Introduction

The pervasive decline of voter turnout rates in many advanced democracies and the social and political tensions that this trend poses have been well-documented in contemporary political science research (Blais and Rubenson, Reference Blais and Rubenson2012). Adding to this, today, weak electoral mobilisation among voters with immigration or minority backgrounds further challenges principles of democratic governance (Simonsen, Reference Simonsen2020; Bevelander and Hutcheson, Reference Bevelander and Hutcheson2021). Crucially, the systematic political disengagement among these groups raises serious questions about the quality of democratic representation in host societies (Blatter et al., Reference Blatter, Schmid and Blättler2017). This paper investigates the political participation gaps between native citizens and those with an immigration background and studies the impact of local non-citizen voting (NCV) rights policies on these electoral participation dynamics.

In earlier studies, turnout differences between citizens are often understood by referring to socio-economic cleavages, education, demographic, socio-political and cultural factors (Smets and van Ham, Reference Smets and Van Ham2013). Yet, when it comes to explaining weaker turnout amongst individuals with an immigration background, there is a growing consensus that bottom-up explanations, relying on individual characteristics, do not suffice (Bass and Casper, Reference Bass and Casper2001; Simonsen, Reference Simonsen2020; Filindra and Manatschal, Reference Filindra and Manatschal2020; Bratsberg et al., Reference Bratsberg, Ferwerda, Finseraas and Kotsadam2021). In particular, it seems that inclusive local integration policies have the potential to narrow the turnout gaps between natives and individuals with an immigration background (Gonzalez-Ferrer and Morales, Reference Gonzalez-Ferrer and Morales2013; Filindra and Manatschal, Reference Filindra and Manatschal2020). However, after decades of research on the topic of immigrant political representation, only a handful of studies have addressed the local policy context as a determinant of immigrant turnout (Jones-Correa, Reference Jones-Correa2001; Ramakrishnan and Espenshade, Reference Ramakrishnan and Espenshade2001). Thus, there remains a critical unexplained variation in why turnout gaps between natives and citizens with immigration backgrounds look different within and between countries.

We propose NCV rights as one possible local policy factor influencing such turnout differences. In this way, our paper also speaks to the ongoing debate in the literature and political practice on immigrant political participation, which sees NCV rights policies and naturalisation as two alternative pathways to immigrant political integration. Whereas previous studies have shown that naturalisation boosts the political incorporation of immigrants (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Pietrantuono2015), the evidence regarding NCV rights remains scarce – which we aim to address in this study. Despite increasing interest in the topic in recent years (Stutzer and Slotwinski, Reference Stutzer and Slotwinski2020; Kayran and Erdilmen, Reference Kayran and Erdilmen2021), the precise political and electoral consequences of NCV rights have not been well-understood, with few notable exceptions (Ruedin, Reference Ruedin2018; Engdahl et al., Reference Engdahl, Lindgren and Rosenqvist2020; Ferwerda et al., Reference Ferwerda, Finseraas and Bergh2020). Here, we expand the study of the impact of NCV rights on voter turnout beyond its effects on non-naturalised immigrants and concentrate on citizens. More specifically, we investigate the political participation gaps between native citizens and citizens with an immigration background and evaluate to what extent NCV rights policies provide (positive) externalities in turnout among individuals who are not directly targeted by this policy.

Our theoretical framework is two-fold. First, we expect stronger political mobilisation among natives and citizens with an immigration background living in municipalities with NCV rights. We suggest that either a mechanism of ‘power-dilution’ threat, due to an increase in the electoral supply from non-citizens obtaining voting rights (Stutzer and Slotwinski, Reference Stutzer and Slotwinski2020), or an enhanced democratic engagement, through communal or individual-level political socialisation, could explain why local enfranchisement of non-citizens spills over to advancing turnout among citizens (Stadlmair, Reference Stadlmair2020; Bratsberg et al., Reference Bratsberg, Ferwerda, Finseraas and Kotsadam2021). Second, we look at the citizens in two so-called ‘voter blocks’, distinguishing between natives and citizens with immigration backgrounds (Bergh and Bjorklund, Reference Bergh and Bjorklund2011). This is because citizens with an immigration background carry both an inherited minority group identity and an acquired attachment to the majority group and have access to political rights and other privileges through their citizenship status, making them distinct from both native citizens and non-citizen immigrants (Schlenker, Reference Schlenker2016; Strijbis and Polavieja, Reference Strijbis and Polavieja2018; Politi et al., Reference Politi, Chipeaux, Lorenzi-Cioldi and Staerklé2020). We posit that citizens with an immigration background will be especially activated by this turnout boost due to NCV rights policies, arguing that such enfranchisement dynamics raise the salience of the topic of immigrant political influence and representation at the local level.

To assess the effect of local non-citizen enfranchisement policies on the electoral turnout for citizens – with and without an immigrant background – we focus on Switzerland, which hosts one of the largest foreign-born populations in Europe. The Swiss case is particularly fitting for this study because of the natural within-country and over time variations of non-citizen enfranchisement rules. It, therefore, allows us to have a research design suited to rule out country, local, and individual level idiosyncrasies that can potentially confound the relationships we are interested in. Empirically, we rely on longitudinal high-quality household panel data, that is the Swiss Household Panel (SHP), from 1999 to 2014. In addition, we collect local level data on the introduction of NCV rights across Switzerland over time and match this with the SHP at the household level using municipal registry codes. In our analyses, we conceptualise and measure ‘citizens with an immigration background’, based on the Swiss government’s official definition. Our term of citizens with an immigration background includes all naturalized citizens and Swiss citizens by birth whose parents were born abroad.Footnote 1

Our findings suggest that while non-citizen enfranchisement boosts participation across all citizens, citizens with immigration backgrounds are more reactive to the NCV rights in terms of higher turnout. In this way, the paper adds a critical nuance to individual-based explanations when making sense of why voters with immigration backgrounds participate less in formal electoral processes in host societies. This means that local policies imply spill-over effects by enhancing the political participation of individuals who do not personally gain from such policies themselves.

Political participation and NCV rights in the literature

While the existence of a clear gap in political participation between natives and citizens of immigrant origin is uncontested, the precise reasons are still debated (Bird et al., Reference Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011; Gonzalez-Ferrer and Morales, Reference Gonzalez-Ferrer and Morales2013; Simonsen, Reference Simonsen2020; Bevelander and Hutcheson, Reference Bevelander and Hutcheson2021). On the one hand, studies focusing on individual resources emphasised that non-immigration related factors such as education, employment status, or income are most helpful in explaining the variation of political participation amongst citizens of immigrant origin (Cho, Reference Cho1999; Bevelander and Pendakur, Reference Bevelander and Pendakur2009). On the other hand, many have sustained that the turnout gap between individuals with immigration backgrounds and natives is better understood if, instead, variation within immigrant groups is considered such as their roots in the host country, language proficiency, country of origin and personal networks (Bass and Casper, Reference Bass and Casper2001; Wass et al., Reference Wass, Blais, Morin-Chassé and Weide2015; Ruedin, Reference Ruedin2018; Bevelander and Hutcheson, Reference Bevelander and Hutcheson2021). Yet, studies focusing on such political engagement gaps have paid scarce attention to the local context, institutions, and policy interventions that may alter these differences. Research on the local contextual antecedents of political engagement across immigrant-origin and native citizens remains relatively scarce – with only a few notable exceptions (Jones-Correa, Reference Jones-Correa2001; Ramakrishnan and Espenshade, Reference Ramakrishnan and Espenshade2001; Filindra and Manatschal, Reference Filindra and Manatschal2020; Manatschal et al., Reference Manatschal, Wisthaler and Zuber2020).

Despite this, both the local and national context in which voters live matter significantly regarding their political engagement (Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2017). For instance, differences in electoral rules between the states in the USA, such as laws regarding voter registration, poll closures, absentee ballots etc., seem to be related to turnout rates – particularly when it comes to underrepresented minority groups (Jones-Correa, Reference Jones-Correa2001; Ramakrishnan and Espenshade, Reference Ramakrishnan and Espenshade2001). Moreover, recent work reveals a link between local electoral institutions and turnout differences, where direct democracy rules boost political participation among residents of immigrant origin (Manatschal, Reference Manatschal2021). These findings reveal that political participation is linked to the local policy context in which voters are embedded. Therefore, further research, especially in non-USA contexts, is needed to investigate turnout gaps between voters with and without an immigration background, considering local policies and electoral institutions.

One such local electoral institution that has become increasingly common in democratic countries is local NCV rights (Earnest, Reference Earnest2015; Stutzer and Slotwinski, Reference Stutzer and Slotwinski2020; Kayran and Erdilmen, Reference Kayran and Erdilmen2021; Koukal et al., Reference Koukal, Schafer and Eichenberger2021). While earlier studies on non-citizen enfranchisement policies have added significantly to what we know about the timing and conditions of NCV rights, there is relatively scant attention paid to the political consequences of such electoral rules. Notable exceptions to this have been focused on the effect of local non-citizen enfranchisement on increasing social spending (Ferwerda, Reference Ferwerda2021) and studies investigating the direct turnout effects of enfranchisement among their target groups, that is non-citizens, showing weak engagement (Ruedin, Reference Ruedin2018). Others have also examined whether early access to voting rights among non-naturalised immigrants foster their political integration in the long run, providing mixed results (Ferwerda et al., Reference Ferwerda, Finseraas and Bergh2020; Engdahl et al., Reference Engdahl, Lindgren and Rosenqvist2020).

Crucially, earlier literature has concentrated on the consequences of NCV rights on non-naturalised immigrants almost exclusively. However, policies targeting non-citizen immigrant residents have externalities affecting citizens’ political responses, especially those with an immigration background (Filindra and Manatschal, Reference Filindra and Manatschal2020; Manatschal et al., Reference Manatschal, Wisthaler and Zuber2020). So far, research remains scarce on possible spill-over effects of NCV rights policies on voters beyond its direct scope, that is citizens. In this paper, we aim to address these gaps and investigate the influence of non-citizen enfranchisement legislation on citizens’ political participation dynamics, taking into account the heterogeneity within the electorate, that is, native citizens and citizens with an immigration background.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

The core premise of our theoretical framework is that where voting rights are extended to non-naturalised immigrants, turnout rates amongst all citizens – with or without immigration backgrounds – are expected to be higher. Based on extant studies, this could be explained by a perceived increase in competition for political influence (Stutzer and Slotwinski, Reference Stutzer and Slotwinski2020; Koukal et al., Reference Koukal, Schafer and Eichenberger2021) or could be the result of advanced social engagement due to the expansion of political rights (Förster, Reference Förster2008; Stadlmair, Reference Stadlmair2020). Furthermore, we also suggest that the positive effects of non-citizen enfranchisement on political participation will be more prominent for citizens with immigration backgrounds than native citizens since their connection to the immigrant representation makes them more sensitive to the debates around NCV and increases the salience of the matter of immigrant political participation.

First, why should we expect citizens residing in areas with NCV rights to vote more than others? Based on earlier evidence, we identify two potential reasons for higher political participation among citizens who live in areas where non-citizens hold political rights. While both mechanisms can occur simultaneously within host democracies, they are, arguably, mutually exclusive at the individual level as they are based on two distinct logics of self-interested democratic grievances and group or individual based enhancement of political socialisation. Starting with the former, it is possible to consider non-citizen enfranchisement as equitable to an increase in the overall voter supply (Stutzer and Slotwinski, Reference Stutzer and Slotwinski2020; Koukal et al., Reference Koukal, Schafer and Eichenberger2021). Thus, such a rise in participation in non-citizen enfranchised areas can be seen as citizens’ attempt to counterbalance the rising voter supply from non-citizens. In this conception, higher electoral mobilisation serves to preserve their electoral voice and political influence. This seems to be entirely plausible, particularly when considering the evidence showing that the citizens have been the most resistant to introducing NCV rights in contexts where the share of such a population has been the greatest (Stutzer and Slotwinski, Reference Stutzer and Slotwinski2020; Kayran and Erdilmen, Reference Kayran and Erdilmen2021). Furthermore, in most Western democracies, introducing NCV constitutes a sizeable increase in electoral supply, making it challenging and a politically risky legislation to pass (Piccoli, Reference Piccoli2021).

In previous studies, a so-called ‘immigrant block’ voting behaviour has been typically shown to be more left-leaning and more redistributive when compared to the aggregate native citizen political choices (Strijbis, Reference Strijbis2014). While the consistency of such an electoral block is still debated (Bergh and Bjorklund, Reference Bergh and Bjorklund2011), various studies find strong evidence on citizens’ concerns about immigration and the perceived negative influence that immigrants may have on the host community and its political system (Hainmueller and Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2007; Semyonov et al., Reference Semyonov, Raijman and Gorodzeisky2008; Schlenker, Reference Schlenker2016). Moreover, citizens heavily overestimate the number of non-citizens living in their community (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov, Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2020). Thus, we argue that these concerns underpin the potential of such counterbalancing voting behaviour despite the low turnout of immigrant populations (Bird et al., Reference Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011; Ruedin, Reference Ruedin2018). This implies that an increase in turnout among citizens as a reaction to NCV legislation may occur (Stutzer and Slotwinski, Reference Stutzer and Slotwinski2020; Koukal et al., Reference Koukal, Schafer and Eichenberger2021), even though the actual numbers of non-citizens who eventually make use of these new political rights are low and consist of a heterogeneous set of preferences (Ruedin, Reference Ruedin2018).

However, this competition for representation and political influence logic may not be the (or the only) potential driver behind increased political participation in contexts with NCV rights. Concentrating on the activating role of inclusive electoral contexts, evidence from studies on Austria and Germany (both at the neighbourhood level) show that a higher share of electorally excluded non-citizens has a dampening effect on overall turnout (Förster, Reference Förster2008; Stadlmair, Reference Stadlmair2020). More specifically, Stadlmair finds evidence of a local contagion mechanism of participation where, in the presence of the electoral exclusion of a sizeable number of immigrant populations, citizens living in such areas are documented to participate less in elections due to a spatial lack of political interaction and subsequent non-engagement (Reference Stadlmair2020). Such diffusion of political socialisation at the local level could be argued to occur through the increased political exchanges between the residents due to the introduction of the policy. Alternatively, introducing NCV rights might increase mobilising activities in the community for turnout more widely (Ferwerda et al., Reference Ferwerda, Finseraas and Bergh2020; Bratsberg et al., Reference Bratsberg, Ferwerda, Finseraas and Kotsadam2021). Following this, an inclusive electoral context in the form of non-citizen enfranchisement policies may enhance political participation among citizens from a democratic enhancement perspective. This suggests that since NCV rights boost the inclusiveness of the democratic system by providing local electoral rights to non-naturalised immigrants, such an engagement effect will spill over to the citizens.

In sum, based on either a competition logic resulting from an increase in electoral supply or an enhanced democratic engagement mechanism, we expect political participation to be higher in municipalities with local NCV rights. We contend that these two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive within the populations studied, that is, some individuals enhance their participation through the competition mechanism whereas others through the democratic engagement logic. However, on the individual level, an increase in turnout of a voter cannot simultaneously be a product of the competition and the democratic engagement mechanism at the same time. Our first hypothesis reads as follows:

Hypothesis 1: In municipalities with non-citizen voting (NCV) rights, the overall political participation of citizens will be higher.

So far, we argued that local NCV rights are linked to overall higher political participation in such electoral inclusive municipalities – either due to enhanced political competition or democratic engagement. Now, we further nuance our theoretical framework by suggesting heterogeneous effects among different groups of citizens. More precisely, we suggest that the voters’ immigration background may condition both possible logics of such a boost in participation. Considering the heterogeneity of immigration background status among citizens, we distinguish two groups when thinking of the impact of local non-citizen enfranchisement policy: (1) native citizens without an immigration background who hold the host country’s citizenship from birth; and (2) citizens of immigrant origin who hold host country citizenship from birth but whose parents have immigrated and naturalised immigrants who have acquired host country citizenship by going through the process of naturalisation (i.e., first and second generation immigrant citizens). We put forward that particularly citizens with an immigration background are more likely to turn out in contexts with NCV rights because immigration-related policies and political debates related to immigration and integration are more salient for those citizens compared to natives.

Our expectation is based on a burgeoning body of research, suggesting that identity dynamics of citizens with an immigration background relate strongly in the context of their political behaviour and preferences (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Heath, Fisher and Sobolewska2014; van der Zwan, Reference Van Der Zwan2019). On the one hand, there is evidence from Germany demonstrating that immigration and economic circumstances are the most concerning issues for immigrants (Paul and Fitzgerald, Reference Paul and Fitzgerald2021). Principally, the importance attributed to those issues is significantly stronger than that held by native citizens. On the other hand, there is evidence that this enhanced salience of immigration-related issues directly influences immigrants’ political behaviour. For instance, van der Zwan shows that non-Western immigrants in the Netherlands are significantly less likely to support political parties that hold restrictive immigration policy positions, regardless of their economic situation (2019).

Likewise, in the British context, immigrants’ vote is heavily constrained by self-perception of discrimination experienced in the host community and how political parties ignore or fight against such discrimination (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Heath, Fisher and Sobolewska2014). Studies of Latino/a voters in the USA further support the argument that minority voters are more likely to cast their vote based on their and parties’ positions on the immigration dimension (Collingwood et al., Reference Collingwood, Barreto and Garcia-Rios2014). Hence, policies addressing immigration or integration issues, such as discrimination, politically engage immigrants and citizens with immigration backgrounds more substantially than native citizens. Consequently, we argue that NCV rights policies will have a similar effect. The presence of such inclusive electoral policies will enhance political participation of citizens with immigration backgrounds more strongly by raising the salience of the migrant participation and representation.

Hypothesis 2: Compared to native citizens, the positive impact of living in a local context with non-citizen voting rights on political participation will be stronger for citizens with an immigration background.

Data and method

For our empirical analyses, we use the Swiss Household Panel (SHP) data from 1999 to 2014.Footnote 2 The SHP is a high-quality longitudinal panel study of households residing in Switzerland that surveys samples of native Swiss citizens and naturalised and non-naturalised immigrants (FORS, 2019).Footnote 3 Our sample in the analyses consists of native citizens (NC), that is, respondents with Swiss citizenship from birth who have no immigration background or dual citizenship, and citizens with immigration background (CIB), that is, dual citizens and first and second-generation immigrants with Swiss citizenship. Since we are interested in the political participation of citizens living in municipalities (communes/Gemeinde) with and without NCV rights, we restrict our sample to Swiss citizens eligible to vote in all elections and at all geographic levels. Considering our theoretical framework, we combined the first-generation immigrants who obtained Swiss citizenship through naturalisation with second-generation immigrants born with Swiss citizenship whose parents were foreign-born into a single group of ‘citizens with immigration background’ (CIB), maximising the precision of our estimates given the small sample sizes of these groups. Robustness checks show that our results remain unchanged when disaggregating our group measurement specifically into these categories, see pp. 27–29 in the online appendix.

The Swiss case of NCV rights

According to Article 39 of the Swiss federal constitution, the legislation and implementation of rules over the acquisition of cantonal and municipal citizenship and opting in for non-citizen enfranchisement are the responsibility of the corresponding canton and municipality. Thus, federal institutional structures in Switzerland allow for a variation in NCV rights policies both between and within cantons. As of now, out of the twenty-six Swiss cantons, seven have adopted local NCV rights. This makes it a particularly fitting case for isolating the impact of such policies across cantons and municipalities. Moreover, our study’s temporal scope covers the legislation periods of these reforms since all cantons, except Jura, have introduced NCV rights in the 2000s. To measure non-citizen enfranchisement in our respondents’ local areas of residence, we merge our individual-level data with information on households’ residential locations at the municipal level. Using administrative municipal data codes (OFS), we match the SHP data with our coding of Swiss municipalities as positive or negative cases of NCV rights over time. Further details of the non-citizen enfranchisement legislation and reform efforts in Switzerland are presented in Tables A3 and A4 in the online appendix.

In Switzerland, NCV rights efforts have been particularly successful in the French-speaking cantons. In contrast, the reforms have had difficulties passing parliamentary votes and popular referendums in German-speaking cantons (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Moret, Pomezny, Schlegel, Schwarz and Müller2016). Nevertheless, NCV rights are present in both German and French-speaking municipalities, see Figure A1 visualising the distribution of non-citizen enfranchisement across Switzerland. Two cantons, Jura and Neuchâtel, enfranchise non-citizens at the municipal and cantonal levels, whereas most other cantons transfer only municipal voting rights. Non-citizens have the right to vote in the municipal level polls in Jura (since 1979), Neuchâtel (2000), Vaud (2002), Geneva (2006) and Fribourg (2006), conditional on the duration of the residency. Likewise, the cantons of Appenzell-Ausserrhoden (1995) and Grisons (2004) have adopted legislation allowing municipalities to opt in to enable NCV rights for local elections.

While NCV rights are introduced in most cantons through referendums at the cantonal or, in a few cases, at the municipal-level to opt-in, the margins of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ votes for the passing of such legislation are often relatively narrow (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Moret, Pomezny, Schlegel, Schwarz and Müller2016). Thus, the distribution of NCV rights does not constitute an overwhelming systematic majority of support or rejection among the municipality’s electorate. Municipalities with NCV are not unique in having an otherwise positively skewed environment of attitudes towards non-citizens in the socio-political context. Therefore, our research design allows us to isolate the relationship between such policies and turnout among citizens – especially considering that the introductions of these enfranchisement policies are not motivated by boosting citizen turnout in the first place. Research shows that the introduction of NCV rights in the Swiss cantons are historically motivated by a perceived shared cantonal identity of citizen and non-citizen residents, non-citizens’ partaking in the functioning of the canton through the payment of taxes, the learning process from other cantons in the practice of non-citizens’ political rights, and previous traditions of granting political rights to foreigners such as in the case of Neuchâtel (Piccoli, Reference Piccoli2021). Hence, we argue that although the introduction of NCV rights simultaneously occurred with other constitutional changes, these additional constitutional amendments were unlikely to be linked to an increase in turnout; for further details, see pp. 7–8 in Appendix.

Eligibility conditions for such political rights also vary across cantons, see Table A3. While worthwhile to explore in future work, such eligibility differences are not the central variation of theoretical interest within the scope of this paper. Only Neuchâtel has exceptionally liberal rules of less than 5 years of residence condition, while most others require similarly strict rules between 5 to 10 years of residence in Switzerland. Table 1 below displays the number of municipalities granting voting rights to non-citizens in Switzerland. While in most cantons, all municipalities enfranchise non-citizens, there is also within canton variation in enfranchisement rules in some others. In Switzerland, voter registration and the distribution of voting material through the municipality occur automatically. Notably, the automatic registration of the voters in Switzerland applies the same across all cantons and municipalities.

Table 1 Number of Swiss municipalities with non-citizen voting (NCV) rights and share of the foreign population in 2018

Source: Swiss federal statistical office. Authors’ own calculations.

As of now, 599 municipalities in Switzerland out of 2205 have extended voting rights to non-citizen residents. According to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, in 2019, the total share of foreigners, that is, non-citizen residents, in Switzerland was about 25.3% (OFS, 2021b). Table 1 displays that, taken together, municipalities with NCV have a somewhat above average (33.6%) share of non-citizen residents. However, there is still quite a wide variation concerning the demographic heterogeneity across these municipalities. Rural cantons such as Jura have less than average foreign resident population sizes, whereas Geneva and Vaud (where the city of Lausanne is located) host non-citizen residents at rates well above the national average. Yet, many other urban areas with high ethnic heterogeneity, such as Zürich or Basel, do not extend political rights to non-citizens. In the Swiss case, we contend that residential ethnic heterogeneity alone cannot be a primary driver that determines local NCV rights reforms.

Studying the Swiss context is advantageous for several other reasons. First, Switzerland’s naturalisation policies are strict compared to other European countries, requiring at least 10 years of residency for standard naturalisations with costly application procedures and formal tests. Therefore, resident immigrants who have lived for a substantial period with normative claims to participation in local politics often may not have yet become eligible for regular naturalisation. Significantly, even facilitated naturalisation conditions, such as through marriage with a Swiss citizen or those born in Switzerland, are considerably difficult compared to other Western immigration countries, still requiring at least 5 years of residency and formal integration tests. Hence, such difficulties in citizenship law renders non-citizen enfranchisement politically consequential.

Second, the Swiss case is distinct from other European Union (EU) member states where EU migrants could gain municipal voting rights based on the Maastricht Treaty referring to EU citizenship. However, in Switzerland, such electoral rules are determined exclusively by Swiss law, which creates homogenous levels of inclusiveness amongst non-citizens regardless of whether they come from EU or non-EU countries. Swiss regulations are the sole law on NCV rights without specific preferential treatment agreements that may confound the relationship we are interested in. This makes Switzerland a particularly appropriate context to empirically isolate the implications of national enfranchisement reforms. Nevertheless, we argue that similarities in immigration history and the shared predominance of large immigration populations with other countries in Western Europe make the findings in this study useful for a larger set of advanced democracies.

Third, one potential challenge of studying the effect of non-citizen enfranchisement is whether citizens have an interest and knowledge on the topic. We argued that changes in political participation among citizens are reactive to the introduction of NCV rights. Citizens, therefore, at least need to be aware of such policy changes. In this respect, the Swiss context is particularly suitable because the issue is frequently vocalised at both cantonal and municipal levels. Based on Swiss direct democracy rules, expanding voting rights to non-citizens requires a constitutional amendment automatically subject to a popular vote. Between 1977 and 2014, citizens voted on 31 cantonal initiatives to introduce some electoral rights for non-citizens (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Moret, Pomezny, Schlegel, Schwarz and Müller2016). Moreover, the debates over introducing non-citizen enfranchisement are an ongoing political issue in Swiss municipalities. For instance, in January 2020, the cantonal parliament of Zürich adopted a preliminary initiative to allow its municipalities to introduce NCV rights if they wish so. Similarly, in Basel City, the parliament has adopted an initiative for a popular vote on NCV rights in 2020, which is expected to happen in the following 2 years. In September 2021, the canton of Solothurn rejected such an initiative to expand enfranchisement for the third time. In short, public debates and recurring attempts to introduce non-citizen enfranchisement combined with direct democracy imply that Swiss citizens are aware of the issue both before and right after the enfranchisement initiatives through the electoral mobilisation and registration campaigns organised by the civil society (especially trade unions), political parties, and certain municipalities themselves (Ferwerda, Reference Ferwerda2021).

Finally, in our SHP sample, the share of respondents with an immigration background and non-citizens are comparatively higher in municipalities with non-citizen enfranchisement in line with the official federal register statistics as in Table 1 (see Table A5). However, the presence or absence of NCV rights is an unlikely mitigator of an individual’s decision to choose their municipality of residence compared to economic and family reasons and past ties to existing immigration patterns (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Wanner, D’amato and Landös2018). Importantly, the larger share of immigrant populations in enfranchised municipalities can be explained mainly by their location near large urban areas around Geneva and Lausanne and distribution along with existing immigration networks and language proficiency. Moreover, the distribution of foreign residents across municipalities with or without non-citizen enfranchisement in Switzerland reveal no systematic differences due to the countries of origin, income, or education that can confound the impact of NCV rights on participation (Zufferey and Wanner, Reference Zufferey and Wanner2020), see pp. 9–11 in Appendix for further details. Most foreigners in Switzerland come from the neighbouring countries with France, Germany, and Italy, reporting the largest share of immigrant populations followed by Portuguese, Spanish, and Turkish immigrants due to the previous guest-worker programs.

Measurement of the dependent variable

To measure political participation, we use the following SHP item: ‘Let us suppose that there are 10 federal polls in a year. How many do you usually take part in?’ The answer options are on a continuous scale from 0 to 10. The question is repeated in every wave since 1999 except for 2006, 2010, 2012, and 2013. This formulation of turnout empirically fits our research interest. It does not refer to political choices but to participation rates in federal polls that are less conditioned and influenced by partisanship, making it a suitable formal participation measure. There are multiple federal polls every year, as opposed to federal legislative elections held only every 4 years, providing a better fit for evaluating our hypotheses in this longitudinal research design.

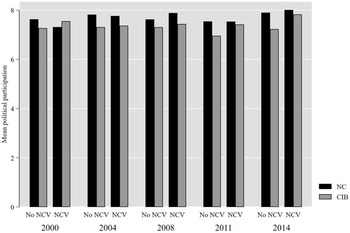

One limitation of this question is that it focuses on federal elections rather than the local or cantonal levels. This puts it at a different level than the enfranchisement laws we study here. Yet, there is no comparable question item specifically referring to sub-national level elections or polls in Switzerland. Nevertheless, in Switzerland, political interest at the local level is strongly correlated with the national level (Baglioni, Reference Baglioni, Zittel and Fuchs2007). Notably, federal and local polls in Switzerland are always held simultaneously, and ballots are distributed and collected jointly. Therefore, we sustain that the question adequately captures our interest in operationalising participation. In the appendix, pp.11–14, we further discuss our justification for this measurement strategy. Figure 1 visualises the average political participation in the two groups we study across our observation period at five time points.

Figure 1. Average reported poll participation by voter group by non-citizen voting (NCV) rights. Note: Authors’ own elaborations using Swiss Household Panel (SHP). NC: Native Citizens; CIB: Citizens with Immigration Background.

Figure 1 reveals that while differences in participation oscillate each year, overall, native citizens (NC) report, on average, higher participation – even though the discrepancies are modest in size. Next, on average, citizens with an immigration background (CIB) report higher participation in non-citizen enfranchised municipalities. Lastly, the average participation in our SHP sample is about seven out of ten polls. Compared to the actual participation rates in Swiss federal polls, this is higher, as the average participation rate in polls tends to be around 50% (OFS, 2021a). As in most surveys (Holbrook and Krosnick, Reference Holbrook and Krosnick2010), there seems to be an over-reporting of turnout in the SHP. Yet, neither empirically nor theoretically, there is reason to expect such over-reporting to vary systematically between non-citizen enfranchised municipalities and those without NCV rights (see Figure A5). Thus, such over-reporting of turnout is unlikely to have had a particular upward bias for citizens with an immigration background living in non-citizen enfranchised municipalities, see pp. 15–18 in Appendix for further discussion. More importantly, given our longitudinal research design, we can focus on not just between-individual differences in turnout but also on changes in reported turnout, further increasing our empirical leverage despite such over-reporting of participation levels.

Estimation strategy

In this study, we want to assess: (a) whether there are differences in turnout for citizens predicted by the presence or absence of NCV rights at the local level; and (b) whether the effect of such rules significantly heightens the political participation of citizens with an immigration background (CIB). The waves used in the study are 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, and 2014. The analysis is limited to the 2014 wave because of the data availability of the households’ residential location at the municipal level. We proceed with our analysis using two strategies to address our research questions, estimating both random effects (RE) and fixed-effects (FE) models. In our findings section, we begin by reporting the results of a series of linear RE models, estimating political participation differences between citizens based on non-citizen enfranchisement and group differences (NC vs. CIB) which contain both temporal and between-person variation. This allows us to focus on differences in participation levels based on native or immigrant background status rather than changes over time because we are also interested in reporting and evidencing the between-individual differences due to this largely time-invariant variable. Our RE models are specified with year fixed effects to account for time differences and the panel structure, and all of our models are estimated with individual clustered standard errors due to potential disturbances of heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation given our repeated observations data.

Considering estimation challenges in the influence of NCV rights on turnout, we further follow the empirical strategy outlined below, consisting of several steps of estimation and controlling for different possible confounders and alternative ways of modelling the data. First, we estimate two-way fixed-effects (2-way FE) models, accounting for between-individual differences and leaving only within-individual variation over time (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009: 165–167). RE models are less helpful to account for potential unobserved confounding at the individual level and to estimate the dynamic impact of AE on changing participation rates (Halaby, Reference Halaby2004). One crucial challenge of estimating the effect of NCV rights policy on citizen turnout is the time-invariant individual characteristics that correlate with the turnout. In this respect, the 2-way FE models with individual and year FEs allow us to remove all time-invariant attributes of an individual. In addition, controlling for alternative explanations of political participation, we specify all our main models with exogenous socio-economic and demographic variables (Cho, Reference Cho1999; Smets and van Ham, Reference Smets and Van Ham2013). See Table A1 for their descriptive summary and Table A2 for details of the question items we used for operationalisation.

Second, regarding potential time-variant individual-level characteristics, we further condition our estimations with alternative explanations of turnout based on socio-economic, civic, and political differences such as workforce status, union membership, religiosity, subjective placement on the left-right scale, political interest, and account for the country-of-origin differences for those citizens with an immigration background as established predictors of political participation (Strijbis, Reference Strijbis2014). We use SHP’s post-coded variable created using respondents’ answers to their country of origin categorized into 12 geographic regions. The different region clusters we consider are Northern, Eastern, Central, Western, South-West, Southern, and South-East Europe, Africa, Latin America, Northern America, Asia, and Oceania. Our substantive results are robust across different model specifications; see Tables A21 and A22 in Appendix.

Third, another issue is the time-invariant canton characteristics that predict a lower or higher likelihood of introducing NCV rights, demonstrated as the share percentage of the foreign-born population (predicts lower chances) and political partisanship. To account for these, we use canton fixed effects in our model estimations due to potential systematic differences between cantons, especially concerning political contexts and policies such as naturalisation laws. As robustness checks, we also explicitly model and study the political partisanship and share of foreigners in the municipality of residence. Notably, the presence of strong anti-immigration rhetoric and radical right-wing discourses are shown to suppress the minority vote (Simonsen, Reference Simonsen2020). Using data from the results of the legislative elections within our observation period (OFS, 2019a), we control for the share percentage of the vote for the dominant radical-right party in Switzerland (Swiss People’s Party SVP) in each municipality and report no change in our main findings, see Table A26. Moreover, we control for the size of the foreign population in each municipality (OFS, 2019b), and report no substantive change in our main results, see Table A27.

Finally, it could be possible that citizens with an immigration background, displaying systematically higher political interest and ambition choose to settle in municipalities with NCV rights because they signal better opportunities for participation and openness towards immigration. This would confound our estimations due to the residential selection of individuals who are more sensitive to democratic inclusiveness. First, no evidence suggests that foreign-born citizens with exceptionally high political interest self-select into municipalities with non-citizen enfranchisement. Most foreigners arriving in Switzerland report economic, professional, and family reasons for their move (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Wanner, D’amato and Landös2018). Regardless, we address such an issue with our models, estimating the relationships we study using both individual and canton fixed effects. Furthermore, to account for the possibility that citizens with an immigration background move to a non-citizen enfranchised context corresponding with their higher political participation, we replicate our analyses by removing all individual-year observations where an individual changes their municipality of residence from t − 1. Our results hold when considering only the respondents who remain in the same municipality (see Tables A24 and A25). Lastly, as a predictor of individuals for whom such engagement would be the most important, we add the overall political interest of respondents in our models and report no changes in our results (see Table A23).

Empirical findings

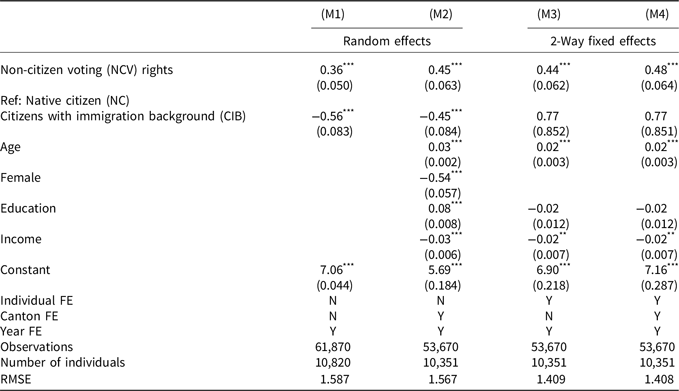

In Table 2, we present the results of two RE (M1–M2) and two FE (M3–M4) models estimating the direct effect of NCV rights on political participation. Model 1 presents our baseline model with just two variables: NCV rights and being a citizen with an immigration background (CIB) versus being a native citizen (NC) and year fixed effects. Model 2 adds socio-demographic covariates age, gender, education level, and income and canton fixed effects to the equation. The complete estimation results of the models are available in Table A14.

Table 2 Direct effects of non-citizen voting rights on political participation

Note: SHP waves 1999–2005, 2007–2009, 2011, and 2014 are used where the political participation question item was asked. Individual clustered robust standard errors in parentheses. The full table of results is available in the appendix (Table A14).

t P < 0.1. *P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

*** P < 0.001.

Across the board, the results from the RE models provide evidence for our hypothesis 1. On average, turnout is higher in municipalities with NCV rights, corroborating evidence that positively links electoral inclusiveness and political participation (Förster, Reference Förster2008; Stadlmair, Reference Stadlmair2020). In municipalities with NCV, citizens have reported as having participated in about 0.36 more polls than citizens in municipalities without NCV rights (see Model 1). As our dependent variable asks about participation in the last 10 polls, an increase in 0.36 polls can be translated into 3.6 percentage points higher participation in polls. When looking at our estimation removing between canton differences, all things considered, compared to the period before the introduction of NCV rights, citizens have reported as having participated in 0.45 more polls (or an increase of 4.5 percentage points participation in polls) when NCV rights are introduced (see Model 2). Next, Table 2 also reveals that CIBs report lower participation when compared with NCs, in line with earlier work (Jones-Correa, Reference Jones-Correa2001; Bird et al., Reference Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011; Simonsen, Reference Simonsen2020). Compared to NCs, CIBs report about 0.45 less federal poll participation (see Model 2), equivalent to about 4.5 percentage points fewer polls.

Next, to analyse how the adoption of NCV rights change political participation among citizens, we turn to our two-way fixed-effects models, removing all variation between individuals. Since Models 3 and 4 only use within-individual information, time-constant coefficients are dropped.Footnote 4 Looking at the last two models in Table 2, we find that when municipalities go from not having non-citizen enfranchisement to having such expansion of the demos, this increases the political participation among citizens living in such contexts. This effect holds when considering both participation differences between cantons (Model 3) and focusing solely on the variation of non-citizen enfranchisement rule changes within cantons and over time (Model 4). Looking at other covariates, that is, age, sex, education, and income, reveals that age and education are robust predictors of higher participation. In contrast, the opposite is the case for higher-income respondents. Overall, Table 2 confirms our hypothesis 1 and supports the argument that there is a link between giving non-citizens the right to vote that spills over to political participation dynamics among citizens (Filindra and Manatschal, Reference Filindra and Manatschal2020; Manatschal et al., Reference Manatschal, Wisthaler and Zuber2020).

Are citizens with an immigration background more sensitive to NCV rights?

Moving forward, we also suggested that the participation boosting effect of non-citizen enfranchisement would be particularly important for citizens with an immigration background (hypothesis 2). If this is true, we should see a statistically significant interaction term with a positive sign between being a citizen with an immigration background and living in a municipality with NCV compared to native citizens who live in such municipalities. To test this, we use the same stepwise modelling strategy as in Table 2, but this time add an interaction term between citizen groups and the NCV dummy variable, indicating such mitigating effects. Table 3 presents our RE and FE models; see Table A15 for the full table of results.

Table 3 Conditioning effect of non-citizen voting rights on political participation

Note: SHP waves 1999–2005, 2007–2009, 2011, and 2014 are used where the political participation question item was asked. Individual clustered robust standard errors in parentheses.

The full table of results is available in the appendix (Table A15).

t P < 0.1.

* P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

*** P < 0.001.

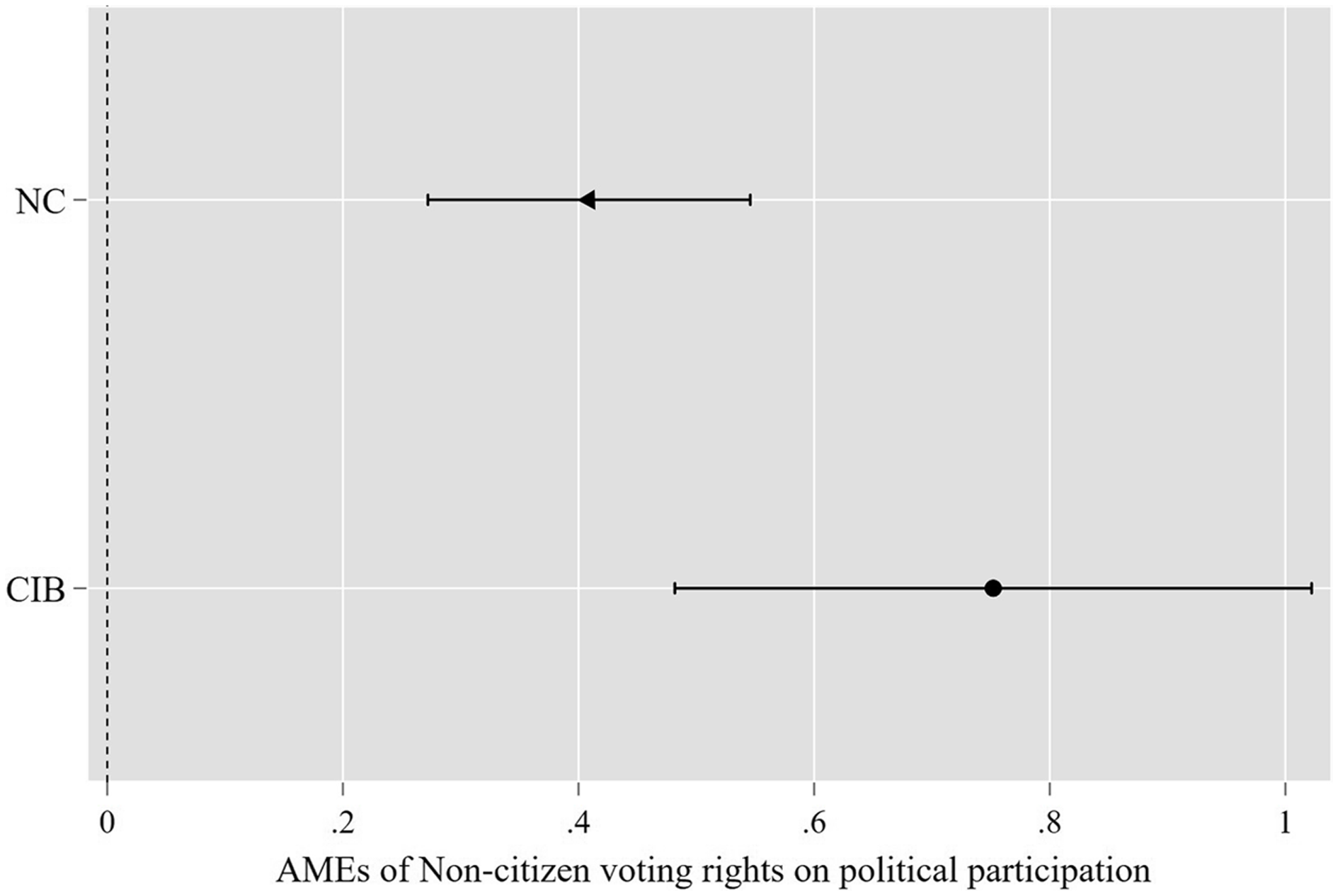

First, when looking at between-individual differences in RE models, citizen group status has a statistically significant (P < 0.05 level) interaction effect on the relationship between NCV and political participation (see Models 5–6). Table 3 reveals that for citizens with an immigration background, there is a stronger positive correlation with NCV and political participation when compared to native citizens. These findings are corroborated in the two-way fixed-effects models with (Model 7) or without between-canton variance (Model 8), removing all potential confounding due to individual and canton level differences. To visualise this interaction effect, we plot the average marginal effects (AMEs) of non-citizen enfranchisement on political participation across these two groups using Model 8 (see Figure 2). When looking at Figure 2, we see that compared to the period before the introduction of NCV, residing in contexts with electoral inclusiveness, on average, increases political participation by about 0.40 more federal polls for NCs and by about 0.75 more polls for CIBs. This translates into an increase in participation in polls of 4 percentage points for natives and 7.5 percentage points for citizens with immigration backgrounds.

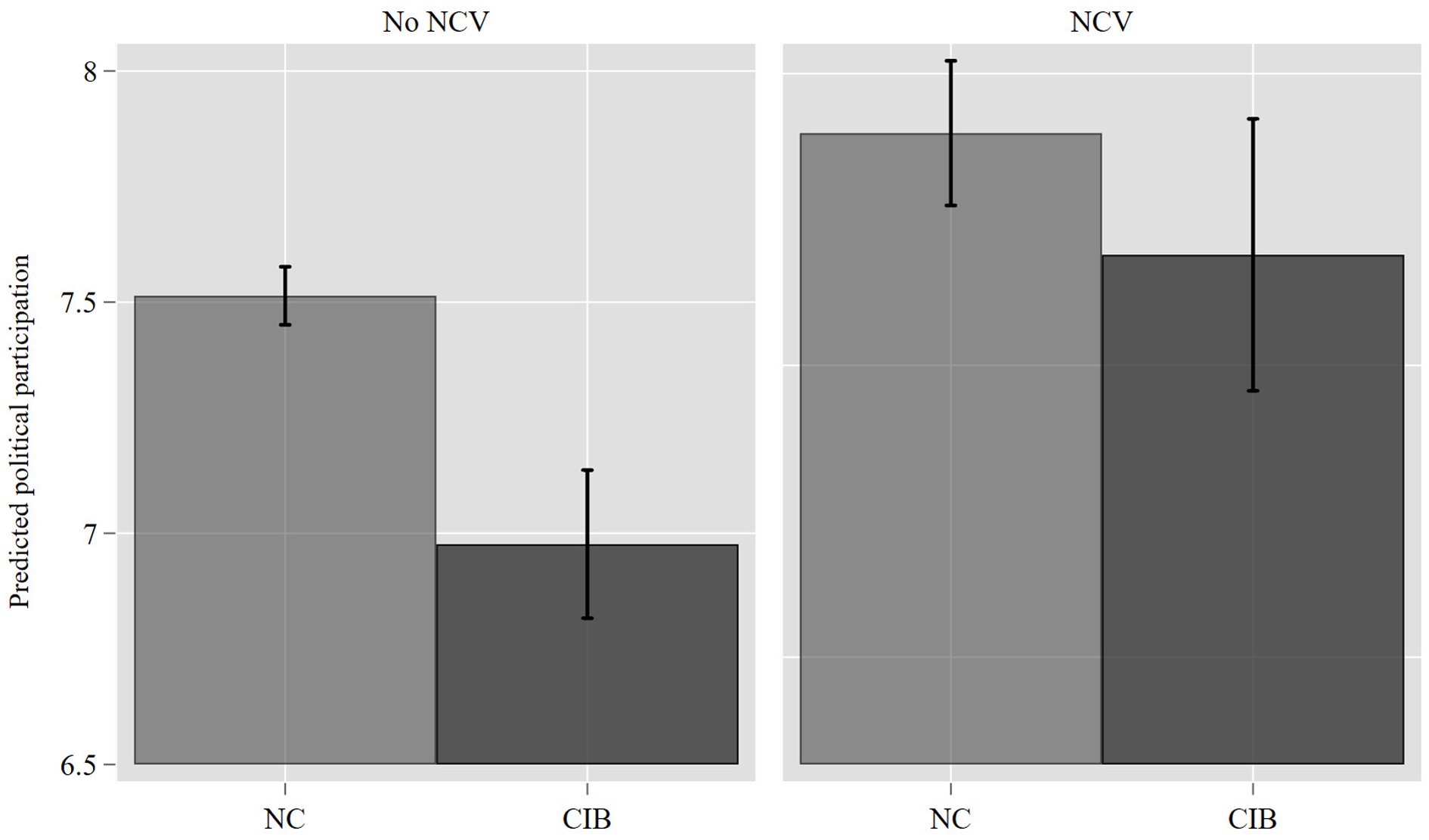

What do these differential effects imply more concretely for the turnout differences between these groups? To inspect this, we look at the predicted participation rates between NCs and CIBs using the RE model that show us the predicted participation differences between groups in municipalities before and after cantons introduced voting rights applied to all municipalities and the differences between municipalities where cantons allowed for opt-in rules (Model 6). Figure 3 demonstrates a statistically significant (at P < 0.05 level) gap of participation between NCs on the one hand and CIBs, on the other. The point estimate of the participation in non-enfranchised municipalities for NCs is about 7.51, whereas it is approximately 6.97 for CIBs. Yet, when looking at such differences in non-citizen enfranchised contexts, we see that the turnout gaps between these groups are narrower and are no longer predicted by immigrant background regarding the differences between NCs and CIBs. Figure 3 shows that the confidence intervals of the estimates for the two groups overlap in the contexts with NCV rights. Despite the overall higher turnout in non-citizen enfranchised contexts for both groups, on average, the participation boost enhances the participation of citizens with an immigration background (CIBs) in particular (compared with 6.97 to 7.69). In contrast, the differences are smaller among NCs (compared with 7.51 to 7.89). On the whole, our findings from Table 3 confirm our hypothesis 2 and support the argument that the positive effect of NCV on turnout is more substantial among citizens with an immigration background.

We check the robustness of our findings in several different ways. First, to narrow our investigation of the effect of NCV as an external policy intervention more precisely, we concentrate on the four cantons Neuchâtel, Vaud, Fribourg, and Geneva, which implemented NCV for all of their municipalities with a top to bottom approach. In this respect, following earlier research studying the impact of NCV on political and social policy outcomes, we hold that for the municipalities in each canton, these legislations can be plausibly characterised as an ‘exogenous temporal shock’ (Ferwerda, Reference Ferwerda2021: 328). Thus, using an alternative estimation method, we assign citizens with an immigration background after the introduction of the non-citizen enfranchisement in these cantons as the treated group and employ a logic of difference-in-differences estimation. We find that such an average treatment effect on the treated group (ATT) is about at least 0.31 corroborating our main results, see pp. 29–31 in the appendix for further details. Next, we also estimate a lagged dependent variable model as an alternative means to capture and evaluate the dynamic effects of NCV on our outcome variable, revealing substantively the same results, see Table A19. Finally, we address concerns about time-ordering and replicate our models with a 1-year lagged effect (t + 1) of NCV rights, relaxing the assumptions about when the municipalities should be considered as positive cases of NCV within our observation period, see Table A20, reporting that our results remain unchanged.

Underlying logics of the participation boost among citizens with immigration background in the context of non-citizen enfranchisement

Motivating our hypothesis 2, we suggested that NCV rights policies are more likely to be salient among citizens with an immigration background than native citizens. Yet, while our analyses found evidence for hypotheses 1 and 2, given data limitations and the scope of this paper, we have not been able to test changing dynamics of issue salience and the specific potential channels, that is, an electoral competition or democratic engagement, at the individual level which could be driving individuals’ reactions towards NCV rights differently. Indeed, as an electoral group, citizens with immigration backgrounds are more reactive, evidenced in our analysis. However, the competitive or more solidaristic logics that may underpin the observed electoral participation boost require a dedicated study of such mechanisms at the individual level. Nevertheless, we sustain that NCV rights might result in increased political participation of citizens with immigration backgrounds because their immigration experience renders such policies more important to them than natives.

While extant empirical work is divided between whether citizens with immigration backgrounds hold preferences in solidarity with new immigrants or whether they align more closely with native citizens (Strijbis and Polavieja, Reference Strijbis and Polavieja2018; Politi et al., Reference Politi, Chipeaux, Lorenzi-Cioldi and Staerklé2020; Manatschal et al., Reference Manatschal, Wisthaler and Zuber2020), when it comes to the increased political influence of non-citizen groups, there is considerable evidence pointing to the conclusion that the citizens with immigration backgrounds have less of a reason to hold grievances when it comes to non-citizen enfranchisement. Importantly, most evidence in the literature had looked at such preferences of the citizens with immigration backgrounds on sharing social rights with non-citizens (Kolbe and Crepaz, Reference Kolbe and Crepaz2016) and, even more so, towards their preferences on immigration policy (Strijbis and Polavieja, Reference Strijbis and Polavieja2018). Yet, recent comparative evidence shows that dual citizens, that is, those having a dual attachment with another country of origin, are more positive towards sharing political rights with non-citizens (Michel and Blatter, Reference Michel and Blatter2021). Here, using another dataset, that is, the Measurement and Observation of Social Attitudes in Switzerland (MOSAiCH) survey (Stähli et al., Reference Stähli, Joye, Sapin, Pollien, Ochsner, Nisple and Van Den Hende2015),Footnote 5 we also confirm that the finding reported by Michel and Blatter holds for the Swiss case. Our analysis suggests that naturalised immigrants, hence citizens with immigration backgrounds, are more supportive of introducing local NCV rights in Swiss municipalities than native citizens, see pp. 39–41 in Appendix.

From the perspective of the self-interest of CIBs, at the group level, the expansion of the so-called ‘immigrant vote block’ is shown to be mutually beneficial to both naturalised and non-naturalised immigrants in terms of representation (Bilodeau, Reference Bilodeau2009). Recent evidence in the Swiss case also clearly shows that political elites are more concerned with immigrant political representation in contexts of NCV rights and parties are more likely to strive for immigrant descriptive representation when non-citizen immigrants have local voting rights (Nadler, Reference Nadler2021). Furthermore, a peer-to-peer diffusion or the local contextual impact of increasing political knowledge socialisation and mobilisation is far more likely to be present among citizens with immigration backgrounds due to the NCV rights policies (Filindra and Manatschal, Reference Filindra and Manatschal2020; Bratsberg et al., Reference Bratsberg, Ferwerda, Finseraas and Kotsadam2021). Hence, at the group level, we contend that the observed boost of participation among citizens with immigration backgrounds is arguably less likely to be linked to a competition for political influence, which is more likely to be the case with native citizens. Overall, at the group level, there are more positive sentiments among the citizens with immigration backgrounds regarding how they view non-citizen enfranchisement.

Conclusion

This article examined the link between NCV rights and electoral participation, providing the first empirical evidence for the impact of immigrant-inclusive local electoral institutions on turnout. Our findings are politically meaningful not just because NCV rights are becoming an increasingly common and debated practice but also due to the consistent rise in ethnic heterogeneity in European demographic trends. The article makes several key contributions to our understanding of the politics of diverse advanced democracies.

First, we find that inclusive electoral rules beget comparable turnout rates reported by native voters and those with an immigration background. This emphasises the determining role of local electoral laws regarding overall turnout and, more specifically, for the political mobilisation of voters with immigration backgrounds echoing earlier studies (Jones-Correa, Reference Jones-Correa2001; Förster, Reference Förster2008; Gonzalez-Ferrer and Morales, Reference Gonzalez-Ferrer and Morales2013). Importantly, given the chronic challenge of low turnout in advanced democracies, our study proposes a potential remedy revealing that local contextual policy factors can be instrumental in boosting turnout and subsequently enhancing political incorporation in diverse democratic societies.

Next, our results point to the definitive need for more systematic research on the institutional and policy determinants at the local level regarding the political incorporation and engagement of citizens with immigration backgrounds. Much of the existing work has frequently emphasised the individual-level characteristics of underrepresented and under-mobilised groups to explain their political behaviour (Cho, Reference Cho1999; Wass et al., Reference Wass, Blais, Morin-Chassé and Weide2015). Yet, we find that local NCV rights matter when looking at voter participation and group-based turnout gaps between citizens. Adding to the growing evidence in recent research (Simonsen, Reference Simonsen2016; Simonsen, Reference Simonsen2020; Filindra and Manatschal, Reference Filindra and Manatschal2020), this study also casts doubt on the applicability of solely individual-based explanations of why citizens with immigration backgrounds are less mobilised electorally. Without going into normative debates concerning democratic legitimacy and who should be included in the demos (Blatter et al., Reference Blatter, Schmid and Blättler2017), our analysis of the Swiss case demonstrated that a policy, such as non-citizen enfranchisement, which targets non-citizen residents principally could indirectly generate certain positive externalities on other groups, especially those with immigration backgrounds, in line with earlier work. Our findings therefore relate to both the integration literature and political practice, in which naturalisation and enfranchisement are considered as alternative ways to boost political participation and integration.

The analyses also point to certain limitations in existing data and charts avenues for further research. Existing observational comparative data are limited for measuring citizens’ national identity and attitudes towards non-citizen enfranchisement, impeding our ability to account for the competing logics we proposed here. Therefore, we could not untangle which potential explanatory mechanism we speculated drives higher voter turnout in inclusive municipalities. While this paper aimed to evaluate the impact of NCV rights, future research should address which mechanisms at the individual level are more important in explaining such rises in turnout by collecting new data. Importantly, there may also be heterogeneities within the citizen groups based on countries of origin or other socio-cultural/socio-economic cleavages that could drive whether solidarity or competition may be at play and subsequent effect sizes, which we cannot untangle here considering data limitations and the sample sizes. This emerges as a fruitful research agenda to inspect the differences of participation drivers and predictors among the ‘immigrant voter’ block especially.

Lastly, our study cited evidence from Switzerland, which (for a large set of reasons) emerges as a uniquely fitting case to study the local non-citizen enfranchisement rules and their impact on citizens. Considering the context of Europe, while the Swiss case is particularly unique with its layered rules of sub-national variation, it is nevertheless comparable when it comes to engagement with immigration. Moreover, the proposed theoretical framework on the competition and the democratic engagement mechanisms in context with NCV rights are applicable outside Switzerland. Notably, our results are relevant for other diverse European societies with a wide variation within citizen groups regarding immigration backgrounds. For instance, future research can investigate whether, in countries with nationwide NCV rights rules, such as in Northern Europe, citizens with an immigration background report relatively higher political mobilisation and integration when compared to those with similar socio-demographic profiles living in countries without NCV rights. Likewise, studies can also further leverage the temporal changes in more contemporary enfranchisement reforms, such as in the Netherlands and Belgium, to study the political consequences of NCV rights policies in different contexts and across distinct electoral groups.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000029.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the American Political Science Association’s Annual Meeting (2020) and the Swiss Political Science Association’s Annual Congress in Lucerne (2020), as well as in seminars and workshops in Geneva and Malmö. We would like to thank all the participants and discussants for their helpful feedback. We are especially thankful to Willem Maas, Elaine Denny, Simon Hug, Lucas Leeman, Jonas Pontusson, Alireza Behtoui, Phillip Lutz, Adrien Petitpas, Andri Meier, and Davy-Kim Lascombes for their comments and suggestions for this paper and their encouragements.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.