Introduction

In October 2020, the issue of nature restoration, as part of the European Green Deal (EGD), formally attained agenda status in the European Union (EU) when the European Commission (EC) decided to take it up in its 2021 Annual Work Programme. In announcing its policy agenda for the upcoming year, the EC committed itself to changing the issue’s extant status quo (SQ) by proposing nature restoration targets. However, various farm and forestry associations expressed their concerns about the political prioritization of the issue. In the preceding months, these groups pointed toward the economic strain legislative action would pose on their member companies. By contrast, a coalition of environmental organizations warmly welcomed the issue’s inclusion on the EC’s agenda. In their attempts to push for policy action, these advocates repeatedly emphasized the widespread support they enjoyed for their demands. This example illustrates the political battle over agenda-setting: whereas some interest groups seek to push their ‘dream’ issue onto the policy agenda, others attempt to prevent their ‘nightmare’ issue from attaining agenda status (McKay et al., Reference McKay2018).

With these crucial political struggles in mind, this paper aspires to shed light on interest groups’ agenda-setting efforts and influence in the EU. Specifically, we analyze the role of different types of information provision in gaining influence over the EC’s policy agenda. To do so, we combine insights from informational lobbying approaches with bureaucratic reputation theory. In this regard, the EC is traditionally characterized as an institution primarily driven by technical, economic, and legal information to design efficient policies, reflecting its aim to maintain its longstanding reputation as a responsible institution (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013; Majone, Reference Majone2002; Rauh, Reference Rauh2016). Accordingly, a stream of research on interest representation and stakeholder consultations finds advocates providing such expert information more likely to shape EU policy outcomes (e.g., Dür et al., Reference Dür2019; Klüver, Reference Klüver2013). However, these studies have mainly focused on later policy stages, neglecting the unique dynamics at play during agenda-setting. In contrast to previous work, we posit that when the EC acts as an agenda-setter it primarily seeks to identify and prioritize issues with broad audience support, thereby aiming to cultivate a newer reputation as a responsive actor (Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018; Koop et al., Reference Koop2022; Reh et al., Reference Reh2020). Consequently, we argue that groups focusing on information on audience supportFootnote 1 in their interactions with the EC to be more likely to wield agenda-setting influence than those emphasizing expert information.

Additionally, several studies emphasize the contingency of the influence enterprise on issue-specific characteristics (Klüver et al., Reference Klüver2015). Therefore, we explore to what extent our main expectation holds across varying levels of issue politicization. Despite the ECs’ overall tendency to be responsive to diverse societal perspectives during agenda-setting, considerable issue variation remains. Indeed, many issues escape the public spotlight and do not become the subject of fierce polarization and interest mobilization (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2020). Under these circumstances, the agenda-setting process could be primarily guided by evidence-based decision-making, favoring groups that emphasize expert information.

Addressing this matter has clear normative implications. The prevalence of information on the scope of audience support resonates well with the image of a pluralist and democratic political system, wherein institutional agenda-setters are open to societal pressures and demands (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). In this view, interest groups act as central intermediary organizations that aggregate societal interests and channel them into the policy process (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2020). Conversely, an excessive emphasis on expert information might introduce biases into the agenda-setting process by privileging a specific set of organizations with the financial means to acquire and present this costly policy good, possibly excluding other groups incapable of providing such information (Stevens and De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020).

Drawing on 37 expert interviews with EC officials and a content analysis of 818 media articles, we constructed a novel dataset that allows us to gain insight into the agenda-setting influence of 158 key ‘insider’ groups that directly accessed the agenda formation process of 65 specific policy issues. These issues are connected to the EGD, which provides a fruitful testing ground for interest groups’ agenda-setting influence. The EGD encompasses highly politicized cases (e.g., reducing pesticide usage) as well as issues that attract low salience, little polarization, and limited interest mobilization (e.g., promotion of inland waterway transport). Moreover, our focus on the impact of ‘insider’ groups is important as these organizations are often anticipated to advocate for their own interests, potentially at the expense of representing EU constituencies (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016).

Our results highlight that groups focusing on information linked to the scope of audience support are more effective in their agenda-setting efforts than those emphasizing expert information. However, the beneficial effect of stressing audience support is contingent on the degree of issue salience and the level of interest mobilization. When EU politics is ‘noisy’, information on audience support carries the day. However, under ‘quiet’ politics, patterns of agenda-setting influence do not systematically vary across advocates opting for different modes of informational lobbying. Overall, our results thus indicate that the EC is largely driven by concerns about its reputation for responsiveness when making decisions about its policy priorities, particularly in circumstances of noisy politics. Consequently, our study challenges the oft-repeated characterization of EC decision-making as solely technocratic, albeit highlighting the pivotal role of issue salience and interest mobilization in inducing a responsive mode of agenda-setting.

Conceptualizing agenda-setting influence

Although the question of interest group influence has provoked significant controversy in the political science discipline, studies analyzing agenda-setting influence are scarce. Most empirical work focuses on how groups react to policy agendas by assessing policy influence, referring to an actor’s ability to bring policy outcomes closer to an ideal point and attain its position during the policy formulation and decision-making stages (Dür et al., Reference Dür2019; Klüver, Reference Klüver2013; Stevens and De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020). Nevertheless, as Lowery critically remarks, looking at legislative lobbying is ‘simply beside the point if the agenda itself is shaped via an even deeper level of influence, largely rigging the game before it has even begun’ (2013, p. 8). Influencing the policy agenda holds significant importance for interest groups as it delineates the scope of their advocacy efforts in subsequent stages. The policy formulation process, involving the discussion of various policy alternatives, only commences when an issue reaches the formal agenda (Stevens, Reference Stevens2023). In contrast, when an issue is kept off the agenda, different policy options remain unexplored and no decision-making is possible (Bachrach and Baratz, Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962). In essence, without an issue gaining agenda status, the existing SQ – either the absence of policy or the maintenance of the extant policy framework – persists.

In this study, we refer to interest groups’ agenda-setting influence as control over the formal agenda status of specific issues. This conceptualization centers on the extent to which groups’ agenda goals correspond with the formal status of an issue at a given point in time to be either on or off the agenda as a result of their visible issue engagement (Lowery, Reference Lowery2013). As such, we consider interest groups to be influential agenda-setters when they successfully push their ‘dream’ issues onto the formal agenda while effectively keeping their ‘nightmare’ issues off the formal agenda (Bachrach and Baratz, Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962; McKay et al., Reference McKay2018). Notably, interest groups’ preferences are issue-specific: a single lobby actor may conceive one issue as a ‘dream’ to be realized while considering another a ‘nightmare’. To be precise, when policymakers introduce any alternative to the existing SQ, the issue is ‘on the agenda’ (Kreppel and Oztas, Reference Kreppel and Oztas2017). Conversely, an issue is ‘off the agenda’ when policymakers choose to discard policy change. Within the EU, an issue formally achieves agenda status when the EC incorporates it into a first draft proposal, which may manifest in diverse formats (e.g., a Green or White Paper, a Communication, a Working Paper, or an Annual Work Program). After this formal issue prioritization, further policy formulation kicks off to reach an official legislative proposal that can be sent to the co-legislators.

Our notion of agenda-setting influence has two important implications. First, an ‘issue’ is not conceived as a broad policy area such as ‘Environment’ or ‘Energy’ but is defined as a specific policy topic on which actors may have differential views regarding its agenda status. Hence, we squarely focus on what most interest groups direct their lobbying efforts at to defend the interest of their delineated sub-constituencies (Burstein, Reference Burstein2014). Focusing on broad policy areas would inevitably lead to a mismatch between what groups seek to influence and what is being analyzed. Second, our notion of agenda-setting entails actively constructing a formal agenda, including the decision to (or not to) introduce changes to the extant SQ (Kreppel and Oztas, Reference Kreppel and Oztas2017). This institutionalist conception of the agenda status of policy issues differs from a significant body of agenda-setting research defining agenda items as those that receive (at least some degree of) political attention but are not necessarily up for active policy formulation (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005). However, as Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960) eloquently put it: ‘the definition of the alternatives is the supreme instrument of power’ because if an interest group can shape the list of active agenda items, then this group is already shaping – to its benefit – the future policies that may come about.

Information, reputation, and agenda-setting influence

Following informational lobbying approaches (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2019; Schnakenberg, Reference Schnakenberg2017), we argue that interest groups can gain agenda-setting influence by strategically highlighting different types of information in their interactions with policymakers. To that end, we first elaborate on the types of information interest groups can emphasize in their interactions with public officials. However, given that interest groups’ influence depends on policymakers’ perceived value of their informational assets (Hanegraaff and De Bruycker, Reference Hanegraaff and De Bruycker2020), we subsequently discuss the ECs’ reputational-building efforts and accompanying informational requirements when acting as an agenda-setter. We thus draw on supply–demand dynamics to characterize the relationship between interest groups and EC policymakers (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002). Based on this interplay between information supply and demand – instructed by reputational concerns – we expect interest groups emphasizing audience support to be more influential agenda-setters than groups focusing on expert information.

Information supply – Information is a crucial resource for interest groups to realize their political objectives. This information is issue-specific, often aggregates various viewpoints into a common stance, and comes with ready-made policy priorities thanks to groups’ direct involvement with affected constituencies (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016; Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2019). Hence, interest groups hold specialized knowledge, granting them informational advantages over policymakers (Schnakenberg, Reference Schnakenberg2017). If policymakers depend on a group’s information and make decisions aligning with the organization’s requests, this signifies a level of influence since political decisions would have been different without this information provision (Tallberg et al., Reference Tallberg2018).

In this context, interest groups may emphasize different information types in their agenda-setting efforts. First, groups may focus on expert information by underlining the feasibility of legislative action, its economic costs or benefits, and compatibility with existing legislation or potential legal overlaps (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). Groups can obtain expert information for a specific issue by developing in-house research programs, hiring expert staff, or buying external expertise for specific policy issues (Stevens and De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020). They can subsequently emphasize this information in their interactions with policymakers to demonstrate a solid understanding of the issue at hand, which may help them make a stronger case for their demands. Conversely, advocates may emphasize information on the level of audience support by referring to public preferences or the demands of members and supporters (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2020). Through their interactions with members and supporters or by closely monitoring the public mood, interest groups can collect information on the scope of support they enjoy for their agenda views. This, in turn, may help them pursue agenda-setting influence as it highlights the representativeness of their objectives (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002). In sum, some advocates may consider providing expert information as more relevant, while others prefer to focus on information on audience support (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2019).

Reputation & Information demands – In this study, we focus on the agenda-setting decisions of the EC, the EU functional equivalent of a national government (Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018). Through its exclusive right of initiative, the EC determines which issues enter the formal policy agenda and which ones do not. In this role, the EC – like any other executive – demonstrates high selectivity in prioritizing policy issues. Individual EC policymakers persistently face multiple issues competing for their attention. However, limited attention spans constrain their capacity to tackle them all (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005). Although the EC’s functional differentiation into specialized Directorate Generals (DGs) assists in off-loading demands from the political leadership, each organizational unit is still faced with a wide range of issues within its specialization while being time- and resource-constrained (Princen, Reference Princen2013). Moreover, organizational specialization inherently steers DGs to focus on issues within their expertise, inadvertently leaving others unattended. And although the EC can simultaneously monitor multiple issues thanks to its functional specialization, any issue seriously considered for attaining agenda status is eventually deliberated by the political leadership, which is similarly constrained (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005). Consequently, there is a persistent mismatch between numerous issues calling for the EC’s attention and its finite capacity to address them all. This mismatch drives the agenda-setting process: some issues reach the formal agenda while others remain unattended (Green-Pedersen and Walgrave, Reference Green-Pedersen and Walgrave2014).

In contrast to national governments’ agenda decisions, however, the policy priorities of the EC are not driven by the pursuit of votes or fear of electoral consequences (Koop et al., Reference Koop2022; Reh et al., Reference Reh2020). Instead, the EC follows a reputational logic, establishing its legitimacy based on how its actions are perceived by various audiences in the environment in which it is embedded (Busuioc and Rimkutė, Reference Busuioc and Rimkutė2020). These audiences critically assess and judge the EC’s decisions, either upholding or undermining its legitimacy. In this context, reputation refers to ‘a set of symbolic beliefs about the unique or separable capacities, roles, and obligations of an organization’ (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2010, p. 45). Applied to the EC, scholars have pointed to its established reputation as a responsible actor known for efficiently generating policy output (Bunea and Nørbech, Reference Bunea and Nørbech2023; Rauh, Reference Rauh2016) as well as its newer reputational concerns to be a responsive institution attuned to the level of support for EU action among societal audiences (Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018; Reh et al., Reference Reh2020). Both types of reputation are constructed in the interplay between the EC’s performance and how multiple audiences perceive it. Audiences can cause reputational threats – and undermine legitimacy – if they perceive the EC to not deliver on its core tasks, while they are likely to uphold the EC’s good reputation when positively evaluating its task execution (Rimkutė, Reference Rimkutė2018).

While several studies have effectively employed the reputational lens to scrutinize the EC’s decision-making as a policy designer (Bunea, Reference Bunea2019) and a rule enforcer (Finke, Reference Finke2022), recent research has shed light on another crucial responsibility of the EC: its formal authority over agenda-setting (Koop et al., Reference Koop2022; Reh et al., Reference Reh2020). This latter stream of literature suggests that the EC’s agenda-setting decisions are similarly shaped by its quest for reputation. Indeed, the EC uses its policy priorities as a signaling device to bolster its reputation: by engaging with issues that foster good reputation while refraining from those that pose reputational risks, the EC can effectively build legitimacy in governance.

In this context, the EC can use its policy agenda to either reinforce its reputation as a responsible actor or cultivate an image as a more responsive institution. On the one hand, the responsible mode of reputation-building is consistent with evidence-based decision-making over policy priorities, underpinned by expert knowledge, and insulated from politicization and public scrutiny (Bunea and Nørbech, Reference Bunea and Nørbech2023). To foster a responsible reputation, the EC depends on information on the feasibility of legislative action, its economic costs or benefits, and its compatibility with existing legislation or potential legal overlaps (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). On the other hand, the responsive mode of governance is linked to being more receptive to inputs from citizens and interest groups, aligning with a more societally accountable and politicized agenda-setting process (Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018; Koop et al., Reference Koop2022; Reh et al., Reference Reh2020). To act responsively, the EC requires information regarding public preferences and demands input from different subgroups to evaluate the societal necessity for action. Building a reputation for responsiveness is vital to achieving input legitimacy, but cultivating a reputation for responsibility is essential to building output legitimacy (Bunea, Reference Bunea2019).

The supply-demand interplay – However, like other public organizations, the EC must balance its multifaceted reputation (Busuioc and Rimkutė, Reference Busuioc and Rimkutė2020). Achieving this balance can prove challenging and may lead to conflicts, given that decision-making based on expertise might not align with the necessity to consider diverse societal perspectives (Bunea and Nørbech, Reference Bunea and Nørbech2023). Existing research has extensively documented the EC’s concentration on establishing its reputation as a responsible institution (Majone, Reference Majone2002; Rauh, Reference Rauh2016). Likewise, studies on EU interest representation indicate that expert information takes precedence in engagements with the EC (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002; Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). However, this body of research has mainly focused on the EC’s reputational concerns and accompanying information requirements, either when deliberating complex policy options as a policy designer or implementing specific measures as a rule enforcer. These roles often exhibit a more technocratic nature and tend to be depoliticized, fostering the EC’s inclination toward adopting a responsible approach to decision-making (Truijens and Hanegraaff, 2023).

In contrast, we posit that when the EC acts as an agenda-setter, its primary focus lies in fostering a responsive reputation (Bunea and Nørbech, Reference Bunea and Nørbech2023; Koop et al., Reference Koop2022). While scholars have acknowledged different informational needs across institutional settings, reputation theory stresses the distinct, sometimes conflicting, needs within a single institution (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz2023; Busuioc and Rimkutė, Reference Busuioc and Rimkutė2020). In this vein, we argue that the EC’s approach to reputation-building and its associated informational needs vary depending on its legislative tasks. As an agenda-setter amidst a contentious environment, the EC seeks to actively ‘listen’ to a broad range of audiences (Giurcanu and Kostadinova, Reference Giurcanu and Kostadinova2022; Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018; Reh et al., Reference Reh2020) and use its agenda-setting authority as a strategic tool to ‘respond’ to societal demands (Koop et al., Reference Koop2022). By carefully prioritizing broadly supported issues while avoiding heavily opposed ones, the EC can establish and maintain its reputation as a responsive institution. Consequently, the EC demonstrates a keen interest in accurately gauging the extent of audience support for the multitude of issues demanding attention (Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018). However, achieving this objective necessitates understanding the varied composition of its societal audiences, each distinguished by unique interests and viewpoints (Meijers et al., Reference Meijers2019). Through dialog with interest groups articulating signals of support, the EC can gain such understanding, enabling a better evaluation of the level of audience support.

Considering the EC’s informational needs during the agenda-setting stage, we expect that interest groups emphasizing audience support information are more successful in influencing the agenda status of policy issues than those focusing on supplying expert information. These organizations aid the EC in mitigating uncertainty regarding the political urgency of and support for issues (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2020; Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018). In turn, the EC is incentivized to listen and respond to advocates signaling the scope of audience support to boost its reputation as a responsive agenda-setter. Disregarding these signals might pose reputational risks and raise concerns about a lack of input legitimacy (Bunea, Reference Bunea2019; Reh et al., Reference Reh2020). Conversely, while expert information remains relevant, its impact on agenda-setting influence is relatively lower due to the EC’s emphasis on responsiveness.

Hypothesis 1: Groups primarily providing information on audience support instead of expert information are more likely to attain agenda-setting influence.

The role of issue politicization

In the preceding section, our argument highlighted the EC’s inclination toward information on audience support during the agenda-setting stage. Nevertheless, significant variation persists across issues (Klüver et al., Reference Klüver2015). We therefore anticipate that the EC’s concerns regarding reputation and its corresponding informational needs vary not only due to its legislative role but also across issues during the agenda-setting process.Footnote 2 This, in turn, impacts the potential agenda-setting influence groups can achieve. Specifically, we explore the extent to which our main argument holds across levels of issue politicization. Politicization is commonly conceptualized along three dimensions: salience, polarization, and actor expansion (see Hutter and Grande, Reference Hutter and Grande2014). While these three components appear in many studies of politicization, how they are labeled, conceptualized, and operationalized varies depending on whether studies focus on party politics, public opinion, or the mass media (de Wilde et al., Reference de Wilde2016). In this vein, our attention is directed toward three pertinent aspects of politicization for a study centered on interest groups (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2020; Willems, Reference Willems2020): the importance of the issue (salience), the degree of interest mobilization (actor expansion), and the intensity of disagreement among mobilized groups (polarization).

Following this, the ECs quest for a responsive reputation can be expected to become a focal point of concern on intensely politicized issues or circumstances of ‘noisy’ politics. When politics is ‘noisy’, the EC is incentivized to listen primarily to arguments about support for or opposition to policy action among relevant audiences (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2020). Despite the potentially overwhelming influx of audience-related information in times of ‘noisy’ politics, interest groups continue to serve as pivotal intermediaries between society and policymakers (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2020). Politicization implies that signals of audience support and opposition may collide. Here, groups provide a succinct, focused, and collective information signal that can pierce through a crowded and complex information environment, allowing the EC to effectively use it to support their agenda decisions. Simultaneously, we examine whether responsible decision-making over policy priorities, guided by expert information, becomes relatively more important once issues are deliberated under circumstances of ‘quiet’ politics (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2011). Without politicization, the EC’s inclination toward evidence-based agenda-setting is arguably more profound. With less societal pressure being present, the EC has the leeway to rely more heavily on expert information to ensure the effective implementation of its policy priorities (Stevens and De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020). In what follows, we discuss how the three dimensions of politicization affect the relative importance the EC attaches to information types and, consequently, how interest groups can use their privately held information as a resource to gain agenda-setting influence.

Salience – Salience refers to the relative importance actors attribute to a specific policy issue (Beyers et al., Reference Beyers2018). When an issue draws the attention of key audiences, it influences their grasp of its implications. Heightened salience then prompts a more responsive decision-making approach within the EC, compelling it to be attentive and receptive to audience pressures (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2020; Stevens and De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020). Faced with an attentive audience, the EC encounters challenges in diverging from or dismissing appeals from constituencies for action or restraint (Reh et al., Reference Reh2020). Failing to respond under such circumstances poses a risk to its reputation. Therefore, when a group highlights audience information, it can help the EC assess the audience support level for addressing an issue. In turn, the organization increases the likelihood of advancing its political goals – specifically, influencing the inclusion or exclusion of an issue from the policy agenda. Conversely, the EC is less vulnerable to pressure tactics when relevant audiences assign little importance to an issue (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2011). In such situations, it faces little pressure and relies less on the backing of societal audiences. As scrutiny of its actions diminishes, the threat to the EC’s reputation as a responsive actor also diminishes.

Hypothesis 2: The more salient a policy issue, the more likely groups primarily supplying information on audience support instead of expert information attain agenda-setting influence.

Polari z ation – Polarization is determined by the degree to which interest groups hold diverging views about the agenda status of a policy issue (Dür et al., Reference Dür2019). When conflicts or disagreements arise, the EC faces an increased necessity to justify and legitimize its political decisions. This necessity occurs because audiences pay more attention to the differing sides of the debate, with conflict serving to solidify opinions (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2020). In such scenarios, the EC relies more on information regarding audience support to sway the agenda status toward a specific direction. By considering divergent societal views when making its agenda decisions, the EC bolsters its reputation by demonstrating a willingness to acknowledge conflicting perspectives. However, there are many instances where issues are advocated by a single interest group without opposition or mobilization from any other organization (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner2009). Under these circumstances, the EC relies less on audience support to tip the balance toward a political compromise. Little controversy among involved interest groups signals a (latent) consensus about the issue’s agenda status. Information on audience support then holds little leverage for shaping the policy agenda. In sum, we expect that a greater reliance on information on audience support is more likely to result in agenda-setting influence when a policy issue is highly conflictual:

Hypothesis 3: The more polarized a policy issue, the more likely groups primarily supplying information on audience support instead of expert information attain agenda-setting influence.

Interest mobili z ation – Third, the level of interest mobilization pertains to the number of mobilized groups on an issue seeking to shape its agenda status. While some issues are characterized by only a few mobilized organizations, others attract a more widespread and diverse set of organized interests (Willems, Reference Willems2020). This has profound consequences for the EC’s preference for distinct types of information. The more organizations mobilize, the higher the volume of voiced demands and the more intensified political debates. Such heightened mobilization puts pressure on the EC to listen and respond to the diversity of expressed demands, making them more sensitive to the level of support signaled. Conversely, if issues are debated among a small set of interest groups, when the volume of demands the EC faces is lower, it will experience less societal pressure to act responsively (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2020). Under these circumstances, the beneficial role of emphasizing information on audience support for gaining agenda-setting influence is expected to decrease.

Hypothesis 4: The more interest mobilization on a policy issue, the more likely groups primarily supplying information on audience support instead of expert information attain agenda-setting influence.

Methodology

Case selection and sampling

We assess our hypotheses on issues related to the EGD, which has several advantages. First, the EGD provides a fruitful testing ground because it encompasses a wide range of policy areas in which the EU has clear competencies. Second, issues debated under the EGD vary considerably in salience, polarization, and interest mobilization levels. Third, organizations mobilizing on these issues differ in policy views, interests represented, and lobby tactics. Our focus thus assures variation in the main explanatory variables.

The lack of a single sampling frame covering all possible issues presents a challenge when conducting interest group studies. In our case, policy issues come from 37 structured online interviews with EC officials conducted between February and June 2022. The setting of the EGD thus delivers practical advantages as it is a recent package of policy initiatives, ensuring good recall and accessible case memories among interviewees. Moreover, in contrast to observational data sources (e.g., legislative databases), expert interviews allow for identifying issues that did not make it onto the policy agenda. Finally, contrary to surveys, interviewing policy experts lets one firmly grasp each policy issue’s substance.

We approached 50 relevant EC units, selected based on prior contact with the EGD coordinating units and desk research. In total, we interviewed a respondent – either a (deputy) head of unit, team leader, or policy officerFootnote 3 – for 37 units (response rate of 74%). All respondents had well-circumscribed responsibilities to develop EGD initiatives in their respective policy areas and commanded detailed knowledge of the agenda negotiations. We conducted at least one interview for each of the following key elements of the EGD: climate action, clean energy, circular economy, buildings and renovations, sustainable mobility, eliminating pollution, farm-to-fork, preserving biodiversity, and green alliances. Appendix A1 provides an overview of the issue distribution across policy areas. In each interview, respondents were asked to identify two specific policy issues: one issue that attained agenda status and one discussed with stakeholders (including interest groups, other EC services, party groups, and the Member States) but eventually not prioritized. Our negative cases are thus chosen based on the ‘possibility principle’: in theory, the issue could have come onto the EC agenda as at least one actor was calling for political action, but in reality, it was not taken up (Mahoney and Goertz, Reference Mahoney and Goertz.2004). We deliberately guided respondents to specify one issue that reached the agenda and another that remained unattended to mitigate the likelihood that respondents would only recall active agenda items. This is key to ensure that our sample was not skewed toward instances of successful positive agenda-setting and failed negative agenda-setting. Moreover, respondents’ time limitationsFootnote 4 necessitated selecting only one issue from either side. Despite these constraints, Appendix A2 shows that our issue sample encompasses considerable variation in relevant issue characteristics.

In total, we have 65 unique issues, of which 33 attained agenda status and 32 did not.Footnote 5 An example of an active agenda item is a ban on bottom-trawling – a fishing method that involves dragging a large, weighted net along the seafloor to catch fish and other seafood that live near the bottom – in protected sea areas. An example of an issue that did not attain agenda status is the reduction of track access charges – i.e., the fees paid by railway companies to infrastructure managers for using railway tracks and related facilities. Once respondents identified an issue, they were guided through a closed-ended questionnaire on the issue’s characteristics, the preferences of various interest groups involved, and their interactions with these groups. Through the interviews, we identified 158 active interest groups. Our unit of analysis is thus one interest group active on one of the sampled issues. In the remainder, we denote these observations as group-issue dyads. We analyze 297 group-issue dyads since several groups, but not all, appear more than once. On average, groups appear two times in the dataset, with one organization appearing sixteen times.

Operationalization of variables

Dependent variable – Although operationalizing agenda-setting influence is challenging, significant consensus exists around triangulating different measures to achieve a more exhaustive understanding and reliable results (Dür, Reference Dür2008). In this study, we rely on two measures of agenda-setting influence: a preference attainment measure (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner2009) and an attributed influence score by public officials (Albareda et al., Reference Albareda2023). For the preference attainment measure, we rely on data from the interviews with EC officials (Dür et al., Reference Dür2019). Specifically, we rely on their responses about organizational preferences (supporter or opponent of policy change) and the agenda status of the issues (either on or off the formal agenda). Relying on EC responses is a suitable way to construct an agenda preference attainment measure considering EC officials are, compared to interest groups, better informed about the actual agenda status of issues. Moreover, they provide a more reliable picture of what groups want to achieve in agenda negotiations, while interest groups are arguably more inclined to proclaim support for action for reasons of social desirability. We classified groups as ‘Influential’ if their preference and the agenda status match (=1) while categorizing them as ‘Not influential’ (=0) if they did not secure a match. We thus assess whether the organization got what it wanted in terms of issue prioritization (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner2009; Klüver, Reference Klüver2013). The main advantage of this measure is that it does not rely on potentially biased influence perceptions of respondents. Still, an agenda preference attainment score comes with methodological challenges. Most notably, the convergence of actors’ stances regarding the prioritization of an issue and its agenda status is not necessarily the result of direct group influence but might be ‘luck’; scholars therefore often speak of ‘success’ instead of influence (Lowery, Reference Lowery2013).

Therefore, we combine this measure with an attributed agenda-setting influence score (Albareda et al., Reference Albareda2023). After identifying active organizations on a policy issue, EC officials were asked to identify influential groups; those able to significantly impact the issue’s agenda status. If a group was mentioned, they were coded as ‘Influential’ (=1), while groups not listed were coded as ‘Not influential’ (=0). The main advantage of this measure is its likely ability to detect causality since asking EC officials to gauge the organizational impact on the agenda-setting process implies they understand the relationship between cause (the groups’ actions) and effect (their decision (not) to address an issue). Measuring attributed influence thus allows moving beyond the frequently used concept of agenda-setting ‘success’ associated with preference attainment measures. Nevertheless, attributed influence scores inherently capture subjective influence perceptions held by some but not necessarily shared by others. Furthermore, respondents may strategically exaggerate influence or report modestly about agenda-setting influence to avoid public disapproval.

Explanatory variables – To evaluate the specific type of information provided, we posed the following question to our respondents: ‘In your discussions on this policy issue during the agenda-setting stage, could you indicate what type of information each organisation primarily provided to you?’. Respondents could indicate whether a group primarily offered information related to technical, legal, or economic aspects of policy action, or if their emphasis was predominantly on public preferences or constituency support. This process resulted in a binary variable, wherein an organization was categorized either as prioritizing expert information (=0), or information related to audience support (=1). A chi-square test of independence was performed to test whether information provision drives the results and not group type. While the relationship between these variables was significant, X 2 (2, N = 332) = 50,66, p < 0.01, the link is relatively weak (Φ = 0.39).

The three dimensions of politicization were operationalized as follows. First, to capture issue salience, we manually collected relevant media coverage between January 2019 and June 2022 from three news outlets (Politico, EUObserver, and Euractiv) for all issues.Footnote 6 With this operationalization, we assess salience beyond the assessment of one particular type of actor. Media content incorporates the actions and statements of various EU policy participants, such as policymakers, journalists, interest groups, and citizens (Beyers et al., Reference Beyers2018). Appendix A4 outlines the selection of relevant news articles and their distribution across the three outlets. In total, 818 articles were identified. In the analyses, we use the mean number of articles per issue across the three selected outlets. The Cronbach’s alpha for the three salience items was 0.70, which is sufficiently satisfactory. Next, the level of polarization was measured by taking the ratio of the number of interest groups mentioned in the interviews that supported policy action over the number of organizations that opposed it. So, each issue received a score ranging from 0 (unified) to 1 (completely polarized). Finally, to determine the degree of interest mobilization, we counted the number of groups respondents listed as active on the issue. Online Appendix A5 displays the correlations between the three variables.

Controls – We included various control variables in our models. First, business groups are often expected to be more influential in shaping the policy agenda due to their structurally privileged position in the political process (Dür et al., Reference Dür2019). We therefore control for group type, differentiating between ‘Business’ and ‘Citizen’ interests. Business groups are (umbrella) associations with firms or professionals as members, while citizen groups are (umbrella) associations with individuals as constituents. Second, the more financial means a group has at its disposal, the more lobbying capacities (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner2009). Drawing on the Transparency Register (TR), we include staff size as the number of full-time equivalents employed at the Brussels office. Prior research has shown this to effectively indicate groups’ financial resources spent on lobbying efforts (Stevens and De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020). Thirdly, the agenda-setting influence of interest groups could be affected by the organizational structure of the EC. Previous studies have highlighted significant variations in reputational concerns among DGs, particularly between those focused on business and those oriented toward NGOs (Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018). Hence, we differentiate between DGs with an NGO-oriented focus and those with a business-oriented focus to account for potential organizational disparities. Lastly, we control for the support/opposition from other relevant political actors: the general public, Member States, and the European Parliament (EP). These three variables were measured using 148 interviews with interest group representatives (see online Appendix A6). Specifically, we therefore rely on interest groups’ responses to the following question: ‘Could you indicate how this issue relates to other issues you are familiar with regarding the share of actors supporting the inclusion of this issue on the EC’s agenda?’. Respondents were presented with a five-point scale ranging from ‘Much less support (=1)’ to ‘Much more support (=5)’ among the Member States, the Political Groups in the EP, and the general public. We rely on a relative assessment to create an ‘internal benchmark’ for evaluation among interviewees. We took the mean of all the responses for each issue to arrive at an intersubjective assessment of the scope of support.Footnote 7

Analyses

Before examining our hypotheses, we explore the distribution of the dependent variables. First, 178 (53.6%) organizations secured a match between their preferences and the issue’s agenda status. Second, public officials attributed agenda-setting influence to 139 interest groups (41.9%). Notwithstanding the limitations of each approach, our two measures gauging agenda-setting influence are significantly related (r=0.47, p<0.01), pointing at a similar underlying construct. Still, they capture distinct aspects of influence. Measures of attributed influence inherently capture perceived impact, while a preference attainment measure assesses the correspondence between agenda demands and the actual formal agenda status of issues. Therefore, we analyzed the impact of informational lobbying and issue politicization on agenda-setting influence in separate models.

Concerning our modeling strategy, the hierarchical structure of the data must be considered as interest groups are clustered into issues. Therefore, all models are run with random intercepts to account for the heterogeneity of different policy issues. Since our measures of agenda-setting influence were measured dichotomously, we estimate multilevel logistic regression models. Appendix A7 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables included in our models.

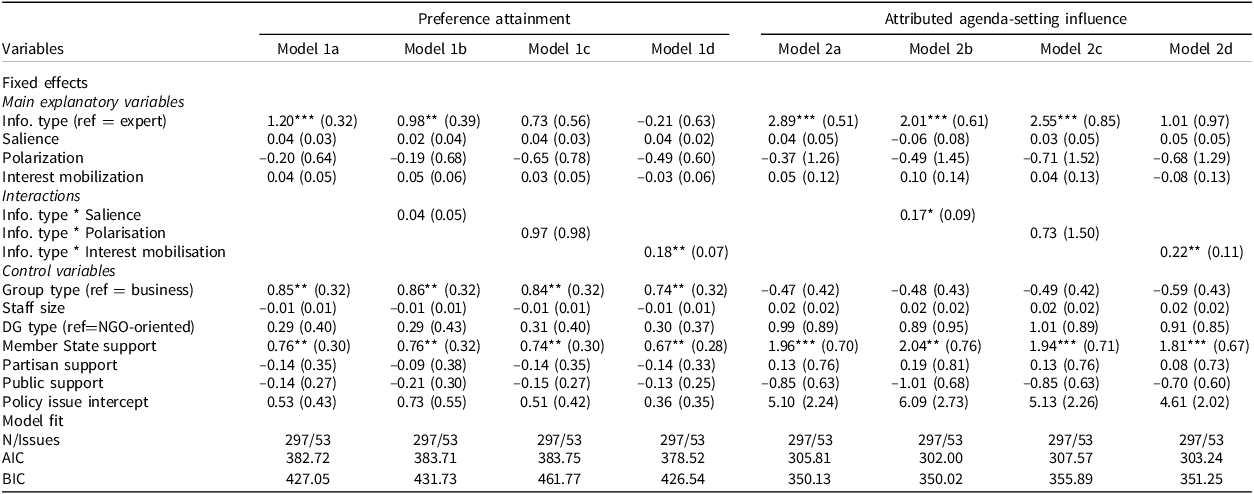

We evaluated the effect of our primary independent variable, the type of information supply (Hypothesis 1), in Models 1a and 2a in Table 1. The significant positive coefficients show that prioritizing information on audience support over expert information significantly increases the probability an interest group influences the agenda status of a policy issue. This finding supports Hypothesis 1, stating groups providing information on audience support instead of expert information are more likely to attain agenda-setting influence. The results align with recent studies suggesting that when deciding over policy priorities, the EC is primarily concerned with its reputation as a responsive actor (Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018). This contrasts with later decision-making stages, where research has indicated that the EC is more open to expert information provision, aligning with its aspiration to establish a reputation as a responsible institution (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013).

Table 1. Multilevel logistic regressions modeling agenda-setting influence

Note: Cell entries are estimated coefficients (with two-sided P values referring to H0 that β = 0 indicated for different significant levels: *if significant at the 0.10 level, **if significant at the 0.05 level and ***if significant at the 0.01 level) and standard errors are in parentheses. AIC: Akaike’s Information Criterion; BIC: Bayesian information criterion.

To assess Hypotheses 2-4, we interacted the type of information supply with the three politicization items and included them in Models 1b and 2b (Info*Salience); 1c and 2c (Info*Polarisation); and 1d and 2d (Info*Mobilisation). Overall, the positive interaction coefficients suggest that the beneficial effect of stressing information on audience support plays out in a nuanced manner. To further assess these interaction terms, we present predictive probabilities in Fig. 1. The middle panels illustrate that contrary to Hypothesis 3, stressing information about audience support is more effective than emphasizing expert information, irrespective of the intensity of polarization. Meanwhile, the upper and lower panels in Fig. 1 support Hypotheses 2 and 4, respectively, demonstrating substantial variations in the impact of information types across levels of issue salience and interest mobilization.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities (confidence interval = 90%) for distinct types of information provision across different levels of salience, polarization, and interest mobilization.

First, for issues characterized by low salience (average of one media article), interest groups emphasizing information about audience support do not experience a significantly lower likelihood of achieving their preferences (60.47%, SE=0.06) or gaining attributed agenda-setting influence (55.79%, SE=0.08) compared to organizations prioritizing expert information (respectively, 40.13%, SE=0.06 and 31.18%, SE=0.07. This finding demonstrates that when issues are debated outside the public spotlight, providing expert information can still be advantageous in gaining agenda-setting influence. Consider, for example, the association representing the inland port industry that effectively lobbied to improve transportation capacity for inland waterways, an issue receiving minimal media coverage, by prioritizing expert information. This organization was also recognized as influential in steering the agenda-setting process regarding their ‘dream’ issue. Conversely, in cases of high salience (averaging fifteen articles), interest groups providing audience support information exhibit a significantly higher probability of realizing their preferences (75.08%, SE=0.07) and being perceived as influential agenda-setters (70.28, SE=0.08) compared to groups relying on expert information (respectively, 43.86%, SE=0.08 and 20.45%, SE=0.08). This trend is, for instance, evident in the context of the highly salient issue of deforestation, where all five organizations identified as influential in both measures prioritized information on the level of audience support.

Second, for groups involved in issues marked by limited interest mobilization (involving three active organizations), prioritizing information about audience support does not result in a significantly lower likelihood of achieving their preferred outcomes (51.08%, SE=0.08), nor does it lead to a lower probability of attaining attributed agenda-setting influence (48.90%, SE=09), when compared to organizations primarily stressing expert information (respectively, 43.80%, SE=0.07 and 27.99%, SE=0.08). This finding is well exemplified by the association representing shipowners’ interests, which successfully prevented the inclusion of their ‘nightmare’ issue – stricter regulations on the carbon intensity of energy used by vessels – by emphasizing expert information. This organization was also perceived as an important driver of the agenda-setting process. In contrast, when dealing with issues attracting numerous interest groups (involving ten advocates), organizations emphasizing information related to audience support exhibit a notably higher probability of achieving their agenda objectives (69.81%, SE=0.08) and being perceived as influential agenda-setters (62.32%, SE=0.06), as opposed to groups emphasizing expert information (respectively, 41.28%, SE=0.05 and 24.83%, SE=0.06). A clear illustration of this finding comes from introducing a nonessential uses concept for chemicals in consumer products. On this issue, which attracted the involvement of several interest groups, all four organizations recognized as influential in both measures offered information regarding the level of audience support.

To enhance the robustness of our analysis, Appendix A8 presents models where the original three politicization items are replaced with perceived politicization measures. Here, EC officials were asked to assess whether each policy issue, compared to other issues, was ‘Much less (=1)’ to ‘Much more (=5)’ important to the public, polarized, and subject to interest mobilization. By integrating these perceived measures alongside our more objective indicators, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of how public officials subjectively perceive issues and how their perceptions subsequently influence the relative value they attach to different informational resources. Overall, our findings remain consistent, underscoring the reliability of our conclusions.

Our control variables also yield interesting insights. To begin with, citizen groups exhibit a significantly higher likelihood of accomplishing their preferred outcomes during the agenda-setting stage when compared to business groups. Nevertheless, the probability of attaining attributed influence does not systematically vary across both group types. Moreover, the mere presence of a larger staff size does not directly translate into agenda-setting influence. This finding emphasizes the need for analyses beyond the sheer counting of financial and human resources and instead examine how groups convert their resources into valuable policy goods and actively deploy them in their interactions with policymakers (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2019). Furthermore, we observe no systematic differences in interest groups’ agenda-setting influence across different DGs. Lastly, public, and partisan support for EU action do not significantly sway the likelihood of achieving influence in the agenda-setting stage. However, if a substantial number of Member States pushes for policy change, interest groups are more likely to secure agenda-setting influence.

Conclusion

This study assessed the role of information provision for interest groups’ agenda-setting influence by analyzing 65 policy issues – varying in agenda status – addressed by 158 active interest groups. As such, the contribution of this study is twofold. First, the prevailing focus in prior studies has primarily centered on how interest advocates respond to policy agendas and strive to achieve their policy preferences during the legislative stages of the policy process (Dür et al., Reference Dür2019; Klüver, Reference Klüver2013; Stevens and De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020). In contrast, this study shed light on a less visible facet of interest group influence. Specifically, it delved into their effectiveness in placing their ‘dream’ issues on the agenda while also preventing ‘nightmare’ issues from attaining agenda status. Doing so, this study addressed the challenges associated with empirically studying non-decision-making (Bachrach and Baratz, Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962). Within the agenda-setting literature, relatively many studies have focused on the rise of new issues on the policy agenda. However, agenda-setting is not just about which issues attain agenda status but also about which ones do not. Through expert interviews, this study elucidated how certain issues are successfully suppressed.

Second, we developed an argument illustrating how a supranational bureaucracy’s receptivity to different interest group inputs is connected to its quest for reputation (Bunea, Reference Bunea2019; Bunea and Nørbech, Reference Bunea and Nørbech2023). In this regard, our results concur with research underscoring the importance of the value policymakers attach to different information types depending on the policy stage in which they find themselves (Stevens, Reference Stevens2023). Unlike the later stages of the legislative process, our analyses reveal that the EC is predominantly driven by concerns over its reputation as a responsive actor when deciding over its policy priorities (Haverland et al., Reference Haverland2018; Koop et al., Reference Koop2022). Consequently, it tends to be more open to interest groups emphasizing information about the level of audience support. Moreover, high salience and interest mobilization reinforce this beneficial impact of signaling audience support or opposition. As such, our findings align well with prior research, stressing the need to account for the contextual nature of interest group politics to understand varying influence patterns (Klüver et al., Reference Klüver2015).

Our results have clear normative implications. On the bright side, our findings suggest a representative agenda-setting process in which the concerns and preferences of relevant audiences are heard and translated into policy priorities (Bevan and Jennings, Reference Bevan and Jennings2014; Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2004). Moreover, the beneficial impact of issue salience and interest mobilization on gaining agenda-setting influence through stressing the scope of audience support further enhances the view of interest groups as crucial intermediaries that ensure that policymakers respond to pressing societal concerns while refraining from heavily opposed issues (Bevan and Rasmussen, Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2020; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2020). Nevertheless, taking a more cautious stance, in situations where issues lack public visibility and only a limited number of groups mobilize, the effectiveness of providing audience support diminishes. Such circumstances of ‘quiet’ politics tend to favor organizations capable of carrying the costs associated with expert information provision, potentially biasing policy priorities (Stevens and De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020).

However, the results presented should not be overstated as they are limited to issues discussed in relation to the EGD, which could be regarded as a ‘most likely’ setting for finding a positive effect of agenda-setting influence through informational lobbying based on signaling audience support. The EGD is the flagship of the Von der Leyen EC. It would thus be reasonable to assume that the EC is going to great lengths to secure ample support for its policy priorities covered by the EGD agenda. Such a dynamic might not be present in other policy areas. Nevertheless, given the considerable variation in the politicization of the specific issues discussed under the EGD, there is room for generalizing the findings. Furthermore, our assessments of agenda-setting influence are somewhat simplistic, and we assume different policy process stages remain distinct. Therefore, promising pathways for further research include assessing how groups affect changes in agenda status over time and examining the interplay between different policy stages. Finally, subsequent research should further weigh the influence of interest groups in shaping the agenda against the control exerted by other stakeholders in the policy process, such as political parties or the broader citizenry. While our analysis accounted for perceived support or opposition from key EU stakeholders, these assessments remain inherently subjective. Amid these promising directions for future research, our study has shed light on how information about audience support is often vital for gaining agenda-setting influence. Additionally, it highlights how salience and interest mobilization can mitigate biases that favor groups providing resource-intensive expert information.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773924000043

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Bursens, Dirk De Bièvre, Stefaan Walgrave, Iskander de Bruycker, Bastiaan Redert, and Adrià Albareda for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Emily Goris, Stefan Zagers, and Wout Donné offered helpful research assistance. Without the many respondents who were willing to be interviewed, this research would not have been possible. Finally, we are grateful for the constructive feedback of the EPSR editors and the anonymous reviewers.

Competing interests

The author declares none.