Introduction

Deliberative minipublics are increasingly called upon to engage with complex and contentious political issues, ranging from electoral reform in Canada, to abortion in Ireland, and climate change policy in the UK and France (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Farrell, Geißel, Grönlund, Mockler, Pilet, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021; Dryzek et al., Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti, Fishkin, Farrell, Fung, Gutmann, Landemore, Mansbridge, Marien, Neblo, Niemeyer, Setälä, Slothuus, Suiter, Thompson and Warren2019). These minipublics have often emerged in response to widespread dissatisfaction with the existing representative system (Elstub and Escobar, Reference Elstub and Escobar2019; OECD, 2020). In fact, it is often suggested that minipublics can help foster public approval of political decision-making, also on difficult issues (Kuntze and Fesenfeld, Reference Kuntze and Fesenfeld2021; Warren, Reference Warren, Warren and Pearse2008; Werner and Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). For instance, a majority of the French population reported being in favour of the climate change measures proposed by the 2020 Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat (Giraudet et al., Reference Giraudet, Apouey, Arab, Baeckelandt, Bégout, Berghmans, Blanc, Boulin, Buge, Courant, Dahan, Fabre, Fourniau, Gaborit, Granchamp, Guillemot, Jeanpierre, Landemore, Laslier, Macé, Mellier, Mounier, Pénigaud, Póvoas, Rafidinarivo, Reber, Rozencwajg, Stamenkovic, Tilikete and Tournus2022).Footnote 1

Yet, in current times of increasing worries about polarized and polarizing societies, one might ask: can minipublics perform a similar task in difficult contexts? Not only is this an important question in societies where polarization is already well established, but it is one that becomes more widely pertinent as there is widespread concern that a growing number of previously non-polarized societies come to be characterized by ideological divisions and deep dislike towards those in other political groups (Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2019; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012, Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018). As such, there is a need to test whether, and to what extent, minipublics are perceived as legitimate inputs into democratic decision-making by polarized citizens in order to better understand the contribution that minipublics can make to contemporary democracies.

So far, little is known about the role of minipublics in bolstering the perceived legitimacy of political decision-making in divided, polarized contexts. Many empirical studies to date gauge citizens’ reactions to hypothetical minipublics, and with only some of them considering a contentious issue such as migration (e.g., Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2022; Werner and Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). These are, however, about polarizing issues, and not necessarily about polarized citizens. Arguably, it is the views, and indeed behaviour, of these polarized citizens that constitute the toughest test for democratic decision-making in general. Moreover, the few to study minipublics in a polarized setting often do so without examining the effect of different forms and individuals’ degree of polarization (Garry et al., Reference Garry, Pow, Coakley, Farrell, O’Leary and Tilley2022; Pow, Reference Pow2021). Consequently, we lack insights into how minipublics are perceived by highly polarized citizens, and to what extent these perceptions differ for more moderate citizens.

This study builds on previous work investigating the perceived legitimacy of minipublics in a heterogeneous wider public (e.g., Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2022) and innovates in two ways. First, we outline a novel theoretical argument as to whether and why polarized citizens would perceive minipublics as less legitimate than more moderate citizens would. Previous studies indicate that polarized citizens are less willing to compromise (e.g., Hetherington and Rudolph, Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2015), more eager to participate in politics (e.g., Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008) and more reluctant to trust their political opponents (e.g., Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018). Given some of the key features of minipublics – such as their promotion of common ground, the relatively small number of citizens eligible to take part, and the diverse range of views and backgrounds represented – we therefore argue that polarized citizens may be more sceptical towards minipublics and their outcomes compared to more moderate citizens.

Second, using original survey data, we test our argument in Northern Ireland (n = 932), where respondents were informed about an actual minipublic on the contentious issue of the region’s constitutional future – on how joining a united Ireland would compare and contrast to the status quo of staying in the UK. This presents us with a highly polarized case study: Northern Ireland is a deeply divided society with a long history of affective and ideological polarization along ethno-national lines (Garry, Reference Garry2016; Tam et al., Reference Tam, Hewstone, Kenworthy and Cairns2009). Because of these fundamental divides, and the inherently contentious nature of the issue considered by the minipublic, the case under study allows for a solid test of the perceived legitimacy of deliberative minipublics in a context where polarization is rife and where the issue discussed is highly divisive and left unresolved for many years.

We find that higher levels of ideological polarization and, to an extent, higher levels of affective polarization are associated with lower levels of perceived minipublic legitimacy among the general public; those who did not participate in the minipublic themselves. At the same time, levels of perceived minipublic legitimacy were lower but not necessarily low among polarized citizens. This paper first and foremost contributes to a better understanding of how the perceived legitimacy of minipublics is shaped by the setting in which it takes place, in particular by the extent to which it is characterized by high levels of mass polarization. In addition, our findings present empirical insights on the consequences of polarized attitudes – that is, it suggests that polarization matters for the way in which citizens evaluate democratic tools and practices. Overall, the present study sheds new light on the merits and drawbacks of using deliberative minipublics in highly polarized settings.

The perceived legitimacy of deliberative minipublics

A deliberative minipublic brings together a small group of citizens, usually between ten and several hundred. They are invited on a (stratified) random basis as to broadly reflect the composition of wider society, representing diverse backgrounds and viewpoints that exist in the broader population (Brown, Reference Brown2006; Farrell and Stone, Reference Farrell, Stone, Thomassen and Rohrschneider2020). The participating citizens assemble to engage with expert information, take part in facilitated group discussions and come up with recommendations on a political issue (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Farrell, Geißel, Grönlund, Mockler, Pilet, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021; Smith, Reference Smith, Geißel and Newton2014). Common examples of minipublics include citizens’ juries, consensus conferences, deliberative polls and citizens’ assemblies.

Previous research on minipublics has often focused on the extent to which minipublics put ideals of deliberative democratic theory into practice, and typically looks at the small group of citizens participating within deliberative forums. Notably, some have suggested that minipublics can have a de-polarizing effect among the participating citizens (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Dryzek, Ercan, Hendriks and Niemeyer2017; Dryzek et al., Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti, Fishkin, Farrell, Fung, Gutmann, Landemore, Mansbridge, Marien, Neblo, Niemeyer, Setälä, Slothuus, Suiter, Thompson and Warren2019; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). Specifically, previous work indicates that deliberative forums can converge participants’ opinions on the issue(s) at stake as well as moderate participants’ feelings towards those from other groups (Barabas, Reference Barabas2004; Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, Reference Caluwaerts and Reuchamps2014; Fishkin et al., Reference Fishkin, Siu, Diamond and Bradburn2021; Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund, Herne and Setälä2015; Himmelroos and Christensen, Reference Himmelroos and Christensen2014; Setälä et al., Reference Setälä, Christensen, Leino and Strandberg2021; but see Luskin et al., Reference Luskin, O’Flynn, Fishkin and Russell2014).Footnote 2 The present paper moves beyond this line of research in two important ways: It reverses the logic by investigating the extent to which mass polarization influences the perceived legitimacy of minipublics, and it shifts the focus from minipublic participants to those outside the forum.

In recent years, the academic debate on minipublics has increasingly looked at the population at large (e.g., Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2022; Werner and Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). With minipublics being used more and more often (OECD, 2020), many citizens find themselves in a situation where a minipublic provides recommendations on their behalf. It is therefore important to consider the extent to which the general public perceives minipublics as a legitimate input into democratic decision-making.

What does it signify for the wider public to perceive democratic tools, including minipublics, as legitimate? Political legitimacy can be defined as ‘rightfully holding and exercising political power’ (Gilley, Reference Gilley2006, p. 500) and which is grounded in considerations such as it being just, fair, proper, correct, and appropriate (Beetham, Reference Beetham1991; Gilley, Reference Gilley2006; Tyler, Reference Tyler1990). It does not only relate to who is in power and how it is exercised, but also what outcomes it delivers (Beetham, Reference Beetham1991; Parkinson, Reference Parkinson2006). In political science, moreover, the focus is typically on citizens’ perceptions rather than normative standards – that is, on the extent to which a political leader, institution or system is perceived to be legitimate in the eyes of citizens (following Weber; see Beetham, Reference Beetham1991). Applied to our purpose here, perceived minipublic legitimacy is therefore defined as citizens’ beliefs about the rightfulness of minipublics and the extent to which their outcomes should be accepted (for a similar approach, see for instance Jäske, Reference Jäske2019; Werner and Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018).

Existing studies indicate that, on average, people tend to be fairly positive when evaluating minipublics and their outcomes (e.g., Gastil et al., Reference Gastil, Rosenzweig, Knobloch and Brinker2016; Jacobs and Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2022; van Dijk and Lefevere, Reference van Dijk and Lefevere2022; Werner and Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). Yet, at the same time, these studies also suggest that there are variations in the perceived legitimacy of minipublics among different subgroups in society. For instance, citizens who are politically interested and those who are dissatisfied with the existing representative system are suggested to be more supportive of bodies of citizens selected by lot (Bedock and Pilet, Reference Bedock and Pilet2020, Reference Bedock and Pilet2021; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2020; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2022) – although the evidence is more mixed for minipublics in particular (Gherghina and Geißel, Reference Gherghina and Geißel2020; Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022; Pow et al., Reference Pow, van Dijk and Marien2020; Talukder and Pilet, Reference Talukder and Pilet2021; Walsh and Elkink, Reference Walsh and Elkink2021). In addition, some of these studies report that women, younger people, and less affluent citizens are also more favourable towards the use of minipublics (e.g., Talukder and Pilet, Reference Talukder and Pilet2021). As such, this body of literature indicates that there is heterogeneity in the population when it comes to attitudes towards minipublics: Some people will be more likely to view minipublics and their outcomes as legitimate, and others will be less likely to do so.

While these previous studies have provided important insights into the perceived legitimacy of minipublics, several have stressed the importance of taking account of the broader context in which they take place (Parkinson and Mansbridge, Reference Parkinson and Mansbridge2012; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017). In this paper, we consider the perceived legitimacy of minipublics in a highly polarized context. After all, in contemporary democracies, there is widespread concern about heightened levels of mass polarization and the challenges thereof to the perceived legitimacy of the existing representative system (Hetherington and Rudolph, Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2015; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Levitsky and Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Hence, given the growing use of minipublics, it is important to empirically consider the role that polarization may play in shaping the perceived legitimacy of these novel tools among the general public.

To date, we have little understanding of the relationship between polarization, minipublics and the wider public. Scholars and pundits alike are quick to point to the exemplary case of the Irish Citizens’ Assembly which resulted in the legalization of abortion (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Suiter and Harris2019; McKee, Reference McKee2018). While these accounts may attest that minipublics can help break political deadlock on a polarizing issue, the evidence is mostly anecdotal (O’Leary, Reference O’Leary2019). Moreover, they have focused on polarizing issues rather than polarized citizens – similar to the few empirical studies that examine perceived minipublic legitimacy on a divisive issue such as migration (Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2022; Werner and Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). Meanwhile, the few studies that look at minipublics in a highly polarized context do not look at the impact of different forms of polarization on perceived minipublic legitimacy (Garry et al., Reference Garry, Pow, Coakley, Farrell, O’Leary and Tilley2022; Pow, Reference Pow2021). All in all, we lack insights into the perceived legitimacy of minipublics among polarized citizens and how these perceptions differ from those held by more moderate citizens.

Perceived minipublic legitimacy among polarized citizens

Polarization is generally divided into ideological and affective varieties (Pew Research Center, 2014). Ideological polarization is based on issue positions; it refers to the distance between people’s positions on political issues or dimensions, such as the liberal-conservative or left-right divide, with debate as to whether this is increasingly the case in Western societies (Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Draca and Schwarz, Reference Draca and Schwarz2021; Fiorina et al., Reference Fiorina, Abrams and Pope2008). Affective polarization denotes that people become more extreme in their negative feelings and dislike of their ‘out-group’ and/or more extreme in their positive feelings towards their own identity-based ‘in-group’ (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012, Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Political allegiance is generally considered the most salient identity, and dislike of the political out-group oftentimes exceeds divides based on other characteristics such as region, language, ethnicity or religion (Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018). In sum, polarization is understood here as the distance between citizens from different political groups, either ideologically, affectively, or both.

In what follows, we outline three theoretical mechanisms as to whether and why deliberative minipublics may be perceived as less legitimate by ideologically and affectively polarized citizens compared to their more moderate counterparts.

A first mechanism pertains to cooperation and compromise. Polarized citizens are found to be less tolerant towards other political groups and their arguments (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; Mutz, Reference Mutz2002; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2009). Indeed, differences in partisanship are considered to cause such intense feelings that these turn into animosity and hostility towards the outgroup (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019), and those with strong partisan identities are shown to be less inclined to consider competing arguments from their outgroup as reasonable or worth considering (Strickler, Reference Strickler2018). Consequently, compromise and cooperation with those with dissimilar outlooks are suggested as almost unthinkable for polarized citizens (Hetherington and Rudolph, Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2015; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; Pew Research Center, 2014; but see Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2022). Yet, deliberative minipublics explicitly aim to facilitate discussions among diverse citizens based on mutual respect and reason-giving (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Farrell, Geißel, Grönlund, Mockler, Pilet, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021; Smith, Reference Smith, Geißel and Newton2014). According to deliberative democrats, deliberation encourages people to be reflective, open-minded, and willing to reconsider initial pre-deliberative positions, thereby helping to promote trade-offs, compromises, and the identification of common ground on a political issue (Chambers, Reference Chambers2003; Curato et al., Reference Curato, Dryzek, Ercan, Hendriks and Niemeyer2017; Dryzek et al., Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti, Fishkin, Farrell, Fung, Gutmann, Landemore, Mansbridge, Marien, Neblo, Niemeyer, Setälä, Slothuus, Suiter, Thompson and Warren2019). As such, polarized citizens could see deliberative efforts as potentially changing the minds of people like themselves and seeking mutual understanding and compromise on their behalf. This could make polarized citizens less – or not at all – inclined to perceive minipublics and their outcomes as legitimate.

A second mechanism relates to polarized citizens’ readiness for political engagement. The strength of one’s political viewpoints and identity has been shown to increase the frequency of political talk in everyday lives and spur political activism, such as, voting and campaign activities (Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Harteveld and Wagner, Reference Harteveld and Wagner2022; Iyengar and Krupenkin, Reference Iyengar and Krupenkin2018; Mason, Reference Mason2015; Pew Research Center, 2014; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). In fact, sparking political participation and engagement is ascribed in the literature to be a possible benefit of mass polarization (Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). However, deliberative minipublics are by design limited in scale: only a small fraction of the wider population is selected to take part (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Farrell, Geißel, Grönlund, Mockler, Pilet, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021; Parkinson, Reference Parkinson2006). This may be to the disapproval of polarized citizens. Polarized citizens’ readiness for political engagement may result in disappointment about minipublics when they learn that they cannot participate in the forum themselves (unless they receive an invitation by virtue of the selection procedure). This, again, leads us to suspect that polarized citizens will be more sceptical towards deliberative minipublics.

A third mechanism is about intergroup trust. Polarized citizens are found to be less comfortable interacting with those who hold different political viewpoints or affiliations (Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2022; Pew Research Center, 2014). In fact, polarized citizens are shown to be less keen on having people from their political outgroup as neighbours, friends or romantic partner for their children (Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2022; see Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019 for a review). Moreover, they are suggested to be less trusting of people with different partisan affiliations (Carlin and Love, Reference Carlin and Love2016; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018). However, a key feature of minipublics is precisely the bringing together of people from diverse backgrounds and political groups – that is, involving citizens with dissimilar perspectives and identities and with further variation in how strongly they hold their identities and opinions (Brown, Reference Brown2006; Curato et al., Reference Curato, Farrell, Geißel, Grönlund, Mockler, Pilet, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021; Farrell and Stone, Reference Farrell, Stone, Thomassen and Rohrschneider2020). Consequently, the wider public is faced with a situation wherein people like them come together to deliberate with people who hold competing perspectives and identities. In fact, previous works find that people’s trust in other citizens shapes the perceived legitimacy of minipublics (Bedock and Pilet, Reference Bedock and Pilet2021; del Río et al., Reference del Río, Navarro and Font2016; Talukder and Pilet, Reference Talukder and Pilet2021). Therefore, the inclusion of people who are presumably perceived as untrustworthy by the strongly polarized leads us once more to expect polarized citizens to be less favourably disposed towards minipublics.

In sum, based on polarized citizens’ aversion to compromise, their willingness to participate in politics, and their low levels of intergroup trust, we hypothesize:

The more citizens are ideologically polarized on the issue dimension at stake, the less legitimate they perceive deliberative minipublics to be (Hypothesis 1).

The more citizens are affectively polarized on the identity dimension at stake, the less legitimate they perceive deliberative minipublics to be (Hypothesis 2).

Finally, ideological and affective polarization are often understood to be distinct, but interconnected phenomena. Some scholars argue that the roots of polarization lie in ideological differences in issue-based positions (Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017), whilst others state that it is rather people’s identity and group-attachment that is at the core of mass polarization (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2021; Luttig, Reference Luttig2018; Mason, Reference Mason2018). Illustratively, Iyengar et al. (Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012) put forward that it is ‘affect, not ideology’ that is the primary driver behind mass polarization in Western publics, whereas Costa (Reference Costa2021) counters that it is ‘ideology, not affect’ that shapes citizens’ preferences for political representation. Therefore, we explore which type of polarization is more strongly associated with the perceived legitimacy of minipublics among the public at large.

Data and methods

Case selection

We use survey data collected in Northern Ireland, which may be considered highly polarized in both ideological and affective terms. Ideologically, citizens are polarized on the fundamental question of Northern Ireland’s constitutional status: on the one hand, unionists would like to see the region remain in the UK; nationalists, on the other hand, advocate Northern Ireland’s secession from the UK to unify with the Republic of Ireland. This ethno-national ideological dimension dominates electoral competition and structures the party system (Garry, Reference Garry2016).Footnote 3 It also extends into many people’s identity: not only do people hold unionist or nationalist views, but they also think of themselves as unionist or nationalist. The strength of this divide is reinforced by other group differences: unionists are overwhelmingly Protestant and tend to identify as British; nationalists are overwhelmingly Catholic and tend to identify as Irish (Garry, Reference Garry2016). Even though a rising number of citizens identifies with no religion or as ‘neither’ nationalist nor unionist (Hayward and McManus, Reference Hayward and McManus2019), inter-group prejudice and physical segregation are continued manifestations of affective polarization in the region (Ferguson and McKeown, Reference Ferguson, McKeown, McKeown, Haji and Ferguson2016; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Campbell, Hewstone and Cairns2007; Tam et al., Reference Tam, Hewstone, Kenworthy and Cairns2009).

Sample and data

We fielded our survey with Survation Footnote 4 in the summer of 2019. Eligibility was restricted to adults living in Northern Ireland, with quotas set for sex and age (n = 932). A description of our analytical sample and its similarity to the profile of the broader population can be found in online Appendix A.Footnote 5

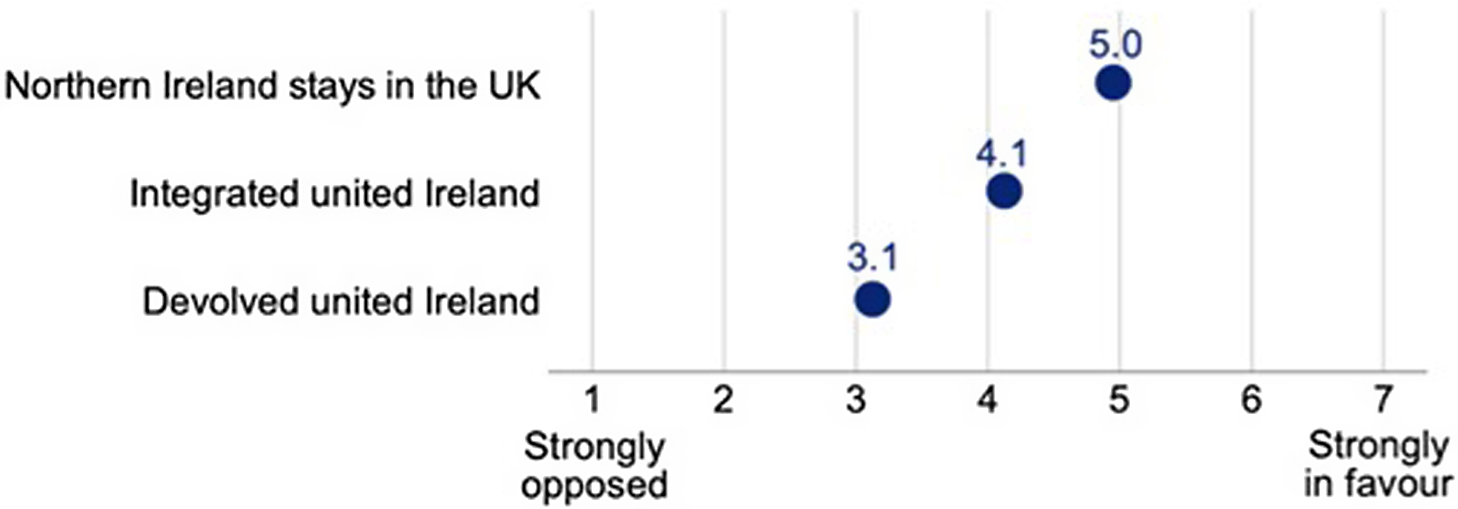

The survey was conducted soon after a minipublic was held (in March 2019) on the topic of Northern Ireland’s constitutional future and the various options of a united Ireland – joining as a devolved or integrated regionFootnote 6 – compared to staying in the UK.Footnote 7 In the minipublic itself, the participants heard evidence and arguments for the different models of a united Ireland, relative to the status quo, and at the end of the process they were asked to express their levels of support or opposition towards each constitutional option (Figure 1). The minipublic was held as part of an academic exercise and there was no media attention before or after the event. A report describing the minipublic and its outcomes was prepared for relevant policy-makers, but the minipublic did not have any formal decision-making function. The formulation of the survey items used can be found in online Appendix B.

Figure 1. The outcome of the minipublic on Northern Ireland’s constitutional future.

In our survey among non-participating citizens, we informed them about the minipublic’s proceedings and its outcomes. Recognizing that most people will be unfamiliar with the design features of minipublics, we produced an infographic to summarize this particular case (see Appendix B).Footnote 8 Figure 1 depicts the minipublic outcome as presented to the survey respondents.

Perceived legitimacy of minipublics

Afterwards, we measure the perceived legitimacy of the minipublic using two indicators (see also Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019; Werner and Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). First, we measure respondents’ general evaluation of the minipublic by asking them to what extent they believed the citizens’ assembly was just, trustworthy, inefficient, transparent, a waste of money and unnecessary. The items were asked in a randomized order, and on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 ‘Not at all’ to 10 ‘Completely’. Internal consistency proved high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82). After recoding the negative items, we combined the items into a general minipublic evaluation variable. Second, we measure the perceived legitimacy of the outcome by asking respondents how willing they were to accept the outcome of the citizens’ assembly. This was again measured on an 11-point scale whereby 0 means ‘Not at all willing’ and 10 ‘Completely willing’.

Ideological polarization

Ideological polarization is studied here at the individual level, as a degree of division at a certain point in time.Footnote 9 A common approach taken by scholars to measure ideological polarization in this fashion is to look at the constraint or consistency of people’s opinions (Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2016; Mason, Reference Mason2018; Pew Research Center, 2014). This is regarded to indicate ideological thinking and the extent to which people consistently find themselves on one side of an ideological divide. In doing so, it is important to not only look at citizens’ opinions towards one side of the divide (e.g., conservative or right-wing stances), but also at their opinions that fall on the other side of the divide (e.g., liberal or left-wing stances; Mason, Reference Mason2018).Footnote 10

To measure their issue positions, respondents were asked to what extent they were in favour of different options for the constitutional future of Northern Ireland – after they were told about the minipublic but before presenting them with the outcome. This was measured on a 7-point scale where 1 means ‘Strongly opposed’ and 7 ‘Strongly in favour’.

Using this question on issue positions, we compute our measure of ideological polarization by taking the absolute distance between respondents’ position towards Northern Ireland staying in the UK and their position towards forming an integrated united Ireland.Footnote 11 For example, a respondent scoring a 7 on staying in the UK and a 2 on an integrated united Ireland is assigned a score of 5, whereas someone who takes the middle option on the latter is assigned a score of 3. Our resulting measure of ideological constraint ranges from 0, meaning that respondents are not at all ideologically constrained to 6, meaning that respondents are extremely ideologically constrained on this issue.

Affective polarization

Affective polarization is typically measured through so-called feeling thermometers, which ask respondents to indicate how they feel towards different political groups on a scale of 0 (coldest, most unfavourable) to 100 (warmest, most favourable) (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2016). The extent to which respondents are affectively polarized is computed by subtracting the thermometer score individuals assign to their out-group from their in-group score (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). Political identity is oftentimes defined on the basis of partisanship (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018). However, it can also denote ideological group-attachments, such as liberals and conservatives or left-wingers and right-wingers (Devine, Reference Devine2015; Mason, Reference Mason2018), or it can even relate to more specific issue positions, such as supporters or opponents of certain policies (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021; see Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021 for a more elaborate account of these conceptions of political identity).

In this study, we employ feeling thermometers to measure affective polarization based on respondents’ feelings towards others with varying ethno-national identities. After asking respondents about their attitudes towards the minipublic, they were asked whether they usually think of themselves as unionist (generally in favour of staying in the UK), nationalist (generally in favour of leaving the UK to join a united Ireland), or neither. Next, we presented them with the above-described feeling thermometers.

We compute respondents’ level of affective polarization following the in-group minus out-group computation (e.g., Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). More specifically, for nationalist respondents, we subtract their rating of people from a unionist background (out-group) from their rating towards people from a nationalist background (in-group). Conversely, for unionist respondents, we subtract their rating of people from a nationalist background from their rating of people from a unionist background. For respondents who identified as neither unionist nor nationalist, we take their rating towards people from neither background (in-group) and subtract from this their least liked group rating – that is, the lowest score given to people from a unionist or nationalist background.Footnote 12 We divide this measure by ten so that our affective polarization measure ranges from 0, meaning respondents are not at all affectively polarized to 10, meaning that respondents are very much affectively polarized.Footnote 13

Control variables

In our models, we control for respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, that is, their sex, age, education level and community background (Garry et al., Reference Garry, Pow, Coakley, Farrell, O’Leary and Tilley2022; Walsh and Elkink, Reference Walsh and Elkink2021). We furthermore control for respondents’ satisfaction with democracy and political interest, as these are oftentimes associated with the perceived legitimacy of minipublics (e.g., Bedock and Pilet, Reference Bedock and Pilet2020; Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007).

Results

We start with some descriptive results of the wider public’s evaluations of the minipublic under study (Figure 2). For both types of polarized attitudes, respondents in the lower and middle categories seem to have somewhat similar outlooks on the minipublic and its outcome: They evaluate the minipublic rather favourably and indicate to be willing to accept its outcome, with the mean differences between them appearing to be modest. Instead, the most pronounced difference is between respondents in those two groups and those with the higher scores on the ideological or affective polarization scales. We observe that respondents who are the most ideologically or affectively polarized perceive the minipublic and its outcome as less legitimate than those being moderately or weakly polarized – by between 0.3 and 1.1 points on eleven-point scales. As such, the perceived legitimacy of the minipublic seems to vary somewhat across respondents with different scores on our ideological and affective polarization measures.

Figure 2. Descriptive statistics of the perceived legitimacy of the minipublic by level of polarization.

Note: Means in bars, 95% confidence intervals in error bars. Categorization of polarized attitudes is scale-based.Footnote 14 The corresponding table can be found in online Appendix; Table C1.

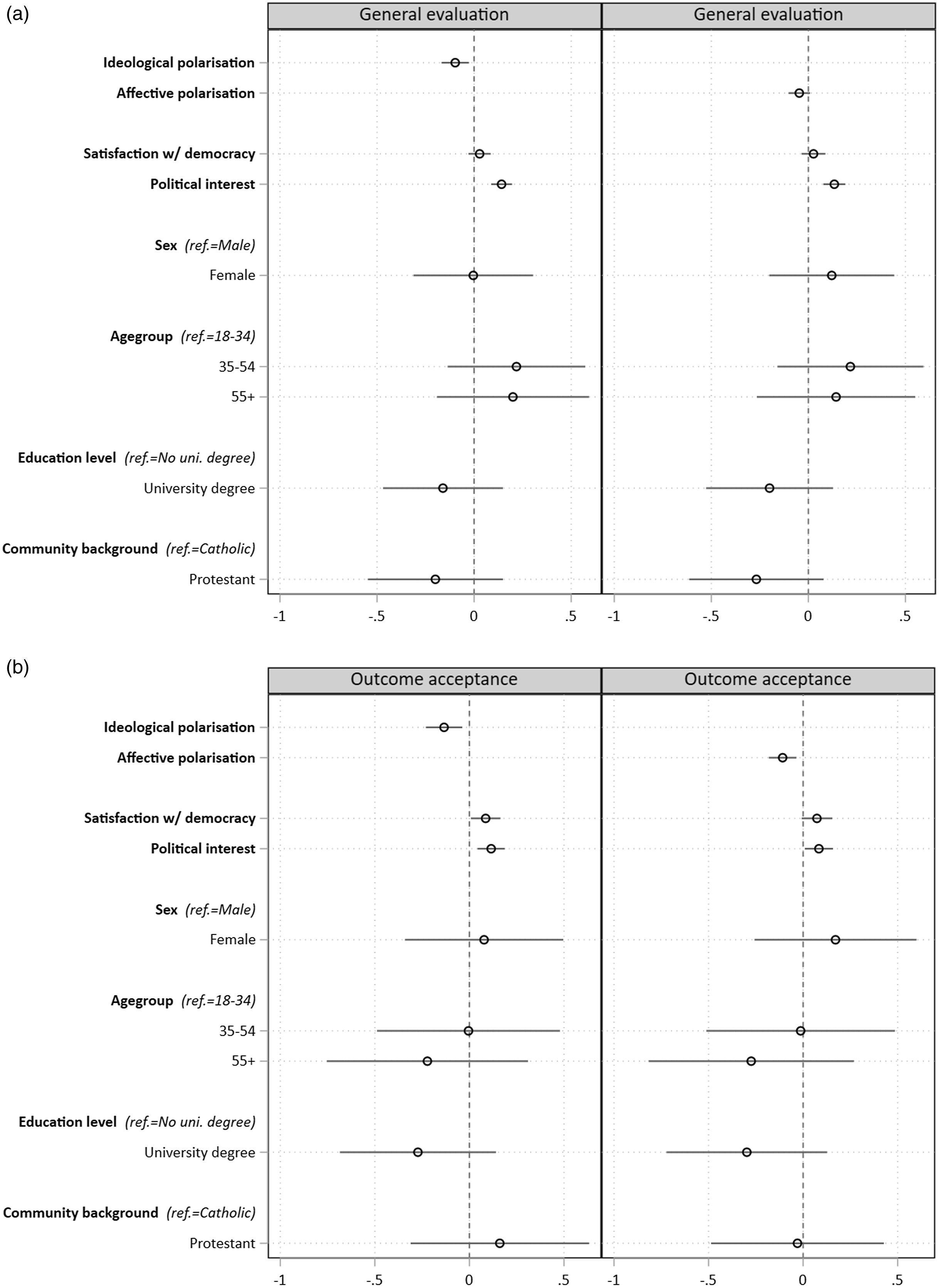

Next, we turn to our multivariate analysis to examine whether the extent to which individuals are polarized shapes the extent to which they perceive the minipublic and its outcomes to be legitimate (Figure 3). First, we look at ideological polarization and we observe a negative and statistically significant relationship with minipublic legitimacy perceptions (H1). Indeed, we find that the more an individual is ideologically polarized, the more negative the general evaluations of the minipublics and the lower the willingness to accept its outcome. A one-point increase in ideological polarization (on a seven-point scale) is associated with approximately a one-point decrease in the perceived legitimacy of the minipublic and its outcome (on eleven-point scales).

Figure 3. OLS Regression predicting the perceived legitimacy of the minipublic.

Note: Estimates of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression models with unstandardized coefficients in markers and 95% confidence intervals in spikes. Models include controls for further categories of Sex, Education level and Community background, which are not displayed for reasons of readability. Corresponding tables can be found in Appendix; Table C2. N1 = 757; N2 = 709; N3 = 866; N4 = 823.

In turn, when we consider affective polarization, we observe that it also appears to be negatively related to minipublic legitimacy perceptions, but this reaches statistical significance only for outcome acceptance (H2). In other words, the more an individual is affectively polarized, the lower the willingness to accept the minipublic outcome. More specifically, a one-point increase in affective polarization (on an eleven-point scale) is associated with about a one-point decrease in outcome acceptance (also on an eleven-point scale).

To compare the size of effects for ideological and affective polarization, we look at the standardized regression coefficients (given that both are measured on different scales). For respondents’ general evaluation of the minipublic, we see that the association is stronger for ideological polarization than for affective polarization (standardized estimates of –0.104 and –0.062 (n.s.), respectively). For outcome acceptance, the association is similar in size for ideological and affective polarization (std. estimates of –0.100 and –0.102, respectively). Yet, effect sizes remain fairly modest overall.

Although not our primary focus, it is worth noting the effects, or indeed null effects, observed for our control variables. In Figure 3 we see that none of our demographic controls – sex, age, education level or community background – are significantly related to either people’s general evaluation of the minipublic or the extent to which they accept the outcome. Similarly, satisfaction with democracy does not predict general evaluations of the minipublic, although higher levels of satisfaction are significantly associated with higher levels of outcome acceptance in one instance. Political interest is the only control variable to display a consistently significant association with minipublic legitimacy perceptions: Individuals with higher levels of political interest have more positive general evaluations and higher levels of outcome acceptance.

Post hoc analyses

Why do polarized citizens tend to perceive minipublics and their outcomes as less legitimate? In additional post hoc analyses we shed more light on the mechanism at play. To do so, we run exploratoryFootnote 15 mediation analyses using respondents’ aversion to political compromise, their willingness to participate in the minipublic, and their trust in fellow citizens to participate in politics as mediating variables (see online Appendix; Table B4 for item formulations). Results seem to indicate that respondents’ willingness to participate and trust in other citizens may be associated with perceived minipublic legitimacy, but not with polarized attitudes. Interestingly, ideologically and affectively polarized citizens tend to be more averse to political compromise. In turn, aversion to compromise appears to be associated with lower levels of perceived minipublic legitimacy (see online Appendix D).

Robustness checks

To assess the robustness of our results, we conduct additional analyses. First, we examine whether our results are robust against different specifications of our polarization measures. We base our measurement of ideological polarization on respondents’ issue extremity, both in absolute and relative terms (Mason, Reference Mason2015, Reference Mason2018). We also consider alternative measurements of affective polarization, where we compute the out-group for those who identify as neither unionist nor nationalist as the average of their thermometer ratings for unionists and nationalists. We furthermore re-run our analysis to include the small amount of respondents for whom our computation of affective polarization resulted in a negative value (i.e., more dislike towards the in-group than towards the out-group; n = 68). See online Appendix E for further information on these measurements. When doing so, we see that the observed association between polarized attitudes and perceived minipublic legitimacy is robust against different specifications (Appendix; Tables E1-E2).

Second, we test whether it matters if respondents are part of one side of the divide (more favourable towards staying in the UK; Unionists), the other (more favourable towards an integrated united Ireland; Nationalists) or neither (Neithers) – despite the fact that the minipublic was part of an academic exercise rather than being part of any binding political decision-making.Footnote 16 When computing the regression analyses for the different groups separately, it seems that the effect sizes differ quite substantiallyFootnote 17 but that the direction of the results remains generally negative (Appendix; Tables E3-E4). Hence, regardless of which side of the divide an individual is situated, polarization tends to be negatively associated with perceived minipublic legitimacy.

Third, in our main analysis, we present a complete case analysis – whereby ‘don’t know’ responses are treated as missing values (see Appendix Table F1 for an overview of missingness per variable). Yet, this list-wise exclusion ignores their responses and may result in bias and imprecision in the results reported in our main analyses (van Buuren, Reference van Buuren2018). To address this concern, we run Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE). A more detailed explanation of this method can be found in online Appendix F. When examining the pooled results of our multiply-imputed datasets, we again come to similar conclusions about polarized citizens perceiving minipublics as slightly less legitimate than moderate citizens (Appendix; Table F3).

Conclusion

Deliberative minipublics ask a small group of citizens to provide recommendations on a political issue, and they are often considered to bolster public approval of political decision-making (van der Does and Jacquet, Reference van der Does and Jacquet2021). But can they do so in a context where polarization is rife? While recent studies highlight that different citizens have different outlooks on minipublics (e.g., Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2022), it remains unclear how minipublics are perceived by highly polarized citizens. Our key finding – that higher levels of ideological polarization and, to an extent, higher levels of affective polarization, are generally associated with lower levels of the perceived legitimacy of minipublics – presents a novel contribution to our knowledge of both deliberative minipublics and, indeed, polarization. In this final section we reflect on our results in the context of the relevant literature and highlight a number of avenues for further research.

On the one hand, our findings suggest that deliberative minipublics may contribute to perceived legitimacy in highly polarized contexts. While differences between citizens holding different levels of polarization are significant, the magnitude of these differences is not large. Indeed, among citizens with higher levels of both ideological and affective polarization, mean general minipublic evaluations and mean levels of outcome acceptance were close to or above the midpoint of each scale. In other words, levels of perceived minipublic legitimacy were lower but not necessarily low among these citizens compared to their more moderate counterparts.

Yet, while the magnitude of the effect of polarization found in the present study is ultimately small, we suggest this is likely to reflect the nature of the minipublic used in our study: purely advisory rather than binding, resulting in a poll rather than clear-cut recommendation, and organized by academics rather than a government or parliamentary body. This may be considered a constraint to some extent, given that many minipublics are initiated by official actors to provide policy recommendations and we can imagine that such minipublics are more likely to be politicized (Setälä, Reference Setälä2017), with polarization in turn shaping legitimacy perceptions to a greater extent. At the same time, this in itself should cause us to reflect on the potential value of minipublics that are not coupled with formal institutions, but rather initiated by academic researchers or civil society organizations and tasked to reflect rather than advise on a contentious issue – particularly in polarized settings.

On the other hand, our findings also suggest caution in the use of minipublics in polarized settings. One of the core features of deliberative minipublics is that they bring together a diverse range of citizens from the wider public. Just as the diversity of citizens is recognized in the rationale and selection mechanism of these novel tools, so too is it important to recognize the potential heterogeneity in the attitudes that non-participating citizens hold towards them. In our particular case, the fact that citizens who are more polarized have significantly lower legitimacy perceptions of minipublics illustrates that such instruments should be used cautiously in such settings and on contentious issues. This suggests that the context in which a deliberative minipublic is held matters a great deal, echoing Parkinson and Mansbridge (Reference Parkinson and Mansbridge2012) and Setälä (Reference Setälä2017).

This raises an important question: does it matter if some groups in society are particularly supportive of minipublics and their outcomes while others are significantly less so? In order to more fully appreciate just how much any heterogeneity in legitimacy perceptions matters with respect to polarization, we would need to consider not just perceptions towards minipublics but also citizens’ perceptions of other modes or elements of political decision-making. In our observational study we did not incorporate this comparative dimension, but other experimental studies do suggest that minipublic legitimacy perceptions match or exceed those of more conventional institutions and representative processes (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; Jacobs and Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Werner and Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). Additional research is needed to systematically investigate any significant variation in citizens’ legitimacy perceptions of minipublics relative to other forms of decision-making. This could, moreover, shed further light on the role of minipublics in feeding into policy-making, especially as outcome favourability may be of particular importance to polarized citizens. Future qualitative research might set out to map polarized citizens’ reasons to be in favour or against minipublics, whilst more experimental work is needed to shed more light on the causal mechanisms at play. This way, we can learn more about generating public acceptance of political decisions, especially in the case of difficult and divisive topics.

Having emphasized the role that a particular context plays in assessing attitudes towards minipublics, we conclude with more general implications arising from our results. Firstly, while Northern Ireland has a long history of polarization, and thus may be considered an extreme case, it is far from unique. On the one hand, Northern Ireland itself has changed markedly since the signing of its major peace agreement over two decades ago, with a significant minority of people looking beyond the traditional ethno-national divide and without a strong degree of attachment to established political parties (Hayward and McManus, Reference Hayward and McManus2019). On the other hand, Northern Ireland remains deeply divided between different ideologies and groups (Garry, Reference Garry2016). Taken together, we suggest that Northern Ireland has moved in the direction of becoming more like other ‘normal’ democracies, at least to some extent, while at the same time many of the cases we typically assign to the latter category increasingly display signs of the kind of polarization observed in Northern Ireland. Therefore, we argue that our key finding on the role of polarization in shaping minipublic legitimacy perceptions should be considered by scholars and organizers of minipublics on contentious issues or in other polarized settings, including those where polarization is a relatively recent phenomenon.

Finally, in line with research on polarized citizens showing, for instance, less tolerance and willingness to compromise, we connect these views to the way people evaluate political processes and outcomes. We highlight that one general effect of polarization is that both ideologically and affectively polarized citizens can perceive democratic decision-making to be less legitimate than more moderate citizens. Given widespread concern about heightened levels of polarization in many democracies, political scientists face the twin task of further probing consequences for democratic government, together with how these effects may be mitigated and not exacerbated. In this regard, we must pay careful attention to heterogeneous citizens’ attitudes towards different forms of democratic decision-making as well as, indeed, how different forms of democratic decision-making may shape citizens’ attitudes one way or the other.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000649.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made openly available after publication.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. We would also like to thank those who offered feedback in the 2021 PSA General Conference (online), 2021 APSA General Meeting (online) and the 2021 ECPR General Conference (online) as well as the members of the LEGIT Research Group at KU Leuven for their helpful insights on various drafts of this paper.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement no. 759736). This publication reflects the authors’ views and that the Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Disclosure of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval Statement

This study was approved by the KU Leuven Research Ethics Committee (G-2018 11 1409). All respondents provided informed consent prior to enrolment in the study.