Introduction

According to social cognition theory, stigma is a multidimensional construct encompassing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral elements [Reference Corrigan and Shapiro1], and including the two dimensions of public stigma and self-stigma [Reference Corrigan2]. Public stigma reflects the attitudes and beliefs held by the general population and it could affect the daily interactions between the public and the individual suffering from mental disorders [Reference Corrigan3]. Self-stigma refers to the negative attitudes which those subjects turn against themselves, and it may have an effect on their personal experience with others and on their willingness to seek help [Reference Corrigan3–Reference Thornicroft6].

Stigma is probably one of the most important barriers to help-seeking and to personal recovery [Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko and Bezborodovs7,Reference Henderson, Noblett, Parke, Clement, Caffrey and Gale-Grant8]. Conversely, an inverse relationship has been found between stigmatizing attitudes and recovery orientation, in the sense that recovery oriented individuals may have less negative attitudes about people suffering from mental disorders [Reference Stacy and Rosenheck9]. Stigmatizing attitudes are widespread not only within health services in general but also in mental health facilities [Reference Ono, Satsumi, Kim, Iwadate, Moriyama and Nakane10–Reference Gabbidon, Farrelly, Hatch, Henderson, Williams and Bhugra14], with detrimental effects on the quality of health care received by the clients [Reference Henderson, Noblett, Parke, Clement, Caffrey and Gale-Grant8]. People suffering from mental disorders and/or substance use disorders have to face either an avoidant attitude by healthcare professionals [Reference van Boekel, Brouwers, van Weeghel and Garretsen15] or prejudices about their adherence to medications [Reference Corrigan, Mittal, Reaves, Haynes, Han and Morris16], and about the “psychological” nature of their physical symptoms [Reference Graber, Bergus, Dawson, Wood, Levy and Levin17]. Some studies have shown that mental health professionals may have more negative views than the general public on stereotypes, restriction of the individual’s rights, and social distance [Reference Jorm, Korten, Jacomb, Christensen and Henderson18,Reference Nordt, Rossler and Lauber19]. The frequencies of discrimination reported by respondents to surveys about stigma range from 17% [Reference Lasalvia, Zoppei, Van Bortel, Bonetto, Cristofalo and Wahlbeck20] to 31% [Reference Gabbidon, Farrelly, Hatch, Henderson, Williams and Bhugra14] in a physical health-care setting and from 16% [Reference Thornicroft, Wyllie, Thornicroft and Mehta13] to 44% [Reference Gabbidon, Farrelly, Hatch, Henderson, Williams and Bhugra14] in a mental health-care setting. Negative staff attitudes have been linked with reluctance to use mental health facilities [Reference Regier, Farmer, Rae, Myers, Kramer and Robins4–Reference Thornicroft6], poorer outcomes [Reference Gowdy, Carlson and Rapp21], and poorer customer’s satisfaction [Reference Garman, Corrigan and Morris22].

Professional burnout is considered as one of the most important factors explaining discrimination in mental health care [Reference Calicchia23,Reference Lauber, Nordt, Sartorius, Falcato and Rossler24], being common among mental health service providers and administrators [Reference Webster and Hackett25–Reference Awa, Plaumann and Walter28]. Maslach et al. [Reference Maslach, Schaufeli, Maslach and Marek29,Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter30] described burnout as a construct including three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA). The first refers to feelings of being depleted and fatigued, while DP refers to negative and cynical attitudes toward one’s work, and a reduced sense of PA (or efficacy) involves negative self-evaluation of overall job effectiveness [Reference Stalker and Harvey31].

Personality may also have a direct and moderating effect on generalized prejudice [Reference Arikan32,Reference Sibley and Duckitt33], since a significant negative relationships between some personality traits (i.e., openness and agreeableness) and prejudice has been found [Reference Ekehammar and Akrami34]. However, although the two concepts of prejudice and stigma may consistently overlap in their causes and consequences [Reference Phelan, Link and Dovidio35], a limited number of studies have explored a possible connection between personality and stigma in the proper sense [Reference Brown36–Reference Zaninotto, Rossi, Danieli, Frasson, Meneghetti and Zordan39].

The Five Factor model of personality [Reference Costa and McCrae40] argues that each individual has five basic personality traits, namely, openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability. Higher levels of openness are typical of individuals who are considered highly sensitive, imaginative, curious, and open-minded. Conscientiousness refers to subjects who are supposed to be careful, efficient, and self-disciplined, while extraverted individuals are characterized by gregariousness, assertiveness, and dispositions toward positive emotions. Agreeableness is usually associated to people who are perceived as kind, sympathetic, cooperative, and tactful, while emotional stability refers to the individual’s ability to remain emotionally stable and balanced in front of a potentially difficult or harmful situation [Reference McAdams41].

The current study aims to identify what path leads to stigma in a sample of mental health professionals, considering demographic and professional features, personality traits, and levels of burnout, by merging data-driven approach of network analysis [Reference Borsboom42–Reference Haslbeck and Fried44] and moderator analysis.

Methods

Study design, participants, measures, primary, and secondary outcomes

The present study was conducted between July 2015 and December 2017 within six Community Mental Health Services (CMHS) operating in North-East Italy. The sample explored in a previous study was further extended [Reference Zaninotto, Rossi, Danieli, Frasson, Meneghetti and Zordan39]. The study protocol was first approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Local Health Unit n. 8 (approval nr. 24091/8.2, 2015) and then extended to the other participating centers.

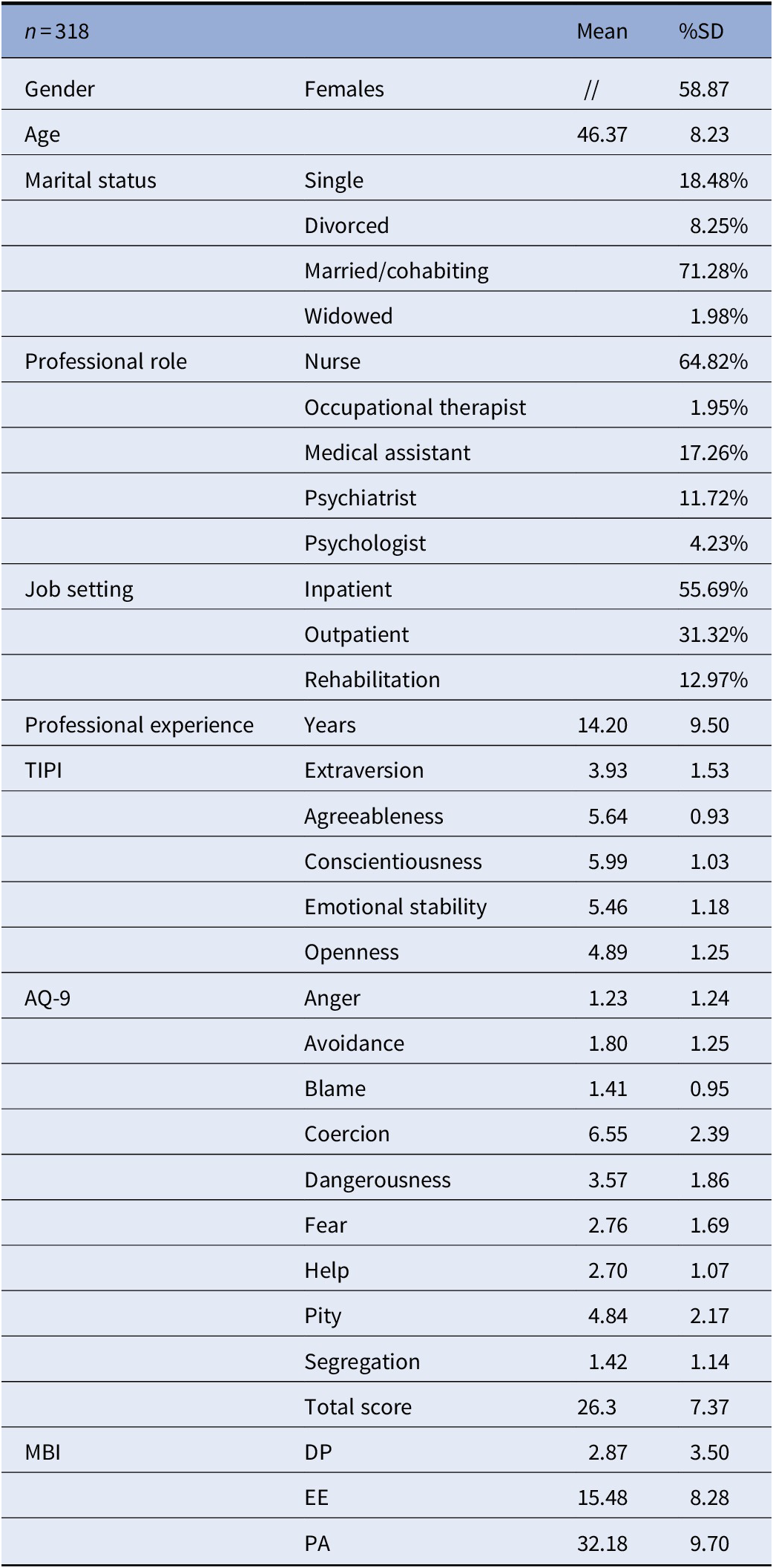

All the community mental health staff were invited to take part in the survey. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. After completion of the questionnaire, anonymity was guaranteed by removing the face sheet including signed informed consent and personal identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth). Those who refused to join the study or did not sign informed consent were excluded. No personal or work experience information could be gathered about excluded subjects. Procedural details have been described and are available elsewhere [Reference Zaninotto, Rossi, Danieli, Frasson, Meneghetti and Zordan39]. The current sample was made of 318 mental health professionals including psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, and medical assistants (Table 1).

Table 1. Description of the sample including demographic features, personality traits, stigma, and burnout measures.

Abbreviations: AQ-9, Attribution Questionnaire-9; DP, depersonalization; EE, emotional exhaustion; MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; PA, personal accomplishment; TIPI, Ten-Item Personality Inventory.

The primary objective of our study was to understand what may influence stigmatizing attitudes among mental health professionals, considering personality, professional experience, and levels of burnout, by means of a combination of network analysis and moderator analyses.

The following demographic and professional information were collected from participants: age, gender, years of education, marital status, professional role, years of work experience in the CMHS, and main place of employment within the CMHS (inpatient unit, outpatient unit, or rehabilitation unit). Then, to assess stigma, we used the Attribution Questionnaire-9 (AQ-9) [Reference Corrigan, Powell and Michaels45], a brief version of the AQ-27 [Reference Corrigan, Markowitz, Watson, Rowan and Kubiak46,Reference Corrigan, Rowan, Green, Lundin, River and Uphoff-Wasowski47], a questionnaire developed by Corrigan on the basis on the Attribution Theory [Reference Weiner48], which has been widely used in stigma research [Reference Brown49–Reference Law, Rostill-Brookes and Goodman52]. To assess personality traits, we used the Italian version of a brief instrument based on the Five Factor model of personality [Reference Costa and McCrae40], the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) [Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann53,Reference Chiorri, Bracco, Piccinno, Modafferi and Battini54]. The experience of burnout was measured using the Italian version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [Reference Maslach and Jackson55,Reference Sirigatti, Stefanile and Menoni56], which consists of 22 items measuring the three different components of burnout (EE, DP, and PA). Again, a detailed description of the instruments is available elsewhere [Reference Zaninotto, Rossi, Danieli, Frasson, Meneghetti and Zordan39].

Network analysis

We examined a network composed of personality traits as measured by the TIPI, stigmatizing beliefs derived from the total score of the AQ-9, and burnout dimensions as measured by the MBI in a sample of mental health professionals. Network analysis has been performed with RStudio [57,Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried58] using qgraph package as detailed elsewhere [Reference Borsboom and Cramer43,Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried58–Reference Solmi, Collantoni, Meneguzzo, Degortes, Tenconi and Favaro63].

When using a network analysis approach to describe the complex interactions among a set of variables [Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried58,Reference Cuthbert64–Reference Wildes and Marcus66], these latter are represented as nodes, connected by edges, which are the visual representation of the correlation among nodes. In this perspective, nodes are reciprocally connected in a self-maintaining complex network of associations. However, network analysis does not allow any causal inference. More specifically, edges (correlations) of a network are undirected, and, unless longitudinal data are used, additional analyses must supplement network analysis to formulate any path or process hypothesis. With this network analysis, a graphical model of the network of included variables was built [Reference Haslbeck and Waldorp59], as well as several properties of the estimated network were measured [Reference Epskamp, Constantini, Cramer, Waldorp, Schmittmann and Borsboom67]. Since an excess of sparse correlations may constitute noise and would confuse rather than inform, we applied a penalty to correlations close to zero, in order to retain only meaningful associations. Such operation is also defined as a “least absolute shrinkage and selection operator” [Reference Friedman, Hastie and Tibshirani68] regularization (a sort of shrinkage of small edges to zero), which was applied in order to only retain more solid edges (regularized partial correlations). Such regularization has been determined by setting Extended Bayesan Information Criterion [Reference Chen and Chen69], a parameter that sets the degree of regularization/penalty applied to sparse correlations to 0.5. We considered centrality indices of nodes that are relevant, since they describe how strongly the nodes are interconnected with several other nodes of the network. Centrality of nodes was estimated with node strength (i.e., the absolute sum of edge weights) [Reference Costantini, Epskamp, Borsboom, Perugini, Mottus and Waldrop60]. As a proxy of reliability of a network’s estimates, we measured the stability of the network, by re-calculating centrality indices after dropping growing percentages of the included participants [Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried58]. To quantify stability of the centrality indices, the correlation stability coefficient was calculated with a threshold of 0.25 indicating reliable stability. Finally, we measured edges’ accuracy by means of “nonparametric” bootstrapping (n boots = 1,000).

Moderator analysis

Given that network analysis, together with the cross-sectional nature of the present study, does not allow any inference on causality or direction of the interconnections among nodes, we supplemented the network analysis with multiple regression and moderator analyses to identify stigma predictors among network’s nodes. We tested multiple regressions to analyze the influence of the level of burnout on stigma. After the visual inspection of the network, and in consideration of centrality indexes and of the correlation matrix, we identified three models (one for each dimension of burnout) to test what specific path could increase stigma in mental health professionals. We set the gender as a covariate. To obtain comparable coefficients, we mean-centered each predictor of the model; for gender, we used an orthogonal contrast coding that allows to compare, for each coefficient, the corresponding level of the factor to the average of the other levels. Whenever a significant interaction emerged, we computed a simple slope analysis: in particular, we refitted the original regression, centering the mediator to a standard deviation above and below its mean [Reference Baron and Kenny70,Reference Holmbeck71]. We fitted three multiple regression models, one per burnout dimension. Given the multiple testing, we decided to correct all the p values with the False Discovery Rate correction [Reference Benjamini and Hochberg72]. We computed all the statistical analysis by means of the R statistical software (http://www.r-project.org) version 2.10.0. Statistical analyses were run by U.G.

Results

Network analysis

Characteristics of included sample are reported in Table 1. Out of 318 questionnaires, we included 265 subjects without missing data in this network analysis.

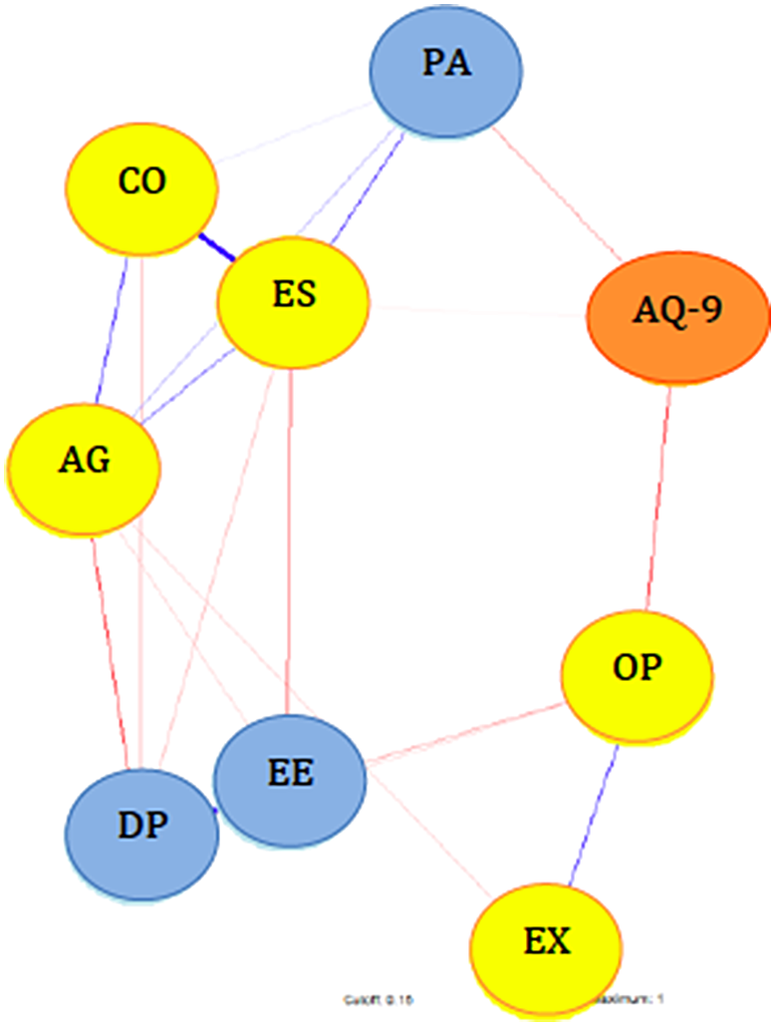

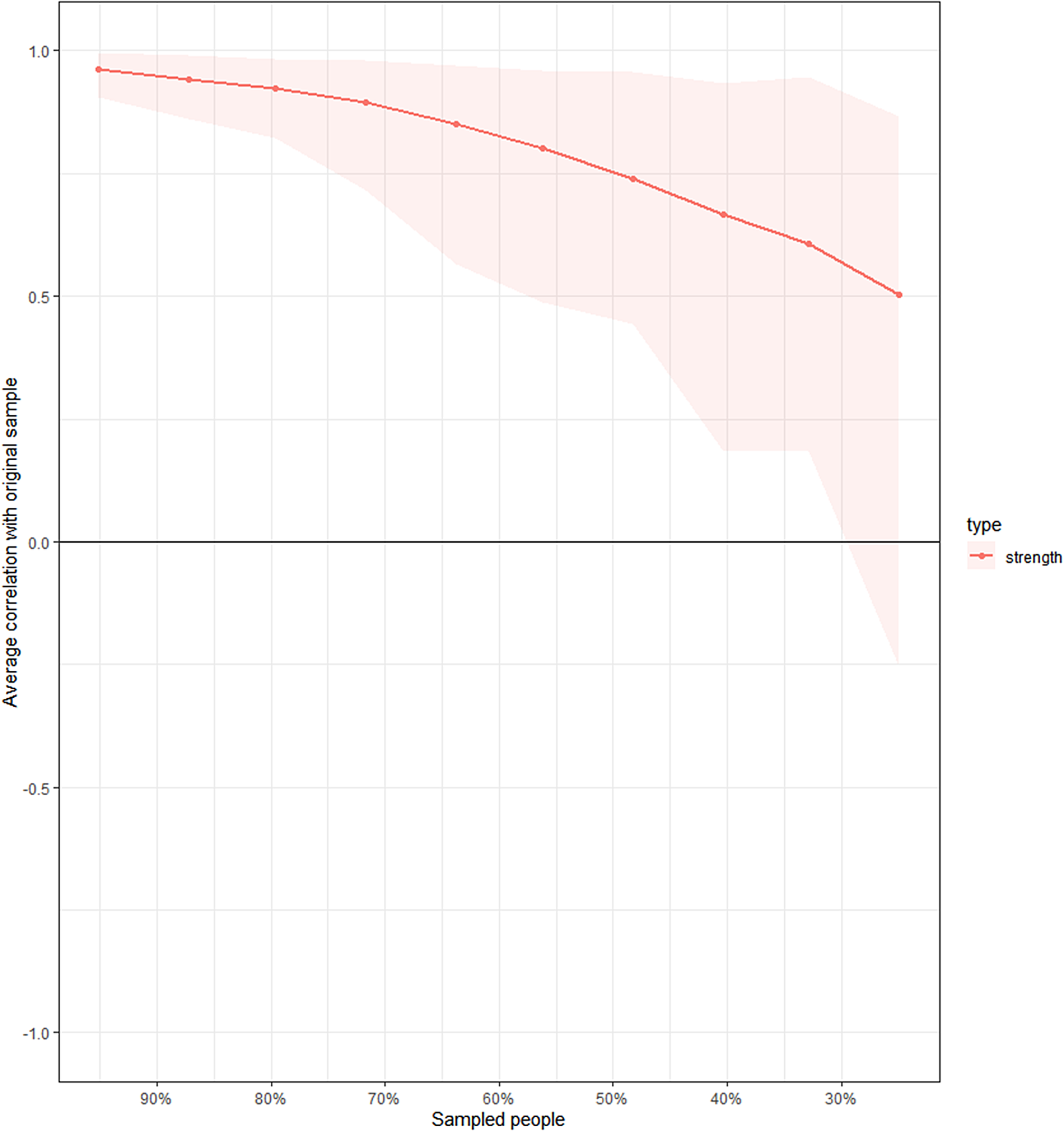

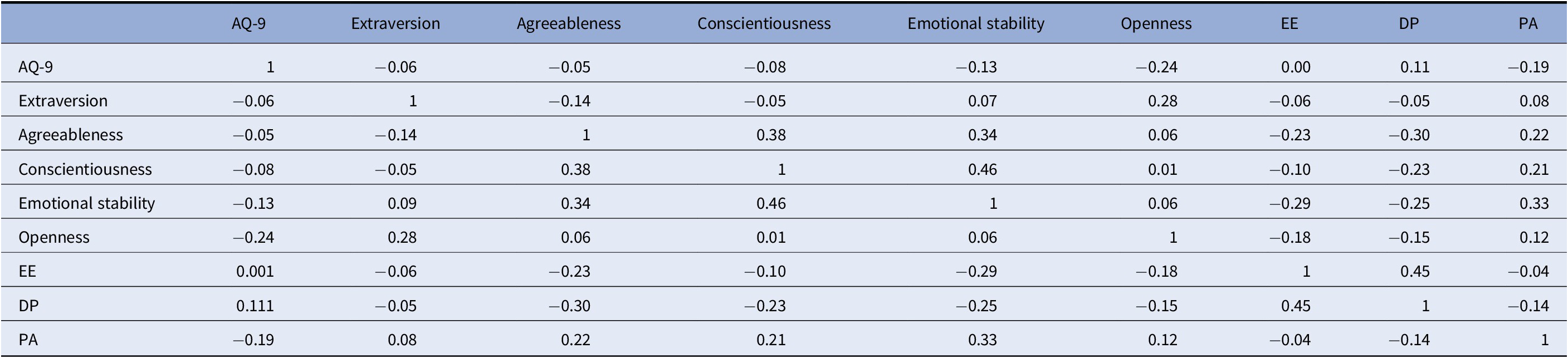

The network is represented in Figure 1. Centrality estimates of the nodes of the network are reported in Table 2. Among personality nodes, emotional stability had the highest centrality. Given the small sample size, the network did not meet required stability indexes (stability coefficient = 0.24 vs. reliability thresholds = 0.25) as shown in Figure 2. At visual inspection of the network, openness was the only one directly connected with stigma. The burnout dimension of PA bridged emotional stability with stigma, while the other burnout dimensions were not directly connected with stigma. In Table 3, the correlation matrix of the network is also available, showing that the highest correlation values with stigma were for openness, emotional stability, and PA.

Figure 1. Network with personality traits, stigma, and burnout dimensions. Abbreviations: AG, agreeableness; AQ-9, Attribution Questionnaire-9; CO, conscientiousness; DP, depersonalization; EE, emotional exhaustion; ES, emotional stability; EX, extraversion; OP, openness; PA, personal accomplishment.

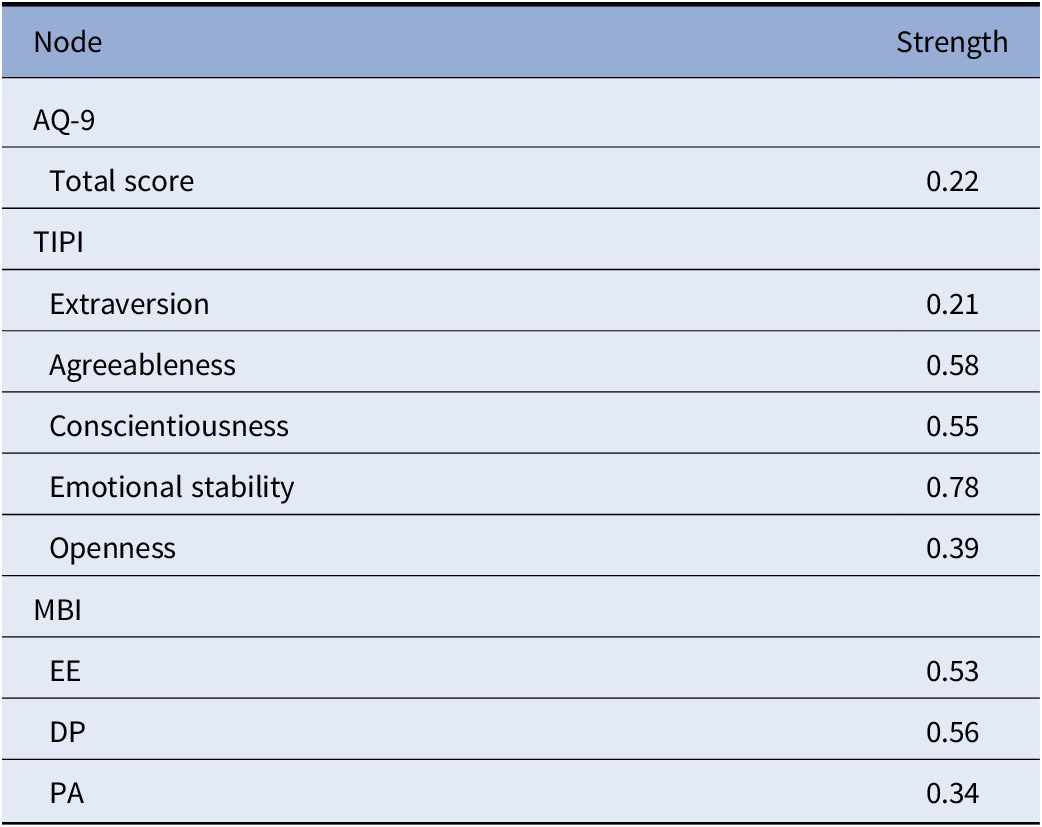

Table 2. Centrality indexes of the network

Abbreviations: AQ-9, Attribution Questionnaire-9; DP, depersonalization; EE, emotional exhaustion; MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; PA, personal accomplishment; TIPI, Ten-Item Personality Inventory.

Figure 2. Stability of the network with progressively dropping proportions of the sample size.

Table 3. Network correlation matrix including personality, burnout, and stigma

Abbreviations: AQ-9, Attribution Questionnaire-9; DP, depersonalization; EE, emotional exhaustion; PA, personal accomplishment.

Multiple regression and moderator analysis

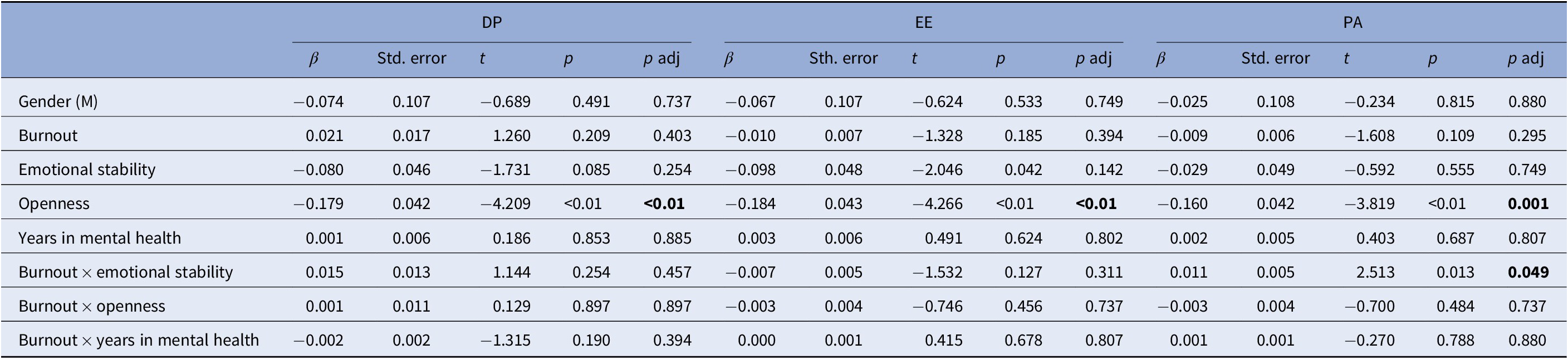

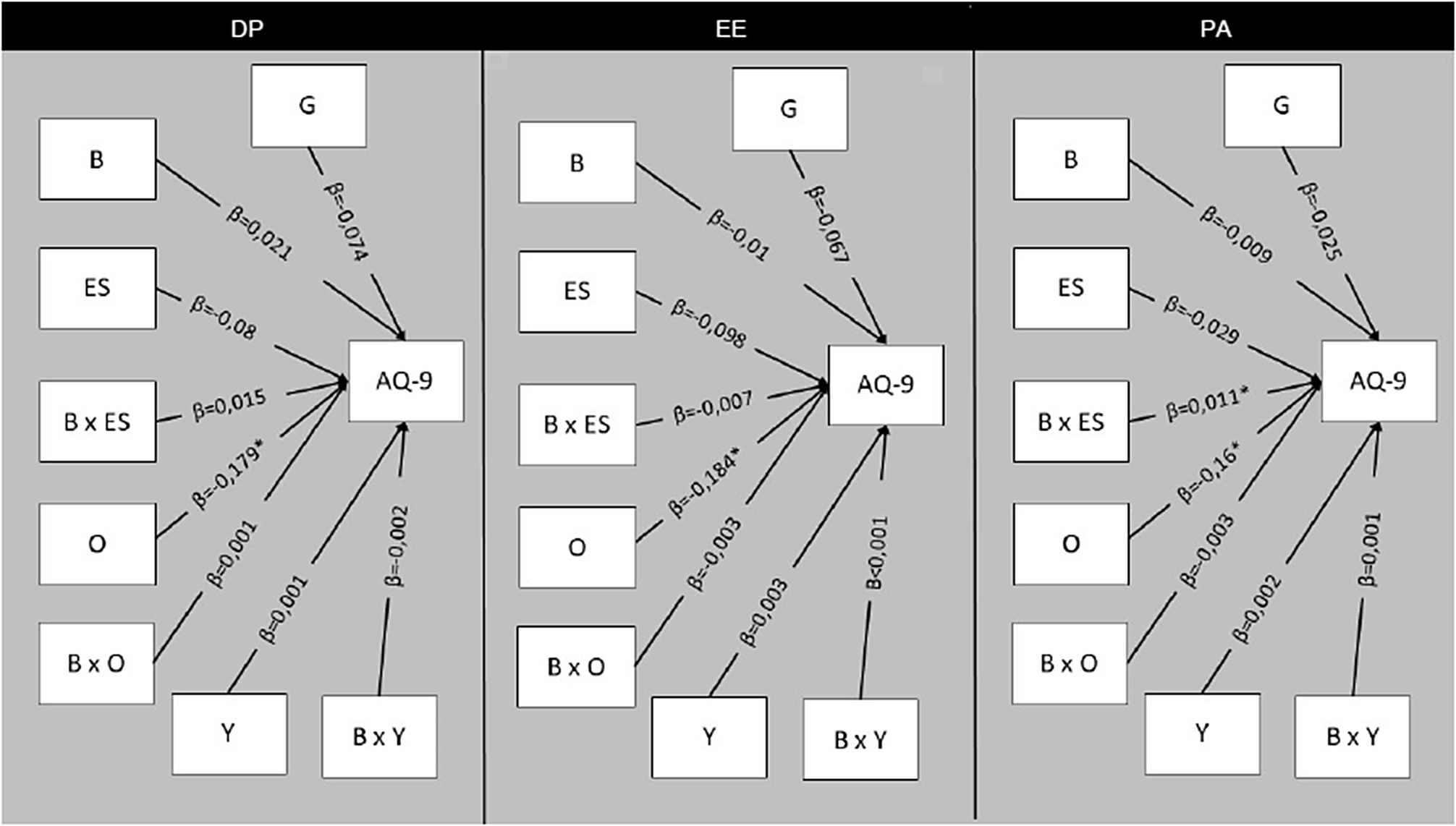

All the regressions’ result are displayed in Table 4 and represented in Figure 3.

Table 4. Results of the multiple regression model including predictors of stigma in mental health professionals

Bold p-values indicate significant predictors.

Abbreviations: DP, depersonalization; EE, emotional exhaustion; M, males; PA, personal accomplishment.

Figure 3. Design of the moderation models including predictors of stigma in a sample of mental health professionals. Abbreviations: *, significant predictors; AQ-9, Attribution Questionnaire-9; B, burnout as indicated by the header of each figure’s section (DP, depersonalization; EE, emotional exhaustion; PA, personal accomplishment); G, gender; ES, emotional stability; O, openness; X, indicates interaction; Y, years in psychiatry.

In the first model including DP, we did not find neither direct nor moderating effect of this dimension of burnout on stigma. However, we found that openness inversely predicted stigma (β = −0.179; p adjusted <0.001) without any moderating effect of other variables.

In the second model, we did not find neither direct nor moderating effect of EE on stigma, but openness was confirmed as an inverse predictor for stigma (β = −0.184; p adjusted <0.001), without any moderating effect of other variables.

Finally, considering PA as a predictor, we confirmed that higher openness scores directly led to a lower negative attitude (β = −0.16; p adjusted = 0.001). Moreover, we found a significant interaction between PA and emotional stability (β = 0.011; p adjusted = 0.049) in affecting stigmatizing attitudes. In particular, we found that the less the worker felt a sense of efficacy (low PA), the more negative was his/her attitude toward patients, an effect which became significant only when the individual reported lower scores on emotional stability (β = −0.023; p adjusted = 0.002).

In all three models, neither gender nor years of experience predicted anyhow (directly or via moderators) stigma.

Discussion

The present study confirmed previous findings by our group [Reference Zaninotto, Rossi, Danieli, Frasson, Meneghetti and Zordan39] on an association between personality and stigma. In our sample, the personality trait of openness resulted to have a relevant effect on the development of stigmatizing attitudes among mental health professionals. Moreover, higher levels of burnout (low PA) were associated to more negative views about clients, in particular in those subjects showing a lower emotional stability.

These findings can have simple but relevant implications for the organization of mental health facilities. First, by pointing at the importance of individual differences on the development of negative attitudes toward patients, they suggest that it may be necessary to consider these differences when addressing the problem of stigma among mental health professionals, especially in the earlier stages of education. Our results are in line with previous studies exploring samples of college students [Reference Brown36] and healthcare students [Reference Yuan, Seow, Abdin, Chua, Ong and Samari37], showing a negative association between stigma and two dimensions of personality, namely agreeableness and openness. Those features may be accompanied by better empathic and communication skills [Reference Sims73], which in turn may affect the type of contact with the patient. In our sample, openness resulted to have a direct effect on stigma. Openness is characteristic of individuals who are more flexible, reflective, sensitive, and imaginative [Reference McAdams41]. People scoring higher on openness may be more prone to develop positive contact experiences, having a better disposition toward understanding the feelings of individuals suffering from mental disorders. Moreover, individuals with higher levels of openness may be more prone to a positive and recovery-oriented attitude, which in turn has been associated to lower levels of stigma [Reference Corrigan, Gause, Michaels, Buchholz and Larson74,Reference Barczyk75].

The second important result is that not all burnout dimensions, but only low PA in conjunction with low emotional stability may have a relevant effect on stigma. Stigma has been consistently associated with burnout among mental health professionals [Reference Calicchia23,Reference Lauber, Nordt, Sartorius, Falcato and Rossler24], to the point that some authors [Reference Holmqvist and Jeanneau76] have also argued that some negative attitudes toward patients may be one of the emotional aspects of burnout. Burnout in mental health professionals has been linked to workload, role conflict, lack of job control, and a reduced sense of autonomy at work [Reference O’Connor, Muller Neff and Pitman77]. In our previous study [Reference Zaninotto, Rossi, Danieli, Frasson, Meneghetti and Zordan39], higher levels of PA were associated to the presence of institutional responses to risk situations (namely, protocols for managing the aggressive or violent behaviors).

A high PA is usually regarded not only as the sense of efficacy and effectiveness of one’s personal resources, but also as the sense of involvement and commitment to one’s job [Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter78], a characteristic which may in turn have an effect on the tendency to engage into positive contacts with patients. Conversely, a high emotional stability is connected to a strong sense of ability to control events, and may act as a protective factor against burnout [Reference Zaninotto, Rossi, Danieli, Frasson, Meneghetti and Zordan39,Reference Papadatou, Anagnostopoulos and Monos79], by facilitating the employment of better coping strategies such as problem-solving and cognitive restructuring [Reference Carver and Connor-Smith80]. Thus, a stronger sense of control, deriving from both personality traits and from workplace’s characteristics, may act as a protective factor against negative attitudes toward patients.

The present work has several limitations. First, the small sample size did not allow to run more fine-grained network analysis and resulted in an unstable network, whose results should be interpreted from a descriptive and qualitative perspective. Second, the present study is cross-sectional and based on self-reported and anonymous measures, which may be affected by some response bias toward social desirability. However, the use of two different statistical techniques may to a certain degree compensate the cross-sectional design of the study and may reveal a direction of effect from personality to burnout to stigma.

In conclusion, mental health professionals having low openness may be more prone to develop stigma, and burnout increases stigma in particular in subjects with lower emotional stability. Mental health service organizations should consider implementation of personality and burnout assessments to promptly intervene and minimize stigma among mental health professionals. Further, as suggested by Yuan et al. [Reference Yuan, Seow, Abdin, Chua, Ong and Samari37], since personality traits continue to develop, especially during young adulthood, future studies should address the role of personality when testing antistigma interventions, especially when they are directed to early stages of education of future healthcare professionals. Finally, given the importance of recovery orientation for stigma research [Reference Angermeyer, Matschinger and Corrigan81–Reference Tsang, Angell, Corrigan, Lee, Shi and Lam83], future studies should address the issue of the relationship among personality traits, stigmatizing beliefs, and recovery orientation among mental health professionals.

Financial Support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.