Introduction

Does lifestyle politics alienate people from other forms of political participation or rather lead people to do more activities? This paper aims to add empirical rigour to this longstanding debate about the consequences of a rise in lifestyle politics (Bennett, Reference Bennett1998; Micheletti and Stolle, Reference Micheletti, Stolle, Micheletti and McFarland2010; Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013). Specifically, it offers the first longitudinal analysis to test the ‘crowding out’ hypothesis which suggests that when people start engaging in politics through their lifestyle and consumption, they will abandon other, arguably more important types of political participation (Rössel and Schenk, Reference Rössel and Schenk2017; van Deth, Reference van Deth, Fisher, Fieldhouse, Franklin, Gibson, Cantijoch and Wlezien2018). We test whether engagement in lifestyle politics indeed leads away from other modes of political participation, or rather to them, as others have suggested (e.g. Willis and Schor, Reference Willis and Schor2012). We refer to these opposing ideas as the ‘gateway’ (to) and ‘getaway’ (from) hypotheses.

Both sides of the debate have presented opposing arguments. Authors advancing the getaway hypothesis (e.g. Berglund and Matti, Reference Berglund and Matti2006; Szasz, Reference Szasz2007; Wejryd, Reference Wejryd2018) argue that lifestyle politics (1) reduces the resources available for other forms of participation; (2) makes lifestyle activists feel they have ‘done enough’; and (3) takes place in lifestyle movement organizations (LMOs) that insulate participants from other modes of participation. In direct contrast, proponents of the gateway hypothesis (e.g. Gotlieb and Wells, Reference Gotlieb and Wells2012; Willis and Schor, Reference Willis and Schor2012; Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Engman and Johnston2015) argue that (1) people do not have a predefined amount of participatory resources available; (2) lifestyle politics can boost motivations to engage in politics more generally; and (3) LMOs offer opportunities to lifestyle activists to become more generally engaged. Evidence from case studies and experiments supports claims on both sides of the debate but tells little about patterns of behaviour in a more general population. Survey research has remained cross-sectional and is therefore limited in explaining changes over time.

The current paper provides the first quantitative, large-N, longitudinal test of the gateway/getaway hypotheses, and their underlying causal assumptions, using original data from a panel study of 1538 politically active individuals from the Flemish region of Belgium (2017–18, using the ‘UA Citizens Panel’). With detailed repeated observations on various forms of political participation, we are able to test the relationship between lifestyle politics and institutionalized and non-institutionalized political participation over time. Our findings mainly indicate positive associations with both these modes of participation, thereby lending support to the gateway hypothesis. This relationship appears to come about mainly as lifestyle politics increases participants’ political concerns.

The contested significance of lifestyle politics

Lifestyle politics refers to ‘the politicization of everyday life choices, including ethically, morally or politically inspired decisions about, for example, consumption, transportation or modes of living’ (de Moor, Reference de Moor2017, p. 181). In other words, it refers to the way in which citizens use their lifestyle choices to engage in politics (Giddens, Reference Giddens1991; Jones, Reference Jones2002; Micheletti and Stolle, Reference Micheletti, Stolle, Micheletti and McFarland2010). As such, lifestyle politics relates closely to political consumerism – in particular buycotts, or the politically motivated purchase of certain products (Copeland, Reference Copeland2014). While some see lifestyle politics as a more holistic version of political consumerism (Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013), we follow interpretations that see political consumerism as one element of a politicized lifestyle (de Moor, Reference de Moor2017). Comparative data are mainly available on political consumerism and show that lifestyle politics is on the rise (Koos, Reference Koos2012; Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013). In many Western European countries, more than half the population makes consumer choices on the basis of political, ethical, or environmental considerations (de Moor and Balsiger, Reference de Moor, Balsiger, Boström, Micheletti and Oosterveer2019).

Even though lifestyle politics is seen as increasingly important, they have been a part of Western political participation repertoires since at least the emergence of new social movements from the late 60s onward (Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013). New social movements put emphasis on the importance of everyday life and generated some of the first communes in which people began to experiment with alternative forms of living (Melucci, Reference Melucci1996). Ever since, many new social movements have addressed issues through lifestyle politics. Feminists have, for instance, long argued that the personal is political, and through the fair-trade movement, social justice questions have been prominent in political consumerism (Boström et al., Reference Boström, Micheletti and Oosterveer2019).

Perhaps most of all, lifestyle politics has been used to address environmental concerns. Various literatures, including those on political consumerism, green citizenship, new materialism, and pro-environmental behaviour, put strong emphasis on the way in which citizens (can) address environmental challenges through everyday behaviours (Micheletti, Reference Micheletti2003; Jackson, Reference Jackson2005; Dobson, Reference Dobson2007; Whitmarsh and O’Neill, Reference Whitmarsh and O’Neill2010; Schlosberg and Craven, Reference Schlosberg and Craven2019). They describe how environmental considerations inspire ethical shopping behaviour, vegan or vegetarian lifestyles, efforts to save energy, changes to more sustainable modes of transportation, and individual or collective projects to start producing one’s own energy or food.

What this rise in lifestyle politics means for political participation more broadly remains unclear and hotly debated (Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013; Boström et al., Reference Boström, Micheletti and Oosterveer2019). Political participation has been defined in various ways but is generally seen as voluntary activities by citizens intended to influence ‘the collective life of the polity’ (Macedo, Reference Macedo2005). Accordingly, lifestyle politics can be classified as a mode of political participation, but it stands apart from other modes of participation that focus on influencing political decision-making processes (van Deth, Reference van Deth2014; de Moor, Reference de Moor2017). Specifically, both institutionalized and non-institutionalized modes of participation voice opinions to influence political decisions using, respectively, official channels like political parties or unofficial ones like demonstrations (Theocharis and van Deth, Reference Theocharis and van Deth2018). By contrast, lifestyle politics typically does not engage with, or is even seen as an exit from, the democratic system (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970; Rapp and Ackermann, Reference Rapp and Ackermann2016).Footnote 1

Based on this difference, there is both enthusiasm and scepticism about the rise of lifestyle politics. On the one hand, there is a sense of optimism about the fact that citizens are exploring new arenas to engage in politics, including the arena of everyday life (Lichterman, Reference Lichterman1995; Bennett, Reference Bennett1998, Reference Bennett2012; Amnå and Ekman, Reference Amnå and Ekman2014). As such, lifestyle politics is, for instance, seen as compensation for a decrease in electoral participation (Dalton, Reference Dalton2008; van Deth, Reference van Deth, Fisher, Fieldhouse, Franklin, Gibson, Cantijoch and Wlezien2018). Citizens are not becoming passive. They are rather exploring new ways of being active that, following the notion of sub-politics (Beck, Reference Beck1997), is seen as particularly timely (Schlosberg and Craven, Reference Schlosberg and Craven2019). As governments appear unable to address main environmental challenges, individuals step in with ‘do-it-yourself’ lifestyle politics (de Moor et al., Reference de Moor, Marien and Hooghe2017).

On the other hand, many argue that lifestyle politics alone does not constitute full democratic engagement and question whether in itself it is an effective means to social change. Few scholars believe lifestyle politics can be the sole solution to society’s main problems (Lekakis, Reference Lekakis2013; Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013). Lifestyle politics is sometimes seen as ineffective (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Krahn and Krogman2013), in particular considering issues of scale (Seyfang, Reference Seyfang2009). Neither does it constitute full democratic engagement as it does not involve participation in collective decision-making at a societal level, nor does it fulfil other key democratic values (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Wejryd, Reference Wejryd2018). If citizens were to collectively exit from engaging with the state, instead addressing societal problems through the arena of everyday life, this could lead to a serious democratic deficit (Maniates, Reference Maniates2001).

The gateway/getaway debate

These concerns have fostered a strong interest in how lifestyle politics relates to voice-oriented, institutional, and non-institutional modes of political participation (for an overview see Rössel and Schenk, Reference Rössel and Schenk2017; Wejryd, Reference Wejryd2018). Sceptics believe that those who engage in lifestyle politics will become less likely to engage in other types of political participation. For instance, according to Szasz, ‘rather than inspiring additional action, ethical consumption is more likely to silence the internal voice that urges us to do more’ (Reference Szasz2007, p. 79). As such, lifestyle politics is seen to represent and serve a neoliberal ideology of individualization that reduces citizens to consumers by commercializing political activism (Maniates, Reference Maniates2001; Berglund and Matti, Reference Berglund and Matti2006; Blühdorn, Reference Blühdorn2017). According to Jensen (Reference Jensen2009): ‘Consumer culture and the capitalist mindset have taught us to substitute acts of personal consumption (…) for organized political resistance’. Instead of tackling systemic flaws, lifestyle politics is seen to merely provide ‘alternative options’ and the simulation of politics (Blühdorn, Reference Blühdorn2017).

Others qualify this critique by stressing that lifestyle politics makes citizens overall more active (Gotlieb and Wells, Reference Gotlieb and Wells2012; Willis and Schor, Reference Willis and Schor2012; Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Engman and Johnston2015). They suggest that lifestyle politics is a gateway to, rather than a getaway from, other types of political participation. Precisely because lifestyle politics is such a ‘light’ form of engagement (for instance, they do not require one to face the effort and potential risks of going to a demonstration or large investments of time in electoral campaigns), they generate low threshold entry points for people to become politically active, in turn opening pathways towards more extended political engagement (Zukin et al., Reference Zukin, Keeter, Andolina, Jenkins and Carpini2006).

Case studies have demonstrated that gateway and getaway mechanisms both occur, but due to their small-N nature, they cannot identify which trend is most common (in support of gateway, see for instance Dubuisson-Quellier et al., Reference Dubuisson-Quellier, Lamine and Le Velly2011; de Moor et al., Reference de Moor, Marien and Hooghe2017; in support of getaway, see for instance de Moor et al., Reference de Moor, Catney and Doherty2019; Kenis, Reference Kenis2016). Authors have therefore sought to settle the debate by using cross-sectional surveys on political participation (Gotlieb and Wells, Reference Gotlieb and Wells2012; Willis and Schor, Reference Willis and Schor2012; Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013). These surveys typically indicate a gateway effect by showing positive correlations between political consumerism and other forms of political participation. However, it is premature to draw strong conclusions based on such cross-sectional data. In particular, we cannot make claims about causality or sequence based on cross-sectional correlations. Positive or negative correlations in cross-sectional data merely indicate the coexistence of two variables at one time, whereas testing the gateway/getaway hypothesis clearly requires a longitudinal research design that analyses the sequential order of behaviour (cf. Quintelier and van Deth, Reference Quintelier and van Deth2014).

Thus, to address this gap in the literature, we use longitudinal data to test the following getaway and gateway hypotheses, respectively:

The more people participate in lifestyle politics at T1, the less they will participate in other modes of political participation at T2. (H1a)

The more people participate in lifestyle politics at T1, the more they will participate in other modes of political participation at T2. (H1b)

These hypotheses will be tested for institutionalized as well as non-institutionalized participation as both have been contrasted to lifestyle politics as voice-oriented modes of participation. However, non-institutionalized participation and lifestyle politics both operate outside institutional politics, and compared to institutional participation, both reverse gender and age inequalities (Marien et al., Reference Marien, Hooghe and Quintelier2010). Hence, the relation between non-institutionalized participation and lifestyle politics will presumably be more pronounced than between institutionalized participation and lifestyle politics.

Causal mechanisms

In this study, we improve upon previous work by using panel data instead of cross-sectional survey data. However, even though panel data can show correlations over time, the fact remains that ‘correlation is not causation’. Experimental research is more capable at demonstrating causality but is limited in operationalizing political behaviour as a ‘treatment’ applied to randomized groups – at least if we want to explain actual rather than hypothetical behaviour (Wejryd, Reference Wejryd2018). Therefore, as a further step towards understanding the effect of lifestyle politics, we analyse the mechanisms by which getaway and gateway effects are, implicitly or explicitly, assumed to come about.

Resources

Proponents of the getaway hypothesis refer to the ‘civic voluntarism model’ of political participation (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady2012) to argue that resources invested in lifestyle politics (e.g. time or money) cannot be spent on other activities (Johnston and Szabo, Reference Johnston and Szabo2011). There may therefore be a zero-sum relation, or at least ‘tactical competition’ between lifestyle politics and other types of political participation (Maniates, Reference Maniates2001; Balsiger, Reference Balsiger, Bosi, Giugni and Uba2016; van Deth, Reference van Deth, Fisher, Fieldhouse, Franklin, Gibson, Cantijoch and Wlezien2018). Various forms of lifestyle politics bring with them considerable financial costs (e.g. retrofitting one’s house to reduce environmental impacts), as well as time and effort (e.g. producing one’s own food). But even the most basic forms of political consumerism can over-burden citizens because of the information required to organize one’s entire lifestyle around political principles (Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013). Thus, even though buying fair-trade coffee or organic apples may not compete with someone’s availability to protest, more encompassing lifestyle politics may. Considering that especially the most intensive and extensive forms of lifestyle politics may be in tactical competition over resources with other modes of participation, we should expect the getaway effect to be strongest among the most dedicated lifestyle activists:

The getaway effect is strongest among people who engage in lifestyle politics most extensively. (H2a)

Yet while extensive engagement in lifestyle politics may indicate some resource depletion, it may also indicate greater levels of commitment and thus a greater overall availability of participatory resources (Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013). Concurrently, although highly engaged lifestyle activists may already have spent more participatory resources, the underlying motivation that drives them makes that they have more participatory resources available overall, suggesting that in fact:

The gateway effect is strongest among people who engage in lifestyle politics most extensively. (H2b)

Motivations

Implied in these discussions about resources are also claims about motivations. Motivations are key predictors of political participation (Klandermans, Reference Klandermans, Snow, Kriesi and Soule2004), and they are likewise considered to be an important part of the mechanisms linking lifestyle politics and other modes of political participation (Willis and Schor, Reference Willis and Schor2012). Yet again we find competing claims underlying the gateway and getaway hypotheses.

Promonents of the getaway hypothesis primarily point out that participation in lifestyle politics will reduce motivations to participate otherwise through a process of ‘moral licencing’ (Szasz, Reference Szasz2007; Mazar and Zhong, Reference Mazar and Zhong2010). It is assumed that people will feel that their act of lifestyle politics means they have done enough. The presumed mechanism goes something like this: A person sees societal problems around them, changes something in their lifestyle that they feel addresses the issue, making them feel they have taken responsibility, and by extension, reducing their inclination to act otherwise. We can test two assumptions at the heart of this reasoning.

First, citizens who perceive lifestyle politics as very effective will be more likely to opt out of other forms of participation, because the feeling of effectiveness likely informs a feeling of having done enough (e.g. Maniates, Reference Maniates2001). By contrast, someone who does lifestyle politics without believing that this will change much (doing it instead for deontological reasons) will not feel they have done enough and should not be drawn away from other modes of participation. Thus:

The getaway effect is stronger among people who perceive their lifestyle politics to be more effective. (H3a)

Second, citizens who engage in lifestyle politics may feel less worried about the main issues associated with that mode of participation, because they have done something about it. In turn, reduced concerns should reduce motivation for, and engagement in, other modes of participation. We therefore hypothesize the following path:

The more people engage in lifestyle politics, the less concerned they become about the issues associated with that engagement, and the less they will engage in other modes of participation. (H4a)

Yet in support of the gateway hypothesis, efficacy and political concerns could also have the opposite effect. Some research shows that efficacy of one mode of participation can be positively related to the perceived effectiveness of others – either because both stem from an underlying general sense of internal efficacy, or because confidence in one area may spill over into others (Morrell, Reference Morrell2005; de Moor, Reference de Moor2016). Following this reasoning, it can be expected that:

The gateway effect is stronger among people who perceive their lifestyle politics to be more effective. (H3b)

Moreover, it can be argued that through lifestyle politics people will actually become more aware of the urgency and complexity of problems like environmental degradation, thus motivating them to become engaged in other types of participation as well (Lorenzen, Reference Lorenzen2012). The resulting expectation is that:

The more people engage in lifestyle politics, the more concerned they become about the issues associated with that engagement, and the more they will engage in other modes of participation. (H4b)

Organizational context

Through recruitment and the provision of participation opportunities, social movement organizations play a key role in the political activation of citizens (Klandermans, Reference Klandermans, Snow, Kriesi and Soule2004). Therefore, a final set of expectations focuses on the mobilizing role performed by LMOs (Haenfler et al., Reference Haenfler, Johnson and Jones2012). It has been found that some LMOs, such as Transition Towns (the most prominent and most studied example in the field), reject ‘negative’ types of political participation, such as protesting (Chatterton and Cutler, Reference Chatterton and Cutler2008; Kenis, Reference Kenis2016). These LMOs prefer to focus exclusively on providing ‘pleasurable, convivial and pragmatic’ activities, believing that they can thereby attract the greatest number of participants and maximize their impact (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Johnston and Parkins2017). Of course, not all LMOs share this view, but even those that seek to combine the promotion of alternative lifestyles with oppositional actions experience that doing so can be difficult in practice (de Moor et al., Reference de Moor, Catney and Doherty2019). It can therefore be expected that those who engage in lifestyle politics collectively will embed themselves in organizational contexts that hinder engagement in other modes of participation:

The getaway effect is stronger among people who engage in lifestyle politics as part of a collective. (H5a)

Yet proponents of the gateway hypothesis point out that LMOs in practice rarely reject opposition in any absolute terms (Urry, Reference Urry2011; Schlosberg and Craven, Reference Schlosberg and Craven2019). Case studies describe how some LMOs combine lifestyle politics, protesting and campaigning (for an overview see de Moor, Reference de Moor2017). Indeed, the very fact that these groups choose to engage in lifestyle politics collectively is interpreted as a rejection of a highly individualized notion of citizenship and may in fact bolster engagement in other modes of collective action, like protesting. From this reasoning flows the expectation that:

The gateway effect is stronger among people who engage in lifestyle politics as part of a collective. (H5b)

Data

Most political participation studies use general population surveys to analyse why some people participate in politics while others do not. By contrast, the crowding out debate primarily focuses on the politically active part of the population. That is, the getaway hypothesis addresses why some people engaged in (non-)institutional participation stop or reduce their engagement. The gateway hypothesis considers the reverse process by asking what leads people to become more engaged, comparing people on the basis of varying levels of lifestyle politics. The latter comparison could of course include people who are entirely politically inactive to see whether they have a greater or smaller propensity to become engaged in (non-)institutionalized participation than people already involved in lifestyle politics. However, people who go from politically inactive to active over the course of a 1-year panel study will likely be too rare for statistical purposes. More importantly, including sufficient numbers of politically active and inactive citizens through a panel survey of the general population would be extremely costly (van Stekelenburg et al., Reference van Stekelenburg, Walgrave, Klandermans and Verhulst2012). Thus, notwithstanding the usefulness of testing the gateway hypothesis in the general population, we opt for a convenience sample of politically active individuals, while ensuring a sufficiently large sample to include the diversity representative of the politically active part of the population in our study.

We use data from the UA Citizens Panel of the University of Antwerp.Footnote 2 This panel consists of individuals who were primarily recruited through a voting advice application that is widely used in the Flemish part of Belgium. As voting is mandatory in Belgium, voters are almost representative of the general population. Yet people who use voting advice applications have above average interest in politics and will also consequently be more politically active (Rosema et al., Reference Rosema, Anderson and Walgrave2014). The UA Citizens Panel therefore provides an ideal sample to investigate changes in political participation repertoires.

We interviewed the members of the panel twice using an online questionnaire (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah and Seattle, Washington, US), keeping question wording, layout, and survey mode the same between waves to prevent survey design biases. In 2017, the survey yielded 2292 interviews. This gave us a response rate of 31%, which can be considered solid for online surveys (cf. Sheehan, Reference Sheehan2006; Saleh and Bista, Reference Saleh and Bista2017).Footnote 3 From this group, 1628 respondents participated in the interview again in 2018, while 98 individuals left the panel before the second survey wave started. Hence, we reached a response rate of 74% between survey waves.Footnote 4

The data confirm that the UA Citizens Panel provides a sample of people who are almost all interested or very interested in politics and are politically active.Footnote 5 We discarded those respondents who did not answer any of our political participation questions (N = 90). Except for two individuals, all remaining respondents (N = 1538) had engaged in at least one form of political participation in the 12 months prior to the interview. Our sample appears to be fairly representative of the politically active part of the general population in Flanders. The PartiRep 2014 study covers a representative sample of the Flemish population (weights for age, gender, and province of residence are used to compensate for deviations of the sample) and shows that the high average levels of education and political interest in our data are also observed in the politically active sub-sample of the Flemish population (see Appendix A). Compared to the PartiRep data, women and young people are underrepresented in our sample, but our sample size ensures sufficient statistical power to test our hypotheses while controlling for these biases.

Even though key political participation predictors have thus been accounted for, generalizations still need to be made with caution. It cannot be ruled out that our sample differs from the politically active Flemish population in a way not measured in our survey. Furthermore, in terms of generalizability, it must be recognized that our data come from only one country. However, Belgium has been defined as a fairly typical European case in terms of political attitudes and participation (Quaranta, Reference Quaranta2013; Hooghe and Marien, Reference Hooghe and Marien2014; de Moor et al., Reference de Moor, Marien and Hooghe2017) and thus offers an ideal case for a first test of the gateway/getaway hypotheses that future studies can expand upon.

Measures

Main dependent and independent variables

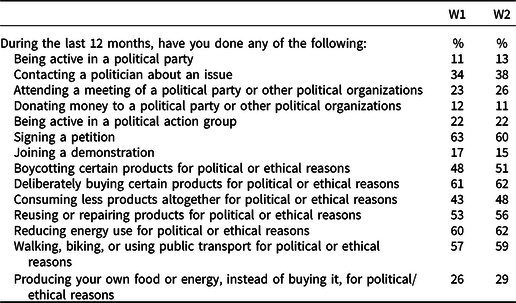

Our data are not only unique in providing longitudinal measures of political participation. They are also uniquely detailed. We asked respondents about their engagement in several forms of political participation in the past 12 months: four linked to institutionalized participation, three to non-institutionalized participation, and seven linked to lifestyle politics. Levels of participation in both survey waves were fairly high and comparable between waves 1 (2017) and 2 (2018) (see Table 1). Though relevant for institutionalized participation as well, we cannot look at voting. Because voting is mandatory in Belgium, there is insufficient variation on this variable (98% of the sample voted in the last election).

Table 1. Political participation

Source: UA Citizens Panel.

Note: N = 1538.

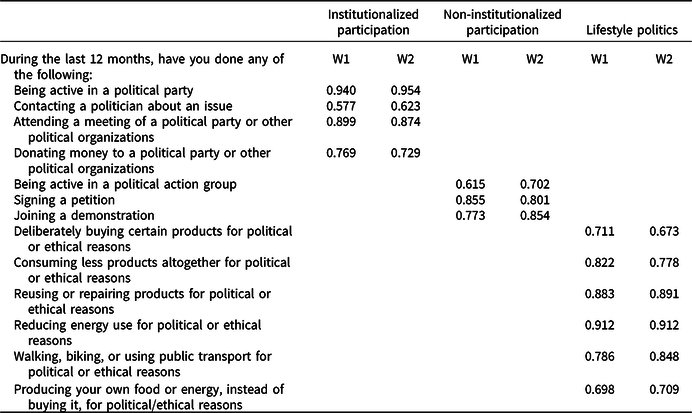

To assess whether these forms of participation indeed relate to these underlying modes of participation, we use Principal Component Factor (PCF) analysis with Kaiser normalized oblique rotation (oblimin in Stata 15, StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA). Oblique rotation is applied because we do not assume factors to be related orthogonally. Indeed, while various modes of participation might be distinguishable, they are likely still positively correlated (cf. Theocharis and van Deth, Reference Theocharis and van Deth2018). A first iteration of the PCF (see Appendix B) indicates that boycotting loads mainly on a separate fourth factor in the first wave and on both non-institutionalized participation and lifestyle politics in the second wave. This ambiguity makes theoretical sense because boycotting conceptually falls between these two modes of participation. It is a lifestyle act that is intended as a form of protest (Copeland, Reference Copeland2014). We find a similar pattern for buycotting, though in line with our expectations, it loads more clearly on the factor measuring lifestyle politics. We therefore recalculate the PCF with the exclusion of boycotting. Without this item, the results (Table 2) clearly reflect established notions of what constitutes lifestyle politics, institutionalized, and non-institutionalized participation (cf. Baringhorst, Reference Baringhorst2015; Theocharis and van Deth, Reference Theocharis and van Deth2018). As it is our aim to compare participation levels and their relationships measured at different points in time by composite scales, we tested for measurement invariance between the two survey waves (Taris, Reference Taris2000; Brown, Reference Brown2006). The analysis shows strong factor invariance, which implies that the relationship between the survey items and the three latent constructs is comparable between the two survey waves.Footnote 6 This allows for cross-wave comparisons and analyses as was set out to do in our panel analysis (Widaman and Reise, Reference Widaman, Reise, Bryant, Windle and West1997).

Table 2. Factor analysis political participation

Source: UA Citizens Panel.

Notes: N Wave 1 (W1) = 1536, N Wave 2 (W2) = 1493. Principal Component Factor Analysis, Oblimin Rotation, 0.400 cut-off point.

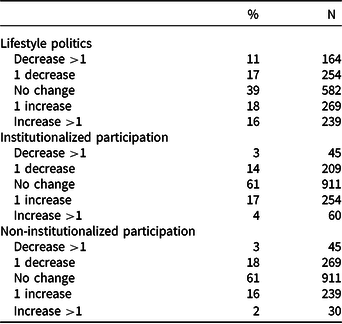

The three measures of modes of political participation are constructed as sum scales in which individuals get +1 for each mode of participation they have reportedly done in the past 12 months. This results in scales running from 0 to 6 for lifestyle politics, 0 to 4 for institutionalized participation, and 0 to 3 for non-institutionalized participation. Table 3 presents a comparison between 2017 and 2018 for the reported participation levels for each type of political participation. For all types of participation, we observe a substantial proportion of respondents remaining at the same level of engagement, which, compared to previous studies, is unsurprising (Quintelier and van Deth, Reference Quintelier and van Deth2014). Yet, the proportion increasing or decreasing their engagement in a certain mode of participation is substantial as well. For lifestyle politics and institutionalized participation, the proportion of respondents reporting an increase is larger than the proportion of respondents reporting a decrease. For non-institutionalized participation, more respondents report a decrease than an increase. Finally, the table shows that the proportion of respondents that made a larger change in participation (displayed as participating in more than one additional or fewer activities in 2018 compared to 2017) is limited. Overall, these figures indicate that while political participation is seen as reflecting longer term patterns of political engagement, a 1-year interval is sufficiently large to observe changes in participation patterns.

Table 3. Change in political participation 2017–2018

Source: UA Citizens Panel.

Notes: N = 1493. The fact that our measure for lifestyle politics ranges from 0 to 6, while institutionalized participation ranges from 0 to 4 and non-institutionalized participation ranges from 0 to 3 and, explains the broader spread of change in lifestyle politics. When rescaling all types of participation to range from 0 to 1, the spread of lifestyle politics proves to be similar to that of (non-)institutionalized participation (see Appendix C).

Control variables

We control for several indicators that are well known to relate to political participation and that are therefore likely relevant in analysing changes in participation as well. These include basic socio-demographic characteristics, such as age, sex, income, and levels of education (which is measured by the question at what age respondents stopped studying full time), as well as several political attitudes, including political interest, satisfaction with democracy, institutional trust, internal efficacy, and external efficacy (Vráblíková, Reference Vráblíková2014). These attitudes are measured using conventional measures and are turned into sum scales following PCF analysis when measured by multiple survey items (cf. Niemi et al., Reference Niemi, Craig and Mattei1991; Vráblíková, Reference Vráblíková2014; Braun and Hutter, Reference Braun and Hutter2016). The details of all variables, including averages and standard deviations, and the factor analyses are in Appendix C.

Analyses

The overall aim of our analysis is to test whether lifestyle politics in 2017 is related to decreases or increases in institutionalized and non-institutionalized participation in 2018. To assess such changes in participation requires a model that measures changes in political participation over time, or more precisely, that explains differences between scores on political participation in T1 and T2.

The simplest way to model change in participation is directly taking the difference between scores in T1 and T2 as dependent variable, also known as an unconditional change model. However, such a model assumes that changes in participation are uncorrelated to the reported level of participation in T1 (Finkel, Reference Finkel1995; Berrington et al., Reference Berrington, Smith and Sturgis2006). However, because of the ‘regression to the mean’ effect, responses in T1 are frequently negatively correlated with change. Respondents who scored high at first have the tendency to score lower later on, because there is simply less room to increase one’s score on the response scale (Taris, Reference Taris2000). The opposite is the case for respondents with an initially low score. Applied to our study, this means that the higher the level of (non-)institutionalized participation in 2017 is, the lower the potential for growth in 2018.

To solve this problem, we use a conditional change ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model that takes scores at T2 as dependent variable but controls for scores in T1. The difference between the two scores becomes what the model explains, while accounting for the regression to the mean effects (for details and earlier applications of this model see Finkel, Reference Finkel1995; Taris, Reference Taris2000; Hooghe and Meeusen, Reference Hooghe and Meeusen2012). Hence, controlling for (non-)institutionalized participation in 2017 allows us to interpret the results as the relationship between the explanatory and control variables, and change in (non-)institutionalized participation.

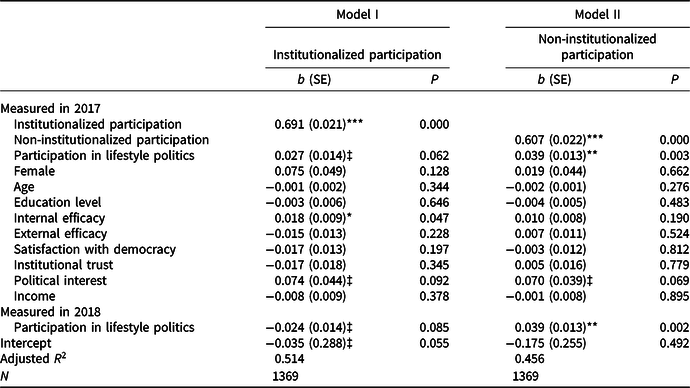

Table 4 presents the analyses that regress change in institutionalized participation (Model I) and non-institutionalized participation (Model II) against respondents’ participation in lifestyle politics. Model I suggests that increased engagement in institutionalized participation is marginally significantly (P = 0.062) positively associated with engagement in lifestyle politics in 2017. A 1-unit increase in lifestyle politics corresponds with a 0.027-unit increase in institutionalized participation between 2017 and 2018, controlling for institutionalized participation in 2017.Footnote 7 This provides some support for the gateway thesis (H1b). Furthermore, we also observe a marginally significant negative instantaneous effect (P = 0.085) of lifestyle politics on institutionalized participation. Hence, some weak support is observed for an instantaneous getaway effect.

Table 4. OLS regression of institutionalized and non-institutionalized participation (conditional change model)

Source: UA Citizens Panel.

Notes: ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ‡P < 0.10. The variance inflation factor suggests no multicollinearity problems.

The model explains a substantial part of the variation in institutionalized participation in 2018 (adjusted R 2 = 0.51). However, this is largely because of the stability effect, and the effect of lifestyle politics is rather small. Figure 1 shows the predicted levels of institutionalized participation in 2018 based on Model I (Table 4). Institutionalized participation in 2017 is included as a control variable. The difference between the points on the figure therefore represents changes in participation. The predicted level is 0.772 for respondents who did not engage in lifestyle politics in 2017 and 0.934 for respondents who engaged maximally in lifestyle politics in 2017. Hence, the maximal gateway effect is a change of 0.162 on the institutionalized participation scale ranging from 0 to 4.

Figure 1. Predicted levels of institutionalized participation in 2018 based on Model I.

Model II presents the same analysis for non-institutionalized participation. Increases in non-institutionalized participation are significantly positively related to participating in lifestyle politics in 2017. A 1-unit increase in lifestyle politics corresponds with a 0.039-unit increase in engagement in non-institutionalized participation between 2017 and 2018, controlling for non-institutionalized participation in 2017.Footnote 8 Next to this lagged effect that indicates a gateway effect, a statistically significant positive instantaneous relationship of 0.039 is observed between lifestyle politics and non-institutionalized participation as well.

We thus find support for the gateway thesis (H1b) instead of the getaway thesis (H1a). Again we explain a substantial part of the variation in non-institutionalized participation in 2018 (adjusted R 2 = 0.46; largely because of the stability effect), but effect sizes remain small. Figure 2 shows that the largest possible effect of lifestyle politics is a change of 0.232 on the non-institutionalized participation scale ranging from 0 to 3. Yet this is considerably larger than the effect on institutionalized participation. Moreover, considering that we are only looking at changes over 1 year, the effect could accumulate over longer periods.Footnote 9

Figure 2. Predicted levels of non-institutionalized participation in 2018 based on Model II.

Mechanisms

How do these effects come about? In this section, we inquire about several of the mechanisms implied in theoretical discussions, beginning with the role of resources, and then moving on to motivations and organizational context. Since we found the overall effect to be gateway, we focus on the latter.

According to hypothesis 2b, which considers the role of resources, it can be expected that people who engage extensively in lifestyle politics will demonstrate the greatest gateway effects. In other words, rather than expecting a linear effect, it is anticipated that for people with the highest scores on our lifestyle politics variables, the relationship between lifestyle politics and institutional and non-institutional participation should be stronger.Footnote 10 We test whether there is empirical support for this idea by estimating piecewise regression models testing whether the slope of the relationship between lifestyle politics and (non-)institutionalized participaton is significantly different for respondents who have the highest scores on the lifestyle politics variable (Stata, 1993; UCLA, 2019). The piecewise regressions in Table 5 show no significant change in the slope between respondents who have the highest score on lifestyle politics and the other respondents (Models III and V). Only in the case of non-institutionalized participation and when the breakpoint separates respondents with the two highest scores on lifestyle politics, the slope is significantly steeper (Model VI).

Table 5. Piecewise OLS regressions

Source: UA Citizens Panel.

Notes: Conditional change OLS regression models using mkspline in Stata 15. Standard errors in parentheses. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ‡P < 0.10. The coefficients represent the change in the slope from the preceding interval. It is indicated whether the change in the slope is significant, which would mean that the relationship between lifestyle politics (2017) and (non-)institutionalized participation changes after the break point.

The results thus show only limited support for H2b: the gateway effect regarding non-institutionalized participation is stronger for those most extensively engaged in lifestyle politics. If anything, this suggests that those who are strongly engaged in lifestyle politics might be more resourceful and committed to also engage in other non-institutionalized forms of political participation.

Next, we turn our gaze to two mechanisms that relate to the role of motivations. First, we test whether the gateway effect is stronger when people perceive of lifestyle politics as more effective (H3b). Each respondent was asked to rate on a scale from 0 to 10 whether they think each form of lifestyle politics that they said they engaged in is an effective way to exert influence. The variable ‘perceived effectiveness of lifestyle politics’ captures for every respondent the highest level of effectiveness they have attributed to at least with one type of lifestyle politics they engaged in. We introduce an interaction term between lifestyle politics and perceived effectiveness of lifestyle politics to our overall model used to test H1. The models in Appendix D show only one small, marginally significant interaction effect (P = 0.094): the gateway effect on non-institutionalized participation is stronger (0.005) for those who perceive of lifestyle politics as more effective. For institutionalized participation, we observe no significant interaction effect. Overall, we thus find only marginal support for the role of perceived effectiveness, indicating that perceived effectiveness for lifestyle politics reflects an underlying sense of political efficacy, or spills over into, and motivates other modes of participation.

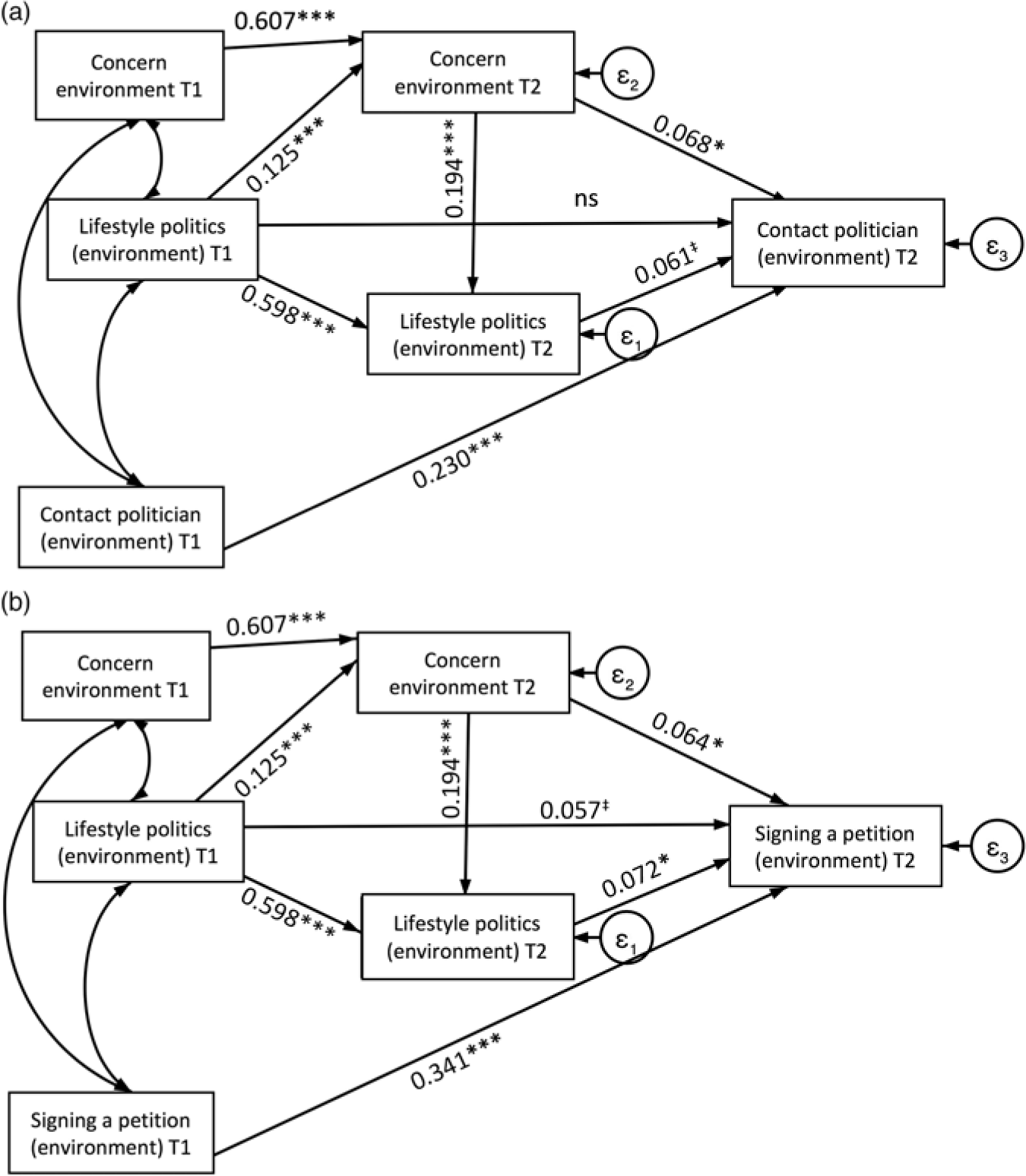

Second, we hypothesized that the relationship between lifestyle politics and (non-)institutionalized participation is not a direct relationship but runs through changes in concern about the issues that motivate participation as a result of engaging in lifestyle politics. This mediation of the gateway effect (H4b) is best modelled using path analysis, which allows us to test the significance of specific pathways. We calculate a structural equation model in Stata 15 (Acock, Reference Acock2013), using largely the same variables as in our main models (I and II in Table 4). However, to test these hypotheses, we must analyse political participation motivated by specific topics. The environment is one of the key topics of concern for political activists today and, as discussed above, has particular relevance as regards lifestyle politics (Stolle and Micheletti, Reference Stolle and Micheletti2013). Thus, the models presented in Figures 3a and b include information on lifestyle politics and (non-)institutionalized political participation specifically for environmental reasons. For lifestyle politics, we can assume that consuming less, changing means of transportation, reducing energy use, recycling, and producing one’s own food or energy were done for environmental reasons. For buycotts, respondents were asked to specify the issue that drove their buycott. We also asked respondents to specify the main issue of concern for one form of institutionalized participation – contacting politicians – and one form of non-institutionalized participation – signing a petition. A sufficient amount of respondents are engaged in buycotting (32%), contacting politicians (9%), or signing a petition (12%) for environmental reasons to allow for meaningful analyses.

Figure 3. The effect of lifestyle politics and (non-)institutionalized political participation, as mediated by environmental concerns.

In line with H4b, the path models show that the more respondents engaged in lifestyle politics for environmental reasons in 2017, the more concerned they became with environmental issues in 2018 (while controlling for concern for environmental reasons in 2017). In turn, environmental concern in 2018 is positively related to signing petitions and contacting politicians for environmental reasons in 2018 (while controlling for signing petitions and contacting politicians for environmental reasons in 2017). The path models do not show a clear significant direct relationshipFootnote 11 between engaging in lifestyle politics for environmental reasons in 2017 and signing petitions or contacting politicians for environmental reasons in 2018, suggesting that increased environmental concern is the main mechanism behind the gateway effect. We observe similar relationships for concerns about human rights and racism: buycotting for this reason leads to increased concern about human rights and racism, in turn increasing one’s propensity to sign petitions on this topic. This model is reported in Appendix E.

We finally look at the impact of organizational context to see whether the gateway effect is stronger for individuals who do lifestyle politics as part of a collective (H5b). We can test this mechanism with our survey data, as respondents who indicated that they participated in lifestyle politics activities were asked for each activity whether they did this ‘as a member of a collective, or as part of an organized activity’. We categorize respondents in three categories: those who never did any lifestyle politics in 2017 (17%), those who did lifestyle politics, but never collectively (67%), and those who engaged in at least one lifestyle politics activity as part of a collective or an organized activity (16%). By introducing a nominal variable covering these three categories (using the category of only doing individual lifestyle politics as a reference category) and interacting this variable on the organizational context of lifestyle politics with participation in lifestyle politics in 2017 (i.e. the number of lifestyle activities), we test whether engagement in lifestyle politics is differently related to other types of participation for respondents who did so collectively. The results presented in Appendix F show that contrary to the hypothesis, the gateway effect is not significantly different for those who do lifestyle politics collectively and those who only do it individually.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper presents findings from the first longitudinal test of the gateway/getaway hypotheses about the link between lifestyle politics and other modes of political participation – specifically, institutionalized and non-institutionalized participation. While some assume that lifestyle politics functions as a gateway to other modes of participation, others suggest that it functions as a getaway from them.

We have tested these hypotheses using unique panel data and longitudinal analyses. Our findings largely support the gateway hypothesis. We find that the more people do lifestyle politics at one time, the more they will participate in other modes of participation later on. This is the case for both institutionalized and non-institutionalized participation, even though the effect is clearer for the latter. As suggested earlier, this clearer gateway effect may be facilitated by some stronger commonalities between lifestyle politics and non-institutionalized participation, such as that both operate outside political institutions and reverse gender and age inequalities inherent to institutional participation. Moreover, for non-institutionalized participation, we also observe a significant positive relationship with lifestyle politics in the second year, that is, an instantaneous gateway effect. By contrast, a marginally significant instantaneous getaway effect is observed for institutional participation. Further research is needed to interpret this deviating observation.

Considering the mechanisms by which these effects come about offers further support for, and understanding of, the gateway hypothesis. The role of motivations is most strongly supported by the data. Looking at environmentally motivated participation, we find that engaging in lifestyle politics over time increases one’s political concerns, which in turn increases engagement in both institutional and non-institutional forms of political participation. We observe a similar path for concerns about human rights and racism in the relation between buycotting and signing petitions. Some limited support is also observed for the role of resources as we find that the gateway effect regarding non-institutionalized participation is stronger for those most extensively engaged in lifestyle politics. We also find a marginally significant association suggesting that the gateway effect on non-institutionalized participation is stronger for those who perceive of lifestyle politics as more effective. We do not find support for expectations about the role of organizational context. In sum, lifestyle politics has a gateway effect on other modes of participation, as mediated by increased political concerns. The effect for non-institutional participation is clearest and stronger for those most engaged in lifestyle politics and who perceive lifestyle politics as effective.

While our analyses provide an important step towards addressing the gateway/getaway debate, more research is needed. Firstly, while panel data and the modelling of mechanisms provide important steps towards testing causal effects, we are still looking at correlations (over time) rather than causation. Our findings do lend support to the causal gateway hypothesis, but we cannot rule out that observed changes and relationships are (partially) the result of an omitted variable. For instance, it is possible that lifestyle politics and (non-)institutional participation are all expressions of an underlying individual trend towards increased political engagement in which lifestyle politics tends to come before the other modes of participation, but without constituting a direct causal relation. For this reason, experiments and case studies remain important.

Secondly, our data only cover (reported) behaviour over a period of 2 years. While our analyses show that this is a sufficiently long period to observe and explain some changes in participation behaviour, we can only speculate on trends in the longer run. Simply extrapolating our findings would suggest that the relatively small effects we find over a period of 1 year might become larger in the long run. Moreover, we may find that some of the marginally significant or non-significant effects in our models – which are mostly in support of the gateway thesis – become more outspoken. However, such extrapolations should only be made with great caution as long-term changes in political participation involve unaccounted factors as well. Most importantly, they involve biographical changes that greatly affect participation. For instance, getting children or a full-time job can greatly reduce one’s biographical availability, which may increase competition between various forms of participation, and changes in someone’s social network may affect exposure to participation opportunities (Schussman and Soule, Reference Schussman and Soule2005).

Thirdly, our sample draws on the Dutch-speaking population of Belgium. How the relations we find look like within other populations remains to be seen. As Quaranta (Reference Quaranta2013) shows, the structure of political participation differs between countries, and so the relation between lifestyle politics and other modes of participation may differ as well. In short, additional research is needed to test to what extent our findings hold across time and space. Moreover, our data allow us to assess developments in participation among a politically interested and active population. It remains to be seen what the patterns and mechanisms we find look like when politically active and inactive people are compared.

Despite some limitations, our findings have important implications for ongoing discussions about changing participation repertoires and the rise of lifestyle politics. Surely, critics may still believe that lifestyle politics in itself is not an effective strategy to tackle environmental or other societal problems, but the concern that lifestyle politics will replace arguably more effective forms of participation seems, at least at the individual level, unjustified. If anything, people who do lifestyle politics are more likely to engage in other forms of participation as well. The image of the individual who used to participate in ‘serious’ political campaigns but gave up because they could conveniently express views by buying organic bananas or changing light bulbs is not confirmed when looking beyond individual cases. Those who are concerned that the rise in lifestyle politics implies citizens’ exit from the democratic system may have to worry less as well. While lifestyle politics as such may not constitute a full democratic linkage, it largely leads people to use their democratic voice more through other forms of participation, rather than less.

Of course, our findings address one specific element of critical debates about lifestyle politics and should not be interpreted as a full dismissal of those debates. For one, the mass-consumption society is closely linked to ecological crises, and it remains valid to ask whether engagement that is rooted in mass consumption itself can be expected to generate the fundamental change many today claim is needed (Maniates, Reference Maniates2001; Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Richardson, Rockström, Cornell, Fetzer, Bennett, Biggs, Carpenter, de Vries, de Wit, Folke, Gerten, Heinke, Mace, Persson, Ramanathan, Reyers and Sörlin2015; Boström and Klintman, Reference Boström, Klintman, Boström, Micheletti and Oosterveer2019). Still, individual pathways of political participation are at the heart of these debates, and our findings indicate that the rise of lifestyle politics may actually be good news for participatory democracy.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000377

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Media, Movements and Politics (M2P) research group of the University of Antwerp for making their UA Citizens Panel available for this study. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers of European Political Science Review and the participants and discussants at the ECPR General Conference 2018 in Hamburg and at the Dreiländertagung 2019 in Zürich for their insightful feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. This paper was made possible in part by funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (ESRC: ES/M010163/1).