Introduction

Demand for right-wing populism (RWP) in European societies has traditionally been traced back to globalization and economic insecurity (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Oesch, Reference Oesch2008), cultural change in society (Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), and more recently, to voter discontent (Elchardus and Spruyt, Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Capelos and Katsanidou, Reference Capelos and Katsanidou2018; Mutz, Reference Mutz2018; Lammers and Baldwin, Reference Lammers and Baldwin2020), and emotions (Magni, Reference Magni2017; Rico et al., Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017; Salmela and Von Scheve, Reference Salmela and Von Scheve2017). In this study, we build on populism research in discontent and emotions and introduce (low) subjective well-being (SWB) as an overlooked, potential individual-level correlate of populist, and nativist sentiment. Discontent in populism research has been conceptualized as group-level deprivation, societal pessimism, collective nostalgia, or status anxiety, while the broader notion of self-centered discontent, that is, life dissatisfaction, has received very little attention. This is a remarkable gap in the literature since people may not be able to identify the exact reason why they are dissatisfied or not feeling well. Instead, they simply consult their state of overall well-being for cues when forming their political attitudes and preferences. In addition to domain-specific discontent, it is plausible that how we generally feel about ourselves and our lives affects how we think politically.

SWB and self-rated health have been linked to political participation (Weitz-Shapiro and Winters, Reference Weitz-Shapiro and Winters2011; Liberini et al., Reference Liberini, Redoano and Proto2017; Rapeli et al., Reference Rapeli, Mattila and Papageorgiou2020) and electoral behavior (Bernardi, Reference Bernardi2021; Kavanagh et al., Reference Kavanagh, Menon and Heinze2021). Citizens with high life satisfaction are more likely to support political incumbents and be satisfied with the functioning of democracy (Di Tella and MacCulloch, Reference Di Tella and MacCulloch2005; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2020), while life dissatisfaction relates to lower political trust, democratic dissatisfaction and negative views on out-groups in society (McLaren, Reference McLaren2003; Zmerli and Newton, Reference Zmerli and Newton2007). Meanwhile, the influence of SWB on nativist attitudes (i.e. supporting the interests of native inhabitants of a country against foreign influence), and populist attitudes is a promising field for further research. Apart from some evidence that low SWB influences RWP vote choice (Herrin et al., Reference Herrin, Witters, Roy, Riley, Liu and Krumholz2018; Nowakowski, Reference Nowakowski2021; Ward et al., Reference Ward, De Neve, Ungar and Eichstaedt2021), we know little about how it interrelates with voters’ populist and nativist attitudes. This is a significant gap in the literature, considering the exceptional success of RWP parties in the European political landscape in the past decades, a phenomenon which goes hand in hand with increased populist and nativist sentiment among a part of the electorate (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012; Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel, Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018).

In emotion theory, negative affective experiences, such as anger, fear, sadness or anxiety have been positively linked to populism (Magni, Reference Magni2017; Rico et al., Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017; Salmela and Von Scheve, Reference Salmela and Von Scheve2017), and anti-immigration sentiment (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Erisen et al., Reference Erisen, Vasilopoulou and Kentmen-Cin2020). Negative emotions are likely more frequent among individuals with low well-being, yet emotions are transient (Ward et al., Reference Ward, De Neve, Ungar and Eichstaedt2021), while low SWB is a mental state that stays relatively stable at least in the medium-term, notably when measured as life satisfaction (Diener, Reference Diener2000). It is therefore worth examining the emergence of populist and nativist attitudes through the lens of SWB and not only through single emotions that people experience occasionally.

SWB also provides more insight to people’s well-being than what objective indicators alone can achieve. Objective indicators such as personal and country wealth (Diener and Biswas-Diener, Reference Diener and Biswas-Diener2002), good governance (Frey and Stutzer, Reference Frey and Stutzer2002), and personal circumstances such as being healthy, married (Diener, Reference Diener2000) and having dense social networks (Helliwell and Putnam, Reference Helliwell and Putnam2004), have been linked to SWB. However, due to the fundamental nature of SWB, the subjectivity emerges from the experience itself, and not from the how it is reported. Objective conditions can certainly contribute to a feeling of being well, but they should not be equalized with the experience of being well (Rojas, Reference Rojas2017).

The purpose of this study is to clarify how SWB relates to populist and nativist attitudes. We use the Finnish 2019 National Election Study (FNES), a cross-sectional survey on the political attitudes and behavior of Finnish citizens. The FNES contains information on the electorate’s life satisfaction as well as a broad battery of items measuring populist and nativist attitudes, allowing us to examine how these interconnect. We demonstrate that low SWB is positively associated with populist and, to a certain degree, also nativist attitudes, irrespective of many forms of economic discontent. Additionally, we find that SWB is distinct from many other well-known correlates of populism, such as democratic dissatisfaction, political efficacy or generalized trust. Since we use observational data, we are limited to testing for associations in the relationships between SWB and populist and nativist attitudes. The results should not be read as causal proof, but as an investigation of whether populist and nativist citizens score lower on SWB. The findings suggest that voter well-being is intimately linked with populist sentiment, and to a certain degree, also with nativist sentiment. SWB provides a useful and holistic psychological framework to examine the resonance of RWP in today’s Western European democracies. Clearly, populist and nativist attitudes are at least partly a reflection of a citizen’s low SWB, even in Finland, with comparatively high levels of economic and social well-being, widespread social security and overall life satisfaction.

Theoretical Foundations

Defining populist and nativist attitudes

Populist and nativist attitudes are conceptually distinct and should be studied as such. People can score high on one set of attitudes and low on the other, which is why they will be analytically distinguished. A recent experiment showed that nativist views possibly reinforce populist attitudes, but not vice versa, which the authors believe is because ‘nativism is more likely than populism to be a source of deeply meaningful collective identity’ (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Bonikowski and Parlevliet2021: 258).

Traditionally, research on the demand-side of populism has been eclipsed by a focus on populist supply, although investigating citizens’ populist attitudes has become an increasingly popular research agenda (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012; Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Elchardus and Spruyt, Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel, Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018). Rather than a full-fledged ideology, populism is an idea or political style, in the sense of an “oppositional moral framework, which allows for a forceful critique of particular social groups” (Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2017: 185). The much-cited ideational approach (Mudde, Reference Mudde2017; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2018) identifies two minimum conditions of populism: an antagonism between the ‘pure people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’, typically the political elite, and the call for popular sovereignty (people centrism) in politics.Footnote 1 The people-centrism in populism is anti-pluralist (especially in RWP), meaning that it opposes the use of compromise in politics and calls for the implementation of majority will (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012). We therefore consider antielitism and antipluralism as core components of populist attitudes which must both be shared if individuals are to be considered populist.

In addition to populism, RWP is characterized by nativism. Nativism defines the populist ‘virtuous people’ in terms of a culturally, ethnically and religiously homogeneous people and nation, and argues that non-native elements, brought in by immigration and multiculturalism, are threatening to the nation-state (Higham, Reference Higham2002; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). Nativism shares the populist view of an opposition between ‘us’ and ‘them’, the in-group and the out-group (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Bonikowski and Parlevliet2021). Immigrants, as well as cultural, ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, are typically the targeted out-groups. Out-group exclusion goes hand in hand with in-group preference. In-group favoritism is related to Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) in the way it uses bias towards the in-group to perpetuate group hierarchies (Levin et al., Reference Levin, Federico, Sidanius and Rabinowitz2002). Thus, in-group members are assumed trustworthy and virtuous, while out-group members are deemed ‘unfriendly’ and ‘untrustworthy’ (Kinder and Kam, Reference Kinder and Kam2010). In-group membership in the nativist perspective ‘can be inclusive as long as new members accept the nation’s political creed’ (Guia, Reference Guia2016: 5). Thus, foreigners who adopt the host country´s customs and traditions and respect their law and institutions could be embraced as part of the in-group (in contrast to ethno-nationalism) (Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2017).

Discontent in populism research

In the psychology of populism, negative emotions such as fear, anger, and anxiety (Rico et al., Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017; Capelos and Demertzis, Reference Capelos and Demertzis2018; Marcus, Reference Marcus2021), personality factors (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Rooduijn and Schumacher2016; Fatke, Reference Fatke2019), or importantly for this study, discontent (Elchardus and Spruyt, Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Capelos and Katsanidou, Reference Capelos and Katsanidou2018; van der Bles et al., Reference van der Bles, Postmes, LeKander-Kanis and Otjes2018; Lammers and Baldwin, Reference Lammers and Baldwin2020; Giebler et al., Reference Giebler, Hirsch, Schürmann and Veit2021), have been identified as explanatory frameworks. Nevertheless, previous research has been somewhat ambiguous about the exact nature of the discontent that feeds populism (Giebler et al., Reference Giebler, Hirsch, Schürmann and Veit2021). It has mainly been understood as society-centered discontent, relating to group-level deprivation, societal pessimism and perceptions of crises, collective nostalgia, or related sentiments (Elchardus and Spruyt, Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Capelos and Katsanidou, Reference Capelos and Katsanidou2018; Lammers and Baldwin, Reference Lammers and Baldwin2020). Whenever self-centered discontent has been considered, it has typically been reduced to domain-specific concerns, such as status anxiety or social marginalization (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Mutz, Reference Mutz2018) that essentially express the respect or esteem people believe they are accorded within the social order. Yet, discontent might not only be group- or society-centered, or domain-specific. A general and diffuse dissatisfaction with life as a whole, or low SWB, can also explain why voters develop populist and nativist attitudes.

Low SWB as self-centered discontent

The well-being framework allows us to develop an encompassing conceptualization of self-centered dissatisfaction, by contrast to domain-specific grievances. The political relevance of SWB is increasingly recognized as it has been associated with electoral turnout (Flavin and Keane, Reference Flavin and Keane2012; Liberini et al., Reference Liberini, Redoano and Proto2017), conservative vote choice (Napier and Jost, Reference Napier and Jost2008) and satisfaction with political institutions (Zmerli and Newton, Reference Zmerli and Newton2007; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2020). Conversely, low SWB depresses turnout (Ojeda, Reference Ojeda2015), increases protest intentions (Lindholm, Reference Lindholm2020) and decreases support for center-right parties (Bernardi, Reference Bernardi2021).

Status anxiety and social marginalization are likely correlated with life dissatisfaction. Yet life satisfaction is conceptually a broader construct that taps on the global evaluation people make about the good and the bad in their lives. It is drawn from an assessment of the current actual self but also representations about the past self and expectations about the future possible selves, whether positive or negative (Sani, Reference Sani2010). Similarly, ressentiment and the resulting feelings of anger and hatred have been identified as emotional defense mechanisms among those who perceive themselves in a powerless, precarious, and deprivileged situation (Salmela and Capelos, Reference Salmela and Capelos2021). Although ressentiment also expresses a diffuse feeling of dissatisfaction, it unavoidably draws from social comparison, while SWB is an assessment individuals make primarily by consulting their subjective standards and expectations.

Past studies have compared self- and society-centered discontent in relation to populism, yet arguably with some weaknesses. Van der Bles et al. (Reference van der Bles, Postmes, LeKander-Kanis and Otjes2018) concluded that dissatisfaction over the shape of society is more influential than discontent that is oriented towards the self. However, they measured self-centered dissatisfaction by personal experiences with specific negatively perceived societal problems, not by actual life dissatisfaction. The authors’ definition of self-centered discontent is highly specific and thus not a good proxy for low SWB; individuals can feel dissatisfied with life whether or not they are personally affected by the societal events they perceive negatively. Similar concerns can be raised about a study conducted in Belgian Flanders (Elchardus and Spruyt, Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016). While the authors concluded that societal discontent rather than life dissatisfaction drives populist attitudes and preferences, they measured life dissatisfaction with feelings of anomie or relative deprivation. This is potentially problematic, because anomie, relative deprivation, and life dissatisfaction are conceptually distinct constructs (Blanco and Diaz, Reference Blanco and Diaz2007; D’Ambrosio and Frick, Reference D’Ambrosio and Frick2007). Certainly, there is recursiveness, as people dissatisfied with their lives may perceive themselves as being unjustly deprived, which, in turn, may erode life satisfaction. Despite their partial conceptual overlap, the main difference in relative deprivation and life dissatisfaction stems from the source of these feelings; while relative deprivation is an assessment of one’s social position and draws directly from social comparison, people evaluate their life satisfaction based on the subjective standard of the (past, present, future) self (Sani, Reference Sani2010). Simply put, while relative deprivation captures grievances related to one’s social position, life dissatisfaction captures grievances related to one’s quality of life. Since the relevant benchmark for life dissatisfaction and relative deprivation are different, both deserve attention when exploring the attitudinal correlates of RWP.

Finally, Giebler et al. (Reference Giebler, Hirsch, Schürmann and Veit2021) found that societal, but not self-related, discontent fosters the propensity to vote for the German RWP party. But party choice is also driven by other factors than attitudes (such as strategic voting (Myatt, Reference Myatt2007)), creating the need to examine how self-centered discontent relates to attitudes. In contrast to the strongly domain-specific focus of research in the psychology of RWP, we extend this literature and focus on the broader assessment of one’s life as a potentially crucial psychological pathway (Ward et al., Reference Ward, De Neve, Ungar and Eichstaedt2021) to the adoption of populist and nativist attitudes.

Linking low SWB to populist and nativist attitudes

In addition to providing new insight into voter discontent, low SWB provides its own explanatory framework for populist and nativist attitude formation. Firstly, in line with retrospective theories of voting (Healy and Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2013), life satisfaction becomes a utility that voters consult when deciding whether or not to support political incumbents and institutions (Liberini et al., Reference Liberini, Redoano and Proto2017; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2020). Satisfied persons tend to interpret the status quo in politics as desirable, while life dissatisfaction is a cue for demanding change. Since populism calls for popular sovereignty and the rejection of several core aspects of Western liberal democracy (such as seeking compromise and ensuring minority rights), it likely resonates well among citizens with low SWB who seek a change. Secondly, and following affective intelligence theory, negative states and feelings make people more open to changing their political predispositions (Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Hutchings, Banks and Davis2008; Brader, Reference Brader2011). Life dissatisfaction belongs to those states that persons draw on to evaluate their political preferences. SWB becomes the basis for a ‘happiness contract’ that citizens make with incumbents and the political system (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2020). They use heuristics to assess their current wellbeing and adjust their level of political support accordingly, by rewarding the political establishment for increases in SWB and punishing it when SWB decreases (Tiedens and Linton, Reference Tiedens and Linton2001; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2020).Footnote 2

Thirdly, low SWB provides fertile ground for in-/out-group thinking. In social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel and Turner1979), not feeling well about oneself is positively associated with high in-group esteem or ‘collective narcissism’ (Golec de Zavala et al., Reference Golec de Zavala, Federico, Sedikides, Guerra, Lantos, Mroziński, Cypryańska and Baran2020: 741), explaining why low SWB would motivate people to draw sharp boundaries between their in-group and the out-groups in society, whether the out-groups are political elites (as in populism) or immigrants and other minorities (as in nativism). Dissatisfied individuals have a heightened tendency to blame their unhappiness on the out-group(s), seeing them as a threat to the economic prosperity and cultural dominance of their in-group (McLaren, Reference McLaren2003; Ward et al., Reference Ward, De Neve, Ungar and Eichstaedt2021), while participation in the positively valued in-group becomes a strategy to raise self-esteem, positive emotionality and, by extension, overall life satisfaction, even during hardship (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2001; Golec de Zavala et al., Reference Golec de Zavala, Federico, Sedikides, Guerra, Lantos, Mroziński, Cypryańska and Baran2020).Footnote 3 From a nativist perspective, nationality or ancestry are attractive group identities that are less subject to competition, have a homogeneous identity, and an exclusionary logic (McLaren, Reference McLaren2003; Kemeny et al., Reference Kemeny, Gruenewald and Dickerson2004). From a populist perspective, political elites constitute out-groups that threaten the in-group of individuals suffering from low SWB. Political elites are seen as undermining the interests of the ‘hard-working’ ordinary people that are positively appraised by populist citizens.

Through this lens, we can understand the attraction of populism and nativism among people with low SWB. Opposition to immigration, hostility toward political elites, and in-group favoritism are ways to strengthen in-group identity and cope with low SWB. Early studies on SWB and RWP indicate that well-being indeed correlates with RWP voting. Ward et al. (Reference Ward, De Neve, Ungar and Eichstaedt2021) showed that life dissatisfaction related to increased odds of a Trump vote in the 2016 USA elections. Herrin et al. (Reference Herrin, Witters, Roy, Riley, Liu and Krumholz2018) examined the electoral shift towards Trump through aggregate SWB and showed that change was greatest in areas with lowest SWB as well as the greatest drop in SWB prior to elections. Beyond the USA, Nowakowski (Reference Nowakowski2021) showed that life dissatisfaction, and not merely political dissatisfaction, links to a RWP vote across Europe, while Lindholm et al. (forthcoming) associate SWB with RWP voting in Europe through political distrust and anti-immigration sentiment. Focusing on attitudes instead of vote choice, we expect that low SWB, measured by life dissatisfaction, correlates positively with populist attitudes (Hypothesis 1) and nativist attitudes (Hypothesis 2).

Populism, nativism and well-being in Finland

Populism and nativism have flourished in European politics during the last decade, including in Finland, where the RWP party, the Finns (Perussuomalaiset), most prominently advocates these ideas. In the 2019 parliamentary elections, the Finns won nearly 18 % of votes becoming the second largest party (Ministry of Justice, 2022). The Finns party supporters have since 2015 clearly shifted to the right in their self-identification (Isotalo et al., Reference Isotalo, Söderlund and von Schoultz2020). Moreover, the growth of demand-side RWP has been accompanied by a moderate, yet noticeable, polarization, as the previously dominant center-position of the electorate has slightly given way to increased self-identification on both sides of the economic and sociocultural left-right scales (Isotalo et al., Reference Isotalo, Söderlund and von Schoultz2020). With the recent flourishing of populist and nativist ideas and the polarization of public opinion, the Finnish context provides a fairly representative setting for studying the dynamics of populist and nativist attitudes in Western Europe. Regarding SWB, Finland tops international rankings of aggregate life satisfaction (Helliwell et al., Reference Helliwell, Layard, Sachs and De Neve2020), which has notably been explained by high economic and social well-being, widespread social security and well-functioning democratic institutions. However, since life satisfaction is drawn from an inherently personal standard, variation in life satisfaction obviously exists, even in the Finnish context.

Data and methods

The data

The 2019 FNES is a nationally representative post-electoral survey conducted in conjunction with the Finnish parliamentary elections. The survey was conducted through face-to-face interviews and an additional self-administered questionnaire. The sample consists of about 1600 respondents with the right to vote in national elections, of which about 47% completed the drop-off questionnaire (Grönlund and Borg, Reference Grönlund and Borg2020). Since life satisfaction was asked in the drop-off questionnaire, the sample size was reduced to 753 respondents. The analyses were weighted with regard to the mother tongue, age, and gender.

The measures and method

The dependent variables are measured on Likert scales. All items were coded so that higher values express stronger populist or nativist attitudes. An advantage of studying attitudes instead of behavior (vote choice) is that it allows us to include non-voters in the sample. This is especially important when studying populism, since nonvoters are likely to share many of the populist attitudes (Giebler et al., Reference Giebler, Hirsch, Schürmann and Veit2021).

The populist and nativist items are part of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) module of the FNES. The CSES scales have been found to have a fairly good fit and high external validity (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). The scales have also been criticized, notably for their low conceptual breadth (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020) and for possibly confounding elements of some varieties of populism (authoritarian populism, left populism) with the core dimensions of populism (Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen2020). Yet, having a strong leader responds to the populist desire to introduce a direct link between the people and the rulers (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2014). Likewise, the belief that politicians only care about the rich and powerful is not only a trait of left populism, it also reflects the anti-elitist view that politicians do not serve the interests of the ordinary people (Quinlan and Tinney, Reference Quinlan and Tinney2019). Exploratory factor analyses (EFA, see online Appendix A3) indicate that the corresponding itemsFootnote 4 load well on the populism construct in the FNES. We therefore analytically consider both items to measure populist attitudes. Nativist attitudes (‘out-group attitudes’ in the CSES) are measured through seven items expressing immigration perceptions (crime, economy, culture) and perceptions about being a true national. These items capture both anti-immigrant prejudice and in-group favoritism based on national and cultural ancestry. One CSES item on nativism is not available in the FNES data (‘It is better for society if minorities maintain their distinct customs and traditions’).

The distribution of the populism and nativism items are available in online Appendix A1. Despite the many advantages of surveys, a drawback is their potential vulnerability to response bias. However, the distributions of the dependent variables do not indicate any serious bias toward intermediate or extreme responses. The amount of non-response stays low at less than 5,5 % for all items.

The independent variables and their distributions are available in Appendix A2. We use life satisfaction as an overarching measure of SWB. It is an evaluation people make by balancing positive and negative evaluations about their lives. Consequently, it captures an overall assessment of quality of life, instead of domain-specific aspects, and allows individuals to evaluate their satisfaction against a subjective standard, drawn from personal feelings, opinions and perceptions, instead of an externally imposed standard (Diener, Reference Diener2012). Life satisfaction has high consistency and temporal reliability (Diener, Reference Diener2000). The four-point scale was reversed for the analyses, making higher values express stronger dissatisfaction. Despite its advantages, a single-item measure cannot reveal which SWB dimension(s) are particularly relevant for populist and nativist attitudes. To our knowledge, there are currently no comparative surveys that include both a broad selection of populist and nativist attitudes and multi-dimensional measures of SWB (that are distinct from domain-specific dissatisfaction, relative deprivation, or related measures). Despite this drawback, we believe that there is merit in examining people’s populist and nativist sentiment from the rather novel SWB framework, albeit through an overarching item of life satisfaction. Like the single-item measure of self-rated health, which is a commonly used indicator of a person’s health status, life satisfaction involves making a broad evaluation that encompasses many different aspects that individuals relate to a good life. In the absence of more nuanced measures in the data, our analysis relies on previous scholarship (e.g. Diener et al., Reference Diener, Inglehart and Tay2013; Jylhä, Reference Jylhä2009) that portrays single-item measures of wellbeing/health as robust indicators of the underlying concepts they are measuring.

In general, reported life satisfaction is high in the sample, with about 90 % being fairly or very satisfied. It reflects the conclusions of studies that identify Finland among the ‘happiest nations’ in the world. High life satisfaction is not uncommon in survey data due to the influence of social desirability and self-selection (Diener, Reference Diener1994; Cummins, Reference Cummins2003), although self-administration (used in the FNES) attenuates socially desirable response bias (Nederhof, Reference Nederhof1985). However, it shall be kept in mind that the few cases in the most dissatisfied categories entail that most variation in the data can be found between very satisfied and fairly satisfied respondents.

We control for the influence of conventional sociodemographic predictors (gender, age, education), economic concerns, generalized trust, left-right self-placement, internal and external political efficacy, and satisfaction with democracy. Including economic concerns allows us to demonstrate that life dissatisfaction is distinct from unhappiness with pecuniary aspects of life and evaluate how life dissatisfaction performs compared to society-centered economic discontent. Generalized trust, democratic satisfaction, and external efficacy correlate with high life satisfaction and low RWP support (Helliwell and Putnam, Reference Helliwell and Putnam2004; Zmerli and Newton, Reference Zmerli and Newton2007; Flavin and Keane, Reference Flavin and Keane2012; Berning and Ziller, Reference Berning and Ziller2017), while internal efficacy may even strengthen populist attitudes (Rico et al., Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2020). Left-right self-identification is considered to avoid confounding the results from relationships that make left-leaning individuals more skeptical of elites and right-leaning individuals to hold more conservative views on the nation and nationality (Rico et al., Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017).

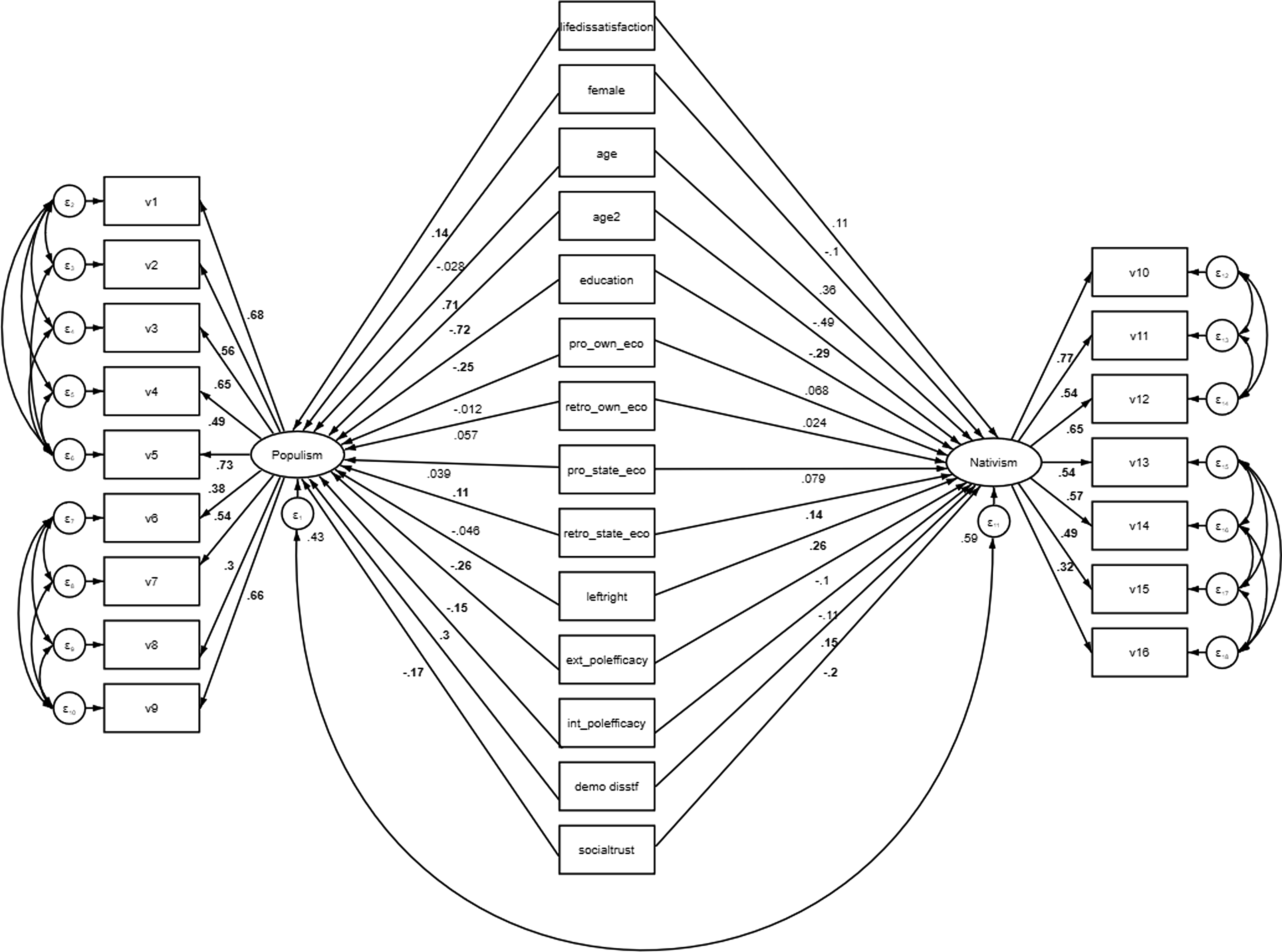

Populist and nativist attitudes are examined with structural equation modelling (SEM). An advantage of SEM over traditional regression modelling is that it allows estimation of structural and measurement models with latent variables in a single model, thus estimating a series of relationships simultaneously. Additionally, SEM corrects for measurement error, leading to a more accurate representation of constructs and relationships between constructs. Prior to full SEM, factor analyses were conducted to ensure that the populism and nativism items load on the expected clusters of attitudes. Figure 1 reports the results of the main SEM analyses.

Figure 1. SEM main parameters, model 4.

Notes: FNES 2019 data. Coefficients are standardized. Significant (p < 0.05) results are in bold. For full variable names and covariance parameters, see A6.

Results

Factor analyses

We expect antielitist and antipluralist attitudes to load on populism, and anti-immigration attitudes and in-group favoritism to load on nativism. EFA (Appendix A3) revealed that each of the main attitude clusters – populism and nativism – has two sub-dimensions: antielitism and antipluralism load on populism, while anti-immigration sentiment and in-group favoritism load on nativism. Since populism is a noncompensatory attitudinal syndrome (Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen2020), we consider both subsets of attitudes to be necessary for populist or, respectively, nativist attitudes to be activated. However, populist and nativist attitude clusters are analytically separated, since voters can score high on one and low in the other attitude (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Bonikowski and Parlevliet2021).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), where populist and nativist attitudes and their measurements were mutually orthogonal, conveyed a bad overall fit (SRMR = 0.17, CD = 0.98, CFI = 0.78, TLI = 0.74, RMSEA = 0.107 (0.103/0.112)). Allowing covariance between the attitudes is conceptually plausible and improved the CFA model fit significantly. The results of the final CFA solution are found in Appendix 4. The antielitism and antipluralism items (v1–v9) identified in the EFA load on populism, whereas anti-immigration attitudes and in-group favoritism (v10–v16) load on nativism. Both attitude clusters have high reliability (CR = 0.80 for populism; CR = 0.76 for nativism). The factor analyses suggest that the data reflect fairly well our conceptualization of populist and nativist attitudes.

Bivariate relationship

Table 1 and Figures 5a, 5b (Appendix A5) illustrate the bivariate association between SWB and the attitudes. Since factor scores retrieved from the CFA are not in a natural scale, we instead use composite indices (0–1) of the items for each cluster for convenient interpretation. The reliability of the composite indices is satisfactory (see Table 1). The indices are Goertz-corrected, meaning that the overall attitude scores are defined by the lowest value of their sub-dimensions (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006). This avoids a situation where respondents score high on populism or nativism without adhering to both of their subdimensions.

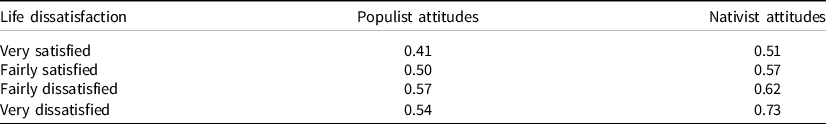

Table 1. Mean populist and nativist attitude intensity, by life dissatisfaction

Data: FNES 2019. Attitudes are composite indices (Goertz corrected) rescaled from 0 (lowest) to 1 (highest). Cronbach’s α: populism = 81; nativism = 0.82. Average inter-item correlations: 0.29 to 0.43.

The mean scores of populist and nativist attitudes by level of life dissatisfaction (Table 1) illustrate how the intensity of populist and nativist attitudes rises as life dissatisfaction increases. The increase in attitude-intensity between highest to lowest life dissatisfaction is the strongest for populism at 0.22, although the mean populism score slightly decreases between the fairly and most dissatisfied category. Rather than a substantial effect, we suspect that it is an effect due to the low prevalence (2 %) of very dissatisfied respondents in the data.

Figures 5a, 5b (see A5) show the relative distribution of populist and nativist attitudes (as 0–1 Goertz-corrected indices) by life dissatisfaction. The attitudes are categorized from low to high intensity for convenient interpretation. Figures 5a, 5b illustrate how the intensity of populist and nativist attitudes follow the level of SWB among the Finnish electorate. The vast majority of the less than very satisfied respondents score medium-high (>0.5) or high (>0.75) on nativist attitudes. Among the two dissatisfied groups, 37–40 % score high on nativism, while the corresponding percentages are only 13% and 7%, respectively, among the fairly and most satisfied respondents. The differences are less pronounced for populist attitudes. While low or fairly low populism scores are distributed across all levels of life satisfaction, high populism scores (>0.75) are clearly more widespread among fairly dissatisfied (27 %) and very dissatisfied (11%) respondents. Conversely, the vast majority of very satisfied respondents are nonpopulist. All associations between life dissatisfaction and attitudes are statistically significant (Populism: X 2 = 77.48, p < 0.001; Nativism: X 2 = 42.82, p < 0.001).

Structural equation models

Figure 1 displays the paths linking life dissatisfaction to populist and nativist attitudes in the most restrictive main model 4 (see stepwise-estimated models in Appendix A6). The highest power (CD) can be found in the most developed model (4), yet the best model fit is attained when controlling for sociodemographics and economic attitudes, but not the full span of political attitudes. Notably, the CFI, TLI, and RMSEA slightly worsen with the inclusion of political attitudes, while the SRMR stays unchanged (see A6 3&4). While CFI and TLI in model 4 are slightly below the conventional cutoff point (<0.90), the residuals are low (RMSEA < 0.06, SRMR = 0.05). We thus conclude that the overall fit of models 3 and 4 is adequate for further analyses.

Globally, we observe that life dissatisfaction significantly relates to higher scores on populism. Life dissatisfaction is associated with an average absolute increase of 0.18 in populist attitudes, net of the effect of sociodemographics, economic concerns, and political attitudes (A6). The effect of low SWB is robust to the inclusion of different kinds of economic discontent or worries. We only find a weak association between self-centered economic concerns and populist and nativist attitudes, indicating that life dissatisfaction is not only a reflection of personal economic circumstances and expectations. By contrast, we find some correlation between society-centered economic concerns and populist and nativist attitudes, echoing earlier evidence (Elchardus and Spruyt, Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Capelos and Katsanidou, Reference Capelos and Katsanidou2018). In relative terms, the (standardized) relationship between life dissatisfaction and populist attitudes is stronger than the influence of societal economic discontent. While perceptions about the state of the economy surely matter for populist sentiment, the data suggests that life dissatisfaction is a stronger correlate of citizens’ adherence to populist ideas. It seems past research may have underestimated the influence of self-centered, non-pecuniary forms of discontent on populist and nativist attitude formation, beyond gloomy perceptions about the national economy and one’s personal finances.

While life dissatisfaction is related to an average absolute increase of 0.26 in nativist attitudes net of sociodemographic and economic controls (model 3), adding political attitudes in model 4 weakens the relationship below conventional statistical significance. We interpret this change as an indication that low SWB is more consistently associated with the ‘purely populist’ than the ‘ideological’ base of RWP support (Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2017). Since low SWB correlates more strongly with populist than nativist attitudes in the FNES data, the linkages between well-being and demand-side populism could plausibly be independent of the latter’s ideological anchoring. This paves the way for also considering low SWB as a possible predictor of left-wing populism in future studies.

Robustness checks

We tested whether the sociodemographic profile, economic or political attitudes moderate the relationship between low SWB and the attitudes (see Appendix A7a–7d). There was very little evidence of moderation in the models. Although the correlation between life dissatisfaction and populist attitudes strengthens with age, economic, or political attitudes do not emerge as significant moderators. We also estimated the main models using OLS regression (see Appendix A8a–8d) that allows us to fully consider the noncompensatory characteristic of populist attitudes. While SEM has the advantage of controlling for measurement error when examining the attitudes, the latent attitudes are composed of linear combinations of their underlying items. By contrast, the dependent variables in A8 are Goertz-corrected composite indices where a high score on one subdimension does not compensate for a low score on another dimension. The results in A8 also respond to criticism on how SEM relies heavily on a good theoretical model that a researcher makes by including variables and paths in the model (‘strong’ and ‘weak’ causal assumptions), while ordinary regression analysis includes predictors in a merely ‘informational’ way (that is, does a predictor explain variance in the dependent variable). Nativist attitudes appear more influential in the OLS models than in SEM (Figure 1), while the opposite holds for populist attitudes. The divergent results suggest that aggregation method matters for defining constructs such as populism and nativism. It may be that some items have disproportional influence on the nativism scores when simply aggregating across items (in OLS), instead of assigning unique weights to the items as SEM does.

In Appendix A9, we consider subjective state of health as a possible confounder, as it also reflects respondents’ mental health and has been linked to RWP support in Europe (Kavanagh et al., Reference Kavanagh, Menon and Heinze2021). The results for life dissatisfaction in relation to populism remain robust, while its net influence in relation to nativism is strengthened when self-rated health is considered, underlining the close relationship between SWB and health. Also, we check in Appendix A10 if life dissatisfaction captures the influence of an extended set of attitudes including political trust, political interest, political knowledge, or income dissatisfaction. The influence of SWB is dramatically reduced and falls under conventional statistical significance when controlling for these additional covariates. For populist attitudes, the change seems to primarily be driven by the combination of political distrust, external efficacy, and dissatisfaction with democracy, all three being closely related constructs and strongly predictive of populist attitudes (Geurkink et al., Reference Geurkink, Zaslove, Sluiter and Jacobs2020). The conventional interpretation is that in the less restrictive models, SWB captured the influence of omitted covariates, and political trust notably. Yet, it shall be kept in mind that the conceptual relationship between the abovementioned constructs is unclear. For instance, it remains debated whether political distrust strongly predicts, mediates, can result of, or is essentially the same as the anti-elitist component of populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Zaslove and Spruyt2017; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2018). The conceptual and empirical partial overlap of these concepts complicates the ability to disentangle the unique contributions of each variable in the model, which would advocate use of a simpler model (Figure 1).

In Appendix A11, we test how a reverse relationship from populist and nativist attitudes to life dissatisfaction would look like. The results suggest that life dissatisfaction performs better in predicting populist attitudes than the reverse, while for nativist attitudes, the relative magnitude of the effects are similar, possibly due to recursiveness (cf. Welsch et al., Reference Welsch, Bierman and Kühling2021). Albeit only a preliminary test of causality, our analyses support the theoretical standpoint that low SWB is first and foremost a source rather than an outcome of populist sentiment.

Exploratory analyses

Being populist and nativist does not necessary imply being supportive of an RWP party. For instance, persons may be dissatisfied with established politics but also demand expert decision-making in politics (Esteban and Stiers, Reference Esteban and Stiers2021). Therefore, we also preliminarily explored if life dissatisfaction could indirectly relate to sympathy for the Finns party through our dependent variables, i.e., populist and nativist attitudes (the mediators) (see Appendices A12&A13). We found no indication of a direct relationship between low SWB and Finns party support, but the indirect relationship stemming through populist and nativist attitudes is statistically significant. The results illustrate how the influence of voter low SWB can spill over to RWP party preferences when populist and nativist attitudes are activated. Consequently, future studies are encouraged to explore the underlying psychological mechanisms that explain RWP success through crucial mediating variables such as populist and nativist sentiment.

Discussion

We have argued that life dissatisfaction is an overlooked correlate shedding new light on the psychological underpinnings of populist and nativist attitudes. The FNES data partially backs this claim. Hypothesis 1 (populist attitudes) stands the test of inclusion of many political attitudes, but hypothesis 2 (nativist attitudes) is only supported when economic discontent (but not political efficacy, satisfaction with democracy, social trust and left-right orientation) are considered. Furthermore, jointly considering many additional covariates that are intimately linked with populist attitudes (notably political distrust, external political efficacy and democratic dissatisfaction) weakens life dissatisfaction as a robust predictor of populist sentiment. While life dissatisfaction clearly relates to populist sentiment, its influence is not unique of attitudes that strongly link with the anti-elitist and anti-pluralist nature of populist attitudes.

What do these nuanced results tell us about the interconnections between SWB and populist and nativist attitudes? Firstly, life dissatisfaction is distinct from current economic discontent or worries about the (future) economy, whether self- or society-centered. We therefore call for more focus on the psychological explanations to populism and nativism that reflect people’s state of mind and the evaluations people make of their own existence, instead of how they perceive the economic conditions they are immerged in. SWB provides a relevant framework for investigating the deeper psychological foundations from which populist and nativist sentiment feeds. We encourage more focus on citizen SWB in future populism research. While the unspecific nature of SWB, and life satisfaction in particular, allows persons to make a fully personal and unconstrained evaluation of their life quality, this is also the main drawback of the construct as it cannot reveal which domains persons draw from in expressing their well-being. To develop scholarship on the psychology of demand-side populism and nativism, we call for political surveys to collect more multidimensional data on SWB, including measures on affective and eudemonic well-being.

Our contribution complements past research on the linkages between SWB on RWP support (Herrin et al., Reference Herrin, Witters, Roy, Riley, Liu and Krumholz2018; Nowakowski, Reference Nowakowski2021; Ward et al., Reference Ward, De Neve, Ungar and Eichstaedt2021) by focusing on attitudes, instead of party preference or vote choice. Hence, our results describe the whole population, including non-voters who might score higher on populist and nativist attitudes. Moreover, the stronger relationship between life dissatisfaction and populist, rather than nativist, sentiment underlines the relevance of SWB for future populism research across its ideological attachments.

Could the contemporary surge of populist and nativist attitudes be traced back to widespread ill-being among a part of the electorate? Possibly, despite the observational nature of our study. If we acknowledge that populist and nativist sentiment are rising, these attitudes could feed from a deep, generalized life dissatisfaction, which has likely been building up among some citizens in the context of deep-rooted societal changes in afterwar Europe. The dissatisfaction is mirrored in citizen’s perceptions and attitudes about politics, political actors and institutions, and societal out-groups (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020). We call for future research to revisit the dominant conceptualizations of voter discontent and systematically consider alternative sources, such as SWB, when exploring the psychological foundations of populism and nativism in contemporary liberal democracies. We also speculate that low SWB could be the key psychological link that connects the structural (economic and cultural) framework to the proliferation of populist and nativist attitudes. While remaining outside our empirical reach, theory tells us that economic insecurity and alienation from dominant societal values and culture erode individual life satisfaction (De Cuyper and De Witte, Reference De Cuyper and De Witte2007; Grün et al., Reference Grün, Hauser and Rhein2010; Oesch and Lipps, Reference Oesch and Lipps2013) and predict RWP support (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Oesch, Reference Oesch2008). Structural change and low SWB could possibly emerge as a joint framework (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020) for explaining populist success in today’s democracies.

The cross-sectional data limits us to study associations, but not causation. We have discussed and empirically explored the possibility that populist and nativist attitudes provide a breeding ground for life dissatisfaction, however, research designs that allow a more rigorous causal disentangling between SWB and populist and nativist attitudes could significantly advance research. Moreover, although the supply-side RWP is similar in Finland to other Western European democracies, we cannot guarantee the generalizability of voters’ attitudes outside of the Finnish context. Since we found life dissatisfaction to correlate with populist (and under certain conditions, nativist) sentiment even in the proclaimed ‘happiest country in the world’, an association is also likely to exist in other countries with comparatively high well-being. Still, examining the linkages between SWB and populist attitudes cross-nationally would be useful. Thirdly, the lack of appropriate measures in the data to test for the uniqueness of SWB compared to some related constructs, notably relative deprivation, is a drawback. We have argued that relative deprivation is conceptually distinct from life dissatisfaction and draws from different primary sources (environmental factors versus self-image and mental health), likely making their expected contributions to populist and nativist sentiment distinguishable. Yet we cannot know in certain terms if life dissatisfaction is empirically distinguishable from relative deprivation, or which emotions and perceptions drives it. Therefore, future research should examine both overarching SWB indicators and measures of more specific psychological experiences in relation to populism, in order to disentangle which mechanisms most forcefully drive it. Relatedly, while the single-item life satisfaction scale has been widely used and validated as a satisfactory umbrella measure of SWB (Diener, Reference Diener2000), we cannot empirically distinguish whether the evaluative, affective or eudemonic components of SWB mainly drive its relationship with populist sentiment. Despite the individual variation in prioritizing life domains for SWB evaluations (Pavot and Diener, Reference Pavot and Diener2008), we cannot ascertain whether some life domains emerge as particularly influential for most voters’ life satisfaction and, by extension, their populist and nativist attitudes. Keeping this in mind, life dissatisfaction certainly provides valuable cues on how people’s experiences of their own existence, and populist and nativist sentiment interrelate. We believe that our study is a useful first step for investigating the linkages between the (un)happiness of the electorate and the rise of populist and nativist sentiment among the public.

Conclusion

The proposed well-being–perspective to explain the surge of populist and nativist attitudes offers an overarching psychological framework for understanding what makes the populist and nativist discourse so appealing in contemporary democracies. We show that life dissatisfaction relates notably to populist sentiment among the Finnish electorate, irrespective of various economic worries. In the absence of more fine-grained data on SWB, the results highlight the need to dig deeper into the individual evaluations about their existence to understand the resonance of populism in political and societal discourse. Even if the results suggest that life dissatisfaction has policy relevance, we need to know more about the underlying subjective experiences that drive these overarching measures of SWB, in order to evaluate policy responses. In the meantime, we can conclude that people’s negative psychological experiences about their own existence are strong barometers of populist sentiment. By extension, these experiences potentially threaten the foundations of liberal democracy by spreading mistrust and cynicism towards representative democracy and institutions, disregarding deliberation and the respect for pluralism of opinions, and increasing out-group hostility. Considering these implications, SWB and its underpinnings have likely entered to stay on the political research agenda.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000583.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their colleagues at the Social Science Research Institute of Åbo Akademi for their valuable comments on an early version of this paper, and the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that helped us to improve our research.

Financial support

No specific funding to report.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.