Introduction

In recent decades, changing social norms on gender relations and the family have caused profound transformations to the institution of marriage. Claims to spousal rights by same-sex couples that further challenged the organization of people’s rights and responsibilities in marriage on the basis of biology and gender (Coontz, Reference Coontz2004: 975) eventually culminated in the legalization of marriage equality in numerous Western countries. The enactment of same-sex marriage laws is an example of gradual institutional change through ‘displacement’, whereby a new institution is activated and introduced in competition with an existing one – that is, marriage as a valid contract exclusively between opposite-sex couples. As a growing number of people defect to the new institution, the support for the old institutional arrangement is gradually eroded and, ultimately, it is fully replaced (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005: 20; Waylen, Reference Waylen2014: 217).

Displacement entailing gender reform has been so far mostly studied as an abrupt and exogenous mode of change, which results from the sudden breakdown of existing rules and their replacement with new ones (Waylen, Reference Waylen2014: 218–219). Less is known about displacement as a gradual process driven by endogenous factors – that is, by the battle for power between change and status quo actors embedded in institutions (Van der Heijden, Reference Van der Heijden2010: 234). At the same time, limited scholarly attention has been paid to the ways in which actors may resist reform efforts to preserve institutional stability (Van der Heijden and Kuhlmann, Reference Van der Heijden and Kuhlmann2017: 550). By focusing on marriage equality bills in the American states, this study seeks to shed light on how societal actors can bring about or hinder the displacement of institutions depending on their strength and on the political setting wherein they operate. The multiple governance sites of the US, as well as the states’ exclusive legislative power over the institution of marriage (Vickers, Reference Vickers2010), allow to study the fate of attempts at institutional reform and to assess how actors strategize in different venues.

Multi-value Qualitative Comparative Analysis (mvQCA, henceforth), a technique that allows taking into account complex causation, is implemented to identify the constellations of conditions under which same-sex marriage bills were passed or defeated, once introduced in the state legislature. My findings indicate that the success or failure of attempts at institutional reform is crucially determined by actors’ resources to lobby on behalf of their preferred policy outcome and to persuade veto players with agenda-setting power that either the displacement or the preservation of the status quo is necessary. Moreover, as the inclusion of religious exemptions is the only necessary condition for marriage equality laws to be adopted, the results highlight how value-loaded policies – that is, the so-called ‘morality policies’ (Mooney, Reference Mooney2000) – can be subjected to negotiation and compromise, despite implying conflict over first principles.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. First, I discuss the literature on gradual institutional change and outline the conditions that I expect to play a role in legislative reform processes. I then present the data and method used in the empirical analysis, to which the empirical results follow. Lastly, I discuss the findings and conclude.

Marriage equality and gradual institutional change

Institutions can be defined as ‘the rules of the game’ (North, Reference North1990: 3) that are socially sanctioned and collectively enforced. They distribute rights and obligations among actors and determine which actions and behaviors are ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, thereby organizing society into predictable and reliable patterns (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005: 9). Marriage can be defined as an institution in that it still embodies the normative ideal for how sexuality, companionship, and procreation should be organized. Historically influenced by Christianity, marriage has been characterized as a heterosexual institution aimed at providing a stable, indissoluble basis for the nuclear family, with state policies regulating and promoting it as a way of living and providing unique rights, responsibilities, and obligations to those who enter a marital union (Calhoun, Reference Calhoun2000: 110). Accordingly, the institution of marriage can be regarded as a distributional instrument that gives advantages and power to specific actors, as well as disadvantages and subordination to others.

The power-distributional implications of institutions make them susceptible of being contested and of becoming an ‘arena of conflict’ (Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016: 5) between those who are losers in the existing institutional arrangement and those who benefit from the status quo (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010). Contestation of existing rules plays therefore a crucial role in institutional transformation: institutions are subject to change when their ideational foundation is shaken and people do not feel compelled to comply with them anymore (Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016). This is the case of marriage equality, which rose as a policy issue amidst a decline of religious control, as well as an increase in popularity of alternative family-building options that did not necessarily contemplate heterosexual marriage (Amato, Reference Amato2004).

This distributional perspective is in line with the literature on morality policies, which analyses contentious policies such as same-sex marriage in terms of redistribution of values. A distinctive trait of morality policies is that they concern basic values that people care deeply about (Mooney, Reference Mooney2000) and address ‘ultimate questions about societal organization’ (Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen, Reference Engeli, Green-Pedersen, Larsen, Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen2012: 23). Values not only constitute the source of individual preferences on specific policy outputs but they also represent an instrument of political and social power in so far as different actors may gain or lose power if certain beliefs prevail (Knill, Reference Knill2013: 312). In this sense, morality policies also create distinct winners and losers in values endorsed by the government, and opposing groups will compete to have their beliefs affirmed by a policy change (Meier, Reference Meier1999; Studlar and Burns, Reference Studlar and Burns2015).

Accordingly, marriage is also a matter of public policy, defined as an authoritative decision – that is, backed up by sanctions in case of noncompliance – by a government on behalf of its citizens to change or maintain the status quo, which can be expressed through laws or judicial rulings and typically affects every member of the polity (Howlett and Cashore, Reference Howlett, Cashore, Engeli and Rothmayr Allison2014: 17; Birkland, Reference Birkland2016: 7–8). A government’s decision to change the status quo and eliminate the gender specificity of the right to marry deeply transforms the institution of marriage by altering the way it organizes society, as well as the set of values it embodies. On the one hand, the adoption of marriage equality is part of those ‘politically generated “rules of the game” that directly help to shape the lives of citizens […] in modern societies’ (Pierson, Reference Pierson, Shapiro, Skowronek and Galvin2006: 115). It does so not only by extending to same-sex couples the unique rights, responsibilities, and obligations linked to marriage but also, and more fundamentally, by eliminating people’s sexual orientation as a legal basis for their exclusion from one of society’s core institutions, which has historically played a central role in their subordination as second-class citizens (Calhoun, Reference Calhoun2000: 108). On the other hand, the legalization of same-sex marriage constitutes a change of the values on which the institution of marriage is based. Indeed, it enshrines a more gender-egalitarian and secular definition of marriage as the recognition of a couple’s long-term commitment and the ideal environment for child-rearing, irrespective of sexual orientation. In this vein, it moves marriage away from a traditional view mainly articulated on the basis of religious beliefs and natural law accounts that exclusively afford legitimacy to those marital unions that result in procreation (Calhoun, Reference Calhoun2000: 110; Griffin, Reference Griffin2017: 8). In so far as this policy change governs actors’ interactions by determining their rights and obligations – which can be publicly enforced by appealing to third parties, such as judicial courts – as well as by stipulating which marital unions are socially deemed desirable, the legalization of same-sex marriage can be conceived of as an instance of institutional change (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005: 12; Pierson, Reference Pierson, Shapiro, Skowronek and Galvin2006: 116).

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT, henceforth) people have been historically disadvantaged by the definition of marriage as a heterosexual institution and have therefore a strong preference toward changing the status quo (Calhoun, Reference Calhoun2000: 108). In the United States, the LGBT movement took up the issue of marriage in response to social conservatives’ efforts to ban same-sex marriage. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, marriage equality opponents resorted to referenda to successfully enact state constitutional amendments that defined marriage exclusively as the union between a man and a woman. Through the adoption of these bans, social conservatives sought not only to prevent future attempts by the state legislatures and courts to legalize same-sex marriage but also to divert the LGBT movement’s agenda and resources. Indeed, during this period, LGBT activists had to spend time, money, and energy to counter their opponents’ campaigns instead of pursuing their own policy goals (Fetner, Reference Fetner2008). In 2003, however, the national bipartisan organization ‘Freedom to Marry’ was founded with the aim of uniquely advocating for marriage equality. Together with other civil rights and LGBT legal organizations, they spearheaded a centralized campaign and elaborated a strategic plan to win marriage equality nationwide called ‘Roadmap to Victory’. The strategy aimed at first displacing heterosexual marriage through major legislative reforms and judicial rulings in a critical mass of states, and subsequently winning marriage equality through litigation at the US Supreme Court. It specifically targeted those states where heterosexual marriage was less entrenched at the legal and societal levels (Wolfson, Reference Wolfson2017: 96–97 and 151–152). This meant, first, states where it was not embedded in the state constitution – that is, no constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage was in place. Second, states displaying high levels of public support for marriage equality, which spoke of the increasing discredit of heterosexual marriage in favor of a new version that was inclusive of all of sexual orientations.Footnote 1

While societal change actors, namely, the LGBT movement and its interest groups, initiated institutional reform in those states where the normative underpinnings of heterosexual marriage were most vulnerable to defection, defenders of the status quo actively sought to preserve institutional stability. In the case of marriage equality, societal status quo actors are conservative religious interest groups such as the Knights of Columbus, the National Organization for Marriage or Focus on the Family, as well as some Christian churches. Specifically, the Roman Catholic Church has played a predominant role as it has been historically strongly rooted in the majority of states in which legislation in favor of marriage equality has been proposed. Despite existing theological differences, it has not hesitated to ally with Protestant Evangelical and Black Protestant churches, as well as with the Mormon hierarchy in its fight against marriage equality (Cahill, Reference Cahill, Rimmerman and Wilcox2007; Campbell and Robinson, Reference Campbell, Robinson, Rimmerman and Wilcox2007). Insofar that churches represent particular subgroups in society (Warner, Reference Warner2000: 18), they can be regarded as strategic and calculating societal actors that lobby lawmakers on specific policies that concern them (Warner, Reference Warner2000; Fink, Reference Fink2009).

Change actors are likely to pursue the displacement of an institution when it does not afford opportunities for discretion in enforcement and/or interpretation (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010: 19). Even though marriage, as most institutions, might be ambiguous or open to interpretation (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010: 11) – that is, different views on what an institution means might coexist in each society – the way in which it is codified into law is not. In this sense, there is no discretion in enforcement: either marriage is a legally valid contract between two people, regardless of their sexual orientation, or it is not. Whether displacement is a successful strategy for achieving institutional change, crucially depends on change actors’ capacity to sustain mobilization over time. Indeed, the activation of a new institution and the defection from the old one by those actors that previously supported it may take years of political and social struggle. Displacement resulting in major legislative reform can therefore be a slow-moving process, during which both change and status quo actors are able to forge political alliances and take advantage of the reform and veto possibilities that the institutional setting and the political balance of power afford (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010; Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016).

For displacement to occur, key institutional veto players – that is, the governor and the state legislature, composed by the senate and the house – have to agree to change the status quo (Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2002: 37; Hacker, Reference Hacker2004: 245). Political parties determine the ideological distance, or congruence, between the governor and the state legislature. When controlled by the same party, the three institutional actors are close together (even though not identical) and congruence between them increases. On the contrary, cases of divided government indicate that one to two of the relevant institutional actors might have very different policy preferences (Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2002: 218). At the same time, political parties also offer important access points for societal actors to enter the political arena, control the legislative agenda, and influence the policy-making process. Politicians can then become key allies for change actors and defenders of the status quo alike (Fink, Reference Fink2009: 85). Indeed, elected officials in both the Democratic and the Republican Party are electorally incentivized to give voice to the interests of specific social groups and to promote policies near to their values (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). Societal actors are then able to affect policy to the extent that meeting their demands will result in better electoral prospects for politicians. The larger the electoral mobilization capacity and material resources – that is, campaign workers and money – churches and both LGBT and religious interest groups have, the more likely elected officials will be to champion their claims (Burstein and Linton, Reference Burstein and Linton2002: 386).

Since the 1990s, the Democratic and the Republican Parties have increasingly polarized around LGBT rights and same-sex marriage (Fetner, Reference Fetner2008). While gathering support from LGBT voters and social movements, Democrats have assumed the protection of marriage equality. Hence, when Democrats control the government, LGBT advocates have higher possibilities to place their issues on the legislative agenda and institutional veto players are more likely to agree to institutional change. LGBT legislators, who further increase the chances of marriage equality bills to be introduced in the state legislature, are also more likely to be Democratic (Haider-Markel, Reference Haider-Markel2010: 57). Conversely, conservative churches and religious movements have become key Republican constituencies, leading the Republican Party to gain a reputation for defending traditional values regarding sexuality and marriage (Fetner Reference Fetner2008). When Republicans control the government, status quo actors can gain access to the legislative agenda and effectively resist pressure for change by temporarily or permanently blocking the bill. Thus, even though reform actors manage to put institutional change on the agenda, the mobilization needed for the successful defection to the new institution is more difficult to sustain when the legislative agenda is controlled by defenders of the status quo (Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016: 17–18). Republican and divided governments also increase the chances to maintain institutional stability, as at least one institutional veto player is likely to disagree with reform.

As ‘points of strategic uncertainty where decisions may be overturned’ (Immergut, Reference Immergut1992: 27), veto referendums afford further opportunities for blocking institutional change. According to Fink (Reference Fink2009: 84), referendums are the most important veto point that churches may use, as these societal actors retain a high mobilization power. Referendums may also alter the behavior of legislators, who might prefer meeting the demands of those societal actors capable of launching a referendum, rather than facing electoral backlash if the legislation is defeated (Immergut, Reference Immergut1990: 404). Hence, limited access to popularly initiated legislative referendums that might repeal the newly enacted law enables institutional displacement.

Lastly, when institutional change occurs through political negotiation, the new institution is likely to be the result of compromise between actors with different policy goals (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005: 26). In the case of marriage equality, the inclusion of religious exemption clauses is the result of bargaining during the policy-making process (Wilson, Reference Wilson2014). Through these clauses, a wide range of religious individuals and organizations are protected from private lawsuits and government penalties for refusing to officiate same-sex marriages or offer their services to LGBT couples. Some states only afford First Amendment exemptions to the clergy from performing marriages that are against their faith. Other states, however, expressly protect the clergy from government penalty and private lawsuits and have extended the exemptions to religious institutions and not for profit, fraternal benefit societies and adoption agencies and social services (Wilson, Reference Wilson2014).Footnote 2 Given that heterosexual marriage is strongly associated not only with religion but also with religious liberties (Wilson and Kreis, Reference Wilson and Kreis2013), the new institution has to resonate with these values to garner public support and not be labeled as too ‘radical’ by political opponents (Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016: 12). Thus, while religious exemption clauses force change actors to adjust their goals to more conservative preferences, their inclusion may overcome the veto power of status quo actors and facilitate the defection to the new institution by conservative lawmakers and the electorate.

Data and methods

The empirical analysis includes 16 US statesFootnote 3 in the time period spanning from 2003, when Freedom to Marry was founded, to 2014, the year prior to the US Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which legalized marriage equality nationwide. Each observation corresponds to the state and year in which a bill in favor of marriage equality has been introduced in either the state house or the state senate. Once introduced, a bill has to undergo a long legislative process, during which it may be successfully adopted or defeated. The bill is first assigned to a legislative committee specialized on its subject matter that assesses it and decides whether to send it to the floor of the legislative chamber to be discussed and voted on. If it is approved on the floor of the legislative chamber in which it was introduced, the bill is sent to the second chamber to go through the same process. Once passed by the state legislature, the bill is sent to the governor, who can decide whether to sign it into law or veto it. In case of a veto, all the states under examination require a qualified majority in both chambers to override it.

The case selection follows Mahoney and Goertz’s (Reference Mahoney and Goertz2004) ‘possibility principle’, which maintains that only those cases in which the outcome of interest has a real possibility of occurring – not just a nonzero probability – should be included in the analysis. The cases in which the outcome is not possible are those states where bills in favor of same-sex marriage were never introduced in the state legislature. This case selection allows to make a distinction between policy failure and generalized status quo. Since the latter is constantly in place, it is almost impossible to identify specific cases and actors to analyze in order to explain its persistence. But when the status quo is challenged – that is, when a policy proposal reaches the legislative agenda and stands a fair chance of succeeding – then actors need to step forward to preserve institutional stability (Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg, Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2013: 286).

I employ mvQCA, a well-suited method for studying public policies comparatively (Rihoux, Rezsöhazy and Bol, Reference Rihoux, Rezsöhazy and Bol2011). This technique is rooted in the case-oriented theory of qualitative analysis that aims to systematically compare large populations. It does so by applying multivalent logic to set-theoretic relationships in order to identify, simplify, and compare combinations of conditions leading to a particular outcome (Thiem, Reference Thiem2015: 659). In mvQCA, theoretical concepts are operationalized as sets that are either dichotomous – for example, the set of states that legislated in favor of marriage equality – or represent multiple categories – for example, states with very strong LGBT interest groups, states with strong LGBT interest groups, and states with weak LGBT interest groups –. mvQCA allows for complex causality, which implies, first, that combinations of conditions lead states to enact same-sex marriage laws (conjunctural causation). Second, that there is more than one combination that can result in the adoption of marriage equality legislation (equifinality). Lastly, that different combinations of conditions may matter for same-sex marriage laws to pass than for them to fail (asymmetric causality) (Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 5–6). The strength of mvQCA with respect to the other two variants of QCA – that is, crisp-set QCA and fuzzy-set QCA – is that it can capture the extent to which a condition has to be present to produce the outcome, depending on the occurrence or absence of other conditions. This complex notion of causality implies that the impact of a condition on the outcome is determined by the context in which it takes place (Haesebrouck, Reference Haesebrouck2016). Hence, mvQCA is particularly useful for determining how far opposed actors need to mobilize in different political contexts, as well as in response to each other, in order to reach their preferred policy outcome.

mvQCA results are based on truth tables, which show all possible combinations of conditions and allow identifying necessary and sufficient conditions. The solution terms that result from the logical minimization of the truth table rows show all the possible ‘pathways’ to the outcome, as well as to the negation of the outcome. The logical operators AND (*) and OR (+) represent combinations and disjunctions of conditions, respectively. Results are evaluated by using parameters of fit. As a general rule, the more these parameters of fit approach one, the better. The consistency parameter shows the extent to which conditions are necessary or sufficient for the outcome, while coverage indicates how trivial the condition is for the outcome. The proportional reduction in inconsistency (PRI) shows the degree to which a causal pathway is not simultaneously sufficient for both the presence and absence of the outcome. The outcome and each condition have been operationalized and calibrated as follows:Footnote 4

Enactment of marriage equality laws (OUT)

The outcome is dichotomous, taking the value of 1 if marriage equality legislation has been enacted and 0 otherwise.

Strength of churches and religious interest groups (REL)

The more citizens and material resources that churches and religious interest groups are able to mobilize, the more they will be able to influence elected officials and therefore the legislative process (Burstein and Linton, Reference Burstein and Linton2002: 386). Following Fink (Reference Fink2009), I measure churches’ and religious interest groups’ mobilization potential by taking into account both the share of adherents in each state and their degree of religiosity. I calculate the share of adherents of four Christian religious traditions, following the RELTRAD typology (Woodberry et al., Reference Woodberry, Park, Kellstedt, Regnerus and Steensland2012): Roman Catholics, Evangelical Protestants, Historically Black Protestants, and Mormons. The level of religiosity has been measured as the share of adherents who attend religious service once a week or more. Church attendance allows both to take into consideration religious commitment among Christians (Mockabee, Monson and Grant, Reference Mockabee, Monson and Grant2001), as well as the impact that churches as civic associations might have on political mobilization (Jones-Correa and Leal, Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001). The share of adherents in each state is then weighted by the share of adherents that attend religious service once a week or more.

Another important variable to measure interest groups’ strength in a pluralist system, such the US, is the budget devoted to political contributions (Hoefer, Reference Hoefer1994: 174). I therefore track conservative religious interest groups’ contributions to the sitting governor and state legislature, for each state and year.Footnote 5 Additionally, I also look at the contributions to party committees and ballot measures committees in the year in which legislation in favor of marriage equality was introduced and the year prior to it. Summing together these measures, I obtain the percentage of conservative religious interest groups’ expenditures with respect to the total political contributions in each state and year.

Subsequently, I create a normalized index of churches and religious interest groups’ mobilization potential and another one of religious interest groups’ expenditures for each state and year.Footnote 6 By calculating the average of the two indexes, I obtain the raw data (RELindex) that is then calibrated into the three-valued condition REL (0 – weak churches and religious interest groups; 1 – strong churches and religious interest groups; 2 – very strong churches and religious interest groups). While no theoretical information exists as to what ‘strong interest groups’ or ‘strong churches’ exactly implies in numerical terms, an empirical examination of the data still allows to fix crossover points. These are anchored to large gaps in the RELindex, which indicate a significant qualitative difference between the cases (Hinterleitner, Sager and Thomann Reference Hinterleitner, Sager and Thomann2016: 10). Such significant gaps can be found between Hawaii in 2013 (0.211) and New York in 2011 (0.282) and between Maryland in 2008 (0.399) and Illinois in 2009 (0.453).

Strength of LGBT interest groups (LGBT)

To measure the political influence of LGBT interest groups at the state level, I follow Haider-Markel (Reference Haider-Markel2010) and first consider their mobilization potential by counting the share of same-sex unmarried partner households in each state. Subsequently, I collect data on LGBT interest groups’ political contributions following the same approach used for religious interest groups. I hence obtain the share of LGBT interest groups’ expenditures with respect to the total political contributions for each state and year.

I then create a normalized index of LGBT interest groups’ mobilization potential and another one of their expenditures for each state and year. To obtain the raw data (LGBTindex) underlying the three-valued condition LGBT (0 – weak LGBT interest groups; 1 – strong LGBT interest groups; 2 – very strong LGBT interest groups), I calculate the average of the two indexes. An examination of the LGBTindex shows that significant gaps in the data can be found between Illinois in 2012 (0.217) and Delaware in 2013 (0.274) and between Washington in 2012 (0.402) and Rhode Island in 2011 (0.494). Therefore, I set the crossover points at 0.246 and 0.448. These gaps are similarly positioned as the ones identified in the case of the RELindex, thus making the ‘weak’, ‘strong’, and ‘very strong’ categories in both the REL and LGBT conditions more comparable.

Promotion of the bill by the governor (GPROM)

This condition indicates whether the governor promoted the bill (1) – that is, the governor was actively involved in the legislative process –, or not (0). Governors can play a pivotal role in the legislative process by both setting an issue on the legislative agenda and influencing the policy outcome (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson, Gray, Hanson and Kousser2017: 256–257). On the one hand, they can include same-sex marriage among their legislative priorities, draft a marriage equality bill, and find sponsor legislators, who will introduce it to the state legislature. On the other hand, governors can advocate the bill to lawmakers and negotiate majority support in the state legislature for its adoption. In doing so, they can also limit the scope of the political conflict and push legislators to reach a ‘reasonable’ solution to the problem (Sabatier, Reference Sabatier1988: 141), for example, by proposing bills that afford generous religious exemptions.

Exemptions afforded to religious officials and organizations by the marriage equality bill (EXEMP)

This condition is dichotomous, with 0 meaning that none or only First Amendment religious exemption clauses were included in the marriage equality bill and 1 indicating that the clergy at the very least is protected from private lawsuits and government penalty.

Existence of veto possibilities (VETO)

This dichotomous condition measures whether the political context offers defenders of the status quo veto possibilities. It is hence coded as 1 if the institutional veto players are not likely to agree to institutional change – that is, when Republicans control both the executive and the legislative, or if the government is divided.Footnote 7 It also takes the value of 1 if there is the possibility of a popularly initiated legislative referendum that might repeal the newly enacted legislation.

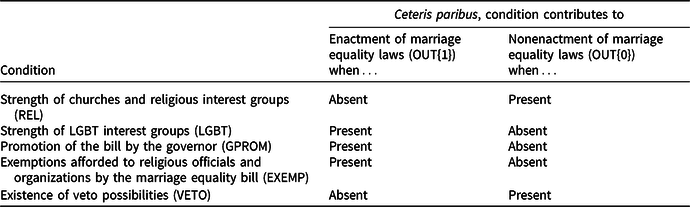

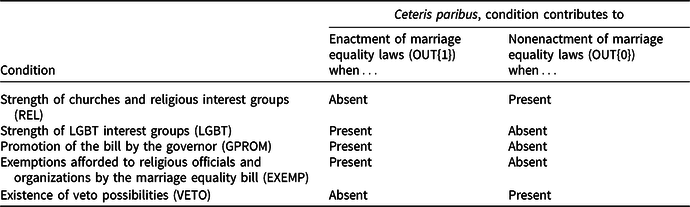

By applying the Enhanced Standard Analysis (software: R packages QCA and SetMethods; Duşa et al. Reference Duşa2019; Oana et al. Reference Oana, Medzihorsky, Quaranta and Schneider2018) and specifying the theoretically informed directional expectation shown in Table 1, I derive an intermediate solution that incorporates only easy and simplifying counterfactuals and avoids implausible and untenable assumptions about the outcome and its negation (Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 200–211).Footnote 8

Table 1. Conditions and directional expectations

Results

Starting with the analysis of necessity and using the highest level of consistency (1), the results reveal that the inclusion of religious exemption clauses is the only singularly necessary condition for the legislation in favor of marriage equality to be adopted.Footnote 9 Indeed, these clauses allow the bill to resonate with conservative constituencies and elites, thus garnering public support and facilitating the acceptance of the new institution.

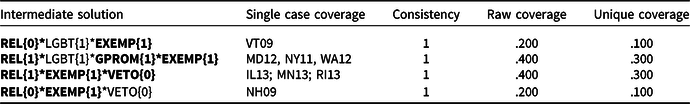

Continuing with the analysis of sufficiency, Table 2 shows the four paths that lead to the adoption of legislation in favor of same-sex marriage and displays the typical cases for each path, that is, those cases that are uniquely covered by each term of the solution. The intermediate solution indicates that by persuading institutional veto players – that is, legislators and/or governors – that the adoption of the new institution was necessary, change actors put marriage equality on the legislative agenda. The displacement of heterosexual marriage was successful, first, in those states where LGBT advocates were more powerful than defenders of the status quo in terms of lobbying resources and political alliances. This is the case of those states encompassed by the first and second terms of the solution, namely, Vermont in 2009, as well as New York in 2011 and Maryland and Washington in 2012. Both Vermont and New York featured a divided government, with a Republican governor and a Republican senate, respectively. In Vermont, LGBT interest groups’ mobilization successfully pushed lawmakers to enact the first marriage equality law in the nation. Republican governor Douglas vetoed the bill, but religious conservatives did not have enough resources to effectively lobby legislators. Moreover, the inclusion of religious exemption clauses further weakened opposition among elected officials and helped assembling the supermajority that overrode the governor’s veto (Wilson and Kreis, Reference Wilson and Kreis2013: 504). In New York, LGBT advocates countered the strong position of the Catholic Church by forging an alliance with Governor Cuomo. Cuomo played a crucial role in the policy-making process both by putting same-sex marriage on the legislative agenda and by advocating for the new institution. The bill was successfully adopted after the governor negotiated a majority coalition with conservative legislators by including more generous religious exemptions (Wilson and Kreis, Reference Wilson and Kreis2013: 496–498). In Maryland and Washington, Democrats controlled the government, but the institutional setting allowed for direct democracy initiatives, through which the law could be repealed. Status quo actors gathered enough signatures to place the legislation on the ballot and fiercely campaigned against marriage equality (Solomon, Reference Solomon2014: 237). With a view to overcoming these obstacles (i) the bill needed to be appealing to legislators, who were facing the electoral threat of a referendum (i.e. to include generous religious exemption clauses) and (ii) LGBT interest groups had to invest many resources in campaigns to win over not only lawmakers but also constituents at the ballot (Wilson and Kreis, Reference Wilson and Kreis2013: 507; Solomon, Reference Solomon2014: 248). As in New York, persuading the governor that the adoption of the new institution was necessary, allowed change actors to both put marriage equality on the legislative agenda and to sustain defection from the old institution. Governor O’Malley of Maryland and Governor Gregoire of Washington modeled their bills after New York’s watershed legislation and actively promoted them together with their staff and LGBT advocates (National Public Radio, 2012; Tavernise, Reference Tavernise2012).

Table 2. Sufficient conditions for the enactment of marriage equality laws

Letters in bold indicate the parsimonious solution. Solution consistency: 1; Solution coverage: 1.

Second, marriage equality laws were enacted in those states where the balance of power in favor of Democrats and the absence of institutional veto points offered status quo actors no possibilities of boycotting the legislative process. This is the case of New Hampshire in 2009 as well as Illinois, Minnesota, and Rhode Island in 2013, comprised by the third and fourth paths of the solution. While Democratic control of the government increased the congruence between institutional veto players, the proposed bills offered wide exemptions for religious officials and organizations, thus further lowering possible resistance to the recognition of same-sex marriage among lawmakers. The main difference between these terms lies in the power of religious conservatives and the ways in which LGBT advocates ensured the defection to the new institution. While in New Hampshire, churches and religious interest groups were weak in Illinois, Minnesota, and Rhode Island, they had considerably more power. In heavily Catholic Rhode Island, change actors had to overcome the opposition by Catholic legislators within the Democratic ranks, which blurred the lines of inter-party polarization on this issue (Bidgood, Reference Bidgood2013). In Minnesota, the Religious Right mobilized a considerable amount of resources in favor of a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage proposed in 2012, which was nevertheless clamorously defeated. The defeat afforded, in turn, a wave of popularity to the 2013 bill (Mannix, Reference Mannix2013). Lastly, Illinois featured powerful status quo actors – mainly the Catholic and Black Protestant churches – but not particularly strong LGBT interest groups. In this case, the successful defection to the new institution might have been enabled by the US Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Windsor (2013). The ruling, which holds that restricting the federal interpretation of marriage only to opposite-sex couples was unconstitutional, represented a major victory of LGBT advocates’ federal strategy (Wilson, Reference Wilson2014: 1167).

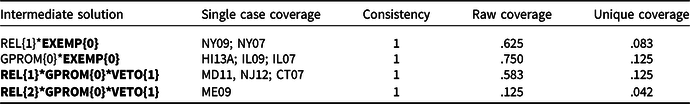

Table 3 presents the four paths that led to the passage of the proposed marriage equality bills to fail. The intermediate solution reveals two main ways through which status quo actors delayed or put an end to the legislative process. First, religious exemption clauses are a fine example of how defenders of the status quo can employ the religious values associated with the institution of marriage to counter reform (Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016). Given that religious liberties are constitutionally protected by the First Amendment, status quo actors instrumentalized the absence of religious exemptions to stoke up fears that marriage equality would force religious officials and organizations to act against their conscience and moral convictions (Wilson and Kreis, Reference Wilson and Kreis2013). In fact, the results of the Enhanced Standard Analysis show that the absence of religious exemption clauses is the only singularly sufficient condition for same-sex marriage bills to fail. This is the case of those states covered by the first and second terms of the solution. Similar to the political situation in 2011, New York in 2007 featured a divided government with a Republican senate. Governor Spitzer put the issue of marriage equality on the legislative agenda, but the bill did not offer religious exemption clauses generous enough to circumvent the Catholic Church’s strong opposition and to garner support from conservative lawmakers. The same happened in 2009, despite the Democrats’ control of the government (Wilson and Kreis, Reference Wilson and Kreis2013: 496). Both in Hawaii in 2013 and Illinois in 2007 and 2009, no political or institutional veto points were in place, but status quo actors managed to delay institutional change because the proposed bills did not afford any exemptions to religious officials and organizations (Wilson and Kreis, Reference Wilson and Kreis2013: 495). Moreover, LGBT interest groups were not particularly powerful, especially compared to the Catholic and Black Protestant churches in Illinois. They also did not form alliances with the governors to promote the bills and push for the defection to the new institution. This combination of factors gave Democratic lawmakers in these states little incentives to favor bills that could possibly trigger an electoral backlash at the polls.

Table 3. Sufficient conditions for the nonenactment of marriage equality laws

Letters in bold indicate the parsimonious solution. Solution consistency: 1; Solution coverage: 1.

Second, marriage equality bills failed when the political balance of power and institutional veto points offered status quo actors opportunities to either delay or stop the adoption of marriage equality laws. The third and fourth paths of the solution include those states in which status quo actors managed to forge coalitions with key institutional veto players – that is, legislators and/or governors – that would take the issue off the legislative agenda. As well, they comprise those states in which opponents of marriage equality succeeded in countering displacement by making use (or credibly threating to make use) of the institutional veto points offered by popularly initiated referendums. In heavily Catholic Connecticut in 2007, lawmakers did not feel confident enough to pursue a bill that Republican governor Rell threatened to veto, regardless of the exemptions provided to religious officials and organizations (Altimari, Reference Altimari2007). In New Jersey, in 2012, Republican governor Christie’s ability to enforce party discipline triumphed over marriage equality advocates’ efforts, who did not manage to gather enough Republican votes to override the governor’s veto (Solomon, Reference Solomon2014: 334). Thus, status quo actors’ coalition with Republican governors and legislators made it easier for opponents of marriage equality to enter the policy-making process and effectively stop legislative efforts to pursue marriage equality in both states. Conversely, in Maryland in 2011, as well as in Maine in 2009, the government was controlled by Democrats, but churches and religious interest groups threatened to repeal the laws through popularly initiated legislative referendums. Indeed, in Maine, the newly enacted marriage equality law did not survive a veto referendum. The loss might have been due to the fact that the bill’s religious exemptions did not cover religious organizations (Wilson and Kreis, Reference Wilson and Kreis2013: 507–508), as well as to the opponents’ more effective campaign, which exceeded its voter turnout target (Wolfson, Reference Wolfson2017: 228). Either way, losing at the ballot box effectively discouraged lawmakers from taking further legislative action in favor of marriage equality. Finally, in Maryland, status quo actors succeeded in convincing conservative Democratic legislators, who faced the electoral threat of a referendum, to withdraw their support to the bill (Tavernise, Reference Tavernise2011). In this case, they were only effective in delaying institutional change until the legislative session of 2012.

Discussion

This research has sought to provide new theoretical and empirical insights into the adoption of marriage equality legislation in the American states and to offer a new perspective on an issue mainly studied in the field of morality policies. The employed institutionalist approach offers a powerful tool to study the politics of marriage equality as it places the analytical focus on the dynamic relationship between proponents and opponents of change, as well as between actors and the political context in which they operate (Erikson, Reference Erikson2017; Smith Reference Smith, Winter, Forest and Sénac2018). Classical morality policy studies (e.g. Lax and Phillips, Reference Lax and Phillips2009; Mooney, Reference Mooney2000; Mooney and Lee, Reference Mooney and Lee2000) have highlighted the importance of public opinion for explaining cross-state variation in policy outputs. Accordingly, not only do morality policy outputs respond to a state’s public opinion, but a divided constituency also makes the policy intractable – that is, the value clash within the constituency increases the electoral costs for policymakers of taking a decision that might alienate part of the electorate. Value contention among constituents will therefore result in policy deadlock (Engeli and Varone, Reference Engeli and Varone2011). Yet, the empirical findings show that, while a positive public opinion enables change actors to propose the new institution of marriage equality, the successful displacement of heterosexual marriage is crucially shaped by actors’ strategies, as well as by the reform and veto opportunities that the political setting affords. These factors permit understanding why marriage equality bills failed to pass in states and years in which public opinion towards same-sex marriage was very favorable, such as New Jersey in 2012 or New York in 2009. At the same time, by showing that the inclusion of religious exemption clauses is an essential condition contributing to the success or failure of marriage equality laws, the results challenge the classic notion that value-loaded issues such as marriage equality are not amenable to negotiation and compromise (Meier, Reference Meier1999: 686). Even though consensus on first principles remains unlikely, the inclusion of religious exemption clauses is an example of pragmatic compromise on ‘secondary aspects’ of the policy – that is, instrumental considerations on how the policy ought to be implemented (Sabatier, Reference Sabatier1988: 144–145). Such a compromise results from the ongoing conflict during the process of institutional design that forces change actors to make concessions in order to forge a large enough coalition for the new institution to be adopted. Hence, the inclusion of religious exemptions increases the tractability of marriage equality, allowing LGBT advocates and their political allies to avoid deadlock even in a setting of a fundamental clash of values within the constituency. While the decision of eliminating the gender specificity of the right to marry alters the values on which the institution of marriage is based, religious exemption clauses represent a ‘live and let live’ solution (Engeli and Varone, Reference Engeli and Varone2011: 248) that makes the alteration of the status quo less electorally risky for policymakers.

An actor-centered approach that gives the same analytical consideration to both change and status quo actors also allows expanding our understanding of processes of gradual institutional change (Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg, Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2013: 287). The empirical results lend support to the notion of gradual displacement as a ‘costly’ strategy to bring about gender reform, as change actors need both the opportunity and sufficient power to initiate and sustain the defection from the old institution (Waylen, Reference Waylen2014: 218). Thus, even when Democratic-controlled governments allow LGBT advocates to place marriage equality on the legislative agenda, more efforts are needed to change the status quo than to preserve it. Indeed, to achieve displacement change actors need not only to be more powerful in terms of financial resources, mobilization potential, and alliances with key veto players than their opponents but also to be willing to compromise and accept religious exemption clauses. This compromise may weaken the new policy, as it allows status quo actors to water down policy proponents’ preferred institutional arrangements and thereby foster an ineffective compliance and debilitate its future implementation (Verge and Lombardo, Reference Verge and Lombardo2019: 4).

Moreover, the findings highlight how the gradual nature of institutional displacement offers opportunities for political learning to change and status quo actors alike (Mandelkern and Koreh, Reference Mandelkern and Koreh2018). Political learning might either entail policymakers adjusting the content of their policy proposals so as not to suffer electoral losses or policy advocates learning about how to best promote their preferred policies (Vagionaki and Trein, Reference Vagionaki and Trein2019: 7–8). While marriage equality was initially adopted only in those states in which conservative religious interest groups and churches were weak, namely, Vermont and New Hampshire in 2009, political learning allowed change actors and their allies to subsequently achieve displacement in states in which institutional hurdles in the form of popularly initiated legislative referendums or divided governments offered powerful opponents opportunities to block change, such as New York in 2011 and Washington in 2012. At the same time, status quo actors learned how to take advantage of the religious values associated with the institution of marriage to counter pressures for reform and force change actors to accept compromise on religious exemption clauses.

While I improve upon the existing literature’s measurements of interest groups’ strength (e.g. Beer and Cruz-Aceves, Reference Beer and Cruz-Aceves2018; Haider-Markel, Reference Haider-Markel2010) by taking into account their political contributions instead of only focusing on the shares of religious and LGBT constituencies as their mobilization potential, my measures remain proxies to interest groups’ strength. More data and research are needed to further delve into the ways these actors advocate for their preferred policy outputs. For instance, updated data on Religious Right organizations’ strength in state Republican parties (see Conger, Reference Conger2010), as well as new data on LGBT interest groups’ strength in state Democratic parties, would provide researches with additional valuable information on their power to influence the legislative process. As well, a deeper analysis of the negotiation process between LGBT interest groups, religious organizations, and lawmakers is needed to better document and analyze the process that leads to compromise and therefore explain why states adopted different types of religious exemptions.

Lastly, regarding the findings’ scope, I expect similar mechanisms to be at work in the United States for other so-called ‘manifest’ morality policies (Knill, Reference Knill2013: 312), such as abortion or euthanasia, where value conflicts underlie political decision making. Furthermore, despite the ‘exceptionalism’ of the US context (Studlar and Burns, Reference Studlar and Burns2015: 287), comparative lessons regarding the importance of actors’ resource mobilization and political alliances, as well as policy compromises, could be drawn for other countries. Specifically, those countries displaying multiple governance sites and belonging to what Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen (Reference Engeli, Green-Pedersen, Larsen, Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen2012: 15–19) define as the ‘religious world’, where the divide between secular and religious positions provides fertile ground for political mobilization by issue groups and becomes a characteristic element of the party system, as well as of political controversy within civil society.

Conclusion

This study builds on and contributes to the institutionalist literature by operationalizing and empirically analyzing gradual displacement, a mode of institutional change that has so far received limited attention (Van der Heijden, Reference Van der Heijden2010: 234). It considers cases in which legislative attempts to institutionalize marriage equality have been hindered, thereby also answering recent scholarly calls to conceptualize defenders of the status quo not just as veto points, but as actors that actively seek to preserve institutional stability (Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016: 23; Van der Heijden and Kuhlmann, Reference Van der Heijden and Kuhlmann2017: 550). By employing a methodological approach that allows for complex causation, the empirical analysis pinpoints the multiple chains of conditions that result either in failed or in successful attempts at institutional change. The findings indicate that while the political setting creates opportunities and constraints, it does not mechanistically determine whether displacement will ultimately occur. Rather, institutional reform is crucially shaped by both change and status quo actors’ resources and strategies.

This research also contributes to the morality policy scholarship by showing that negotiation and compromise on value-loaded issues are possible. Resistance by defenders of the status quo during the process of institutional design forces change actors to revise their preferred instruments and accept the inclusion of religious exemption clauses. Indeed, the inclusion of these clauses is a necessary condition for marriage equality laws to pass and their absence is a sufficient condition for the bills to fail.

Finally, in recent years, exemptions for both private and public actors on religious freedom grounds have proliferated not only with regard to marriage equality but also other morality policies. While states such as Michigan and South Dakota have enacted laws allowing state-licensed adoption agencies to refuse to place children with LGBT married couples, the US Supreme Court decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014) determined that certain corporations are entitled to exemptions to the contraceptive mandate of the 2010 Affordable Care Act if it violates their religious belief. These developments open up new avenues for future research on how compromise may offer opportunities for defenders of the (old) status quo to revert liberalizing reform.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000090.

Acknowledgements

A heartily thank you goes to Tània Verge, who keeps mentoring me even from far away. I am also very grateful to Josefina Erikson, who provided key inputs to my understanding of the issues at hand, as well as to Pär Zetterberg, for his valuable feedback. I thank my colleagues who contributed with their time, knowledge, and constructive criticism to this article: Christoph Hedtrich and Francesco Pasetti. Finally, I also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.