1. Introduction

With an estimated prevalence of 0.03% in clinical samples, delusional disorder (DD) has been traditionally considered a rare psychiatric condition [Reference Kendler1]. Despite more recent reports of prevalence rates as high as 0.18% in general population samples [Reference Perala, Suvisaari, Saarni, Kuoppasalmi, Isometsa and Pirkola2], empirical research on DD is sparse relative to other psychotic disorders. Current diagnostic criteria for delusional disorder [3] are still grounded on Kraepelin’s concept of paranoia, defined as a chronic, systematized delusional condition with no cognitive deterioration or hallucinations, unlike schizophrenia (dementia praecox) [Reference Kraepelin4]. Findings regarding neurocognition in patients with DD have been controversial so far, with some studies reporting poorer attention and verbal learning and memory [Reference Leposavic, Leposavic and Jasovic-Gasic5–Reference Ibanez-Casas and Cervilla7], executive functioning and working memory [Reference Ibanez-Casas, De Portugal, Gonzalez, McKenney, Haro and Usall6] or visuo-spatial ability [Reference Hardoy, Carta, Catena, Hardoy, Cadeddu and Dell'Osso8, Reference Grover, Nehra, Bhateja, Kulhara and Kumar9] in patients with DD as compared with healthy controls, and others not finding any significant differences in neuropsychological performance [Reference Conway, Bollini, Graham, Keefe, Schiffman and McEvoy10, Reference Bommer and Brune11]. Most of these studies are limited by their sample size, which might preclude detecting significant differences. Still, some evidence suggests the presence of cognitive deficits in DD similar to those found in schizophrenia, but possibly subtler [Reference Ibanez-Casas and Cervilla7, Reference Hardoy, Carta, Catena, Hardoy, Cadeddu and Dell'Osso8, Reference Tuulio-Henriksson, Perälä, Saarni, Isometsä, Koskinen and Lönnqvist12]. This is consistent with a recent study comparing psychopathological dimensions in patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and DD. Scores in the cognitive dimension in DD suggested some degree of cognitive impairment, though significantly lower than that found in both schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder [Reference Munoz-Negro, Ibanez-Casas, de Portugal, Ochoa, Dolz and Haro13].

Diagnostic criteria for DD state that, apart from the delusion or its ramifications, functioning is not markedly impaired in delusional disorder (DD) [3]. To our knowledge, no previous studies have empirically validated this criterion and explored whether cognitive deficits and symptom dimensions might have an impact on functionality in DD above and beyond the impact of the paranoid idea and its clinical correlates. Considering that neurocognition is one of the most replicated predictors of functional outcomes in schizophrenia [Reference Green14], we sought to test the hypothesis that neuropsychological performance and cognitive symptoms will be associated with psychosocial functioning and self-perceived functional impairment or disability in DD. In keeping with evidence for a mediation effect of clinical symptoms between neuropsychological performance and functionality in schizophrenia [Reference Ventura, Hellemann, Thames, Koellner and Nuechterlein15], we additionally aimed to explore whether the effect of neuropsychological performance on functionality might be mediated by clinical dimensions in DD. Finally, considering the dearth of previous studies assessing correlates of functionality in DD, we aimed to test whether neurodevelopmental, premorbid and clinical characteristics of the condition might also impact functioning and self-perceived disability in DD.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

We enrolled eighty-six patients with a diagnosis of DD confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) [Reference First16] from five community mental health centers run by Sant Joan de Déu-Mental Health Services (SJD-MHS) in Barcelona, Spain, in a cross-sectional study assessing clinical, neuropsychological and functional characteristics of DD. The inclusion criteria were: (a) a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of DD confirmed with the SCID-I, (b) age 18 years or older, (c) residence in the catchment area of SJD-MHS and (d) at least one outpatient visit during the six months preceding the beginning of the study. The exclusion criteria were: (a) clinical diagnosis of mental retardation, (b) illiteracy, and (c) poor command of the Spanish language. The Ethics Committee of SJD-MHS approved the study and all patients gave written informed consent after full explanation of the study procedures. For the purposes of this study, we only included participants with available neurocognitive data (N = 75).

2.2. Clinical and functional assessment

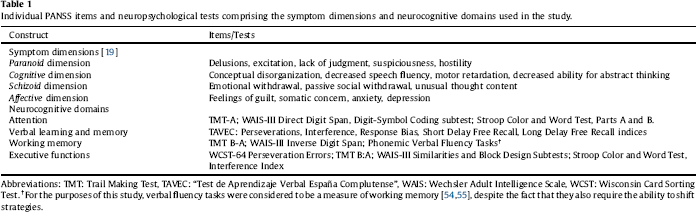

We confirmed DD clinical diagnoses using the psychosis module of the SCID-I [Reference First16]. Using Module B of the same instrument we assessed the presence and type of delusions and hallucinatory behavior (i.e. tactile, olfactory, or non-prominent auditory, visual or gustatory hallucinations related to the delusional theme, not fulfilling criterion A for schizophrenia and of less than one week of duration). We assigned patients to one of seven DD DSM-IV types (persecutory, jealous, somatic, erotomaniac, grandiose, mixed, and not otherwise specified). We assessed psychotic and general psychopathology using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia (PANSS) [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler17, Reference Peralta and Cuesta18]. Since previous symptomatic dimensions obtained by factor analysis of the PANSS have been based on schizophrenia or mixed samples, we calculated scores for four symptomatic dimensions resulting from a previous factor analysis in this DD sample (see Table 1) [Reference de Portugal, Gonzalez, del Amo, Haro and Diaz-Caneja19]. We also calculated mean factor scores based on Lindenmayer’s five-factor solution previously validated in schizophrenia (Positive, Negative, Cognitive, Depressive and Excitement) [Reference Lindenmayer, Brown, Baker, Schuh, Shao and Tohen20].

Global functioning was assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale. The GAF is a clinician-rated scale based on a continuum between mental health and mental disease assessing psychological, social and occupational functioning, with scores ranging from 1 to 100, where higher scores represent higher levels of functioning [21]. We measured self-perceived functional impairment with the Spanish version of Sheehan’s Disability Inventory (SDI) [Reference Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan and Raj22, Reference Bobes, Badia, Luque, Garcia, Gonzalez and Dal-Re23]. The SDI is a self-report instrument that assesses functional impairment in three inter-related areas: work, social and family life. A global dimensional measure of self-perceived global functional impairment or disability can be calculated by summing the scores obtained in each of these three areas, with global scores ranging from 0 to 30. The SDI has shown good sensitivity and specificity in patients with several mental conditions [Reference Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan and Raj22, Reference Bobes, Badia, Luque, Garcia, Gonzalez and Dal-Re23].

We assessed treatment adherence with the Bäuml Treatment Adherence Scale [Reference Bäuml, Kissling and Pitschel-Walz24]. This is a clinician-rated instrument that scores adherence using a 4-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 (very good adherence) to 4 (poor adherence) [Reference Gonzalez-Rodriguez, Estrada and Monreal25]. Adverse experiences before age 18 were assessed using modified questions of the Conflict Tactics Scale [Reference Straus and Gelles26]. We assessed axis-I comorbidity with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) for DSM-IV [Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller27, Reference Bobes28] and premorbid personality disorder with the Standardized Assessment of Personality [Reference Mann, Jenkins, Cutting and Cowen29]. A custom questionnaire was used to collect additional demographic data and clinical variables such as age at onset, duration of illness, treatment delay (i.e. time elapsed from the onset of the first psychotic symptom to the first contact with services), psychotropic treatment, type of onset, course, premorbid auditory deficit, premorbid substance use disorders, and developmental delay. Further details on the clinical assessment are available elsewhere [Reference de Portugal, Gonzalez, del Amo, Haro and Diaz-Caneja19].

A master’s-level clinical neuropsychologist trained in neuropsychological standardized testing procedures, assessment interview techniques, and in the administration of the diagnostic, psychopathological, and functioning scales used in this study evaluated all patients.

Table 1 Individual PANSS items and neuropsychological tests comprising the symptom dimensions and neurocognitive domains used in the study.

2.3. Neuropsychological assessment

We administered a comprehensive battery of tests assessing four neuropsychological domains pertinent to functioning in patients with psychosis: attention, verbal learning and memory, working memory, and executive functions (see Table 1) [Reference Green, Kern, Braff and Mintz30, Reference Green, Nuechterlein, Gold, Barch, Cohen and Essock31]. Neuropsychological assessment was performed in patients considered to be clinically stable by their treating clinicians. We standardized test scores using demographically corrected T scores based on the test manuals and obtained scores for each domain by computing the mean of the tests addressing each domain. We estimated pre-morbid IQ with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale vocabulary subtest (WAIS-III) [Reference Wechsler32].

2.4. Statistical analysis

We analyzed the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample using descriptive statistics (frequencies or mean and SD, as appropriate). Pearson correlation coefficients or Student’s t tests were computed to assess the relationship of clinical factors, symptomatic dimensions and neuropsychological performance with psychosocial functioning and self-perceived disability, and between neuropsychological domains and symptomatic dimensions. False discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons (100 analyses) was implemented using a Benjamini-Hochberg method. The percentage of tolerated false positives was 5% (q < 0.05).

We used two sets of hierarchical linear regression models to assess the association of demographic, clinical variables, symptom dimensions (Paranoid, Cognitive, Schizoid, and Affective) and the four neuropsychological domains (attention, verbal learning and memory, working memory and executive functions) with psychosocial functioning and self-perceived disability, respectively. First, we entered demographic variables (age, sex, years in education, civil status and living arrangement). Then we entered clinical variables showing an association at a p <.200 [Reference Mickey and Greenland33] uncorrected threshold in the bivariate analyses with each of the main outcome variables. Since treatment delay and mean daily antipsychotic dose were highly skewed, we applied a log-transformation. In the third and fourth stages, we entered scores in the four symptom dimensions and four neurocognitive domains, respectively. At each step, we entered those variables found to be significant in the previous model, and we calculated the change in adjusted r2 from the previous model. We repeated these analyses using the factor scores based on a previous five-factor solution in schizophrenia. Additional linear regression analyses were conducted with the three dimensions of the SDI (work, social and family) as outcome measures.

We used path analysis in Stata to explore a potential mediation effect of symptom dimensions on the association between neuropsychological domains and functioning and disability, including the neuropsychological and symptom dimension variables and the covariates found to be significant in the final linear regression models for each outcome. We used maximum likelihood estimation with bootstrapping (10,000 bootstrap samples) to estimate the parameters of the model with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p value <0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 and Stata 14.

3. Results

Table 2 shows the demographic, clinical and neuropsychological characteristics of the sample and their bivariate associations with functioning, as measured with the GAF, and self-perceived disability, as measured with the SDI. Scores in the Paranoid and Cognitive dimensions were significantly associated with the GAF but not with the SDI. Scores in verbal memory were significantly correlated with scores in the GAF and the SDI, while scores in executive function were only significantly correlated with the SDI. After applying an FDR-adjustment for multiple comparisons, the correlations of the Paranoid and Cognitive dimensions, and verbal memory with scores in the GAF, as well as between scores in the SDI and executive function remained significant (see Table 2).

The Cognitive dimension was negatively correlated with attention (r=-0.326, p =.004), verbal memory (r=-0.316, p =.006) and working memory (r=-0.383, p =.001), that is, higher scores in the Cognitive dimension, indicative of more severe cognitive symptoms, were associated with lower performance in these domains. On the contrary, the Affective dimension was positively correlated with verbal learning and memory (r = 0.266, p =.022) and working memory (r = 0.238, p = 0.040). We found no significant associations between the Paranoid and Schizoid dimensions and any neuropsychological domains.

In the final hierarchical linear regression model, lower psychosocial functioning, as measured with the GAF, was significantly associated with older age, being single, higher scores in the Paranoid and Cognitive symptom dimensions and poorer performance in verbal learning and memory (F = 21.26, p <.001, r 2 = 0.581; see Table 3). Verbal learning and memory accounted for 7.5% of the explained variance in the model. Exploratory mediation analyses showed that the effect of verbal memory on psychosocial functioning in the final model could be partially mediated by its effect on the Cognitive symptom dimension (proportion mediated = 27.2%; see Fig. 1).

Higher self-perceived functional impairment, as measured with the SDI, was significantly associated with younger age, being male, higher number of adverse experiences during childhood and adolescence, history of any lifetime inpatient admission, presence of a psychosocial precipitating factor at illness onset and lower performance in the verbal learning and memory and executive function domains (F = 11.25, p <.001, r 2 = 0.499; see Table 4). Verbal learning and memory and executive functions accounted for 9.9% and 3.1% of the explained variance in the SDI, respectively. Since we detected no significant effect of symptom dimensions on the SDI, we did not perform mediation analyses for this outcome. Linear regression analyses including disability in the work, family and social areas as outcome measures identified younger age and poorer verbal memory and learning as common predictors of self-perceived disability in the three areas (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

We identified a similar set of predictors of global functioning and self-perceived disability in the linear regression models using symptom dimensions based on Lindenmayer’s five-factor solution of the PANSS, previously validated in schizophrenia (see Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the effect of neuropsychological performance on global functioning and self-perceived disability in patients with DD. We found that the cognitive symptom domain and verbal memory performance affect global functioning in patients with DD above and beyond the severity of the paranoid idea. Poorer verbal memory, as well as executive functioning, is also associated with self-perceived functional impairment. This study questions with empirical findings the widespread assumption that functionality in DD is affected only by the delusion or its ramifications [3]. Our findings also suggest that, similarly to patients with schizophrenia [Reference Green14], cognition might be associated with functionality in patients with DD.

Table 2 Bivariate associations of demographic and clinical variables, symptom dimensions and neuropsychological performance with psychosocial functioning and self-perceived disability in delusional disorder.

a Premorbid IQ shown as T-score.

In keeping with current diagnostic criteria [3], the Paranoid dimension, which includes the nuclear symptoms of paranoia (delusions, suspiciousness, hostility, excitation and lack of insight) and can be conceptualized as an appropriate proxy of “the delusional idea and its ramifications” in DD, accounted for the greatest amount of the explained variance in the GAF. However, we also found that the Cognitive symptom dimension and verbal memory were independently associated with functioning, as measured with the GAF, jointly accounting for variance comparable to that accounted for by the Paranoid dimension. We also found a similar effect of verbal memory and an additional effect of executive functions on self-perceived disability as measured with the SDI, with no significant effect of the symptom dimensions on this outcome. We also found similar results for the Positive and Cognitive clinical dimensions using a five-factor solution of the PANSS, which has been previously validated in schizophrenia. The finding of a significant association between the symptom dimensions and the GAF is not surprising, considering that the GAF takes into account clinical symptoms in its rating, an issue that has led to previous criticism of the scale [Reference Gold34]. Nevertheless, even if the total amount of variance explained by verbal memory in both models is relatively small, we found a comparable effect on both functional outcomes, suggesting that verbal memory might be an independent contributor to both clinician-rated and self-perceived functioning in DD, even after accounting for the effects of paranoid and cognitive symptoms.

Table 3 Hierarchical linear regression models assessing the association of demographic and clinical variables, symptom dimensions and neuropsychological performance with psychosocial functioning in delusional disorder.

a p <.05.

b p <.01.

c p <.001.

Previous studies have found that both verbal memory and executive functions can be impaired in patients with DD relative to healthy controls [Reference Leposavic, Leposavic and Jasovic-Gasic5–Reference Ibanez-Casas and Cervilla7], suggesting the presence of dysfunction involving the prefrontal cortex and temporolimbic structures, an idea compatible with recent neuroimaging findings in DD [Reference Oflaz, Akyuz, Hamamci, Firat, Keskinkilic and Kilickesmez35, Reference Vicens, Radua, Salvador, Anguera-Camos, Canales-Rodriguez and Sarro36]. In keeping with our findings, these neurocognitive domains have also been found to significantly affect functional outcomes in schizophrenia [Reference Green14] and other psychotic disorders, such as bipolar disorder [Reference Martinez-Aran, Vieta, Torrent, Sanchez-Moreno, Goikolea and Salamero37]. Deficits in encoding and retrieval of verbal information and in cognitive flexibility can be associated with impairments in social cognition and reduced capability to acquire social skills and implement social problem-solving strategies, leading to reduced social competence and functional impairment [Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder38]. Verbal learning and memory seems to be one of the neurocognitive domains more amenable to cognitive remediation approaches, which seem to improve neuropsychological and global functioning in patients with schizophrenia [Reference Wykes, Huddy, Cellard, McGurk and Czobor39]. Considering the limited response of DD to current pharmacological options (only about one third of patients show good responses to medication) [Reference Munoz-Negro and Cervilla40] or to psychological strategies targeting the paranoid idea such as cognitive-behavioral approaches [Reference Skelton, Khokhar and Thacker41], tailored cognitive remediation or training strategies targeting verbal memory, and possibly abstraction/flexibility processes could provide functional benefits in this clinical population. These strategies could be especially helpful in the subgroup of patients with DD showing greater cognitive deficits [Reference Gonzalez-Rodriguez, Molina-Andreu, Penades, Bernardo and Catalan42]. Alternatively, compensatory approaches or social skill training reducing the demands on these cognitive functions might also be useful for improving functionality in DD, as previously suggested for schizophrenia [Reference Green, Kern, Braff and Mintz30].

Fig. 1. Path model for the association between verbal memory, cognitive symptoms and global functioning.

We found that the Cognitive symptom dimension (comprising the items conceptual disorganization, decreased capacity for abstract thinking, decreased speech fluency and motor retardation) was negatively correlated with attention, working memory and verbal learning and memory, along the lines of previous findings in schizophrenia [Reference Ventura, Thames, Wood, Guzik and Hellemann43, Reference Cameron, Oram, Geffen, Kavanagh, McGrath and Geffen44]. Deficits in these domains might result in alterations in prefrontal-cortex mediated storage and information processing tasks, leading to cognitive and disorganization symptoms and functional impairment [Reference Cameron, Oram, Geffen, Kavanagh, McGrath and Geffen44]. Indeed, we found that the effect of verbal memory on global functioning could be partially mediated through its effect on cognitive symptoms in the exploratory mediation analyses. On the contrary, we found no significant associations between any neuropsychological domains and the Paranoid dimension, which was also consistent with previous findings on delusions or on positive symptoms of schizophrenia [Reference Ventura, Thames, Wood, Guzik and Hellemann43].

We did find an association between male sex and lower functionality and higher disability in most models. Although a previous longitudinal study did not find significant differences in disability between male and female patients with DD [Reference Wustmann, Pillmann and Marneros45], our finding is consistent with previous evidence in schizophrenia [Reference Grossman, Harrow, Rosen and Faull46]. A possible mechanism underlying the association between female sex and better psychosocial functioning might be better female performance in verbal learning and memory, consistent with previous reports in schizophrenia [Reference Mendrek and Mancini-Marie47]. In our sample, female patients with DD showed significantly better scores in verbal learning and memory than males (mean score: 38.58 ± 10.74 in males, vs. 46.94 ± 90.70 in females, t=-3.409, p =.001), with no significant differences in any other cognitive domains. We found an opposite effect of age on functionality and self-perceived disability. While older age was associated with impaired psychosocial functioning, younger patients reported higher self-perceived disability. This may reflect greater discrepancy between expectations and achievements in younger people, leading to greater self-perception of functional impairment.

Global functioning was also significantly associated with non-prominent auditory hallucinations in the linear regression models, as well as with family history of schizophrenia and history of premorbid neurodevelopmental difficulties in the bivariate associations. Even if most of these variables were not significant predictors in the final models, they might delineate a subtype of DD more closely related to schizophrenia, with greater functional impairment. Contrary to previous findings in schizophrenia, where duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) constitutes one of the most replicated predictors of functional outcomes [Reference Penttila, Jaaskelainen, Hirvonen, Isohanni and Miettunen48], we did not detect a significant effect of treatment delay on psychosocial functioning or self-perceived disability in the final regression models. The different nature, form of onset and usual course of both psychotic disorders might underlie these differences. Alternatively, it has been previously noted that the impact of DUP on some outcomes might be more marked or only noticeable in samples with relatively short DUP [Reference Boonstra, Klaassen, Sytema, Marshall, De Haan and Wunderink49]. The fact that our sample had relatively long delays before treatment could have precluded finding a significant association between DUP and functioning in the regression analyses.

This work has numerous limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study and does not allow for inferring causality. Second, we relied on the GAF as the main measure of functionality. Even if the limitations of the GAF have been previously acknowledged [Reference Gold34], it is a well-validated instrument that is still extensively used in clinical and research settings. We also complemented the GAF with a self-report measure of functional impairment and found comparable results for the effect of verbal memory on self-perceived functional impairment in the social, family and work areas. Third, we did not include any measures of social cognition or metacognition, which have been found to affect functionality in people with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders [Reference Green14] and could mediate the effect of neurocognition on functional outcomes [Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder38, Reference Martinez-Dominguez, Penades, Segura, Gonzalez-Rodriguez and Catalan50]. Since social cognition deficits seem to be present in patients with delusional disorder [Reference Abdel-Hamid and Brune51], future studies should specifically assess the association of social cognition and metacognition with functionality in this population. Fourth, this was a clinical sample recruited among outpatients attending mental health services in a rural area, with low educational attainment and a mean duration of illness of 14 years, and might thus not be representative of DD in the community. Fifth, even if this is a relatively large sample for DD considering the relatively low prevalence and small numbers of patients seeking treatment, sample size might have affected our results and did not allow us to perform specific analysis in subtypes of DD. Sixth, the correlation coefficients in the mediation analyses are small, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions. Further studies in larger samples are warranted to replicate these findings. Finally, we did not include a control group and cannot rule out that the associations found between neurocognition and functionality might reflect a general process not specific to DD. Nonetheless, our findings are consistent with previous reports in schizophrenia, and there is some evidence that these associations might be, to some extent, specific to psychotic disorders [Reference Mueser, Pratt, Bartels, Forester, Wolfe and Cather52, Reference Zanello, Perrig and Huguelet53].

Table 4 Hierarchical linear regression models assessing the association of clinical variables, symptom dimensions and neuropsychological performance with self-perceived disability in delusional disorder.

a p <.05.

b p <.01.

c p <.001.

The limitations notwithstanding, this study constitutes a first attempt to assess clinical and cognitive correlates of functionality in DD by combining both a clinician-rated and a subjective measure of functionality, as well as a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological measures. We found that cognitive symptoms and poorer performance in verbal memory may have an effect on global functioning in DD above and beyond the impact of the delusional idea. This suggests a potential role for cognitive remediation and other cognitive interventions in the management of patients with DD. Considering the limited efficacy of current treatment strategies for DD, the identification of neurocognitive domains more strongly associated with functional impairment could help guide tailored interventions to improve functional prognosis in this clinical population.

Funding acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI02/01813, PI09/01671, PI12/1303), co-financed by ERDF Funds from the European Commission, “A way of making Europe”, CIBERSAM, Andalucía Regional Government (CTS 1686), Madrid Regional Government (S2017/BMD-3740), European Union Seventh Framework Program [FP7-HEALTH-2009-2.2.1-2-241909 (project EU-GEI); FP7-HEALTH-2009-2.2.1-3-242114 (project OPTiMiSE); FP7- HEALTH-2013-2.2.1-2-603196 (project PSYSCAN); FP7- HEALTH-2013-2.2.1-2-602478 (project METSY)], European Union H2020 Program under the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (grant agreement No 115916; project PRISM) and Fundación Familia Alonso. The funding sources played no role in the writing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Covadonga M. Díaz-Caneja has previously held grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and from Fundación Alicia Koplowitz. Celso Arango has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants from Acadia, Abbot, AMGEN, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Caja Navarra, CIBERSAM, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Fundación Alicia Koplowitz, Forum, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Gedeon Richter, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Merck, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Ministerio de Sanidad, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Mutua Madrileña, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Shire, Schering Plough, Sunovio and Takeda. The rest of the authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the doctors, nurses, and administrative staff of Sant Joan de Déu -Serveis de Salut Mental for their invaluable collaboration.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.09.010.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.