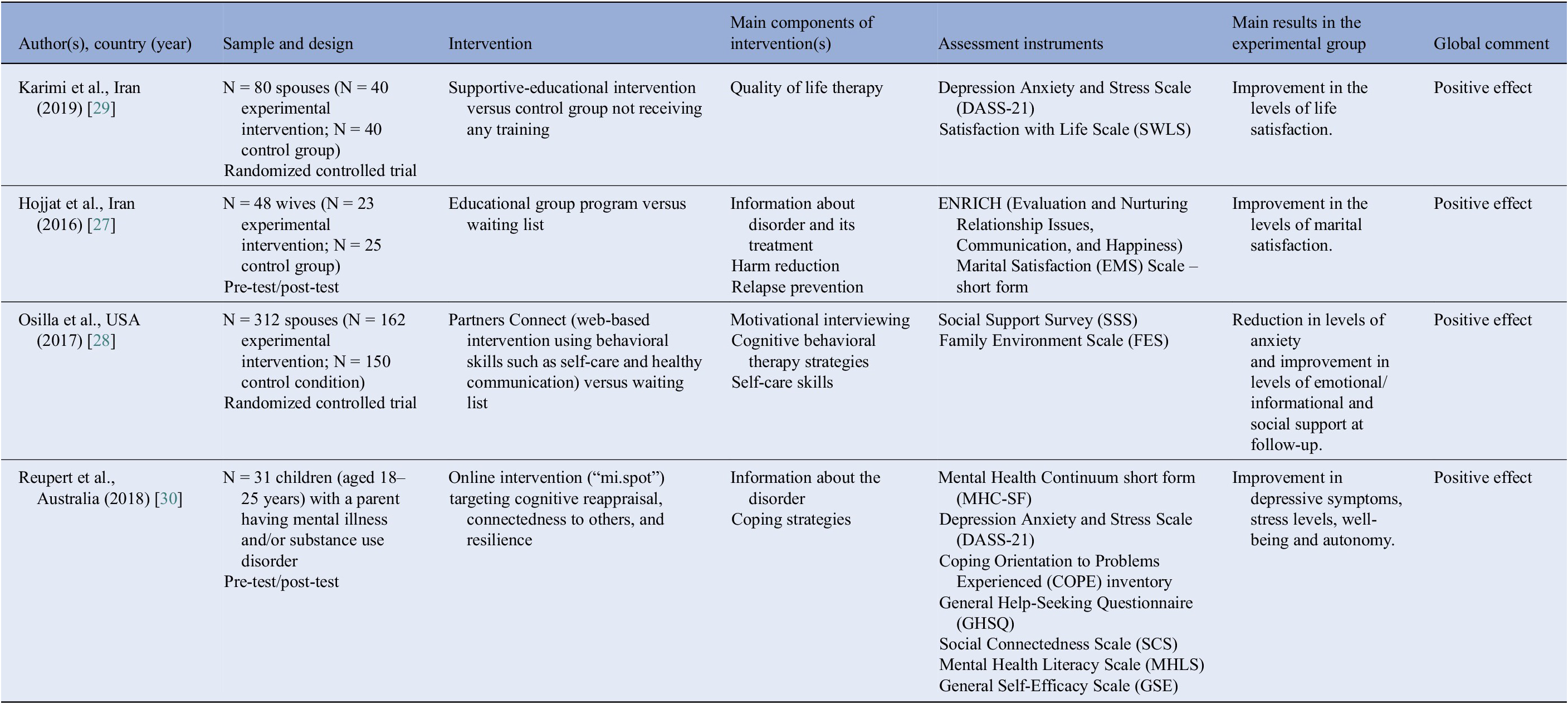

Interventions for carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder were conducted in 18 countries, most frequently in Hong Kong (n = 8), Australia (n = 7), India (n = 5), and the UK (n = 4). Interventions for carers of persons with bipolar disorder were conducted in 12 countries, mainly Italy (n = 3), Spain (n = 2), Australia (n = 2) and the US (n = 2). Two out of four studies on carers of persons with substance use disorders were carried out in Iran, and the other two in the US and Australia, respectively.

The most frequently adopted study design was RCT (n = 48 studies; 72.7%), particularly for studies dealing with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder (n = 34; 72.3%) and bipolar disorder (n = 12; 80%). Two studies (50%) on carers of persons with substance use disorders were RCTs.

Psychoeducation – defined as a psychosocial intervention with systematic and structured knowledge transfer about an illness and its treatment, integrating emotional and motivational aspects to enable carers to cope with the illness and to improve patients’ treatment adherence – was included in 38 studies on carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder, and in 14 studies on carers of persons with bipolar disorder. Psychoeducation was not used in any of the identified studies on carers of persons with a substance use disorder.

Almost all studies did not adopt rigid inclusion criteria regarding the relationship between carers and patients. The study by Koolaee and Etemdai [Reference Koolaee and Etemadi26] included only the mothers of patients with schizophrenia. The studies on carers of persons with substance use disorders were limited to patients’ wives [Reference Hojjat, Rezaei, Hatami and Norozi Khalili27], spouses [Reference Osilla, Trail, Pedersen, Gore, Tolpadi and Rodriguez28, Reference Karimi, Rezaee, Shakiba and Navidian29] or children [Reference Reupert, Maybery, Bartholomew, Cuff, Foster and Matar30].

The outcome measures most frequently considered in the various studies involved family burden (e.g., the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale, ZCBS; the Family Assessment Device, FAD); carers’ coping strategies (e.g., the Family Coping Questionnaire, FCQ; the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced, COPE); quality of life (e.g., the WHO-QOL-BREF; the WHOQOL-100); well-being (e.g., the Carer Wellbeing and Support, CWS; the Experience of Caregiving Inventory, ECI); and levels of knowledge (e.g., the Knowledge About Schizophrenia Interview, KASI; the Illness Perception Questionnaire for Schizophrenia-Relatives, IPQS-R; the Mental Health Literacy Scale, MHLS; the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire, Brief IPQ).

In the majority of the included studies (n = 56, 84.8%), a significant positive effect of interventions on outcome measures was found. Three studies on carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder [Reference Posner, Wilson, Kral, Lander and McIlwraith31–Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa33], and one study on carers of persons with bipolar disorder [Reference Reinares, Vieta, Colom, Martínez-Arán, Torrent and Comes34], found a modest positive effect. A positive effect of the interventions was not found in three studies on carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder [Reference Day, Starbuck and Petrakis35–Reference Shiraishi, Watanabe, Katsuki, Sakaguchi and Akechi37], and in three studies on carers of persons with bipolar disorder [Reference de Souza, da Silva, Molina, Jansen, de Lima Ferreira and Kelbert38–Reference Seyyedi Nasooh Abad, Vaghee and Aemmi40].

Studies on carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder

Forty-five studies on carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder were identified (Table 1).

Table 1. Studies on carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder (n = 45)

The studies were conducted most frequently in Hong Kong [Reference Chien and Chan41–Reference Zhou, Chiu, Lo, Lo, Wong and Luk48], Australia [Reference Szmukler, Herrman, Colusa, Benson and Bloch32, Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa33, Reference Day, Starbuck and Petrakis35, Reference McCann, Lubman, Cotton, Murphy, Crisp and Catania49–Reference McCann, Cotton and Lubman52], and the UK [Reference Smith and Birchwood53–Reference Lobban, Akers, Appelbe, Chapman, Collinge and Dodd56].

The majority of studies adopted an RCT design. Eight studies [Reference Smith and Birchwood30, Reference Day, Starbuck and Petrakis35, Reference Gleeson, Lederman, Koval, Wadley, Bendall and Cotton51, Reference Kordas, Kokodyńska, Kurtyka, Sikorska, Walczewski and Bogacz57–Reference Lobban, Akers, Appelbe, Chapman, Collinge and Dodd61] used a pre-test/post-test design, and one study adopted a non-equivalent control group design [Reference Chou, Liu and Chu62].

The samples mostly consisted of carers of persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Four studies [Reference Chien, Yip, Liu and McMaster44–Reference Chien, Bressington, Lubman and Karatzias46, Reference Lobban, Glentworth, Chapman, Wainwright, Postlethwaite and Dunn55] included carers of persons with recent onset of psychosis; seven recruited carers of persons with first-episode psychosis [Reference Day, Starbuck and Petrakis35, Reference So, Chen, Wong, Hung, Chung and Ng43, Reference McCann, Lubman, Cotton, Murphy, Crisp and Catania49, Reference Gleeson, Lederman, Koval, Wadley, Bendall and Cotton51, Reference McCann, Cotton and Lubman52, Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulos, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King54, Reference Öksüz, Karaca, Özaltın and Ateş63]; and one included carers of persons with either recent onset or chronic psychosis [Reference Shiraishi, Watanabe, Katsuki, Sakaguchi and Akechi37]. The study by Deane et al. [Reference Deane, Marshall, Crowe, White and Kavanagh50] included carers of persons affected by psychosis, without any further specification. The study by Lobban et al. [Reference Lobban, Akers, Appelbe, Chapman, Collinge and Dodd56] included carers of persons with either psychosis or bipolar disorder.

Ten studies [Reference Szmukler, Herrman, Colusa, Benson and Bloch32, Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa33, Reference So, Chen, Wong, Hung, Chung and Ng43, Reference Chien, Yip, Liu and McMaster44, Reference Chien, Bressington, Lubman and Karatzias46–Reference Deane, Marshall, Crowe, White and Kavanagh50, Reference Smeerdijk, Keet, van Raaij, Koeter, Linszen and de Haan64] used the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI), and five studies [Reference Hamza, Jagannathan, Hegde, Katla, Bhide and Thirthallli36, Reference Friedman-Yakoobian, Giuliano, Goff and Seidman59, Reference de Mamani and Suro65–Reference Kumar, Nischal, Dalal, Varma, Agarwal and Tripathi67] the Burden Assessment Schedule (BAS). Only four studies [Reference Day, Starbuck and Petrakis35, Reference Kordas, Kokodyńska, Kurtyka, Sikorska, Walczewski and Bogacz57, Reference Gutiérrez-Maldonado and Caqueo-Urízar68, Reference Ngoc, Weiss and Trung69] used ad-hoc assessment tools, specifically developed for the purposes of the study.

The majority of studies implemented a psychoeducational program/approach. Five studies [Reference Hamza, Jagannathan, Hegde, Katla, Bhide and Thirthallli36, Reference Chien, Yip, Liu and McMaster44, Reference Chien, Bressington and Chan45, Reference McCann, Cotton and Lubman52, Reference Lobban, Glentworth, Chapman, Wainwright, Postlethwaite and Dunn55] used a self-help intervention; two studies implemented a mutual support group approach [Reference Chien and Chan41, Reference Chou, Liu and Chu62]; and one used bibliotherapy [Reference McCann, Lubman, Cotton, Murphy, Crisp and Catania49]. Almost all studies reported a positive effect on considered outcomes. Three studies [Reference Posner, Wilson, Kral, Lander and McIlwraith31–Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa33] found a modest positive effect, and three [Reference Day, Starbuck and Petrakis35–Reference Shiraishi, Watanabe, Katsuki, Sakaguchi and Akechi37] found no positive effect of the experimental intervention (Table 1).

Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on primary and secondary outcomes in carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder

In the overall group of carers of persons with schizophrenia receiving any psychosocial intervention, there was an improvement in the levels of personal burden (standardized mean difference, SMD: –0.61, 95% CI: –0.86 to –0.36, p < 0.005), in well-being/quality of life (SMD: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.39 to 1.05, p < 0.005) and in the levels of knowledge about the disorder (SMD: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.20 to 1.01, p < 0.005) and self-efficacy (SMD: 1.15, 95% CI: 6.16 to 8.46, p < 0.005; Table 3).

Table 2. GRADE table for psychosocial interventions compared to treatment as usual, usual psychiatric care, or waiting list for carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder

CI, confidence interval; SMD, standardized mean difference.

a Severe, unexplained, heterogeneity (I 2 ≥ 60% or X2 < 0.05).

b Wide CI crossing the line of no effect.

c Less than 400 participants.

Bold characters indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Table 3. Studies on carers of persons with bipolar disorder (n = 15)

Risk of bias was rated as serious only for studies considering self-efficacy as outcome measure. For the remaining outcomes (i.e., personal burden, well-being/quality of life, depressive symptoms, knowledge about the disorder, and skills/coping skills) risk of bias was not serious. Inconsistency was rated as serious for all considered outcomes, while indirectness was not serious for any of them. Imprecision was rated as serious for studies considering depressive symptoms, knowledge about the disorder, skills/coping skills, and self-efficacy as outcome measures (see Table 2). Certainty of evidence was rated as moderate for studies considering personal burden and well-being/quality of life as outcome measures; low for studies considering depressive symptoms, knowledge about the disorder, and skills/coping skills as outcome measures; and very low for studies considering self-efficacy as outcome measure.

Subgroup analysis on efficacy of psychosocial interventions on carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder

A subgroup analysis based on the type of psychosocial intervention included in the different studies was performed (see Supplementary Table 1). A definition of the included approaches is provided in Appendix 1. Psychoeducational intervention was significantly associated with an improvement in the levels of personal burden (SMD: –0.70, 95% CI: –1.01 to –0.40, p < 0.005), well-being (SMD: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.39 to 1.54, p < 0.005) and knowledge about the illness (SMD: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.2 to 1.01, p < 0.005). Supportive-educational intervention was significantly associated with an improvement in personal burden (SMD: –0.26, 95% CI: –0.67 to –0.14, p < 0.005), but not with other considered outcomes. The remaining types of interventions were not associated with a statistically significant improvement in considered outcomes.

Studies on carers of persons with bipolar disorder

Fifteen studies on carers of persons with bipolar disorder were identified (Table 3), which were carried out mainly in Italy [Reference Fiorillo, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Sampogna, De Rosa and Malangone70–Reference Sampogna, Luciano, Del Vecchio, Malangone, De Rosa and Giallonardo72], Australia [Reference Reupert, Maybery, Bartholomew, Cuff, Foster and Matar30, Reference Hubbard, McEvoy, Smith and Kane73], and the US [Reference O’Donnell, Weintraub, Ellis, Axelson, Kowatch and Schneck39, Reference Perlick, Jackson, Grier, Huntington, Aronson and Luo74].

The majority of studies used an RCT design. Three studies [Reference Reupert, Maybery, Bartholomew, Cuff, Foster and Matar30, Reference Gex-Fabry, Cuénoud, Stauffer-Corminboeuf, Aillon, Perroud and Aubry75, Reference Zyto, Jabben, Schulte, Regeer, Goossens and Kupka76] adopted a pre-test/post-test design. Ad-hoc assessment tools were used only in the study by Hubbard et al. [Reference Hubbard, McEvoy, Smith and Kane73], while the other studies adopted very different assessment tools (Table 3).

One study included carers of persons with either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder [Reference Lobban, Akers, Appelbe, Chapman, Collinge and Dodd56], and is therefore included in both Tables 1 and 2. One study included carers of persons with either bipolar disorder or substance use disorder [Reference Reupert, Maybery, Bartholomew, Cuff, Foster and Matar30], and is therefore included in both Tables 2 and 3.

A psychoeducational program was implemented in 11 studies, either as a single-family [Reference Fiorillo, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Sampogna, De Rosa and Malangone70–Reference Sampogna, Luciano, Del Vecchio, Malangone, De Rosa and Giallonardo72] or as a group approach [Reference Stuart-Röhm, Clark and Baker20, Reference Gex-Fabry, Cuénoud, Stauffer-Corminboeuf, Aillon, Perroud and Aubry75]. All studies except one [Reference de Souza, da Silva, Molina, Jansen, de Lima Ferreira and Kelbert38] reported a positive effect of the intervention on considered outcomes (i.e., improvement of levels of burden, self-efficacy, and/or quality of life).

Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on primary and secondary outcomes in carers of persons with bipolar disorder

In the overall group of carers of persons with bipolar disorder receiving a psychosocial intervention, there was an improvement in the levels of personal burden (SMD: –1.15, 95% CI: –2.0 to –0.3, p < 0.005) and depressive symptoms (SMD: 3.70, 95% CI: 6.95 to 0.45, p < 0.005; Table 4). Risk of bias and indirectness were rated as not serious for all included outcomes. Inconsistency was rated as serious for all outcome measures. Imprecision was rated as serious for studies on well-being/quality of life, depressive symptoms, knowledge about the disorder, skills/coping skills, and self-efficacy (see Table 4). Certainty of evidence was rated as moderate for studies considering personal burden as outcome measure; low for studies considering depressive symptoms, knowledge about the disorder, skills/coping skills, and self-efficacy as outcome measures.

Table 4. GRADE table for psychosocial interventions compared to treatment as usual, usual psychiatric care, or waiting list for carers of persons with bipolar disorder

CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardized mean difference.

a Severe, unexplained, heterogeneity (I 2 ≥ 60% or X2 < 0.05).

b Wide CI crossing the line of no effect.

c Less than 400 participants.

Bold characters indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Subgroup analysis on efficacy of psychosocial interventions on carers of persons with bipolar disorder

A subgroup analysis based on the type of psychosocial intervention included in the different studies was performed (see Supplementary Table 2). Psychoeducational intervention was significantly associated with an improvement in the levels of personal burden (SMD: –0.63, 95% CI: –1.31 to –0.06, p < 0.005) and depressive symptoms (SMD: –3.70, 95% CI: –6.95 to –0.45, p < 0.005). Family-led supportive interventions were associated with an improvement in the levels of family burden (SMD: –4.03, 95% CI: 5.11 to 2.95, p < 0.005). Family-focused intervention and online “mi.spot” intervention were associated with a significant reduction in the levels of depressive symptoms (family-focused intervention, SMD: –5.46, 95% CI: –6.85 to 4.07, p < 0.005; “mi.spot,” SMD: –4.58, 95% CI: –10.40 to –1.24, p < 0.005). The remaining types of interventions were not associated with a statistically significant improvement in assessed outcomes.

Studies on carers of persons with substance use disorders

Four studies on carers of persons with substance use disorders were identified. All details are reported in Table 5. The studies were RCTs [Reference Hojjat, Rezaei, Hatami and Norozi Khalili27, Reference Karimi, Rezaee, Shakiba and Navidian29] or pre-test/post-test trials [Reference Hojjat, Rezaei, Hatami and Norozi Khalili27, Reference Reupert, Maybery, Bartholomew, Cuff, Foster and Matar30]. All studies adopted validated assessment tools. One study included carers of persons with both bipolar disorder or substance use disorder [Reference Reupert, Maybery, Bartholomew, Cuff, Foster and Matar30], and is therefore included in both Tables 3 and 5. Two studies [Reference Hojjat, Rezaei, Hatami and Norozi Khalili27, Reference Karimi, Rezaee, Shakiba and Navidian29] adopted an educational/informative approach.

Table 5. Studies on carers of persons with substance use disorder (n = 4)

Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on primary and secondary outcomes in carers of persons with bipolar disorder

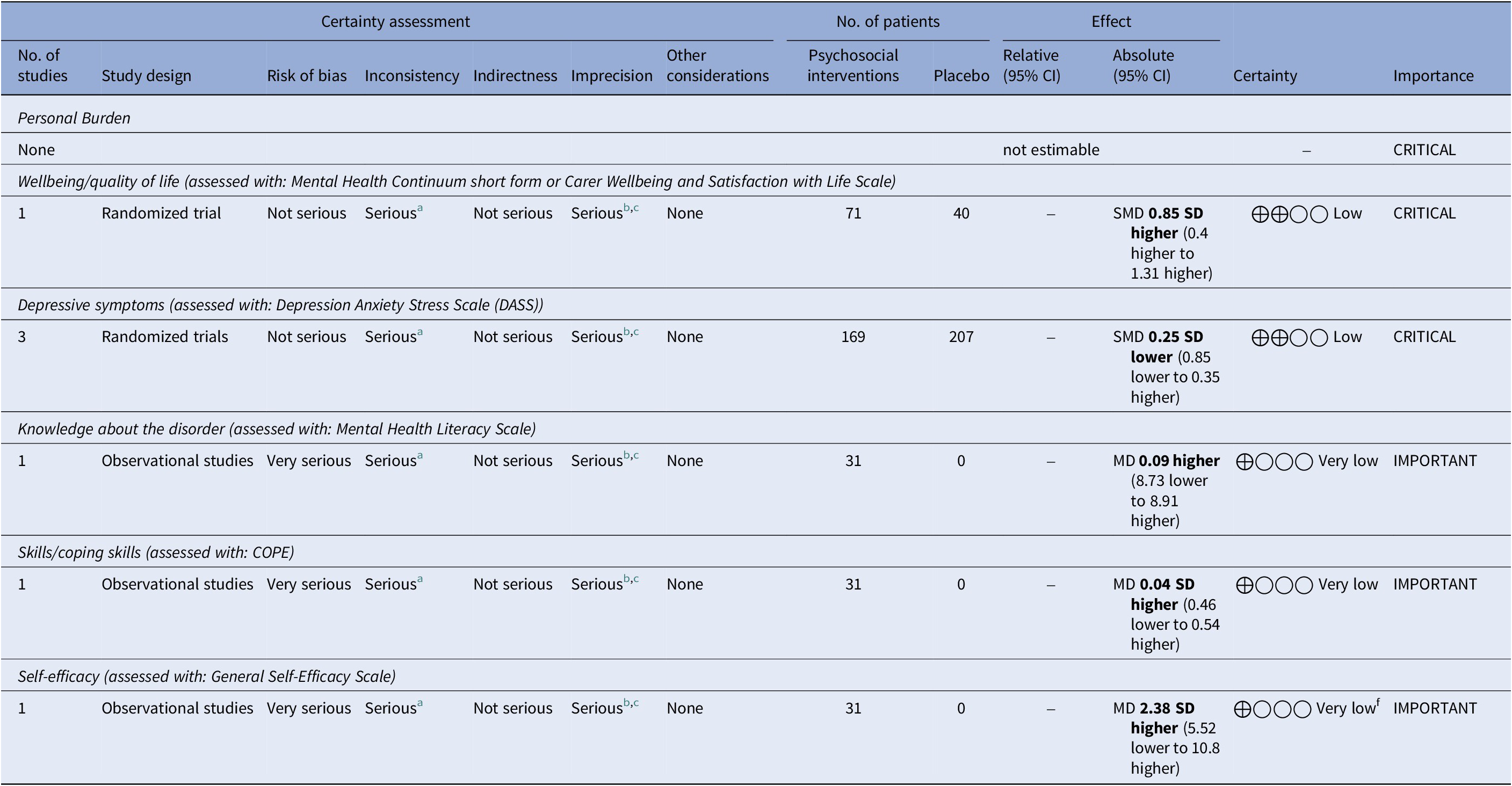

In the overall group of carers of persons with substance use disorder receiving any psychosocial intervention, there was an improvement in the levels of well-being (SMD: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.40 to 1.31, p < 0.005; Table 6). Risk of bias was not serious for studies including well-being/quality of life and depressive symptoms as outcome measures, whereas it was rated as very serious for studies considering knowledge about the disorder, skills/coping skills, and self-efficacy. Inconsistency and indirectness were rated as serious for all outcome measures. Imprecision was rated as serious for all outcome measures (see Table 6). Certainty of evidence was rated as low for studies considering well-being/quality of life and depressive symptoms as outcome measures; and as very low for studies considering knowledge about the disorder, skills/coping skills, and self-efficacy as outcome measures. No data were available on levels of personal burden.

Table 6. GRADE table for psychosocial interventions compared to treatment as usual, usual psychiatric care, or waiting list for carers of persons with substance use disorders

CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SMD: standardized mean difference.

a Severe, unexplained, heterogeneity (I 2 ≥ 60% or X2 < 0.05).

b Wide CI crossing the line of no effect.

c Less than 400 participants.

Bold characters indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Subgroup analysis on efficacy of psychosocial interventions on carers of persons with substance use disorders

A subgroup analysis based on the type of psychosocial interventions included in the different studies was performed (see Supplementary Table 3). Due to the low number of trials available for carers of persons with substance use disorders, this analysis did not detect any statistically significant difference between the various psychosocial interventions.

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that several psychosocial interventions are effective in carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder and bipolar disorder, with a moderate to low level of certainty. In particular, in carers of persons with schizophrenia/psychosis/schizophrenia spectrum disorder, psychoeducational interventions are significantly associated with an improvement in personal burden, well-being, and knowledge about the illness; and a supportive-educational intervention with an improvement in personal burden. In carers of persons with bipolar disorder, a psychoeducational intervention is significantly associated with an improvement in personal burden and depressive symptoms; family-led supportive interventions with an improvement in family burden; family-focused intervention and online “mi-spot” intervention with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms. Available studies focusing on carers of persons with substance use disorders found that psychosocial interventions used in this population are overall effective only on the level of well-being.

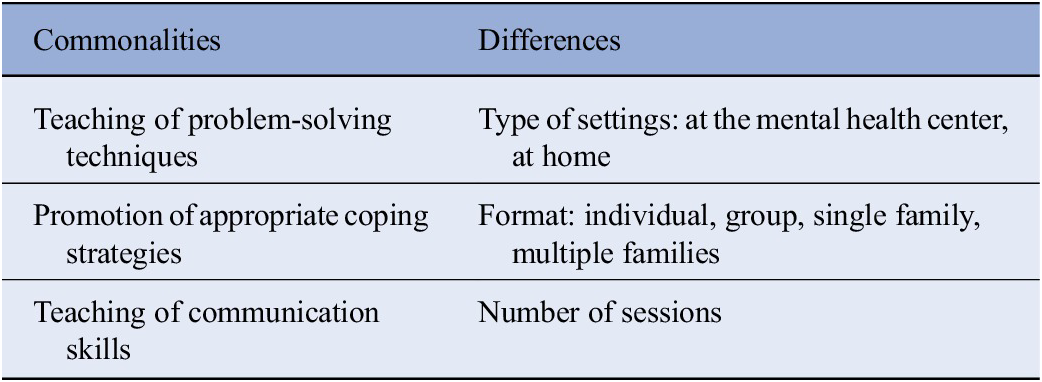

The psychoeducational approach is the most frequent intervention provided to carers of people with severe mental disorders, although different psychoeducational approaches exist. Common elements to the different approaches include the provision of problem-solving techniques [Reference Reinares, Vieta, Colom, Martínez-Arán, Torrent and Comes34, Reference O’Donnell, Weintraub, Ellis, Axelson, Kowatch and Schneck39, Reference Seyyedi Nasooh Abad, Vaghee and Aemmi40, Reference Chien, Yip, Liu and McMaster44–Reference Chien, Bressington, Lubman and Karatzias46, Reference McCann, Cotton and Lubman52, Reference Bulut, Arslantaş and Ferhan Dereboy58, Reference Friedman-Yakoobian, Giuliano, Goff and Seidman59, Reference Fiorillo, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Sampogna, De Rosa and Malangone70–Reference Gex-Fabry, Cuénoud, Stauffer-Corminboeuf, Aillon, Perroud and Aubry75, Reference Barbeito, Vega, Ruiz de Azúa, González-Ortega, Alberich and González-Pinto81, Reference Brown and Weisman de Mamani82, Reference Sharif, Shaygan and Mani100]; the promotion of appropriate coping strategies [Reference Stuart-Röhm, Clark and Baker20, Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter and Alonso-Coello24, Reference Reupert, Maybery, Bartholomew, Cuff, Foster and Matar30, Reference Reinares, Vieta, Colom, Martínez-Arán, Torrent and Comes34, Reference Cheng and Chan42, Reference Gleeson, Lederman, Koval, Wadley, Bendall and Cotton51, Reference Bulut, Arslantaş and Ferhan Dereboy58, Reference Amaresha, Kalmady, Joseph, Agarwal, Narayanaswamy and Venkatasubramanian66, Reference Kumar, Nischal, Dalal, Varma, Agarwal and Tripathi67, Reference Hubbard, McEvoy, Smith and Kane73, Reference Brown and Weisman de Mamani82, Reference Madigan, Egan, Brennan, Hill, Maguire and Horgan95, Reference Mubin, Riwanto, Soewadi, Sakti and Erawati96]; and the teaching of communication skills [Reference Gleeson, Lederman, Koval, Wadley, Bendall and Cotton51, Reference McCann, Cotton and Lubman52, Reference Kordas, Kokodyńska, Kurtyka, Sikorska, Walczewski and Bogacz57, Reference Bulut, Arslantaş and Ferhan Dereboy58, Reference Öksüz, Karaca, Özaltın and Ateş63, Reference Kumar, Nischal, Dalal, Varma, Agarwal and Tripathi67, Reference Ngoc, Weiss and Trung69, Reference Brown and Weisman de Mamani82, Reference Puspitosari, Wardaningsih and Nanwani97–Reference Sharma, Srivastava and Pathak99]. This intervention can be delivered in different settings (i.e., at the mental health center, at home), and format (individual vs. group; Table 7). The heterogeneity of the different psychoeducational approaches may represent a bias in the evaluation of their efficacy. In fact, differences include duration of the intervention, involvement of different mental health professionals, inclusion of the patients, etc. It has to be noted that short-term interventions, with an active involvement of users and carers in the provision of the intervention and the inclusion of booster sessions have been associated with higher levels of improvements of the considered outcomes. Another limitation of our review is that the majority of studies have been carried out in high-income countries, while only a few data are available from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Table 7. Core features of psychoeducational approaches

The dissemination of psychoeducation in ordinary routine practice is hampered by several obstacles, such as lack of training for health care professionals, lack of time for running the intervention, and lack of interest by carers [Reference Higgins, Murphy, Downes, Barry, Monahan and Hevey94]. Thus, research should focus on innovative strategies to promote the dissemination of psychoeducational interventions for carers of people with severe mental disorders on a larger scale, including web-based or app-based approach, such as the one included in the “mi.spot” intervention [Reference Yu, Xiao, Ullah, Meyer, Wang and Pot83]. However, few studies have been conducted so far in LMICs, highlighting the need to further promote the dissemination of such psychosocial interventions in those contexts [Reference Sharan84, Reference Xiang and Zhang85]. It should be that those psychosocial interventions need to be adapted to the socio-cultural context and to the limited resources of such countries, but their efficacy should not be impacted. However, further studies are needed and the mhGAP can be very important for supporting the dissemination of these interventions in LMIC settings [Reference Jones and Ventevogel77, Reference Silove86].

The evidence concerning the interventions for carers of people with substance use disorders is very limited, with only four detected studies. Carers of people with these disorders report specific needs in terms of emotional and practical support, which would deserve targeted investigation. Furthermore, the increasing prevalence of these disorders, in particular in the young population [Reference Klingberg, Judd and Sauce87], further highlights the need to develop supportive interventions for carers [Reference Arango, Dragioti, Solmi, Cortese, Domschke and Murray78, Reference Degenhardt, Stockings, Patton, Hall and Lynskey88].

Another encouraging finding is that online “mi-spot” intervention is effective in reducing levels of depressive symptoms in carers of patients with bipolar disorder, confirming the potential applicability and clinical utility of web-based and app-based interventions in the mental health field. In recent years, telepsychiatry and tele-mental health has witnessed an exponential growth, further nurtured by the COVID-19 pandemic and by the need to reduce in-person contact [Reference Torous, Bucci, Bell, Kessing, Faurholt-Jepsen and Whelan89, Reference Rauschenberg, Schick, Goetzl, Roehr, Riedel-Heller and Koppe90]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis on technology-based supportive intervention for carers of people with dementia has found that such approaches are beneficial for carers, especially in terms of increased accessibility overtime [Reference Scerbe, O’Connell, Astell, Morgan, Kosteniuk and Panyavin91]. However, digital interventions are still in their infancy regarding applicability as supportive interventions for carers of people with severe mental disorders, although these preliminary findings are encouraging [Reference Verduyn, Gugushvili and Kross79, Reference Wasil, Gillespie, Schell, Lorenzo-Luaces and DeRubeis80, Reference Espie, Firth and Torous92].

Furthermore, the majority of included studies (n = 48 studies; 72.7%) adopted a randomized controlled design, which represents the most rigorous methodological approach for experimental trials. However, some studies, especially those conducted in LMICs have been carried out using less rigorous methodologies, including pre-/post-evaluations (without control groups), small sample sizes with high attrition rates, using different outcome measures, and with different duration of the interventions (ranging from single session intervention to 6-month interventions). Of course, these methodological differences have been carefully taken into account when evaluating the global level of certainty of data. While the evidence from high-income countries is rather robust, there is the need to promote well-structured and rigorous studies in LMIC, to increase the quality of evidence.

Our study has some limitations. First, the quality of the evidence ranges from very low to moderate. For example, in studies on carers of people with schizophrenia, the risk of bias was rated as serious for several outcomes, such as the levels of knowledge or self-efficacy, being based on just one observational study. Moreover, the included studies are characterized by extreme heterogeneity, lack of precision, and small sample sizes, which might significantly affect statistical analyses. Another limitation is related to the type of considered outcomes, which are measured only using self-reported assessment tools, with a potential risk of response bias.

Carers of patients suffering from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorders report different clinical unmet needs and different types of objective and subjective burden, reflecting the clinical heterogeneity of such disorders. The decision to include these three diagnostic categories has been due to the need to update the mhGAP focusing on the most burdensome disorders for patients and their carers. Moreover, we have tried to overcome this possible bias by carrying out subgroup analysis on the different models of psychosocial interventions.

Conclusions

Our analysis confirms that several psychosocial interventions are effective in supporting carers of people with severe mental disorders. However, there is a need to collect more data of good quality, particularly in LMIC. Moreover, the efficacy and sustainability of those interventions should be evaluated in longer-term studies carried out in the real world.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.2472.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Appendix 1 – Description of psychosocial interventions

Brief Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management Program

The Brief Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management Program is a semi-structured program that was devised to allow the caregiver to gain awareness of various aspects of his or her daily life and distress due to caregiving responsibilities, as well as to assist the caregiver in developing stress management skills in a practical group environment. In this program, several aspects of other stress management programs, cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques, and resources for group psychotherapy are used. The approach has been manualized and consists of seven sessions.

Collective Narrative Therapy

Collective Narrative Therapy is a narrative group intervention, consisting of eight group sessions with different goals. All groups are facilitated by the same practitioner. The main topics are: creating relationship; describe, externalize and evaluate problems; understand and solve problems; reflect and make sense of experiences, and share positive communication; relax body and mind, and explore the meaning of life and inner strengths; and rewrite life stories and ascertain life goals.

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation is defined as a psychosocial intervention with systematic and structured knowledge transfer about an illness and its treatment, integrating emotional and motivational aspects to enable carers to cope with the illness and to improve patients’ treatment adherence. The content of psychoeducation interventions includes etiology of illness, treatment process, adverse effects of prescribed medications, coping strategies, coping skills training, problem-solving training.

Family-Focused Culturally-Informed Treatment model

The Family-Focused Culturally-Informed Treatment model is an individual or couple treatment for caregivers of persons with bipolar disorder. It is based on three premises supported by extensive research and theory: a) negative and dysfunctional automatic thoughts, feelings, and core beliefs about caregiving contribute to and sustain depressive symptoms and perceived burden among caregivers; b) depressive symptoms interfere with caregiver self-care and ability to manage the demands and stress associated with caregiving; c) the presence of caregiver’s depressive symptoms interferes with management of caregiving demands and impacts on severity of patient’s mood symptoms.

Family-Led Mutual Support Group program

The Family-Led Mutual Support Group program consists of 16 bi-weekly 2-h sessions co-led by two peer family caregivers. These caregivers are relatively more experienced in caregiving and are trained by the researchers to perform the peer leader role with a three full-day psychoeducation and supportive skills workshop. The workshop’s contents are structured in five stages, including engagement; awareness and addressing mutually shared psychosocial needs; managing common and individual physical and psychosocial needs of self and family members; taking up caregiving roles and demands and facing challenges; group termination.

All sessions place emphasis on supportive sharing of experience and information exchanges, problem-solving, and caregiving skill practices.

Yoga/Self-Help intervention

This consists of a self-help manual and DVD for practicing yoga intended for caregivers of patients with schizophrenia.

Supportive-Educational interventions

Supportive-Educational interventions consist of sessions aiming to improve levels of knowledge about the disorder, how to handle difficult behaviors, stress management, communication skills, and relapse prevention.

Online intervention (“mi.spot”)

“mi.spot” is an online, manualized intervention that targets young adults who have a parent with a mental illness and/or substance use disorder. The topics include: introduction to the intervention; information about mental disorders; assessing relationship with parents and/or other family members; managing stress; discussion on caring responsibilities; taking control of own life.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.