Introduction

Political science has long been interested in the stability or durability of governments and in their accountability. It has long been thought that if government turnover is too high, then there is too little consistency in government. On the other hand, if governments last forever, that suggests there is little electoral accountability in the governance system. For these reasons, political science has examined the types of institutions that strengthen durability and those that strengthen accountability (Browne et al., Reference Browne, Frendreis and Gleiber1984, Reference Browne, Frendreis and Gleiber1986; King et al., Reference King, Alt, Burns and Laver1990; Alt and King, Reference Alt and King1994; Warwick, Reference Warwick1994; Grofman and Van Roozendaal, Reference Grofman and Van Roozendaal1997; Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1998; Diermeier and Stevenson, Reference Diermeier and Stevenson1999; Laver, Reference Laver2003).

A government, however, is a team of players. A government might be durable by the usual definition, yet have a relatively high turnover of ministers (Laver, Reference Laver2003: 26–27; Huber and Martinez-Gallardo, Reference Huber and Martinez-Gallardo2008: 170–171) or vice versa (e.g., Mershon, Reference Mershon1996; Semenova, Reference Semenova, Dowding and Dumont2015). The literatures on government durability and on ministerial durability tend to be conducted separately and to ask different questions.Footnote 1

The literature on government durability examines what institutional features affect government durability. Here the main institutional factors include the power of the prime minister or, in semi-presidential systems, the president, to dissolve parliament and call new elections; the relative powers of the president vis-à-vis parliament to appoint and dismiss the prime ministers and to appoint or dismiss individual cabinet ministers; and whether or not the president is popularly elected.

The literature on ministerial durability is more concerned with the personal characteristics of ministers – their age, education, gender, and political factors such as whether or not they have been involved in scandals, or how many scandals have involved other cabinet ministers, controlling for factors such as prime ministers, party label, and government popularity (e.g., Berlinski et al., Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2007, Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2012). In other words, when it comes to accountability, the cabinet durability literature concentrates upon collective or governmental accountability, the literature on ministers on individual responsibility. In this article, for the first time, we consider the effects of institutional factors, specifically the power of the president in semi-presidential systems, on both cabinet and ministerial durability. We believe that studying both together will give a more nuanced and rounded view of government durability.

Governments are identified in the literature on government durability by change of prime minister, whether by electoral change or non-electoral replacement; by a new configuration of parties within a coalition government; or by the same prime minister retaining her position after an election. However, while of course prime ministers are foremost in importance in government policy, ministers also have important responsibilities. If some systems have a high turnover of prime ministers, but low turnover of ministers, there might be higher consistency or lower accountability than looking at government durability alone would indicate. While government durability is undoubtedly important, so is ministerial durability, given that ministers generally influence policy in their area of discretion. Analyses usually measure ministers’ durability by their decision to leave the government (either as an individual or by their party leaving government) or by the PM removing them from the cabinet and not through other kinds of exit (such as death or government failure).

Our general question concerns whether institutions that tend to lead to higher government turnover also lead to higher ministerial turnover or whether one compensates for the other. Using a data set composed of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries which share many similar features of political, economic, and societal transformations after the collapse of communism, we examine the relationship between government and ministerial durability under different institutional arrangements. Our central hypothesis, whose derivation we discuss below, is that in semi-presidential systems, stronger presidents will lead to higher government turnover (as usually defined in the semi-presidentialism literature), but lower turnover of ministers.

In the next section, drawing from previous theoretical and empirical findings we draw out a set of eight hypotheses as to how we expect the manner in which presidents are selected and the specific powers they hold in semi-presidential systems will impact upon both cabinet (or government) durability and that of the durability of ministers that compose the cabinets. We then introduce our data and justify our data as pertinent to our research questions. In the subsequent section, we describe the institutional variation across our set of countries and over time (as constitutions are amended). This gives us the variation we require to test our hypotheses. We then defend our methods and the specific manner in which we operationalize our variables. We provide statistical analysis, present and discuss our findings including the robustness of our findings. Our concluding section places our findings within the previous literature.

Previous findings and theory

Governments terminate for many reasons. Theoretically, chief executives have two instruments for curtailing governments: dissolution and new election or a non-electoral cabinet replacement (Lupia and Strøm, Reference Lupia and Strøm1995).Footnote 2 Diermeier and Stevenson (Reference Diermeier and Stevenson1999, Reference Diermeier and Stevenson2000) demonstrate that each risk of government termination has distinct empirical determinants. Many studies address the question of how institutions structure the bargaining game of cabinet terminations (e.g., Baron, Reference Baron1998; Druckman and Thies, Reference Druckman and Thies2002; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Müller, Strøm and Bergman2008; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009; Schleiter and Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016).

Governments can often control the timing and the choice of cabinet termination (Balke, Reference Balke1990; Lupia and Strøm, Reference Lupia and Strøm1995; Smith, Reference Smith2004; Riera, Reference Riera2015). However, calling an early election is dependent upon institutional rules, particularly those determining who has agenda setting and veto power for this choice: parliamentary majority, the prime minister (PM), or the president. In parliamentary systems, there are two instruments for the discretionary termination of cabinets (Lupia and Strøm, Reference Lupia and Strøm1995: 648). The first is the power of parliament to dismiss the PM. The second is the PM’s power to dissolve parliament, which is a counterweight to the parliamentary majority’s dismissal power (Strøm and Swindle, Reference Strøm and Swindle2002: 576). If institutional rules allow PMs to call early elections at their discretion, dissolutions tend to occur more often (Strøm and Swindle, Reference Strøm and Swindle2002: 581–582; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009: 506–507). If dissolution is institutionally restricted, politicians rarely use this instrument. For example, preconditions for calling early elections may include supermajority support, (repeated) government formation failure, or parliamentary gridlock. In addition, many constitutions empower the head of state to confirm parliamentary dissolution after the PM has so proposed. Lupia and Strøm (Reference Lupia and Strøm1995: 654) argue that the existence of this political actor slightly decreases the probability that politicians will attempt to dissolve parliament, which is confirmed by empirical studies (Kysela and Kühn, Reference Kysela and Kühn2007; Becher and Christiansen, Reference Becher and Christiansen2015; Schleiter and Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016). Finally, some constitutions grant presidents the power to unilaterally dissolve parliament. But constitutionally mandated presidential term limits make this less beneficial for presidents than for PMs, who can dissolve parliament and begin a new term in office. Although presidents can use dissolutions to advantage their co-partisans in parliament (Freire and Lobo, Reference Freire and Lobo2006; Kudelia, Reference Kudelia2018; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2018), this strategy can increase the probability of electoral losses at the subsequent presidential election (e.g., Neto and Lobo, Reference Neto and Lobo2009). Cabinet durability, therefore, is expected to be higher if the power of dissolution lies in the hands of the president (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009: 507). Because all constitutions in Eastern Europe restrict parliamentary dissolutions – in other words, none of them gives either PM or president the discretion to dissolve the parliament and call for an early election (Goplerud and Schleiter, Reference Goplerud and Schleiter2016: 435–436) – we do not provide any analysis for early dissolution as such in this article.

Some post-communist countries have opted for semi-presidential systems, in which ‘a popularly elected fixed-term president exists alongside a prime minister and cabinet who are responsible to the legislature’ (Elgie, Reference Elgie and Elgie1999: 13). The existence of a popularly elected president has often been blamed for rendering semi-presidential regimes more prone to policy instability, and even for creating a higher risk of democratic failure (Shugart and Carey, Reference Shugart and Carey1992: 118; Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003: 1084–1085; Moestrup, Reference Moestrup, Elgie and Moestrup2007: 41). However, the common wisdom about dangers posed by popularly elected presidents has been repeatedly challenged by scholars of both semi-presidentialism and cabinet durability. For example, some scholars have considered semi-presidential systems with weak presidents (e.g., in Ireland) to be just a version of a parliamentary system (e.g., Shugart, Reference Shugart1993: 32). Some single-country and comparative studies on cabinet durability have shown that in semi-presidential systems, cabinets are less stable than in parliamentary ones (e.g., Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003), whereas others have failed to identify this negative effect of popularly elected presidents on cabinet terminations (e.g., Somer-Topcu and Williams, Reference Somer-Topcu and Williams2008; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009).

We argue that the mere existence of a popularly elected president has no effect on cabinet and ministerial durability. Compared to their indirectly elected counterparts, popularly elected presidents have a distinct source of legitimacy. Both can experience intra-executive conflicts, usually considered endogenous to semi-presidential systems (e.g., Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003, Reference Protsyk2005; Moestrup Reference Moestrup, Elgie and Moestrup2007). Without any formal cabinet-formation powers, both popularly and indirectly elected presidents have equal chances of seizing political opportunities and trying to force the cabinet to resign or PMs to reshuffle her cabinet (compare, Bucur, Reference Bucur2017). Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1a: Cabinets under popularly elected presidents will be as durable as cabinets under indirectly elected presidents;

Hypothesis 1b: Ministers under popularly elected presidents will be as durable as ministers under indirectly elected presidents.

Semi-presidentialism matters only if the presidents have formal institutional instruments to affect cabinet formation and termination. Two powers are of crucial importance for cabinet durability. The first is the president’s discretionary power to dismiss a cabinet (i.e., to dismiss the PM). The semi-presidentialism literature uses this power extensively as an explanatory variable for cabinet instability in semi-presidential systems (Shugart and Carey, Reference Shugart and Carey1992; Moestrup, Reference Moestrup, Elgie and Moestrup2007). Analysing constitutions adopted or proposed in former communist countries of Eastern Europe, Shugart (Reference Shugart1993: 32) stresses that ‘this institutional design has bred instability wherever it has been used’ (e.g., in Peru before Fujimori, or Germany’s Weimar Republic). Despite its prominence in the semi-presidential literature, this power has been largely overlooked by studies on cabinet durability (with the exception of Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009; and Fernandes and Magalhães, Reference Fernandes and Magalhães2016).

The empirical evidence on the effect of presidential dismissal power on cabinet terminations is mixed. Some argue that it has no influence on cabinet terminations (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009); others, in contrast, suggest that where the president can dissolve cabinets, cabinet durability will be lower than under parliamentarism (Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003: 1084–1085). Others still argue that this power matters only in interaction with the issue of cohabitation (Fernandes and Magalhães, Reference Fernandes and Magalhães2016: 76–77). We suggest that if the president has institutional powers to dismiss cabinet, it will decrease cabinet durability but increase ministerial durability. For presidents, dismissing the PM is a simpler and more effective means to reinvigorate a government than parliamentary dissolution, for which the president might need to negotiate with the PM and/or the parliamentary majority. If presidents can dismiss PMs without changing other ministers (even if incoming PMs may want to move or remove some ministers), this power will increase ministerial durability.

Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2a: The president’s powers to dismiss cabinets will decrease cabinet durability;

Hypothesis 2b: The president’s powers to dismiss cabinets will increase ministerial durability.

The second power is the president’s power to appoint ministers, granted in some semi-presidential countries. While semi-presidentialism treats ministerial appointments as one of the reasons for intra-executive conflict between the president and the PM, and that this can become a source of cabinet instability (e.g., Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2006: 225), this second instrument has been completely ignored in studies of cabinet durability. As with discretionary dismissal power, the president’s power of discretionary appointments allows for active involvement in an area of the PM’s cabinet competence and should therefore be expected to increase conflict between the PM and her ministers. Since one of the bounds of cabinet durability is PM durability, we should expect lower cabinet durability where the president has such power. However, this power will have a positive effect on ministerial durability, because presidents, on average, remain in their positions longer than PMs (see, e.g., Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019) and, therefore, may reappoint ministers to various cabinets. So, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3a: The president’s powers to appoint ministers will decrease cabinet durability;

Hypothesis 3b: The president’s powers to appoint ministers will increase ministerial durability.

Finally, some semi-presidential countries grant their presidents both powers to dismiss cabinets and appoint ministers (e.g., in Ukraine). This might be thought to have the same effect that we see in our Hypotheses 2a,b and 3a,b, that is, cabinet durability will be decreased and ministerial durability increased. However, where the president has both these powers, then the incentives merely to dismiss the prime minister are reduced, for the president can reinvigorate the government by appointing his own new powerful ministers. While prime ministers remain the most important minister, in a sense, the prime minister can be treated by the president as any other powerful minister. We therefore expect that cabinet durability will not differ under such a strong president than it would under a parliamentary government. We do not expect cabinet durability to be decreased under such a strong president. Thus, we expect:

Hypothesis 4a: The president’s power to dismiss cabinets and appoint ministers will increase cabinet durability;

Hypothesis 4b: The president’s power to dismiss cabinets and appoint ministers will increase ministerial durability.

Measuring ministerial durability

Most of the literature on ministerial durability focuses on personal characteristics of ministers or characteristics of the government itself. While some researchers suggest that institutional rules may affect ministerial terminations (Berlinski et al., Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2010: 570; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Dowding and Dumont2012: 516), no one has conducted comparative studies testing these effects. In order to analyse the relationship between cabinet and ministerial durability, we will look at the overall durability of ministers. Furthermore, the literature on ministerial durability tends to be concerned with individual ministerial accountability, and so does not consider overall durability – that is, the durability of ministers across governments (defined as above) – but instead measures the durability of ministers completely independently of government durability. Most duration models looking at ministerial durability censor the ministerial terms by change of prime minister, party coalition, or election.

In this article, we want to see the effects of long-term durability of ministers in relationship to government durability, and whether, despite ministers’ terms often ending as a result of a change in government, ministers in some systems last longer than they do in others. In other words, which ministers survive a change of government. Studies which censor ministers at the end of a government do so because they are interested in the effects of individual ministerial characteristics (gender, education, experience, scandal, etc.) and, to a lesser extent, those of the cabinet (scandals in cabinet, party composition) on ministerial durability outside of governments ending. That is not our concern here. We are examining how differences in institutional rules affect cabinet durability and ministerial durability. As we demonstrate, cabinet durability does not (exclusively) drive ministerial durability. We are not interested in personal characteristics, and only in the institutional effects of different forms of parliamentary and semi-presidential government, so we do not censor. As Fischer et al., (Reference Fischer, Dowding and Dumont2012) argue, whether or not to censor ministerial hazard at the end of a government depends on the specific research question. We are interested in comparing how the institutional rules affect both government durability and overall ministerial durability, and so personal ministerial characteristics are only used as control variables.

Data

Our sample is 14 Central and East European countries, including all of the 11 new EU member states (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia) and 3 post-Soviet countries (Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine). Shortly after the communist regimes in these countries collapsed, all of them joined the Council of Europe (an international organization to uphold the rule of law, democracy, and human rights across the European continent). Based on this time threshold (most joined in the early 1990s, with Russia becoming a member in 1996), we exclude all the other Eastern European (e.g., Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia) and post-Soviet countries (e.g., Georgia) which joined the Council in the late 1990s or 2000s. Albania and North Macedonia were excluded from the analysis because of the lack of data on ministerial durability. Over the observation period, the sample countries have experienced different democratic developments (e.g., authoritarian tendencies in Tuđman’s Croatia or democratic backsliding in Putin’s Russia). We include Croatia (from 1992 until 2000), Russia (from 1991), and Ukraine (from 1994) in the analysis in order to provide comparison with other studies on cabinet stability (Müller-Rommel et al., Reference Müller-Rommel, Fettelschoss and Harfst2004: 871; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009: 498; Conrad and Golder, Reference Conrad and Golder2010: 137; Goplerud and Schleiter, Reference Goplerud and Schleiter2016: 435–436) and ministerial durability in Eastern Europe (Müller-Rommel et al., Reference Müller-Rommel, Fettelschoss and Harfst2004: 877; Semenova, Reference Semenova, Costa Pinto, Cotta and Tavares Almeida2018: 177; Semenova, Reference Semenova2020: 594). In order to control for differences in the level of democracy, we included the variable V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Coppedge, Skaaning and Lindberg2016) into our models of cabinet and ministerial durability; it was insignificant in all models (see the empirical section).

The selected countries provide an interesting variety of institutional rules. Moreover, over the period of observation, half of them adopted legal amendments changing either the mode of presidential election or institutional rules governing cabinet termination and the appointment of ministers. The sample, therefore, also provides valuable within-country variation of institutional rules. Overall, our unique data set includes all ministers (N = 2042) appointed to 195 cabinets in 14 CEE countries. The period of observation for our analyses is from 1990 (or the point at which the first government under a democratic constitution was formed) to 2018.

Variation in institutional rules, cabinet termination and ministerial termination: a descriptive analysis

Table 1 summarizes the instruments by which PMs and presidents may terminate cabinets and ministerial careers. Our sample includes countries with both indirectly (i.e., parliamentary systems) and popularly elected (i.e., semi-presidential systems) presidents, some changing this mode during the period of study. For example, popular presidential elections were introduced in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, but removed in Moldova. In Slovakia, a high degree of party polarization in the late 1990s made it impossible to elect the president from the parliament and the country remained without a president for over a year (Spáč, Reference Spáč and Hloušek2013: 125). After the 1998 elections, the government coalition introduced popular presidential elections via constitutional amendments. In Moldova, in 1999, President Petru Lucinschi initiated a consultative referendum to grant the president the power to dismiss government and tried to force the parliament to either hold a national referendum on the issue or grant him cabinet-dismissal power through constitutional amendments. This backfired, with parliamentary support for the president declining dramatically, and in mid-2000, the parliament removed popular election of the president and decreased his powers (Roper, Reference Roper2008: 120).

Table 1. Institutional rules, cabinet stability, and ministerial terminations in Central and Eastern Europe

a The values were computed by the authors from Doyle and Elgie’s prespow1 scores (Reference Doyle and Elgie2016).

b Ministers appointed to caretaker cabinets were excluded.

Authors’ own classification and calculation.

All the national constitutions in the new democracies specify a constrained dissolution of parliament, which can be initiated under specific circumstances (cabinet-building failures or gridlock) and/or requires presidential consent. The high threshold for initiating parliamentary dissolution makes it rare. As of 2018, several countries, both semi-presidential (Croatia, Lithuania, Romania, and Russia) and parliamentary (Hungary) have never held early elections caused by dissolution of parliament.

Where parliamentary dissolutions occur, it is usually due to failure to form a government or because the government has lost a vote of no confidence – as in Slovenia in 2011. The collapse of a governing coalition has also triggered early elections – for example, in Poland in 2007, when corruption allegations against the leader of a junior partner in the coalition caused its downfall. Intra-party conflicts, too, can be responsible for parliamentary dissolutions – the early Slovenian elections of 2014 took place after the PM, Alenka Bratušek, lost her party leadership position to her predecessor, causing turmoil within the coalition and, eventually, the PM’s resignation and an early election. In general, the constitutions in new democracies pose many institutional obstacles to parliamentary dissolution by requiring agreements between various political actors.

Some constitutions grant their presidents discretionary power to dismiss cabinets. In the late 1990s, President Yeltsin of Russia actively used this power to break down the cabinets of PMs Chernomyrdin, Primakov, and Stepashin (Daniels, Reference Daniels1999; Semenova, Reference Semenova, Dowding and Dumont2015). In Ukraine, from independence to 2006 and again from 2010 to 2014, presidents could dismiss governments. During his first presidential term (1994–1999), President Kuchma dismissed PMs Marchuk and Lazarenko (Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003: 1082). The constitutional amendments of 2004, operating from 2005/2006 to 2010 and again from 2014, deprived the president of this power. The 1990 Croatian constitution granted presidential powers of dismissal, but they had never been used by the time the 2000 constitutional amendments removed them.

The Romanian constitution of 1991 allowed the president to dismiss the PM if the PM is ‘unable to govern’. In 1999, President Constantinescu used this vague rule to dismiss PM Vasile after 10 out of 17 cabinet ministers had resigned. Vasile sat in cabinet without ministers for several days before eventually resigning (Gherghina, Reference Gherghina and Hloušek2013: 265). The 2003 amendments to the constitution explicitly denied the president discretion to dismiss the PM, thus confirming the validity of the previous used power of dismissal.

Finally, some constitutions grant the president the power to appoint ministers. The Ukrainian constitution allows the president to appoint ministers in foreign affairs and defence. In Russia, presidential power to appoint ministers is granted by the federal law on government. From 1992 to 1997, the president could appoint ministers of foreign affairs, the interior, defence, and national security. Since 1997, he can also appoint ministers of justice and emergency situations (Semenova, Reference Semenova, Dowding and Dumont2015). In Poland, until the constitutional amendment of 1997, the popularly elected president shared control with the PM over the nomination of ministers of defence, foreign affairs, and the interior.

Table 1 also reports the average duration of cabinets and ministerial careers. Two important patterns emerge from the descriptive analysis. First, the average cabinet duration is shorter than the average ministerial duration in post-communist countries. Second, the average cabinet duration is slightly longer for popularly elected than for indirectly elected presidents. We now turn to the challenge of explaining how specific institutional rules described in constitutions and legal texts affect cabinet durability and ministerial terminations.

Methodology and the operationalization of variables

We are interested in the effect of institutional rules on both cabinet and ministerial durability, so we perform two analyses. In the analysis of cabinet durability, our dependent variable is the Survival Time of a Government (in months).Footnote 3 Because we are interested in exploring the determinants that affect the risk of early elections and non-electoral replacements separately, we used a competing risks approach (Diermeier and Stevenson, Reference Diermeier and Stevenson1999). We first coded the type of failure (early dissolution and non-electoral replacement) each cabinet faced. Cabinet dissolution is defined as a situation in which the PM and/or the president chooses to call early elections; it distinguishes early elections from constitutionally necessary early elections (e.g., after major constitutional amendments) and from regular elections, which occur when a parliamentary term expires. In some semi-presidential systems, cabinets are replaced at the end of the presidential term. Non-electoral replacements of cabinets define cabinet terminations because of a change of governing coalition or PM which is not the result of elections. Second, we calculate two models, one for each type of risk, in which cabinet failure because of the other risk is censored (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones, Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones2004: 168–169). For studying ministerial durability, our dependent variable is the Status and the Survival Time of a Minister (in months). We measure ministerial tenure for each minister in all cabinets and all portfolios to which this minister was appointed.

In both analyses, our major explanatory variables are the termination and appointment powers of the PM and president. Specifically, the effects of the following institutional powers on ministerial and cabinet durability will be assessed: (1) the mode of presidential elections, which defines the type of a political system (a semi-presidential and parliamentary one); (2) the president’s power to dismiss cabinets; (3) the president’s power to appoint ministers, and (4) the president’s combined power to dismiss cabinets and appoint ministers. All these variables are coded from each country’s constitutional and legal texts (1 if the institutional rule is present and 0 otherwise), in effect since 1990 (or the year of the country’s first democratic election).

Finally, we use a set of control variables in each analysis. The control variables for cabinet durability include cabinet- and parliament-specific factors (Strøm and Swindle, Reference Strøm and Swindle2002; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Müller, Strøm and Bergman2008; Somer-Topcu and Williams, Reference Somer-Topcu and Williams2008; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009; Conrad and Golder, Reference Conrad and Golder2010; Nikolenyi, Reference Nikolenyi2014). The features of a specific cabinet strongly influence the value that it has for political actors in the political system (Warwick, Reference Warwick1994). Specifically, the variable Coalition (1 if a cabinet is a coalition) is included; we expect that the existence of a coalition will restrict opportunistic dissolutions and so coalition cabinets should be more durable than single-party ones (Strøm and Swindle, Reference Strøm and Swindle2002: 582). In contrast, Minority cabinets (1 if a cabinet is a minority cabinet) are expected to be less durable because of their limited ability ‘to generate effective public policy’ (Strøm and Swindle, Reference Strøm and Swindle2002: 548), as too are Caretaker cabinets (Warwick, Reference Warwick1994; 1 if a cabinet is a caretaker cabinet).

To account for the high occurrence of technocratic cabinets in post-communist countries (Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2005), we include the variable PM’s party in government (1 if the cabinet includes the PM’s party). We expect the cabinet presence of the PM’s party to increase the policy and office value for PMs, thus decreasing the risk of cabinet failure. The variable Maximum Duration of the Cabinet (in years) measures the period until the constitutional election term at the time of cabinet formation. The benefits for the chief executive in continuing the current government decline as a regular election approaches (Balke, Reference Balke1990: 202–203; Lupia and Strøm, Reference Lupia and Strøm1995: 656; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009: 507). Cabinet fractionalization measures the number of coalition partners, to control for the complexity of bargaining among coalition partners over cabinet terminations (Warwick, Reference Warwick1994; Druckman, Reference Druckman1996). We expect greater cabinet fractionalization to decrease cabinet durability. Similarly, Parliamentary fractionalization is expected to decrease cabinet durability (King et al., Reference King, Alt, Burns and Laver1990: 858, 863; Laver and Schofield, Reference Laver and Schofield1990: 161). The fragmentation of parliaments is measured by the effective number of parties in parliament (Laakso and Taagepera, Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979). Finally, in order to control for the effect of democratization on cabinet stability, we include the variable V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Coppedge, Skaaning and Lindberg2016), which measures the ‘institutional guarantees’ laid out in Dahl’s (Reference Dahl1973) concept of ‘polyarchy’. The data refer to the level of electoral democracy at the time of cabinet formation. We expect higher cabinet durability in countries with a higher level of electoral democracy.

Our analysis of ministerial durability uses as control variables cabinet- and parliamentary-specific determinants which have been shown to affect the PM’s ability to deal with adverse selection and moral hazard delegation problems. Specifically, coalitions decrease the ability of PMs to dismiss adversely selected ministers, because coalition agreements often prevent personnel changes without renegotiation of the coalition agreement (Indridason and Kam, Reference Indridason and Kam2008). On the other hand, ministers from the PM’s party have a higher risk of dismissal, since losing them does not endanger the survival of government (Huber and Martinez-Gallardo, Reference Huber and Martinez-Gallardo2008: 172–173). Thus, we include Coalition and PM’s Party (1 for serving in a coalition government and for belonging to the PM’s party).

We also add two variables describing the type of the cabinet: Majority (1 in a majority government) and Minority (1 in a minority government). The reference category for these variables will be Non-parliamentary cabinets (i.e., those whose formation is not dependent on parliamentary elections) that have been formed in Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine. In order to decrease the likelihood of delegation problems, the PMs (and political parties) must screen potential candidates for cabinet positions (Berlinski et al., Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2007, Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2012; Bucur, Reference Bucur2017). The probability of adverse selection should be lower in majority than in minority cabinets, because the former have a larger pool of candidates to select from (see Huber and Martinez-Gallardo, Reference Huber and Martinez-Gallardo2008: 177). We therefore expect that ministerial terminations will occur more often in minority than in majority cabinets.

We also include a set of individual-level control variables in our analysis of ministerial durability. Two variables indicate whether a minister had held Foreign Affairs or Defence portfolios (1 if appointed to either). We selected these two portfolios because, in virtually all constitutions of post-communist countries, they fall within the presidential areas of influence because presidents are the commanders-in-chief of military forces. They also appoint ambassadors and formulate foreign policy goals. We therefore expect ministers in these portfolios to have lower termination rates because of their strong connections to the president.

Salient portfolios afford incumbents longer tenures than less salient portfolios (Berlinski et al., Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2007, Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2012; Quiroz Flores, Reference Quiroz Flores2017), because they are highly prestigious and desirable, so potential candidates are carefully screened, which decreases adverse selection (Huber and Martinez-Gallardo, Reference Huber and Martinez-Gallardo2008: 172). To capture this, we include the variable Portfolio of finance (1 if appointed to this portfolio), which is ranked as one of the most prestigious portfolios in both Western and Eastern Europe (Druckman and Warwick, Reference Druckman and Warwick2005: 30; Druckman and Roberts, Reference Druckman and Roberts2008: 114).

The variable Parliamentary/party experience measures the effect of the minister’s political experience on termination risk.Footnote 4 We expect the choice of ministers from parliaments and party offices decreases the risk of adverse selection; they should therefore have lower chances of being dismissed than ministers recruited from outside politics (Blondel and Thiebault, Reference Blondel and Thiebault1991; Semenova, Reference Semenova, Costa Pinto, Cotta and Tavares Almeida2018). Finally, we include Age of the minister at the time of appointment and Gender (1 if a minister is a woman).Footnote 5

A number of methodological considerations guide our model selection. Because we want to examine the effects of institutional rules and a set of control variables on cabinet and ministerial survival, we use survival analysis. As we have no specific assumptions about the underlying distribution of hazard function, we choose a semiparametric Cox proportional hazard model (Cox, Reference Cox1972). Mathematically, the survival model estimates the baseline hazard function ho(t) as well as the estimates of β and its variance–covariance matrix: h(t) = h0(t) exp(β 1χ1 + … + β kχk). The outcomes of a survival model are measured as the hazard ratios: that is, the probability that an individual minister will exit a cabinet at time t provided the minister survives until this point (for the case of cabinets, that an individual cabinet will be terminated provided it survives until the time t).

We assume there are unobserved country-specific risks endangering cabinets and ministerial careers, so we estimate Cox proportional hazard models with country-level shared frailty (random effects) in order to provide some control. We assume that all ministers in a country share the same frailty, but frailty might differ between countries. These models are similar to multi-level models with lower-level units nested into higher-level ones (countries). The frailty term in these models is assumed to have a gamma distribution, with mean 1 and variance θ (theta). In each model, we control for these random effects (theta). In each case, theta was highly significant at P < 0.001.

Institutional rules and the analysis of cabinet durability in post-communist countries

In Table 2, we report coefficients from the Cox proportional hazard model. Coefficients above 1 mean that the determinant increases; below 1 the variable decreases the hazards of cabinet termination. By convention, cabinets that are terminated because elections are censored (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Dowding and Dumont2012). Since only 22 out of 195 post-communist cabinet terminations result from early elections (see also Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009: 498) we could not estimate a separate model for these cases of cabinet terminations. We therefore estimate the survival of governments formed without there being new elections.

Table 2. Cabinet durability between elections (non-electoral cabinet replacements)

* P < 0.10, **P <0 .05, ***P <0 .01.

Based on robust standard errors clustered by country.

Authors’ own calculations.

We see from Table 2 that having popularly elected presidents makes no difference to cabinet durability, in line with our Hypothesis 1a, though contradicting a widely accepted assumption about semi-presidentialism (Model 1c). The ability of the president to dissolve the cabinet at their discretion (by dismissing the PM) between elections also has no effect on cabinet durability, contradicting our Hypothesis 2a drawn from semi-presidentialism research (Model 1c). The power of the president to appoint ministers decreases cabinet durability when we include an interaction between this presidential power and the president’s power to dismiss cabinets and do not control for various other factors, such as coalition governments and how democratic the system is (Model 1b). This suggests that our Hypothesis 3a is overwhelmed by other considerations, such as partisan considerations of coalition building, and other institutional effects such as the maximum duration between mandated elections. The individual effect of the president’s power to appoint ministers remains negative but it is marginally significant (Model 1c). Our Hypothesis 4a is confirmed. The discretionary power of presidents both to dissolve cabinets by dismissing the PM and to appoint ministers increases cabinet durability (Models 1a and 1b; Figure 1).

The effects of control variables on cabinet durability largely support expectations drawn from previous studies (Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Müller, Strøm and Bergman2008; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009). Specifically, the risk of non-electoral replacements is significantly higher for caretaker cabinets and if parliamentary fractionalization is high. Other control variables are not statistically significant but generally show the expected tendency of the effects. For example, the maximum duration of the cabinet term does not affect cabinet durability between elections, and minority governments have higher termination hazards.

Institutional rules and ministerial durability

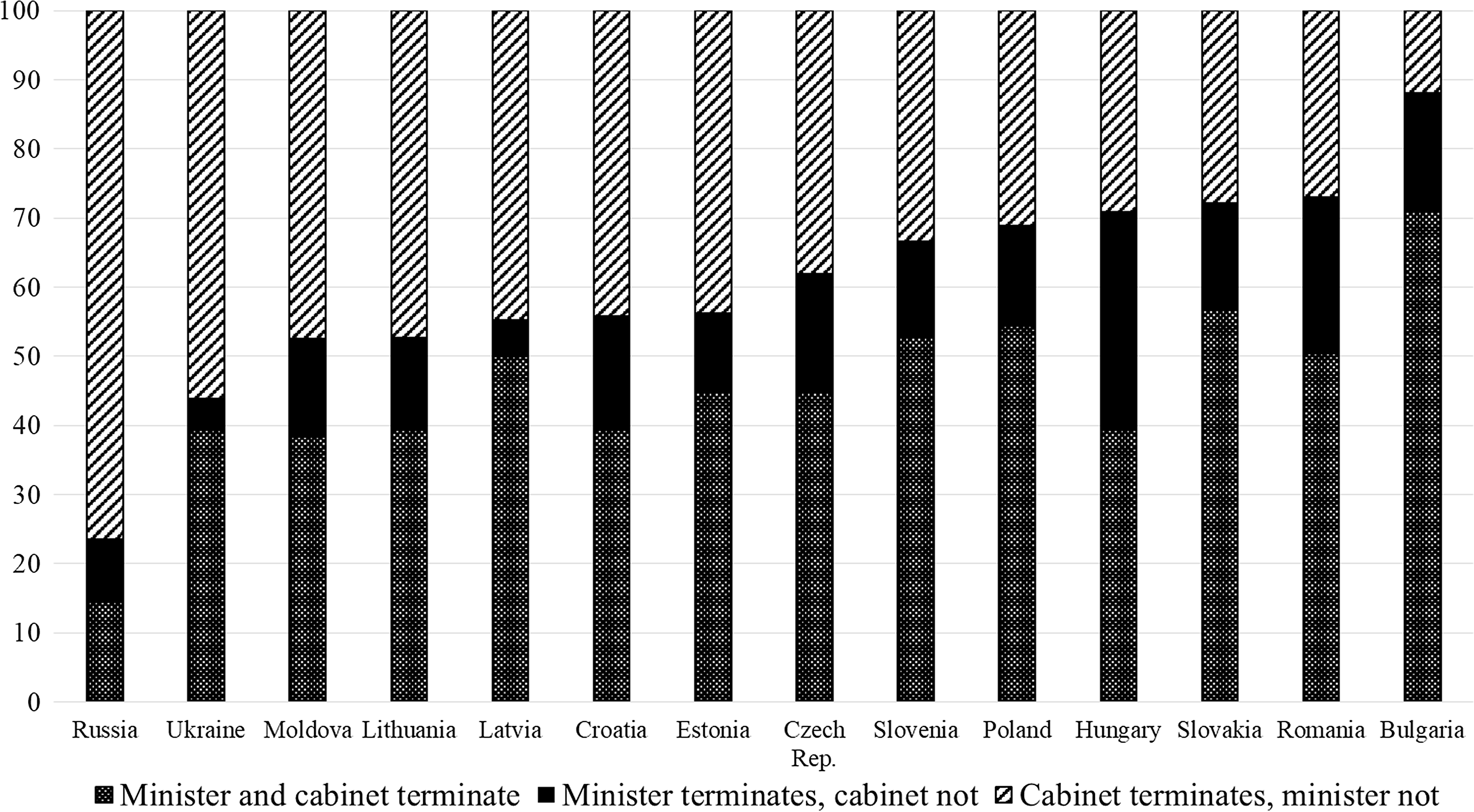

We now turn to the more difficult issue of measuring ministerial durability in relation to cabinet durability. The entry and exit dates for each minister in the 14 countries have been coded,Footnote 6 and each minister assigned to one of three categories: ministers (1) reappointed to subsequent cabinet when their initial cabinet fails (upper bar, ‘Cabinet terminates, minister not’); (2) exit during their first cabinet (middle bar, ‘Minister terminates, cabinet not’); and (3) terminated when the initial cabinet fails (lower bar, ‘Minister and cabinet terminate’). Ministers who had not left the cabinet by the end of the observation period were censured, since their duration is unknown.

We see that at least half of all ministers in six countries failed in their first (and only) cabinet (Figure 2, lower bar). This pattern is particularly strong in Bulgaria, Poland, and Slovakia. In contrast, in former Soviet countries (e.g., Lithuania and Moldova), ministers are often reappointed to various cabinets, sometimes under various PMs (Figure 2, upper bar). The duration of ministerial careers in Croatia, the Czech Republic, Latvia, and Estonia is more variable, as shown by the similar numbers of ministers exiting with their first cabinet and those reappointed. The careers of approximately 15% of ministers terminate between government formation and its end (Figure 2, middle bar). The inter-country variation in the number of ministers failing during one cabinet ranges from 5% (Latvia and Ukraine) to approximately 32% (Hungary). These aggregate findings suggest that, in half the countries, when the government fails, its ministers often remain in office and continue to serve under the new PM.

Figure 1. Non-electoral cabinet replacements. Adjusted predictions of the president’s power to discretionally dismiss cabinets and to appoint ministers (with 95% CIs). Based on Model 1b (control variables are set at means). Author’s own calculations.

Figure 2. Ministerial terminations in Central and Eastern Europe (as a percentage of all appointed ministers). Categories are mutually exclusive; ministers appointed to caretaker cabinets and ministers who were still in cabinets by the end of the observation period were excluded from the analysis. Authors’ classification and calculation.

The results of the shared frailty Cox survival model of ministerial durability are displayed as hazard ratios (Table 3).Footnote 7 A hazard ratio above 1 means an increase in the risk of failure; a hazard ratio below 1 means a decrease.

Table 3. Determinants of ministerial terminations in Central and Eastern European countries

* P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, †P < 0.10.

a The reference category consists of non-parliamentary cabinets and minority cabinets.

b The reference category consists of non-parliamentary cabinets and majority cabinets.

Hazard ratios with standard errors (in parentheses) are reported. Standard errors of hazard ratios are conditional on theta

Authors’ own calculations.

Our Hypothesis 1b is confirmed, as there is no difference between popularly elected and indirectly elected presidents with regard to ministerial durability (Model 2c). Being popularly elected seems to bring no extra authority beyond the de jure powers of presidents. The president’s discretionary power to dismiss cabinets (by dismissing the PM) increases ministerial durability, confirming our Hypothesis 2b (Model 2c). The president’s discretionary power to appoint ministers also increases ministerial durability, confirming our Hypothesis 3b (Model 2c). The sign for ministerial durability where presidents have the combined power to dissolve cabinets (by dismissing the prime minister) and appoint ministers is also in the direction of increasing ministerial durability (Models 2a and 2b), as in our Hypothesis 4b; however, it does not reach normal considerations of statistical significance (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Ministerial durability. Adjusted predictions of the president’s power to discretionally dismiss cabinets and to appoint ministers (with 95% CIs). Based on Model 2b (control variables are set at means). Author’s own calculations.

The effects of our control variables largely confirm previous findings. For example, ministers in coalitions tend to survive longer than their counterparts in other types of cabinets, while high parliamentary fractionalization tends to reduce ministerial durability. Neither majority nor minority cabinets have any significant effect on ministerial durability. Against expectations, the risk of being terminated is not higher for ministers from the PM’s party than for ministers from other parties. This effect may stem from a massive recruitment of politically inexperienced ministers in post-communist cabinets, who suffer higher risks of being dismissed than their partisan counterparts (e.g., Semenova, Reference Semenova, Costa Pinto, Cotta and Tavares Almeida2018: 190–192).

At the individual level, the minister of foreign affairs is more durable than other ministers, but holding the defence or finance portfolio does not increase ministerial durability. As in Western European parliamentary countries, gaining political experience (as an MP and/or a party leader) increases the chances of staying in government. Finally, there are no effects of the major socio-demographic control variables (age and gender) on ministerial termination in post-communist countries.

Discussion

We demonstrate that the powers of the president are essential determinants of cabinet and ministerial durability. While the effects of some major constitutional rules on cabinet durability are well known (Strøm and Swindle, Reference Strøm and Swindle2002; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009; Fernandes and Magalhães, Reference Fernandes and Magalhães2016) we show that presidential powers also have substantial effects on ministerial durability. Our dual analytical perspective demonstrates that these rules have profoundly different effects on cabinet and ministerial durability summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of hypotheses on cabinet and ministerial durability

In our data, semi-presidential cabinets are not less durable than in parliamentary systems (see also Somer-Topcu and Williams, Reference Somer-Topcu and Williams2008; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009: 505–506). Although some semi-presidential cabinets in post-communist countries were indeed unstable during the early 1990s (Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003, Reference Protsyk2006; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009: 505), they have been fairly durable subsequently. This durability, however, does not depend on the level of electoral democracy in post-communist countries (Table 2), but on other factors: for example, the consolidation of party systems and stabilization of the political landscape.

Similarly, we find that semi-presidentialism (the existence of a popularly elected president) alone has no effect on ministerial durability. Researchers on post-communist countries have provided many examples of the destabilizing effects of popularly elected presidents on ministerial durability. For example, in the cohabitation period from 1993 until 1995, Polish President Lech Wałęsa refused to nominate some ministers appointed by the prime ministers (Sula et al., Reference Sula, Szumigalska and Hloušek2013: 114). In 2012, Lithuanian President Grybauskaitė refused to appoint two ministers from PM Butkevičius’ party (Krupavičius, Reference Krupavičius and Hloušek2013: 226). Presidents may also withdraw their support for individual cabinet ministers, which may cause ministerial dismissals and even lead to cabinet breakdown. For example, Lithuanian President Adamkus declared that he had lost his confidence in two ministers nominated by the Labor Party and asked PM Brazauskas to reshuffle his cabinet. Eventually, Brazauskas’ cabinet resigned and Kirkilas formed a new cabinet. However, indirectly elected presidents can also influence cabinet formation by refusing or delaying appointments of ministers (e.g., Tavits, Reference Tavits2009: 62–63). Thus, the mode of presidential elections alone is a negligible factor in ministerial durability. What is more important are the individual and combined cabinet-formation powers granted to the president by the constitution and legal rules of the country.

Extensive non-legislative presidential powers affect cabinet and ministerial durability differently. The presidential power to dismiss cabinets, for example, does not increase the risk of non-electoral cabinet replacements. One of the reasons may be that, in practice, presidents are restricted, because their new candidate for the prime ministership will need to be accepted by the parliament (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009: 507). It is indeed the case that virtually all constitutions in new democracies require parliamentary consent to a PM proposed by the president. This finding contradicts, however, the assumptions widespread in studies on semi-presidentialism (Shugart, Reference Shugart1993; Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003, Reference Protsyk2006). Many of these studies use the Russian and Ukrainian examples of presidential involvement in cabinet terminations in the 1990s and link cabinet instability in these countries with the presidential power to dismiss cabinets. They overlook, however, the fact that since the 2000s, in both countries, cabinets have been more stable than in the 1990s (e.g., Semenova, Reference Semenova, Dowding and Dumont2015).

Presidential powers to discretionarily dissolve cabinets strongly increase ministerial durability. This finding again contradicts assumptions derived from semi-presidentialism studies, which suggest that the risk of ministerial terminations in these systems will be higher as ministers may be dismissed by the PM, and they may suffer a collective dismissal if the president discretionarily terminates the cabinet (e.g., Protsyk, Reference Protsyk2003, Reference Protsyk2005, Reference Protsyk2006). We argue that where presidents can terminate cabinets, PMs will aim to decrease conflict by selecting ministers acceptable to both parliament and the president. For example, in 2008, President Medvedev appointed Dmitry Patrushev to the portfolio of agriculture. While Patrushev was qualified (he had headed the Agricultural Bank of Russia), his appointment was more to placate Putin; he is the son of Nikolai Patrushev, Putin’s long-term ally, fired by Medvedev because of personal conflicts (Nazarets, Reference Nazarets2008). In Ukraine, in 1995, PM Marchuk reappointed Roman Shpek as minister of the economy. Shpek had held this portfolio under the former Communist PM Masol and had been confirmed in his position by previous President Kravchuk. Kuchma nevertheless considered him as an ally in initiatives to reinvigorate the economy (Åslund, Reference Åslund2009: 68–69).

As shown above, presidents rarely use their power to summarily dismiss cabinets; the risk of collective dismissal for ministers is therefore moderate. Country-based studies reveal that presidents may also use their dismissal power in order to signal change, as PMs do with cabinet reshuffles. Unlike PMs, the president may use this power to reinvigorate a government by removing the PM without much changing the cabinet. For example, Yeltsin fired PM Kirienko (1998) in favour of Yevgeny Primakov (1998–99), who successfully mitigated negative consequences of the national financial crisis of 1998 (Daniels, Reference Daniels1999: 32). In Primakov’s cabinet, half the ministers had served under Kirienko (Semenova, Reference Semenova, Dowding and Dumont2015). While presidents in semi-presidential systems may informally control the PM through their decision to dismiss ministers (see Hloušek, Reference Hloušek2013), those with formal powers to do so (through their cabinet dismissal power) exercise a stronger restrictive effect on the PM’s use of dismissal power, which positively influences ministerial durability.

Presidential powers to appoint ministers have a negative but marginal effect on cabinet durability and a strongly positive one on ministerial durability. Theoretically, this power complicates the bargaining game over ministerial terminations between the president and the PM. The president, however, is a dominant actor in this game because, through ministerial appointments, he ensures the realization of his preferences in highly salient policy areas and is able to re-nominate his appointee to the next cabinet. For the PM, the presidential power to appoint ministers manifests adverse selection and moral hazard problems, which cannot be effectively solved by the PM within the given institutional environment. The president may nominate ministers whom the PM considers either unsuitable or disloyal, but the PM cannot dismiss them without presidential consent. This institutional arrangement is also strongly associated with ministerial drift, because, when accepting presidential appointees, the PM loses a certain amount of policy control over highly prestigious portfolios. As with adverse selection, the ministerial drift of presidential appointees can be punished by the PM only with presidential consent.

In this institutional environment, presidents and PMs have different coping strategies for these delegation problems. In the case of conflicts with presidential appointees, the PM must accept the status quo, persuade the president to appoint another minister or resign.

A president in conflict with the PM has two strategies. The first is to keep the appointee, thereby forcing the PM to resign. Because the nomination of a new PM will need parliamentary consent, this strategy may be costly for the president in the long term. The second strategy is to nominate another appointee, taking into account the PM’s preferences. The president may appoint a minister from the PM’s party or a non-partisan, thereby decreasing the probability of ideological conflict between the PM and the presidential appointee.Footnote 8 As a result, there is a high degree of ministerial continuity in such an institutional environment.

Finally, we also tested for an interactive effect of presidential powers both to dismiss cabinets and to appoint ministers (as in the Russian and Ukrainian legal frameworks). Our results suggest that a combination of both powers has a significantly positive effect on cabinet durability. It supports previous findings on both countries that the presidents do not use their cabinet dismissal power often (Daniels, Reference Daniels1999). In contrast, both powers are not needed to be present for a positive effect on ministerial durability. This confirms our assumptions that powerful presidents as dominant actors in the political system have more opportunities to formally and informally influence the ministerial selection, thereby reducing the risk of conflicts over ministerial terminations.

Robustness

The robustness of our models was tested in several ways. First, we included the square of the risk score as a regressor in the model (link test) in order to test for nonlinearity in the specification of the determinants. Second, we conducted global tests of the proportional hazards assumption on which the Cox model is based, using Schoenfeld residuals. The results of both tests are reported at the bottom of Tables 2 and 3. None of them gives reason to reject any of the models.

Third, we examined the robustness of our main findings from the analysis on non-electoral cabinet replacements by estimating cabinet durability as a pooled phenomenon, with only cabinets terminated because of regular elections being censored (for details, see Supplementary Materials, Table 5). By running a reduced model (compare Table 2, Model Ib), the likelihood of cabinet failure is significantly lower if the president has powers to discretionarily dismiss the cabinet and appoint ministers (exp(B) = 0.28, P < 0.000).

Fourth, we estimated our models using a different specification of our explanatory variables. One specification is the type of semi-presidentialism proposed by Shugart and Carey (Reference Shugart and Carey1992). They distinguish between premier-presidential and president-parliamentary systems; in the former, popularly elected presidents are empowered to nominate the PM for parliamentary confirmation, but cannot dismiss the cabinet discretionarily, while in the latter, cabinets can be dismissed by either the parliament or the president. We used these sub-types and estimate their effects on non-electoral cabinet replacements (for details, see Supplementary Materials, Table 6). The results show that in president-parliamentary systems, non-electoral replacements of cabinets occurred significantly less often than in parliamentary systems (exp(B) = 0.22, P < 0.000).

Another specification of the explanatory variables we used was Doyle and Elgie’s Presidential Power Index (Reference Doyle and Elgie2016). We used normalized scores of prespow1 Index for measuring the general effect of presidential power (both its legislative and non-legislative components) on the cabinet and ministerial terminations (for details, see Supplementary Materials, Tables 7 and 8). Confirming our results, the strength of presidential power (which strongly correlates with the presidential competences of discretionary cabinet dismissal and ministerial appointments) is negatively related to the likelihood of non-electoral replacements of cabinets (exp(B) = 0.12, P < 0.05). The effect size of this measure (which combines both executive and non-executive competences of the president) is even more substantial compared to the effects of individual institutional rules examined in the article. We also calculated the Cox regression model of ministerial durability using the Presidential Power Index (Doyle and Elgie, Reference Doyle and Elgie2016). Again, our findings were confirmed; post-communist ministers remain in their positions longer under strong presidents (exp(B) = 0.21, P < 0.001).

Finally, we estimated the models on cabinet and ministerial durability by excluding Russia and Ukraine from the sample because some scholars argue that both countries are characterized by an extremely strong presidency (e.g., Shugart and Carey, Reference Shugart and Carey1992), which may affect our results.Footnote 9 For additional regressions, we excluded the president’s power to appoint ministers and the interaction between this power and the president’s power to dismiss cabinets because no country in our reduced sample has applied such institutional rules. The results have confirmed our findings: The existence of a popularly elected president does not have any effect on cabinet and ministerial durability, while the president’s power to dismiss cabinets does not affect cabinet durability but strongly increases ministerial durability (for details, see Supplementary Materials, Tables 9 and 10).

Conclusion

This controlled and comparative study demonstrates for the first time that institutional rules are an important explanatory factor for ministerial durability, an assumption sometimes alluded to, but never previously demonstrated. In particular, we show that the institutional instruments available to the president (especially the powers to dismiss cabinets and appoint ministers) affect the time that a minister remains in office to the magnitude and significance of some of the most important and well-understood determinants of ministerial duration, such as the minister’s political experience or the portfolio held. We also reassess previous findings on cabinet duration of the effect institutional rules have on non-electoral cabinet replacements, extending these by showing the individual and interactive effects of presidential powers to dismiss cabinets and to appoint ministers. Finally, by using a double comparative perspective on cabinets and the ministers who populate them, we also show that some institutional rules influence the risk of cabinet and ministerial terminations in different directions.

Our findings have important implications for studies on cabinet survival, ministerial careers, and institutional choice. First, we show that the effect of institutional rules on cabinets and ministers goes beyond the common focus on the mode of presidential elections, which serves as one of the major features of differentiation between parliamentary and semi-presidential systems. Second, for cabinet and ministerial terminations, it is important to consider the powers that are granted to the president. These findings provide new opportunities to study ministerial durability and support recent efforts to integrate the constitutional framework within which cabinets operate into explanations of government survival (Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Müller, Strøm and Bergman2008; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000059.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Michael Edinger, Svitlana Chernykh, and Matthew Kerby for their suggestions on earlier versions of this article and very gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of the editors and three anonymous referees. All errors that remained are ours. Part of the data collection was conducted by Elena Semenova during her stay as a visiting scholar in the Centre of European Studies at the Australian National University. She gratefully acknowledges the generous support provided by the Centre of European Studies. The authors also very grateful to the scholars who have generously shared their data on ministers in Eastern European countries or have provided help with data collection and coding: Mindaugas Kuklys (Latvia and Lithuania), Vello Pettai (Estonia), Malgorzata Jasiecka (Poland), Alzbeta Bernardyova (Czech Republic), Laurențiu Ștefan (Romania), Gabriella Ilonszki (Hungary), Bela Keszegh (Slovakia), Ana Železnik (Croatia), and Uroš Pinteric (Slovenia).