1. Introduction

Mental disorders are treatable and potentially preventable [Reference Barrera, Torres and Muñoz1–Reference Waddell, Hua, Garland, Peters and McEwan3]. Yet, they continue to be prevalent and to cause significant personal and societal costs and burdens [Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari and Erskine4–Reference Wittchen, Jacobi, Rehm, Gustavsson, Svensson and Jönsson6], because help-seeking is often delayed or absent [Reference Wang, Angermeyer, Borges, Bruffaerts, Tat Chiu and De Girolamo7, Reference Penttilä, Jääskeläinen, Hirvonen, Isohanni and Miettunen8]. Therefore, many approaches to improve mental health focus on understanding and improving help-seeking for mental problems on population level [Reference Campion, Bhui and Bhugra9, Reference Kalra, Christodoulou, Jenkins, Tsipas, Christodoulou and Lecic-Tosevski10]. Of the multiple barriers towards help-seeking for mental disorders [Reference Andrade, Alonso, Mneimneh, Wells, Al-Hamzawi and Borges11–Reference Schnyder, Panczak, Groth and Schultze-Lutter19], negative, stigmatising attitudes as well as knowledge about mental (ill-)health and its treatment, i.e., mental health literacy (MHL), are important interconnected factors [Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko and Bezborodovs13, Reference Schnyder, Panczak, Groth and Schultze-Lutter19] that, however, have not been studied together for their impact on healthcare utilisation.

The term “stigma” comprises public and personal attitudes and behavioural responses towards people with mental problems and towards help-seeking for mental disorders that are formed by cognition and affect [Reference Dividio, Hewstone, Glick, Esses, Dividio, Hewstone, Glick and Esses20, Reference Fiske, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzey21]. A recent meta-analysis identified two aspects of mental disorder-related stigma associated specifically with actual help-seeking, i.e., healthcare utilisation, in the general population: personal attitudes towards individuals with mental disorders (PersonS) and attitudes towards mental health help-seeking (HelpA) [Reference Schnyder, Panczak, Groth and Schultze-Lutter19]. Both these attitudes consist of a cognitive-behavioural and cognitive-affective component differentially related to help-seeking. The cognitive-behavioural aspect of PersonS is often measured as a wish for social distance from persons with a mental disorder (WSD) [Reference Link, Phelan, Bresnahan, Stueve and Pescosolido22], whereas the cognitive-affective aspect of PersonS is often measured as perceived dangerousness of persons with mental disorder [Reference Link, Phelan, Bresnahan, Stueve and Pescosolido22, Reference Jorm, Reavley and Ross23]. WSD consistently showed negative associations with help-seeking [Reference Interian, Ang, Gara, Link, Rodriguez and Vega24, Reference Aromaa, Tolvanen, Tuulari and Wahlbeck25], while cognitive-affective aspects including perceived dangerousness did not show direct associations with help-seeking [Reference Cooper, Corrigan and Watson26, Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer27] but mediated the former relationship [Reference Lee, Laurent, Wykes, Andren, Bourassa and McKibbin28]. The cognitive-affective aspect of HelpA includes assumed feelings such as embarrassment about one’s own hypothetic or actual help-seeking or what others might think about one’s own hypothetic or actual help-seeking for mental problems [Reference ten Have, de Graaf, Ormel, Vilagut, Kovess and Alonso29]. The cognitive-behavioural aspect of HelpA includes help-seeking intentions and people’s willingness to seek help in case of mental problems [Reference ten Have, de Graaf, Ormel, Vilagut, Kovess and Alonso29, Reference Picco, Abdin, Chong, Pang, Shafie and Chua30]. Similar to PersonS and in line with the theory of planned behaviour [Reference Ajzen31, Reference Campion, Bhui and Bhugra9], the cognitive-behavioural, but not the cognitive-affective aspect of HelpA, was related to healthcare utilisation [Reference Mojtabai, Evans-Lacko, Schomerus and Thornicroft32, Reference McEachan, Conner, Taylor and Lawton33].

The different stigmatising attitudes, however, are neither exclusive nor distinct determinants of help-seeking but interact with other determinants, an important one being MHL [Reference Svensson and Hansson34]. MHL is defined as knowledge about mental disorders, including etiological and help-seeking knowledge [Reference Jorm, Korten, Jacomb, Christensen, Rodgers and Pollitt35, Reference Wei, McGrath, Hayden and Kutcher36]. The public’s causal explanations for mental health problems as part of MHL were associated with stigmatising attitudes toward individuals with mental disorders [Reference Reavley and Jorm37]. Of these, biogenetic causal explanations were repeatedly related to more stigmatisation in terms of perceived dangerousness that, in turn, increased WSD [Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer38, Reference Kvaale, Haslam and Gottdiener39].

Despite the wealth of knowledge on single associations between stigma, MHL and help-seeking from predominately cross-sectional studies, at present, little is known about the interplay of the various effects of stigma, biogenetic, and other causal explanations with respect to their influence on healthcare utilisation for mental problems. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, studies of the interrelations between causal explanations and help-seeking attitudes, as well as between help-seeking intentions and healthcare utilisation are still missing. A better integration and extension of these different cross-sectional findings, however, is needed to advance the development of combined information and anti-stigma campaigns and avoid unexpected adverse effects. This will help overcome the two important barriers to adequate and timely mental healthcare utilisation for mental problems [Reference Corrigan, Michaels and Morris41–Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty and Rose44].

Using structural equation modelling (SEM) that enabled us to account for potential correlations and associations between these constructs [Reference Coppens, Van Audenhove, Scheerder, Arensman, Coffey and Costa40], we therefore aimed to disentangle these various interrelations between aspects of stigma and causal explanations, as possibly the most influential aspect of MHL on stigma, on hypothetical help-seeking intentions and, finally, healthcare utilisation for any mental problem at population level.

2. Method

2.1 Study design

Our study is based on the cross-sectional data of an add-on to the ‘Bern Epidemiological At-Risk’ (BEAR) study, a random-selection representative population telephone study in the semi-rural Canton Bern, Switzerland [Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Ruhrmann and Schimmelmann45]. Between June 2011 and June 2015, we recruited participants between 16 and 40 years. We chose this age range because most axis-I mental disorders have their onset after 15 and before 41 years [Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters46]. Besides appropriate age, eligibility criteria were main residency in Canton Bern (i.e. having a valid address in Canton Bern, and not abroad during the assessment period) and an available telephone number. Exclusion criteria included past or present psychosis, and insufficient language skills in German, French, English, or Spanish. To increase response rate, we sent an information letter prior to the first telephone contact with study details and goals.

After each interview, we asked German-speaking participants to enrol in the add-on study and complete a questionnaire on MHL and attitudes. The questionnaires focussed on either depression or schizophrenia and were randomly posted in turn within two days at most after the phone interview. To increase response rate, we reminded participants thrice to complete the questionnaire and offered help in case of difficulties.

The ethics committee at the University of Bern approved the studies. All participants gave informed consent for both studies.

2.2 Measures

In the telephone interview, we assessed socio-demographic variables and current axis-I disorders with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I, [Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Sheehan, Amorim and Janavs48]). Past and/or present healthcare utilisation for mental problems not restricted to mental health professional bodies and irrespective of the intensity of the contact, along with the spontaneously named problems leading to it, was assessed with the WHO Pathways-to-Care questionnaire [Reference Gater, Sousa, Barrientos, Caraveo, Chandrashekar and Dhadphale47].

Adapted from Angermeyer et al. [Reference Angermeyer, Matschinger and Corrigan49], the questionnaire of the add-on study started with an unlabelled vignette (see Appendix to Angermeyer et al. [Reference Angermeyer, Matschinger and Corrigan49]) on either schizophrenia or major depression referred to in subsequent questions. For assessment of causal explanations, participants were asked to rate the 18 causes on a five-point Likert scale from 0 = ‘certainly not a cause’ to 4 = ‘certainly a cause’. For assessment of the cognitive-affective aspect of PersonS, participants were asked to rate 11 stereotyping attributes about the described person on a five-point Likert scale from 0 = ‘certainly not agree with’ to 4 = ‘certainly agree with’. For assessment of the cognitive-behavioural aspect of PersonS, participants were asked to rate their willingness to engage in seven social relationships with the described person (adapted social distance scale developed by Link et al. [Reference Link, Cullen, Frank and Wozniak50]) on a five-point Likert scale from 0 = ‘definitely willing’ to 4 = ’definitely not willing’. Higher values on the PersonS scales indicated stronger stigmatising attitudes. The cognitive-affective aspect of HelpA was assessed based on the response of the participants to the following two questions: ‘how comfortable would you feel talking with a specialist about your personal problems’ (four-point Likert scale from 0 = ‘not at all comfortable’ to 3 = ‘very comfortable’) and ‘how embarrassed would you feel if your friends knew that you seek help for an emotional problem’ (four-point Likert scale from 0 = ‘very embarrassed’ to 3 = ‘not at all embarrassed’). We assessed the cognitive-behavioural aspect of HelpA (i.e., help-seeking intentions) based on the participants potential willingness to seek help from a specialist for an emotional problem (four-point Likert scale from 0 = ‘definitely not’ to 3 = ‘definitely yes’). For both HelpA concepts higher values indicate positive HelpA.

2.3 Statistical analyses

For group comparisons of categorical or non-normally distributed continuous data, we computed χ2-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, respectively. Prior to the structural equation models (SEM), we computed orthogonal exploratory factor analyses (EFA) with varimax rotation on the basis of polychoric correlation matrices for participant’s causal explanations and PersonS, to obtain independent factors. We computed SEMs with the weighted least squares and variance adjusted estimator (WLSMV, [Reference Brown51]) based on diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) for categorical variables [Reference Muthén, Bollen and Long52]. Missing data were deleted listwise. We assessed the model fit with four commonly used indices that were as follows: the χ2 test, the comparative fit index (CFI), the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) including 90%-confidence interval (90%CI). A non-significant χ2-test, CFI ≥ 0.95, SRMR ≤ 0.08, and RMSEA ≤ 0.06 (90%CI should not contain 0.08) indicated good model fit [Reference Kline53, Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen54]. In the evaluation of model fit, we focussed on CFI, SRMR, and RMSEA, because the χ2-test is sensitive to sample size resulting usually in a rejected model in large samples such as ours [Reference Bentler and Bonnet55].

We formed latent variables for causal explanations and for PersonS according to results of the EFA, and for the cognitive-affective aspect of HelpA ‘not embarrassing/feeling comfortable’, to generate the measurement models. Help-seeking intentions and past and/or present healthcare utilisation were observed variables. Following recommendations for confirmatory factor [Reference Acock56], we dropped items with factor loadings ≤0.4 from the analyses. We computed all parameters based on standardisation of latent and manifest variables.

We first tested the hypothesised base model including all likely associations between latent and manifest variables (eFigure 1). Then we dropped latent variables with non-significant associations as well as other non-significant associations from the model. For sensitivity analysis, we analysed the final model in the two subgroups (depression and schizophrenia vignette) separately. Finally, we included socio-demographic variables and axis-I disorder potentially confounding healthcare utilisation. Statistical analyses were done using Stata version 14 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and R (R Core Team) package lavaan [Reference Rosseel57].

3. Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

Of the 2683 representative participants of the telephone study, 2519 spoke German. Of these eligible participants, 1519 returned the questionnaire; thus, the response rate was 60.3% (Fig. 1). There was no indication of a response bias related to the vignette, presence of any current mental disorder, or past and/or present healthcare utilisation for mental problems. However, non-responders were mostly young males with a low education level. All response biases had a small effect size (eTable 1).

Fig. 1. Survey outcome rates of the Bern Epidemiological At Risk (BEAR June/2011–June/2015) telephone and its add-on questionnaire study according to the definitions of the American Association for Public Opinion Research (Ref: Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 9th edition. The American Association for Public Opinion Research. AAPOR; 2016. http://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2017).

Of the responders, 377 (24.8%) reported past and/or present healthcare utilisation for mental problems in the telephone survey (Table 1). Only 49 (3.2%) reported current healthcare contact for mental problems. Healthcare utilisers were more likely older, educated females, currently meeting the criteria for a non-psychotic mental disorder (Table 1).

Table 1 Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of sample.

aaccording to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012 [58]).

baccording to Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

cCramer’s V of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 represent small, medium, and large effect size.

dPearson’s r of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 represent small, medium, and large effect size.

*cell frequency significantly higher or lower than expected with the standardised residuum of cell of >1.96 and of <−1.96, respectively.

Note: sum scores of different axis-I disorders do not add up to current axis-I disorder ‘yes’ due to comorbidity.

3.2 Factors of causal explanations and stigmatising attributes

EFA of the 18 causal explanations resulted in five independent factors: ‘psychosocial stress’, ‘childhood adversities’, ‘biogenetics’, ‘substance abuse’, and ‘constitution/personality’ (eTable 2). ‘Psychosocial stress’ was the main causal explanation for the depicted symptoms, followed by ‘substance abuse’, ‘biogenetics’, ‘childhood adversities’, and ‘constitution/personality’ (eTable 2).

EFA of the 18 items on PersonS led to four independent factors as follows: ‘perceived unpredictability/dangerousness’, ‘wish for social distance' (WSD), “dependent”, and ‘needy’ (eTable 3). Further analyses only considered ‘perceived unpredictability/dangerousness’ and WSD due to their dominance in prior studies [Reference Link, Yang, Phelan and Collins59]. Participants mostly attributed unpredictability to a person with a mental disorder and expressed the strongest WSD with respect to child-care and job-recommendation (eTable 3).

Most participants expressed high help-seeking intentions, i.e. they would likely or certainly seek help in case of mental problems (eFigure 2). Participants anticipated generally feeling comfortable talking to a professional about potential mental problems, and not feeling embarrassed if others knew about the assumed help-seeking (factor ‘pleasant/not embarrassing’) (eFig. 2).

3.3 Associations between causal explanations and attitudes and their influence on healthcare utilisation

Little missing data (between 0.2–1.2% per item) resulted in 10% missing data in total, using the list wise deletion method. The initial model showed a good fit, and most hypothesised stigmatising attitudes and associations became significant (eFig. 3). No significant associations were found between causal explanations related to substance abuse or childhood adversity and ‘perceived unpredictability/dangerousness’ or ‘pleasant/not embarrassing’, and between WSD and help-seeking intentions (eFig. 3). Consequently, we dropped these two latent variables from the model and removed non-significant associations.

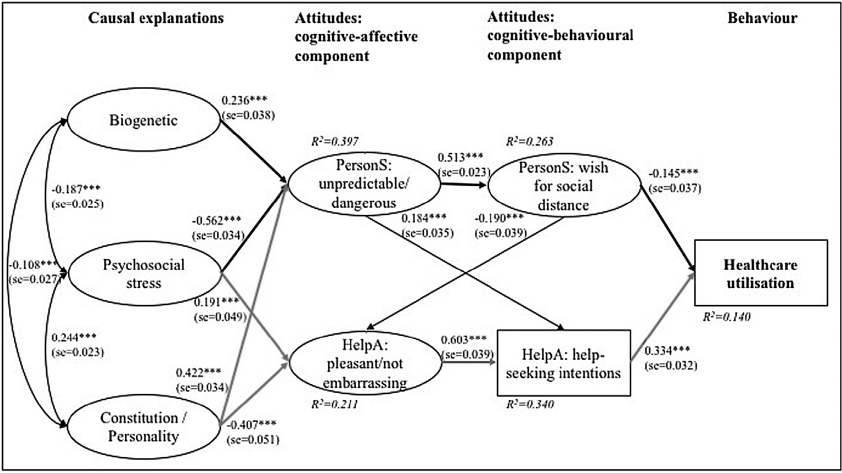

The final resultant SEM had a good model fit and indicated two main paths from causal explanations via attitudes to healthcare utilisation (Fig. 2, Table 2). One path was positive associated with healthcare utilisation and led from high psychosocial stress and low constitution/personality related causal explanations via perceiving help-seeking as pleasant/not embarrassing and help-seeking intentions to more likely healthcare utilisation. The other path was negative associated with healthcare utilisation and led from high biogenetic as well as constitution/personality and low psychosocial stress related causal explanations via strongly perceived unpredictability/dangerousness and a strong WSD to less likely healthcare utilisation. Furthermore, a perception of unpredictability/dangerousness was positive associated with help-seeking intentions, whereas a stronger WSD was negative associated with the perception of help-seeking as pleasant/not embarrassing (Fig. 2).

Table 2 Standardised factor loadings of latent variables from final model and their corresponding standard errors.

**p ≤ 0.001.

a Reference indicator with fixed factor loadings in unstandardised solution.

Fig. 2. Final model of associations between causal explanations, stigmatising attitudes and healthcare utilisation (n = 1375).

Model fit indices: χ2(338) = 1731, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.966; SRMR = 0.055; RMSEA = 0.055 (90%CI = 0.052–0.057). Note: *** p ≤ 0.001; standardised path coefficient and corresponding standard error (in parentheses); explained variance (R2) for each endogenous variable in italics. Rectangles represent observed manifest variables, ovals represent unobserved latent variables; rounded arrows represent covariances; straight arrows represent regressions. Bolt black arrows indicate paths that decreased healthcare utilisation, bolt grey arrows indicate paths that increased healthcare utilisation.

3.4 Sensitivity analyses and influence of sociodemographic and clinical variable

The sensitivity analyses of the influence of the vignettes revealed models of comparable good fit. They differed slightly, especially with respect to the role of biogenetic causal explanations (Fig. 3). These played no significant role in the depression–vignette model. However, compared to the general model, their influence on perceived unpredictability/dangerousness became more pronounced in the schizophrenia-vignette model. The two main paths of the general model remained generally stable for both vignettes; however, for the schizophrenia vignette the association between WSD and healthcare utilisation became non-significant.

Fig. 3. Final model of associations for depression and schizophrenia vignette separately.

Note: *p ≤ 0.05 ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001; standardised path coefficient and corresponding standard error (in parentheses); explained variance (R2) for each endogenous variable in italics. Rectangles represent observed manifest variables, ovals represent unobserved latent variables; rounded arrows represent covariances; solid straight arrows represent significant, dashed straight arrow represents non-significant regression. Results of two models are presented here: MFI, R2 and results of solid arrows relate to reduced model (non-significant paths dropped from model). Result of dashed arrow relates to full model.

To control for potentially confounding variables of healthcare utilisation, we included socio-demographic and clinical variables in an extended SEM (eFig. 4). Although current axis-I disorder, female sex, and higher age were positively associated with healthcare utilisation and slightly increased the explained variance of healthcare utilisation, all paths of the general model (Fig. 2) remained significant at a slightly decreased model fit.

4. Discussion

Our unique, comprehensive community study on the pathways from causal explanations of mental disorders via attitudes towards mental disorders and help-seeking, and help-seeking intentions to healthcare utilisation provides important insights, thereby extending our knowledge on the interplay of previously reported single associations. We identified two major pathways, one that was positively associated with healthcare utilisation for mental problems and another that was negatively associated with it. These pathways were in most parts independent of the clinical picture illustrated in the two vignettes, as well as of sociodemographic variables and presence of a non-psychotic axis-I disorder.

The pathway that was positive associated with healthcare utilisation went from high psychosocial stress and low constitution/personality related causal explanations via pleasant/not embarrassing perception of help-seeking to high help-seeking intentions. Help-seeking attitudes in general (incl. help-seeking intentions) had been related to healthcare utilisation earlier [Reference Schnyder, Panczak, Groth and Schultze-Lutter19]; however, the role of causal explanations was unknown. Interestingly, biogenetic causal explanations that received a strong focus in stigma research, especially for their effect on the attitude towards persons with mental illness [Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer38, Reference Kvaale, Haslam and Gottdiener39], played no significant role in this pathway [Reference Lee, Laurent, Wykes, Andren, Bourassa and McKibbin28]. They only exhibited relatively small negative associations with stress- and constitution/personality-related causal explanations. They have been substituted by constitution/personality related causal explanations having a moderately negative impact on the perception of help-seeking as pleasant/not embarrassing. Jorm and Griffiths [Reference Jorm and Griffiths60] have also reported personal weakness (a main factor of our latent variable ‘constitution/personality’), as opposed to biogenetic causal explanation, to be an important determinant of stigmatising attitudes. In contrast, psychosocial stress-related causal explanations with a moderately positive association with constitution/personality related explanations had a minor positive effect on help-seeking attitudes. In line with the results of previous studies [Reference Mojtabai, Evans-Lacko, Schomerus and Thornicroft32, Reference McEachan, Conner, Taylor and Lawton33], perception of help-seeking as pleasant/not embarrassing was strongly associated with help-seeking intentions, which was moderately associated with healthcare utilisation. The moderate path between intended help-seeking and healthcare utilisation supports the notion that intentions and behaviour are associated [Reference Ajzen31], but not the same. Although most people would recommend seeking help from a professional [Reference Holzinger, Matschinger and Angermeyer61], a much lower proportion actually engaged in it [Reference Wang, Angermeyer, Borges, Bruffaerts, Tat Chiu and De Girolamo7]. Future studies should therefore distinguish between intended help-seeking and healthcare utilisation when examining impact of stigmatising attitudes on help-seeking, particularly if the focus is on promoting early help-seeking.

A surprising finding was the small positive effect of perceived unpredictability/dangerousness on help-seeking intentions. This association seems to depend on the strength of the perceived unpredictability/dangerousness and was only included in the sensitivity analyses for the schizophrenia vignette model [Reference Angermeyer, Matschinger and Corrigan49]. This counterintuitive finding might reflect persons’ wishes to prevent being stigmatised themselves by symptoms like the ones depicted in the vignette, thus voicing stronger intentions to seek help in case of their-own potential mental problems. Further studies looking deeper into this possible link are required.

The pathway that was negative associated with healthcare utilisation went from low psychosocial stress and high constitution/personality related causal explanations as well as biogenetic causal explanations via perceived unpredictability/dangerousness to high WSD. Earlier studies on the impact of causal explanations on stigma had often focussed on biogenetic causal explanations [Reference Kvaale, Haslam and Gottdiener39], while other causal models received less attention. Interestingly, despite supporting a significant moderate role of biogenetic causal explanations, our results indicated a strong role of the commonly neglected psychosocial stress and constitution/personality related causal explanations on stigmatisation of persons with mental disorder. Altogether, our results on causal explanations indicate that causal models related to person factors increase perceived unpredictability/dangerousness while those related to stressful environmental factors decrease it. In line with the results of other studies [Reference Lee, Laurent, Wykes, Andren, Bourassa and McKibbin28, Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer38], perceived unpredictability/dangerousness increased WSD. However, this had a minor negative effect on healthcare utilisation. A recent meta-analysis reported a slightly smaller effect of attitudes towards persons with mental disorder compared to that of attitudes towards help-seeking in the general population, on healthcare utilisation [Reference Schnyder, Panczak, Groth and Schultze-Lutter19]. Furthermore, the higher impact of help-seeking attitudes on healthcare utilisation supports the earlier theories of a strong association between the two [Reference Ajzen31, Reference O'Connor, Martin, Weeks and Ong62]. In the schizophrenia vignette model, this direct link between WSD and healthcare utilisation disappeared. This was surprising in light of the commonly reported greater link of WSD with schizophrenia compared to its link with depression [Reference Angermeyer, Matschinger and Corrigan49]; this was expected to exert a stronger impact on healthcare utilisation.

Contrary to our expectations, we did not find a direct association between WSD and help-seeking intention. However, WSD had a negative impact on the positive pathway because of the perception of help-seeking as potentially embarrassing/unpleasant. Other studies have shown negative effects of WSD on help-seeking intentions [Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer27, Reference Yap, Wright and Jorm63]. However, to the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to differentially assess this relationship, including the perception of help-seeking as potentially embarrassing/unpleasant, as a moderator of help-seeking intentions in one model.

The acknowledgement of two largely independent pathways from causal models via stigmatising attitudes to healthcare utilisation, if replicated in future studies with a prospective design, will be relevant to designing efficient campaigns promoting early healthcare utilisation. These could focus on reducing barriers to healthcare, promoting facilitators of health care utilisation, or both, by differential strategies. In both cases, however, childhood adversity and substance use related causal explanations seem to play a negligible role on stigma-related barriers to healthcare utilisation, at least not in cases of schizophrenia and depression. Our results indicate that these pathways, albeit sharing many features, do differ in some respects. Thus, future studies should also address the question of similarities and differences with respect to different mental disorders; this will improve the focus on common links in general campaigns and address specific features, related to specific risk groups, in special campaigns.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

Despite the two obvious strengths of our study: (1) examining various relevant associations of the pathway from causal models via stigmatising attitudes to healthcare utilisation in one study, and (2) using healthcare utilisation, rather than only hypothetical help-seeking intentions, as an outcome in a randomly selected, representative community sample, some limitations have to be considered. One of the limitations our study shares with other studies [Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko and Bezborodovs13, Reference Schnyder, Panczak, Groth and Schultze-Lutter19] is its reliance on cross-sectional data of a high-income, Western society. We can therefore neither exclude the problem of reversed causation, because past healthcare utilisation might shape a person’s attitudes, nor can we translate our findings to low-income or non-western societies. Another limitation shared with other studies [Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin64, Reference Nederhof65] is the possibility of a response bias towards social desirability. Future studies might use implicit association tests or direct behavioural observations. Furthermore, the small differences between the two vignette groups might indicate an effect of symptoms on healthcare utilisation. An earlier analysis of the first half of participants, however, has shown that, irrespective of the clinical picture, participants’ main spontaneously reported reasons for healthcare utilisation were depressiveness (30%) and anxiety (17%) and related symptoms such as agitation, withdrawal, loss of energy and tension as well as interpersonal problems (27%), which frequently accompany mental disorders [Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Ruhrmann and Schimmelmann66]. As this is in line with other reports on symptomatic reasons for healthcare utilisation for mental problems [Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha and Bryson67], little mental problem or disorder-specific effect on help-seeking was expected, yet should be studied in future and larger studies. The explained variance of the outcome healthcare utilisation was relatively low, because other structural and/or personal barriers [Reference Andrade, Alonso, Mneimneh, Wells, Al-Hamzawi and Borges11–Reference Schnyder, Panczak, Groth and Schultze-Lutter19] will likely contribute to an individuals’ complex decision to seek help and should be considered additionally in future studies. Finally, we strictly focussed on the action of seeking help for mental problems as the starting point of adequate healthcare provision for mental problems irrespective of the type of point-of-contact and of its consequences in terms of subsequent support or referral pathways, which will also be crucial in providing early, adequate help and improve global mental health on the population level. Thus, our outcome healthcare utilisation cannot be equalled to professional mental health treatment, this limiting the impact of past healthcare utilisation on stigma and MHL. Further discussion of strengths and limitations of the study design incl. validity of assessments and choice of age range can be found elsewhere [Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Ruhrmann and Schimmelmann45].

In our sample, we detected a small response bias in favour of female sex, higher age, and higher education. Since only few studies have reported potential response biases [Reference Gronholm, Thornicroft, Laurens and Evans-Lacko68], we cannot estimate if other similar studies share these biases. However, they are frequently reported in general population studies [Reference Cull, O'Connor, Sharp and Tang69, Reference Guyll, Spoth and Redmond70]. Education, age, and sex had no significant impact on our outcome, thus these small biases are likely to be negligible.

4.2 Conclusion

Our unique study indicated the presence of two largely independent pathways from causal models via stigmatising attitudes to healthcare utilisation. The positive pathway included help-seeking attitudes, the negative pathway included attitudes towards persons with mental disorder. Interestingly, in both pathways, biogenetic causal models played only a minor role, indicating that other causal explanations should be considered equally in future studies. In line with the theory of planned behaviour [Reference Ajzen31, Reference Ajzen71], future studies should distinguish between help-seeking intentions and healthcare utilisation. They might additionally take past behaviours (e.g. past treatment) into account when examining influencing factors such as attitudes and causal explanations. Furthermore, our sensitivity analyses indicated that, while mental disorders might share certain crucial features in attitude-related barriers and facilitators, they might also be associated with distinct features that could be relevant for disorder-specific campaigns.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help and input of following researchers (in alphabetical order): L. Rietschel and S.J. Schmidt.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.