1. Introduction

The At Risk Mental State (ARMS) construct was introduced two decades ago, in 1996 [Reference Yung, McGorry, McFarlane, Jackson, Patton and Rakkar1], to allow identification of subjects at clinical high-risk for psychosis before full symptoms manifest. Subjects with suspected psychosis risk are usually referred to specialized services, where they undergo a specific psychometric assessment, such as the Comprehensive Assessment of At Risk Mental State (CAARMS) [Reference Yung, McGorry, McFarlane, Jackson, Patton and Rakkar1]. Upon completion of this assessment by expert and trained clinicians, referred subjects are assigned a status of being at risk (ARMS+) or not at risk (ARMS−) for psychosis [Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Schultze-Lutter, Bonoldi and Borgwardt2]. Focused interventions are offered to those deemed ARMS+, in the light of their enhanced risk of developing psychosis [Reference Kempton, Bonoldi, Valmaggia, McGuire and Fusar-Poli3]. Conversely, ARMS− subjects are usually discharged from these services and referred to other teams or to general practitioners [Reference Millan, Andrieux, Bartzokis, Cadenhead, Dazzan and Fusar-Poli4]. Since its inception, the ARMS construct has gained substantial traction to the point that specialist ARMS provision has been recognized as an important component of clinical services for early psychosis intervention [5,6] (e.g. NICE guidelines [Reference Nice7]; recent NHS England Access and Waiting Time [AWT] standard [5], DSM-5 diagnostic manual) [Reference Fusar-Poli, Carpenter, Woods and McGlashan8].

The broad prognostic validity of the ARMS designation is indexed by its ability to improve the pretest risk (for details see [Reference Fusar-Poli and Schultze-Lutter9]) of developing mental disorders in subjects referred to high-risk services (i.e. in those later deemed ARMS+ or ARMS−) [Reference Fusar-Poli, Schultze-Lutter, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Bonoldi and Stahl10]. Conducting long-term studies on ARMS+ and ARMS− cohorts can be complicated due to subject attrition, particularly when following ARMS− individuals. In fact, beyond the original validation study [Reference Yung, Nelson, Stanford, Simmons, Cosgrave and Killackey11], no further large-scale studies have been designed to directly address the long-term clinical validity of the ARMS designation for psychosis prediction [Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Schultze-Lutter, Bonoldi and Borgwardt2]. Our recent meta-analysis showed that the three ARMS studies that are available have reported only indirect data, including small samples [12,13] or an incomplete follow-up of the ARMS− group [Reference Lee, Rekhi, Mitter, Bong, Kraus and Lam14]. Furthermore, the broad long-term clinical outcomes of the ARMS− group remain unknown. As a result, the specificity of the ARMS for the prediction other non-psychotic mental disorders, is not yet fully established. Recent clinical staging models [Reference Nieman and McGorry15] have suggested that ARMS+ subjects may be also at increased risk also for the development of non-psychotic mental disorders. These concerns arise in part because most ARMS+ subjects will not develop full psychosis [Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Borgwardt, Woods, Addington and Nelson16]. Whether the ARMS signposts specifically to risk for future psychosis, or to nonspecific deterioration in mental health, is of paramount relevance for both clinical and research perspectives.

The present study aims to address these gaps in the literature. We used a large, real-world sample of subjects accessing a high-risk service, with a long follow-up period, to investigate the long-term clinical validity of the ARMS assessment. We first reported the pretest risk for the development of any mental disorder, to account for the initial level of risk in this selected population. We then investigated the long-term prognostic accuracy of the ARMS designation for the prediction of both psychotic and non-psychotic disorders.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

We included all non-psychotic subjects assessed for suspicion of psychosis risk by the Outreach and Support in South London (OASIS) high-risk service, South London and the Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) [Reference Fusar-Poli, Byrne, Badger, Valmaggia and McGuire17]. The OASIS is a specialised clinical service for the assessment and treatment of ARMS individuals. Established in 2001 and currently led by one of the authors of the present study (PFP) it is one of the largest services of this type in Europe. All help-seeking subjects referred to OASIS on suspicion of psychosis risk in the period 1st January 2002 to 31st December 2015 were initially considered eligible. We then excluded those who were referred but never assessed by the team, and those who were already psychotic at baseline. The remaining sample was therefore composed of all non-psychotic subjects undergoing a CAARMS-based assessment at OASIS, as part of the standard care. The details of the CAARMS assessment at OASIS are detailed in a separate paper [Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Lee, Beverly and Bonoldi18]. Upon completion of the assessment, these subjects were assigned the status ARMS+ or ARMS−. Details of the specific care received at OASIS team have been described elsewhere [Reference Fusar-Poli, Frascarelli, Valmaggia, Byrne, Stahl and Rocchetti19].

2.2. Study measures

The primary outcome of interest was the hazard ratio (HR) of developing any ICD-10 non-organic mental disorders in ARMS+ subjects as compared to ARMS− subjects (see supplementary data, eMethod 1).

Time to diagnosis of a mental disorder was measured from the date of the ARMS assessment conducted at the OASIS, censored at 1st March 2016.

Descriptive sociodemographic variables were: age [Reference Kirkbride, Errazuriz, Croudace, Morgan, Jackson and Boydell20], gender [Reference Kirkbride, Errazuriz, Croudace, Morgan, Jackson and Boydell20], ethnicity [Reference Kirkbride, Errazuriz, Croudace, Morgan, Jackson and Boydell20] (black, white, Asian, Caribbean, mixed, other), familial environment [Reference Gonzalez-Pinto, Ruiz de Azua, Ibanez, Otero-Cuesta, Castro-Fornieles and Graell-Berna21] (marital status: married, divorced or separated, single, in a relationship), and socioeconomic status [Reference Lasalvia, Bonetto, Tosato, Zanatta, Cristofalo and Salazzari22] (index of multiple deprivation, IMD 2015 [23], see supplementary data, eMethod 2). All sociodemographic variables were those recorded closest to the time of first referral to OASIS.

2.3. Procedure

Clinical register-based cohort study. Primary outcome and sociodemographic variables were automatically extracted from electronic medical records with the use of the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) tool [Reference Stewart, Soremekun, Perera, Broadbent, Callard and Denis24] (see supplementary data, eMethod 3).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic characteristics of the ARMS+ vs. ARMS− samples were described by means and SDs for continuous variables, and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Baseline ARMS+ vs. ARMS−characteristics were compared using Student's t-tests and Chi2. The clinical validity of the ARMS assessment was investigated with Cox proportional hazards models (non-competing risk), evaluating the effects of ARMS status (ARMS+ vs. ARMS−) on the development of any incident mental disorders (any mental disorders, psychotic disorders, non-psychotic disorders) and time to development of these disorders, after checking for proportional hazards assumption [Reference Grambsch and Therneau25]. Incident disorders were defined as the emergence of an ICD-10 primary diagnosis from the aforementioned groups, at any time during the follow-up, when no primary diagnosis in that ICD-10 group was present at baseline (in the first three months following referral to OASIS). We also described the impact of ARMS+ subgroups (Attenuated Psychotic Symptoms [APS]; Genetic Risk and Deterioration [GRD]; Brief and Limited Intermittent Psychotic Symptoms [BLIPS]) vs. ARMS− on the development of incident mental disorders, psychotic disorders and non-psychotic disorders. Subjects meeting multiple ARMS criteria were stratified for symptom severity as previously suggested [Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Borgwardt, Woods, Addington and Nelson16]: any BLIPS > APS or APS + GRD > GRD alone. We further described the cumulative incidence of the outcome of interest with Kaplan–Meier failure function (1-survival) [Reference Kaplan and Meier26]. Clinical validity (apparent performance) was determined with the C statistic (area under the curve [AUC]). All analyses were conducted in STATA 13 (STATA Corp., TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

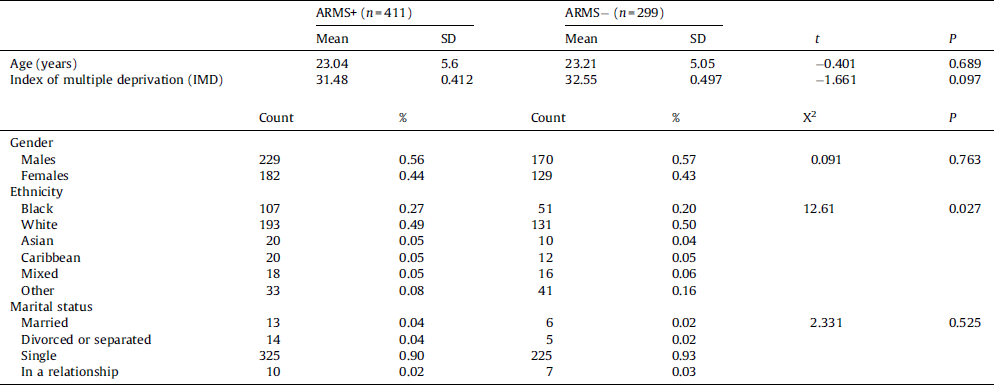

From 2002 to 2015, a total of 1115 subjects were referred to the OASIS clinic for ARMS assessment. Among them, 125 subjects did not undergo the ARMS assessment and had no contact with the OASIS service. An additional 280 subjects were already psychotic at baseline (the clinical fate of these subjects is described elsewhere [Reference Fusar-Poli, Diaz-Caneja, Patel, Valmaggia, Byrne and Garety27]). A final sample of 710 non-psychotic subjects who underwent ARMS assessment was used in the analyses. The sample included 411 ARMS+ subjects and 299 ARMS− subjects (Table 1). The average age of the sample was 23 years (range 12–44), with 56% males. Half of the sample was of white ethnicity, the vast majority was single and the mean IMD score was 32%. There were no significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics between ARMS+ and ARMS−, with the exception of ethnicity; there were more ARMS+ subjects of black ethnicity as compared to ARMS− subjects. The mean follow-up time was of 1472 days (SD 1171 days).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of subjects undergoing ARMS assessment at the OASIS clinic (n = 710).

ARMS: At Risk Mental State; OASIS: Outreach And Support in South London.

3.2. Pretest risk of developing any mental disorders in subjects undergoing ARMS assessment

The pretest probability of developing any mental disorder in the entire pool of subjects undergoing ARMS assessment (n = 710, Fig. 1), indicated a 6-year cumulative incidence of 0.44 (95% CI: 0.395–0.494). Since the last failure was observed at 2192 days/6.01 years, when 133 subjects were still at risk (not censored), in the following analyses we report the descriptive cumulative incidence of the failure functions at this timepoint.

Fig. 1 Cumulative incidence (Kaplan–Meier failure function) for pretest risk of developing any mental disorders in subjects undergoing At Risk Mental State (ARMS) assessment. The dotted line indicates the last event (failure) at 2192 days.

3.3. Long-term clinical validity of the At Risk Mental State

3.3.1. Prediction of any mental disorder

There were no significant between-group differences in hazard risks (HR = 0.979, Table 2). The 6-year cumulative incidence was 0.445 (95% CI: 0.387–0.507) in the ARMS+, and 0.431 (95% CI: 0.347–0.525) in the ARMS− (supplementary data, eFigure 1). The mean time to event in ARMS+ was 2979 days (95% CI: 2733–3225) and in ARMS− was 2584 (95% CI: 2299–3225).

Table 2 Long-term clinical validity of the ARMS for the prediction of mental disorders. Cox proportional hazards analyses. Failure events were defined as the emergence of an ICD-10 primary diagnosis from the different groups, at any time during the follow-up, when no primary diagnosis in that ICD-10 group was present at baseline.

ARMS: At Risk Mental State; na: not available; Se: sensitivity; Sp: specificity; AUC: area under the curve.

a ARMS+ vs. ARMS− (base).

3.3.2. Prediction of psychotic disorders

There were significant between-group differences in hazard risk, with higher risk of psychosis in the ARMS+ as compared to the ARMS− (HR = 4.83, Table 2). The 6-year cumulative incidence was 0.201 (95% CI: 0.161–0.250) in the ARMS+ and 0.042 (95% CI: 0.022–0.076) in the ARMS− (Fig. 2). The mean time to event in ARMS+ was 4124 days (95% CI: 3933–4315) and in ARMS− was 3940 days (95% CI: 3847–4033).

Fig. 2 Cumulative incidence (Kaplan–Meier failure function) for the long-term risk of development of psychotic disorders in At Risk Mental State (ARMS)+ (n = 411) and ARMS− (n = 299) subjects. LR+ 1.612, LR− 0.276.

At the 6-year timepoint, the ARMS assessment showed a very good sensitivity (0.873, Table 2) but only a modest specificity (0.456). This was reflected by a moderate negative likelihood ratio (LR−) of 0.276 and a small positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 1.612 (for details on LR−, LR+ and probabilistic prognostic reasoning in ARMS see [Reference Fusar-Poli and Schultze-Lutter9]), with a modest AUC (mean 0.68, 95% CI: 0.62–0.70).

3.3.3. Prediction of non-psychotic disorders

There were significant between-group differences in hazard risks between the ARMS+ and ARMS− (HR = 0.545, Table 2), with higher risk of non-psychotic disorders in the ARMS− than in the ARMS+ group. The 6-year cumulative incidence was 0.281 (95% CI: 0.226–0.347) in the ARMS+ and 0.404 (95% CI: 0.320–0.501) in the ARMS− (supplementary data, eFigure 2). The mean time to event in ARMS+ was 3710 days (95% CI: 3473–3946), and in ARMS− 2691 days (95% CI: 2404–2978).

3.3.4. Prediction of specific non-psychotic disorders

There were no significant between-group differences in the hazard risks for the development of bipolar mood disorders (supplementary data, eFigure 3), non-bipolar mood disorders (supplementary data, eFigure 4), anxiety disorders (supplementary data, eFigure 5), substance use disorders, disorders with childhood/adolescence onset, or physiological syndromes (Table 2 and supplementary data, eResults). Conversely, there was higher risk of development of personality disorders (48% of the failures were coded as ICD-10 F63 emotionally unstable personality disorders) in the ARMS− as compared to the ARMS+ group (HR = 0.179, Table 2). The 6-year cumulative incidence was 0.022 (95% CI: 0.009–0.054) in the ARMS+ and 0.095 (95% CI: 0.058–0.154) in the ARMS− (supplementary data, eFigure 6). There was also higher risk of developing developmental disorders in the ARMS− as compared to the ARMS+ (HR = 0.339, Table 2) but there were only a very few (n = 2) failures. The 6-year cumulative incidence was 0.019 (95% CI: 0.004–0.090) in the ARMS−, while there were no failures in the ARMS+ subgroup.

3.3.5. ARMS subgroups and prediction of mental disorders

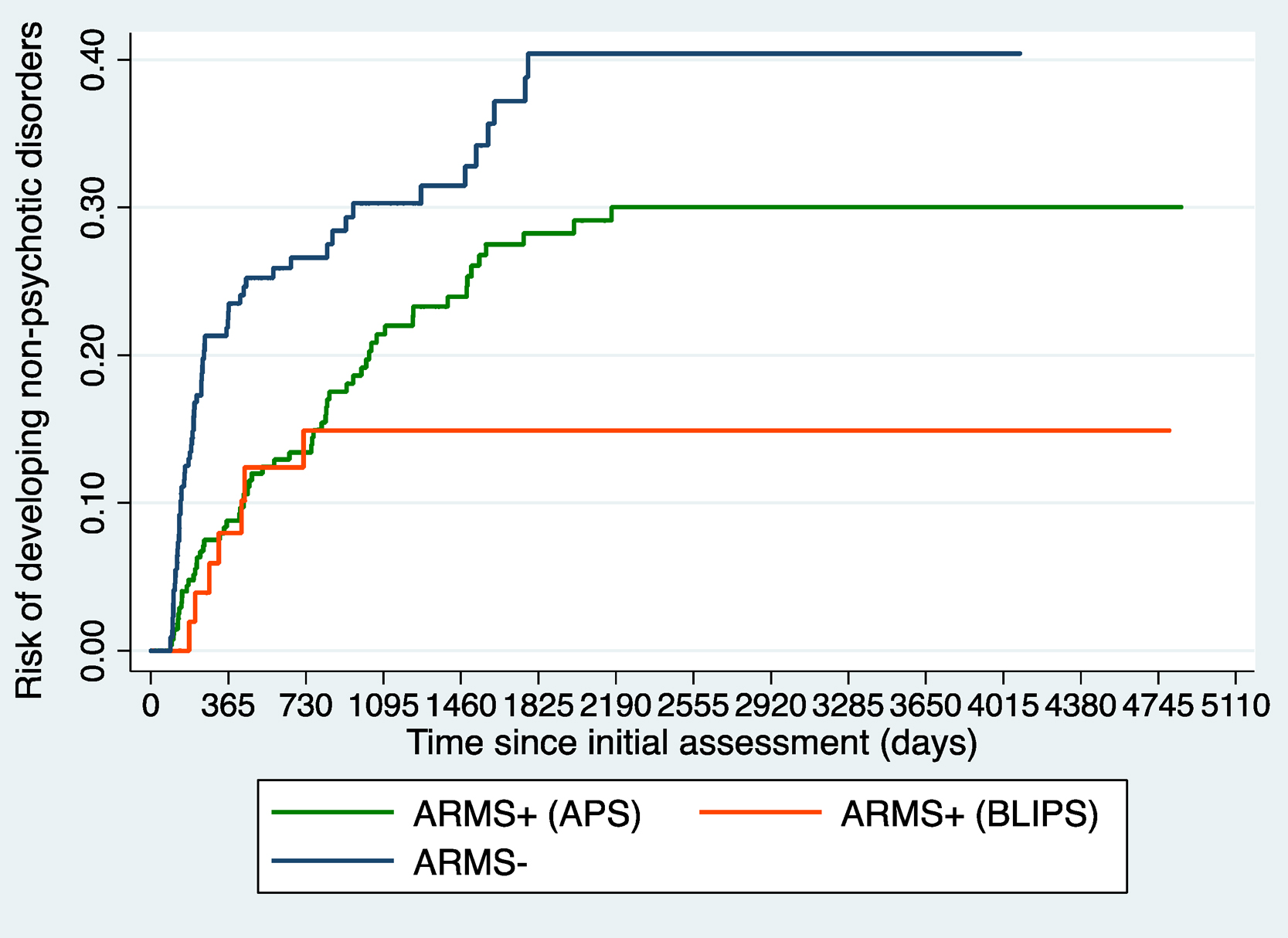

There were not enough cases in the GRD subgroup to allow meaningful statistical analyses (n = 6). These subjects were therefore discarded from the following analyses. When the APS and BLIPS subgroups where compared with ARMS−, there were no significant between-group differences in the risk of development of any mental disorders (P = 0.892). However, there were significant differences in the risk of developing psychotic disorders between the groups (P < 0.001). There were also significant between-group differences in the risk of developing non-psychotic mental disorders (P < 0.001), with the lowest risk in the BLIPS subgroup, the highest risk in the ARMS− subgroup and the APS subgroup in an intermediate position (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Cumulative incidence (Kaplan–Meier failure function) for the long-term risk of development of non-psychotic disorders in At Risk Mental State (ARMS)+ (APS) (n = 299), ARMS+ (BLIPS) (n = 62) and ARMS− (n = 228) subjects.

4. Discussion

This study has the largest sample size and longest follow-up period of any study that has investigated the real-world clinical validity of the ARMS designation. In subjects undergoing ARMS assessment, the 6-year pretest risk for the development of any mental disorder was 0.44 and higher than in unselected samples. At 6-year follow-up, the ARMS+ group was associated with a fivefold risk of developing psychosis as compared to the ARMS− group. In the long-term, the CAARMS retained very good sensitivity but only modest specificity. The ARMS+ was associated with a lower risk of developing non-psychotic disorders (mostly personality disorders) relative to the ARMS−. Among ARMS+ subgroups, the BLIPS subgroup had a lower risk of developing non-psychotic disorders than the APS subgroup.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the risk of developing any mental disorder (psychotic and non-psychotic) in subjects undergoing and completing an ARMS assessment. Understanding whether the ARMS status delineates specific risk for developing mental disorders necessarily relies upon the reporting of incident rates of different classes of psychiatric disorders. Because our database drew directly from real-world and real-time electronic health records, we were able to track the incident diagnoses of all ICD-10 non-organic mental disorders. This approach allowed us to estimate the overall burden of risk of subjects referred to high-risk services. We found that their overall pretest risk of developing any mental disorder (i.e. before completion of the ARMS assessment) accumulated to approximately 44% at 6 years. This value is higher than the 6-year incidence of 27.84% (95% CI: 27.24%–28.44% estimated from a previous study [Reference Hardoon, Hayes, Blackburn, Petersen, Walters and Nazareth28]) for any mental disorder in primary care settings, consistent with ARMS subjects representing selected help-seeking samples. These findings are in line with the recently observed risk enrichment and increased vulnerability for the development of mental disorders in subjects seeking help from high-risk services [Reference Fusar-Poli, Schultze-Lutter, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Bonoldi and Stahl10]. Because the observe pretest risk enrichment is substantial, pretest risk stratification models have been recently developed and validated by our group [Reference Fusar-Poli, Rutigliano, Stahl, Schmidt, Ramella-Cravaro and Shetty29].

The CAARMS assessment then defined the ARMS+ and ARMS− groups from this selected and help-seeking population. There was no significant difference in the overall 6-year cumulative incidence of any mental disorders between ARMS+ (45%) and ARMS− (43%) (supplementary data, eFigure 1). However, there was an increased risk for psychotic disorders in ARMS+ and an increased risk for non-psychotic disorders in the ARMS−.

We have thus replicated the earlier findings of the original validation study [Reference Yung, Nelson, Stanford, Simmons, Cosgrave and Killackey11] by confirming that the ARMS+ was associated with greater risk of developing psychotic disorders, even in the longer term. The ARMS assessment retained a good ability to rule out psychosis (as reflected by the high sensitivity, 0.873), but was associated with an inadequate ability to rule in psychosis (as reflected by the modest specificity, 0.456) (Fig. 2). Similarly, the LR− of 0.276 indexed a moderate [Reference McGee30] decrease of pretest probability for psychosis following an ARMS− designation, while the LR+ of 1.612 indexed only a slight [Reference McGee30] increase in pretest probability for psychosis following an ARMS+ designation. These results indicate a modest long-term prognostic accuracy (AUC 0.68) and the need to specifically improve the ability to rule in subsequent psychosis, while preserving the outstanding ability to rule it out. As the clinical gain of testing positive at an ARMS assessment is modest, it is therefore essential to use it in samples that are already risk enriched such as those accessing mental health services [Reference Fusar-Poli, Schultze-Lutter and Addington31]. The use of the ARMS assessments outside clinical samples is likely to dilute the pretest risk and consequently the transition rates to psychosis [Reference Fusar-Poli32]. Sequential testing with combinations of predictive models deriving from clinical, neurocognitive and biological domains are currently being investigated to overcome some of these caveats [Reference Schmidt, Cappucciati, Radua, Rutigliano, Rocchetti and Dell’Osso33].

Conversely, the ARMS+ was not associated with a higher risk of developing mental disorders other than psychosis, relative to the ARMS− (supplementary data, eFigure 2). Although the risk for non-psychotic disorders was significantly lower in the ARMS+ relative to the ARMS−, approximately 27% of ARMS+ developed a non-psychotic disorder by the 6-year timepoint. This comes in addition to the high baseline prevalence of non-psychotic comorbid disorders [Reference Fusar-Poli, Bechdolf, Taylor, Bonoldi, Carpenter and Yung34], impaired functioning [Reference Fusar-Poli, Rocchetti, Sardella, Avila, Brandizzi and Caverzasi35] and the persistence of non-psychotic comorbid disorders over follow-up [Reference Lin, Wood, Nelson, Beavan, McGorry and Yung36] in ARMS+ samples. Taken together, these results do not support the notion of diagnostic pluripotentiality in the ARMS+. As a risk state specific for psychosis, the possible outcomes specifically associated with the ARMS+ designation may include onset of psychotic disorders, remission or persistence of initial ARMS symptoms and variable functional outcomes, but not an increased risk of emergence of non-psychotic mental disorders.

We also specifically investigated the type of non-psychotic disorders associated with an ARMS designation. We confirmed the findings of previous studies in clinical high-risk samples, reporting no increased risk for bipolar mood disorders, non-bipolar mood disorders or anxiety disorders [Reference Webb, Addington, Perkins, Bearden, Cadenhead and Cannon37]. Our 6-year 1.7% cumulative incidence for bipolar disorders in the ARMS+ (supplementary data, eFigure 3) matches (albeit at different timepoints) to the previous 1.9% reported in the NAPLS-1 cohort [Reference Webb, Addington, Perkins, Bearden, Cadenhead and Cannon37]. Similarly, our 6-year 11.4% cumulative incidence for anxiety disorders (supplementary data, eFigure 5) in the ARMS+ is close to the 10.8% rate reported in the PREDICT sample [Reference Webb, Addington, Perkins, Bearden, Cadenhead and Cannon37]. Conversely, our 6-year 10% cumulative incidence of non-bipolar mood disorders (supplementary data, eFigure 4) appeared higher than the rates reported in NAPLS-1 [Reference Webb, Addington, Perkins, Bearden, Cadenhead and Cannon37]. However, the comparability of these findings may be problematic due to the different time-points, study designs employed and the operational differences between the CAARMS and the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes (SIPS) [Reference McGlashan, Walsh and Wood38]. More importantly, the cumulative incidences of these non-psychotic disorders in the ARMS+ are similar to the annualized 6-year rates estimated from studies conducted in general community studies for bipolar disorders (0.08% estimated from [Reference Hardoon, Hayes, Blackburn, Petersen, Walters and Nazareth28]), non-bipolar mood disorders (8.29% estimated from [Reference Rait, Walters, Griffin, Buszewicz, Petersen and Nazareth39]) and anxiety disorders (9.48% estimated from [Reference Grant, Goldstein, Chou, Huang, Stinson and Dawson40]). Moreover, the cumulative incidence of these disorders in the ARMS+ was lower than in population-based studies of young adults at high-risk of bipolar [Reference Hafeman, Merranko, Axelson, Goldstein, Goldstein and Monk41], non-bipolar mood [Reference Klein, Shankman, Lewinsohn and Seeley42] and anxiety [Reference Wittchen, Jacobi, Rehm, Gustavsson, Svensson and Jonsson43] disorders. Overall, these findings suggest that the ARMS could not effectively be used as a preventative paradigm to alter the course of these non-psychotic disorders.

We have also shown, for the first time, no differences between ARMS+ and ARMS− in risk for the development of substance use disorders, disorders with childhood/adolescence onset or physiological syndromes, and uncertain findings with respect to developmental disorders (due to the rare events). Conversely, we found that the ARMS− group had an increased risk for the development of personality disorders (supplementary data, eFigure 6). The 6-year cumulative incidence of personality disorders was high in the ARMS−, at 9.5%. Unfortunately, it is not possible to compare this incidence rate with that of the general population because the latter is unknown. Studies in patients admitted to psychiatric services have reported incidence rates of ICD-10 personality disorders of 11% during a 12-year period [Reference Pedersen and Simonsen44] (supplementary data, eDiscussion 1). Future studies may compare risk of development of non-psychotic disorders between subjects undergoing ARMS assessment and healthy controls.

We additionally explored the impact of the type of ARMS subgroup on long-term clinical outcomes. We have previously shown that relative to the APS subgroup, the BLIPS subgroup has a greater risk of developing psychosis [Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Borgwardt, Woods, Addington and Nelson16]. In previous publications, we also demonstrated that risk of developing psychosis in BLIPS cases is comparable to concurrent ICD-10 diagnoses traditionally employed to describe brief psychotic episodes [Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Bonoldi, Hui, Rutigliano and Stahl45]. The current findings provide further evidence for the distinctiveness of the BLIPS subgroup as compared to the APS [45,46]. More specifically, we found that the BLIPS were less likely to transition to non-psychotic disorders, relative to the APS. The high specificity towards psychosis, coupled with the low risk of development of non-psychotic disorders, suggest that the BLIPS subgroup is composed of psychotic subjects with an endophenotype of the disorder that is characterized by short and remitting phases and may represent a distinct clinical stage as compared to the APS subgroup [Reference Fusar-Poli47].

The principal limitation of the current study is that we did not employ a structured psychometric interview to ascertain the type of incident diagnoses at follow-up. Therefore, while the incident diagnoses are high in ecological validity (i.e. they represent real-world clinical practice), they have not been subjected to formal validation with research-based criteria. However, as previously noted in these samples [Reference Webb, Addington, Perkins, Bearden, Cadenhead and Cannon37], the use of structured diagnostic interviews can lead to selection of patient subsamples and introduce additional biases. Furthermore, there is also meta-analytical evidence indicating that for some psychotic categories, administrative data recorded in clinical registers are generally predictive of true diagnosis [Reference Davis, Sudlow and Hotopf48].

5. Conclusions

Subjects meeting ARMS criteria have a specific higher risk of developing psychotic disorders, whilst they are not at increased risk of developing other non-psychotic disorders. Among ARMS subjects, those meeting the BLIPS criteria have a distinct clinical outcome.

Financial support

This study was supported in part by a 2014 NARSAD Young Investigator Award to Paolo Fusar-Poli.

Ethical approval

Oxfordshire REC C (Ref: 08/H0606/71+5) for collection and analysis of data from the BRC Case Register (CRIS).

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Appendix A Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.11.010.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.