Introduction

Solidarity is and always has been a fundamental value underlying the process of European integration (Sangiovanni, Reference Sangiovanni2013: 213). However, for decades, the meaning of the term and the nature of transnational policies associated with solidarity remained rather vague. This situation changed involuntarily since the late 2000s. The European Union (EU) had to face numerous consecutive economic and political crises, which turned out to be severe tests but also catalysts for renewed discussions concerning solidarity among member states. Throughout the European Economic Crisis,Footnote 1 the EU was divided over its political course to solve economic and financial difficulties. Besides the Greek referendum on bailout conditions in 2015, citizens had little direct say when it came to the implementation of EU-wide solidarity mechanisms. Instead, EU and national parliamentarians had a strong impact on intra-EU redistribution policies.

So far, only a few publications have investigated politicians’ positions on transnational solidarity in the years of the European Economic Crisis (Closa and Maatsch, Reference Closa and Maatsch2014; Maatsch, Reference Maatsch2014, Reference Maatsch2016) or analyzed the decisions of national governments at that time (for instance Târlea et al., Reference Târlea, Bailer, Degner, Dellmuth, Leuffen, Lundgren, Tallberg and Wasserfallen2019). These studies, however, focus on parliamentary debates or votes instead of going deeper and studying the underlying attitudes of politicians and their individual willingness to support transnational solidarity within the EU. A study by Basile and colleagues (Reference Basile, Borri, Verzichelli, Cotta and Isernia2020) constitutes and interesting exception by using survey data of political elites, which provides some initial insights into individual politicians’ preferences for transnational solidarity.

In this paper, we also take up this perspective arguing that analyzing preferences concerning transnational solidarity on the level of individual politicians provides crucial insights for (at least) two reasons. First, a more in-depth understanding of political elites is essential as it allows us to better grasp the quality of representation at the level of preferences and how these preferences are generated. To contribute to this research interest, our study is guided by the question whether the political elite’s preferences for transnational solidarity are driven by similar considerations than those of the citizenry elaborated in previous research. Second, drawing on insights from public opinion research also enables us to identify and further investigate contextual factors that promote or inhibit the relevance of certain attitudes for politicians’ transnational solidarity preferences. Following this, our second research question asks how the relationship between attitudes and preferences is moderated by contextual factors and what this means for the comparative importance of these sets of factors.

We answer these research questions using data provided by the second module of the Comparative Candidates Survey (CCS, 2020) in place from 2013 to 2018 and the 2014 European Candidate Study (GLES, 2017). We combine this survey data with information on parties, public opinion, and the economic situation of a country. In total, we cover a quite heterogeneous group of nine EU member states (Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, and the UK). To be more precise, we can rely on data for almost 4000 politicians running for office in 12 elections for a total of more than 50 different political parties. The vast number of politicians as well as the very different parties and national contexts provide – with all necessary caution – valid and reliable findings increasing our understanding of this important aspect of representative democracy.

We run multilevel linear regression analyses to validate our theoretical arguments and to test our hypotheses. Indeed, politicians’ attitudes toward socioeconomic and EU issues determine preferences for transnational solidarity – with more left-wing and more pro-European politicians being more in favor of solidarity measures. We also find that contextualization matters: if the receiving state is held responsible for its economic crisis, solidarity levels decrease. At the same time, when the politician’s own country is facing economic problems, we see significantly higher levels of support. Finally, and in addition to these direct effects, we find that the impact of attitudes on preferences is moderated: differences in attitudes only play a role if politicians perceive the receiving state as being responsible for its economic crisis. Similarly, different attitudes do not lead to different preferences regarding transnational solidarity if national economic performance is weak in the respondent’s country.

This paper makes two contributions to the literature. First, our findings on the relation between general attitudes and preferences for transnational solidarity are similar to those of former studies on popular attitudes. Thinking about representation and accountability in democratic systems, we interpret this as an encouraging sign. Second, our analyses reveal that the relation between attitudes and preferences is not universal but depends on politicians’ environment. This aspect is particularly relevant against the background of strongly heterogeneous contexts within the EU and thinking about developments over time.

Transnational solidarity and the European economic crisis

In broad and general terms, when we refer to solidarity within a political community, we talk about ‘the preparedness to share resources with others by personal contribution to those in struggle or in need and through taxation and redistribution organised by the state’ (Stjernø, Reference Stjernø2004: 2). For the EU, even though numerous treaties mention solidarity between member states, the term still lacks a precise definition in public as well as scientific debates (Kontochristou and Mascha, Reference Kontochristou and Mascha2014; Pantazatou, Reference Pantazatou2015).

In their research on solidarity in the EU, Gerhards and colleagues (Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019) define European solidarity as ‘a form of solidarity that goes beyond nation state containers and reflects a solidarity with other (European) countries and their citizens’ (Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019: 18). We follow this definition but use the term transnational solidarity when referring to measures that are meant to bring relief during the European Economic Crisis, as this term has frequently been used when focusing explicitly on the level of individuals (Ciornei and Recchi, Reference Ciornei and Recchi2017; Baute et al., Reference Baute, Abts and Meuleman2019).

Scholarly work on solidarity within the EU during the European Economic Crisis focuses on different actors.Footnote 2 For representative democracies, we can distinguish between demand- and supply-side actors embedded in a specific institutional setting. On the demand-side, there are voters and interest groups, while the supply-side refers to parties and politicians. These actors find themselves in different relationships (Katz, Reference Katz2014). Citizens, on the one hand, influence the supply-side, but citizens’ preferences are also shaped and structured by demand-side actors (for instance Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Hobolt and de Vries, Reference Hobolt and de Vries2015). Politicians, on the other hand, set the party’s political course, but in return must also adapt their stances and behavior, i.e., they follow the prescribed party discipline (Bøggild, Reference Bøggild2020). At the same time, parties form governments and thereby shape policies, which are supposed to represent the interests of their voters, but without a doubt have an impact on the society at large.

A number of studies have been published mapping the macro level of European solidarity on the supply-side, that is, the reactions of governments, states, and political institutions (for instance, Frieden and Walter, Reference Frieden and Walter2019; Târlea et al., Reference Târlea, Bailer, Degner, Dellmuth, Leuffen, Lundgren, Tallberg and Wasserfallen2019; Wasserfallen et al., Reference Wasserfallen, Leuffen, Kudrna and Degner2019). However, the research strand that dominates the field examines public support for EU redistribution policies (among others Lengfeld et al., Reference Lengfeld, Schmidt and Häuberer2015; Lahusen and Grasso, Reference Lahusen, Grasso, Lahusen and Grasso2018; Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019). Most of these studies analyzed the preconditions for support of fellow EU states and named European identity (Ciornei and Recchi, Reference Ciornei and Recchi2017; Verhaegen, Reference Verhaegen2018), cosmopolitanism (Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Ciornei and Recchi, Reference Ciornei and Recchi2017; Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Solaz and van Elsas2018; Kleider and Stoeckel, Reference Kleider and Stoeckel2019), economic orientation (Kleider and Stoeckel, Reference Kleider and Stoeckel2019), and support for EU membership (Lahusen and Grasso, Reference Lahusen, Grasso, Lahusen and Grasso2018) as motivations.

In contrast, only few publications have investigated the positions of parties or politicians on solidarity measures, which severely limits our understanding of elite preferences. Furthermore, these studies more or less all focus on political parties and rely on parties’ media content (Bremer, Reference Bremer2018) or on parliamentary debates (Closa and Maatsch, Reference Closa and Maatsch2014; Maatsch, Reference Maatsch2014, Reference Maatsch2016). Despite providing important findings, these studies do not allow straight-forward conclusions about preferences of politicians or the determinants of these preferences. Votes in parliament, plenary contributions, and media appearances are strongly affected by party discipline, which creates problematic levels of distortion.

While a lack of studies on politicians’ preferences concerning transnational solidarity seems problematic per se, it becomes an even bigger issue thinking about political parties in modern democracies. Obviously, political parties rely on their internal organization, but they also rely heavily on their personnel when it comes to fulfilling their role in the democratic process (Gunther and Diamond, Reference Gunther and Diamond2003). Politicians are crucial in communicating with citizens, either directly or via the media (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2000; Römmele, Reference Römmele2003; Matsubayashi, Reference Matsubayashi2013). Depending on the electoral system, individual politicians – or, more precisely, their background and policy positions – are the main focus of citizens’ voting decisions (e.g., Huckfeldt and Sprague, Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1992). Even in less candidate-centered electoral systems, politicians are the face of a party and constitute the group of individuals from which representatives are selected (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2000).

Proceeding from there, we argue that taking a closer look at individual politicians’ preferences is relevant for (at least) two reasons: The first reason relates to the issue of representation. Whether or not the general public agrees with political decisions concerning transnational solidarity or whether there is at least a correspondence in preference formation between voters and representatives of their party is crucial for the quality of a representative democracy. If citizens do not agree with the behavior of political elites, this can result in voter shifts or even decreasing levels of democratic satisfaction. While governments and parties are important actors in representative democracies, they are neither unitary actors nor the only relevant actors on the supply side of politics. Understanding preference formation regarding transnational solidarity of individual politicians and comparing the degree of congruence of these processes to respective patterns in the citizenry can greatly increase our understanding of representational quality in times of crisis.

The second reason refers to the relative importance of attitudes, on the one hand, and contextual and environmental factors, on the other hand, for political elites’ policy preferences. We build on the work of Bartels (Reference Bartels, MacKuen and Rabinowitz2003), Zaller (Reference Zaller1992), and others to distinguish between general attitudes and specific preferences for transnational solidarity that are influenced by these general attitudes. Importantly, research has shown that this relationship depends on various contextual and environmental factors (e.g., Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992; Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Kotler-Berkowitz and Swaine1998; Bartels, Reference Bartels, MacKuen and Rabinowitz2003) – also concerning transnational solidarity of citizens (see Lengfeld et al., Reference Lengfeld, Schmidt and Häuberer2015; Lahusen and Grasso, Reference Lahusen, Grasso, Lahusen and Grasso2018; Vasilopoulou and Talving, Reference Vasilopoulou and Talving2020). Looking at individual politicians allows USA very nuanced analysis of how this relationship is moderated and also under which contextual circumstances attitudes might lose their effect on preferences. Considering the extreme but also quite heterogeneous situation within the EU during the European Economic Crisis, this is not just of interest to better understand preference formation during this period but can also increase our more general understanding of such moderations.

Consequently, while focusing on individual members of the political elite, we address two important research questions. Looking at the issue of representation, we first ask whether the political elite’s preferences for transnational solidarity are driven by similar considerations than those of the citizenry elaborated in previous research. The second question investigates how the relationship between attitudes and preferences is moderated by contextual factors and what this means for the comparative importance of these sets of factors.

Understanding politicians’ preferences for transnational solidarity

Existing studies show that transnational solidarity seems to be higher for politicians compared to voters (Ferrera and Pellegata, Reference Ferrera and Pellegata2019; Basile et al., Reference Basile, Borri, Verzichelli, Cotta and Isernia2020; Basile and Olmastroni, Reference Basile and Olmastroni2020). This points to a problematic gap in terms of political representation – at least, concerning the level of support.

With very few exceptions, however, there is a lack of a comprehensive attempt to identify motives for transnational solidarity within the political elite. Regarding redistribution policies during a period of a high migration numbers, similar relations between sociopolitical attitudes and preferences for transnational solidarity are present for politicians and voters alike (Basile and Olmastroni, Reference Basile and Olmastroni2020). While Basile et al. (Reference Basile, Borri, Verzichelli, Cotta and Isernia2020) work is the only study so far examining political elites’ transnational solidarity and its determinants in times of an economic crisis, e.g., country affiliation, EU attitudes, as well as positioning on globalization and the political left–right spectrum, it also suffers from some weaknesses. First, the numbers of politicians interviewed both per country and per party are rather low, which could explain the lack of significant regression results with regard to context variables. Second, although this study investigates the effect of country affiliation on transnational burden-sharing, it ignores the moderating role of contexts for politicians’ attitudes on their transnational solidarity preferences.

Our work addresses the shortcomings of previous studies and extends them in several respects. Our empirical analyses are based on a sufficiently large database justifying the use of multivariate analysis methods and drawing initial conclusions about hitherto unexplored variances on the political supply side. Moreover, we not only consider the direct effect of country dummies but also examine the moderating role of contextual environments.

Attitudinal base of transnational solidarity

In this paper, we follow Bartels’ (Reference Bartels, MacKuen and Rabinowitz2003) distinction of attitudes – relatively stable psychological leanings – and preferences – particular and situational expressions (see also Kuklinski and Peyton, Reference Kuklinski, Peyton, Klingemann and Dalton2009: 8). This study pursues the idea that attitudes that are more general influence specific preferences (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Bishin and Barr2006). This is related to research on belief systems (e.g., Kuklinski and Peyton, Reference Kuklinski, Peyton, Klingemann and Dalton2009), assuming a certain interrelatedness of attitudes and preferences and to the idea of heuristics (e.g., Kahneman and Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1982), which are used to form preferences while ignoring complexity.

Going back to the seminal work of Converse (Reference Converse2006 [1964]), there is some debate on the comparability of belief systems and processes of attitude formation when looking at citizens and (political) elites. Citizens are assumed to be less consistent than, for example, political elites, who are assumed to think more frequently about politics and are supposed to do so in a more logical way. However, a stronger dependence of preferences on attitudes does not mean that the process differs between the two groups. We would simply expect an even stronger relationship for elites than regular citizens, since elite beliefs are even more strongly structured than mass beliefs (Peffley and Rohrschneider, Reference Peffley, Rohrschneider, Dalton and Klingemann2007). This assumption is not only important for this study or research on representation and representative democracy in general but also for several other fields of research. For example, research on political competition is not only very much based on the idea that there is a common understanding of politics and political issues between parties and voters (e.g., Adams, Reference Adams2012) but has also shown that this is the case empirically (e.g., Lichteblau et al., Reference Lichteblau, Giebler and Wagner2020).

Comparable to support for redistributive policies within a nation state, such as the expansion of the welfare state (see for instance, Amable et al., Reference Amable, Gatti and Schumacher2006; Lefkofridi and Michel, Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017; Kiess and Trenz, Reference Kiess and Trenz2019), preferences for transnational solidarity during the European Economic Crisis should also be based on the politician’s placement on the socioeconomic left–right dimension. The consideration of economic left–right orientations is crucial for studying public conflicts over fiscal transfers (Kleider and Stoeckel, Reference Kleider and Stoeckel2019). In fact, research on public support for transnational solidarity has shown that economically more right-wing citizens tend to be opposed to financial redistribution between countries (Baute et al., Reference Baute, Abts and Meuleman2019), whereas “people on the left were more in favour of increasing the amount of assistance for crisis-affected countries” (Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019: 85). These findings are also supported on behalf of political elites (Basile et al., Reference Basile, Borri, Verzichelli, Cotta and Isernia2020). Therefore, our first research hypothesis reads as follows:

H1: The more socioeconomic left-wing attitudes are held by politicians, the stronger the preferences for transnational solidarity.

By definition, transnational solidarity goes beyond the national context. Hence, attitudes toward international cooperation should be of relevance. In the European context, attitudes toward the EU fit perfectly with this assumption. When European integration policies are generally rejected, willingness to financially invest in the stability of the community or to assist fellow states in crisis should also be low. In the citizenry, Eurosceptic sentiments correlate with feelings of low transnational solidarity (Baute et al., Reference Baute, Abts and Meuleman2019; Reinl, Reference Reinl, Baldassari, Castelli, Truffelli and Vezzani2020), and Eurosceptic parties tend to vote against anticrisis measures (Maatsch, Reference Maatsch2016). In contrast, those citizens who identify with the EU are more likely to favor financial emergency relief (Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019: 88). We therefore also expect to find more support among politicians holding positive attitudes toward the EU and European integration. This assumption was likewise backed by Basile et al.’s (Reference Basile, Borri, Verzichelli, Cotta and Isernia2020) elite study.

H2: The more pro-EU attitudes are held by politicians, the stronger the preferences for transnational solidarity.

Economic difficulties and responsibility ascription: additions to and constraints of the attitude-preference link

Political preferences vary according to people’s social and political environment (Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Kotler-Berkowitz and Swaine1998; Bartels, Reference Bartels, MacKuen and Rabinowitz2003). Zaller (Reference Zaller1992) argues that expressed attitudes strongly depend on the (informational) environment. These insights are in line with Sniderman et al. (Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991) revealing that preferences depend on political predispositions and are context-dependent. As Figure 1 illustrates, in addition to the already discussed effect of general attitudes, we argue that context and environment can both have a direct role for preferences but also a moderating effect (dashed arrow) on the relationship of attitudes on preferences.

Figure 1. Theoretical argument.

Obviously, the number of contextual factors influencing a politician’s preference formation is very high. However, a meaningful selection has to be made. We have decided to follow the same strategy as applied when identifying general attitudes that influence solidarity preferences: again, we draw on research on public opinion. Not only does this allow us to test the general argument of conditionality but also to evaluate whether there are similar mechanisms at work when looking at the political supply- and demand-side.

Kuklinski and Peyton (Reference Kuklinski, Peyton, Klingemann and Dalton2009: 10) claim that people start updating their beliefs if conditions start to change. Changes in the national economic performance constitute such a situation. Individuals living in countries with a good and stable economic performance show more support for intra-EU financial transfers (Kleider and Stoeckel, Reference Kleider and Stoeckel2019; Vasilopoulou and Talving, Reference Vasilopoulou and Talving2020). In contrast, when national financial resources are limited, voters prefer to spend the money on national affairs rather than distributing it within the EU (Lengfeld et al., Reference Lengfeld, Schmidt and Häuberer2015). In simple terms, this kind of transnational solidarity has its price and the willingness to pay this price increases if societies are better off.

However, if we follow the rational choice paradigm, we would instead assume that politicians favor financial redistribution policies if their country benefits as a recipient state. This has already been shown in studies of regional redistribution programs within countries (Heinemann et al. Reference Heinemann, Janeba, Moessinger, Schröder and Streif2014; Balcells et al., Reference Balcells, Fernández-Albertos and Kuo2015) as well as with regard to public support for solidarity actions between EU states. Debtor states are much more in favor of intra-EU financial redistribution policies than creditor states, which usually have to pay (more) for such measures (Genschel and Hemerijck, Reference Genschel and Hemerijck2018; Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019: 89–91). Moreover, the stronger the national economy the less citizens tend to support European economic governance (Kuhn and Stoeckel, Reference Kuhn and Stoeckel2014). All in all, it seems more plausible to expect more support for transnational solidarity if a country’s economic performance is poor or deteriorating.

H3a: The greater the economic misery index in a politician’s home country, the stronger the preferences for transnational solidarity.

Furthermore, despite their more market-oriented political orientation, even right-wing parties from debtor states favored European redistribution policies (Maatsch, Reference Maatsch2014). We therefore assume conditional effects for the national economic performance on the impact of attitudes on transnational solidarity. Depending on the country a politician lives in, s/he may be in favor of financial redistribution policies despite a socioeconomically right-wing or anti-EU position if the economic misery index is high. National economic self-interest outweighs the impact of attitudes and, hence, attitudinal differences should matter less.

H3b: The greater the economic misery index in a politician’s home country, the weaker the effect of attitudes on preferences for transnational solidarity.

Previous research has also shown that whether people are responsible for their current plight constitutes an important criterion for deserving solidarity (van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2000). Whether a politician believes that a country deserves solidarity can be described in our framework as the result of information processing. The outcome of this process influences how general attitudes are transformed into policy preferences, as it constitutes the informational environment (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992; Bartels, Reference Bartels, MacKuen and Rabinowitz2003).

Many citizens living in better off creditor states, such as Germany, have negative preconceptions about their ‘lazy’ fellow EU citizens in Southern Europe (Stjernø, Reference Stjernø2011: 172; Kontochristou, Reference Kontochristou2014). Gerhards and colleagues (Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019: 246) presume that citizens become more skeptical toward intercountry redistribution policies when they get the impression that state administrations in the receiving countries are misusing monetary bailout. Indeed, according to a comparative survey in the context of the European Economic Crisis, one-third of respondents states that no financial aid should be given to countries that have handled money poorly in the past (Lahusen and Grasso, Reference Lahusen, Grasso, Lahusen and Grasso2018: 260–262). In line with this, we expect that politicians tend to be less supportive of transnational solidarity if they believe that the recipient states themselves are responsible for the crisis.

H4a: The greater the ascribed national responsibility, the weaker the preferences for transnational solidarity.

Again, we also expect the impact of attitudes on the willingness to support transnational solidarity to be conditioned by the attribution of responsibility. For example, general attitudes opposed to redistribution or common European strategies should show an especially strong effect of rejecting transnational solidarity if politicians believe that the receiving states are in a self-imposed situation. Identical to H3b, we therefore expect differences in attitudes to matter more or less depending on contextual and environmental factors.

H4b: The greater the ascribed national responsibility, the stronger the effect of attitudes on preferences for transnational solidarity.

Data and operationalization

While there are several data sources and ways to measure policy positions of political parties – ranging from hand- or machine-coded documents to expert judgments – information on individual politicians is rather scarce. This becomes even more problematic when, as in this paper, the researchers are not merely interested in top politicians such as party leaders or presidential candidates, but in a comprehensive coverage of party elites.

We rely on candidate surveys to identify politicians’ policy positions. Specifically, we use data from the Comparative Candidates Survey (CCS, 2020). The political elite data collected on the national level for the module including questions about transnational solidarity is then integrated into a comparative data set covering elections, which took place between 2013 and 2018. Furthermore, the 2014 European Election Candidate Survey (GLES, 2017) provides information for some additional countries and elections, since it uses a more or less identical core questionnaire.Footnote 3 Politicians running for office in the national or European Parliament constitute mid- to high-level political elites who play a major role in shaping the (national) political arena. Hence, understanding processes of preference formation of these actors better and investigating potential differences due to ideology, party, or context can inform future research on party developments or the potential consequences of the personalization of politics.

Our database covers information on politicians from nine EU member states: Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, and the UK. The countries included in this study thus represent a heterogeneous group of EU member states, which differ from each other in many respects, such as national economic performance, the country’s status during the European Economic Crisis (with Greece, Portugal, and Romania as receiving countries), or the duration of EU membership. Moreover, we cover different welfare regimes, different levels of democratic quality, as well as countries with and without a socialist past. In other words, while we are unable to conduct a large-N comparison on the country level, our findings allow for at least some generalization.

As our dependent variable measures transnational solidarity in the context of the European Economic Crisis, we use two survey items for which the respondents’ agreement was measured on a five-point Likert scale: (1) ‘The EU should continue to support all current members of the Eurozone facing major financial crises’ and (2) ‘The EU and/or IMF should provide funds for more investment to stimulate economic growth’. In combination, from a conceptual and a methodological standpoint, these items provide a valid measure of transnational solidarity. We calculate the mean value for each respondent; high values indicate more support for transnational solidarity. Finally, we grand-mean center the values applying post-stratification weights which means that positive values refer to above-average support of transnational solidarity.Footnote 4

As we argued above, specific preferences toward transnational solidarity should depend on general attitudes on two core dimensions of political conflict – socioeconomic issues and EU issues. The surveys provide several items related to these two dimensions. There are three items to measure the socioeconomic dimension: the intervention of the government in the economy, the provision of social security by the government, and the government’s role in reducing income differences (all measured on five-point scales). There are two suitable indicators to measure attitudes on the EU dimension: evaluation of EU membership (three-point scale) and preferences for more or for less European integration (eleven-point scale).Footnote 5 The general attitudes are calculated on the basis of confirmatory factor analyses concerning socioeconomic issues. As there are only two indicators measuring EU issues, we again simply calculate the mean value of the respective items; high values indicate a socioeconomic left-wing or pro-EU position.

We use two items to operationalize ascribed national responsibility for the European Economic Crisis. The first asks about the responsibility of national politicians and governments, while the second refers to all of the people in the country. Combining these items, we cover cultural issues and failures of political elites that were both present in debates during the European Economic Crisis. Again, we calculate the mean values of both items, which are measured on five-point Likert scales; high values represent higher ascribed national responsibility.Footnote 6

As a second constraining factor, we add the economic misery index as a macro-level indicator. Originally introduced as the Economic Discomfort Index in the 1960s and later rebranded as the Economic Misery Index by the Reagan administration (Lovell and Tien, Reference Lovell and Tien2000), the index is calculated as the sum of the unemployment rate and the inflation rate, which we took from Eurostat (2019a, b). Such an index is often used as a proxy for the overall economic situation influencing political attitudes and behavior, e.g., in the context of economic voting (Lewis-Beck, Reference Lewis-Beck2006). To incorporate the lingering effect of economic situations, we use the average value for the period of two to four years before the politicians were surveyed.

We also incorporate several control variables at the micro, meso, and macro level. At the individual level, we differentiate between politicians on the basis of their role and experience by introducing a binary indicator of being a Member of Parliament (MP). We also control for a person’s gender, age (measured in years), and educational attainment (1 = low, 2 = medium, and 3 = high).

Moreover, other factors should also impact the person’s preference regarding transnational solidarity. First and foremost, this preference should be influenced by the party’s position on the two dimensions of political conflict. We measure party positions using data from the MARPOR group (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2018). Building on work by Volkens and Merz (Reference Volkens, Merz, Merkel and Kneip2018), we selected coding categories that best fit the two dimensions of political conflict. Following common practice to transform these frequency scores into positional values for party positions regarding socioeconomic and EU issues, we rely on logit-transformed scales (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011). High values indicate a socioeconomic left-wing or pro-EU position. In addition, whether or not a respondent’s party is in government constitutes another relevant factor to control for. Data to construct this binary indicator (1 = party is in government; 0 = party is not in government) are taken from the GovElec database (WZB, 2019). Government participation is determined at the time when the elite surveys were in the field, which is not always directly after an election has taken place.

On the country level, we add a measure of public opinion regarding transnational solidarity in a country. This helps us to verify whether elite preferences simply cater to voter positions. Here, we use data provided by the 2014 European Election Study (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Popa and Teperoglou2016) and rely on average positions of citizens as it is commonly done in research on party positions or positional shifts (e.g., Adams, Reference Adams2012; Hobolt and de Vries, Reference Hobolt and de Vries2015).Footnote 7 We also control for whether the respondent stood as a candidate at a national or European election. This should allow us to pick up systematic bias due to the election type.Footnote 8

All in all, this allows us to conduct our analysis for candidates of 12 elections in nine different countries. These elections cover more than 50 different political parties and provide data for 3990 politicians.Footnote 9 While the large data requirements result in substantive limitations – e.g., the MARPOR data set only includes parties with parliamentary representation – this nevertheless constitutes the most comprehensive approach to measuring and explaining elites’ positions on transnational solidarity as of now.Footnote 10

We use linear multilevel models to acknowledge the hierarchical and complex data structure with respondents nested in parties nested in elections. The resulting three-level model does not only correct for correlated error terms by cluster, but also provides meaningful standard errors for explanatory variables on the two higher levels. Furthermore, we run the estimation model on weighted data. More precisely, parties are weighted based on their vote share in the last national election, while we also add weights to ensure equal importance for all elections covered. Both decisions help to control for unequal numbers of candidates as well as response rates, which poses a problem in elite surveys, while also considering the political reality in each context. Finally, we have standardized all continuous independent variables following Gelman’s (Reference Gelman2008) approach to standardization, which allows for direct comparison between all variables including categorical indicators.

Results

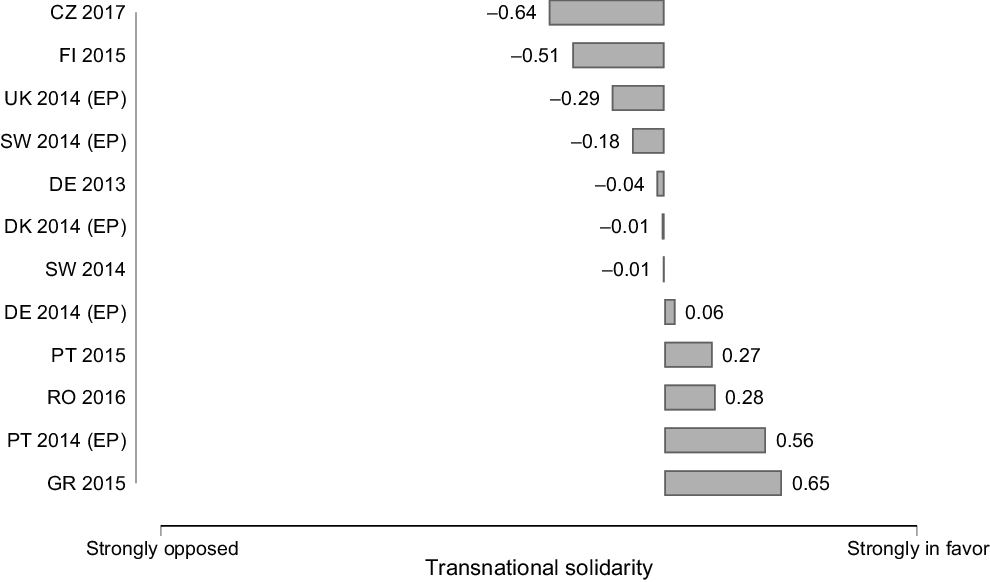

We start the presentation of our empirical results by looking at differences between countries and elections (Figure 2); negative values indicate less support for transnational solidarity than average. Transnational solidarity is seen very positively in Greece, Portugal, or Romania, but not so much in Finland, the UK, and especially the Czech Republic. There seems to be quite some variation between countries and elections, but also a fairly clear pattern: countries that actually benefit from transnational solidarity between EU member states and received financial bailout over the course of the European Economic Crisis are more in favor of such measures. Countries less affected by the European Economic Crisis or which are in general better off in terms of unemployment rates and inflation do not support solidarity that strongly – probably because they would potentially have to pay for adopted solidarity measures. However, countries such as Denmark, Germany, or Sweden would not have benefited directly from such solidarity measures either, but rather occupy an intermediate position. Finally, there does not seem to be a temporal trend in the sense that surveys conducted closer to the high times of the crisis led to less support.

Figure 2. Transnational solidarity by election.

Note: Values represent election means with weights applied. Means have been sorted (from lowest to highest). The scale endpoints refer to the theoretical endpoints of the scale; a value of zero represents the overall mean, as the variable has been grand-mean centered.

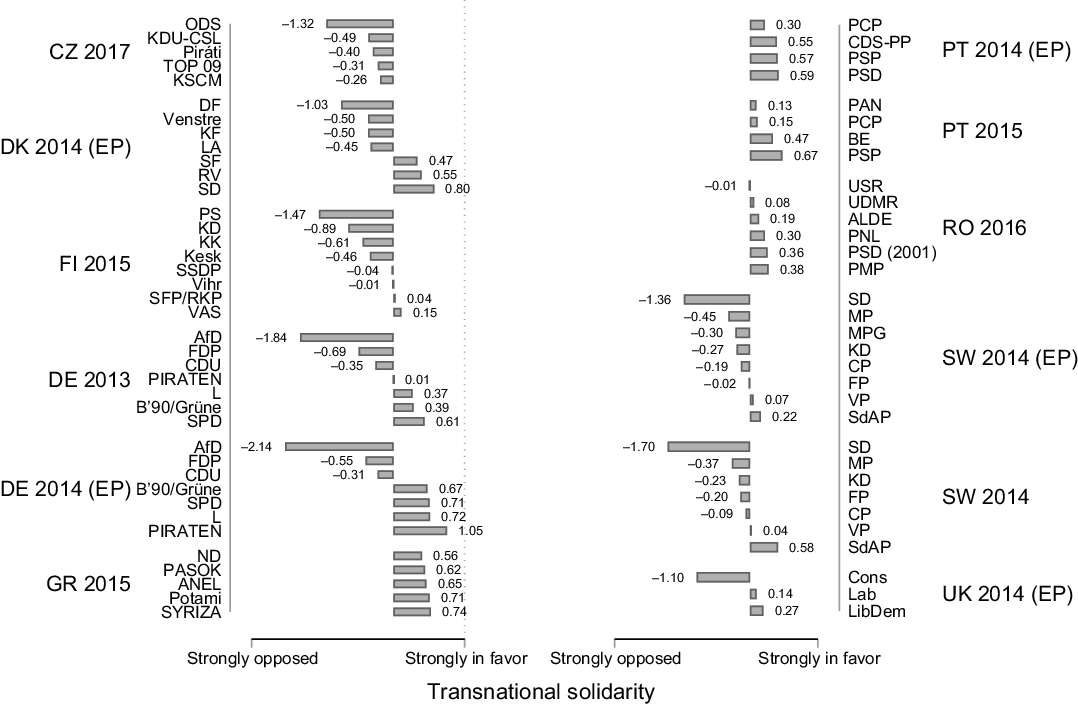

If we look at the differences between parties, we see even more variation (Figure 3). With the exception of Greece and the two Portuguese elections, which show only positive values for all parties, and the Czech Republic with unanimously less than average support, there are positive and negative values in all countries and for all other elections. There seems to be a clear pattern, as parties of party families traditionally associated with more left-wing socioeconomic positions are much more prone to transnational solidarity. For example, looking at the two studies from Germany, we find that candidates of socioeconomically more right-wing parties, in this case, the CDU (including its sister party CSU), FDP, and AfD, reject solidarity measures more strongly than the overall average, while socioeconomic more left-wing parties such as the Left, the Greens, or the SPD show positive values.

Figure 3. Transnational solidarity by party.

Note: Values represent party means with weights applied. Means have been sorted first by country name and then by party means (from lowest to highest). The scale endpoints refer to the theoretical endpoints of the scale; a value of zero represents the overall mean as the variable has been grand-mean centered.

Thinking about the second dimension of general attitudes, there also seems to be a pattern – but somewhat weaker. For all countries, more EU-sceptic parties, such as the various (radical) right-wing populist parties included in our study (for example, the German AfD, the Swedish SD, or the Danish DF), show rather large, negative averages. However, if one considers that skepticism toward the EU is also to be found on the left (Marks et al., Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006), the position of leftist parties’ candidates seems to be mainly driven by their socioeconomic and not their EU issue positions.

All in all, there are substantive differences on the meso and macro levels, and there seem to be certain patterns underlying these differences. In regard to our hypotheses, this provides some indication that politicians from countries facing economic problems are more supportive of transnational solidarity (H3a). At the same time, assuming that socioeconomically more left-wing and more pro-EU parties are represented by electoral candidates with similar attitudes, H1 and H2 could also prove to be valid.

So far, we have only shown that there are differences between countries and parties. On these levels, using different data, other studies cited above have shown variation as well. However, we are primarily interested in micro-level differences in preferences for transnational solidarity. Figure S1 in the supplementary material shows substantial variation on the micro level of politicians’ preferences (sd = 0.91 with a value range of 4). Again, this variation might be driven by country or party differences making a micro-level analysis of political elites irrelevant. Calculating the standard deviation of our measure of transnational solidarity by party results is a very different interpretation, though (see Figure S2). The values range between 0.27 and 1.25 with a vast majority of parties showing standard deviations of 0.6 or higher. In other words, there is a lot of heterogeneity regarding transnational solidarity – even within one and the same party. Hence, assuming that political parties or governments constitute unified actors is not only missing out on a lot of variation when discussing elite preferences but it might in fact even be misleading.

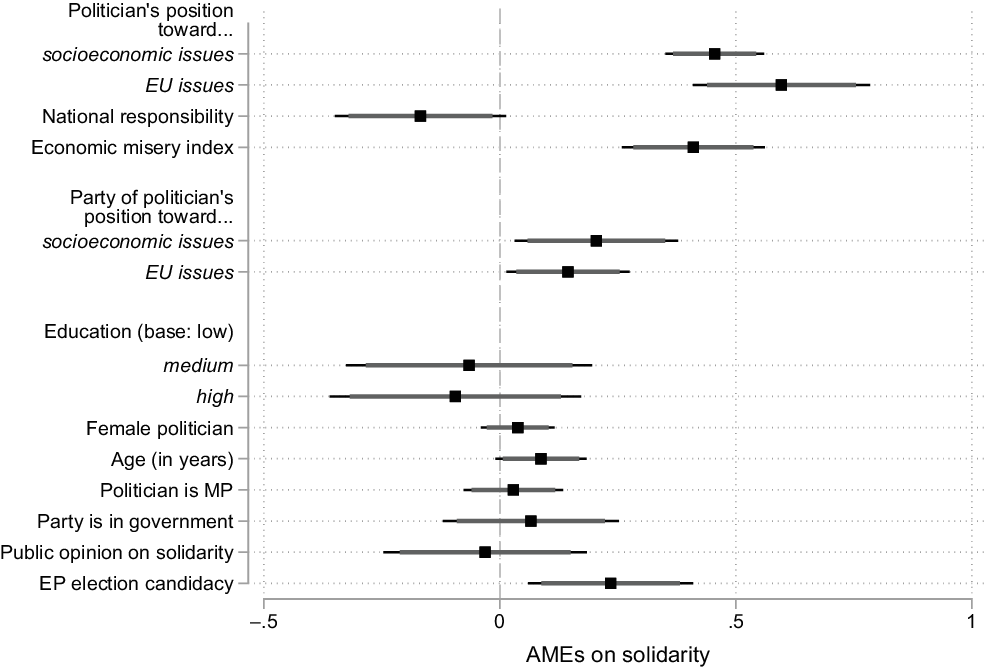

The findings of our multilevel regression model are presented in Figure 4, which depicts the average marginal effects (AMEs) as well as the 90 and 95% confidence intervals. If the confidence intervals do not cross the dashed vertical line, we find a significant effect at the corresponding level. As all continuous independent variables have been standardized, we can compare effect sizes directly.

Figure 4. Marginal effects for predicting transnational solidarity.

Note: Results are based on a multi-level regression model (Table A1 in the appendix).Coefficients represent average marginal effects and 90/95 per cent confidence intervals. Interaction terms are part of the model, but not presented here.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 are both supported: general attitudes determine specific preferences. Socioeconomically more left-wing and more pro-EU politicians do indeed support transnational solidarity significantly strongly. This means that there are similar patterns for citizens and political elites, as these findings are consistent with public opinion studies cited above. If there is a representative gap between political elites and the citizenry, it is not based on differences regarding determinants of preferences for or against transnational solidarity. In comparison to the other independent variables, we also see that the effect is quite substantive for both indicators, but stronger for attitudes toward the EU.

Hypotheses 3a and 4a claim that contextual/environmental effects play a direct role in explaining preferences. As Figure 4 shows, this assumption is partly confirmed. If a politician perceives the receiving country to be responsible for the crisis, preferences for transnational solidarity measures decrease. However, this effect is only significant on the 90% level of confidence. With regard to the economic misery index, we find the expected positive effect, as poor economic conditions in the politician’s home country are linked to being more in favor of solidarity. This effect is also substantially bigger than the effect of ascribed responsibility and constitutes the third largest effect. Comparing the AMEs, preferences seem to be more strongly determined by general attitudes than the contextual/environmental effects. We will, however, turn back to this question when looking at the moderating effects below.

Before moving to these hypothesized indirect effects, we look at our set of controls. We find a significant effect for parties’ positions regarding socioeconomic issues as well as EU issues. Even with all the other variables included, candidates of more left-wing and more pro-EU parties still have significantly stronger preferences for transnational solidarity. This calls for more attention in future studies: It might be that the party context should also be understood as a conditioning factor determining how preferences are formed. It seems obvious that politicians of one and the same party share policy positions and have similar attitudes. Assuming that politicians and party organizations are not driven solely by office-seeking, overall party stances should be a function of these attitudes, and this should result in a substantive correspondence between the positions of a party and the politicians. However, our results suggest that the role of parties is not only to provide a platform for politicians with similar attitudes but to also foster certain preferences. Having said that, the respondents’ attitudes have a much larger effect than party stances which indeed calls for a dynamic perspective on politicians and their party platforms.

Whether the party an electoral candidate is running for is in government or whether the candidacy won a mandate has no impact on transnational solidarity. We also do not find an effect for educational attainment or gender – but there seems to be a slight indication that older politicians are more supportive for financial aid. Politicians’ transnational solidarity is also not driven by public opinion. In contrast, having run for office in an EP election actually increases transnational solidarity, which is quite surprising after controlling for all the other factors. Whether this is due to specific selection criteria for candidates in different political arenas, variation in issue salience or due to entirely different reasons is very difficult to say and goes beyond the focus of this paper. Similar to our findings on party positions, this might constitute a fruitful avenue for future research.

Finally, the model is quite well able to explain variance in preferences for transnational solidarity (see also Table A1). Following the approach by Raudenbush and Bryk (Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002), the overall R2 is 0.48, while the level-specific R²-values vary substantively. On the level of individuals, we explain slightly more than 14% of the variance, while this value increases to more than 95% (party level) and 84% (election level). This clearly indicates that additional factors on the level of individual politicians should be considered in future studies.

To evaluate whether the effects of socioeconomic and EU issue positions are moderated by the economic context and ascription of responsibility (H3b and H4b), we estimate interactions in our multilevel model. All interaction terms are significant with an error probability below (at least) 5% (see Table A1) – which is already a strong argument in favor of confirming our hypotheses. However, graphical representation makes it easier to interpret interactions. Figure 5 presents the predicted values of our dependent variable for different combinations of the attitudinal as well as the potentially moderating factors. All other independent variables are set to their empirical mean.

Figure 5. Transnational solidarity by context and attitudinal camp.

Note: DV:Transnational solidarity. Results are based on a multi-level regression model (Table A1). Estimations represent predicted values with 95 per cent confidence intervals. The solid line refers to an attitudinal value equal to the empiricalmean plus one standard deviation, while the dashed line refers to anattitudinal value equal to the empirical mean minus one standard deviation.

The interpretation of the subplots is straight forward. The plots on the left differentiate between socioeconomically left- and right-wing politicians, while the plots on the right differentiate between politicians with anti- and pro-EU attitudes. Right-wing and anti-EU positions (dashed line) are defined as the mean position minus one standard deviation, and left-wing and pro-EU positions are defined by adding one standard deviation to the mean. Hence, we present predicted values for politicians with different attitudes moderated by the level of ascribed national responsibility (upper plots) and the economic misery index (lower plots).

Unsurprisingly, we find that, overall, economically more right-wing politicians and respondents with less favorable opinions regarding the EU support transnational solidarity to a lesser degree. However, the figure indicates that the relationship of attitudes and preferences is substantially moderated by context and environment. Responsibility ascription seems unimportant for left-wing and pro-EU politicians – they support transnational solidarity regardless, as indicated by the more or less flat line. The picture is very different for politicians with right-wing and anti-EU attitudes as they follow their general attitudes much more closely if they perceive the national actors to be responsible for the crisis. Accordingly, in case a crisis is not attributable to national actors, the willingness to show solidarity is comparatively high, even among right-wing and Eurosceptic politicians. Similarly, if politicians reside in a country facing severe economic problems, differences between respondents with left-wing and right-wing as well as pro- and anti-EU attitudes decrease or even disappear.

Additionally, we can also compare the two attitudes’ effects on the dependent variable at different levels of ascribed responsibility and the economic misery index (Figure 6). Concerning ascribed responsibility, going from the lowest to the highest empirical value changes the average marginal effect – a one-unit change in the independent variable – of socioeconomic attitudes from −0.01 to 0.83 and of EU attitudes from 0.35 to 0.80. Looking at the moderating effect of the economic misery index, going from minimum to maximum, the values for socioeconomic attitudes drop from 0.60 to 0.10 and for EU attitudes from 0.90 to −0.11. Obviously, these differences are very substantial and, taking everything together, we interpret this as a validation of Hypotheses 3b and 4b: the impact of attitudes on preferences is moderated and constrained by contextual/environmental factors.

Figure 6. Conditional effects of attitudes on preferences.

Note: DV:Transnational solidarity. Results are based on a multi-level regression model (Table A1). They represent the average marginal effect of a one unit change with 95 per cent confidence intervals in the respective independent variable on preferences for transnational solidarity.

We also run a couple of robustness checks (see supplementary material, Models 2 to 5 in Table S4 and Figures S3, S4, and S5). As the specified interactions in our main model are quite complex, we also estimated regressions with separate interactions for each context factor and the two attitude measures. Moreover, we also added a dummy variable controlling for being a debtor country or not and tested a differently aggregated measure of ascribed national responsibility which does not rely on the mean of the two items but treats them as sufficient conditions. However, none of these additional models contradicts the interpretation of our main findings.

Discussion

For the EU and its member states, a certain level of transnational solidarity must be standard. Without solidarity it would be impossible to form or to keep alive a stable and institutionalized union of nation states. In fact, solidarity has been at the heart of the European integration process, but it has never been as severely tested as it has been during the last 15 years.

Focusing on the consequences of the European Economic Crisis, this paper investigated drivers of elite opinion regarding transnational solidarity. While there are some studies on public opinion, political parties, or government action, comparative research on political elites in a broader sense is quite scarce. We contribute to the literature by analyzing data of close to 4000 politicians of more than 50 different political parties. In our theoretical argument, we postulate that, in line with public opinion research, general attitudes toward socioeconomic issues and the EU determine preferences for or against transnational solidarity. However, these preferences are also influenced by contextualization. In our empirical model, we test both for a direct effect of economic conditions and the ascription of responsibility, as well as the moderating effects of these factors. We argue that differences in general attitudes are more or less important depending on the contextualization.

Our results show that both left-wing attitudes in terms of socioeconomic issues and more pro-EU attitudes lead to higher levels of transnational solidarity – confirming our first two hypotheses. Furthermore, we find that politicians who ascribe responsibility for the Economic Crisis to national actors or who do not live in a country that also suffers from poor economic conditions oppose transnational solidarity. Finally, it turns out that the latter two factors also have an indirect effect – differences in attitudes do not always lead to differences in preferences. As our hypotheses proclaimed, ascribed responsibility and national economic problems condition the effect of general attitudes mitigating differences between left- and right-wing socioeconomic attitudes as well as pro- and anti-EU attitudes.

This paper makes at least three important contributions to the literature. First of all, we show that elite preferences concerning transnational solidarity are very heterogenous. Even assuming that there is a unified policy position for each party – as done in several earlier studies – seems to be quite misleading. Taking this heterogeneity seriously might help future research to better trace and understand policy shifts as well as internal party conflicts. It might also provide additional motivation for research of the personalization of politics and how mid- to high-level political elites, like electoral candidates, can influence party democracy.

Second, relating our findings to research on public support for transnational solidarity, we conclude that there are very similar patterns in terms of underlying determinants. We interpret this is a positive sign for representative democracy. While elite preferences might be the result of a more coherent belief system or a more rational process, preference formation seems to rely on similar factors. Such similarities between supply- and demand-side are a precondition for meaningful electoral competition, vote choice, and accountability mechanisms. It would be interesting to see whether our findings travel to other contexts calling for transnational solidarity among EU member states – e.g., regarding the distribution of refugees as well as with regard to solidary actions across borders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, the described effects of attitudes on preferences are not static, but vary with context. Considering that, our findings should also be transferable to observations over time; depending on the respective environment, transnational solidarity of politicians should not be stable, but change accordingly. Whether this is actually the case, however, cannot be definitively assessed based on the cross-sectional data presented here, and thus represents a promising direction for future studies.

Although our hypotheses are generally supported, more research is needed in this field in the future. As addressed in the results section, our findings suggest that the embedding of politicians within political parties might also have a moderating effect for attitudes on preferences for transnational solidarity. The same applies to the electoral arena politicians find themselves in. In addition, our empirical models cannot explain parts of the variance at the individual level. Subsequent studies should take these aspects into account and look at them more closely.

Combating the global pandemic and its (economic) consequences confronts the EU probably with its greatest challenge since the end of the Second World War. The knowledge gained from research on transnational solidarity in the wake of the European Economic Crisis can help to better reflect the current concerns, opinions, and behavior of EU citizens and politicians alike. While it seems highly likely that general attitudes and contexts influence preferences for transnational solidarity also regarding the COVID-19 crisis, at the same time, studies might also find relevant differences, as each crisis is obviously unique in some regards. Moreover, preferences and decisions could also be shaped by previous crisis experiences. If people felt misunderstood or treated unfairly during earlier crises, this could reduce their willingness to act in solidarity. However, the EU’s decision to buy vaccine as a unitary actor points to a substantial level of solidarity – at least on the level of governments.

This study focuses only on preferences and not on actual behavior. In other words, we now have a better understanding of the factors that determine elite opinions regarding transnational solidarity. At the same time, however, we do not know whether politicians, and especially elected politicians, also act in accordance with their preferences. There are many potential reasons for such a preference-behavior gap, and future research should investigate whether this gap actually exists regarding transnational solidarity. It seems reasonable to assume that a stronger focus on conditioning factors and, thus, an expansion of the approach presented here could be key.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000138.

Acknowledgments

This paper was possible due to the funding of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for the Solikris Project (Change through Crisis? Solidarity and Desolidarization in Germany and Europe, Grant Number: 01UG1734AX). Additionally, Heiko Giebler's contribution was in part also supported by the Cluster of Excellence “Contestations of the Liberal Script” (EXC 2055, Project-ID: 390715649), funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy.

We would like to thank Ekpenyong Ani for helping us with copy editing and Hanna Doose for preparing the manuscript. We are also grateful for feedback at the 2019 ECPR General Conference as well as the constructive input from the anonymous reviewers as well as the journal editors.

Appendix

Table A1. Multilevel regression results